#Euthycarcinoids

Text

Incidents and Reflections Episode 67 - 06/21/2020

youtube

For anyone who missed or wants to re-experience the Dino Nerds for Black Lives stream back in June, you can now watch a recorded version of our one-time revival, as well as almost 40 hours’ worth of other paleo presentations!

Article links

Prehistoric Road Trip [02:26]

Ensonglopedia of the Human (recorded stream of WIP performance) [05:13]

Life Through the Ages II [08:31]

PhyloCode, Phylonyms, and RegNum [11:33]

Ontogenetic dietary shifts in Deinonychus [18:21]

Thermal comfort of Triassic dinosaurs [27:51]

Aquatic stem myriapods [36:27]

Peopling of the Caribbean [44:22]

#Palaeoblr#Paleontology#Dino Nerds for Black Lives#Podcast#Science#Dinosaurs#Deinonychus#Metabolism#Physiology#Euthycarcinoids#Myriapods#Arthropods#Evolution#Anthropology#Humans#Prehistoric Road Trip#Ensonglopedia#PhyloCode#Nomenclature#Incidents and Reflections

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Euthycarcinoids were a group of arthropods that lived between the mid-Cambrian and the mid-Triassic – but despite existing for over 250 million years their fossil record is incredibly sparse, and it's only within the last decade that they've been recognized as being close relatives of modern centipedes and millipedes.

The earliest members of this group were marine, living in shallow tidal waters, but they quickly specialized into brackish and freshwater habitats and were even some of the very first animals to walk on land. Fossil trackways show they were amphibious, venturing out onto mudflats to feed on microbial mats, avoid aquatic predators, and possibly lay their eggs in a similar manner to modern horseshoe crabs.

Most euthycarcinoid species are known from tropical and subtropical climates, but Antarcticarcinus pagoda here hints that these arthropods were much more widespread and diverse than previously thought. Discovered in fossil deposits in the Central Transantarctic Mountains of Antarctica, it lived in freshwater lakes during the Early Permian (~299-293 million years ago), at a time when the region was in similar polar latitudes to today with a cold icy subarctic climate.

About 8.5cm long (3.3"), it would have had a similar three-part body plan to other euthycarcinoids – with a head, a limb-bearing thorax, and a limbless abdomen ending in a tail spine – but its most distinctive feature was a pair of large wing-shaped projections on the sides of its carapace. These may have helped to stabilize its body when resting on soft muddy surfaces, spreading out its weight, or they might even have functioned as a hydrofoil generating lift while swimming.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#antarcticarcinus#euthycarcinoidea#mandibulata#arthropod#invertebrate#art

291 notes

·

View notes

Photo

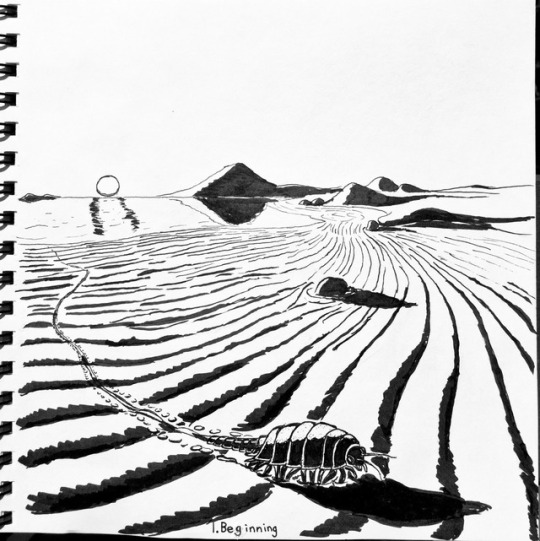

October 1st, “Beginning”

First day of Inktober! In keeping with the theme of beginnings, I decided to go back--way back--to the Late Cambrian period. On a tidal flat somewhere in what will one day be North America, a euthycarcinoid--an ancient arthropod that may represent the common ancestor of crustaceans, myriapods, and hexapods--crawls along the exposed mud in search of bacterial films to graze on. In its wake it leaves behind a distinctive track, fossils of which will one day bear the name Protichnites. This creature’s brief forays out of the water mark the beginning of life on land. Everything that came after--plants, insects, mollusks, tetrapods--followed in its footsteps.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life on a Moving Skyscraper, Crossing the Great Lakes

The room was moving when I woke. The propeller’s rotation shook the toilet, chipboard closets, desk, bed, couch, doors. Lakers are less rigid than oceangoing freighters because they don’t have to withstand the same conditions. The 740-foot Algoma Equinox was built on the Yangtze River in China. Builders welded additional steel supports into it so that the ship wouldn’t break in half during the journey back to the Great Lakes. The supports have since been removed, Captain Ross said. You can see the hull bend when the Equinox hits a big wave.

Living on a moving skyscraper is a strange feeling. I had no idea where we were or what time it was most of the day. The ship’s interior is lit with fluorescent light and smells a bit like a hospital. The crew wanders in and out of the mess hall all day and usually eats silently.

Some of the men I sat next to I never saw again. The cook, Mike Newell, was a constant presence in the mess hall. He would come out while I was eating and talk for an hour or more. One day he told me a story about another writer who had ridden on the ship. Mike had spoken with him extensively as well, but the reporter hadn’t mentioned him in the piece he later published. “What is that?” he asked me. I said I didn’t know. “I’d like to find that guy,” he said, swatting the towel. “I’d like to show him a few things.” We stared at each other for a moment, then he walked back into the kitchen. He didn’t talk to me for two days after that.

The sky looked hazy blue from the wheelhouse, which stands 75 feet above the deck. A thick band of clouds blocked the sun. Mustard-yellow exhaust fell from the smokestack and hovered a few feet above the water. The deck was painted rust red, with white handles on cargo covers and bright-yellow safety instructions. Trees glided by at ten miles an hour. The ship crossed the border into Ontario last night, Captain Ross said. We were passing Cornwall Island when I walked into the wheelhouse. The border enters the Saint Lawrence River there and zigzags 200 miles to Lake Ontario.

The helmsman steered while Captain Ross told me stories about shipping on the lakes. He rarely looked away from the windshield when he spoke. If he needed to give a command, he spoke over whoever was talking. If an important announcement sounded on the radio, he tuned everything out and listened. When Tony called from the cruise room to say that the internet was down, Captain Ross hung up on him and gave another order: “Line up the buoys to starboard. Two degrees port. No. Two more.”

*

Captain Ross had spent the last 33 years on freighters. He was 60 years old, with receding sandy-brown hair and a graying goatee. He squinted constantly. Crow’s feet reached to his sideburns, and his stocky build easily filled his T-shirt. In Algoma company photos, he dons a navy-blue reefer jacket and a captain’s hat. In the wheelhouse, he wore jeans, a polo shirt, and sandals.

Ross was 27 years old when his father, a lifetime Great Lakes captain, called him from Quebec City and asked if he wanted to be a deckhand. It was December 2nd and he was working as a data entry clerk for the Hudson’s Bay Company—the same company that was formed by a royal charter in 1670 and that now operates a chain of department stores with Lord & Taylor and Saks Fifth Avenue. He was married and had a newborn son. His father said the money was good, so Ross packed his things and moved onto the 600-foot George M. Carl.

He watched his father break up a knife fight his first day on the canaller and spent the next two weeks scraping and painting the bridge, cleaning and prepping cargo holds, and tending mooring cables. Captain Ross’s father had been at sea for half of his childhood, and Ross had never considered being a sailor. After he got his check for two weeks’ work—$700—he told his wife he was joining the fleet full-time.

It took Ross just four years to work his way up from deckhand to wheelsman to mate to captain. He attended marine school winter sessions, when the seaway is closed, then logged required ship hours during the warm months. In 1986 he captained his first boat, John A. France, out of port. “The first time you’re out there on your own, you realize there is nobody else to ask what to do,” he said. “My second and first mate were 60 and I was 30, and they were calling me ‘Old Man.’”

The first trip went without incident. The next 30 freighters he captained were not as easy. Gangs operated on the ships, and many of the deckhands were ex-cons who couldn’t get work elsewhere. The industry needed men so badly that if Captain Ross fired someone one day, he saw him on a competitor’s ship the next. Ross watched men get crushed by machines, mooring cables, and cargo hatches. He went looking for mates when they were late for a shift, only to find out that they had thrown themselves off the stern in the middle of the night.

“The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Paradise, Michigan, estimates that 6,000 ships and 30,000 lives have been lost on the lakes.”

Regulations were looser back then. The crew made swimming pools by spreading tarps between cargo hatches during lake crossings and drank beer poolside all afternoon. They gambled and partied deep into the night and, sometimes, while waiting to get into a lock, they jumped overboard to cool off. “All we had was one TV in the cruise room,” he said. “Going past Cleveland we could see an hour of a baseball game until we lost reception. Everyone congregated then; no one stayed in their cabin. We’d have 30 people in the galley playing cribbage, guitar, and cards. It made for a tighter-knit crew.”

*

The 300-square-mile Great Lakes basin spans about a quarter of America’s northland. The coastlines of all five lakes combined add up to just under 11,000 miles, almost half the distance around the world. An average of 200,000 cubic feet of precipitation falls somewhere on the lakes every second.

Water and latitude determine what lives or dies in the basin. In the north, the central Canadian Shield forest of fir, spruce, pine, quaking aspen, and paper birch is so dense that you can barely walk through it. Ridges and spires of gneiss and granite rise above the canopy.

Move south and east, and sugar maple, yellow birch, white pine, and beech take over the land. All the way south, near the mouth of Lake Ontario, the Great Lakes–Saint Lawrence forest is mostly red maple and oak, with elm, cottonwood, and eastern white cedar at lower elevations.

You think about these things when you have nothing to do but stare for hours at an unimaginable mass of water. You think about the natural border that the lakes and the Saint Lawrence create and how it helped shape political boundaries. You think about the seasons, the intricacy of biospheres, water cycles, heat cycles, the planet’s orbit, and its wobbly spin that makes night and day.

Two wood ducks swam away from the bow. The ship missed them by ten feet.

*

Thousands of mayflies swarmed the smokestack. They came from the water as nymphs, rose to the surface, grew wings, and flew. They are ancient insects. Aristotle wrote about their incredibly brief life span. There are other prehistoric creatures around here. The oldest known footprints on the planet were discovered in a Kingston, Ontario, sandstone quarry a hundred miles upstream. Scientists say they were made by foot-long insects called euthycarcinoids 500 million years ago. They were among the first creatures to migrate from water to land. Before the discovery, the quarry owner used the fossils as lawn ornaments.

Isolation and boredom aren’t the only danger on the lakes, Ross said. He pointed to a chart on the wall and showed me locations of a few shipwrecks. Superior and Michigan are the most dangerous because they are the longest—giving storms enough fetch to create two-story waves. Fronts flowing west to east in the fall are particularly rough. The lakes sit in a lowland between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachians. Cold, dry air flows down from the north and meets warm, moist air coming up from the south. Add prevailing westerlies rolling off the Rockies and you get a vortex of constant and dangerously unstable weather. Winds can blow 40 to 50 miles an hour and whip up waves 25 feet tall, Captain Ross said.

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Paradise, Michigan, estimates that 6,000 ships and 30,000 lives have been lost on the lakes. The gale of November 11, 1835, sank 11 ships on Lake Erie alone. The Mataafa Storm of 1905 sank or damaged 29 freighters, killed 36 seamen, and caused $3.5 million in damages. Storm losses in 1868 and 1869 led to the first national weather-forecasting system in the US, initially managed by the US Army Signal Corps using telegraphs in Great Lakes port cities. The most famous wreck, the Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank in a November gale in 1975 with all 29 crew, went down a few hundred miles ahead on our route.

A few miles upstream, the river widened to five miles across. We passed Chippewa Bay and entered Thousand Islands, New York—summer home to millionaires for a century and a half. There are 1,864 islands along the 50-mile stretch. Most have mansions or sleek, modern houses on them. Many were retreats for business moguls and movie stars in the Gilded Age.

Back then, a short train ride from New York City to Clayton, New York, left visitors a few steps from a ferry or private launch that would take them to their house or hotel.

I stepped onto the wheelhouse deck to see Singer Castle. Sixty-foot stone walls and terra-cotta roof tiles glowed in the late-afternoon light. The water around Dark Island, which the castle sits on, was deep azure. Frederick Gilbert Bourne of the Singer Sewing Machine Company built the fortress. It is a medieval revival structure with 28 rooms, armored knights guarding a marble fireplace, a walnut-paneled library, and secret passageways from which hosts can spy on their guests. A few miles farther, on Heart Island, was another castle, built by George Boldt, proprietor of New York City’s original Waldorf Astoria. Boldt built it for his wife and had hearts inlaid in the masonry. When she died (or ran off with the chauffeur—stories conflict), construction stopped.

“It was interesting to watch people gazing at the ship. I wasn’t sure what solace it would give onlookers to know that the three men driving it were wearing Crocs and sweatshirts and laughing hysterically about their in-laws.”

Every island has a story. Thousand Island salad dressing was born when actress May Irwin tried it on a fishing trip there. Irwin shared the recipe with Boldt, who added it to the menu at the Waldorf. On a nearby island, a cabin burned down in 1865. In the ashes, a man was found with his throat slit and a knife stuck in his chest. It was allegedly John Payne, a hit man hired by John Wilkes Booth to kill Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, William H. Seward. When Payne didn’t complete the job, and ran off with Booth’s money, Booth’s associates tracked him down.

A few houses on the North Shore looked like French châteaux with steep, peaked roofs and arched windows. Turreted homes and gingerbread-style cabins had replaced a 19th-century Methodist camp in Butternut Bay. Cattail marshes and lush reed beds edged the shoreline, and antique boats spanning a century circled the Equinox: split-cockpit runabouts, hard-chine sedan commuters, Nathanael Herreshoff steamers, sailboats, and Jet Skis.

The first mate pointed out an old steam-powered dory chugging toward shore as an SOS message was broadcast on the radio. A sailboat had lost power and was floating a few hundred yards dead ahead of the Equinox. Luckily, someone was close by to tow it home. I asked the mate how long it would take the Equinox to stop if something was in the way. “It doesn’t stop,” he said. “You should see this place at night. Or in the fog.”

Beneath the boathouses and million-dollar yachts, the Canadian Shield runs south across the Saint Lawrence and joins the Adirondacks. Twenty-five feet offshore, the water is 200 feet deep. Just behind the signal buoys, granite shoals are only two feet deep. Many of the islands here are perched on the edge of the seam. To be counted as part of the archipelago, an island has to have at least one square foot of land above water level year-round and support at least two living trees.

It was interesting to watch people gazing at the ship. I wasn’t sure what solace it would give onlookers to know that the three men driving it were wearing Crocs and sweatshirts and laughing hysterically about their in-laws. That is not to say the Equinox crew is not highly professional. They are. It’s just that enough time on the water makes people a little kooky.

We passed Wolfe Island and broke into a deep-blue plane. The shores fell away to port and starboard, and the Erie-Ontario lowlands on the southern shore of Lake Ontario appeared as a green streak. Behind us I could see the sweep of Tug Hill Plateau, which divides the Lake Ontario and Hudson River watersheds. Due west was flat calm—liquid silver etched by puffs of wind and three ducks skittering away from the Equinox’s wake.

It took ten minutes to walk from the wheelhouse to the bow of the ship. It felt more like a boat up there. Wake peeled away from the bow. The air smelled like pond water. The sun was a bonfire three fingers off the lake. An exact image of the sky stretched across the surface of the water, and the horizon arced with the curvature of the earth.

The first mate throttled up to 17 miles an hour, and the bow of the Equinox plowed forward. The hard part was over. Captain Ross went to bed, and Second Mate Charles Chouinard took the helm. The only sign of land was a smokestack miles away on the western shore. When Brûlé and Champlain first arrived, they would have seen only water. There is no reason they would have thought the lakes were not an ocean, until they tasted them. There was no reason they would have thought they could cross them either, or that there would be more lakes on the other side.

Some historians believe that Champlain and his truchement were not chasing a dream.

*

The elusive Northwest Passage they heard about from Indian tribes might have been a sixth Great Lake. Thousands of years ago, Lake Agassiz contained more water than all the other Great Lakes combined. It reached west and north of Lake Superior. When the ice dams holding it in place melted about 8,000 years ago, a cataclysmic flood raged through the Mississippi Valley, into Lake Superior and up the Mackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean. Scientists theorize that the magnitude of the flood was so great that it might have disrupted ocean currents, cooled the climate, helped spread agriculture west across Europe, and been the source of several flood narratives, like the one in the Bible.

Ancestors of western tribes lived around the shores of Agassiz before it drained, and they passed on stories of the flood through the generations. The Huron may well have drawn the lake on birchbark at Lachine Rapids, leading Champlain to assume it was still there. By the time Brûlé made it to Huron Country, there was nothing left of it. Today, the remains of Agassiz can be seen 400 miles northwest in Lake Winnipeg.

__________________________________

Good read found on the Lithub

0 notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #58: Hymenocarina

The pancrustaceans are a grouping of mandibulates that contains all of the crustaceans and hexapods (insects and their closest relatives) along with their various stem-relatives.

They're critical components of most ecosystems on the planet, and are major parts of the nutrient cycle. In aquatic environments the crustaceans dominate, with modern copepods and krill being some of the most abundant living animals and making up enormous amounts of biomass providing vital food sources for larger animals. On the land springtails and ants are especially numerous, and the air is full of flying insects, the only invertebrates to ever develop powered flight. Some groups of insects have also co-evolved complex mutualistic partnerships with flowering plants and fungi.

Hexapods and insects don't appear in the fossil record until the early Devonian, but they're estimated to have first diverged from the crustaceans* in the early Silurian (~440 million years ago), around the same time that vascular plants were colonizing the land.

(* Hexapods are crustaceans in the same sort of way that birds are dinosaurs. They originated from within one of the major crustacean lineages with their closest living relatives possibly being the enigmatic remipedes.)

But crustaceans and their pancrustacean ancestors go back much further into the Cambrian, and we'll be finishing off this month and this series with some of those early representatives.

———

Some of the earliest known pancrustaceans were the hymenocarines, a lineage of superficially shrimp-like mandibulates with a bivalved carapace covering their head and thorax. Although known only from the Cambrian, they were a diverse group during their existence and were some of the most abundant arthropods in some fossil sites.

Sometimes they're considered to be early or stem-mandibulates, branching off before the euthycarcinoids and the myriapod lineage, but generally they're placed as some of the earliest known pancrustaceans – and Ercaicunia multinodosa helps support that idea.

Known from the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago), Ercaicunia was about 1.1cm long (~0.4"). Micro-CT scanning of some of its tiny fossils has revealed much of its anatomy in high detail, showing features that identify it as one of the earliest known pancrustacean fossils – and the earliest that isn't microscopic.

It was either part of an early branch of the hymenocarines, or alternatively wasn't quite an actual hymenocarine itself, possibly being a very close relative or stem-member of their lineage.

It had a pair of large oval valves forming a carapace around the front of its body, with its long limbless abdomen and tail fan extending out the back. There were 16 pairs of biramous limbs on its thorax and several pairs of small spines on its back, and its head bore two pairs of antennae – one large pair in front and another much smaller pair hidden under its carapace – along with a pair of mandibles and maxilluae.

It also doesn't seem to have had any eyes, suggesting it had some sort of lifestyle where vision wasn't much use. Its mouthparts also indicate it was probably feeding on something that required manipulation and chewing up, but details of its diet and ecology are still poorly understood.

———

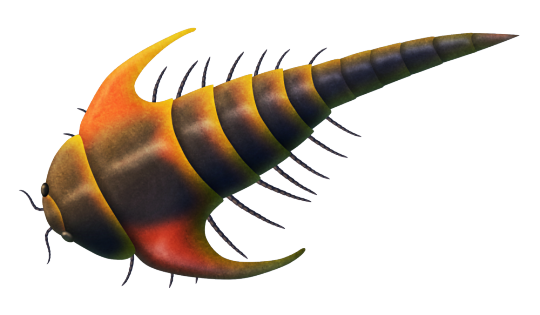

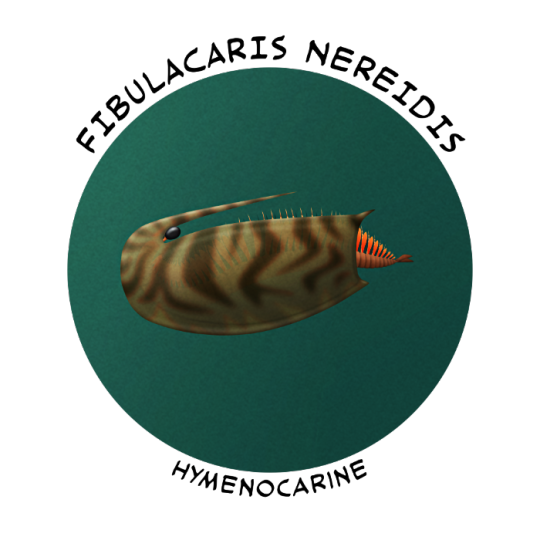

Fibulacaris nereidis was one of the more unusual hymenocarines, known from the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago).

Up to 2cm long (0.8"), its narrow keeled carapace had a long backwards-pointing spine, with the front of its body curling over completely in a U-bend so that its head also faced backwards. It had stalked eyes, no obvious antennae or mandibles, and around 40 pairs of limbs running all the way along to its tail fan, indicating it had either a very short or a non-existent abdominal region.

It was probably a filter-feeder, using the shape of its carapace and the beating of its many legs to create a current drawing plankton and suspended organic particles towards its mouth. The combination of this lifestyle and its unusual anatomy suggests it probably swam around upside down, similar to some modern crustaceans like fairy shrimp.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#ercaicunia#fibulacaris#hymenocarina#pancrustacea#mandibulata#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #56: Euthycarcinoidea

The euthycarcinoids were a group of euarthropods known from the mid-Cambrian to the mid-Triassic (~500-254 million years ago), surviving through multiple mass extinctions including the devastating "Great Dying" at the end of the Permian that finished off the trilobites. But despite an evolutionary history spanning around 250 million years they have a very sparse fossil record, extremely rare and known from less than 20 species across their entire time range.

For a long time their affinities were uncertain, and they've been variously suggested to have been crustaceans, trilobites, or chelicerates, or even to have been a lineage of earlier stem-euarthropods. But since the early 2010s better understanding of their anatomy has placed them in the mandibulates, probably as the closest relatives of the myriapods and helping to close the gap between the aquatic ancestors of that group and their earliest known terrestrial forms.

Most known euthycarcinoid species lived in brackish and freshwater environments, but some Cambrian species have been found in tidal flats associated with the terrestrial trace fossils Protichnites and Diplichnites – indicating that they were amphibious and some of the very first animals able to walk on land.

Mosineia macnaughtoni is a Cambrian euthycarcinoid known from the Blackberry Hill fossil deposits in Wisconsin, USA (~500-489 million years ago).

At around 10cm long (4") it was fairly large for a Cambrian euarthropod, and like other euthycarcinoids it had a three-part body plan with a head bearing antennae, eyes, and mandibles, a thorax with pairs of uniramous legs, and a limbless abdomen that ended in a tail spine.

It probably ventured out of the water to feed on the rich microbial mats that covered the mudflats, taking advantage of an environment free from predators and competition. It may also have laid and fertilized its eggs on the shore, similarly to modern horseshoe crabs.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#mosineia#euthycarcinoidea#mandibulata#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#just mosi-ing along

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life on a Moving Skyscraper, Crossing the Great Lakes

The room was moving when I woke. The propeller’s rotation shook the toilet, chipboard closets, desk, bed, couch, doors. Lakers are less rigid than oceangoing freighters because they don’t have to withstand the same conditions. The 740-foot Algoma Equinox was built on the Yangtze River in China. Builders welded additional steel supports into it so that the ship wouldn’t break in half during the journey back to the Great Lakes. The supports have since been removed, Captain Ross said. You can see the hull bend when the Equinox hits a big wave.

Living on a moving skyscraper is a strange feeling. I had no idea where we were or what time it was most of the day. The ship’s interior is lit with fluorescent light and smells a bit like a hospital. The crew wanders in and out of the mess hall all day and usually eats silently.

Some of the men I sat next to I never saw again. The cook, Mike Newell, was a constant presence in the mess hall. He would come out while I was eating and talk for an hour or more. One day he told me a story about another writer who had ridden on the ship. Mike had spoken with him extensively as well, but the reporter hadn’t mentioned him in the piece he later published. “What is that?” he asked me. I said I didn’t know. “I’d like to find that guy,” he said, swatting the towel. “I’d like to show him a few things.” We stared at each other for a moment, then he walked back into the kitchen. He didn’t talk to me for two days after that.

The sky looked hazy blue from the wheelhouse, which stands 75 feet above the deck. A thick band of clouds blocked the sun. Mustard-yellow exhaust fell from the smokestack and hovered a few feet above the water. The deck was painted rust red, with white handles on cargo covers and bright-yellow safety instructions. Trees glided by at ten miles an hour. The ship crossed the border into Ontario last night, Captain Ross said. We were passing Cornwall Island when I walked into the wheelhouse. The border enters the Saint Lawrence River there and zigzags 200 miles to Lake Ontario.

The helmsman steered while Captain Ross told me stories about shipping on the lakes. He rarely looked away from the windshield when he spoke. If he needed to give a command, he spoke over whoever was talking. If an important announcement sounded on the radio, he tuned everything out and listened. When Tony called from the cruise room to say that the internet was down, Captain Ross hung up on him and gave another order: “Line up the buoys to starboard. Two degrees port. No. Two more.”

*

Captain Ross had spent the last 33 years on freighters. He was 60 years old, with receding sandy-brown hair and a graying goatee. He squinted constantly. Crow’s feet reached to his sideburns, and his stocky build easily filled his T-shirt. In Algoma company photos, he dons a navy-blue reefer jacket and a captain’s hat. In the wheelhouse, he wore jeans, a polo shirt, and sandals.

Ross was 27 years old when his father, a lifetime Great Lakes captain, called him from Quebec City and asked if he wanted to be a deckhand. It was December 2nd and he was working as a data entry clerk for the Hudson’s Bay Company—the same company that was formed by a royal charter in 1670 and that now operates a chain of department stores with Lord & Taylor and Saks Fifth Avenue. He was married and had a newborn son. His father said the money was good, so Ross packed his things and moved onto the 600-foot George M. Carl.

He watched his father break up a knife fight his first day on the canaller and spent the next two weeks scraping and painting the bridge, cleaning and prepping cargo holds, and tending mooring cables. Captain Ross’s father had been at sea for half of his childhood, and Ross had never considered being a sailor. After he got his check for two weeks’ work—$700—he told his wife he was joining the fleet full-time.

It took Ross just four years to work his way up from deckhand to wheelsman to mate to captain. He attended marine school winter sessions, when the seaway is closed, then logged required ship hours during the warm months. In 1986 he captained his first boat, John A. France, out of port. “The first time you’re out there on your own, you realize there is nobody else to ask what to do,” he said. “My second and first mate were 60 and I was 30, and they were calling me ‘Old Man.’”

The first trip went without incident. The next 30 freighters he captained were not as easy. Gangs operated on the ships, and many of the deckhands were ex-cons who couldn’t get work elsewhere. The industry needed men so badly that if Captain Ross fired someone one day, he saw him on a competitor’s ship the next. Ross watched men get crushed by machines, mooring cables, and cargo hatches. He went looking for mates when they were late for a shift, only to find out that they had thrown themselves off the stern in the middle of the night.

“The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Paradise, Michigan, estimates that 6,000 ships and 30,000 lives have been lost on the lakes.”

Regulations were looser back then. The crew made swimming pools by spreading tarps between cargo hatches during lake crossings and drank beer poolside all afternoon. They gambled and partied deep into the night and, sometimes, while waiting to get into a lock, they jumped overboard to cool off. “All we had was one TV in the cruise room,” he said. “Going past Cleveland we could see an hour of a baseball game until we lost reception. Everyone congregated then; no one stayed in their cabin. We’d have 30 people in the galley playing cribbage, guitar, and cards. It made for a tighter-knit crew.”

*

The 300-square-mile Great Lakes basin spans about a quarter of America’s northland. The coastlines of all five lakes combined add up to just under 11,000 miles, almost half the distance around the world. An average of 200,000 cubic feet of precipitation falls somewhere on the lakes every second.

Water and latitude determine what lives or dies in the basin. In the north, the central Canadian Shield forest of fir, spruce, pine, quaking aspen, and paper birch is so dense that you can barely walk through it. Ridges and spires of gneiss and granite rise above the canopy.

Move south and east, and sugar maple, yellow birch, white pine, and beech take over the land. All the way south, near the mouth of Lake Ontario, the Great Lakes–Saint Lawrence forest is mostly red maple and oak, with elm, cottonwood, and eastern white cedar at lower elevations.

You think about these things when you have nothing to do but stare for hours at an unimaginable mass of water. You think about the natural border that the lakes and the Saint Lawrence create and how it helped shape political boundaries. You think about the seasons, the intricacy of biospheres, water cycles, heat cycles, the planet’s orbit, and its wobbly spin that makes night and day.

Two wood ducks swam away from the bow. The ship missed them by ten feet.

*

Thousands of mayflies swarmed the smokestack. They came from the water as nymphs, rose to the surface, grew wings, and flew. They are ancient insects. Aristotle wrote about their incredibly brief life span. There are other prehistoric creatures around here. The oldest known footprints on the planet were discovered in a Kingston, Ontario, sandstone quarry a hundred miles upstream. Scientists say they were made by foot-long insects called euthycarcinoids 500 million years ago. They were among the first creatures to migrate from water to land. Before the discovery, the quarry owner used the fossils as lawn ornaments.

Isolation and boredom aren’t the only danger on the lakes, Ross said. He pointed to a chart on the wall and showed me locations of a few shipwrecks. Superior and Michigan are the most dangerous because they are the longest—giving storms enough fetch to create two-story waves. Fronts flowing west to east in the fall are particularly rough. The lakes sit in a lowland between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachians. Cold, dry air flows down from the north and meets warm, moist air coming up from the south. Add prevailing westerlies rolling off the Rockies and you get a vortex of constant and dangerously unstable weather. Winds can blow 40 to 50 miles an hour and whip up waves 25 feet tall, Captain Ross said.

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Paradise, Michigan, estimates that 6,000 ships and 30,000 lives have been lost on the lakes. The gale of November 11, 1835, sank 11 ships on Lake Erie alone. The Mataafa Storm of 1905 sank or damaged 29 freighters, killed 36 seamen, and caused $3.5 million in damages. Storm losses in 1868 and 1869 led to the first national weather-forecasting system in the US, initially managed by the US Army Signal Corps using telegraphs in Great Lakes port cities. The most famous wreck, the Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank in a November gale in 1975 with all 29 crew, went down a few hundred miles ahead on our route.

A few miles upstream, the river widened to five miles across. We passed Chippewa Bay and entered Thousand Islands, New York—summer home to millionaires for a century and a half. There are 1,864 islands along the 50-mile stretch. Most have mansions or sleek, modern houses on them. Many were retreats for business moguls and movie stars in the Gilded Age.

Back then, a short train ride from New York City to Clayton, New York, left visitors a few steps from a ferry or private launch that would take them to their house or hotel.

I stepped onto the wheelhouse deck to see Singer Castle. Sixty-foot stone walls and terra-cotta roof tiles glowed in the late-afternoon light. The water around Dark Island, which the castle sits on, was deep azure. Frederick Gilbert Bourne of the Singer Sewing Machine Company built the fortress. It is a medieval revival structure with 28 rooms, armored knights guarding a marble fireplace, a walnut-paneled library, and secret passageways from which hosts can spy on their guests. A few miles farther, on Heart Island, was another castle, built by George Boldt, proprietor of New York City’s original Waldorf Astoria. Boldt built it for his wife and had hearts inlaid in the masonry. When she died (or ran off with the chauffeur—stories conflict), construction stopped.

“It was interesting to watch people gazing at the ship. I wasn’t sure what solace it would give onlookers to know that the three men driving it were wearing Crocs and sweatshirts and laughing hysterically about their in-laws.”

Every island has a story. Thousand Island salad dressing was born when actress May Irwin tried it on a fishing trip there. Irwin shared the recipe with Boldt, who added it to the menu at the Waldorf. On a nearby island, a cabin burned down in 1865. In the ashes, a man was found with his throat slit and a knife stuck in his chest. It was allegedly John Payne, a hit man hired by John Wilkes Booth to kill Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, William H. Seward. When Payne didn’t complete the job, and ran off with Booth’s money, Booth’s associates tracked him down.

A few houses on the North Shore looked like French châteaux with steep, peaked roofs and arched windows. Turreted homes and gingerbread-style cabins had replaced a 19th-century Methodist camp in Butternut Bay. Cattail marshes and lush reed beds edged the shoreline, and antique boats spanning a century circled the Equinox: split-cockpit runabouts, hard-chine sedan commuters, Nathanael Herreshoff steamers, sailboats, and Jet Skis.

The first mate pointed out an old steam-powered dory chugging toward shore as an SOS message was broadcast on the radio. A sailboat had lost power and was floating a few hundred yards dead ahead of the Equinox. Luckily, someone was close by to tow it home. I asked the mate how long it would take the Equinox to stop if something was in the way. “It doesn’t stop,” he said. “You should see this place at night. Or in the fog.”

Beneath the boathouses and million-dollar yachts, the Canadian Shield runs south across the Saint Lawrence and joins the Adirondacks. Twenty-five feet offshore, the water is 200 feet deep. Just behind the signal buoys, granite shoals are only two feet deep. Many of the islands here are perched on the edge of the seam. To be counted as part of the archipelago, an island has to have at least one square foot of land above water level year-round and support at least two living trees.

It was interesting to watch people gazing at the ship. I wasn’t sure what solace it would give onlookers to know that the three men driving it were wearing Crocs and sweatshirts and laughing hysterically about their in-laws. That is not to say the Equinox crew is not highly professional. They are. It’s just that enough time on the water makes people a little kooky.

We passed Wolfe Island and broke into a deep-blue plane. The shores fell away to port and starboard, and the Erie-Ontario lowlands on the southern shore of Lake Ontario appeared as a green streak. Behind us I could see the sweep of Tug Hill Plateau, which divides the Lake Ontario and Hudson River watersheds. Due west was flat calm—liquid silver etched by puffs of wind and three ducks skittering away from the Equinox’s wake.

It took ten minutes to walk from the wheelhouse to the bow of the ship. It felt more like a boat up there. Wake peeled away from the bow. The air smelled like pond water. The sun was a bonfire three fingers off the lake. An exact image of the sky stretched across the surface of the water, and the horizon arced with the curvature of the earth.

The first mate throttled up to 17 miles an hour, and the bow of the Equinox plowed forward. The hard part was over. Captain Ross went to bed, and Second Mate Charles Chouinard took the helm. The only sign of land was a smokestack miles away on the western shore. When Brûlé and Champlain first arrived, they would have seen only water. There is no reason they would have thought the lakes were not an ocean, until they tasted them. There was no reason they would have thought they could cross them either, or that there would be more lakes on the other side.

Some historians believe that Champlain and his truchement were not chasing a dream.

*

The elusive Northwest Passage they heard about from Indian tribes might have been a sixth Great Lake. Thousands of years ago, Lake Agassiz contained more water than all the other Great Lakes combined. It reached west and north of Lake Superior. When the ice dams holding it in place melted about 8,000 years ago, a cataclysmic flood raged through the Mississippi Valley, into Lake Superior and up the Mackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean. Scientists theorize that the magnitude of the flood was so great that it might have disrupted ocean currents, cooled the climate, helped spread agriculture west across Europe, and been the source of several flood narratives, like the one in the Bible.

Ancestors of western tribes lived around the shores of Agassiz before it drained, and they passed on stories of the flood through the generations. The Huron may well have drawn the lake on birchbark at Lachine Rapids, leading Champlain to assume it was still there. By the time Brûlé made it to Huron Country, there was nothing left of it. Today, the remains of Agassiz can be seen 400 miles northwest in Lake Winnipeg.

__________________________________

Good read found on the Lithub

0 notes