#D.H. Wulzen

Photo

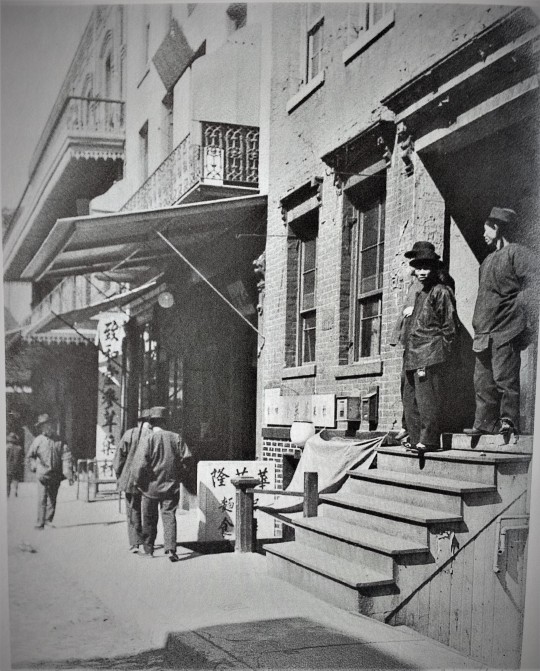

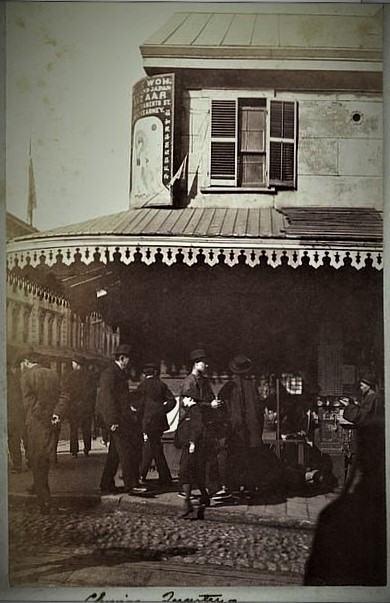

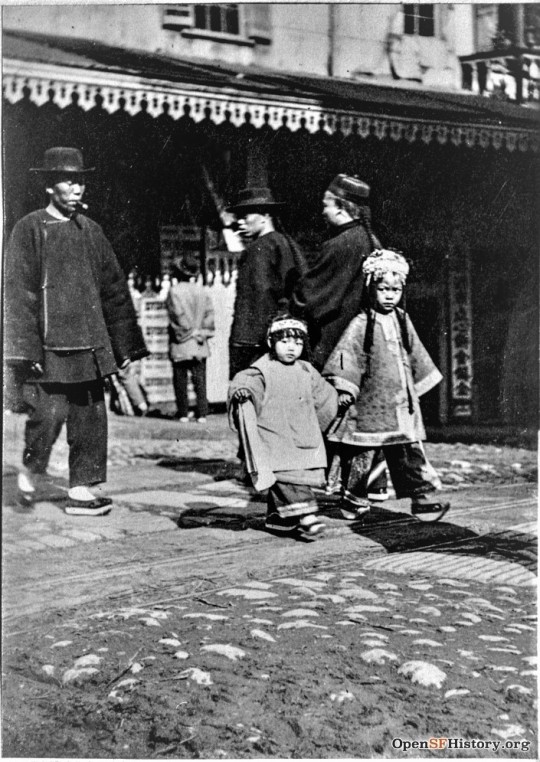

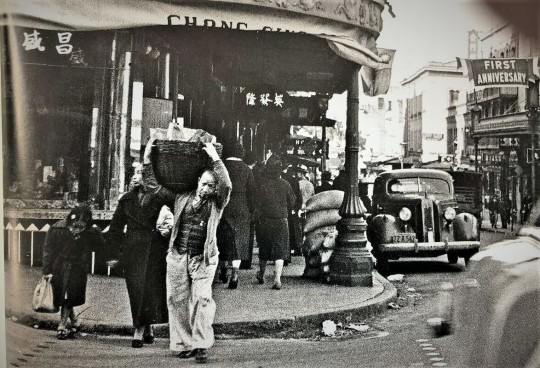

Untitled Chinatown street, c. 1898. (Photograph by Oscar Maurer (from the collection of the Oakland Museum of California, Museum Income Purchase Fund). The men seen in Maurer’s photo are standing on the landing of the stairs to 116 – 118 Waverly Place. Occupying a lot on the east side of the small street (and across from the Tin How temple and the headquarters and shrine of the Ning Yung district association), the building served as a boarding house.

Locating Oscar Mauer on Waverly Place (with a little help from D.H. Wulzen and the Goldsmith Bros.)

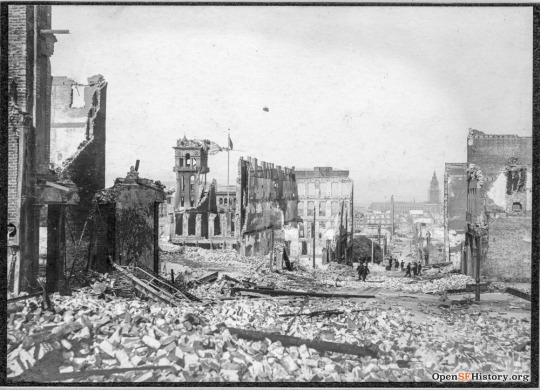

The Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906 obliterated San Francisco Chinatown so thoroughly that identifying the subject matter depicted by the scant photographic record of the community necessarily relies on chance and coincidence, and it often ends in futility. Not surprisingly, the untitled photo by Oscar Maurer taken in the late 1890s has eluded clarification by researchers of old Chinatown for decades.

Maurer migrated from his native New York City to study at the University of California at Berkeley and thereafter opened a photography studio in San Francisco. According to the Getty Museum, he became an associate member of Alfred Stieglitz's Photo-Secession and the first California-based photographer to achieve national prominence. “The only entrant from California in the first Chicago Camera Club Salon of 1900, Maurer received critical acclaim for his atmospheric landscape photograph The Storm. Encouraged by this success, he helped establish the first San Francisco Salon, held at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art in 1901. Maurer regularly contributed his Pictorialist landscape photographs to Camera Craft, the journal of the California Camera Club, and to Camera Work, Stieglitz's influential publication.

As was the case of most of his fellow photographers in San Francisco (such as his colleague and collaborator, Arnold Genthe), Maurer lost his studio and its contents in the earthquake and fire. Although he reopened his studio in Berkeley, where he remained for the rest of his life, his photographs of old Chinatown remain very rare.

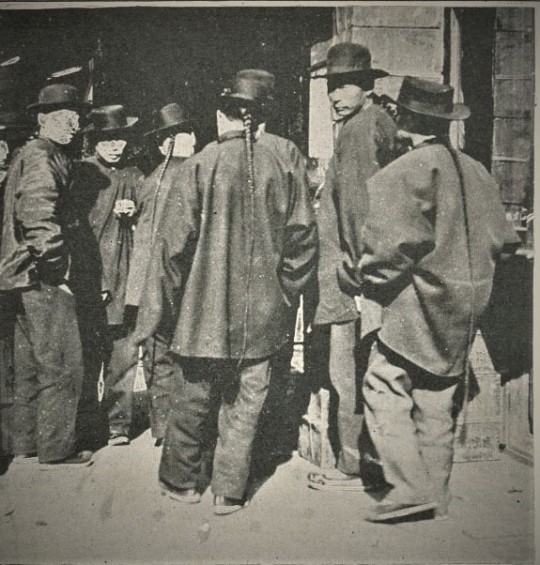

“Group of Highbinders Discussion a Late Proclamation, c. 1900. Photograph by Oscar Maurer (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

“San Francisco, 1906” Photograph by Oscar Maurer (from the collection of the Oakland Museum of California)

“San Francisco, 1906” Photograph by Oscar Maurer (courtesy of John Aronovici)

Fortunately for the researchers of old Chinatown, Maurer captured two crucial pieces of signage in his 1898 photograph that help in identifying the precise location in Chinatown of the buildings. The first example can be seen in the vertical sign appearing at the left of the frame, containing the characters 致和堂參茸藥材 (lit.: “Gee Wo Ginseng Medicinal Herbs;” canto: “gee wo tong sum yung yeuk choy;” pinyin: “Zhì hé táng cān rōng yàocái”). The Horn Hong & co. Chinese business directory and lunar calendar for 1892 shows the Gee Wo Tong company located at 124 Waverly Place.

Detail from the Horn Hong & Co. Chinese directory for 1892 for the Gee Wong Tong company.

By the publication of the 1895 Langley directory the Gee Tau Hong & Co. and Gee Wo Tong & Co. shared the premises at 124 Waverly Place. The 1905 Sanborn map for this Chinatown street confirmed the presence of, and use of the property by, the Chinese herbalists. Having established the street on which the herbalists operated, the location of the basement eatery whose entrance signage can be seen in the center can be located with equal precision.

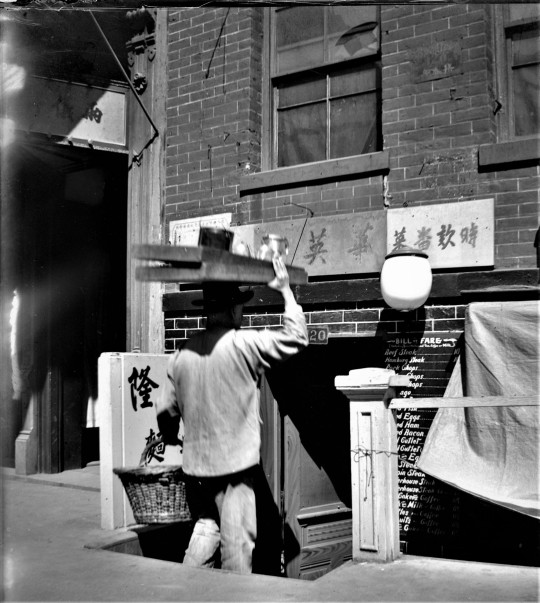

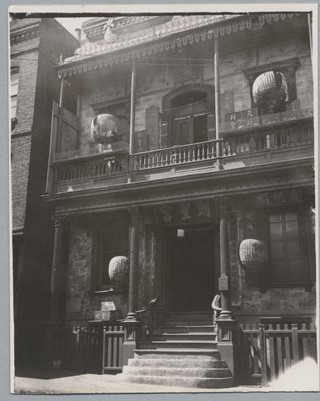

Moreover, by comparing Maurer’s photo with one by D.H. Wulzen of the same basement entrance, the full tradename of the eatery can be discerned as “Wah Ying Lung” 華英隆(canto: “wah ying loong”), a name which could also constitute literal shorthand for Chinese/English (or Chinese American). When viewed together, Mauer’s photo corroborates the partially-obscured address plate in the Wulzen photo as located at 120 Waverly Place.

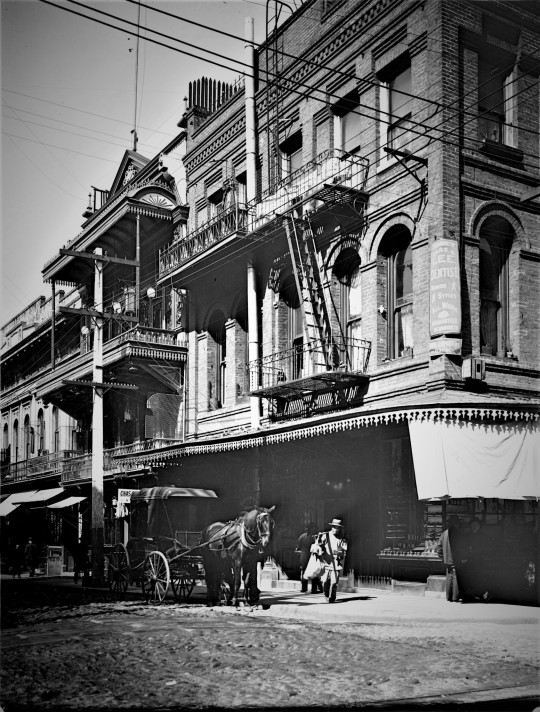

Restaurant worker returning from a delivery to a basement eatery, c. 1900. Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). The last two digits of the address at 120 Waverly Place can be seen over the door to the basement entrance. The right portion of the sign advertises literally seasonal, i.e., 時款 (canto: “see foon”) food.

Two boys play near the sign of the basement eatery “Wah Ying Lung” 華英隆(canto: “wah ying loong”), c. pre-1900. Photograph by the Goldsmith Bros. (from a private collection).

Having established the address of the Wah Ying basement eatery at 120 Waverly Place, the men seen in Maurer’s photo are standing on the landing of the stairs to 116 – 118 Waverly Place. Occupying a lot on the east side of the small street, and across from the Tin How temple and the headquarters and shrine of the Ning Yung district association, the building served as a boarding house. The 1905 Sanborn map confirmed its use as “lodgings.”

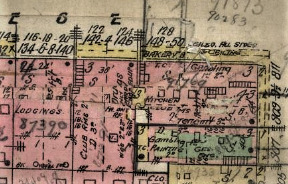

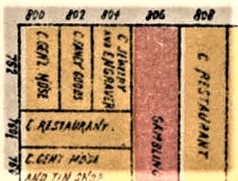

Detail showing Waverly Place in San Francisco Chinatown from the 1905 Sanborn Insurance Map (Vol. 1, Page 39-40) of San Francisco, prepared by the Sanborn-Perris Map Company, Limited, of New York.

A detail from “Waverly Place - April 9, 1900” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D. H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). This close-up looks north on Waverly Place from the intersection with Clay Street. Magnification of the center portion of the image shows the building elevation, the partial signage for the basement entrance to the Wah Ying eatery, and the stairs on which the trio of Chinese men stood for Oscar Maurer’s photo.

Thanks to the photographers of pre-1906 Chinatown such as Oscar Maurer, D.H. Wulzen, and the Goldsmith brothers, determined researchers can view the visual legacy of the Pictorialists and expand the public’s understanding of the gone world of old Chinatown.

[updated 2024-3-11]

#Oscar Maurer#Waverly Place#Gee Wo Tong & Co.#Wah Ying restaurant#D.H. Wulzen#Horn Hong & Co.#Goldsmith Bros.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scenes of Waverly Place: Then and Now

As the first quarter of the 21st century draws to a close, change is in the air for Waverly Place (天后廟街; canto: “Tin Hauh miu gaai”), one of San Francisco Chinatown’s iconic small streets.

In his book San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to its History & Architecture, historian Phil Choy wrote about the small street as follows:

“Waverly Place was originally known as Pike Street. Since the 1880s, local residents called it “Tien Hou Mew Guy” after the Tien Hou Temple located there. In the 1890s, the street was also home to the Kwan Kung Temple of the Ning Yung district association. On the opposite side of the street (22 Waverly) sat the Sing Wong Mew (Temple of the City God), while the Tung Wah Mew (Temple of the Fire God) was at 35 Waverly. . . .

“B 41. Chinese Josh-House, S.F., Cal., c. 1885. Photograph by I.W. Taber (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection). The adjacent buildings appear to be of wooden construction and far different than the temple’s neighboring structures on Waverly Place in the following decade.

“Westerners have often referred to Chinese temples as “Joss Houses” although the Chinese word for temple (in Cantonese) is actually Mew. The word joss is a corruption of the Portuguese word Dios for God, stemming from the time of Portugal’s colonization of Macau in 1557. ...

“The street was also known as “Ho Bu’un Guy” or “Fifteen Cent Street,” because of the barber shops providing tonsorial services for the price of fifteen cents.

The pulse of life on Waverly Place remained a popular subject for the photographers of the 19th century. I have written previously about the photographs of two of the principal and famous occupants of the street before and after the 1906 quake, namely, the Tin How Temple (to read more see here) and the Ning Yung district association’s headquarters (to read more see here).

“3546 The New Chinese Joss House, Waverly Place, San Francisco” c. 1887. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection). The photograph supposedly taken in 1887 by I.W. Taber shows the new Ning Yung headquarters at 25-35 Waverly Place (the construction of which other sources report was completed in 1890). Seen at the top is the temple containing a shrine to Guan Di (關帝; canto: Guān daì implies deified status) or "Lord Guan" (關公; canto: Guān Gūng), while his Taoist title is "Holy Emperor Lord Guan" (關聖帝君; Guān Sing Daì Gūan).

Detail from the city of San Francisco’s “vice map” of July 1885 (from the Cooper Chow collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America).

In this article, we will view some of the other street photographs which researchers seldom examine in any detail.

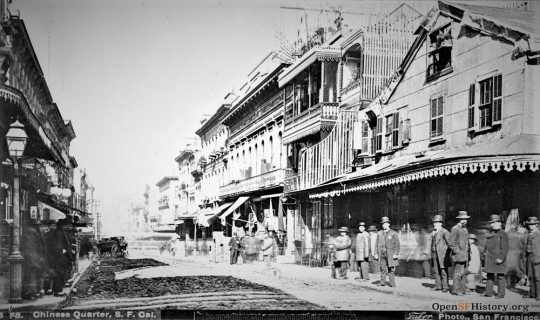

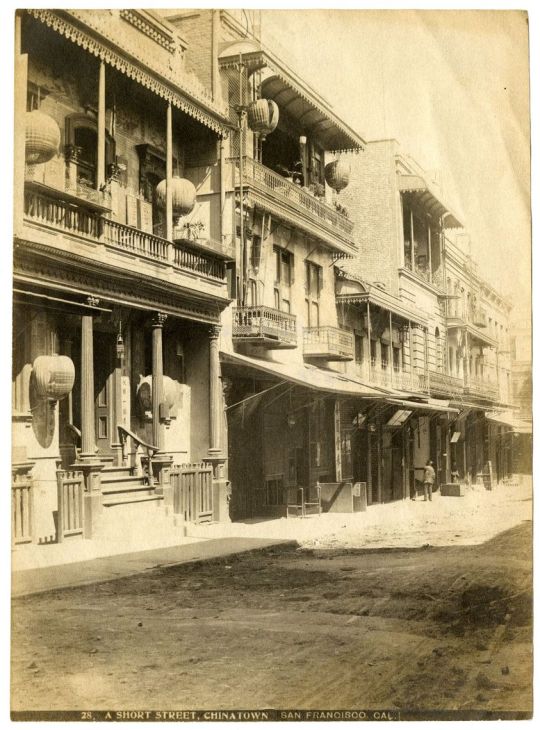

A view north on Waverly Place along its eastern side and toward its T-intersection with Washington Street, c. 1880s. Photographer unknown. An approximate year for this rare photograph can be ascertained by a study of old San Francisco Chinatown’s pawnshops which occupied both sides of the 800-block of Washington Street during this era. In this photo, a sign possibly inscribed with the characters 寶興押 (canto: “Bow Hing aap”) appears on the second floor balcony of the building at the end of Waverly. According to the Langley directory for 1883, a “Bow Hing & Co. general merchandise” store operated at 820 Washington Street, which would be consistent with the signage and indicate an additional pawnshop business. The light façade of the Chinese Grand Theater at 814 Washington Street appears in the center background of the image.

“B2694 Chinatown, S.F. Cal. The Joss Temple” c. 1889. Photo by Isaiah West Taber (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Some online sources date this photo as c. 1900, but the “Pacific Coast Scenery -- Alaska to Mexico Catalogue published by Taber in 1889 included this numbered “Boudoir” series image.

In this view of the Tin How temple at 33 Waverly Place taken from an elevated position on the south side of the street, several men can be seen hovering over a fortune teller’s divination table on the sidewalk in front of the temple. The large banner signage seen at the street level advertises the fortune-teller’s use of the 卦命 (canto: “gwah ming”) as his method of divination.

The temple of the Gee Tuck Tong (pinyin: ”Zhide tang;” 至德堂) can be seen at the right of the above photo at 35 Waverly Place. The Gee Tuck temple, dedicated to the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heavens, was reportedly founded during the mid-1880s.

Tien Hou Temple on Waverly Place, c. 1890 – Photo by Willard E. Worden

In this view of the west side of Waverly Place looking north to Washington Street, the top floor of the Gee Tuck Society (至德堂; canto: Gee Duck Tong) at 35 Waverly Place can be seen at the right: this temple had supposedly operated since the mid-1880s. By the time Worden took this photo, the wooden buildings adjacent to the Tin How Temple (天后古廟; canto: “Tin Hauh gǔ miu”) , seen at the left of the frame, had been replaced with masonry structures.

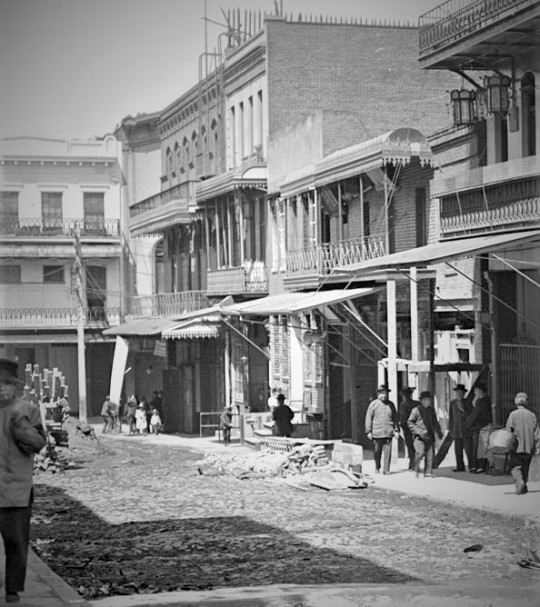

The view north from Clay Street up Waverly Place to its intersection with Washington Street in the distance, c. 1898. Photograph by Edwin Stotler (from the Edwin J. Stotler Photograph Collection / Courtesy of the Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives).

The view north from Clay Street up Waverly Place to its intersection with Washington Street in the distance, c. 1900. Photograph by Willard E. Worden. The sign for the Sze Yup Association can be seen above the balcony of the second floor of the 820 Clay Street building seen at left on the northwestern corner of the intersection with Clay Street.

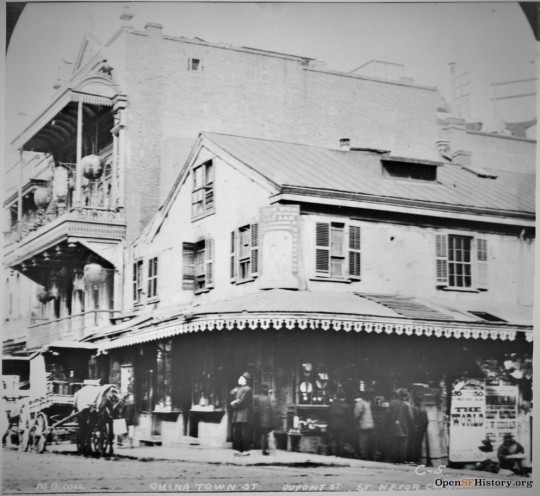

The northeast corner of the intersection of Waverly Place & Clay Street, c.1900. Photograph by Willard E. Worden. The view north on Waverly Place, back from cobblestone-paved Clay Street. The Yoot Hong Low restaurant building at 810 Clay Street can be seen at right.

For a closer look at the eastern side of Waverly Place in old Chinatown, see my article about the series of photos taken by Oscar Maurer and D.H.Wulzen of the more northerly end of the street here.

A mother and two children at the northwest corner of Waverly Place and Clay Street in San Francisco Chinatown, c. 1900 (Courtesy of the National Archives; photo also in the collection of the California Historical Society). The signage of a basement eatery for workers,芳記 (canto: “Fong Gay”) appears at left.

Variously entitled “The Mountebank,” “The Peking Two Knife Man,” or “The Sword Dancer,” c. 1896-1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Library of Congress).

“Genthe used various titles for this portrait of Sung Chi Liang, well-known for his martial arts skills. Nicknamed Daniu [canto: “dai ngau” or 大牛] or “Big Ox,” referring to his great strength, he also sold an herbal medicinal rub after performing a martial arts routine in the street. This medicine tiedayanjiu [canto: “tit daa yeuk jau” or 铁打雁酒]), was commonly used to help heal bruises sustained in fights or falls. The scene is in front of 32, 34, and 36 Waverly place, on the east side of the street, between Clay and Washington streets. Next to the two onlookers on the right is a wooden stand which, with a wash basin, would advertise a Chinese barber shop open for business. The adjacent basement stairwell leads to an inexpensive Chinese restaurant specializing in morning zhou [canto: “juk” or粥] or rice porridge.”

From Genthe's Photographs of San Francisco's Old Chinatown -- Photographs by Arnold Genthe -- Selection and Text by John Kuo Wei Tchen.

For reasons that are not entirely clear, the northern end’s east side of Waverly Place attracted less attention from Genthe and the photographers of the day. However, a closer study of the work of Oscar Maurer and D.H. Wulzen (as discussed here), allows researchers to place several of their photographs in the context of life and work on Waverly Place.

Untitled Chinatown street, c. 1898. (Photograph by Oscar Maurer (from the collection of the Oakland Museum of California, Museum Income Purchase Fund). Until now, no commentators were able to identify the location of this street scene on Waverly Place.

Fortunately for the researchers of old Chinatown, Maurer captured two crucial pieces of signage in his untitled 1898 photograph in the Oakland Museum which help in identifying the precise location in Chinatown of the buildings seen above. The first example can be seen in the vertical sign appearing at the left of the frame, containing the characters 致和堂參茸藥材 (lit.: “Gee Wo Ginseng Medicinal Herbs;” canto: “gee wo tong sum yung yeuk choy;” pinyin: “Zhì hé táng cān rōng yàocái”). The Horn Hong & co. Chinese business directory and lunar calendar for 1892 shows the Gee Wo Tong company located at 124 Waverly Place.

Detail from the Horn Hong & Co. Chinese directory for 1892 for the Gee Wong Tong company.

By the publication of the 1895 Langley directory the Gee Tau Hong & Co. and Gee Wo Tong & Co. shared the premises at 124 Waverly Place. The 1905 Sanborn map for this Chinatown street confirmed the presence of, and use of the property by, the Chinese herbalists. Having established the street on which the herbalists operated, the location of the basement eatery whose entrance signage can be seen in the center can be located with equal precision.

Moreover, by comparing Maurer’s photo with one by D.H. Wulzen of the same basement entrance, the full tradename of the eatery can be discerned as “Wah Ying Lung” 華英隆(canto: “wah ying loong”), a name which could also constitute literal shorthand for Chinese/English (or Chinese American). When viewed together, Mauer’s photo corroborates the partially-obscured address plate in the Wulzen photo as located at 120 Waverly Place.

Restaurant worker returning from a delivery to a basement eatery, c. 1900. Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). The last two digits of the address at 120 Waverly Place can be seen over the door to the basement entrance. The right portion of the sign advertises literally seasonal, i.e., 時款 (canto: “see foon”) food.

Having established the address of the Wah Ying basement eatery at 120 Waverly Place, the men seen in Maurer’s photo are standing on the landing of the stairs to 116 – 118 Waverly Place. Occupying a lot on the east side of the small street, and across from the Tin How temple and the headquarters and shrine of the Ning Yung district association, the building served as a boarding house. The 1905 Sanborn map confirmed its use as “lodgings.”

Detail showing Waverly Place in San Francisco Chinatown from the 1905 Sanborn Insurance Map (Vol. 1, Page 39-40) of San Francisco, prepared by the Sanborn-Perris Map Company, Limited, of New York.

A detail from “Waverly Place - April 9, 1900” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D. H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). This close-up looks north on Waverly Place from the intersection with Clay Street. Magnification of the center portion of the image shows the building elevation, the partial signage for the basement entrance to the Wah Ying eatery, and the stairs on which the trio of Chinese men stood for Oscar Maurer’s photo in 1898.

“The First Born” Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Library of Congress) The above photo was taken on the east side of Waverly Place with the Tin How Temple in the background. According to historian Jack Tchen, “[h]eaddresses were often red with pearls or jewels and a red fluffy pompom on top. Sometimes bells were attached so that when the child moved they would make a noise. Silk tassels often hung down on both sides. The difference between the headgear of boys and girls was that girls’ headdresses came down and covered their ears, whereas boys’ did not. Girls’ holiday clothing generally had embroidered edges absent from comparable clothing for boys.”

Whether by design or negligence, the street signage for Waverly Place only bears its Chinese name, 天后廟街 (canto: “Tin Hauh miu gaai”) on the standard located at the north end of the small street in 2022. Nevertheless, the name remains a tribute to a 170 year-old tradition of veneration of a Chinese pioneer deity. Photograph by Doug Chan.

Today, Waverly Place retains its legacy as a distinct, Chinese American street.

Waverly Place, October 9, 2021. Photograph by Doug Chan

“On Waverly Place,” wrote historian Phil Choy, “ there is a unique concentration of buildings that represent the different types of traditional Chinese organizations. Architecturally the contiguous line of buildings combining classical motifs with Chinese elements and color created a Chinese streetscape neither East nor West bur rather indigenously Sen Francisco.”

“A Bit of Old China, San Francisco, 1905.” Oil painting by Edwin Deakin (from the collection of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco).

[updated 2022-12-2]

#Waverly Place#San Francisco Chinatown#Tin How Temple#Ning Yung Association#Gee Tuck Tong#Phil Choy#Arnold Genthe#Willard Worden#I.W. Taber#Oscar Maurer#D.H. Wulzen#Wah Ying basement restaurant

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Chinatown, San Francisco California, 1895.” Photograph by Wilhelm Hester (from the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections). This photo shows a view north up Washington Place, a.k.a. Washington Alley (“Fish Alley” to English speakers) or “Tuck Wo Gaai” (德和街) to old Chinatown’s residents.

Washington Place: Chinatown’s “Fish Alley” 德和街

The street on which one of my grandmothers was born in 1898 had already begun to acquire a rich photographic legacy as an iconic alleyway whose south-north axis connected Washington to Jackson Streets in San Francisco’s old Chinatown. Prior to the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906, the city had designated the short street as “Washington Place.”

The photographers of old Chinatown often called the street (which would later be re-named Wentworth Place after the quake), as Washington Alley and “Fish Alley.” Chinatown residents referred to the alleyway as “Tuck Wo Gaai” (德和街; lit.: “Virtuous Harmony St.; canto: “Duck Wo gaai”), the name of a well-known business which was located at least as early as 1875 on the southwest corner of the “T” intersection of Washington Place with Jackson Street.

Fish Alley must be considered one of old Chinatown’s most famous streets, the images of which were captured by various photographers and artists during the 19th century. While far from complete, this article attempts to identify the businesses at each identifiable address from photos that are available online. The businesses operating on Washington Place during the latter decades of the 19th century established the small street as one of the iconic alleyways of the pre-1906 community. The photos are grouped roughly in the order they would have appeared to a pedestrian walking north on Fish Alley from Washington to Jackson streets.

“In the Heart of Chinatown, San Francisco, California” c. 1892. Photographer unknown, stereograph published by J.F. Jarvis (from the Robert N. Dennis collection, New York Public Library).

“In the Heart of Chinatown, San Francisco, U.S.A.” c. 1892. This enlarged photo from the original stereograph looks north up Washington Place or Alley, a.k.a. “Fish Alley,” from Washington to Jackson Street.

At least one motion picture of life on the street has survived to this day, a “Mutoscope” from April 1903. (See, e.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53DTuc6-1hI&ab_channel=LibraryofCongress)

A portion of the hand-drawn map by immigration officer John Lynch from 1894. Washington Street at the southern end of Washington Place appears at the top of the image.

The attempts by local historians to identify various places on Fish Alley has also been helped by the preservation of a hand-drawn immigration officer map from 1894 (the “1894 Map”), as well as numerous business directories showing the names and addresses of the businesses operating on this street prior to the destruction of the neighborhood in 1906.

“Chinatown, San Francisco, Cal.” C. 1890. Photographer unknown (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection). This photo was taken from Washington Street looking north up Washington Place (a.k.a. Fish Alley) toward Jackson Street.

“Street in Chinese Quarter – San Francisco” c. 1870s. Photograph possibly taken by the studio of Thomas Houseworth & Co. Image courtesy of Wolfgang Sell of the National Stereoscopic Association. This stereocard shows Emperor Norton (at right) on Chinatown’s “Fish Alley” a.k.a. Washington Place (looking north toward Jackson Street).

By the 1870’s, Fish Alley or Washington Place had already acquired its status as a destination to view in old Chinatown. No less than a local celebrity such as Emperor Norton would pose for a photo on an ever-busy fish and poultry venue.

Untitled photo of Washington Place (a.k.a. Fish Alley), no date. Photo produced by the studio of Isaiah West Taber (from the collection of the California Historical Society). The Tuck Hing meat market appears at the left on the northwest corner of the T-intersection of Fish Alley and Washington Street. The identity of the photographer holding his camera and tripod at the left-center of the image is unknown.

“B 2689 Provision Market in Alley in Chinatown, San Francisco” c. 1891. Photograph probably by Carleton Watkins but printed as a [I.W.] Taber Photo (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection). This photo shows a view north up Washington Place (a.k.a. Washington Alley or “Fish Alley” to English speakers) or “Tuck Wo Gaai” (德和街) taken sometime between 1880-1891. In a travel book in which the photo “The Provision Market [etc.]” appeared, the writer observed that the market “supplies a better class of food to customers than the markets in China itself. In China the shops sell, rats, mice, dogs, cats and snails; poultry is sold by the piece – so much for a leg, so much for a wing. In San Francisco food is more easily obtainable and money is not so scarce, so that the Chinaman lives better than in his own country… .”

“Chinatown at Night” published by Britton & Rey (from the collection of Wong Yuen-Ming). The postcard image was derived from the Taber Photo “B 2689 Provision Market in Alley in Chinatown, San Francisco” c. 1891.

The above photo and derivative postcard in this series was sold by Isaiah West Taber under the title “Provisions Market in Alley in Chinatown, San Francisco,” but the image was probably captured by Carleton Watkins and acquired by Taber in the aftermath of Watkins’ bankruptcy. The identity of the store shown at the left in the photo is well-known as the Tuck Hing meat market. The market appeared frequently in Chinatown directories from that era and the living memories of Chinatown’s oldest residents.

Listing for the Tuck Hing meat market at 746 Washington St. from the Horn Hong & Co. Chinatown Business Directory and lunar Calendar for 1892.

According to the directories and 1894 Map, the corner market was operated under the name “Tuck Hing Butchers” in a brick building at 746 Washington Street and its alley address at no. 2 Washington Place (in the Langley directory of 1895). The Tuck Hing meat market operated for about a century from 1888 to 1988 at the same northwest corner of the intersection of Washington Street with Washington Place (later named Wentworth).

Across the street from Tuck Hing, on the northeast corner of the intersection of Washington Place and Washington Street, a visitor to Fish Alley around the turn of the century would see another corner store, the Sun Lun Sang Co. at 1 Washington Place.

Fish Alley, no date. Photograph by Turrill & Miller from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection). The Sung Lun (or Lung) Sang, a.k.a. Sun Lung Sing (新聯生; canto: “Sun Luen Saang”) general merchandise store appears at right.

Listing for the Sun Lung Sang market at no. 1 Washington St. from the Horn Hong & Co. Chinatown Business Directory and Lunar Calendar for 1892.

“One Washington Place,” c. 1892-1896. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division). The store signage for Sun Lun Sang company (新聯生; canto: “sun luen saang”) appears along the left of the frame. The trees of Portsmouth Square and the tower portion of the Hall of Justice are visible through the open, south-facing window along Washington Street frontage.

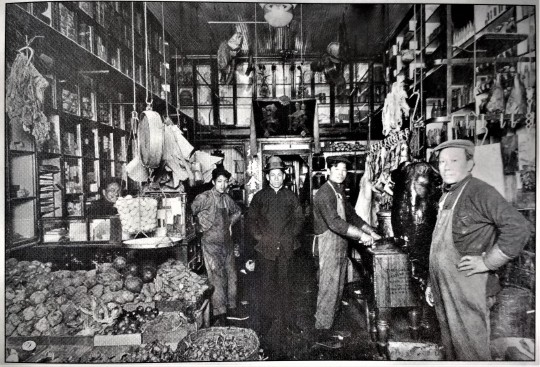

Historian Jack Tchen identified the store at the northeast corner of Fish Alley and Washington Street as the Sun Lun Sang Co. (新聯生; canto: “Sun Luen Saang” ) “Caged chickens are clearly visible on the right,” Tchen writes. “The photograph was probably taken during New Year’s, because the children are dressed in fancy clothing. The simply dressed woman looking on is probably a house servant to a wealthy merchant family.”

“One Washington Place” c. 1897. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division). “In this view, taken sometime after 1897,” Jack Tchen writes, “the store sign reads ‘Yow Sing & Co., No. 2.’The man in the basement stairwell is holding a Chinese scale (cheng). The wooden panels on the left are used to board up the storefront after business hours.”

“Chinatown – fish market, circa 1900.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). A fishmonger talks to a young shopper while cleaning a fish at his sidewalk cutting board probably at no. 5 or 6/12 Washington Place, a.k.a. Fish Alley.

“Fish Market, two men,” c. 1900. Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). The same fishmonger talks to a male shopper in front of the store at 5 Washington Place. The window of the barbershop has been scratched out at the right of the frame.

D.H. Wulzen’s photos of a fish store serving a child customer and a lone man fortunately captured a faint images of its business signage, i.e., 昌聚魚鋪 = (lit. “Prosperous Gathering”; canto: “Cheung Jeuih yu poh”; pinyin: “Chāng jù yú pù”). The small store had apparently established itself after the preparation of the 1894 immigration map and by the turn of the century, its address at no. 5 or 6-1/2 Washington Place can be determined by its neighbor, whose business name on its window can be read as 同德 (canto: “Tuhng Duck”), a barbershop located at no. 3 Washington Place.

Listing for the “Tong Tuck” barbershop at 3 Washington Place from the Horn Hong & Co. Chinatown Business Directory and lunar Calendar for 1892.

Several photos of Arnold Genthe provide the basis for a reasonable guess about the Chung Hing & Co. poultry store’s probable occupancy of the space at no. 4 Washington Place.

“Fish Alley, Chinatown, San Francisco” a.k.a. “Booth, Fish Alley, Chinatown, San Francisco” undated [c. 1895- 1905]. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division). “Freshly killed chickens are hanging from the rack,” writes historian Jack Tchen, “with wooden chicken crates visible in the background. Fish as redisplayed on the table to the right. An American-made scale is hanging in the upper left-hand corner of the photograph.”

In addition to his Fish Alley photo which appeared in two editions of his photos of old Chinatown, Arnold Genthe took at least two other wider-angle images of the Chung Hing & Co. store.

“Two women and a child walking down a sidewalk between crates, Chinatown, San Francisco” c. 1896- 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division).

This clumsily-named photo of a man and probably two daughters walking past a poultry store appears to be the same shop depicted in Genthe’s “Fish Alley” photo, at no. 4 Washington Place. Although two large lanterns adorn the entryway, the work table (at left), the scale and the basket of eggs suspended to the left of its entrance are identical.

“Vendors and a horse and cart on a street, Chinatown, San Francisco,” c. 1896- 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division). This photo represents the third image captured by Genthe of the poultry store probably located at no. 4 Washington Place, a.k.a. Fish Alley. The presence of the pair of lanterns over the entryway to the store indicates that it was taken closer in time to the preceding photo of a man and his daughters walking past this store.

Genthe’s photos from across the alleyway affords a better view of the building elevations. The “Vendors” photo probably depicts the west side of Washington Place or Alley on which the poultry stores operated. From left to right, one sees the Fish Alley store occupying the larger opening of a brick building, followed by a narrower entry opening, presumably leading to a stairway to the upper floors. The horse cart is parked in front of a wooden structure which abuts a two-story brick building with a light façade which, in turn, is adjacent another brick building. This combination of buildings, i.e., “brick-wood-brick-brick” more closely fits the line of structures starting at no. 4 Washington Place and proceeding sequentially as noted on the 1894 Map sketched by immigration officer John Lynch (the “1894 Map”).

“Fish Market, Two Men,” circa 1901. Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). Wulzen’s photo depicts the same poultry store seen in Genthe’s “Fish Alley” and related photos. The store’s poultry cages against the left wall of the interior are more visible in the background. The stairway to the upper floors appears more clearly in the center, and the Wulzen photo confirms the wooden construction of the adjacent building at right.

Fortunately, Dietrich H. Wulzen, Jr., shared with his photographic peers a fascination with the businesses which operated on old Chinatown’s Fish Alley. Viewing both images of the same store by Genthe and Wulzen allows the viewer to understand better the context of the built environment of Fish Alley and, in particular, the location of the poultry store at no. 4 Washington Place.

“Clerk at poultry market, chicken hanging,” circa 1901. Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). Wulzen took another photo of the Chung Hing & Co. poultry store at 4 Washington Place from a different angle and into its interior. The “clerk” seen dressing a bird appears to be the same man seen in the background of the previous photo in this series.

In his book Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco, art historian Anthony W. Lee wrote about Wulzen and “Fish Market, Two Men” as follows:

“[Wulzen] was especially attentive to Genthe’s pictures of these spaces in the quarter more frequented by the working class. Of his fifty-five plates, more than forty were shot in the alleys, including Fish Market, Two Men … photographed on Washington Place. It closely resembles Genthe’s picture of the same subject …, differing primarily in the angle of approach and the wares (fish, not poultry) that the vendor has displayed. Wulzen even carefully registers the sloping table and the slight angles of the two washbasins beneath it, just as Genthe had done.”

Unlike the case of several of his prominent contemporaries, Wulzen’s glass plate negatives escaped the destruction caused by the 1906 Earthquake and Fire, and his son Frank donated the negatives to the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) on the 90th anniversary of the disaster. The SFPL added Wulzen’s Chinatown scenes to its online offerings in 2016. Born in 1862, Wulzen became a pharmacist in 1889, studying at the Affiliated Colleges on Parnassus Heights. In the 1890s, according to the SFPL, he became interested in photography and added a Kodak Agency to his drug store. Wulzen joined the California Camera Club and became known for a photographic style which was “straightforward and realistic, unlike the dominant ‘artist’ photography of the club.”

“Chinese Fish Peddler, San Francisco Chinatown” c. 1900. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Monterey County Historical Society). This hitherto unidentified photo also appears to be the same shop at no. 4 Washington Place which had attracted the interests of photographers Genthe and Wulzen.

The 1894 Map identifies the shop at no. 4 Washington Place as the “Chung King poultry & fish” store, but the business listings of the day, such as the Horn Hom & Co. directory of 1892 lists the name as “Chung Hing” (祥興; canto: “Cheung Hing”), and the 1895 Langley directory denotes the name as “Chong Hing & Co., 4 Washington Alley.”

“The Fish Market” undated [c. 1895- 1905]. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division). A print of this photo is also known by the title “Fish Market Scales” (without attribution to Genthe) in the collection of the California Historical Society.

Based on the small sign appearing above the doorway on the right of the image, historian Jack Tchen identified the location of this scene as the Chong Tsui store (昌咀; lit. Prosperous Assemblage”; canto: “Cheung Jeuih”) at 5-½ Washington Place.

Examination of images by other photographers and the Horn Hom Co. business directory of 1892 indicate that Jack Tchen misidentified the store in his book about Arnold Genthe’s photographs. The Chinese signage over the main storefront entrance of the store shown in Genthe’s photo reads from right to left as 廣興 or Quong Hing (canto: “Gwong Hing”). The Quong Hing store was located at 7 Washington Place.

Listing for the “Qung Hing” meat market at 7 Washington Place from the Horn Hong & Co. Chinatown Business Directory and lunar Calendar for 1892.

Untitled photo of the Quong Hing store located at 7 Washington Place, c. 1892. Photographer unknown (from a private collector item on eBay). The sign for the store appears more clearly in the upper-right corner of this photo than as shown in the Arnold Genthe photo of the same store.

“Chinatown market, San Francisco California, 1895.” Photograph by Wilhelm Hester (from the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections). The sign appearing in the left of the frame reads 恆昌棧 (canto: “Hun Cheung Jan”; lit. “Lasting Prosperity store”), which occupied the space at no. 7 Washington Place or Alley.

To some readers, the Chinese character “棧” could also be interpreted to be an “inn” or a boarding house. However, the Langley directories of 1894 and 1895 (the same year during which Wilhelm Hester took his photograph of a group of men gathered outside this storefront), lists a fish purveyor, “Hung Chong John, 7 Washington Alley.”

Hester is perhaps best known for his documenting the maritime activities of the Puget Sound Region and his time spent in Alaska during the gold rush of 1898. According to the University of Washington archivists, the bulk of his photos of the early history of ships and shipping in Washington State were taken between 1893 and 1906. Born in Germany in 1872, Hester moved to the Pacific Northwest in 1893. He established successful photo studios in Seattle and Tacoma, principally taking and selling photographs of maritime subjects, as ships from around the world and their crews docked at various Puget Sound ports.

The listing for the Hung Chong John store in the Langley directory of 1895

It appears that the Hung Chong John business shared the same address as the Quong Hing store. The address-sharing was not uncommon for this building. At least as early as 1885 (when the city prepared its “official map” of Chinatown), the building at no. 7 Washington Place was subdivided by three businesses all with the same address.

Detail showing the subdivision of the building at no. 7 Washington Place in the San Francisco Board of Supervisors official map of Chinatown, July 1885 (from the Cooper Chow collection at the Chinese Historical Society of America).

Untitled photo of the west side of Washington Place (a.k.a. “Fish Alley), probably in the morning. Photographer unknown. The wooden structure at left probably served as the shop spaces for the Kim Kee and Man Hop stores occupying the addresses at no. 6 - 8 Washington Place.

Unfortunately, the Langley directory of 1893 omits a separate Chinese directory and appears to have excluded Chinese businesses from its general listings. Based on its omission from the Horn Hong & Co. directory/calendar of 1892, the Hung Chong John store’s 1894 listing validates the year of 1895 during which Wilhelm Hester reportedly took his set of photos of Chinatown’s Fish Alley along Washington Place.

“Chinatown – fish market, c. 1900.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). D.H. Wulzen’s no-nonsense approach produced vivid images of one store in particular, the Hop Chong Jan company, located at 12 Washington Place.

D.H. Wulzen took at least three versions of his “Fish Market” photo (one of which is reversed on the SF Public Library website). The business sign on the middle column of the storefront reads as follows: 合昌棧 (canto: “Hop Cheung Jaanh”; pinyin: “Hé chāng zhàn”). According to the 1894 Map, a business named “Hop Chong Jan & Co.” was located on the east side of the street at no. 12 Washington Place (a.k.a. Fish Alley).

Detail from 1894 map of Washington Place or Alley by immigration officer John Lynch (from the collection of the National Archives).

Listing for the Hop Chong Jan market at 12 Washington Place from the Horn Hong & Co. Chinatown Business Directory and Lunar Calendar for 1892.

“Chinatown – fish market, c. 1900. Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). The business sign on the middle column of the storefront in this image is more faint, but the Chinese characters of 合昌棧 (canto: “Hop Cheung jaanh”; pinyin: “Hé chāng zhàn”) can be discerned.

The Hop Chong Jan company store also inspired other camerapersons to photograph its daily operations. The upper level of the building in which the Hop Chong Jan company at no. 12 Washington Place featured a wrought-iron balcony. The balcony grillwork enhanced interest in this building, as it figured prominently in other photographs and postcards from that era.

“Fish Alley, Chinatown” c. 1900. Photographer and postcard artist unknown, published by Edward H. Mitchell of San Francisco). Although unidentified, the postcard depicts the Hop Chong Jan company at no. 12 Washington Place. The details seen in the card are extraordinary, as they include sidewalk items seen in the photographs of the same building by D.H. Wulzen.

Untitled, San Francisco Chinatown, c. 1900. The sign on the column of the storefront 合昌棧 (canto: “Hop Cheung jaanh”; pinyin: “Hé Chāng zhàn”) can be seen in the center for the Hop Chong Jan fish market at no. 12 Washington Place.

“Chinatown market, San Francisco California, 1895.” Photograph by Wilhelm Hester (from the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections). In this view of two men in front of the store at no. 12 Washington Place, looking toward the southeast from the middle of the alleyway, the sign on the column (in the right half of the frame) faintly reads 合昌棧 (canto: “Hop Cheung jaanh”; pinyin: “Hé Chāng zhàn”) for the Hop Chong Jan fish market.

“Chinatown market, San Francisco California, 1895.” Photograph by Wilhelm Hester (from the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections). In this closer view of two Chinese and one white man in front of the store at no. 12 Washington Place, looking toward the southeast from the middle of the alleyway, the store’s sign cannot be seen. The presence of two lanterns from under the balcony’s overhang indicates that this photo was taken of the Hop Chong Jan (合昌棧; canto: “Hop Cheung jaanh”; pinyin: “Hé chāng zhàn”) market at a different time. Certain details such as the window at left, the hanging scale, and the display shelves are identical to Hester’s other photos of the store.

“Chinatown, San Francisco California,” c. 1895. Photograph by Wilhelm Hester (from the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections). In this street scene showing two Chinese American men and a child in front of a market, the view is of no. 12 Washington Place, looking south down the east side of the alleyway toward Washington Street. Certain details such as the window at left, the hanging scale, and the display shelves are identical to Hester’s other photos of the Hop Chong Jan 合昌棧 (canto: “Hop Cheung jaanh”; pinyin: “Hé Chāng zhàn”) market.

Untitled photo of Washington Place, a.k.a. Fish Alley, in pre-1906 Chinatown. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The photo shows almost the full elevation of the building at no. 12 Washington Place on the east side of the short street, looking north toward Jackson Street. To the right of the store frontage, a door and an interior stairway appears in virtually all images of the building at no. 12 Washington Place. The stairs presumably lead to the upper floors of the building. My grandmother, Lillian Hee, was born in one of upper apartments above this store on October 31,1898.

“Chinatown – fish market on Dupont Street, circa 1900.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library).

Wulzen’s photo of a fish market fortunately included the signage for “Hop Sing – clams” in the left of the frame. The San Francisco Public Library’s information that this market was located on Dupont Street is probably erroneous for at least several reasons. The 1894 Map by immigration officer John Lynch placed a “Hop Sing fish" company as located at No. 13 Washington Place (a.k.a. Fish Alley), on the west side of the street. Lynch also included a notation that the building was of “wood” construction, and Wulzen’s photo supports that conclusion. Moreover, the low-rise aspect of the building in the photo appears inconsistent with the higher elevation structures on Dupont Street in Chinatown. The Langley business directory of 1895 tends to support Lynch’s finding, although it lists a “Y Sing & Co.” at 13 Washington Alley, which might have been a typographical error.

“Chinatown – fish market, circa 1900.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). For this close-up shot of the same Hop Sing market (no. 13 Washington Place), the San Francisco Public Library has produced no evidence backing its claim of a Dupont St. location.

“Fish Market, One man sitting, "HOP SING CLAMS" sign,” circa 1900.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). This third shot of the Hop Sing market (at 13 Washington Place shows its operator during a lull in customers. The San Francisco Public Library also incorrectly identifies the location of the market on Dupont Street.

“Chinatown – fish market, circa 1900.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). Fortunately, the photograph shows a portion of the business sign above the man holding a scale and which was largely obscured by the store’s awning. According to the 1894 map and the Horn Hong & Co. directory of 1892, the Quong Shing (廣城; canto: “Gwang Sing”) store was located at no. 15 Washington Place. The 1894 map described the “Quong Shing & Co.” as a small general merchandise store.

“Fish Market, a woman watches a man weigh fish,” c. 1900. Photograph by D. H. Wulzen (from the D.H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library). From a slightly different angle as the preceding photo, Wulzen took a second shot of the Quong Shing (廣城; canto: “Gwang Sing”) store was located at no. 15 Washington Place.

“Fishmonger.” Photographer unknown from the collection of the California Historical Society). The proprietor of a fish store provides an unusual smile in this photo taken on old Chinatown’s Fish Alley. The only clue to the store’s location are provided by the business signage in the upper center of the image and above a handwritten number “22” on the inside left wall of the shop entrance: a fanciful Chinese name 老倌 祥城魚棧客 (lit.: “Old Shepherd Felicitous City Fish Store”; canto: “Low gwun cheung sing yu jahn haak”; pinyin: Lǎo guān xiáng chéng yú zhàn kè).

The store at no. 22 Washington Place was located almost in the middle of the block on the eastern side of the street. Unfortunately, only the prior occupant of the storefront space was not noted on the 1894 Map, and the name of a predecessor business (“Tong Yuen Hing”) appears in the Horn Hong & Co. directory of 1892 at the address.

The middle portion of the hand-drawn map of Washington Place or Alley by immigration officer John Lynch from 1894. The southerly end of the alleyway appears at the top of the image.

The last third of the hand-drawn map of Washington Place or Alley by immigration officer John Lynch from 1894. The northerly end of the alleyway at Jackson Street appears toward the bottom of the sketch.

A portion of “No. 145. Chinese Restaurant, San Francisco. Cal.” c. 1875. Stereograph by J.J. Reilly (from the collection of the Oakland Museum of California). The barely discernible Chinese characters on the glass lanterns of the second floor balcony further attest to the restaurant’s name as 聚英楼 or, Cantonese pronunciation, “Jeuih Ying Lauh”). The Bishop directory of 1875 confirms that the English rendering of the restaurant’s name was “Choy Yan Low,” and its address listing read as follows: “restaurant SE cor [sic] Washington alley and Jackson.”

According to the maps of that era, the southeast corner of the intersection corresponded to the address of 633 Jackson Street. As indicated by the 1894 Map, gambling establishments dominated the northern end and eastside of Washington Place (as the pattern that appeared in the “vice map” prepared by the city in July 1885). Not surprising, three men can be seen standing on the eastside sidewalk of Washington Place (at right); they are positioned near the entrances to the gambling parlors.

Detail of the north end of Washington Place from the July 1885 “vice map” of prepared by San Francisco.

Untitled photo of the northern end of Washington Place, a.k.a. Fish Alley or Tuck Wo gaai, looking south from Jackson toward Washington Street, c. 1890s. Photographer unknown. The Tuck Wo (德和) market for which the short street of Washington Place was named by the Chinese, occupied the southwest corner of the intersection partially seen in the foreground and to the right of the frame (at 635 Jackson Street). The entrances to gambling parlors were located along the east side of the alleyway at the northern end of Fish Alley and across from the alleyway frontage of the Tuck Wo market.

“The Butcher, Chinatown, San Francisco” undated [c. 1895- 1905]. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division). Genthe mistakenly titled this photo, as the man working over the table is fileting fish from his storefront on Washington Place, a.k.a. Fish Alley.

“Fish Alley, Chinatown. San Francisco, California” c. 1905. Postcard probably based on a photograph by Charles Weidner. The view appears to look north on Washington Place, a.k.a. Fish Alley, in old Chinatown.

The status of Washington Place as “Fish Alley” as a fish and poultry destination appeared to have endured until the earthquake and fire of 1906. The small street suffered the same fate of obliteration as every other street in old Chinatown. As Will Irwin wrote about this lost street of old Chinatown (while offering nothing substantial about the Chinese themselves): “Where is Fish Alley, that horror to the nose, that perfume to the eye?”

“Fish Alley, Chinatown” c. 1898. Drawing by A.M. Robertson (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). In this artist’s rendering the markets on Washington Place of old Chinatown, the building at no. 12 is seen in the center, the birthplace of my grandmother in the same year this drawing was published.

In Chinatown today, the sign for the old alleyway still bears the old Chinese street name from the pioneer era.

The street sign for Wentworth Place on the northwest corner of its intersection with Washington Street, June 22, 2022. Photo by Doug Chan. The sign still bears the Chinese name for the small street,德和街(canto: “duck who gaai”), the name of an old Chinatown business which occupied the southwest corner of the “T” intersection of Wentworth Place and Jackson Street from at least 1875 to 1906.

Wentworth Place, May 14, 2021. Photograph by Doug Chan. The city renamed Washington Place, a.k.a. Washington Alley or “Fish Alley,” to Wentworth Place after Chinatown was rebuilt in the wake of the 1906 earthquake and fire. Since at least 1875, Chinatown’s residents have called this small street connecting Washington to Jackson streets as “Tuck Wo Gaai” (德和街).

Recollections of the now-legendary Fish Alley of old Chinatown have faded from living memory. Many, if not most, Chinatown residents are unaware of the street name’s origin.

Former Supervisor, Board of Education commissioner, and attorney Bill Maher on Wentworth Place between the rainstorms contemplates the small street of my grandmother's birth in 1898 as a third-generation Californian, Jan. 4, 2023. Photograph by Doug Chan. Once known as Washington Place and “Fish Alley” to English speakers, the street sign still bears the old Chinese urban pioneer name of “Tuck Wo St.” (德和街; canto: "Duck Wo gaai") for today's residents of San Francisco Chinatown.

The vitality of the small street, however, not only lives on with the stories and the old images of its past, but Wentworth Place also serves as the home of the “Lion’s Den Bar and Lounge.” As the first genuine nightclub to open in almost a half-century in Chinatown, its establishment might one day be regarded as one of the events which sparked an economic revival in the neighborhood.

Fish Alley: it’s where we began; it’s where we’ll begin again.

[updated 2023-1-6]

#Washington Place#Fish Alley#Tuck Wo Gaai#Washington Alley#1894 immigration map#Emperor Norton#I.W. Taber#Arnold Genthe#D.H. Wulzen#Tuck Hing market#Sun Lun Sang Co.#Yow Sing & Co.#Chong Tsui store#Quong Hing#Hung Chong John#Hop Chong Jan#Hop Sing fish co.#Quong Shing#Chung Hing a.k.a. Chong Hing & Co.#Frmr. Supervisor Bill Maher

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Dupont & Clay Sts. San Francisco, Cal” c. 1900. Postcard probably published by Britton & Rey, San Francisco (from the private collection of Wong Yuen-Ming).

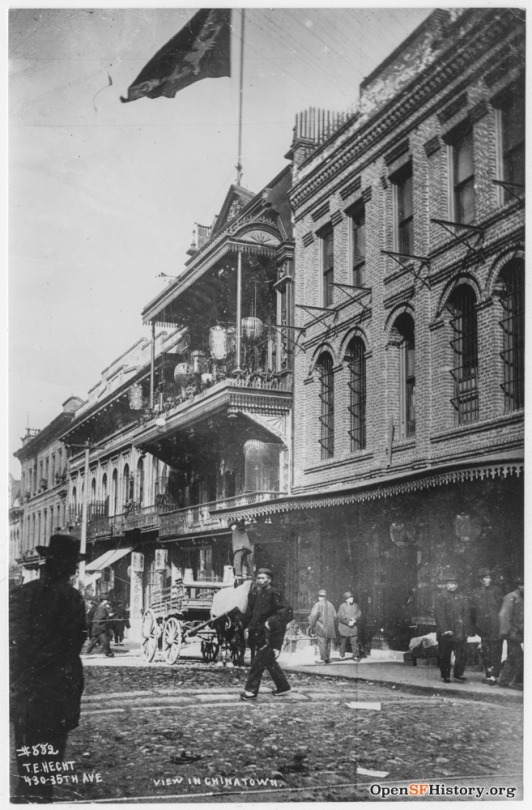

The Painted Balconies of Yoot Hong Low on Clay Street

The photographers of old San Francisco Chinatown displayed a fascination with the north side of Clay Street between Dupont Street and Waverly Place. Unfortunately, the black and white photos of the late 19th and early 20th centuries impart little about the true appearance of what photographer Arnold Genthe would call a “street of painted balconies.” The artwork found on the tourist postcards at the turn of the century conveys some sense of the building façade that regaled visitors to this particular block of Chinatown before the disaster of 1906.

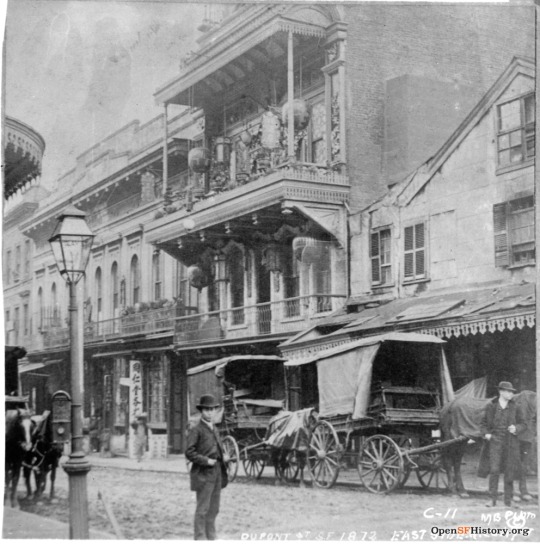

“Dupont Street, Principal Thoroughfare of Chinatown, S.F.” Postcard (466), dated May 17, 1904, published by Britton & Rey, San Francisco (from the private collection of Wong Yuen-Ming). The photographic record for this colorful building at 810 Clay Street shows clearly that the postcard’s caption misidentified the street. Other variants of the card corrected the postcard’s caption in subsequent or other printings. The handwriting on the card from 1904 by the original purchaser and sender of the card informs the recipient: “This is where we had Chinese tea yesterday.” Moreover, the small pennant, hanging from the left corner of the second floor (or first story) balcony -- more visible in photographs from this era -- confirms the presence of a tea house (茶居; canto: “cha geuih”).

The building at 810 Clay Street in Chinatown, San Francisco, c. 1890. The photograph has been attributed to I.W. Taber (from the Cooper Chow collection at the Chinese Historical Society of America). This photo shows the presence of an engraver's business name on the storefront window that would help date the photo to the late 1880′s or earlier. This photograph is frequently identified as a “joss house.” However, the presence of a restaurant on the upper floor is already evident during this period. The vertical signage appearing along the length of the left store window advertises 包辦酒席占点心餅食俱全 (canto: “bau bun jau jik jeem dim sum behng sihk geuih chuen”) or 包辦酒席 = arranged banquets; 點心餅食 = dim sum bakery; or 俱全 everything or complete.

Prior to 1900, the striking décor of the building at 810 Clay Street had already attracted the attention of photographers who often mistook its only use to be a joss house or temple. The identification as a joss house might have been correct for the pre-culinary uses of the structure or as an ancillary use. Moreover, researchers of the temples of pre-1906 Chinatown have speculated that an unknown temple operated somewhere in the 800-block of Clay Street at the approximate location as noted as location #17 on the 1885 map at this website: https://peterromaskiewicz.com/2020/06/02/map-of-temples-in-san-franciscos-chinatown-1850s-1906/

“Clay St. bet. Dupont & Stockton Sts. 1885.” Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Assuming that the year indicated on the border of the photo is correct (the Bancroft Library’s title contains a discrepancy, i.e., a 1895 date), this would have been the same 800-block of Clay Street between Dupont and Waverly Place as viewed by the special committee of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors published its public health map of Chinatown in July 1885.

Detail of the 800-block of Clay Street between Waverly Place and Dupont Street from the July 1885 map published by a special committee of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors (from the Cooper Chow collection at the Chinese Historical Society of America).

Prior to 1900, the Chinese restaurant located at 810 Clay St. was probably the Quen Fong Low restaurant which had been operating even before the San Francisco Board of Supervisors’ special committee published its Chinatown map of July 1885. The documentary record indicates that a restaurant had operated in the building at 810 Clay Street well before 1885. The Wells Fargo Chinese business directory of 1882 shows a “Quen Fong Low, Restaurant” operating at 810 Clay Street (as does the Langley directory of the same year (but listed as “Qun Fong Low”).

The listing for “Quen Fong Law, Restaurant” from the “Wells Fargo Directory of Chinese Business Houses” 1882. Courtesy of the Wells Fargo Bank History Room. The Chinese portion of the listing reads: 羣芳楼茶居酒宴企利街 810号 (canto: “Quen Fong lauh cha geui jau yeen kay lay gaai no. 810“), or “Quen Fong tea house and banquet 810 Clay St.”

“Oriental Building” c. 1890-1891. Stereograph by Charles R. Savage (from the Harold B. Lee Library of Brigham Young University, L. Tom Perry Special Collections). Although the street number of “810” can be seen clearly in the right storefront window, this stereograph and its cropped version of the photo has reposed for decades in the BYU archive without any sufficient identification of the building. The Chinese signage also indicates the location of a restaurant, i.e., 包辦滿漢葷素戲筵酒席 (canto: “bau bun wun hon fun so hay yeen jau jik”; pinyin: “Bāobàn mǎn hàn hūn sù xì yán jiǔxí”) or “banquet arrangements for Manchu and Chinese meat and vegetarian food.”

Several newspaper articles during the period from 1884 to 1895 mention restaurant operations at 810 Clay Street and imply that another eating establishment shared the premises with the Quen Fong Low restaurant. The Daily Alta California on November 21, 1884, reported as follows:

“The Chinese are not to be outdone by their American admirers in the matter of restaurants, as the new Chinese restaurant of San Fong Low, at 810 Clay street, is receiving such gorgeous decoration that it is said that when it is completed and the house is furnished the total expense will approach $20,000.”

The quoted value of the decorative improvements to the restaurant would cost approximately $584,981.44 in today’s dollars. Thus, it was hardly surprising to read a year and a half later that disputes about the furnishings and furniture of the restaurants spawned litigation. The Daily Alta California reported on March 20, 1886, reported the following item about a property repossession gone awry:

“Suit for recovery of property and costs, or damages in default thereof, has been begun through his attorney, David McClure, by Chin Ah Tim against Peter Hopkins. The property, valued at 20,000, is the contents of a large Chinese restaurant at No. 810 Clay street, which defendant, it is alleged, unlawfully attached or took into his possession. If a return of the property is made, the plaintiff will be satisfied with $3,000 damages and costs, the former being by way of recompense for the loss of business sustained since the 4th.”

“Chinese Store San Francisco” c. 1890-1891. Cropped photograph by Charles R. Savage (from the Harold B. Lee Library of Brigham Young University, L. Tom Perry Special Collections). An important clue appears above the street number 810 which can be seen in the right display window, i.e., the name of the business of “Q_?_n Fong.” The contemporary business directories list a restaurant under the name of Quen Fong Low or Qun Fong Low during the approximate period during which the photo was taken. The lanterns, window enframements, and other decorative additions to the upper balcony comprise a striking appearance and represent perhaps the highpoint of the building facade’s adornments. The lanterns themselves provide an additional clue about the name of the restaurant; the lower character appears to be 芳, i.e., one of the characters in the Quen Fong restaurant name (羣芳楼; canto: “Quen Fong lauh”).

“S.F. Chinatown 1894. C-14” (Photographer unknown from the Martin Behrman collection and the San Francisco Public Library Historical Photograph Collection. The California Historical Society attributes the photo to I.W. Taber.) Two men walking in opposite directions pass each other on Clay above Dupont Street and in front of the building at 810 Clay, c. 1894. A variant of the large vertical sign that would denote the presence of a restaurant for decades is partially obscured, as it reads包辦酒席点… (canto: “bau bun jau jik dim …”) or “arranged banquets and dim [sum] ….” Unlike later photos, the lanterns in front do not bear the name of the Yoot Hong Low restaurant. However, the Chinese character for Yoot Hong Low, i.e., 悅香樓, appear on a wooden sign above the more visible white vertical sign. Ascribing to the photo the year 1894 appears to conflict with newspaper reports and the absence of any directory listing for the year.

By the mid-1890’s, the ownership or operation of the restaurant at 810 Clay Street appeared to have changed. In the circa 1894 photo in the San Francisco Public Library collection (seen above), the lanterns have been changed at the ground floor level, and the Quen Fong Low name is nowhere evident. Assuming that the year written on the 1894 photo from the Martin Behrman collection is correct, the Yoot Hong Low restaurant had established itself in 810 Clay St. as early as 1894. However, the name appears nowhere in the 1894 and 1895 Langley directories for Chinatown. Moreover, the names of other restaurants appear in newspaper reports for the address at 810 Clay Street, such as a 1896 report mentioning a “Yet Ting How” restaurant (which could be a white reporter’s corruption or mishearing of a Chinese name).

Moreover, a newspaper account about a series of police raids as reported in The San Francisco Call newspaper on January 25, 1895, indicates that whatever restaurant was operating at 810 Clay Street may have also shared the building with one or more tongs.

WAR GODS IN PRISON.

The Police Dethrone Them in Chinatown. TO SUPPRESS HIGHBINDERS. -- Chinese Merchants Menaced by the Hatchet Men. SO MANY RAIDS ARE MADE IN TIME. -- Headquarters of Seven Gangs of Desperadoes Demolished in Presence of Their Occupants.

The Chinese god of war was made to bite the dust last night in more places than one, while horrified highbinders looked on in amazement. It was the grand inauguration of New Year festivities in Chinatown. The streets were bright with colored lanterns and the pungent odor of burning punk ascended from a hundred shrines. Every nook and corner was packed with Mongolians and white visitors, and the many highbinders were preparing for a veritable harvest of blackmail and its inevitable accompaniment in Chinatown murder.

In seven places these outlaws were gathered. Some of them had built altars and enthroned idols decked with grotesque metal ornaments, urns and gorgeous oriental embroideries. Only the war god, the fierce unconquerable hero who presides over the destinies of all belligerent Chinese, was thus honored by them, but hardly were the altars finished before squads of policemen with axes in hand dashed in and demolished them.

This wholly unexpected action of the police created consternation among the binders. Sergeant Gillan and his men made a similar raid about ten days ago when informed by Chinese merchants that unless prompt measures were taken to suppress the desperadoes an outbreak might occur any day before the present festive time came to a close. Several signs and insignia of the highbinders were then confiscated. Sergeant Gillan was told early yesterday that the respectable element of Chinatown was greatly excited by an influx of well-known highbinders from Stockton and Fresno.

"I received notification," said the sergeant, "that gangs of desperate characters had arrived and a systematic blackmail of merchants was in order. The object was to get money for the New Year orgies and to support several highbinder societies. So I made an investigation quietly and found that the highbinders had hung out signs and opened headquarters. I also saw enough to convince me that these fellows meant business."

The police waited for night to come before making a simultaneous raid on the hatchet men's headquarters. Policemen McManus, Lynch and Ellis raided the Dock Tin Tong, at 810 Clay street, and captured a war joss, which the Mongols tried to hide. The altar, code of laws and other paraphernalia were confiscated. At 35 Waverly place the Say Teen Tong resort was broken into and denuded of its signs and papers. The Hig Sig highbinders, at 70-1/2 Spofford alley, were next raided.

At the same time Sergeant Gillan and Policemen Tuite and Duane surprised the Sam Ducks at 6 Ross alley, the Ben On Tong at 815-1/2 Jackson street, the Wah Ting Sang Tong at 1018 Dupont street, and the Kai Sen Shea Tong at 819-1/2 Washington street. The Kai Sen Shea highbinders had an elaborate joss house. Their altars were decorated with costly metal vessels, vases and candlesticks and draped with magnificently embroidered silks, and all around were condemnatory pictures and signs in frames.

While the police were gathering up everything portable the highbinders hid their war god beneath an ebony table. But the police knew from experience that it breaks the spirit of the ruffians to carry off the joss and a hunt for the god followed. A howl of imprecations burst from the maddened outlaws when the joss was found and confiscated.

No more desperate society exists in Chinatown than this same Kai Sen Shea, which, the police say, has a bad record. The Ben On Tong is similarly dreaded by the peaceable Chinese, for its hatchet men bear a reputation for absolute disregard for life and law.

The San Francisco Call newspaper on January 25, 1895

A news item about a double homicide as reported in The San Francisco Call newspaper on October 6, 1896, contains a clue about the name of the restaurant which had replaced Quen Fong Low in 810 Clay Street. The Call reported that one of the victims had been gunned down while on a delivery run for a “Yet Ting How restaurant.”

The San Francisco Call newspaper on October 6, 1896, containing the full story of “Two Murdered by Pagan Assassins” and the shooting of a waiter from the Yet Ting How restaurant at 810 Clay Street.

Clay Street, looking west up the hill from Dupont Street, c. 1900. (Photographer unknown from a private collector).

The restaurant at 810 Clay Street can be seen in the background, left of center. The lack of visible Chinese characters on the two lanterns above the entrance to the building suggest that the photo was taken during the same period as the preceding photo from the Martin Behrman collection. Thus, the photo probably predates 1900.

The northeast corner of Waverly Place and Clay Street, c. 1890s. Photographer unknown from a private collector). The restaurant at 810 Clay can been seen in the right side of the frame. In contrast to later photos of the restaurant building no lanterns have been hung above the entrance to the building. Thus, the photo probably predates the late 1890’s.

810 Clay Street appears in the center of the photo of the north side of Clay Street between Waverly Place and Dupont Street, c. 1890s. Photographer unknown. The photograph offers important clues about the name of the restaurant which preceded the better-known Yoot Hong Low restaurant, as the signage above the groundfloor entrance and on the second floor balcony bears a fanciful name, 一品香 (canto: “Yat Bun Heung”) or literally, “one fragrant taste.” During this time, and according to the Langley directory of 1895, a “Yoo Hing” bakery was also located at 810 Clay Street, probably on the ground floor or in the basement.

Clay Street between Waverly Place and Dupont Street, c. 1899-1900. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Negative Collection). This photo served as the inspiration for at least two color tourist postcards by Britton & Rey. The name “Yoot Hong” appears above the address number 810 on the left storefront window. Below the street number appear the words “General Merchandise.” The Yoot Hong name appears and in Chinese characters on the two large lanterns hanging above the building’s entrance photo, and this suggests that the business name of Yoot Hong may have originally denoted a store, and not a restaurant use, on the ground floor prior to 1900.

“Chinese Joss House before the Fire.” Photographer and precise date are unknown. The caption reflects the common and mistaken identification of the building at 810 Clay Street often depicted in photo archives and books as a temple. A fragment of the business name, i.e., “Yoot,” can be discerned in the left storefront window, indicating that the photo may have been taken sometime during 1900 when the Yoot Hong Low restaurant had begun operations in the building.

By the summer of 1900, the Yoot Hong Low Restaurant (悦香酒樓; canto: “Yuet Heung Jauh Lauh”) was operating in the building at 810 Clay Street. Yoot Hong Low reportedly occupied several floors; its basement typically served simple dishes to workers at simple wooden tables; and the top floor dining rooms were typically reserved for enjoyment by the more prosperous merchants and their guests. The writing on the lanterns identifies the ground floor as 悦香酒樓 or Yuet Heung Restaurant.

“The Street of Painted Balconies” c. 1900. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). By boosting the lighting of this Genthe photo of the restaurant from the Library of Congress, the small sign suspended on the second floor balcony denotes that part of the building as a 茶居 (canto: “cha geui”) or tea house.

The long vertical sign at the left vertical frame of the Yoot Hong Low restaurant’s façade shows the final form of the advertisement that appeared in photos during the 1900-1906 period, i.e., 包辦酒席占点心餅食俱全 (canto: “bau bun jau jik jeem dim sum behng sihk geuih” etc.) or 包辦酒席 = arranged banquets; 點心餅食 = dim sum bakery; or 俱全 everything or complete. With the advent of telephone service through the Chinese Exchange, the directory for the year 1900 listed the phone number for the establishment as “China 26 Yoot Hong, restaurant 810 Clay.”

“The Crossing” c. 1900. Photo by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). When Genthe photographed three children in holiday attire crossing Clay Street from the southeast corner of its intersection with Waverly Place, he also captured the image of the Yoot Hong Low restaurant with its large lanterns in the left background. The storefront windows have been covered by wooden shutters, indicating that the restaurant perhaps on that day was closed for the New Year holiday. The Clay Street streetcar tracks are visible in the street; the railway posed a potential hazard to children crossing the street, and the older girl has held both of the younger children close.

“A Family from the Consulate, Chinatown, San Francisco,” c. 1900-1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

A father and son (with a balloon), attired as befitted a merchant family, walking west on the north side of Clay above Dupont Street. More modestly-dressed passersby stare at the pair, perhaps in recognition of the man’s status as a consular official. The long vertical signage parallel to the drainpipe in the left-hand part of the image has been damaged. Other photos from this period show the complete sign as 包辩酒席占点心餅食俱全 (canto: “bow bin jau jik tin dim sum behng sihk geuih chuen”) or 包辦酒席 “= can host banquet;” 點心餅食 “= dim sum bakery;” 俱全 “ = both or complete.” The shuttered storefront of Yoot Hong Low restaurant’s premises at 810 Clay Street indicates that the building is closed for the New Year holiday.

The north side of Clay Street near Waverly, c. 1900. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Negative Collection). This photo served as the inspiration or template for at least two postcards published by the Britton & Rey company of San Francisco. The name of the restaurant Yoot Hong Low appears in the left storefront window above the address number of 810 Clay Street. The typical restaurant signage of the day of 包辩酒席占点心餅食俱全 (canto: “bow bin jau jik tin dim sum behng sihk geuih chuen”) or 包辦酒席 “= can host banquet;” 點心餅食 “= dim sum bakery;” 俱全 “ = both or complete” is partially obscured by a pedestrian walking east, down the hill. A small pile of wood can be seen at curbside in front of the restaurant, indicating the eatery’s reliance on wood for its fuel.

This photo of unknown provenance (and briefly seen on the eBay website), captures the delivery of wood to the Yoot Hong Low restaurant on the north side of Clay Street, c. 1900. The deliveryman appears to be waiting for admission to the premises and carrying his load of wood by use of a carry-pole. Wood carriers were a common sight in old Chinatown. The city of San Francisco attempted to ban the use of carry-poles on sidewalks as early as 1870, but workers often found a way around the law by simply walking in the street with their loads.

A view west from the southeast corner of the intersection of old Dupont and Clay Streets, c. 1900. Up the hill, and in the left half of the frame, one can see the intersection of Clay St. and Waverly Place. The Yoot Hong Low restaurant’s balconies can be seen in the left-center of the frame (and a couple of doors down from the intersection of Clay Street with Waverly Place. This lantern slide by an unknown photographer reposes in the collection of the Oakland Museum of California. Unfortunately, the OMCA has displayed a reverse image here, thereby baffling viewers of the pre-1906 photographic record of Chinatown for decades.

“Chinatown – Clay Street toward Dupont Street, August 24, 1901.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen from the D. H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

D.H. Wulzen photographed the distinctive building facades along the north side of Clay Street (between Waverly Place and Dupont Street) perhaps at the height of the glory. With the paint scheme of the buildings’ facades now lost to memory, one can only speculate about how Arnold Genthe’s “street of painted balconies” dominated this block of Clay Street. Wulzen’s images were particularly clear, and the details of the buildings as seen from across the street and angled toward the downward slope of the street in the easterly direction captured Chinatown on a sunny day. At the far right of the frame, the trees at Portsmouth Square park can be seen.

The writing on the lanterns suspended at the ground floor level read 悦香酒樓 or Yoot Heung Low (restaurant) and the second floor signage seen in earlier photos remains, i.e., 茶居 (canto: “cha geui”) or tea house. The top floor was usually reserved for the merchant elite and their guests.

“Chinatown – Clay Street toward Dupont Street, August 24, 1901.” Photograph by D. H. Wulzen from the D. H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (Sfp 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library. The long vertical sign at the left vertical frame of the restaurant’s façade (the last character of which is blocked by a bundle of materials), advertises 包辩酒席占点心餅食俱 (“bow bun jau jik dim sum behng sihk geuih” etc.) or 包辦酒席 can host banquet; 點心餅食 dim sum bakery; 俱 both.

Wulzen’s photos of the north side of Clay Street in 1901 indicated that little had changed in terms of the land use for this 800-block of Clay Street during the preceding two decades. In July 1885, the city’s public health map had recorded, in descending order from the northeast corner of Waverly Place and down to Dupont Street as follows: street number 814 (general merchandise), 812 (residential entrance), 810 (restaurant), 808 (barber shop), and 806 (general store). The address for the building at the northwest corner of Clay and Dupont served as a general merchandise store with its entrance located around the corner at 801 Dupont St.

“Returning Home, Chinatown, San Francisco” or “After School, Chinatown, San Francisco” c. 1900 -1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. In that era, children often roamed unaccompanied around the neighborhood. Again, the shuttered restaurant storefront indicates that the building was closed for a holiday, probably the New Year. The child, accompanied by a father, holds the holiday treat of a balloon, and they follow the pair of children in the center of the photo. The photographer Genthe stood in practically the same place on Clay Street, looking toward 810 Clay St., and from where he took his other photograph titled “A Family from the Consulate.”

“Chinese Restaurant” c. 1902. Illustration by J.T. McCutcheon for the travelogue “To California and Back” by C.A. Higgins. The building elevation of the Yoot Hong Low restaurant was included without identification among drawings inspired by contemporary photographs.

A view east along the north side of Clay Street between Waverly Place and Dupont Street, c. 1903. Photograph William Baylis from “A trip to California :

[a series of fine western pictures from original photographs in Colorado, Utah, California, the Pacific coast, Yellowstone national park]” from the collection of the Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Clay near Dupont Street, c. 1905. The view east on the north side of Clay between Waverly Place and Dupont Street. The Clay Street cable tracks appear in the foreground. Colorized photograph by an unknown photographer (courtesy of a private collector).