#'but its boring' have you considered working with his kindness instead of mischaracterizing his whole point

Text

dont like the trope of using characters who love and care and try their best by making them evil just for character progression

#im literally never gonna shut up about it#dream is like one of the only characters in utmv we have that represent genuine love and u mistreat him like this.........#dream sans#kia doodles shit#'but its boring' have you considered working with his kindness instead of mischaracterizing his whole point

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a theory: the Pan-Africanists who hate #ADOS don’t hate #ADOS because of the latter people’s actual politics. Pan-Africanists hate #ADOS because the people who are involved in that movement are pointing out something that no one else will: that Pan-Africanism in 2021 feels like a response to a question that basically no one really even asks anymore. That for all of their grand pronouncements—the epic and almost mythic sense of their project’s historical certainty—it’s becoming harder and harder to ignore how Pan-Africanism today just sort of feels in a lot of ways like the soggy nub of a joint being passed around at a dwindling party.

Think about it. Does the strangely visceral opinion about #ADOS held and oft expressed by Pan-Africanists really spring from the former’s politics? Yeah? Really? Well, what is it about the #ADOS political agenda specifically that they so hate? Is it that they would like the U.S. government to continue holding onto the trillions of dollars that it owes these people? Is it that they approve of chemical plants and refineries and waste dumps being strewn throughout black American communities in such a way that basically ensures those residents—simply by going outside and inhaling oxygen—contract what are 100% lethal diseases?

Or is it more likely that these people feel somewhere deep down that ADOS are like some kind of apparently lower form of oppressed subjects? And that, as such, they simply aren’t entitled to (or even capable of?) determining their own fate. Is it that they feel ADOS are being insubordinate and unmanageable and refractory and childish? Is it that in their assertion of agency and in their unsparing critique of the international movement that has patently failed them ADOS are hurting the feelings of many people who are—let’s be honest—way too emotionally overinvested in what’s mostly become just a quaint area of scholarship in our universities’ Africana Studies departments?

Just a theory! But doesn’t that seem like maybe a more honest answer?

Maybe those Pan-Africanists just hate that #ADOS has been quite successful in its reparations advocacy despite the movement’s refusal to conform to Pan-Africanist orthodoxy. And maybe it’s that these Pan Africanists have a faint notion that wounded pride isn’t exactly a sophisticated reason to critique #ADOS, so they instead invent some bullshit political pretext about how #ADOS’s advocacy is ‘ahistorical’ or totally reactionary or that those in the movement are corrupted by a strain of American exceptionalism or whatever.

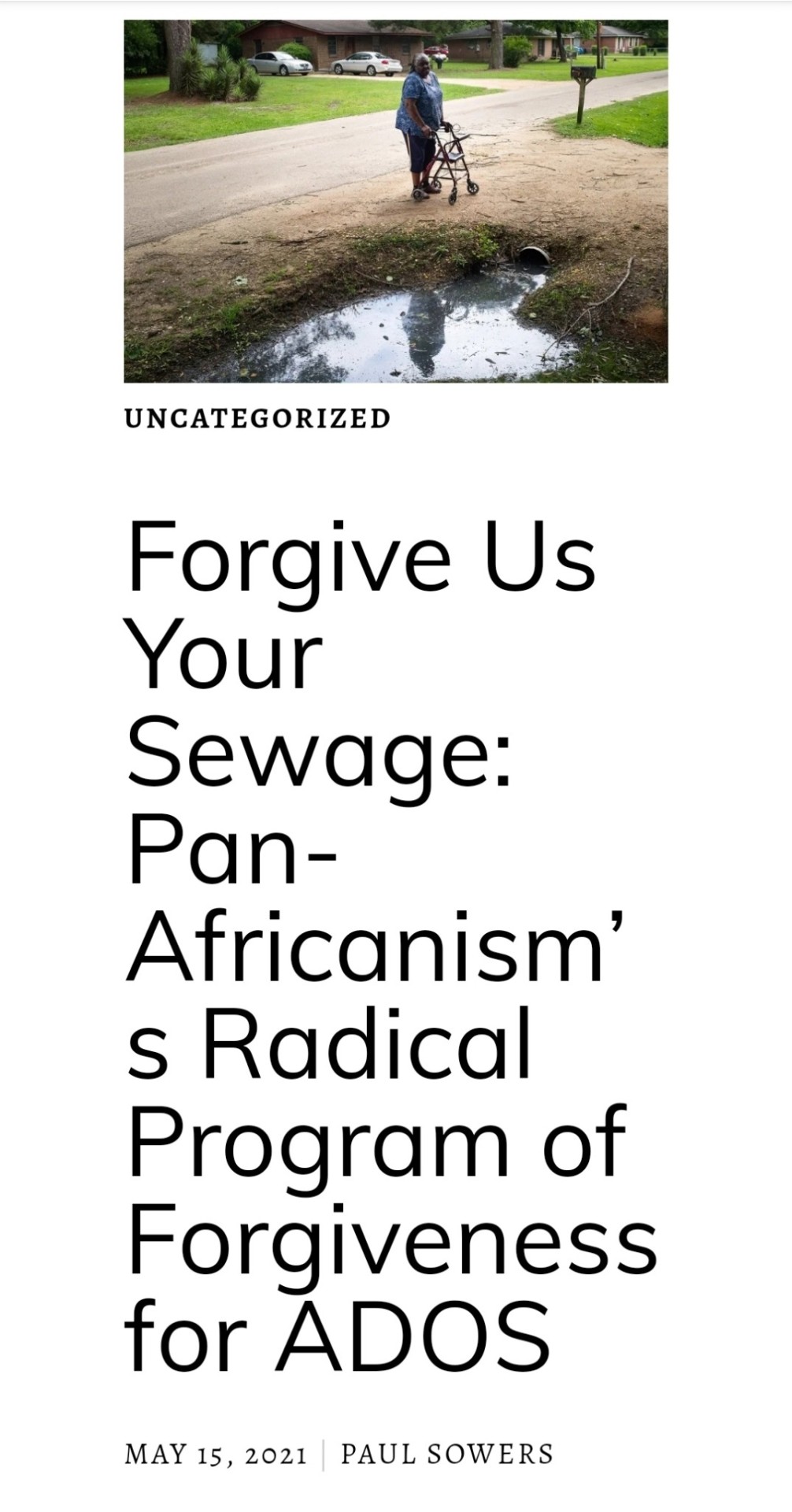

That, anyway, is the basic defensive crouch position from which Broderick Dunlap writes his recent article, “A Dose of Reality for the ADOS Movement”. Adhering tightly to what is now the standard formula for a Pan-Africanist-Critique-of-the-#ADOS-Movement think piece, Dunlap’s essay is deeply fucking boring, stiff, and backward-gazing. It is obsessed with identifying earlier modalities and pointing out the completely obvious fact that #ADOS’s approach does not correspond with them (which, given the failure of those forms of identity and resistance to offer a bulwark against something as basic as inadequate sewage treatment, let alone unify an entire continent, well, duh!). But mostly Dunlap’s essay just aims to persuade the reader that reparations isn’t about money; that the real and most vital question that black people in America need to consider (black people who are forced to live under regularly occurring boil water advisories, mind you!)—is: “what will it take for Black folks to forgive the United States?”

It is true that, in the #ADOS political literature, this inquiry into the capacity of black people to forgive their victimizer is never raised. It also seems true that it is difficult to imagine a less radical and more insulting position than that, but, anyway, I digress. Thirdly, the suggestion that the only thing that #ADOS is concerned about is a simple transaction of overdue funds—after which they just sort of dust off their hands and raise a glass to victory while beginning to contemplate their new investment portfolios—is totally absurd, very easily disproven, and yet another example of the strong tendency among Pan-Africanists to feel that it is their right to define the #ADOS movement however they like.

But if the demand for monetary compensation to be paid to their group is what makes #ADOS a supposedly purely avaricious movement—if that is why they must be vilified and opposed and viewed as a blasphemous and debauched form of a black liberation movement—then what is one to make of similar demands for material redress made throughout the diaspora directly to that nation’s former colonizer? Here’s one such example involving Barbados’s demand for the United Kingdom to pay it reparations. Or when Hilary Beckles, chairman of CARICOM’s reparations commission explains that the organization of Caribbean member states is “focusing [our reparations claim] on Britain because Britain…made the most money out of slavery and the slave trade – they got the lion’s share,” where is the prolonged outrage from the Pan-Africanists who would otherwise decry the omission of other diasporic groups from this one-nation-in-the-crosshairs look at who owes who what? Why don’t the people making the argument for those reparations get accused of merely wanting “crumbs��� from the old imperialistic British pie or whatever? Again, we are asked to believe that the Pan-Africanist antipathy toward #ADOS is rooted in a fundamental political disagreement, or like some inviolable set of internationalistic beliefs. But when demands that are analogous to those of #ADOS receive effectively none of the hostility and outright disdain that the #ADOS’s demand for reparations appears to singularly attract from the rest of the diaspora, it sure becomes hard not to see a more cynical motivation at the core of the their ‘critique’ of the movement’s political aims.

Here’s what I think: I think that the refrain of reparations not being about money is a slogan that is 100% designed to sheepdog would-be serious reparations advocates into supporting business as usual forever here in America. I think once you say something like that you have been brought right into the Democratic Party’s orbit and the DNC will make short work of turning your little proclamation of righteousness and purity or whatever the fuck it is into a feel-good campaign of money-free ‘justice.’ I think the accusation that monetary reparations for ADOS are viewed by that group not as the seeds to self-determination but rather as the harvest itself is a lie concieved in malice and spite—that it is a mischaracterization that strives to bastardize a project that has only ever argued the need for a significant restructuring of the (highly group-specific!) maldistribution of wealth in America before their group could ever meaningfully participate in any kind of internationalism. But what I really can’t account for though is why ADOS saying that activates some serious lizard brain shit in a whole lot of people. Or why those people apparently feel the need to gussy up that brute emotional response in some bogus political principle that they can’t really criticize without hypocrisy: it is OK for CARICOM to explicitly exclude ADOS from their reparations claim against imperial powers (and merely refer them to another organization trying to make additional pecuniary arrangements for Caribbeans), but it is a cause for moral outrage when #ADOS tries to take their group’s case to the U.S. government? I don’t know. That sort of unevenness of application strikes me as people who are motivated way less by actual ideas and more by the people themselves who are doing what they’re doing. And what are ADOS even doing that’s so totally unconscionable anyway? Turning to one another and becoming passionately invested in their shared experience instead of performing a committment to something that is no longer really a relevant force in the world but which will get them meaningless approval by lots of strangers? Again, I don’t know. It just seems like a lot of the time that what governs opinion about #ADOS involves a lot more high school lunchroom behavior than what those people would like us to believe.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beccaland reads and responds to an article about Doctor Who that she really should have known better than to have read in the first place

You know how you KNOW you should never read the comments sections, but sometimes you just can’t help yourself? That’s usually how I feel about reading articles about Doctor Who during the past few years, except from a handful of trusted sources. Yet there I was this morning, checking my regular email from Tor.com, and out of a slightly-morbid curiosity, I found myself reading “How It Feels to Want to Watch Doctor Who Again” by Alex Brown.

Partly, I really am interested in the fans who are getting interested in Doctor Who again. They left for a lot of reasons, and really you can’t begrudge anyone’s waning interest in a TV show. And it would be far, far more silly to begrudge them regaining interest! I’m excited for the awesome changes that are coming on October 7th, too. And I am fully aware that not every era is every fan’s cup of tea. On the other hand, I also know that I’m frequently irritated by the shallow criticism levelled in order to “justify” some fans’ disaffection. So there I was. Reading an article I knew very well was probably going to annoy me, like a masochist.

And just because I feel like it, I’m going to quote a bunch of it and offer my own commentary. I’m going to be as fair as I can, noting where I think a given critique is valid, where I think it’s valid but still disagree, and where I think it’s the same old tired, inaccurate nonsense.

Here we go:

“I miss Doctor Who.”

ME TOO!

“There was a time when I watched it fervently, reverently, passionately. It was something I put on when I was stressed or overwhelmed or needed to be reminded of the good things in life. The relationship wasn’t perfect, but it was powerful and affirming.”

Yeah, I do that too, but I never really stopped.

“Until suddenly it wasn’t.”

I mean, sure. Doctor Who did something on a purely personal and emotional level for the author, and then it stopped. That’s totally fair.

This actually happened to me with the novels in the ‘90s–they just weren’t doing enough for me imaginatively or emotionally anymore to justify the challenge of finding them and the expense of buying them. It happens. (I still wanted Doctor Who in my life though, so I rewatched my VHS tapes instead, until they had degraded in quality to the point where that wasn’t very fun either.)

“The show twisted into something unrecognizable and unpleasant. And so I abandoned Doctor Who just as it had abandoned me.”

The really negatively loaded language here bugs me a lot, but this article is a personal fan narrative more than it is a review, and it’s impossible to refute a subjective response. Clearly, it’s true that Alex Brown and the show were no longer on the same wavelength. So, fair enough.

“If you asked me in 2016 if I would ever watch Doctor Who again, I probably would’ve shaken my head and sighed. The chances of the show making the kind of changes necessary to pull me back seemed slim to none. But here we are, fall 2018, and I am so excited about the Season 11 premiere that I can barely stand it.”

I’m really happy about everyone coming back. I share this excitement!

[I’m omitting a couple of paragraphs here where Brown describes more of what Doctor Who meant to her when she first encountered the show during an obviously extremely difficult time in her life. It’s really moving, and I find it relatable in some ways.]

“With the takeover by Steven Moffat in 2010, my relationship with the Doctor shifted dramatically. As much as I loved Doctor Who, I wasn’t blinkered to its myriad problems.”

See, my issue with this is simply that it implies that people like me ARE “blinkered by its myriad problems.” We’re not. But sometimes we disagree about what those problems are, or where the blame (and praise) for those problems (and their amelioration) properly lies. Hence this post.

“Trouble was, the annoying but tolerable issues were magnified into something unbearable by Moffat’s numerous faults as showrunner. Under Moffat, seasons went from episodic romps loosely knitted together by repeating themes—think “Bad Wolf” Easter eggs throughout the first season—to Lost-style mystery box seasons bogged down in an increasingly convoluted and grimdark mythology.”

I think it’s fair to say that the series 6 arc in particular was much heavier than previously attempted by the show, and this was a turnoff for some viewers. Personally, I liked it a lot conceptually, but I acknowledge that it could have been better executed. It’s also not representative of Moffat’s whole era; he experimented a lot with structure. That in itself was probably frustrating to some viewers–again, I liked it a lot, but that’s neither here nor there.

However, calling the Moffat era “grimdark” is frankly bizarre. It seems to confuse a shift in LIGHTING with a shift in TONE. The Moffat era’s TONE was, if anything, substantially more hopepunk than the RTD era (to say nothing of Torchwood, which Brown also professes to adore).

“River Song, Cybermen, Daleks, and the Master work best when used sparingly,”

Yeah, I agree.

“but Moffat dragged them out of the toy box so often that they lost their appeal.”

A criticism that (aside from River, for whom YMMV) applies equally to the RTD era.

“Even the Doctor suffered from too much focus. Doctor Who is a show that flourishes when it cares more about the people the Doctor helps than the Doctor. The Doctor is much more interesting as a character who drops into other people’s stories than when everyone else exists only to serve the Doctor’s narrative.”

This is a matter of taste, and on that level cannot be refuted.

But I’m not actually sure it’s true that the stories in the Moffat era focused more on the Doctor than was the case in previous eras. It didn’t seem that way to me. I suppose one could develop some way of objectively evaluating the validity of that premise, but I’m not going to go to that much trouble.

“Worse, women went from equals with their own vibrant lives to codependent followers.”

This is not merely a matter of personal taste. It is an assertion about content of the sort which could hypothetically be supported by evidence. If it were true. And it is literally the opposite of true. It’s a gross mischaracterization of the Moffat era companions, and moreover ignores the sometimes-problematic characterizations of the RTD era companions. I’m skipping the rest of that paragraph, which merely rehashes worn-out, shallow readings of Amy and Clara’s characters. I have nothing to say about those arguments that I haven’t said elsewhere before.

“[Moffat’s] seeming disdain for how fans interpreted the series,”

Showrunners SHOULD disdain how fans interpret their work. Or, more accurately, they should ignore it. Since fans are a motley bunch, the alternative would be a total lack of creative vision, either deeply bland or utterly fractured.

“for critiques of his own biases and bigotries,”

In reality, Steven Moffat demonstrated a remarkable openness to critiques of his biases and made steady progress in addressing them both in front of the camera and behind the scenes.

“and for the depth the show was capable of became a virus that infected everything.”

From where I sit, Doctor Who demonstrated far more depth during the Moffat era than during the RTD era (and some of the deepest scripts in RTD’s era were written by Moffat and according to RTD, barely touched by his editorial influence). I’m willing to consider the possibility that the RTD era displayed depths that I failed to perceive, but given the number of times I’ve rewatched it and the fact that I study texts for a living, I have to say I think that’s a long shot. I would welcome a persuasive analysis of the depths of the RTD era.

“I have never been one to shy away from dropping shows that I no longer like, but I held onto Doctor Who longer than I should have. I finally tapped out after the frustrating penultimate episode of Season 6, “The Wedding of River Song.” Reductive, repetitive, and boring, the episode encapsulated everything I couldn’t stand about Moffat’s storytelling.”

OK, Brown has got a point there. I love TWORS for purely personal reasons (it was just FUN, in the same way that the more crazy-ambitious failures often are in Doctor Who), but I’m under no illusions about its quality. In addition to being “reductive [and] repetitive” that episode was also rushed and full of holes. I didn’t find it boring, but that’s a subjective thing.

It’s a bit weird though that Brown claims to have quit watching Doctor Who at the end of series 6, since earlier she critiqued both Clara and Moffat’s “over"use of Missy, both of whom post-date Brown’s purported exit. Hmm. Seems like (as is not uncommon, in my experience) people who dislike Moffat base a lot of their dislike on mere hearsay.

"Although Moffat drove me away from Doctor Who, other factors kept me from coming back. A not insignificant chunk of my exhaustion came from the frustratingly limited diversity and the frequently poor treatment of characters of color—see Martha and Bill, plus the weirdness around the few major interracial relationships.”

OK, this is approximately half fair. There WAS a frustrating lack of diversity which continued well into Moffat’s era. Martha and her weird marriage to Mickey are RTD’s doing entirely. And the author claims not to have ever seen series 10, so she’s hardly in a place to evaluate Bill’s treatment (which, for the record, seemed pretty great to me–vastly better than in any previous era, anyway, though there’s no doubt that there is still room for improvement).

“Prior to Season 11 there had never been an Asian or South Asian companion despite the fact that people of South Asian ancestry make up nearly 7% of the population of England and Wales, according to the most recent census. Islam is the second largest religion in the UK, yet Muslims are also largely absent from the show, and certainly from the role of companion.”

This is a totally fair criticism.

“Moffat said it was hard to cast diversely without impinging on historical accuracy,”

Gonna want a citation for that one; I admit it’s possible he said something like that at some point but I feel like I would remember if he had.

“a notion that is patently false and wholly ignorant of actual history.”

A point which Sarah Dollard makes in the series 10 episode “Thin Ice,” with the enthusiastic approval of Moffat himself.

“To be fair, Moffat also admitted this claim was nonsense and rooted in a white-centric view of history and acknowledged that the show needed to do better…then made absolutely no changes.”

Thanks for being fair…almost. In fact he made substantial changes during his tenure, though most happened after Alex Brown quit paying attention. Seems to me that if you’re going to write an article for a blog affiliated with a major SF publisher, you might actually want to check your facts rather than relying on information that’s several years out of date (if it was ever true).

“And don’t even get me started on frequent Moffat collaborator and Who writer Mark Gatiss who infamously whined about diversity initiatives ruining historical accuracy because they cast a Black man as a soldier on an episode about Queen Victoria’s army battling Ice Warriors on Mars.”

Yeah, this I do remember. Ew, Gatiss! What were you thinking?

“Not to mention Moffat’s asinine declarations that we couldn’t have a woman Doctor becausehe 'didn’t feel enough people wanted it’ and 'This isn’t a show exclusively for progressive liberals; this is also for people who voted Brexit.’”

This is also the man who wrote the first-ever gender-changing regeneration (of the Doctor, no less!) in his comedy special, “The Curse of the Fatal Death,” the first female incarnation of a previously male Time Lord (Missy, who turned out to be incredibly popular), and the first official, non-comedy, on-screen gender-changing regeneration scene (the General, in Hell Bent), thus paving the way for even many of those non-liberal, Brexit-voting audiences to accept a female Doctor, and making it virtually impossible for the BBC not to do it without looking like total assholes (though by that point they were totally on board and needed to further persuasion).

But sure, go ahead and cherry-pick a couple of real-but-not-representative Moffat quotes to perpetuate your misogynistic Moffat pseudo-narrative.

[Cutting the rest of that paragraph because it adds nothing to the critique]

“Why can’t we have a trans or disabled companion? Why can’t the Doctor be a queer woman of color?”

These are totally legitimate questions, and we should keep asking them.

“Do you know what it’s like to be told by someone in a position of power that you don’t belong here? That you are an aberration, a glitch in the matrix, that including you would be so inaccurate that it would collapse the narrative structure of a fictional television show that features a frakking alien traveling through time in a police box?”

Yes. I do.

And when you dismissed Amy and Clara as mere sexist stereotypes, mere codependent hangers-on of the Doctor, you re-inflict that wound on me and many other fans, because you’ve been granted a position of power, a platform in the blog of a major international SF publisher.

“Hearing that message all the time from pop culture is hard enough, but to get it from my favorite show was heartbreaking.”

I feel ya, Alex Brown. This needs to continue to be addressed.

But I’ll also remind readers that the Moffat era, despite its still-too-limited representation, gave us more disability representation than any other era of the show up to that point.

“Cut to the Jodie Whittaker announcement in July, 2017. For the first time in years, I watched the Christmas special—live, no less. To give credit where credit is due, Moffat’s swan song exceeded my (very low) expectations and Peter Capaldi was as excellent as I hoped he’d be. Whittaker had almost no screen time, but what she did get left me with a smile a mile wide.

"On top of her pitch-perfect casting, Thirteen will also be joined by three new companions, one a Black man and another a woman of Indian descent. Plus, the Season 11 writers’ room has added a Black woman, white woman, and a man of Indian descent. Several women will also be directing. New showrunner Chris Chibnall proclaimed that the renovated show will tell 'stories that resonate with the world we’re living in now,’ and will 'be the most accessible, inclusive, diverse season’ ever produced.

"These changes go beyond tokenism and into real diversity work. The show isn’t just sticking a woman in the titular role and patting themselves on the back. Diversity can’t just be about quotas. It must be about inclusion and representation in front of and behind the camera. Marginalized people need to be able to tell our own stories and speak directly to our communities. The majority already gets to do that, and now that conversation needs to happen across the board. The show still has a lot of work to do, both in terms of undoing the status quo of harmful tropes and in laying strong groundwork for later casts and crews. Yet, somewhat surprisingly, I feel hopeful for the show’s future.”

I totally agree with these three paragraphs (except I had high expectations of TUAT, which were also exceeded). In fact these paragraphs are a big part of why I felt like this article was worth sharing. I just couldn’t do it without significant reservation.

“And isn’t hope what the show is really all about? Doctor Who is a story about the hope for a better tomorrow, faith in your companions, and trust that you’re doing the right thing. It’s about a hero using their immense powers responsibly and in order to benefit those who need it the most. The Doctor creates space for the marginalized to stand up and speak out, to fight for their rights against those who would silence or sideline them.”

I’m not totally sure that that’s ever really been true before, but it’s an ongoing aspiration that the show keeps moving closer to.

“For too long, that ideal was lost to puzzle boxes, bloated mythology, and trope-y characters”

No it wasn’t. See above.

“but with the appearance of each new Thirteenth Doctor trailer, my hope grows a little more.

"It’s not often that you find your way back to something you loved and lost. At first, Doctor Who was a touchstone during my trials and hardships. Then it became a cornerstone in the foundation of the new life I was building. For a long time I left it encased in a wall, hidden in the basement of my subconscious, untouched and unwanted. Yet here I stand, sledgehammer in hand, putting a hole in that wall. I have set free my love of Doctor Who as Jodie Whittaker cheers me on. October 7 can’t come soon enough.”

This sentiment is really lovely. Welcome back, Alex Brown, and every other fan returning to Doctor Who after an absence of any length and for any reason. It’s shaping up to be a great new era.

Please remember, though, when talking to other fans, that other eras meant as much to some of them as this one means to you, and for similar reasons.

To those who are leaving because of toxic discourse about previous eras making them feel like their presence isn’t welcome and/or participating in fandom right now will only cause them pain: I’m going to miss you. I hope your DVDs and Big Finish and stuff continue to bring you joy. I hope you’ll come back again when it’s safe to do so.

To those who are leaving because they don’t like the idea of a female Doctor and/or two POC companions: BYE BYE! To be honest, nobody will miss you, but nevertheless I hope that eventually you realize how silly and harmful your biases are. When you do, I hope you’ll come back to Doctor Who. And you’ll be welcome.

30 notes

·

View notes