#餝屋

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 4 (8): Concerning the Number of Objects Displayed in the Ō-doko [大床], on the Shoin-doko [書院床], and on the Chigai-dana [違棚].

8) In the ō-doko [大床]¹, the shoin-doko [書院床]², and the chigai-dana [違棚], taking the objects [displayed] in all of these together, the total count should be [an] odd [number]³.

In Sōeki's⁴ nanatsu-gumi kyōka [七つ組狂歌], also, [we have to understand that “nanatsu” means] not that [the number of objects] should be limited to seven⁵, but that the number should be odd -- this is what has been taught⁶.

_________________________

◎ This is another passage that, at least partially, was clearly not included in Jōō's original set of notes -- since it refers to a pair of poems* purportedly by Rikyū.

Most likely, Jōō's entry was limited to the statement that makes up the first paragraph, while the rest appears to have been added by another hand†, many decades later.

__________

*Which may have been inserted into the Shū-un-an documents during the early Edo period.

†The individuals who modified the collection of unrelated documents that Tachibana Jitsuzan later amalgamated into Nampō Roku -- prior to its coming into his hands -- always did so to further one or another agenda (the primary purpose of the agents of the bakufu seems to have been to encourage the use of more and more utensils, and, secondarily, to validate Kanamori Sōwa's version of chanoyu history; while those people acting on behalf of the Sen family sought to align the teachings contained in these documents with those embraced by that family -- in so far as that could be done interstitially and without actually changing the original text).

¹Ō-doko, shoin-doko, chigai-dana [大床、書院床、違棚].

Ō-doko [大床], meaning “large toko,” originally referred to the built-in version of the oshi-ita (adjoining the jō-dan [上段], the raised floor on which noble personages were seated, and sometimes acting as a sort of background to them), though in the sixteenth century (particularly in machi-shū tearooms, where it was usual for no one to be seated on the jō-dan) it was sometimes conflated with the jō-dan itself (and this remains the case today, where the tokonoma functions as both an alcove in which art objects are displayed, and as a jō-dan).

Shoin-doko [書院床] refers to the dashi-fuzukue -- the built-in writing desk.

And chigai-dana [違棚] are the pair of staggered shelves, originally located on one side of the dashi-fuzukue, on which papers and books were placed (when the shoin was used as a private study).

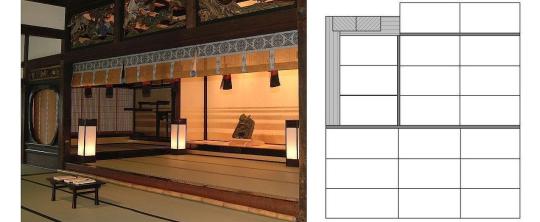

These elements are seen in the photo, above, which shows what is termed the jō-jō-dan [上々段] (a super-elevated floor section used by someone like the Emperor, or a retired Emperor -- this building was originally built as an imperial residence) on the left. This area features a dashi-fuzukue (on the far side of a person seated on the jō-jō-dan, when facing out into the rest of the room as during an audience) adjoined by a chigai-dana (to the right of the writing desk), with the ō-doko located on the jō-dan, one level below.

This kind of arrangement is also seen in the Dōjin-sai [同仁齋] (above) -- though this smaller room completely lacks an ō-doko†.

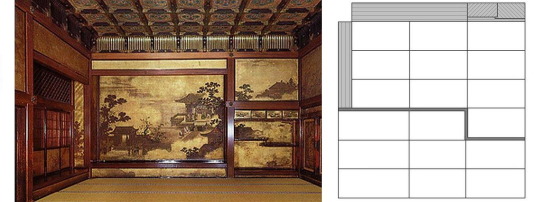

The shoin, however, continued to evolve (as shown in the second photo, above), with the biggest step being the interpositioning of the ō-doko between the tsuke-shoin (on the left) and the chigai-dana (on the right), creating a series of spaces intended primarily for display (rather than for use, as a study).

²Tori-awasete mono-kazu han nari [取合せて物數半也].

While tea people usually use the word tori-awase [取り合わせ] to mean the selection process involved in assembling a set of utensils for a given temae (or gathering), tori-awase more generally means an assortment, variety. Here it refers to the various utensils* (mono-kazu [物数]) that make up the collection of objects displayed in the various locations around the shoin†.

___________

*Perhaps “numerous objects” would be a more literal rendering of mono-kazu -- though the English numerous tends to suggest a much larger number than what is inherent in the Japanese.

†Note that in this entry the focus is exclusively on the objects displayed in the toko, on the dashi-fuzukue, and on the chigai-dana. The daisu, and any utensils arranged on it, are not being considered here (for which reason, the allusion to Rikyū’s kyōka -- see the next footnote -- as a guide to the arrangement of these several venues, is odd, since he was referring to the gathering as a whole, not just the display areas.)

³Nanatsu-gumi kyōka [七つ組狂歌].

This refers to the two kyōka [狂歌] (“crazy poems”)*, that may be found as entry 56† in Book Five of the Nampō Roku:

(1) chigai-dana ・ ō-doko shoin ・ wabi-zashiki

moto ha daisu no itsutsu-kane nari

[違棚・大床書院・ワビ座シキ

モトハ臺子ノ五ツカネナリ].

(2) ko-zashiki mo sen-jō-jiki no mono-kazu no

moto ha daisu no nanatsu-gumi nari

[小座鋪モ千疊敷ノ物數ノ

モトハ臺子ノ七ツ組ナリ]‡.

Which mean:

(1) “the chigai-dana, the ō-doko [and its] shoin [書院]**, [and] the wabi-zashiki [ワビ座敷]††: the basis [governing the arrangement of objects in all of these locations] is [always] the five-kane of the daisu‡‡;” and,

(2) “in the small room, as also in a room of a thousand mats, with respect to the number of objects, the basis is the nanatsu-gumi*** of the daisu.”

___________

*While kyō [狂] literally means “possessed of a mental abnormality;” fiendish; insane -- and, not infrequently, poems included in this category might strike the reader as being unhinged -- the usual use of the designation refers to poems with unusual or anomalous diction.

†Unfortunately, this entry (which is found between the section of the book dedicated to the large shin-daisu, and that which illustrates the use of the small shin-daisu, in the inakama setting, associated with Jōō’s seven-kane system) is not certified (by a note, indicating Rikyū’s authentification of its accuracy), like all of the other entries in Book Five. Indeed, the poems appear to have been inserted between the pages of the original manuscript (since the original manuscript seems to have been made into a notebook, this was easily enough done by splitting a double-page open by cutting through the fold on the outer edge of the page, thus giving two blank pages on which virtually anything could be added). This, coupled with the use of an expression uncharacteristic of Rikyū (but common enough among the writings of the machi-shū who were gathered around Sōtan -- so common that it can be used to identify the writings of the members of this group), strongly suggests that the poems on which this argument turns were, themselves, spurious.

That said, both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Sensho quote the poems in their commentaries, suggesting that this was a long-established part of the body of teachings that were handed down by the scholars affiliated with the Enkaku-ji.

‡Ko-zashiki mo sen-jō-jiki no mono-kazu no, moto ha daisu no nanatsu-gumi nari [小座鋪モ千疊敷ノ物數ノ、モトハ臺子ノ七ツ組ナリ].

Ko-zashiki [小座鋪] means ko-zashiki [小座敷]. This is another usage, not found in Rikyū’s writings, that was rather popular among the machi-shū writers of the early Edo period. This particular kanji, shiki [鋪], means a shop or store (hence, apparently, the machi-shū usage -- since most of them were of the merchant class) -- though, when used with that meaning, the kanji is usually read ho [ほ] (and this is so when found in the name of a business). When it is pronounced shiki, the word means a mine-shaft or tunnel. (Again, I have noticed this kind of thing to be another characteristic of the machi-shū tea writings from the early Edo period -- though whether it was done through force of habit, or so as to make their writings more mysterious and inaccessible to the “uninitiated,” is something I cannot resolve.)

The expression ko-zashiki [小座鋪] was used when referring to what Rikyū himself usually called a ko-yashiki [小屋敷] -- meaning the small room, when erected as an independent, free-standing construction, separated from the main house by a garden of varying description.

**Shoin [書院], here, specifically refers to the built-in writing desk. What the author of Book Four usually calls the shoin-doko [書院床].

††Wabi-zashiki [ワビ座敷], literally “wabi sitting-room,” in this poem means the wabi small room.

In other words, the poem is addressing the way to arrange the utensils in all of the possible settings in which chanoyu may be staged.

Rikyū, in his writings, is always concerned about chanoyu. He never discusses the arrangement of settings that will not be used for drinking tea.

‡‡Moto ha daisu no itsutsu-kane nari [モトハ臺子ノ五ツカネナリ].

Moto [本] means origin, source, basis, foundation, causative principal, and so forth The principal which governs the arrangement of objects -- whether in the toko, on the dashi-fuzukue or chigai-dana, in the shoin or in the wabi small room -- is the system of five kane derived from the superimposition of the shiki-shi [敷き紙] on the daisu.

***Nanatsu-gumi [七ツ組].

This is the expression that gives away the source of this part of the entry, since nanatsu-gumi was never used by Rikyū (or anyone who had been initiated into the secret teachings of gokushin no chanoyu).

According to Rikyū, kumi [組] is to be used when referring to objects displayed on the ten-ita of the daisu (probably because such objects -- the chawan and the chaire principally -- were, originally, always “collected together” on a tray, this being what kumi means), while kazari [餝 = 飾] (decorate or display) is used with reference to the things on the ji-ita (the term nanatsu-kazari specifically means that the seven utensils -- kama, furo, mizusashi, hishaku, shaku-tate, koboshi, and futaoki -- are arranged on the ji-ita). Nanatsu-kazari futatsu-gumi [七ツ餝二ツ組], then is a description of the most orthodox of the gokushin arrangements -- the full nanatsu-kazari below, coupled with the dai-temmoku and chaire arranged together on a naga-bon (with the naga-bon acting as a chaire-bon during the temae).

The machi-shū, however, unaware of the secret conventions of this nomenclature, combined the two into nanatsu-gumi [七ツ組], by which they meant the seven utensils that were collected together on the daisu: (1) kama-furo, (2) mizusashi, (3) shaku-tate (naturally containing the hishaku), (4) koboshi, and (5) futaoki (on the ji-ita); together with the (6) dai-temmoku and (7) chaire (perhaps on a naga-bon, perhaps not), on the ten-ita. Any document that contains the expression nanatsu-gumi is of machi-shū origin, and this expression indicates that its author had not been initiated into the conventions of gokushin no chanoyu. The arrangements could be observed by anyone who participated in a chakai hosted by an initiate, and so replicated by anyone who had access to a similar set of utensils; but the minute details of the arrangement, and the special language associated with its conventions, were only known to the cognoscenti.

As for what it means (in light of the above), it seems that the author of the poem (whomever he was) is saying that the principal on which the decoration of the chigai-dana, the ō-doko and its shoin, as well as the small room is determined, is the deliberate association of the different objects with their respective kane -- and how these relationships are delineated (whether the object is placed squarely on its kane, overlaps the kane by one-third, or is placed in between the kane and thus counted as chō [調]). The poem certainly does not suggest that the number of objects should total -- and not exceed -- seven.

⁴Sōeki [宗易].

This was the name that Rikyū used during his professional career as a tea master.

⁵Nanatsu ni kagirazu [七つにかぎらず].

Kagiru [限る] means to restrict or limit. Kagirazu [限らず] is the negative form -- to not restrict, not limit; hence, not only (seven objects).

Precisely how the number “seven” (referring to the total number of objects that can be displayed in the ō-doko, shoin-doko, and chigai-dana) came to be derived from the above-quoted poems is -- at least to me -- a mystery. In fact, this all seems to be a garbling* of several different lines of thought, including the section of the Nambō-ate no densho [南坊宛の傳書] entitled kakoi no toko ni nanatsu-kazari aru-koto [カコイノ床ニ七飾餝有事]†, and the machi-shū idea of nanatsu-gumi that was explained in sub-note “††” under footnote 3.

___________

*Though whether this was a misunderstanding committed by Tachibana Jitsuzan, or by the person responsible for adding this sentence to the entry, is not clear (though I would tend to suspect the latter, for the reasons that will be discussed below).

Jitsuzan is known to have read the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho [利休茶湯書] -- indeed, it was this that opened his eyes to the continuing existence of Rikyū’s writings, and so inspired him to make a detour to visit the Nanshū-ji in Sakai on his way from Kyōto to Edo, so that he could look through the collection of documents archived in the wooden chest in the Shū-un-an for material that had not been included in the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho. This makes it much less likely that he would be guilty of this kind of misunderstanding (unless his review of the contents of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho was perfunctory), since that text makes it clear that the expression nanatsu-kazari refers to seven different arrangements for the kakoi-toko [圍い床] (which means the simple toko found in the small room), rather than an arrangement of seven objects.

Nanatsu-kazari, when applied to the shin-daisu, refers to the seven objects -- kama, furo, mizusashi, hishaku, shaku-tate, koboshi, and futaoki -- arranged on the ji-ita of that daisu. Meanwhile, the word kumi [組] (which means something like “gathered together”) was used by Rikyū (and proponents of the orthodox tradition) only when referring to the group of objects displayed on the ten-ita of the daisu (this usage was a secret matter, the purpose of which was apparently to distinguish between people who had been initiated into the gokushin teachings, and those who had not). The machi-shū, who lacked access to the gokushin tradition, typically confused the two terms -- and this is precisely the situation seen in this entry.

†Literally, “there is the case where there are seven arrangements for the toko in the kakoi.”

Kakoi [圍い] means an enclosure (in which chanoyu was performed), usually made by screening off a three-mat area at one end of an eight-mat reception room. At this point in time (mid-sixteenth century), the preferred style of temae utilized the large iron furo and abbreviated set of kaigu (usually mizusashi and koboshi, or mizusashi and futaoki), arranged together on a naga-ita. Later this expression seems to have been used to refer to the small room (perhaps including free-standing constructions) -- as here.

Rikyū’s Nambō-ate no densho is dated 1574, and is the earliest of his writings to survive. A copy of this document (which remained in the Shū-un-an at least until the late 1660s) was taken by Furuta Sōshitsu in 1595, and copies of this version circulated privately until the publication of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho, in 1680. There are not many notable differences between Oribe’s version and the published one, probably because both were based directly on the same source.

⁶Mono-kazu no han-no-kazu wo oshierareshi nari [物數の半の數ををしへられし也].

Mono-kazu [物数] means the total number of objects.

Han-no-kazu [半の数]: han [半], in this case, means an odd number of (objects), rather than "half" (as the kanji han is usually understood). As has been explained previously, han [半] (odd) and chō [調] (even) are the operative words in the theory of kane-wari, referring to yang and yin elements, respectively.

Oshierareru [教えられる] means “be taught,” though with the additional nuance that the material has been handed down from earlier times.

The structure makes it clear that this sentence was not added by Rikyū. Nor by a first-generation disciple -- someone like Nambō Sōkei, for example. Rather, oshierareru suggests a passage of a long span of time -- at least several decades -- between the time when the teaching was first expressed, and the time when this comment was added. It would be appropriately found in a comment appended in the early Edo period (which seems to have been when a person, acting on behalf of the Sen family, made bold to incorporate spurious material into the documents that were preserved in Sōkei’s wooden chest, in the Shū-un-an).

0 notes

Photo

3/18 元浜とごはん みーちゃんとお出かけ 餝屋 3/19 ちーやんりことお出かけ はる屋terrace 3/20 現実へ

0 notes