Text

OVERVIEW

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines FGM as “all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” FGM can lead to childbirth complications, menstrual issues, scarring, loss of sensation, cysts, boils, infections, and more. FGM is found in over 30 countries with over 200 million girls and women between the ages of 15 and 49 have undergone the procedure. The purpose of the procedure is to eliminate the nerve endings that produce sexual pleasure to discourage girls and women from engaging in premarital sex. It is seen as virtious and that girls and women who are uncut are “loose, promiscuous, and used.”

0 notes

Text

Types of FGM (As defined by the UN)

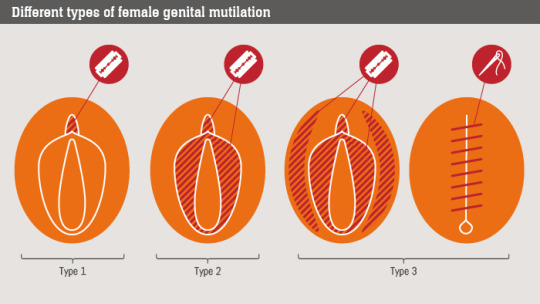

Female genital mutilation is classified into 4 major types:

Type 1: This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (the external and visible part of the clitoris, which is a sensitive part of the female genitals), and/or the prepuce/clitoral hood (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoral glans). [Also known as Clitoridectomy]

Type 2: This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without removal of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva).

Type 3: Also known as infibulation, this is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoral prepuce/clitoral hood and glans.

Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g., pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

0 notes

Text

Griffin, G., & Jordal, M. (2018). Resistance to reconstruction: the cultural weight of virginity, virility, and male sexual pleasure Body, Migration, Re/constructive Surgeries : Making the Gendered Body in a Globalized World (First edition..). Routledge.

This article explores the relationship between persons who have undergone Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and reconstructive surgery. The form of reconstructive surgery that this article is exploring specifically is defibulation which is a procedure that reopens the vaginal opening of those who have been infibulated. Infibulation, also known as Type III FGM, is the the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The clitoris and labia minora are typically removed in this type as well. In order to understand the hesitancy of undergoing defibulation the article delves into the cultural and social values of societies where infibulation is performed in.

The research study was conducted in Norway and examined the Somali and Sudanese community in Norway. The author also visited and stayed in both countries as part of their research in order to get a better understanding of their cultures. This research study was primarily a qualitative study and the data was collected through interviews. Participants were gathered through snowballing within each respective community.

The article sought to answer why medicalized defibulation was not commonly sought after, despite the health benefits associated with it. Medicalized defibulation is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Norwegian Health Authorities, but only 120 consultations are reported annually despite there being approximately 17,300 girls who have undergone FGM with approximately 9,100 of those girls having been infibulated. However, in order to understand the reason why there is a socio-cultural resistance to being defibulated there needs to be a proper understanding of why infibulation is practiced in the first place.

The author states that “The cultural meaning of infibulation is tightly intertwined with the physiological extent of the procedure.” The scar and opening that is left is purposely made small to prevent intercourse in order to ensure and impose virginity. This procedure also ensures that if a woman were to lose her virginity it would be physically clear and marked on her vagina. An infibulated woman is regarded as a woman of value versus women who aren’t are considered loose, sexually promiscuous, and immoral. The article also discusses how this procedure ensures that women will produce children of undisputed paternal lineage which is considered extremely important in both Somali and Sudanese society as they are both divided into paternal lineage based clans. The article also discusses how amongst some families and subcultures that the husband defibulating their wife with pressure from his penis is an important part of proving their manhood. Along with that, it is culturally believed that infibulation keeps a woman’s vaginal opening “tight” to ensure pleasure for the male. This stems from the belief that having a “tight” vagina is pleasurable for the male and that being able to provide male pleasure is the most important part of sexual intercourse alongside fertility.

This article relates to my final paper topic, because it discusses FGM as socio-cultural issue and not just a medical issue. This article also gives me insight on the socio-cultural reasonings and meaning behind FGM and the socialization and subsequent stigma for those who have reconstructed surgery and those who do not have the procedure done in societies and cultures where FGM is the norm. It also gives me insight on the socialization and subsequent stigma for those who have undergone FGM and are in a society where FGM isn’t the norm. The article explores FGM’s relationship to gender which is very important in this social context. The article also delves into how FGM influences both perception of and experienced sexuality for those who have undergone the procedure which is very overlooked. When discussing FGM and sexuality many research articles approach it in a fully medicalized way and as a result insinuate that those who have undergone the procedure lack a sexuality. This article acknowledges that these women are still sexual beings with a capacity for sexual desire and pleasure and takes that into consideration throughout the study.

0 notes

Text

“It is based on the supremacy of the man, the express purpose being to produce children of undisputed paternity, such paternity is demanded because these children are later to core into their father's property as his natural heirs. It is distinguished from pairing marriage by the much greater strength of the marriage tie, which can no longer be dissolved at either partner's wish. As a rule, it is now only the man who can dissolve it, and put away his wife. The right of conjugal infidelity also remains secured to him, at any rate by custom (the Code Napoleon explicitly accords it to the husband as long as he does not bring his concubine into the house), and as social life develops he exercises his right more and more; should the wife recall the old form of sexual life and attempt to revive it, she is punished more severely than ever”

“Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State.”

0 notes

Text

Several women mimicked the stiff, uncomfortable walk they associated with newly wed women who suffer from painful wounds and infections of the vulva. A couple of men also lamented the misnomer of the term ‘honeymoon’ as a description of the new-lywed period on these grounds.”

“Resistence to reconstruction: The cultural weight of virginity, virility, and male sexual pleasure.”

0 notes

Text

Bayoumi, R. R., & Boivin, J. (2022). The impact of pharaonic female genital mutilation on sexuality: Two cases from Sudan highlighting the need for widespread dissemination of sexual and reproductive health education in Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 26(1), 110–114. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2022/v26i1.12

This article presents 2 case studies of women who have gone through FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) in Sudan. In the case studies the women, both of whom are struggling with infertility, describe how they believe that FGM affected their sexuality and the sexual difficulties they have faced as a result of the procedure. The article then examines their stories and analyzes them through the lense of sexual satisfaction and cultural views on sexuality and sexual education. The article then discuss both the societal factors that contribute to high FGM rates especially within Sudan and Somalia.

The article uses both qualitative and quantitative data retrieved from the WHO (World Health Organization) and a myriad of Women’s health and reproductive academic articles and journals on FGM. The main focus of the article is the 2 case studies presented and the remainder of the data is used only to supply background information and support the article’s findings. The article focusses on Sudan and Somalia when discussing the culture around FGM and the reasonings for it, because they have the 2 highest rates of FGM globally with Sudan at 88% and Somalia at 98% according to WHO. These numbers are based on the amount of women aged 15-55 who have undergone FGM in the country. The article is written from a position that condemns FGM and aims to show how it negatively impacts those who have undergone the procedure and different ways to prevent the procedure from continuing. The article emphasizes the importance of sex education in preventing the continuation of FGM and the lack of sex education in many FGM practicing countries. The article claims that the lack of proper sex education in these countries is a major contributing factor to the high prevalence of FGM as well as the stigmatization of female sexual pleasure and desire. The strongly patriarchal culture in these countries as well as the burden placed on women to produce children of undisputed paternity is touched on. Not only that, but women’s role in carrying out FGM and enforcing it onto future generations.

This article relates to my topic because it talks about the secuality of the women who have undergone FGM. Many times their sexuality is over looked or completely dismissed when discussing FGM, because the focus is solely on whether they are able to give birth without complications or if they retain any sensations. Majority of the articles that I would come across only discussed FGM from a medicalized point of view when in reality FGM is just as much of a social issue as it is a medical issue. It is important to understand the socio-cultural conditions that have allowed FGM to be practiced and continue to be practiced as well as how it directly impacts the livelihoods of the girls and women who have undergone this procedure. Not just what their potential birthing experience will be like or their risk for other complications, but also how it impacts their sexuality, relationships, and sense of self and belonging within their community.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this article as it pertains to my research. This article was originally written in French, at least from what I could gather from the abstract, so during translation there may have been words that had slightly different connotations in English then it would have in French. It should also be noted that in one point in the article they used quantitative data on how women who have undergone FGM feel their sexual satisfaction is compared to other women. While this is very important data to collect, analyzing it in a ranking system leaves a large room for error because there is not a set definition on what a regular satisfactory sexual relationship that a woman should have is for each person. Some women’s answers may be influenced by sexual shame or stigma of female sexual desire and pleasure in their culture. The article briefly acknowledges this point.

0 notes

Text

“Not having a clitoris was experienced as a limitation, including on the symbolic level, in terms of a compromised femininity. My women respondents said that with ‘no clitoris’ they did not feel like ‘real women’. If defini-tions of womanhood and femininity deal with sociocultural constructions and differ across time and place, for excision-affected women, living in France and engaged in a medical process towards clitoral reconstruction, the clitoris became a central aspect of those definitions.”

“The need for clitoral reconstruction: Engaged bodies and committed medicine.”

0 notes

Text

“There's this one thing that has affected my life the most. Like a teacher of mine once said, if there was a way to get an implant, I would get one [anatomically correct genitalia] ·. Honestly, I'm suffering from the Pharaonic Cutting. You know in Pharaonic Cutting, there's nothing, do you understand me? I don't feel like other women, I don't feel comfortable and stuff... I'm convinced that this [FGM] has had an impact on me! I won't lie to you, it has an effect, you feel like you are cold [sexual frigidity]. This Coldness Comes, For No Reason, Not From You, They Took Your Stuff [Genitalia] They tell you it's from the brain [sexual arousal], the brain sends a signal to the stomach that you are full, but how can it send a signal, where to send it? There's nothing there [no genitalia to receive the signal of sexual arousal from the brain]. People would have trained themselves, if it was from the brain. This is something [the genitals] God put there, did he just put it there for nothing? And when I read about the nerve endings that are there, more than the rest of the body, when you just take it all away, what does that mean and when you close it up like that... I mean people like us, how can we treat ourselves? Without surgery, some people say they take pills, like Viagra for women, but it [the pill] is supposed to go and work on this organ, but the organ is not there! Wouldn't you feel that was a problem?”

“The impact of pharaonic female genital mutilation on sexuality: Two cases from Sudan highlighting the need for widespread dissemination of sexual and reproductive health education in Africa.”

0 notes

Text

Stew, Tabi. 2019. “IS THE TABOO OF FEMALE SEXUALITY THE SOLE CONTINUATION OF FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION IN EGYPT?” al-Afkar, Journal for Islamic Studies 4(1):147-70

This article aims to ecplore whether the taboo of female sexuality in Egyptian culture is the sole reason that Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is still prevelant in Egypt today. The article does this by taking into consideration major influences on Egyptian culture such as religion, specifically Islam. It is believed by many Egyptians that FGM helps promote chastity and discourages girls from engaging in premarital sex by reducing their sexual desire. The emphasis on ensuring virginity until marriage and discouragement of female sexual desire is a prominent reasoning in cultural and religious justifications. The article emphasizes on the importance of not reducing FGM to a “cultural practice” as it takes away from the main issue with the practice and in a way legitimizes the procedure through language.

The majority of the population of Egypt are muslims and thus follow Islam. Many justifications of FGM in both Egypt and other muslim populations worldwide is that it is Sunnah to practice FGM. Sunnah is defined as the traditions and practices of Prophet Muhammad that muslims should follow. Sunnah is not mandated to follow as what is considered Sunnah is not in the Quran (although there may be overlapping) but it is encouraged to live like the Prophet Muhammad to be holy. There are also Hadiths that some Islamic scholars use to justify FGM. Hadith are sayings from the Prophet Muhammad or his companions that are not required to be followed but it is believed that whoever does follow the Hadiths will receive more good deeds also known as Ajar. There are no Hadiths requiring or encouraging FGM and it is not considered a valid act of Sunnah. However, due to the false belief that FGM will make girls and women not engage in any sexual activity and rid them of sexual desire many people justify it as Sunnah that way despite it not meeting the requirements to be defined as Sunnah. It should be noted that FGM existed in Egypt before Islam and was even found on Ancient Egyptian mummies.

This article stresses the importance on language regarding FGM. Describing FGM as a cultural practice in a way justifies the practice, disassociates the West from it, and leaves more room for racism and Islamophobia. By labeling FGM as a cultural practice it demands respect for the procedure and leads to encouragement of some form of cultural preservation. FGM is a harmful procedure with no health benefits and only exists to deny girls and women sexual autonomy. FGM was also prevalent in Western countries in the past and framing it as a cultural practice denies that history and that it still happens in Western countries. It also makes FGM seem like a “third world” or Islamic world issue thus opening up the criticism of the practice to be based on racism and Islamophobia rather than its impact on girl’s and women’s lives.

Egypt has one of the highest rates of FGM in the world despite having a higher education and literacy rate then other countries where FGM is also prevalent. While sex education in Egypt is relatively low it is well known that FGM is not done for health benefits but as a preventative measure to preserve chastity. Despite it not having any health or medical benefits the procedure of FGM has been medicalized heavily in Egypt. Instead of being done by an elder woman whose training has been passed down through previous generations of practitioners it is now commonly done in a medical office by a licensed physician as a way to legitimize the procedure. The physician who conducts this procedure in the vast majority of cases is a man. This helps advertise the procedure as more safe and technical in an attempt to eliminate all of the negative health side effects of FGM while excluding sexuality from the equation. While the risk of sepsis and other infections is lowered by the medical setting the psychosexual damage remains.

This article is important to my research, because it discusses the beliefs and reasonings behind FGM in Egypt where FGM is prevalent. It also explains the connection between FGM and Islam and other cultural beliefs. Knowing this information is important, because FGM is as much of a socio-cultural issue as it is a health issue. These cultural beliefs are what allow FGM to continue in these countries so knowing and understanding them is important in order to properly address the issue.

0 notes

Text

“The importance of honour and the preservation of chastity in Egyptian society continues to prevail in modern Egyptian society, and medicalisation legitimizes the practice among the educated elite.”

“IS THE TABOO OF FEMALE SEXUALITY THE SOLE CONTINUATION OF FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION IN EGYPT?”

1 note

·

View note

Text

They [women] will not go after men. The blood heat [sexual desire] will cool.Men will not be envious because women that are cut will not go for other men. (Naeku, 25-year old female, Narok)

“Plurality of beliefs about female genital mutilation amidst decades of intervention programming in Narok and Kisii Counties, Kenya.”

0 notes