Text

Why I left the physician-scientist track

I don't get the physician-scientist job. I mean… I get it, but I don't get it. And it all makes me sad. Let me try to explain.

About a month ago I graduated residency and over the past year I poured mental energy into analyzing my first post-training job. I browsed all sorts of jobs in all sorts of places, but what I really wanted was an academic job. For years I’ve wanted a job that combined interesting and helpful. I wanted to help people that I was uniquely suited to help, people that wouldn’t get help without me. I also wanted the job to be intellectually stimulating, and sometime around 10 years ago I decided the best path was the academic physician-scientist. I went to an MD PhD program, got a PhD in molecular biology, competed for NIH grants, and developed a coherent vision for how my clinical and research worlds would overlap. When it came time to my job search I spent a whole lot of time cold-emailing department chairs and various administrators about the vague possibility of a physician-scientist job. Most of the conversations went nowhere but the rare conversation progressed a little. sidenote - I should say that the kind of physician-scientist I wanted to be was kind of a weird niche. I wanted to be a family medicine clinician working on the molecular mechanisms of alcohol and drugs affecting the placenta. My vision was that as a family medicine physician I would take care of women during pregnancy, take care of kids with developmental problems, and also manage substance use disorders. Maybe this was too broad of a clinical interest and maybe family medicine wasn’t the best specialty for research but I also thought this was kind of a creative way that I could use my basic science skills to help understand these complex patients that are getting lost in the cracks of the medical treatment behemoth. But either way, you can probably imagine that this work is kind of a niche within a niche and there were very few options of academic medical centers where I found suitable basic science mentors and supportive clinical departments. I think this was a major pitfall of my job search and I think (maybe naively) that if I had followed a more traditional track it would’ve been easier.

Anyways, when the conversations with department chairs and scientists progressed, it ultimately fizzled out when we got to figuring out who would pay for what and how much I would get paid. sidenote - During my years of MD PhD training I heard the buzzword "protected research time" about a million times. It was drilled into us. When we finally got to the point of looking for a post-training job we needed that protected research time. We needed to constantly be on the guard against administrative duties and clinical departments encroaching on our precious protected research time. I get it. The basic research life is such a grind. When I was a grad student in the lab I was working longer than I did during residency if you can even believe that. And even at that level I felt like I was just barely on the track to make it as a professional physician-scientist. So when I was looking for a physician-scientist job I asked for one or max two clinical days a week. My logic was that in the beginning of my career I needed as much protected research time as I could get so I could get grants to pay other people to help execute my research vision. This turned out to be quite the challenge.

This job search was when I finally understood what protected research time means. It’s basically one of two things: 1) Academic departments gambling their little money on young researchers or 2) Young researchers working for free. The end goal of a physician-scientist is for us to obtain grants that pay our salaries while we participate in non-clinical activities like research, but there’s kind of a conundrum there. How are we supposed to get those grants without some initial salary support? When I talked to clinical departments they essentially had no seed money to offer me and they had the idea that I would work 3 or 4 days a week in the clinic. When I talked to research PIs they had no interest in funding a 1 day a week postdoc and thought they could scrounge together some salary from institutional research grants but of course this was a maybe, in the future, kind of thing, so I’d have to start out by either working for free while I waited for the possibility of eventual funding or agree to do a fellowship where my research time would be protected, except my compensation for my clinical work would be severely reduced.

I didn’t love this idea, mainly because I just found it fundamentally unfair. Why would I, a fully-trained clinician, willingly give up $200,000 a year in salary, the stability of a long-term job, and continue doing other people’s grunt work to have 2 or 3 days a week dedicated to research? That’s the cost of pursuing a career as a physician-scientist? Is that reasonable? I mean, I get it. We do it because we love the work, or because of our noble commitment to our patients. and maybe I just lost that drive, but I just don’t think it’s sustainable to have an entire arm of the biomedical world depend on the good will of hard-working individuals. It’s already hard enough to find physician-scientists but I think the to-be physician-scientists are going to be increasingly frustrated with the career track. I just don’t see millennial or gen Z-ers wanting to put up with all the shit that comes with being a medical trainee for all the extra years only to get paid less than their peers for doing more work. Where I live it’s almost becoming a norm for physicians to work 4 days a week. I can’t even imagine convincing residents to sign up to work the 10 days a week it would take to manage the two full-time jobs of physician-science.

Putting aside the question of whether people will go into physician-science, I think the major question facing physician-scientists of the future is whether they actually provides added value. I get the idea, physician-scientists are supposed to bridge the bench-to-bedside gap but it’s usually not that simple. The process is incredibly expensive, complicated, and time-intensive. It’s easily too much for one individual and accordingly a lot of this is driven by pharmaceutical companies. In my personal situation the actual mechanics of being in the clinic and doing basic research work just didn’t make sense. All the time I put towards western blots is just time for my clinical skills to wilt away and all the time I put towards dictating a physical exam is time spent away from another experiment. I would argue the only reason I could add value as a physician-scientist is if I did both of those jobs but got paid for one, which really only helps the bottom line of academic centers. And I hated that prospect. If I was sacrificing to help a patient or a colleague that was also sacrificing for me, that would be one thing. I’m not sacrificing for the administrators running an academic medical center that increasingly resembles for-profit companies like Amazon.

This is ultimately the most disappointing revelation I’ve seen about the physician-scientist. So much is about money. More and more physician-scientist work is about collaborating with industry to bring in money for a university that only wants you if you’re going to make them money. The old dream of taking my own bench finding and taking it to the clinic to help actual real-life patients is exactly that, a dream. Maybe I was just naive. Maybe I just expected too much.

On the other side of all those thoughts, my first post-training job is private practice rural family medicine physician. Ultimately I concluded, for myself, that the academic physician-scientist has an opportunity to help real life people but it just wasn’t the most intellectually stimulating work in medicine. I felt that was in rural family medicine. I think the creativity in medicine lies in synthesizing all of the findings from different subspecialties and blending that to help the individual patient in front of you. The demand in rural medicine protects me from the administrators pushing me onto the 30-patients-a-day primary care treadmill so I have time to read the primary literature. I’m also away from the protocols and specialists at a big academic medical center that dictate my clinical decisions so I actually have the freedom to come to my own data-driven conclusions. And finally being in an area surrounded by social determinants of health for miles and miles fixes my desire to be needed and do work that maybe wouldn’t be done without me. I’m still trying to figure out how, or if, research falls into this life. Maybe I’ll get a remote MPH and work on some clinical research or maybe one day I’ll wake up and it’ll be time to look for a teaching job at an academic center. I don’t know. But for today I get to spend an afternoon off thinking and I’m grateful for that.

see you on the other side,

from ken

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would I prescribe medical marijuana?

"Oh before I leave I have one last question." The dreaded hand-on-the-doorknob question. The question was usually, "I've been having trouble in the bedroom," but a new one I got recently is, "So can I get a prescription for medical marijuana?"

South Dakota decided to legalize medical marijuana and is considering legalizing recreational use as well. The whole legal process is very complicated and I don't really get it but I've been doing my best to follow along with the local media. What I understand so far is that according to the federal government medical marijuana is illegal but multiple states have allowed it to be prescribed to patients and some have even allowed it to be used recreationally. Every state seems to have a different set of confusing regulations but at least in South Dakota marijuana is technically not prescribed but rather physicians credential patients to be eligible for medical marijuana. There's a list of diagnoses that qualify for medical marijuana AIDS, HIV, ALS, MS, cancer-related pain, Crohn's disease, Epilepsy, PTSD, and glaucoma. sidenote - The card allows patients to go to a dispensary and obtain medical marijuana. I think some patients think being credentialed means they can carry around marijuana that they bought illegally and not get in trouble as long as they have a card for it but my understanding is that's not really what it does. Although, I don't get how the police would know if the marijuana was or was not obtained from a dispensary but that's besides the point. The major hospitals and medical groups in South Dakota have not yet released recommendations on how to prescribe medical marijuana and it sounds like October or November will be the earliest that there will be official guidance from the South Dakota Department of Health on how to qualify candidates as acceptable for medical marijuana. I should also add the caveat to all this that the two clinics I work at are currently not accepting the paperwork for credentialing patients to use medical marijuana. All that said, I've had several patients come to ask me about medical marijuana. I have even had one patient tell me that if I wanted to start prescribing medical marijuana I could become a millionaire in this town, so that's cool I guess. I think the greater point is for me to know a) if I'm for or against this, and b) whether I would credential patients in the future. I know patients are getting medical marijuana from the one dispensary in South Dakota but I'm just curious who's credentialing patients and what sort of logic they're using. Are they just tired of patients bothering them for pain or anxiety meds? Are they being paid by the marijuana industry? Do they really believe it has some positive effect?

I feel very conflicted about prescribing. The evidence is one thing. sidenote - the short story is that the evidence for medical marijuana is borderline. Some studies find some marginal benefit but most of the studies I've seen have a placebo effect that is bigger than the actual effect of the marijuana. Another confusing thing about the studies on medical marijuana is that we are credentialing patients to buy marijuana and then smoke it, but most of the studies on medical marijuana are on chemical forms of marijuana. Either some sort of extract or isolated chemicals that are found in marijuana. Is it really fair to go from these studies on chemicals being consumed by mouth to smoking a plant with that chemical in it? Also, isn't it a little funny for doctors to prescribe something to be smoked? Smoking is the thing doctors are most well-known for fighting. Doctors say smoking is bad. That's what doctors do. And now we're credentialing patients to smoke? The closest medical analogy I can think of is inhalers. sidenote - I wonder if anyone has ever looked into rates of albuterol inhaler use over a lifetime and lung cancer risk?

It's complicated though. While the evidence isn't a slam dunk, there is some evidence that it has benefits. That can't be said for all treatments that doctors prescribe, including some that are FDA approved. For me, the biggest potential for medical marijuana is as a harm reduction tactic. sidenote - harm reduction is this controversial idea in addiction medicine that seeks to reduce harm rather than eliminate harm. For instance, instead of focusing policy on arresting heroin users to eliminate heroin use, a harm reduction approach would be providing clean needles for IV drug users to reduce the risk of transmitting blood borne diseases like HIV and hepatitis C. It also allows IV drugs users to take steps towards thinking about getting off of drugs and it allows a connection between IV drug users and the healthcare field. So how does medical marijuana play into harm reduction? I feel like it could be used to wean patients off of potentially more dangerous medications like opioids for pain or benzodiazepines for anxiety. There is some evidence going along with this idea like the data that opioid-related deaths have decreased in states that have legalized marijuana. I should note that this data is highly controversial. Regardless, I have a patient who takes chronic benzodiazepines. sidenote - Benzo's are anti-anxiety medications like xanax, klonopin, or valium that inspired the Rolling Stones' "Mother's Little Helper." They're terribly addictive because of their rapid action but also the terrible withdrawal symptoms. Since I first met this patient on chronic benzo's I have been trying to wean him off of them because I'm worried about the long-term effects on his memory and other cognitive function. I also question if the medicine is doing more harm than good for his anxiety. Like, is it just acting as a bandaid so the patient can avoid developing coping skills to deal with the anxiety and thus leaving him less well equipped for future anxiety exacerbations? So this patient asked me for medical marijuana. I had to tell him no because of our clinic policy to not certify patients for medical marijuana but we did have a discussion about how he felt like marijuana helped him. He told me that if, at some point, I could credential him for medical marijuana he would agree to slowly titrate down on his benzodiazepines. Now, who knows if he would actually do that, and frankly I don't even know that medical marijuana is safer than benzodiazepines. There's not well-controlled head-to-head long-term studies that compare benzodiazepines and marijuana and there will never be such studies. But... if I had to guess, I feel like it is. Benzo's are dangerous. People die from overdosing on benzodiazepines. People combine alcohol and benzo's or opioids and benzo's and die all the time. These are lethal combinations. People are not dying of marijuana overdose. They are crushing stuffed crust pizza. They are discussing Michelle Foucault. They are taking naps. And there are consequences to marijuana too, cognitive problems, addiction, respiratory problems, chronic nausea and vomiting, but it's always been striking to me how much people feel like it helps their anxiety and pain. It can't all be placebo effect, can it? And even if it is largely placebo, is that fine?

At the end of the day I feel like the most appropriate approach is for legal recreational marijuana. This is probably an entirely different conversation and I don't want to get into it now but the short of it is that it feels unAmerican to say we can't use marijuana. Isn't this is the country of "Don't tread on me?" Isn't this the country of acceptance? But to go back to medical marijuana I think I lean towards thinking that it's not a good idea for medical professionals to give the okay to use medical marijuana. I think it'd be fine if we were prescribing chemicals isolated from marijuana like marinol but it seems like giving the thumbs up to smoke is outside of our range.

see you on the other side,

from ken

1 note

·

View note

Text

Is addiction a disease?

Is addiction a disease? This is a question I've been reading about recently. If you asked me three years ago when I was in med school I would have said, "Definitely yes. Addiction is a biological disease that is wired in the brain." Now that I've had the opportunity to take care of patients with addiction and related issues I'm a little bit more confused. First let's define addiction. It's hard to define but here's a couple definitions that I found:

- A chronic medical disease in which people engage in behaviors that become compulsive and continue despite negative consequences

- A strong inclination to do something repeatedly

- An inability to stop doing something despite harm

So I think you get the idea. The teaching in medicine is that a loss of control is the hallmark of addiction and there are certainly patients with pathology that screams classic addiction. The alcoholic that has liver failure so bad that his skin is yellow but still walks to the convenience store every morning to buy a handle of vodka and can't stop drinking even as his estranged family peers down from afar. But this patient is the extreme and really doesn't capture the majority of people who use illicit drugs, even those that are negatively impacted by drugs. There are people who smoke marijuana at the end of a productive work day in the same way another person might have a glass of red wine. The marijuana might help them sleep, but are they dependent and thus have addiction? There are yet others who use heroin to mask the pain they feel from their post-traumatic stress disorder. sidenote - In thinking about this question, it raises a secondary question. Does it even matter if addiction is a disease?

I've read arguments that addiction is not a disease because stating that addiction is a disease does a disservice to patients dealing with addiction. It portrays patients as helpless victims against an inevitable biological process. I get it. I don't disagree. I want what's best for people dealing with addiction. At the same time, shouldn't biology determine whether something is a disease? Should people with said condition be the one's to determine if something is a disease? sidenote - What, even, is disease? Here's some definitions that I found:

- A deviation from the biological norm

- A disorder of structure or function that produces specific signs or symptoms

- A reason to get sick pay

- A condition for which treatment by healthcare providers can be reimbursed

The last two definitions kind of sound like a joke. But like every good joke they are funny because they are half true. Disease is not a biological entity. Disease is a legal entity. Disease is something that the government agrees to pay for. Should we really grant this sort of power to popular opinion? Should a thing become a disease only if it's disturbing to a large chunk of society? sidenote - Perhaps the most famous example of whether something is a disease is 50 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association considered homosexuality a disease. This essentially became a disease because it was disturbing to a large chunk of society, and subsequently stopped being a disease once stating that homosexuality is a disease became disturbing to a large chunk of society. It doesn't really make sense, right?

From my perspective as a healthcare worker, the purpose of labeling a set of symptoms as a disease should be that labeling it helps you A) identify a treatment for that set of symptoms or B) prognosticate a future set of symptoms. Leg swelling, diarrhea, and difficulty breathing could be three completely different things but it can also mean heart failure. In this case it's useful to label these symptoms with the disease of heart failure because a certain regimen of medicines can help reverse heart failure. Leg swelling, diarrhea, and difficulty breathing can also mean colon cancer with metastases to the liver. In this case it's useful to label these symptoms with the disease of colon cancer because it can help you predict what will happen to that person next (die) and when (soon). For addiction, I think it's still early in our understanding of addiction as a disease. We can't reliably predict a person's outcome based on whether they drink alcohol and we can't reliably give people a medicine to stop them from drinking alcohol. I wonder if we are doing a disservice by lumping together all people that use illicit substances under the umbrella of addiction.

I don't have scientific proof for this next statement but I just feel like the patient with alcoholic liver disease that is so bad that their skin becomes yellow and still cannot stop drinking has some sort of brain mis-wiring that could be corrected by using medicine to alter the neurochemistry. But when it comes to the patient that becomes dependent on marijuana to sleep, does that person even have a pathology? Other than the thorny legal aspect, is that any different from becoming dependent on SSRIs? sidenote - a question I have been wondering recently is whether I would prescribe medical marijuana. More to come in a later post. And the patient that depends on heroin to numb the pain of their past trauma. Is their pathology addiction? Or is their pathology post-traumatic stress disorder?

So is addiction a disease? Yes, I think, but we need to continue to refine our understanding of addiction as a disease. The next step is developing sub-types of addiction. As an analogy I like to think about ankle fractures. An ankle fracture could be due to a one-time extrinsic trauma like rolling an ankle in a pickup game or an intrinsic problem like weak bones from osteoporosis. Maybe we define addiction the disease as out-of-control behavior which is induced by some thing. Using the framework of the ankle fracture analogy there could be addiction due to a one-time extrinsic trauma like child abuse or an intrinsic problem like a brain with poorly developed self-control mechanisms. I like this idea of sub-types of addiction. I can kind of see how addiction caused by different things would be easier or harder to overcome. Also that different treatments would be better for addiction caused by different things. I will have to think about this more.

see you on the other side,

from ken

0 notes

Text

F-15 Eagle

All stories loosely based on a true story.

Mr. Anderson is a 42 year old male with a past medical history of hypertension who initially presented to the emergency room with a chief complaint of a left arm abscess. He states it started out as a small spot that kept growing. He tried to pop it on his own but it just came back. He endorses subjective fevers, chills, and fatigue. Denies chest pain, shortness of breath, trauma, insect bites. He presented to the ER because he couldn’t deal with the pain.

On exam the patient is afebrile, tachycardic, has multiple tattoos and track marks on bilateral forearms. Labs show a white count of 19, AKI with creatinine of 1.3 (baseline 0.6), sodium of 133, and ultrasound shows a left arm abscess with a drainable pocket. Blood cultures are pending. The General Surgery service was consulted by the ER and recommended I&D in the morning. We were called to admit the patient and started broad spectrum antibiotics comma vanc-cefepime-flagyl comma IV fluids comma and NPO at midnight period new paragraph.

--

Ken: Do you drink alcohol?

Patient: Just on the weekends.

How much?

Maybe a 6 pack.

When you drink a lot, how much would you say you drink?

Like 15. But I’d be real hungover the next day. *Laughs*

Sure, sure. Do you smoke cigarettes?

Yeah.

How much?

Half pack.

Smoke marijuana?

Yeah.

How often?

Just sometimes. Depends when I can get it.?

Other drugs? Meth, cocaine, heroin?

Meth.

How often?

Everyday.

Do you inject?

I mostly smoke.

You know why you have this abscess?

Yeah, I know.

Sure, sure. *Looks around the room, uncomfortably* Anyways, do you take any medications everyday?

I’m supposed to take some blood pressure pill.

Any medication allergies?

Amoxicillin.

So why do you do meth?

What?

Meth. What do you like about it?

I guess ‘cause it’s cheap.

But so are cigarettes.

Yeah.

Look man, I’m just being nosy. You don’t have to tell me anything you don’t want to.

*Stares, for a second* It takes away the pain.

What?

I know meth doesn’t help pain. It just distracts me, I guess. My back’s messed up from a car accident fifteen years ago. I was gonna have back surgery but I got fired and lost insurance. You know I used to flip houses?

*Nodding*

You should see my MRI. My back is fucked up.

*Nodding* Errrr, well, that’s all the questions I had for you. Do you have any questions or concerns for me?

How much time you got, brah?

*Checks telmediq*

--

Meth for pain. Sounds weird, but if you think about it, it makes total sense. I’ve been trying to ask this question more, why do you use x substance? The first time I heard about meth for pain I was like wtf? But the more I heard it, the more it made sense. I mean, what is pain anyways? When my 6 year old daughter says her knee hurts I bust out my otoscope, look in her ear, tell her that nasal saline spray could help and then her stomach doesn’t hurt. My patient with chronic back pain that takes three Norco’s a day, she says her pain is better when she’s distracted with her grandchildren. My patient with chronic abdominal pain, it got way worse after he lost his job and he had to stay home with his now-home-schooling son with ADHD.

sidenote - I recently went to my first virtual conference, the American College of Medical Toxicology’s Symposium on Methamphetamines and Stimulants. I hesitated about a virtual conference but the residency paid for it so I decided it was worth a day. Overall, it was cool. I didn’t learn that much, which is good, I guess that means I’ve been learning a lot about methamphetamines from my residency. And we see way more meth than I was expecting. From an addiction perspective I was thinking we’d see a lot of cocaine, heroin, pills, but no. What we see is meth and alcohol. There’s some opioids for sure and I manage some bup but meth is everywhere. The conference did spark some thoughts in me, though. It made me wonder if meth use disorder is a disease, or a symptom of the disease. And if so, what is the disease?

During residency I’ve certainly come across stereotypical addicts. Patients that can’t stop drinking alcohol from the moment they wake up that present to the clinic yellow. Not just mild scleral icterus, like highlighter yellow. But that’s the exception, not the rule. Most patients are borderline on the DSM-V. Most patient qualify on the DSM-V substance use disorder criteria, but I just don’t feel like these patients are addicts, you know?

The more I think about the best way to approach meth use disorder the more it makes me think about what I’m thinking about. Is meth use disorder a disease? Is it actually untreated ADHD? Is it a way to treat emotional pain? Is it a way to treat somatic pain? Does it, in a sense, have the same underlying pathophysiology as opioid use disorder? Like, did heroin and pills get too expensive and meth got so cheap that the opioid use disorder population just changed gears and are using meth to treat the same problems? To take it a step further, is it a medical manifestation of poverty? Is it a physical manifestation of hopelessness?

--

Ken: Sure, sure. I got a few minutes.

Patient: Why can’t you fucking doctors treat my pain.

sidenote - this is a statement, not a question.

That’s a good question.

You guys are full of shit.

*Nodding*

Sorry man I’m not talking about you.

Sure, sure.

*Stares off at Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives*

Hey let me ask you a question.

What.

sidenote - again, this is a statement, not a question.

Would you consider yourself addicted to meth?

*Stares at me*

--

see you on the other side,

from ken

0 notes

Text

2021 New Year's Resolutions

2020, what a year. I can’t tell if it blew by or I crawled through it. I think the past year was so busy between finishing up intern year and having a front-loaded second year schedule that I finally have some time to stop and think. What I want in 2021 is to have more time to think. I feel like too often I was just operating on auto pilot this past year. I want to make an effort to be more aware of my daily activities but also thinking deeply about the problems of the world. So I planned my New Year’s Resolutions around this theme:

Individual goals

Write more

Meditate more

Read more

Family goals

Communicate with Katie better

Professional goals

Listen to Bedside Rounds

That’s a lot of Resolutions but I think it makes sense. Let me explain.

#1 Write more.

I’ve recently been doing a little reading about the growth of social media in medical education and how physician-authored blogs are being replaced by podcasts and twitter accounts because they are easy to consume. This definitely made me wonder if I should start a podcast but when I thought about it a little bit, I don’t really think that I write to reach a broader crowd or to disseminate my ideas or to become famous, I kinda think I like to write because it helps me to process my life and understand what I’m thinking. I heard somewhere that “Writing is thinking on paper and thinking is writing in your head.” I like that.

#2 Meditate more.

I’ve been interested in meditation for a long time. I think I was first exposed to it in college, so like 2006. Then I probably didn’t find much interest in it because it was hard and I forgot about it for a few years. Then I think I maybe started to think about it more during med school and grad school when I wanted to use it as a tool to control my stress and better understand how to not let my emotions overwhelm me but that again faded for reasons I don’t really remember. And now I think I’m having a third resurgence of interest in meditation. I think this third time, the best way I can explain why I’m intrigued by meditation is that it allows me to control my brain instead of my brain controlling me.

#3 Read more.

Here’s the list of books I’m reading/books I want to read:

Man’s Fourth Best Hospital and House of God by Samuel Shem

Why We’re Polarized by Ezra Klein

Meditation for Fidgety Skeptics by Dan Harris

Free of Me by Sharon Miller

Rez Life by David Treuer

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria by Beverly Tatum

The Highly Sensitive Child by Elaine Aron

A Promised Land by Barack Obama

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

The Great Influenza by John Barry

You can probably pick out some themes but I guess I want to read these books to prod me to think both more and less about the world. I want to think more about the topics that interest me and the problems that I think I can make a difference on, and at the same time think less about things the world wants me to think about. I also want to read books that Katie wants me to read because I want to care more about things she cares about.

On that note, #4 I want to communicate with Katie better.

I think over the course of the coronavirus season Katie and I have had an increasingly difficult time communicating and I think it paradoxically has to do with having more time around each other making us less value the time we have together and subsequently become further apart despite actually having spent more time together. I think especially as we start thinking about where we might move next and what sort of work I might focus on, I feel it’s important for us to be on the same page regarding our values so we can make a mutually agreeable decision on where to move after residency.

My last goal revolves around my job of being a doctor. Over the past 1.5 years I have learned a lot about being a doctor in terms of how to play a role in a hospital and also how to make medical decisions. sidenote - that first part, how to play a role in a hospital is what I call intern skills. This is basically like how to not get fired as an intern - knowing where/when to show up, how to work with nurses, who to ask specific recurring questions, who not to ask, things like that. The second part, medical knowledge is pretty self-explanatory and I have to say this because I don’t want everyone to think I’m done learning medical knowledge and how to function in a hospital but also I’m starting to wonder if I know enough about those things to get by and not commit malpractice. I recently decided to start moonlighting in a rural hospital, which I will start next month, in part because I feel like I should test out the hypothesis that I’m ready to practice independently. I guess what I’m trying to say is that my resolution #5 is I want to think about medicine as a whole. A major I was drawn to family medicine and generalist medicine in general is that it’s given me a general understanding of a lot of parts of medicine, generally speaking. I know a little about the latest trials in cardiology, a little about managing ADHD with both medications and behavioral changes, a little about delivering babies, but I want to learn more about how all these pieces fit together to serve some greater purpose. What I want is to improve my meta-understanding of medicine. sidenote - I think the more medicine progresses towards subspecialty silo’s there will be more value in generalists that can span different fields and not only ask but also answer interdisciplinary questions. I think part of what spurred this desire to understand the medical field is a book that I read about 100 pages of, The Great Influenza by John Barry. I started reading this at the recommendation of one of my faculty mentors and I liked it but I just couldn’t stick with it for some reason and I feel shame that I never finished this book. Anyways the book is about the 1918 flu pandemic and even in the 100 pages I read it was striking how similar our response to the COVID pandemic was to our response to the 1918 flu pandemic. It made me think: 1) Wow history really does repeat itself and 2) Wow we really haven’t learned anything. And so what I want to do this year is to listen to the podcast Bedside Rounds. It’s a podcast by a doctor that tells interesting stories in medical history. sidenote - I remember coming across this podcast a couple years ago and I disregarded it as kind of superfluous because it wasn’t teaching me any medicine. It wasn’t as important as listening to a Curbsiders episode about heart failure or a Clinical Problem Solvers episode about differential diagnosis of abdominal pain and I guess that’s maybe the point of me feeling like I’ve growing as a doctor. I feel like in the 1.5 years I’ve gotten good enough at medical knowledge and I want to take this opportunity to learn about the peripheral parts of medicine. I hope that these five things will make me a better person this year.

See you on the other side,

From ken

0 notes

Text

Who should get the COVID vaccine?

So we have the COVID vaccine, and that's great, but now the question that I'm wondering is,"Who should get the COVID vaccine?"

The CDC came out with a tier system including levels 1a, 1b, 1c, and 2. Level 1a includes healthcare personnel and long-term care facility residents. Level 1b includes persons age >75 and front-line essential workers including firefighters, please officers, postal workers, grocery store workers, teachers, childcare workers among other jobs. Level 1c includes persons age >65, persons age >16 with high risk medical conditions including but not limited to heart disease, diabetes, pregnancy. 1c also includes additional essential workers that are not quite as front-line including finances, construction, food services among others. Level 2 includes everyone else. sidenote - I love that somebody thought of this 1a, 1b, 1c thing. I mean, of course someone did. This is marketing genius. Nobody wants to be level 4. Instead of levels 1, 2, 3 we will have levels 1a, 1b, 1c. Everyone is level 1! But this is besides the point. This is besides the points.

The first point is that a bunch of healthcare workers have already gotten one vaccine and somewhere in the ether is a second vaccine that is reserved for us in a -80 degree freezer. Just sitting and waiting until we reach 6 weeks when we will receive our second vaccine. This sounds great that our second vaccine is secured and waiting for us, but here's the problem. We could be using these vaccines to immunize twice as many people and then waiting for more vaccines to show up, and even potentially delaying the second dose for healthcare workers out until 12 weeks to buy more time to immunize a higher percentage of the population. Now this may be a major bummer for healthcare workers but there may actually be a public health benefit to having twice as many people that are vaccinated and protected to some unknown extent than having half as many people that are protected to a known extent. And I have seen much debate on Twitter about how much protection one round of vaccines could offer. The punch line is that there is no clear answer but there is also data to suggest that protection from the COVID vaccine starts around 10-14 days and the protection from one shot is >90%.

The second point is whether healthcare workers should even be getting vaccinated first. Healthcare workers are mostly young and healthy, well protected with personal protective equipment, and many healthcare workers have minimal contact with COVID. I have seen the argument that healthcare workers deserve the COVID vaccine. I do think being a healthcare worker at this time has been hard but 2020 was terrible for everyone and this seems like a thorny argument that leads down a slippery slope. For instance, does a billionaire hedge fund manager deserve a COVID vaccine because of all the tax dollars he has put into the development of the vaccine? Does a scientist working at Pfizer that has no COVID exposure and has ample PPE deserve a vaccine? And the question isn’t whether healthcare worker should be getting vaccinated first but rather what is the best vaccination strategy? If the goal is to maximize the prevention of COVID mortality it is possible that vaccinating all long-term care facility residents and persons age greater than 75 should be the priority because these other people dying from COVID. If these people could be protected maybe less people would die of COVID.

The third point is a question of global health and the ethics of selling and profiting from the vaccine. Currently, governments including the US are buying COVID vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca etc. and essentially participating in a bidding war over the most valuable commodity on the market. Any such bidding war puts rich countries at a major advantage. This also allows the pharmaceutical companies to drive up the prices on the vaccines and make it harder for people to get them. But what about healthcare workers in Africa? What about long-term care facility residents in Mexico? Do we have a responsibility to help distribute the vaccine with a strategy that doesn’t just seek to minimize US COVID mortality but one that prioritizes limiting global mortality? In such a bidding war should the US be spending tax dollars to protect people from other countries when there are still US citizens that are unprotected? We’ve set up our healthcare and health technology to depend on an incentive system that revolves around money motivating people to produce results. Why should the Covid vaccine be any different? I am not sure what the answer to this question is, and it stresses me out.

See you on the other side,

From ken

0 notes

Text

Thoughts on the COVID vaccine Part 1- Incentives in science

I still cannot believe how fast pharmaceutical companies came up with the COVID vaccine. This has to be one of the greatest scientific achievements in history. The fact that it uses a novel strategy of injecting mRNA, how well it works, and how fast it was made is simply mind-blowing. Still, I cannot help but notice that the success of this vaccine stands in stark contrast to a large majority of the rest of COVID research which is largely not useful, sloppy, and at times dangerous. What frustrates me is that I suspect many scientists saw COVID as an opportunity to publish in a high-impact journal to further their careers, and I think this speaks volumes about the incentive structure of science.

For those not familiar with scientific careerism, this is how science is incentivized: in order to become a card-carrying scientist you need to obtain grants. Grants are sums of money that primarily come from the government to fund scientific projects. In order to get these grants you need to write stories to convince people that your idea is good, but it’s not just about the quality of your idea, it’s also about proving that you’ve been a productive scientist in the past. And herein lies the big big problem. It is incredibly difficult to define productivity in science. In fact, this may be impossible. sidenote - assessing productivity is not exactly easy in medicine either and current metrics like RVUs are far from perfect but I would much rather be judged by RVUs than Impact Factor if that tells you anything about the state of getting a job in science. Primarily, productivity in science is measured by publishing papers in high-impact journals like the New England Journal of Medicine, Science, Nature, Cell, JAMA. The kinds of names that are recognizable to non-scientists and the kinds of journals that clinicians deem legitimate. As a result, everyone wants their articles published in these journals and it becomes competitive. And this sort of competition can be good. Theoretically this should push the best science to the top. But things never work like they should in theory. That’s why we have science. Scientific publishing has a problem of incentives and the science that rises above isn’t the best but rather the science that will attract the most clicks and generate the most ad revenue. The problem with science is that scientific publishing has become big business.

Scientific publishing companies own journals and set up paywalls to read their articles. In response, academic institutions pay to subscribe to these journals, but these aren’t like $10 Netflix subscriptions. The University of California pays $11 million annually to the scientific journal publishing company Elsevier. And think about it like you’re Elsevier – you want to make the most money possible so you’re looking for articles that bring in the most clicks and generate the most advertising revenue. All this puts scientists in a weird place. If you want to get a job, or keep that job in science you’re incentivized to pursue click bait science and the result is a lot of work that tries to be flashy without having much substance. And frankly that’s a lot of COVID research. sidenote - The greater problem is that there is really no such thing as the best science. There are some basics that science should fulfill: 1) Clear hypothesis based on existing literature, 2) Controlled experiments that definitively rule out a hypothesis, and 3) Honest interpretation of these experiments. But beyond that I don’t know how anyone can say that one project on transcription factors that regular cancer metastasis is better or worse than characterizing cells that regulate vasoconstriction in the brain.

And it’s fine, I get that COVID research is going to get a lot of clicks right now. I consume a lot of that research because it’s interesting and pertinent not only to the clinical world but the world period. But the problem is when COVID research getting a lot of clicks gets misunderstood as a measure of its quality. sidenote - There is a famous quote in science that I love. It states:

“If I have seen further, it is because I have stood on the shoulder of giants.”

The paper that described the COVID vaccine was published in the New England Journal of Medicine and I give these authors all the credit in the world. The COVID vaccine really is awesome. At the same time, this vaccine was not birthed within the four walls surrounding Pfizer. This vaccine has been in the pipeline for years before SARS-CoV-2 came to Wuhan. This vaccine was built on the shoulders of immunologists that painstakingly discovered the spike protein, the molecular biologists that unearthed mRNA, and the bioinformaticians that figured out how to compare the genetic sequences of different Coronaviruses. Nobody could have predicted that an RNA virus would wreak havoc upon society in 2020 and nobody can predict what sort of health problems will fall upon society in 2030. If we allow scientific jobs to depend on sexy click-bait findings like COVID we will disincentivize all the work that paved the road for the COVID vaccine. Think about where we would be without the scientists that were studying Coronaviruses before COVID. Now that I’ve described the problem of misaligned incentives in science I feel that I should discuss the solutions to realign the incentives, but I still need to think some more.

See you on the other side,

From ken

0 notes

Text

201213 Residency in the time of Corona; Do I even have friends?

Herein, I wish I could find a really cool way to try to describe why 2020 has been a challenging year.

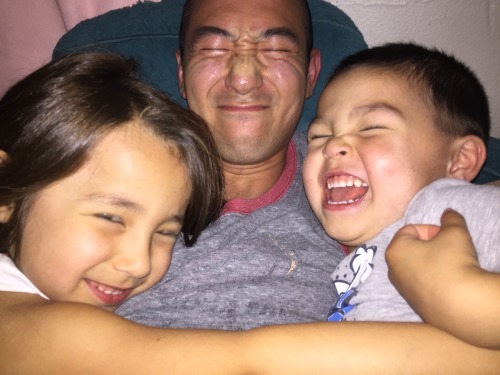

Recently it was my birthday. I had the pleasure of spending this time with my family. It was a nice birthday, but with all due respect to my kids, I wished I was spending it was my peers, like, my friends. Is this bad? Am I a bad dad for feeling this?

Herein, I try to capture the difficult tension between being present for my kids but also away from my kids so I can be myself.

I think the best thing about COVID is that it’s forced? me to spend more time with my kids, and it’s forced my kids to spend more time with me. And there’s no rigorous way to say that these moments wouldn’t have happened without covid, but I can just think of so many seconds-long-moments with my kids that I wouldn't trade for the world. Like there is this moment I can't get out of my head where we kept putting on layer on top of layer on top of layer of pajamas. We were so fluffy. I don’t even know why but we just kept putting on more layers. And we laughed and we laughed and we laughed. But at the same time, I was just thinking about this concept of friends. I think, in my past 10-15 years of existence, the concept of friends has probably been the most important thing to me. sidenote - in the 7th grade I was in a health class in which we had to bid a certain number of imaginary dollars on an idea. One might be a satisfying job, another might be going to the college of your dreams, yet another might be the opportunity to maintain close contact with your family, or the possibility to win the Pulitzer Award, or to be athletically fit for the rest of your life. You had to bid on the one you wanted, and if you were the one that bid the most you won that category. You were the person that valued your immediate family. You were the one of a million that was driven enough to win the Pulitzer Awards. The one I won was maintaining close relationships with my friends for the rest of my life. This sounds like a touching option to choose, but honestly I don’t know why I picked this because I didn’t have particularly good friends at this time. In retrospect there is probably like one friend from high school that I still speak to. There are certainly more, like five, that I wish I still spoke to but I don’t. I can’t explain why but for whatever reason I don’t. I believe this is normal.

Herein, I wonder if I even have people I could spend time with.

Anyways, what I was wondering on my birthday, and even longer, what I’ve been wondering over the past six months is, “Do I even have friends?” My intern year, the first year of my residency, I was so busy that it makes sense that I never even thought about whether I had friends or not. I was just trying to keep my head above water. But now that I made it through the mad dash of intern year, now that I have air to breathe, I have the leisure to sit back and think, “I should hang with my people.”

Herein, I blame my kids for being socially unfulfilled.

And I don’t know if it’s the time of life that I don’t have my people. Like, i have little kids. Much of my social energy, of which I don’t have that much, is spent on my little kids.

Herein, I feel bad for blaming my kids so I find something else to blame.

And I don’t know if it’s the place. Sioux Falls is the smallest place I’ve ever lived. This is the most midwest place I’ve ever lived. Which is weird when I think about it. Sioux Falls isn’t exactly a small place when I think about the place I might live next.

Herein, I blame COVID because it’s a safe thing to blame. Who could be mad for blaming COVID? Nobody could possible be for COVID.

So then there’s COVID. sidenote - the thing I like the best. The thing I like better than anything. The thing I miss the most is hanging out, drinking beers, and talking. I just miss that. I miss being around people I’m comfortable with and talking unhindered about the life going around us. And I can’t exactly decipher if I don’t have that now because of COVID, because there are weird non-law social pressures that say we shouldn’t hang out, or if it’s because I live in the wrong place, or if I’m just in a time of life when it’s hard to have friends, or if it’s some other reason I haven’t even thought about yet.

Herein, I wish I could find a way for all of us to have a big hug and appreciate how hard 2020 year has been.

sidenote - I feel like the pandemic hit at the worst possible time for me. I had been living in Sioux Falls for about 9 months when it hit. This was right around the time when I had met enough people to know which people I actually wanted to spend time with, but then the pandemic hits, and I hadn’t been friends with these new friends long enough to rely on them but I had also been too far adrift from my old friends and I was just left in this weird in-between. My instinct, if I had to redo 2020, is that this whole time we should have been hanging out and sacrificing ourselves for the sake of a life worth living. Is that wrong? I feel like it’s wrong to say that.

Herein, I wish I could describe in a really cool way that I hope 2021 is different.

see you on the other side,

from ken

0 notes

Text

Residency in the time of corona, Follow the science, 201129

I have been struggling to articulate my thoughts on COVID for a while. I feel like I have a few main questions like A. What does it mean to “follow the science” and what exactly is “evidence-based medicine?” B. How important is COVID? What I wonder is, how much of our efforts in biomedicine should be re-routed to COVID from ongoing problems like HIV, drug addiction, diabetes? C. How should societal inequalities play into our response to COVID? And D. COVID fatigue. I will try to put some of these ideas together.

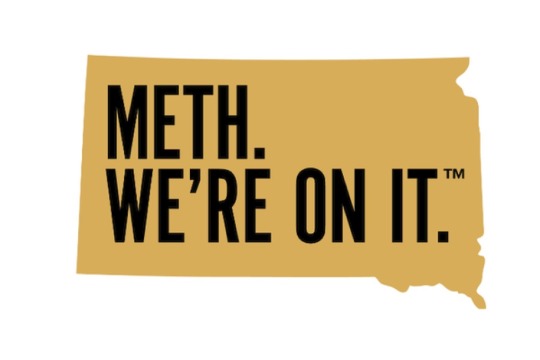

About a year and a half ago I moved to Sioux Falls, South Dakota and I assumed I would live in an anonymous place for a few years. To my surprise, in that year and a half Sioux Falls has made the national news twice. sidenote – Actually now that I think about it there was also this time:

I just googled “meth we’re on it” and I found this and I have to say that I love that someone thought this was such a good idea that it had to be trademarked. Anyways, the first time Sioux Falls was in the news this year was for a COVID superspreading event that happened in a Sioux Falls meat packing plant where a lot of refugees and poor families work. At the time it got a lot of press because it was a concrete example of how the poor were preferentially being killed by COVID. White collar workers with a savings account could afford to stay at home and away from COVID but blue collar workers living paycheck to paycheck had to be out there in the community working. I was worried that this event was just the beginning and it would spread across Sioux Falls. But in fact it didn’t. The outbreak came and went and through the summer COVID was basically a non-issue. In South Dakota we were safe. We didn’t social distance. We never wore masks. And we had no COVID. It gave me a false sense of hope that we were different in South Dakota. Maybe it was the built-in distance of a rural area. Maybe it was the lack of public transportation. Who knows. I didn’t know what it was but I felt like we had dodged a bullet. Turns out I was wrong.

Last month I was on our inpatient team and the hospital is on fire. Obviously I haven’t been a doctor for that long but I’m pretty sure right now is not normal. I think, before last month, I would have been in the camp of people saying that we do not need to be extending excess sympathy to privileged doctors for doing their job but when I was actually in the midst of it was really hard. We had more struggles to send our patients to the ICU because it was so full. We were managing sicker patients with overworked staff. When the hospitals filled up I thought it would hit a plateau but then they started double-rooming patients and then I was going down halls to see patients in rooms I had never been to before. And the patients weren’t only medically complex. I feel like we were ordering more one-to-one babysitters than ever. These are basically staff members that sit in a patient’s room to make sure they behave or at least don’t kill themselves. It’s not an incredibly common occasion to order these one-to-one’s but I swear we had more aggressive and more suicidal patients than I remember seeing. And it’s not even just the extra work or the complex patients that bothers me the most, it’s that there’s this underlying level of stress. It’s keeping up with the constant changes to sick leave policies. It’s those extra couple minutes to put on PPE when I’m already running behind to rounds. It’s when my already quiet voice is further muffled by an N95 and my patients are like what are you even saying. It’s trying to keep up with the latest information when I don’t have the time to know what information to trust. It’s when hospital leadership comes out to tell us that the pandemic is not a big deal. It’s all little things but these are the exact kinds of insidious things that lead to burnout in healthcare professionals. So now Sioux Falls is back in the news for this:

South Dakota is demolishing the hospitalized per capita race. sidenote- My mom told me that South Dakota is even making the news in Japan. My 90 year old grandmother was like wtf is South Dakota doing on the Japan news?? This is probably the first time Japanese people have heard of Sioux Falls. The argument can be made, at least we’re not as bad as New Jersey and New York when they spiked, and certainly that’s not wrong.. but that’s also not right. This probably goes without saying but the size of the hospital infrastructure in South Dakota vs New York City is not the same. When the Sioux Falls hospitals are getting overwhelmed it doesn’t just mean that Sioux Falls suffers. All the complicated patients that typically get transferred in from the surrounding towns are getting backed up into rural community hospitals. I’m trying to get licensed to start moonlighting in one of these rural community hospitals and I can tell you that I would not feel confident taking care of ventilated patients with COVID and PE’s. And sidenote - a couple weeks ago a mask mandate for Sioux Falls got shut down and then approved all in the same week. Everything is happening so fast. I have worries about this mask mandate. I have worries about masks in general because masks has become more than a covering for your face. I do think masks are more or less a good idea and I agree that they probably help prevent COVID but I also think the effect is probably pretty minimal and that the science in support of masks is not exactly a slam dunk. To me the masks thing is representative of a greater problem with this COVID. I know we are supposed to trust the science but I’m just not sure science is made to be used at this sort of pace. Science is cumulative. The way I think about it, science is the kind of thing where one person makes a small discovery, someone else makes another small discovery, then four small discoveries come together to make a medium discovery, but one of those small discoveries turns out not to be reproducible so it takes a while to rethink that medium discovery, and then finally someone in an unrelated field stumbles upon a discovery that gets combined with that medium discovery to create a big discovery like gleevac for CML or reverse transcriptase inhibitors for HIV. If we rush to draw major policy-driving conclusions from one of those small or even medium-level discoveries then we run a major risk of overturning policies, which can get real confusing. I mean think about masks, our public health god Tony Fauci was saying in March that masks are not the end-all and now we are splitting families apart because some people just don’t want to deal with the hassle of wearing a mask. And think of the other aspects of COVID science. We’ve learned that a bunch of stuff doesn’t work (aggressive anti-coagulation, tocilizumab, convalescent plasma), that some stuff actually makes people worse (hydroxychloroquine), and that some stuff that has been shown to work is pretty shaky when attempts have been made to reproduce those findings (decadron, remdesevir). sidenote- should it even be a surprise that steroids may or may not help in a patient with viral ARDS? I sometimes wonder what would have happened if we had just managed these patients as ARDS/sepsis-type patients rather than COVID patients. I think the most unique thing about COVID is its non-effect on kids. That part puzzles me. Anyways, I don’t mean to be a science downer but out of respect for science I just feel we need to be realistic about what it can and cannot do.

See you on the other side,

from ken

0 notes

Note

I have Bipolar/anxiety. I scored very low on MCAT and 130 on my NBME practice test. I've always crammed in med school due to info overload. I really want to be a doctor but I may not be smart enough. I was tempted to blame this on my mental illness but seeing students like you who overcome despite your illness makes me think otherwise. You've been doing well before treatment. I don't know why I've always been struggling. What do you think is the issue? I intend to seek proper treatment soon.

It’s hard to say without having some more information about you but certainly part of the reason for your struggle is likely mental illness. I would definitely encourage you to seek help from a doctor or a therapist, it can really make a huge difference. Happy to talk more via email if you’d like, [email protected].

0 notes

Text

top two favorite patients from intern year

In which I tell you about my two favorite patients from this year. Details of the patients are falsified and loosely based on a true story.

The first is a 66 year old female with a past medical history of congestive heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis secondary to alcohol abuse when younger, type 2 diabetes, and chronic nausea. This was a patient that recently became insured and presented to me after years of neglecting her health. The first day she presented to me her chief complaint was chronic nausea. Following a brief conversation I found that she was also having new onset difficulty breathing and leg swelling, and I newly diagnosed her with heart failure. I remember feeling like an absolute boss for making this new diagnosis. I could tell the attending was impressed. I followed up on this visit with several visits in which I sent her to the cardiologist, we discussed dietary and lifestyle changes she could make to improve her heart function, I read the latest studies and guidelines on heart failure management, we reviewed and re-reviewed the adverse effects of her new heart failure medications. I remember checking off the to-do list of heart failure and seeing the proof in how much better her heart was functioning. I was crushing it. But of course, the story doesn’t end there. Throughout all this time the patient couldn’t care less about her heart failure. All she cared about was her chronic nausea. The chronic nausea that had plagued her for the past year and a half. The chronic nausea that the specialists had discarded as outside their realm. The chronic nausea that was her chief complaint when she she first presented to me. Her husband called me one day to say yes he was happy that her heart failure was improving but what about the nausea that keeps getting pushed to the side? This nausea paralyzed her to the point that she barely left her bed on most days. And this was the first of two crystallizing moments I had during intern year. This is when I realized what makes family medicine physicians unique, that we don’t doctor for an organ or a disease but for the person. The patient’s heart failure was important, but her nausea was what was ruining her humanity. Her personhood. And over the next several months we tried and tried and tried - an ultimately fruitless search for an organic etiology of her nausea, rifling through several traditional and some non-traditional drugs for nausea, and countless frustrating encounters hearing that our latest intervention was a bust. Until one day. One day the patient presented to me and her husband told me, “You know, she hasn’t been nauseated recently. In fact she’s been eating a ton, I’m a little worried about her diabetes.” Holy shit. I couldn’t believe it. I thought I would spend my whole three year residency seeing this patient and not being able to solve her nausea and here she was telling me she was getting up and going for a walk. A short walk, like to the mailbox, but still a walk. She was eating. This was not checking some boxes off of a heart failure list and me telling the patient that she was doing better. This was a real victory. This was her telling me that she felt like herself again. That I had helped her.

The second is not as long. This patient presented to the labor and delivery floor on a day when I was orienting a new resident. The patient was a 23 year old female Gravida 5 Para 1122 at 38 weeks and 1 day gestation who presented for induction of labor for newly diagnosed gestational hypertension. She received pitocin for induction and was progressing slowly. Based on the clinical picture we decided to proceed with breaking the patient’s water. This is one of those procedures that when the other residents do it, or the attendings do it, it looks super easy. This, among many things, was something that I was insecure about all year. How could I dare to think that I could go out into the real world and deliver babies on my own? In fact, just the day prior there was a difficult water breaking that I wasn’t able to do and had to ask the attending for help. Here I was over 370 days into residency and I was still asking for help with this seemingly rudimentary procedure. So flash back to the patient, she needed her water broken so I was trying to talk the intern through the procedure but she wasn’t able to get the bag of water broken. And this was my second crystallizing moment. Just one year prior I was sitting in that same labor and delivery room, I was the sparkly resident being oriented by a highly competent third year resident, trying unsuccessfully to break a patient’s water, and my senior resident getting the job done like it was nothing. I remember feeling like I could never do this. I remember feeling like I was doing patients a disservice. I remember feeling like I should have chosen a different career path. And here I was in that exact same scenario, except I was the senior resident. I stepped in and successfully performed the procedure with the same effort as folding my kids’ clean onesie pajamas. And this was when I realized I had come a long way this year. It was clear that I still had work to do but it was also clear that I could do this.

I write all this to say, yes, intern year was filled with many L’s. So many days when I felt inadequate and found myself comparing myself to other residents, many days when I felt ashamed to admit a mistake or an inability to perform a procedure, but today, on this day when I reflect on this past year, I want to show gratitude to my patients that have taught me so much. Shout out to my patients.

see you on the other side,

from ken

1 note

·

View note

Text

ken explains - NEJM/Lancet-gate

I have to comment on the New England Journal of Medicine/Lancet-gate. The NEJM/Lancet-gate (a link to the news) is about science and fraud and the desire for riches and fame, but it’s about more than that. It’s about George Floyd and Sandra Bland and Walter Scott. Let me explain.

There were two major research findings that were published in NEJM and the Lancet on the topic of medicines that can be used to treat COVID but it turned out these findings are under suspicion of being based on poorly collected or, even, made up data. Think about that. This is middle school level. This is the ultimate version of sparknotes-ing The Great Gatsby, which sidenote - I did. To be fair, I did read it in my 20s. But anyways, these research findings weren’t just published into obscurity. These research findings were significant. Big enough to be published in NEJM and Lancet, powerful enough to make a career in academic medicine, enough to stop ongoing clinical trials, flashy enough to be published in mainstream media.

This drives me crazy. I love science, but more, I respect science. At it’s purest science is beautiful. I love the process of learning about something, coming up with ideas about that thing, then coming up with rigorous ways to test that idea with the hope of bettering the arc of the moral universe. What could be better than using a brain to make the world a better place? But scientists like those in NEJM/Lancet-gate are making a mockery out of science.

There is so much in science that is not science, and the more I see of this bad side of science, the more I feel like ultimately I won’t work in science. What is this bad side of science? This obsessive race of attention. Publishing in sexy journals. Being first. Throwing around publications in the flashiest journals with the biggest and loudest press releases. That’s what science is diminished to. SCIENCE, guys. Science is nothing more than trying to get the most attention and trying to be famous. That’s not right. That can’t be right. I will not stand to live in a world where that is right. sidenote - This is what sours me on big pond. Big ponds are obsessed with this stuff. Publishing in NEJM is currency at these places. Patents on scientific discoveries like CRISPR. And sidenote - y’all, we cannot patent CRISPR. It is not right. It is not fair to the tens and hundreds of scientists that came before Zhang and Doudna and Charpentier. It is not right that some pharmaceutical company is going to profit from the tax dollars and the hours slaved away by grad students and post-docs that created CRISPR. Everyday I become more and more jaded that the best talent, and perhaps more importantly, the best work is done at big ponds. I do acknowledge that some of the best talent does end up at these places. In neurology at Stanford, in pediatrics at Harvard, in radiology at Washington University, whatever it is, but I just can’t bring myself to agree that these institutions and more importantly, the incentives that they create truly allow for the kind of true and meaningful work that can change the arc of the moral universe. sidenote - Speaking of the NEJM and the Lancet, if you peruse these journals recently it’s COVID COVID COVID. COVID is important, yes, but science cannot swoon over the it girl. Science is about the rigorous pursuit of truth. The grind of science cannot be put on hold for a feeble attempt to come up with rapid solutions to COVID. Science does not work like that. It has never worked like that. Science does not work on any person’s time. As an example I reference the greatest translational research accomplishment in history, gleevac or imatinib. On a brief google search the earliest I see the 9:22 chromosome and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) mentioned is 1960. Imatinib, and sidenote - I won’t go into trying to understand the medical and scientific details here, but the point is gleevac is the best example of scientific research leading to a medicine that truly changed the arc of the moral universe. And this medicine, gleevac, was FDA approved in 2001. That is 41 years. That’s how long it takes to go from a bench research finding to a life-changing medicine. 41 years.

That’s why I’m skeptical about this rush to come up with treatments for COVID. Sure, we may come up with some FDA approved treatments that slightly improve the outcomes in patients with COVID but does that really matter? Does that really affect the arc of the moral universe?

We cannot take our eyes off the prize. We cannot stop taking the 1000 mile view. We cannot abandon other NIH funded research in an attempt to find a cure for COVID. This time when it's hard to focus on the RNAs in a worm is the exact time we need to focus on the RNAs in a worm. It is important to fight for what is right but it is more important to keep fighting for what is right when what is right is out of the limelight.

see you on the other side,

from ken

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Residency in the time of corona; 200509

Should we be re-opening society? That seems to be the new hottest COVID topic. As an educated physician-scientist I feel obligated to form some sort of thoughts on this question and I’ve listened to podcasts, read twitter threads, read academic literature, and the only conclusion I’ve reached is that there’s no good conclusion. I wish there was a clear cut answer.

If I had to guess I suspect it would probably go fine to re-open society, especially if it’s done in a controlled manner, is in select locations with less COVID, and continues restrictions on nursing home and hospital visitors, but there’s that small chance that it doesn’t go fine. sidenote - that’s not to mention the question of when and how do you re-open New York City? Do we allow people in and out of New York? Should we be allowing people from NYC into our state? It seems like re-opening societies could work if we self-contain communities and we don’t allow much or any interstate travel but if we’re allowing people from New York or other major COVID hot spots to travel as they please, I feel like it’s just asking for more spread. Anyways, there’s still that small chance COVID causes mass chaos, and if it does it will probably be similar to NYC in that it will be in some major metropolitan area. Everyday since Georgia has re-opened I keep waiting to hear the outbreak exploding and destroying Atlanta and there’s been nothing. I feel like, everyday since I initially started getting worried about this COVID, the media has been pounding this message that it’s going to get worse, and it just hasn’t. Is that just a success of social distancing? Is that a sign that some of the expert COVID predictors predicted wrong? The best conclusion I have is that this virus is still pretty deadly compared to other seasonal viruses, mostly in the elderly and patients with co-morbidities, but I think if there’s one thing that’s clear it’s that it’s not clear which models to trust, and which experts to listen to. sidenote - one question I wish the experts would address is the question of people who have recovered from the virus. At this point there are boatloads of people who tested positive with either no or marginal symptoms who have recovered. Theoretically, these people should be able to barge into COVID positive patient rooms with no gloves, no mask. I mean you could even be naked. And that would be weird, but it wouldn’t be dangerous. These are the people that should be getting deployed to work in healthcare, at nursing homes, at the grocery store. These are the people that should be out in society, mingling, and stimulating the economy.

I’m feeling COVID fatigue and I work in healthcare. I see the impact of COVID and how deadly it can be. Yet, I’m still tired of social distancing, and I just want I to stop. I was vacationing this past week in the state parks of South Dakota and we stayed in a cabin. Next door to us were a bunch of other kids that were playing together and one of them came over to ask my daughter (5 yo) if she could play with them. And I got stuck in this awkward situation of saying we couldn’t play right now, which was kind of true, but it was also kind of a half-truth. We really couldn’t play for the whole time we were there because we were getting out of the house to vacation, but the goal was still to avoid people. I felt weird saying we couldn’t play because we were social distancing. I didn’t want them to think we were weird. It’s weird how feeling weird is such a powerful driver of decisions. In a community where social distancing is growing out of vogue, it’s increasingly harder to stay committed to social distancing even if you feel it’s the right thing to do. It’s hard to see people socializing, hugging, being out in the community without COVID anxiety. And it’s natural to develop a sort of bitterness in that scenario but I think if there’s one lasting thought I have about this COVID is that we cannot allow this to tear us apart. We cannot allow social distancing to become political. We cannot be getting mad at each other for not social distancing enough. We cannot be weirded out that some people are social distancing too much. We cannot be getting on podcasts and tearing down people who disagree with us. We have to be rational. We have to be reasonable. But more than anything else we have to be kind. We have to stay together. They want COVID to tear us apart. To divide us. And we have to fight that urge. No matter how much COVID fatigue abounds.

see you on the other side,

from ken

1 note

·

View note

Text

Residency in the time of corona; 200504

It’s not surprising that New York City would be a hot spot for COVID, but who could have ever imagined that a city in South Dakota would receive the COVID media spotlight? We were just on The Daily for god’s sake. I mean, when’s the last time Sioux Falls was the SF getting the most media attention?

Well, there’s this meat packing plant here in Sioux Falls, South Dakota that employs a lot of low wage workers, where a lot of COVID cases have popped up. At our residency program, we have the honor of caring for many patients from this meat packing plant and I can tell you that we had been worried about this inevitable outbreak for months. A bunch of patients that are broke and motivated to work, with poor healthcare access, crammed together in one building, and going home to jam packed homes. It’s just asking for a social determinants of health disaster. sidenote - before I go further I have to acknowledge that there’s layers to this, it’s complicated, and to be totally honest, I’m not even sure I can blame this meat packing plant. Closing this meat packing plant has prevented farmers from sending their pigs to the meat packing plant, it’s prevented people who really need an income from bringing in paychecks, but it’s also kept people away from a COVID hub. In a time like this it’s hard to know what or whom to trust, but according to what’s out there in the media, this is an absolute disaster. The meat packing plant was considered to be an essential business and forced to stay open, with the downstream effect that it forced many poor workers to work in potentially dangerous conditions, with the report that the company offered a $500 bonus to work in these conditions. I mean, it’s a win win, right? The employer needs people to work, and the employees would love an exatra $500. And who among us hasn’t worked while sick? For whatever reason, in our culture it’s hard to call in sick and put the burden on your coworkers to cover for you. Plus, sometimes it’s hard to know how sick is sick enough to call in sick? If I have a temp of 103F and I’m vomiting every fifteen minutes, that’s pretty obvious. If I have a runny nose with no other symptoms, that’s obvious too. But what if I don’t have a fever but have an occasional cough and I feel kind of nauseated. Am I sick? Am I just a little tired with a dash of seasonal allergies? Regardless of the answer, there’s a lot more pollen in the air when there’s $500 on the line.

sidenote - one thing that makes the setting of South Dakota a little interesting is that while South Dakota is statistically a “homogenous” state, there’s a lot of diversity in South Dakota poverty. There’s this random population of refugees that come to Sioux Falls to escape the war-torn poverty from Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America, there’s the swath of rural farmers with poor healthcare access, and plus there’s the Native American reservations. sidenote within a sidenote - Here’s the racial breakdown of COVID cases in South Dakota. I will not comment and let this graphic speak for itself.