Text

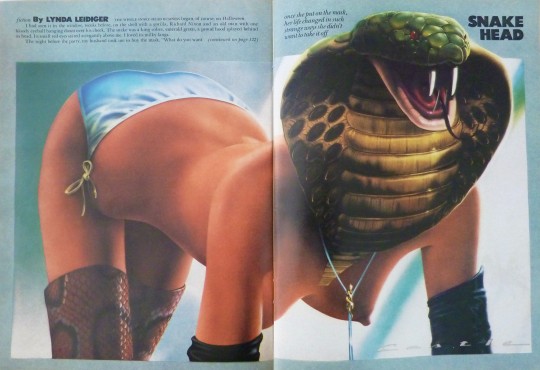

“Snake Head” by Lynda Leidiger

The whole snake head business began, of course, on Halloween.

I had seen it in the window, weeks before, on the shelf with a gorilla, Richard Nixon and an old man with one bloody eyeball hanging down over his cheek. The snake was a king cobra, emerald green, a proud hood splayed behind its head. Its small red eyes stared arrogantly above me. I loved its milky fangs.

The night before the party, my husband took me to buy the mask. “What do you want that for?” he said when he saw it. He was trying on a Jimmy Carter mask and chuckling at himself. The clerk told him they had just sold the last Menachem Begin.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s me.”

I slipped it on. It was very dark and I could hardly see out. My eyes were focused through two small holes in the roof of the cobra’s rubber mouth. It was like tunnel vision, the clerk’s face looming toward me as through a fisheye lens.

“It’s very unique, dear,” she said, squinting at me. “I only had half a dozen of these, and I had to order them back in January. This is the last one.”

Some other customers started to gather around me, pointing and snickering. I made hideous faces at them, testing the mask. They didn’t see.

“I’ll take it,” I said. My voice bellowed in my ears behind the thick rubber walls.

“Isn’t it awfully hot?” my husband said. He peered in at me without meeting my eyes and nodded in satisfaction, as though he had paused at the entrance of a haunted cave and found it empty.

I wore the head all the way home in the car. I could see only straight ahead; palm trees waved like giant feelers at the edge of my vision. I had the odd sensation of being brought home from the hospital. Instead of taking the freeway, my husband drove slowly down Ventura Boulevard all the way from Tarzana to Studio City. Although it was early afternoon and the car window was rolled down, nobody seemed to notice my head. I could tell he was disappointed.

“And they say people in New York are blasé,” he muttered.

For the party, I put on a strapless gown of purple velvet, swarming with seed pearls and rhinestones. I also had black-velvet gloves to my elbows, a rhinestone bracelet and black-patent-leather shoes with straps around my ankles. Finally, I draped a fawn-colored rabbit-fur jacket around me. The jacket felt odd; my husband had given it to me and I had never worn it. The thought of the dead rabbits was still faintly sickening.

My cobra eyes stared at me from the mirror. A golden reptile throat rose from my shoulders. I was magnificent.

“It’s a shame you don’t have some green body paint,” my husband said. He was angry because he wanted to go as a gypsy and I wouldn’t let him take my violin. He thought he had a right to it because I hadn’t played in two years. He grumbled as a cut a hole in my throat so I could drink through a straw without taking off the head.

It turned out to be one of those Hollywood parties. I’m not sure how we were invited, but we went because my husband thought he might make some connections. Someone told him Ralph Bakshi might be there. A Doberman in a feather boa lunged for me at the door, barking and frothing. Fidel Castro slapped the dog’s snout until it was quiet, and handed me a joint.

“Charmed, Fidel, I’m Joan Crawford,” I said, holding out my velvet hand to him. He looked pleased to be recognized. Nearly everyone laughed. My husband beamed; he hadn’t been so proud of me in years. I held the joint to my throat and watched in the mirror as the smoke slid out over my black tongue.

We went out onto the patio and stood, smoking, under the cardboard skeletons hanging from the eucalyptus trees. Their feet scraped loudly against my head. I could tell that Ralph Bakshi wasn’t going to show up there. I got myself a glass of wine punch.

“Hey, what do you look like under that mask?” some guy asked. He wore a tweed cap and there were several pipes in his pockets. I tried to decide whether or not the pinkish-purple blotches had been painted on his cheeks. “I bet under that mask you got blonde hair. Am I right? The coat’s the tip-off; if you had dark hair, you wouldn’t wear a coat that color.”

“If she had, like, black hair, the contrast would be too much,” someone else agreed. He was an actor from Phoenix. He told us several times that he had just arrived in L.A. yesterday with two dollars and eight cents in his pocket. His shoes didn’t match and his eyebrows were drawn so that one went up and the other down.

“I bet she’s got blue eyes, or maybe hazel, and high cheekbones. And very soft skin,” the guy with the pipes said suggestively. His acne glowed eerily under the patio floodlights.

My husband smirked, pleased.

“Just pretend I’m not here,” I said, and had another hit.

A girl with pigtails and white knee socks came bouncing out of the house. Under one arm she carried a cloth doll in a bonnet. “I heard there was something to smoke out here. I haven’t moved so fast all night.” She giggled.

“It’s harsh,” the actor said, passing her the joint.

“Harsh. It’s nice to hear harsh. I mean, people say raspy. Raspy and dusted!” She tossed her pigtails and took the joint in long, noisy gasps. “It’s flippy. Hey, you’re a soldier,” she said to Fidel.

He took the cigar out of his mouth disgustedly. “Exactly what are you supposed to be?” he said.

“I’m four years old,” she said, cradling the doll.

“I’m twenty-one, going on a thousand.” The guy with the pipes kept trying to look in at me, but he was having a hard time standing up. I was having a hard time trying to figure out why no one seemed to have come in costume.

“God, aren’t there any potato chips? Raw vegetables give me ulcers,” the actor said and wandered off.

The guy with the pipes poked the girl’s doll. “That Raggedy Ann?”

The four-year-old scowled, crinkling her painted freckles. “This is Holly Hobbie. Her friends call her Hobbie; I mean, Holly.” She dissolved in giggles.

I found that I could push pretzel sticks through my throat.

“I want to show you something,” Fidel whispered. He led me up to his room. Over his bed was a huge oil painting of a Venetian canal. He told me had painted it himself in 20 hours. It wasn’t badly done at all. Somehow, he had put a small light behind it so there was a sun in the sky, which he could make brighter or dimmer. The sky was a kind of faded amber color and the crumbling buildings were dried caramel. He turned the sun low for me. “I knew you’d like Venice,” he said, fingering my purple velvet.

Just then, the four-year-old came in. “Wow. What color is it?” she said.

Fidel let go of my dress and put the cigar back in his mouth. He looked as though it didn’t taste particularly good. “There are twenty-two colors in it,” he said. “I have them written underneath.”

The four-year-old bent over him to get closer to the painting. It was getting hot inside the head; I felt like going out again. As I left, I heard her telling Fidel that she could see a little blue. I met the Doberman on the stairs. He quietly showed me his teeth but didn’t bark.

My husband scarcely took his eyes off me all night. He devotedly brought me carrot sticks and slivers of zucchini to push through my throat. Once or twice he pressed against me behind the punch bowl.

Two more people came to the party, a cop and his girlfriend. They came as each other. The guy who thought I was a blonde had taken over the stereo and was playing two lines of a Dylan song over and over again.

“Oh, Momma, can this really be the end?” he sang mournfully, waving one of his pipes.

“Oh, let’s go,” my husband said. “Everybody here is trying to break into commercials.”

As we left, the guy stopped singing Dylan to whisper to me, “I’ve voted you beauty queen of the night.”

I turned to glare at him, but the snake head stared straight ahead, haughty and indifferent, as we swept past.

At home, I took off the purple dress and touched the emerald scales of my face.

“Leave your shoes on,” my husband said hoarsely.

He pushed me onto the bed, grabbing my breasts and pulling himself into me, a climber gaining a momentary hold on an impossible cliff. I dug my nails into the meat of his broad back and spurred him on with my shiny heels. He came within seconds, as always.

“That was wonderful,” I said, as always. I touched the cobra head gratefully and cried until my tears welded the rubber to my skin.

I wore the snake head to work on Monday, with a new dress in a soft, wine-colored material that clung to me. I felt sleek and shapely, but it was the cobra head that made me feel beautiful.

“What are you supposed to be?” Rosemary said. She was a stupid, unhappy woman, just smart enough to be perpetually suspicious that people were making fun of her. She had been a secretary with the company for 28 years.

“Happy Halloween,” I said, sitting at my desk and uncovering my typewriter.

Rosemary frowned at me. “You watch it,” she said. “Mr. March said just the other day he thought you had some kind of rebellious streak. But I stuck up for you, I said you were maturing. You’re going to ruin me,” she hissed.

There was a stack of work in my basket. I crumpled the vinyl cover of my IBM and shoved it into a drawer. “I’m getting a cup of coffee,” I said.

Going down the hall to the coffee machine, I saw my lover. He was lean, forest-eyed, wheat-haired. Seeing him always took my breath away, made me weak in the knees. I was a fool, an embarrassment to myself.

He smiled at me. His eyes slid up the forked tongue and found me right away. He shook his head. He thought I was beautiful.

Safe within my rubber fortress, my slack idiot’s face melted for him. I have known you 100,000 years; we were dinosaurs together, I told him soundlessly.

Mr. March saw us in the hall. He bent toward me, trying to look down my dress. “Don’t we look yummy today?” he leered, looking to my lover for agreement, but he was gone.

“Do we?” Fuck yourself in the ass, I mouthed gloriously.

His lean brown vulture’s head bent farther toward me. “Who are you supposed to be?” he said. His wrinkled tie dangled obscenely outside his vest.

“I’m supposed to be a secretary,” I said.

Still bent over, he said, “Why are you afraid of me?”

“I’m not afraid of you.” I hate you, I said.

His face constricted with pretended concern. “Why don’t you open up to me?” he said, very low. “You mustn’t be afraid. You won’t get the reaction you expect. Think about that.” He wagged a finger at me, brushing my breast.

“I’ll think about it.” You asshole, I said.

When I got back to my desk with my coffee and my straw, Rosemary was typing furiously. “You’re cute” was all she would say.

My lover came by to take me to lunch. We went to his apartment. He is a writer; his four unpublished novels, neatly bound, stand next to his bed. They are all about a woman he loved in Paris eight years ago. He does not expect to love again.

The early afternoon sun, filtering weakly through the vines, dappled us like lepers. He stroked my proud hood with one hand as he undid my dress. I writhed beneath him, then over him, my hidden face contorted into molten curves of longing. I felt my lips curl past my teeth; sweat drizzled down my cheeks. There was a downpour in my head, dim memories of an ancient sea.

Afterward, he gave me some Perrier to sip through a straw. He put on an old record and sang to me, his voice flat and husky as the November wind. He was wishing he was in Paris.

I cut tiny slits between the scales to make the head more comfortable and stopped wearing make-up. I took off the snake head for a few minutes every night and washed my face in the dark bathroom. Once I turned on all the light and nearly screamed. The head in the mirror was pale, grotesquely small. The face quivered stupidly, a weak, pitiable, unsafe face. A face that I had tolerated despite nearly 30 years of consistent betrayals. Of its own will, it would blush and snarl and yawn and weep and look alternately sad and foolish. It had no interest in protecting me. I had given it many chances, I thought, as I put the snake head back on. It felt so good.

After I had worn the head for a week, Mr. March called me into his office. He liked to sail and there were models all over his desk and credenza. “Don’t you think you’re carrying this thing too far?” he said, staring in at where he thought I was.

I said nothing. A cobra says nothing.

“You’re not in college anymore. This kind of prank won’t go over here. You’ve got to think of your career,” he said. “You’re a bright girl, but you’ve got to start watching your step. We can’t have this. Besides, it must get terribly hot in that thing,” he added hopefully.

I reminded him that I was always on time, that i was the best typist in the office, that my work was always in compliance with company standards. I casually mentioned discrimination and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which was already handling several suits against the company.

He blanched under his Sunday-sailor’s tan, then tried to look hurt. “I don’t know why you're afraid of me.”

I left him jabbing his pen into the rigging of an old whaler.

Drinking all my meals through a straw was beginning to make me thin. For the first time in years, I liked the way I looked. My lover ran his tongue along the clean blades of my hipbones and pressed his face against my flat belly. He murmured that he thought his French was beginning to come back.

He pureed oysters for me in the blender and made me duckling à l’orange, frogs’ legs provençale, poached salmon with chestnuts. He sauteed tiny carrots and crumbled dillweed into the melted butter. He tenderly fed his creations into the blender and I drank them with a straw.

My husband complained, “Your tits are too small.” He said it was like screwing on box springs without a mattress. He had lost his hold. He bruised the span of his chest against my knees night after night. He never wanted me to take off the snake head.

Sometimes, after he was asleep, I’d sneak into the kitchen and put something in the blender for myself, a taco or a bowl of Cheerios, and drink it through my cold sleek snake throat. Once I stole a page of my lover’s latest manuscript and tried to drink it, but Paris was a pulpy gray paste that stuck in the straw and had to be scraped out of the blender.

I began playing the violin again. I crouched in the closet and played while my husband slept. I began memorizing arias from Bach’s Passion According to Saint Matthew and singing along quietly in melancholy German. I cried happily in the dark, under the coats.

After a while, Mr. March wouldn’t even look at me, no matter what kind of dress I wore. I licked my lips at him invisibly as she shrank against the wall, clutching his attaché case, his bald brown head smooth with revulsion.

Rosemary no longer confided what she and Mr. March said about me. They went to long lunches together; she’d come back flushed and self-righteous.

She rarely spoke to me. One day she said fiercely, “Why don’t you just go home and have some kids? Or are you afraid they’ll hatch?” Her sneer was so ignorant that it needed no reply.

My husband bought me an imitation-leather bra and garter belt. He went to Frederick’s of Hollywood, I suppose. He also bought me some absurdly pointed imitation-snakeskin boots. Luckily, I never had to walk in them. It must be like making love to a La-Z-Boy recliner, I thought, smiling while he grunted and battered himself against my Naugahyde thighs.

One night, when he was through, he told me about a bad dream he’d had.

“You burned the house down,” he said. “You meant to do it. You said we could only take a few things, to make it look like an accident. Then you sprinkled gasoline around the house and we lit it. I helped you.” He shook his head slowly and he said again, “I helped you.”

“Why did I do it?” I said.

He looked at me, his eyes searching the cobra cavern. He looked puzzled, then annoyed and sullen, like someone trying to scrape mayonnaise out of an empty jar that he could have sworn was full. “I don’t know,” he said. “It wasn’t in the dream.” Moments later, he was asleep.

A few nights after that, he got up for a glass of water and heard me in the closet. I was playing Come, Sweet Death, sobbing blissfully. He grabbed my arm and yanked me out into the light. He was shaking. Slowly he reached for me and, with both hands, tore off my head and ripped it up the back. He looked at it for a moment, lying in his hands. Then he threw it into the bathtub and started lighting matches. The scales began to smoke and melt, oozing across the pink porcelain. The smell was nauseating.

He carefully turned over the head so that I could see the emerald hood darken and fall away. The small red cobra eyes rolled upward in despair, the soft fangs flowed like marshmallow cream over the forked hot tar tongue. I pressed my violin into my chest until the strings groaned.

The room was filled with fetid black smoke. My husband was crying, too, tears cutting grimy ditches through the soot on his face. For a long time, he watched the feeble, smoldering thing that had been the snake head; he couldn’t stand to look at me. Finally, he got himself a glass of water and went back to bed.

0 notes

Text

Frail Shrines

Our first title for 2017 is Frail Shrines

Get it here: https://gumroad.com/l/AynqL

0 notes