Photo

Tactical Anger and Its Power: Words and Actions in the Age of ACT UP

submitted essay for my Youth in Revolt course in the Global Liberal Studies program at NYU in Spring 2018

The 1988 photo shows only the jacket-clad torso of a young man. Careful letters surrounding the upended pink triangle on his back read, “If I Die of AIDS, Forget Burial, Just Drop My Body on the Steps of the FDA.” In context we know that the jacket and its wearer were part of a protest by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). The man in the photo, artist David Wojnarowicz, died less than four years later of the disease he was protesting. Today the photo is historic, used in remembrances of the AIDS epidemic and referenced by high schoolers in their new fight against gun control. The CDC reports that between 1981 and 1992 over 200,000 people in the United States were infected with the disease. Within those years, the CDC places the percentage of those killed by AIDS at about 89 percent. A slew of activist groups arose out of this urgency, working to push the US government to address the epidemic. While certainly not the first, ACT UP is perhaps the most well-known.

This essay seeks to examine how meaningful, focused anger was used as a positive force by ACT UP members during the peak years of their activism. Michel Foucault and Jack Halberstam’s approaches to power and its structure in society are particularly crucial for understanding ACT UP’s radical, anti-capitalist approach in their fight against the violent ignorance of the federal government and the incorrect narrative of the disease perpetuated by the news media. In addition to repositioning the connotation of AIDS as a solely gay male disease, ACT UP used their anger and grief to turn loss into activism and force the United States government to acknowledge and act on the epidemic.

The first organized ACT UP protests began in March of 1987 on Wall Street in New York City “the financial center of the world, to protest the profiteering of pharmaceutical companies.” The organization, which had formed just weeks earlier made enough of a statement to gain attention from The New York Times and the FDA. The act of civil disobedience meant arrests for seventeen members.

From the beginning, ACT UP established itself in direct opposition to the capitalistic principles of the pharmaceutical industry. In The Queer Art of Failure, Jack Halberstam juxtaposes the “heteronormative” and “subordinate, queer, or counter-hegemonic” concepts of success. He argues that the heteronormative construction of success values “capital accumulation,” while the queer, or non-dominant construction is associated with failure because of its focus on “non-conformity, anti-capitalist practices, [and] non-reproductive lifestyles.” Media coverage of the disease – and the activists fighting it – focused primarily on the idea that AIDS was a disease that solely affected gay men. The headline for the New York Times coverage of the Wall Street protest read, “Homosexuals Arrested at AIDS Drug Protest.” In their outreach, however, ACT UP worked to correct the narrative and raise awareness about the facts of the disease.

The Women’s Committee within ACT UP distributed information that specifically addressed the existence of the disease within the Lesbian community in addition to continuing to provide key information about the epidemic as a whole. One flyer, titled “AIDS: A Lesbian Issue?” breaks down the ways that women can contract AIDS. The document uses inclusive language, such as the continued use of the “we” pronoun. Furthermore, the document disrupts the notion of “gold star lesbianism” and refrains from shaming IV drug users. One section of the document reads, “We have to take talking about sex and our sexual history out of the closet. We have to trust and support each other enough to talk about sex and safer sex. Lesbians are at risk because we have sex.” The document asks its readers to get involved, citing statistics about AIDS deaths and drawing attention to the disproportional affect the disease has on people of color. This document, and a similar one aimed at readers of Cosmopolitan, both express dissatisfaction at mainstream coverage of AIDS and encourage involvement from women readers.

These women-specific flyers also highlight the disparity of AIDS research, citing the lack of “official statistics” and the perpetuation of violence against those in the queer community. This specific ACT UP campaign seeks to raise awareness within a broader group. In The History of Sexuality, Foucault writes that “there is a plurality of resistances, each of them a special case.” The Women’s Committee of ACT UP modified their tactics when their target audience broadened. They pinpoint specifically why AIDS is also a women’s issue and call for involvement to “protect ourselves against violence” and “fight for our relationships, for our community and civil rights, for control over our bodies, our health, our sexuality, our lives.” The expansion of outreach focused on the vulnerabilities of a specific, at-risk group that had the power to mobilize and join forces with those already participating in the movement.

This focus on restructuring the narrative also required a careful approach to media outreach. Internal documents distributed to ACT UP members show the groups targeted approach to interviews, both in paper and on television. Ann Northrop, a journalist and activist, created a document called “How to Manipulate the News Media.” The numbered list gives members precise advice on how to handle being interviewed about the cause. This particular pamphlet does not delve into facts about the cause but rather focuses specifically on how knowledgeable activists can best serve ACT UP by becoming critically thinking spokespeople.

While the title is eye-catching and seems intent on provocation, the actual contents of the document are straightforward and realistic. The first point of the document, “Listen Before You Talk,” urges members to note the way control works in media coverage. “The most important thing you can do is control the editorial point of view of the whole story. To do this, you must interview the interviewer.” Later the document acknowledges that journalists think that interviewees “are crazy,” because they “understand how little control the interviewee has, and how exploitative the whole process is. So reporters start out with some basic contempt for the people they interview.”

Michel Foucault writes extensively about power relations, arguing that “there is no power that is exercised without a series of aims and objectives.” The news media document demonstrates ACT UP’s clear cognizance of the roles at play, even in a relationship as seemingly simple as journalist and subject. Northrop is clear that the journalist (and to a greater extent the media company) maintains power over the spokesperson. However, the stakes for which the journalist plays are comparably lower than those members of ACT UP intending to speak out and educate. The document aims to earn “good” press for ACT UP in the form of a uniform, polite approach. Additionally, Northrop’s prior experience as a journalist mean that her tips come from “inside” of the trade. The power dynamics at play here are not simply hierarchical. Foucault writes against the notion of “strictly relational character” in power relationships. Instead, he argues that they “[depend] on a multiplicity of points of resistance: these play the role of adversary, target, support, or handle.”

In this case, ACT UP showed a clear regard for the value of media publicity. However, as previously discussed, much of the media distributed about the nature of AIDS, at-risk populations, and activist work was incorrect. Northrop’s document shows the group’s clear intent; ACT UP’s “manipulation” of the news media was really a push toward fair, factual coverage and another step toward finding proper treatment and care for those with the disease.

Another crucial aspect of ACT UP was the vocal nature of their protests. These “actions” perhaps best display the way ACT UP activists targeted their anger toward tangible political change. In demonstrations, the group often used the now iconic chant “ACT UP, Fight Back, Fight Aids!” The shorter phrase, “fight back” was used in a number of other chants. In this primary chant, the word fight has a double meaning: one in reference to how bodies tackle illness and the other perhaps more aggressively to the violence committed by the passivity of the government.

ACT UP expressed their disdain for government officials and their ignorance and intolerance about AIDS in several ways. The vocal, public, and often visceral nature of ACT UP protests gained greater attention and in turn allowed AIDS activists to make demands about their cause. The first protest on Wall Street specifically targeted the FDA and President Reagan. The list of demands called for immediate release of potentially lifesaving drugs, while simultaneously scolding Reagan and the pharmaceutical industry. “Curb your greed!” one demand reads. The end of the list declares, “President Regan, nobody is in charge!” While this protest was focused on two main subjects, ACT UP did not limit their criticism to a specific party or industry. Lists of chants and poster slogans delineate between “general,” “Democrat,” and “Republican.”

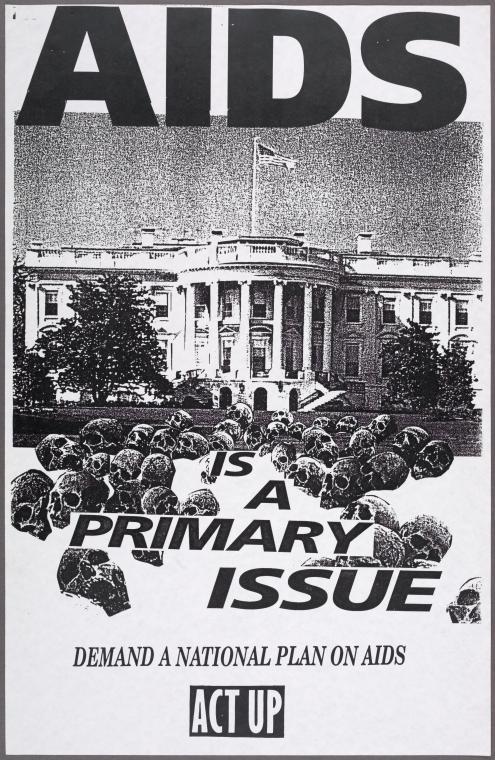

Protestors did not steer clear of AIDS deaths, instead emphasizing the rising death toll through poster art and chants. A chant against Reagan declared, “Reagan, Reagan you can’t hide! We all know its genocide!” Similarly, a print poster depicted skulls lining the way up to the front of the White House. The messages directed specifically at Democrats are less visceral; posters aimed at Democrats like Dukakis and Gore carry messages like “We vote too!” and “We are watching you!” Another poster bears the message “Our vote is a weapon we are prepared to use.” These messages establish ACT UP as important demographics within the voting population. Rather than succumb to the “dominant logics of power and discipline,” these political statements serve as assertions of control within the paradigm of heteronormativity that Halberstam sets forth.

ACT UP did not stop at artistic depictions of AIDS’ death toll. The group also staged “political funerals,” including putting ashes of AIDS victims on the lawn of the White House and bringing the open coffin of Mark Lowe Fisher to the headquarters of the Republican National Committee in New York in 1992. Prior to his death, Fisher wrote about his wish for such a funeral:

Death takes place behind closed doors and is removed from reality, from the living. I want to show the reality of my death, to display my body in public… I want my death to be as strong a statement as my life continues to be. I want my own funeral to be fierce and defiant, to make the public statement that my death from AIDS is a form of political assassination. We are taking this action out of love and rage.

Fisher and his fellow activists were aware of – and fully intended – the shock factor in political funerals. His funeral was one death in hundreds of thousands in the United States alone from AIDS. The mobilization of grief in ACT UP protests, in combination with the group’s ability to create tactical approaches to change policy and raise awareness propelled the movement forward. Political funerals also subvert the idea of death as failure or finality. Halberstam writes that “capitalist logic casts the homosexuals as inauthentic and unreal, as incapable of proper love.” The political funerals, as Fisher described, are out in fact out of love – and rage. The authentic, heartfelt, and brutal emotion behind actions as intense as political funerals only serve to underscore the group’s dedication to their loved ones and community and their fight for legitimacy.

ACT UP’s protests were rooted in grief and anger, as well as an urgent desire to restructure the narrative around AIDS. In their oral history project, ACT UP members describe forming the group to “turn anger, fear, grief into action.” The group used their own emotions constructively, and worked to shift the dynamics of power present in both the federal government and news media. The movement sought to reshape conversation around the disease, raise awareness within the LGBT community and outside, and secure treatment. The devastating trauma of the AIDS epidemic and the memory of the federal government’s neglect remain, but so do groups like ACT UP. The group’s mobilization turned desperation into real, effective change that is still visible in activist work done today.

1 “Political Funerals.” ACT UP New York, 1995

2 ”HIV and AIDS --- United States, 1981--2000.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

3 “ACT UP Capsule History.” ACT UP New York.

4 “ACT UP Capsule History.” ACT UP New York.

5 Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press, 2011 (182).

6 A term used to describe a lesbian who has never had sex with a man; This document and the group in particular work to fight the transphobic and otherwise shaming nature of this term and association.

7 “Method.” The History of Sexuality, by Michel Foucault, Crane Library at the University of British Columbia, 2009 (514).

8 Northrop, Ann. How to Manipulate the News Media. How to Manipulate the News Media, ACT UP .

9 Foucault 514.

10 Foucault 515.

11 Halberstam 181.

12 “Political Funerals.”

13 Halberstam 185.

14 “The Tactics of Early Act UP.” ACT UP, ACT UP New York.

Works Cited

ACT UP Capsule History.” ACT UP New York.

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press, 2011.

“HIV and AIDS --- United States, 1981--2000.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "AIDS is a primary issue. Demand a national plan on AIDS." New York Public Library Digital Collections.

“Method.” The History of Sexuality, by Michel Foucault, Crane Library at the University of British Columbia, 2009.

Northrop, Ann. How to Manipulate the News Media. How to Manipulate the News Media, ACT UP.

“Political Funerals.” ACT UP New York, 1995.

“The Tactics of Early Act UP.” ACT UP, ACT UP New York.

0 notes

Photo

NYU Multimedia: The Fight for Elizabeth St Garden

0 notes

Photo

NYU Local: Professor Found Responsible for Sexual Harassment Will Teach A Course This Fall

0 notes

Photo

NYU Local: NYU Trustees Have Ties to Aramark

0 notes