Text

Community, History, and Transportation

Jane Jacobs talks a lot about community and what that means. This idea of the street is such an important part of Sunset Park life. There are always groups of people hanging out in front of their stoops, on the sidewalk, and in the parks. In the summer, the back yards fill with gatherings and music.

However, the community in Sunset Park has gone through many iterations over the years. Starting with Native Americans, then the Dutch and English from the 1600s through the 1800s. In the 1800s, immigrants from Ireland, Poland, and Norway filled up the neighborhood. In the early 1900s, the shipping industry, which sustained the workers in Sunset Park bagan to die out and the neighborhood became Puerto Rican. Over time, a mix of Latin American immigrants filled the neighborhood with an influx of Chinese in the late 1900s. Today, we see the neighborhood shifting again through gentrification. The problem, there are few affordable places for New Yorkers to live on a working salary. For more information, check out: https://www.nywomenimmigrants.org/neighborhood-history-sunset-park-brooklyn/

And the mechanisms of gentrification are often surprising and complex, from housing to transportation. Here we will focus on traffic safety and biking.

Over the years I have lived in Sunset Park, we have several large roads running through our neighborhood, including 3rd and 4th avenues, which are used heavily by commuters; they almost feel like highways at times. Crossing these routes as pedestrians or cycling on them is very dangerous and traffic deaths of pedestrians and cyclists have been reported frequently. Over the years, little has been done to address this issue.

Recently, there was a community meeting about putting in a bike path that runs down 4th Avenue. This would mean that bicycle commuting to and from Sunset Park would become significantly safer. Since many Latinx bike to work, this could be good for the Latinx community.

However, at the community meeting, Uprose, an important grassroots community organization was adamantly opposed to the bike lane (See here for more information). At first, I didn’t understand why, but I was told, unofficially, that it was because it is also highly desirable to gentrifiers who are already flowing into the neighborhood and raising housing prices, food prices, and prices for basic commodities. Those who attended the meeting were mostly white and did not represent the community anywhere near fully. Also, I find it frustrating that, after years of ignoring traffic safety issues, the city was willing to invest in bike lanes, something that so many gentrifiers want.

📷

Source

Also, the project required the narrowing of the medians running down the center of the many lanes of 4th Avenue. Since the bike lanes were put in, it is clear that this does, in fact, put families at risk as a parent with small children will most likely not make it across the street in one light. They are now stuck on these narrow medians as cars whiz by.

Another issue with cycling is that tickets for cycling violations are disproportionately given to black and brown cyclists. According to Streetsblog, 33% of those ticketed were described by the police as ‘Hispanic,’ but only 29.1% of New Yorkers are Latinx according to the 2019 Census . 51% of those receiving citations were described by the police as black men, but only 23.1% of New Yorkers are Black.

On the one hand, bicycle lanes seem like they would create more eyes on the street and community and less dangerous car traffic. On the other hand, it would mean shrinking the size of the medians on 4th Avenue and stranding large families and others in the middle of the avenue, more vulnerable to cars. More importantly, the accompanying gentrification threatens the whole balance of our neighborhood and the community ties that have been built over many years.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spanish Language, Dual Language Education, and Latinx Culture; The ties that bind

It's really sad for me that in the United States the Latino community is losing its culture and language, especially among kids born here - a lot of them can't even speak our language. - Romeo Santos

This sentiment is not uncommon and yet, it is juxtaposed against the urgency that immigrant families feel for their children to learn English. Further, in the 1990s and early 2000s, there was an intense English only sentiment amongst many Americans, embodied in Proposition 227 in California, which literacy outlawed bilingual education in the public schools there for some 18 years, until it was repealed by Proposition 58 in 2016. At that time, people often expressed fears that children who came to the public schools speaking Spanish (or any language other than English) would grow up unable to speak English and unable to fully participate in the American Democracy. And yes, like in the quote, it was a fear not just of the Spanish language, but of the growing Latinx population in the United States (the examples of bilingual education nearly always were Spanish language programs).

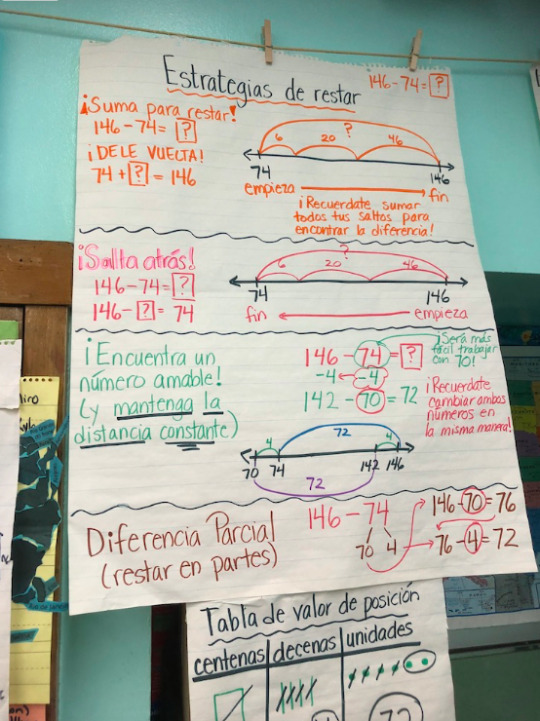

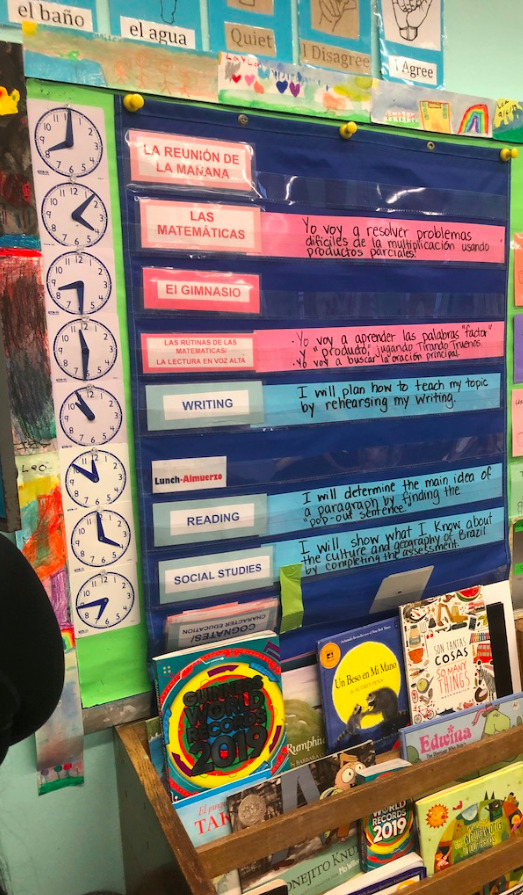

By the year 2003, when I began to teach in a Dual Language program here in Sunset Park, the remnants of that anti-bilingual, anti-Spanish movement were still felt. However, Dual Language programs and a growing appreciation for bilingualism were beginning to bloom. I taught in one of a handful of Dual Language (Spanish-English) programs in New York City at that time, P.S, 24 in Sunset Park.

At P.S. 24, I interviewed Australia Fernandez, a long time Dual Language educator in New York. At the time, she was our Dual Language Coordinator and a powerful advocate for Dual Language education. I recently interviewed her to gain perspective on why she believes so strongly in Dual Language Education and how it has changed. You can listen to the full interview here.

Over the years, Australia has expressed to me a belief that Dual Language programs allow newly arriving Latinx kids to feel safe and welcome. Given the profound connection between language and culture, that is no surprise. Yes, being able to communicate is paramount to a child’s sense of belonging. And, that language is also a connection to our history, our families, and our heart.

Born in the Dominican Republic, Australia moved to Sunset Park in 1998. She was part of many waves of Dominicans who came to New York in what she describes as the chaos of the aftermath of the 31 year Trujillo dictatorship.

“If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart” – Nelson Mandela

“Language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going.” -Rita Mae Brown

When she arrived in Sunset Park, Australia was reunited with her mother after many years of separation and the experience was jarring. She describes being put into an English only class and how degrading it felt to her to be treated like a small child by her teacher after feeling so academically competent in the Dominican Republic. Fortunately, she was later transferred to a bilingual class and that experience was rich and exciting. Being able to learn and engage in Spanish made her feel safe. Her memories and the way she tells her story really help to walk in her shoes and see how meaningful it was for her to be able to experience school in both Spanish and English. The access to Spanish made English exciting and challenging, instead of alienating. As a teacher, I see this over and over in my students and their families as they participate in my Dual Language program.

Years later, Australia fell into Dual Language education. She taught for many years and she and other long time dual language teachers tell stories of school where Spanish was not welcome. Once Sunset Park principal was said to prohibit Spanish speaking in the school office. Other educators tell stories of teaching students in Spanish behind the backs of administrators. This is hard to imagine today, when Dual Language programs are all the rage and Dual Language education is growing stronger every day among Latinx and non-Latinx families alike.

After 18 years of teaching in Dual Language programs in New York, I now find it ironic that the public fear was that children would never learn English, when in fact the opposite has been my observed, lived experience. In fact, over 18 years, never once have I seen a child fail to learn English. However, I have seen numerous children lose their Spanish, even as early as 2nd or 3rd grade, finding themselves unable to communicate fully with their immigrant parents. In our urgency to ensure that children learn English, we are sometimes taking away something critical to their well being and success - their connection to their parents and family. Even more ironically, there is endless research that shows that being dual language programs lead to more academic success for students (English or Spanish dominant) than a monolingual education.

More importantly, the tide has been turning and there is more appreciation today for the contributions of Latinx and Spanish speakers in the United States. Being bilingual, bicultural, and culturally proficient is viewed as an asset. Well, at least in our world here in New York City. Despite Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” rhetoric and despite the fact that there is still a long way to go, the change in New York City around Dual Language Education has been great. This benefits my students and all New Yorkers.

To speak a language is to take on a world, a culture. - Franz Fanon

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reinaldo Arenas: Writing as Dissidence

Undeniably, Latinx immigrants have been a major force shaping New York’s world renowned art and culture.There are so many groundbreaking figures, from Mexican artists like Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera (and other muralists) to Puerto Rican writers like Junot Díaz, Dominican poet Elizabeth Acevedo. So many Latinx artists and authors have made their mark on New York, either growing up here, visiting, or living in New York for a brief time.

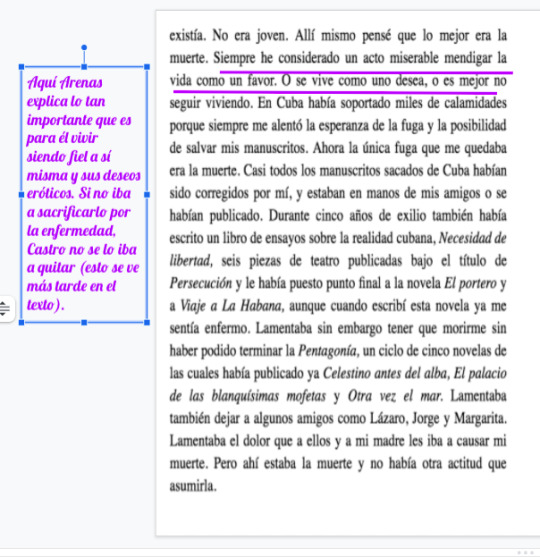

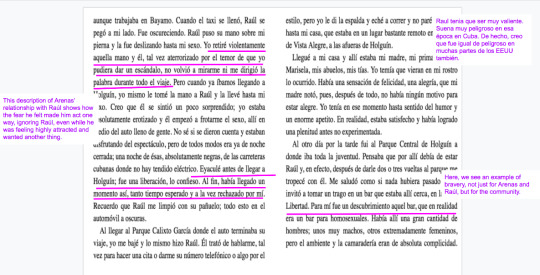

Reinaldo Arenas is a part of this proud tradition. He wrote his book in the late 1980s as he is dying of terminal cancer. It is clear that he wants to document the story of his life before he dies, which he does in a collection of mini personal narratives in chronological order. It is also clear that a primary goal is to show that Castro’s Cuba was a dictatorship, specifically detailing the countless oppressions of homosexuals and his journey to his true self in the face of that oppression.

For Arenas, living honestly and openly as a homosexual was everything to him. In the introduction to his book, he talks about being too sick to be seen as a sexual being in the men’s bathroom and how he doesn’t see the point of living, if he can’t (see annotations to the left). It is clear that a major purpose of this book is to show, before he dies, that Castro is a dictator. He shows this through the stories of his life, documenting his journey from Batista’s rule to Castro’s, including his own participation in the Cuban revolution.

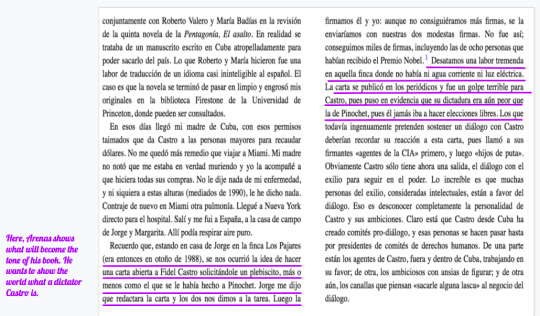

As the introduction progresses, he begins to give evidence of Castro as a dictator.

So many Latin American authors write about the United States as a capitalist, oppressive force in the region (e.g., Ruben Dario and Jose Martí). However, Arenas seems to gloss over the U.S. role in Cuba. In his early chapters, Arenas describes the incredible poverty he endured. An article in the New York Times describes United States policy as a major cause for that poverty. Arenas, on the other hand, almost describes the poverty as inevitable (maybe even romanticizing it a bit). He rarely if ever mentions the U.S. or Batista (the dictator at the time). This is in stark contrast to the way he constantly invokes Castro’s name and describes his oppressive and dishonest behaviors later in the text, even dedicating an entire chapter to his name.

It is also interesting that he describes how Castro somewhat accidentally became the leader of Cuba, when Batista unexpectedly stepped down in 1959. A New York Times article corroborates that account. However, The Times article also describes Castro’s many years of fighting against Batista and his oppressive regime as well (including 20 years in prison). This history is omitted from Arenas' book.

What is also interesting, is that Arenas neglects to address the incredible pressure that Castro was under from the United States and how that pressure, again according to that same article, pushed Castro to seek refuge in communism and the Soviet Union.

As a self identified homosexual, who experienced so much oppression, Arenas felt compelled to fight back in so many ways. In a sense, being homosexual forces so many to either repress themselves or to become dissidents. As a writer, Arenas follows the tradition of Ruben Dario, Jose Marti, and so many others using his writing as a powerful tool to fight oppression.

This book is written in a personal tone that drew me into Arenas’ stories and helped me to see how brutal and hypocritical life was for him in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. This repression is corroborated in this New York Times article of two other Cubans, who, like Arenas, fled on the Marieli. The atmosphere of constant fear and the endless stories of hidden sexuality, reeducation camps and brutal mistreatment of homosexuals are heartbreaking and it is easy to understand why Arenas, who suffered along with the LGBQT+ community, would want to tell his story to the world before he died. He has left us not only with a personal documentation of this oppression, but also with inspiring tales of how he and his cuban community fought back by being true to themselves in the face of all of that.

According to recent New York Times Article, in 2010 Castro apologized for the repression of homosexual cubans and his own responsibilty in that oppression. Today, led by Castro’s niece, Mariela Castro, Cuba has changed cuban laws and Cuba is now considered a world leader in LGBQT+ rights. What a shame that Arenas didn’t live to see and enjoy it.

For more annotations, check out this link.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is important and ¿por qué?

Heroines, Role Models, and Everyday People

I am heartbroken

Mi corazón está sumamente triste

She was such an AMAZING human being

Un ser humano extraordinario y lleno de amor y bondad

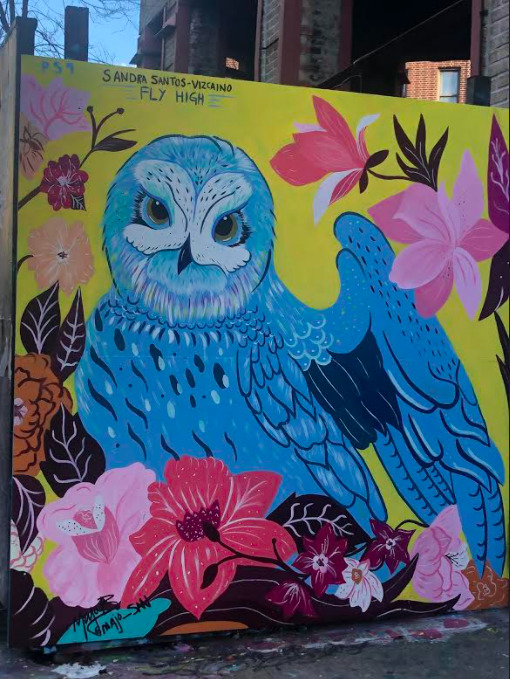

These were some of the Facebook posts in the days after my friend Sandra’s passing on March 31, 2020. According to this ABC news article, she was the first teacher we lost to COVID in New York City. These were early days in our latest collective experience of human frailty brought on by this crazy pandemic. At the time, newspaper articles showed crisp charts with very tall bars for people over 65, but the bar for Sandra’s age group was pretty short. Sandra was my neighbor, my friend, and my peer. At 54 years old, we were the same age. Our kids were the same age, we’d both been dual language teachers for years, and we’d shared our dreams for supporting Sunset Park kids when we retired. My dream was to help kids with all of those little gaps in support as they head off to college. Hers was to start a really great preschool for families that couldn’t afford it. For me, the virus now felt real and personal; I now knew that the virus could take something from me, something important. In addition to the personal impact on me, the effects of Sandra’s death reverberated throughout our Sunset Park community. Sandra was an everyday, regular person in my life. But the way she lived her everyday life, made her special. For many, Sandra was a role model, and even a heroine.

In the days after her death, Facebook was filled with posts about what made Sandra so special (including, She was just the type of everyday superheroine that Dulce Pinzón portrays in her photographs at https://www.dulcepinzon.com/.

The New York Times, The Daily News, Democracy Now, Chalkbeat, NYSUT, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-NtmrK-S8g ). One of the posts listed the many awards she won for her teaching. Other posts told stories of all of the special ways that Sandra helped her students, her friends, her neighbors, and her family. Still others just talked about her warmth and kindness. Recently, I was in Prospect Heights and I ran across this mural commemorating Sandra from her school community. (It turns out it is part of a project, Underhill Walls, started by Jeff Beler collaborating with Love Heals to beautify an abandoned building. Sandra’s mural was recently added to the mural.)

Just to give you an idea, let me go back in time to tell how Sandra and I started to become friends…

Years ago, when my father was ill, we brought him to live with us. Soon after he arrived, my principal called me down to the office. My father had fallen in the bathroom. He hit his head and broke his hip, said the voice on the phone. Under the influence of strong, prescribed medications, my father’s lucidity came and went. The doctors told me I needed a Durable Power of Attorney, if I wanted to be able to make his medical decisions in his less lucid moments. To get that, I needed a notary public. This detail became a stressful task at the time, getting between me and my father’s care. After all, how can you get a notary public into the hospital and one that will keep coming back until he’s lucid?

Somehow Sandra heard about our situation and she reached out to me and volunteered; it turned out she was a notary public! She came to the hospital two or three times until my father was cognizant enough to go over the paperwork and understand what he was signing. Each time, I apologized and thanked her profusely. Each time she threw her head back, smiled a wide warm smile, and said it was no big deal.

At the time, I barely knew her. But, over the years, I learned that this is who Sandra was. She had two young kids, was helping to raise her sisters’ kids, taking care of older parents, and teaching full time in Red Hook, three neighborhoods away. And, every time I saw her, she shouted across the street and we chatted.

At the time of Sandra’s death, so early in this pandemic, this was a huge loss for me, a personal, heartbreaking loss. It still is.

Since then, I have come to wonder if this wasn’t more than just a personal loss, both because Sandra touched so many lives and also because, being Dominican, she was Latin@.

Back then, I was worried about my mother, my aunts and uncles, my friends’ parents, my older friends. I was shocked time and time again, as my friends lost family members at an alarming rate. One of my colleagues at school lost her father and her 24 year old brother within days. Another friend’s husband lost his grandparents and his father was in ICU for what seemed like ages. My student teacher’s grandmother was in the hospital for weeks. One of my professors told us to please be careful over Christmas break, because she had lost 3 family members within a week after they had a small birthday gathering. At some point, I realized that every last one of these people we had lost were Latin@ or Black. Before the press started reporting about the inequities of the ravages of the virus, it was becoming obvious to me.

My white 77 year old mother and 78 year old mother-in law were fine, even though the former kept going out to buy food, shop for non-essential items and the latter lived in a nursing home. My sister-in-law and nephew survived infection unscathed, even though they both had significant risk factors. In fact, my white family members and my many white friends were mostly fine. I’ve heard of only a tiny handful of white people who have lost family members or friends, mostly older and with quite serious underlying conditions.

By April 10, 2020, news articles like this NBC article were starting to pop up. According to the COVID Racial Data Tracker, a collaboration between the COVID Tracking Project and the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research, Latin@s are dying at a rate of 167 per 100,000, while whites are dying at a rate of 121 per 100,000 (Here is the link).

Sandra wasn’t pushed out of the neighborhood by gentrification and, since she owned her home, she wouldn’t likely have been. Still, she’s gone and I can’t help but think that, if she were white, she’d probably still be here. My anger, frustration, and resentment are palpable as I write this. Sunset Park is less without Sandra. How many other regular people, role models, and heros have we lost in the Latin@ community?

NOTE: Other challenges for the Latin@ community have been access to educational resources (like waiting so long for DOE iPads and ongoing challenges with Internet access, unemployment, and food insecurity, and access to vaccines).

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunset Park - Changes

Mexican Artists- Street Art MuralStreet Muralismo When we first moved to Brooklyn, my daughter had just turned five. My husband and I met in New York, but just months later, he followed me to grad school in Chicago, then Costa Rica, Michigan, and finally, back to Brooklyn. I didn’t want to come back. Living in Sunset Park, Brooklyn was our compromise; I agreed to come back if we could live here. There was a good Dual Language school I had scouted out for my daughter and the neighborhood felt less hectic and pressurized than many other parts of the city.

The morning after our move, my daughter Isa woke up with the sun, ready to explore our new neighborhood. As we passed the two story row houses on our block so typical of Brooklyn, I read her the signs on the windows, ‘Se renta cuarto’ ‘Se cuidan niños’ and ‘Se venden…’. ‘Mamí, she said. Listen. But, I had already heard the sound of a rooster crowing. We both smiled and laughed. Over the weeks and months that follows, we got to know our neighbors and hung out for hours on stoops, chatting. We felt like we were home. In the early years, we did leave the neighborhood at times -- most notably to plan lessons in cafes, one of my long time addictions that was nowhere to be found in Sunset Park, but we lived and worked here, away from some of the bustle and urban polish of New York City.

Towards the end of elementary school, my daughter started commenting on the increasing number of ‘white people’ walking to the train as we walked to school together. By the time Isa left high school, property values had shot up from the $200,000s to the 1.x millions for a two family home. In grad school, I had studied gentrification and read vignettes, similar to the ones we read last week in this class, about people being pushed out of their homes by increasing housing costs. But, I’d never experienced it first hand. Those who had purchased their homes in time took a collective sigh of relief or frantically sold them for a huge profit, strutting their profits, disappearing to Puerto Rico to retire comfortably… The school where I taught for many years started losing students who could no longer afford to live in Sunset Park, still one of the least expensive neighborhoods in the city. They were going to places like Pennsylvania and North Carolina. One family I loved came back saying the government benefits were so much less generous there than here, but most didn’t return.

While our imagined community have changed, the physical boundaries of our neighborhood have changed as well. What was once Sunset Park has become Greenwood Heights, as people from Park Slope, our richer neighbor, move further into Sunset Park. The vestiges of the long gone shipping industry once dominated the water front in Industry City.

The new iteration of Industry City, first officially proposed in 2015, has brought in a number of swanky businesses, cafés, and even a hat store.

Bush Terminal Piers Park opened in 2014, reclaiming a pollutant dumping ground.

More recently, Citibike stations have been popping up just blocks from my home in the heart of Sunset Park.

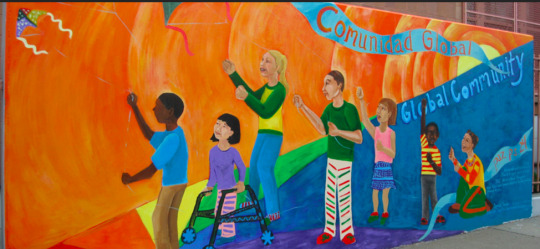

Throughout this same period, Groundswell has been organizing mural projects around the neighborhood. On the one hand, this feels like gentrification. On the other hand, these murals often depict Latinx themes and celebrate a long history of mural art in Mexico (by artists like Frida Khalo and Diego Rivera) that has influenced American art since the early 1900s. For more information, check out Latino Mural Art in NY and Mexican Artists- Street Art MuralStreet Muralismo.

The mural below is one such project. It was designed and painted in 2011 by lead artist Katie Yamasaki, assistant artist Tanya Linn Albrigtsen-Frable, and several P.S. 24 students (many of whom were in my class at the time!). The work was created to represent the diversity and values of the school community. You can learn more about Groundswell and this mural at P.S. 24 - Comunidad Global.

This mural, was also organized by Groundswell, but in 2013. The lead artist was Olivia Fu, with assistant artist Eduardo Vazquez and several P.S. 24 students, including some of mine. Click to find out more information about this P.S. 24 mural.

Even beyond the murals, Sunset Park still feels like a Latinx, working class neighborhood, but it has become a neighborhood of contrasts.

It has been years since I’ve heard a rooster. The people I know personally in Sunset Park have only changed a bit, but my imagined community seems to be changing a lot; it feels like only a matter of time before it impacts who I know here. On the bright side, there are two cafes within a mile of my home where I can get a great latte. If I want, I can even get a decaf with soy or oat milk. I’d give it up though to have my family come back.

15 notes

·

View notes