Text

Review Post

Two (Or Two Hundred, Or Two Thousand) Households, Not All Alike In Dignity

There are more Romeo and Juliet adaptations than just the ones I’ve talked about here. I didn’t even get into the opera, or the animated garden gnomes, or the thousands and thousands of movies that are technically related to Romeo and Juliet in some way. There are more adaptations than you could reasonably expect anybody to count, and by the time you got done counting, you wouldn’t have energy for much else. And yet, not everything can make it into every adaptation. The mediums demand changes, whether because of time conventions or what’s physically possible or what the people adapting the story feel like doing at the time. When cuts get made (and they do get made), they tend to be made to everything but Romeo and Juliet. When you cut it down to just one person on the ice with four minutes, the basics of their interactions with each other are still there. That doesn’t mean those sections are immune to changes, though. Just about anything can be changed, because even though I have lots and lots of opinions, none of my opinions are actual rules.

Romeo, Oh Romeo!

With Romeo, nearly every adaptation cuts into or entirely cuts out his initial infatuation with Rosaline. West Side Story and all of the music and figure skating adaptations have no mention of her at all, while the 1968 film only has Friar Laurence mention her once. The reduction and erasure of Rosaline serves to make Romeo more likeable; the audience doesn’t want a protagonist whose affection seems fickle. Why would we want him and Juliet to be happy if we think he’s going to be over her in a minute? So Rosaline tends to get the axe, with the notable exception of the ballet. There, the production really leans into Rosaline, going so far as having her that appears on stage. The choreography around Romeo dancing with the handkerchief shows pretty clearly that his affection for her is surface-level, and he actually returns the handkerchief in the beginning of Act II of the ballet. This was a clever way of keeping Rosaline in the show while still showing that Romeo is now quite serious about Juliet, and it was one of the reasons he was a particularly likeable Romeo amidst the sea of Romeos.

Romeo is also a bit of a goofball when the adaptation gives him the time to express that part of himself. In the 1968 film, he runs with glee towards Friar Laurence to tell him of his intentions to marry Juliet and he has to be literally pulled away from her once she arrives at the church. That film and the ballet also frequently show him goofing off with his friends, singing and playing pranks and generally being delighted by life. In West Side Story, Tony (our Romeo stand-in), is unshakeably optimistic and hopeful, and he’s clearly loved by his friends. Romeo has several pensive moments in the earlier acts, but it’s still made clear that his core isn’t quite as serious as his occasional moping might make it seem. Even the 1996 film, which has the most arguably unhinged and serious of the Romeos, has him get shoved into a pool and get high on mystery drugs from Mercutio. Romeo is serious, of course, but these lighter moments make it clear that if it wasn’t for the situation around him, he’d probably have had a decently happy life. He wasn’t doomed to misery by some defect of his personality, but the world around him.

In the original text of the play, Romeo winds up killing Paris and a servant at Juliet’s tomb before going to see her. Every single adaptation that I encountered removed this detail. Paris is often at the funeral for Juliet when it’s shown, but he’s never at the tomb when Romeo arrives and is never killed by Romeo. Much like the removal of Rosaline, this is done to make him more likeable to a modern audience and to stay more consistent with his dislike of the feud stuff in general. Him killing Paris could be seen as simply a jealousy thing, even if it wasn’t intended like that at all, and so most people choosing to adapt Romeo and Juliet fix this possible perception issue by removing Paris from the situation altogether. It might also be distracting to just have Paris’s corpse there while Romeo and Juliet are having their final moments. The 1968 film and the ballet don’t have an aversion to corpses, but the dead that appear in the Capulet monument in those scenes aren’t newly dead. Tybalt’s been dead for several days by that point, and they’re often covered up by some sort of sheet. Paris’s body would be out in the open, which might draw an audience’s attention away from the main action.

However, removing Paris and the death of Paris’s servant undercuts the amount of despair Romeo is in leading up to his death. He’s obviously distraught, but often not distraught enough to do harm to someone else. 1996’s film solves this by having Romeo briefly take a man hostage before going to see Juliet for the final time, but most don’t do anything about that. At the point that he reaches the tomb, he’s usually more depressed than anything else. All of that outpouring of despair only comes out when he sees Juliet’s “body,” not in the lead up to it. I understand why people might not be down with Paris getting murdered, but I think that we should have more adaptations that bring it back. We can leave his body just outside of the tomb, maybe. There are solutions to this problem.

It’s the Sun! Or Juliet. Romeo Doesn’t Know The Difference.

One thing that stands out in nearly every adaptation is Juliet’s profound sense of isolation. The audience sees Romeo with lots of friends his own age, but Juliet has no companions. Prior to Romeo, her world consists of four people: Her parents, her nurse, and Friar Laurence. Her relationship with her parents is strained in most adaptations even before the introduction of Romeo: she makes faces behind her mother’s back in the 1996 film, is stiff and awkward in the 1968 one, can’t clearly follow Lady Capulet’s directions in the ballet, and even some music mentions it. It’s not known how often she sees Friar Laurence at the start of the play, but it hardly seems like they’re close at all. Her only true companion is the Nurse, who acts much more as a mother than a friend, and even she is bound to listen to the Capulet parents. This isolation even comes through in figure skating adaptations; there’s a reason singles skaters tend to portray Juliet more than Romeo, and part of it is because on an emotional level, she’s on her own out there. No one can truly look out for her best interest. Juliet’s universe is small, and she has very little say over it until she meets Romeo and begins to make decisions for herself.

There’s one startling exception to what I’ve mentioned above: West Side Story. That musical gives Maria (who acts as our Juliet) her own circle of friends at the bridal shop. She also has a close relationship with her brother’s girlfriend that’s independent of her brother, and her parents are never openly cruel to her. The conflict in West Side isn’t caused by individual families, so that allows her to have more personal support systems. This is also at least part of the reason that Maria doesn’t kill herself when she finds out that Tony is dead. She knows that she can go home, that she can be supported by some of the people around her. None of the other Juliets have that option. Once they’ve picked to follow their heart, they can never go back home. If Juliet walked out of that tomb, there’s a high chance that she would have been sent back into it.

The Capulets take the abstract threat of the family feud and parental disapproval and make it very real. Lord Capulet’s refusal to listen to Juliet, his credible threats of throwing her onto the street, and his often physically abusive actions in response to her not wanting to marry Paris make it clear that he’s not going to take Juliet’s marriage to Romeo very well. He’d follow through on all of his threats, if not worse. Lady Capulet offers Juliet no assistance, and makes it clear that if Juliet wants to defy her father, she’ll be doing it on her own. The Nurse is also quick to tell Juliet that she should go along with her parents in every adaptation, but she’s at least nice about it. All of this leaves Juliet with literally one ally left in the world, and so it’s not surprising that when she gets to Friar Laurence, she’s desperate enough to fake her death. When the audience sees the way that they mistreat Juliet even without knowing, it’s not hard to imagine that it would get much, much worse if they found out that she crossed the lines of the feud to marry Romeo. This urgency to keep the situation a secret is a huge part of why Juliet fakes her death in most adaptations (in West Side Story, Anita tells the Sharks that Maria is dead when she actually had no intentions of fake dying at all), and her faking her death is what winds up with both her and Romeo dead for real. And yet, with the threat of her own family hanging over her head, Juliet’s actions seem almost reasonable. At that point, there’s no good way out for her because she has no genuine outside support. And while I love seeing Maria have agency and take control of the situation around her in productive ways, the distance that most Juliets are forced to keep from the rest of the world hits hard. It makes her situation all the more devastating, or maybe that’s just my quarantine brain talking. Who knows.

Violent Delights and Their Violent (and Nonviolent) Ends

Even though the ending of Romeo and Juliet is one of the most well-known parts of the play, several adaptations have made changes to it. Both films followed the plot points fairly closely: Romeo arrives at Juliet’s tomb (after killing Paris, which all adaptations removed), kills himself, Juliet wakes up, discovers that he’s dead, kills herself, and then the families end the feud. Interestingly enough, the 1996 film lets Romeo and Juliet make eye contact before they realize all is doomed. Juliet wakes up just as Romeo drinks the poison, and they’re allowed a final kiss before their deaths. The change there was small, but it added an extra layer to the tragedy. At that moment, they both knew that it didn’t have to end the way that it did, but it was too late to do anything about it.

In West Side Story, it’s mostly Maria who brings an end to the feud. When Tony dies, she’s the one who demands that everyone drop their weapons. Even though she briefly threatens to shoot several people and then herself, ultimately, she drops the gun. Slowly, the feud ends, one gang member at a time getting together to form Tony’s funeral procession. It only took the death of one of the lovers for everyone to realize that things had gone too far and needed to be stopped, and Maria’s insistence that it all stop cemented that the feud needed to end. This is a fairly radical departure from the original, but it still keeps the spirit of it. The deaths that do happen are painful in the fact that they could have easily been avoided. and even one of the protagonists wasn’t immune to the feud getting to them.

The ballet, most music that includes Romeo and Juliet’s death, and nearly all figure skating adaptations end as soon as Juliet dies. The removal of the families formally ending the feud forces the audience to more deeply consider the deaths of the protagonists. This ending centers the story on Romeo and Juliet themselves instead of the feud around them, and takes away any chance of a feeling of “Well, at least they’re doing the right thing now.” Ending it on the note of Juliet’s death leaves the official status of the feud unresolved, but adaptations that go for this route are much less focused on the feud as its own independent force and are more focused on how it affects the main characters. Their view is more personal and less sociological, and so it makes sense for those adaptations to end it on their deaths.

A not-insignificant portion of Romeo and Juliet adaptations give the lovers a happy ending. I personally find this infuriating. If the feud could have been stopped by love and affection, it probably would have been stopped ages ago. Romeo’s plea to Tybalt in Act III that most adaptations include would’ve ended it. The point of Romeo and Juliet dying is that love wasn’t enough to stop the overwhelming forces of hate and misery around them. It’s only once the major families have both lost their own children that they realize that the feud is actually pointless and harmful. If the deaths of servants and loosely-associated friends and cousins was enough, it would have ended with Mercutio and Tybalt, or it would have ended before the story even began. If people want to talk about a story where love overcomes all odds, they should simply tell a different story. It’s tempting to want to give Romeo and Juliet a happy ending; they’re both characters that are easy to sympathize with and root for. But giving them a happy ending does the core of the story a great disservice, unless someone felt like ending the story with them meeting up in heaven or something. Even then, that would be kind of cheesy. It’s honestly better for everyone to stick to the tragic endings. An ending doesn’t have to feel good in order for it to be good.

Parting (Which Is Such A Sweet Sorrow!)

Across hundreds of years and all the continents on earth (except for Antarctica, unless the penguins are up to something I don’t know about), people have been adapting Romeo and Juliet. Even Shakespeare’s play, despite serving as the main base for everything I’ve talked about so far, could technically qualify an adaptation. There was The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet before it, which was one of many sources for the play, and that in itself was based on a folktale that wasn’t written down yet. It goes back and back and back, because even if it changes forms, humans will always have love and larger forces that stop it from going well. People are predisposed to talk about it in every format available to them, because talking and making stories is just what people do. Romeo and Juliet is a deeply universal tale, and even if there are changes in the details, the center still holds.

Also, I’d really like to make all continents a definite statement. The penguins deserve to be included in all of this, too. We shouldn’t exclude the penguins.

0 notes

Text

Romeo and Juliet in Figure Skating

Romeo and Juliet is something of a warhorse in figure skating. In just about every competition and at nearly every level, there’s a good chance that at least one skater will be using it as one of their programs. While it’s more common in singles skating and at the junior level, it’s entirely inescapable. However, that doesn’t mean adapting Romeo and Juliet to figure skating is easy. Much like ballet, they only have the music and their bodies to work with. However, they also have a time limit (free programs can’t be more than four minutes; older rules occasionally allowed men’s programs to be four and a half minutes, but that’s not much better) and instead of a whole cast of characters, there are only one or two skaters on the ice. This only allows them to focus on the main plot, but it also allows them to put all of their energy into telling just one specific part of the story. It can be a hindrance, but also an opportunity. Most programs follow the pattern of a serious music cut, a soft and romantic cut, and another serious cut that’s meant to represent Romeo and Juliet’s death. Still, within this pattern, there’s lots of room for innovation and experimentation.

Ekaterina Gordeeva and Sergei Grinkov (Watch here)

Widely considered to be one of the best pairs teams in the history of the sport (there’s a lot of argument about it because there are so many good pairs teams), Ekaterina Gordeeva and Sergei Grinkov skated to Romeo and Juliet in 1990, earning them a gold medal at the World Championships. They picked Tchaviosky’s suite, but because you apparently can’t do a twenty minute free skate, they cut the music and moved some things around for length requirements. They followed the typical serious-soft-serious pattern of mood for the music cut, and while it wasn’t especially unique, it worked for them. Like a lot of skaters who skate to music from Romeo and Juliet, they went very Italian Renaissance with their costumes, just to make sure we all get what they’re skating to. On a personal note, I really appreciate the level of puff on Sergei’s sleeves. A lot of men’s costumes are very plain, but he went for the drama. Good for him.

Their skating was incredible. Ekaterina made two mistakes on jump landings, but their throw jumps were huge, their lifts got insane distance and speed across the ice, and their skating skills are to die for. Seriously, I can even see how deep their edges are on that video, and that’s footage that was very clearly shot in 1990. Who needs side-by-side jumps when you can do that? And they were far enough ahead of the rest of the field that they could afford those mistakes. Ekaterina and Sergei had great sync with each other here; it felt like watching two parts of the same machine. I never felt like they were going to fall. Even when they did mess up, I wasn’t nervous because they skated and told the story with so much confidence. 8/10

Sasha Cohen (Watch here)

So I’m not usually a person that likes things that make them cringe, but I love Sasha Cohen’s Romeo and Juliet. Was it a mess? Yes, but stick with me here. This program did, in fact, cost her an Olympic gold medal. She fell, twice, in the free skate at the Olympics. And not even in men’s, where they spend half the time on the ground anyways! This was a group of ladies who knew how to land jumps. But the thing about Sasha Cohen’s falls in this program was that she got up and continued the program with such grace that I found myself going with it. That’s the magic of Sasha Cohen. And the falls in this program made it that much more tragic, which works really well when you’re skating to Romeo and Juliet. You felt the despair there. Everyone felt the despair. We all suffered together here.

That aside, Sasha went for the Nino Rota Love Theme (you can check out my thoughts on that piece here), and it really worked for her. The softness of the piece allowed her to be very gentle. The emotion expressed here was all in subtle facial expressions and delicate arm movements and it snuck up on me. I didn’t notice how attached I got to her performance until it ended. Her spiral sequence was iconic, her spins were as lovely as always, and no one has ever come close to her perfect posture. And hey, she did well enough in the short program that she did wind up with a medal! Just not the one she had wanted. 7/10, because her falls here made me wince so hard that it hurt my face.

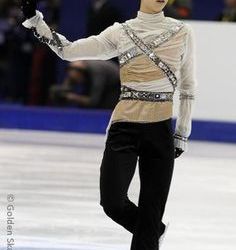

Yuzuru Hanyu (Watch here)

So the interesting thing about Yuzuru Hanyu is that he actually has skated to Romeo and Juliet twice; first at 17 when it won him his first World Championship medal, and then again at 19 when it won him his first Olympic gold. I’m analyzing the first one on account of liking it more, but honestly, they’re both great. Plus, the first Romeo and Juliet (affectionately called R&J 1.0 by fans) is what launched his career in seniors and allowed for him to eventually win that first, and then a second, Olympic gold. It’s worth attention.

The costume here wasn’t exactly Italian Renaissance men’s fashion inspired, but it clearly gave off a dramatic, historical vibe, so I approve. And his emotional investment in the program is just insane. For the louder, dramatic portions, he’s emoting all the way to the back of the stadium, but for the softer, lovey-dovey section in the middle, his movements are soft and gentle, with all the subtlety and grace of Sasha Cohen. He goes everywhere on the emotional spectrum here, and is able to do it effortlessly. Yuzuru is out there forcing the audience to feel invested in the story he’s telling, making us understand the high stakes and get invested in the romance because he’s clearly so invested in it. On a more technical note, his jumps are out of this world and the knee bend on his landings should be in physics textbooks because honestly, how does he do it? It’s a mystery that we’ll need science to solve.

He does have a minor fall on some steps, but it’s less agonizing than Sasha Cohen’s falls because the competition is slightly lower stakes, and Yuzuru went into this World Championship with nothing to lose. It was his first ever time at senior worlds, and he wasn’t favored to podium at all. Sasha, meanwhile, was the favorite for the Olympic gold. Big difference in falls there. Also, the scream right as the music changes into the step sequence? The stabbing choreography? Yeah. He went for all of that. He didn’t hold anything back. 10/10, Yuzuru Hanyu told everything he could of that story with everything that he had, and it was excellent.

Anastasia Gubanova (Watch here)

This program is technically the most stereotypical Romeo and Juliet program of all of them. It’s in the demographic that uses Romeo and Juliet the most (junior ladies), done with one of the music pieces most often used in Romeo and Juliet programs (Nino Rota’s Love Theme), and is typical down to the costume (Renaissance Italy with a cross somewhere on it). This should, in theory, bore us all to tears. But just because Anastasia Gubanova isn’t breaking any new ground here doesn’t mean that this isn’t a fantastic program. This program shows why so many of these choices get made, because when they’re done well, they’re incredibly moving.

Anastasia’s program has a melancholy feel form start to end, although it gets more serious and doomed as the ending draws nearer. Her jumps are light and airy, and she skates with a confidence and grace that makes it hard to believe that she’s only fourteen years old. She has a total commitment to the choreography, although that sometimes makes some of her arm movements just a little bit too wavy and distracting. She resolutely stays in character as Juliet except for when she lands her last jump and it becomes clear she’s landed all of them perfectly, but the breaking of character for a smile is more endearing than distracting. Plus, she managed to get right back into it for the last spin. All in all, an impressive program that makes it clear why some typical Romeo and Juliet program features became so widely used. 8/10

Junhwan Cha (Watch here)

Unlike just about every Romeo and Juliet program I’ve ever seen, Junhwan Cha did a program based on the 1996 movie instead of just using some music from it. As in, he used the funky pieces that most skaters tend to skip over and fully leaned into the weirdness. He even went for ending the program on a gunshot instead of the typical stabbing choreo! It sort of followed the basic serious-soft-serious structure of Romeo and Juliet programs, but with a bit of disco in between each one. And do you know what? He basically pulled it off, and was really committed to some of those choreography choices.

There were a few things about this program that I wasn’t a fan of. I didn’t love the voiceovers, especially the one that was just reading the prologue of the play. I thought they were a little corny, and it only worked on the last one. I’m sorry, but the absolute drama of Leonardo DiCaprio screaming “Juliet!” while Junhwan lands a triple loop and does that thing with his arms? That absolutely worked. The other voiceovers could have been cut, though. He also didn’t have the skating skills and emotional expression of the other skaters I’ve talked about so far. Junhwan was by no means bad (he won bronze at the Grand Prix Final for a reason), but it wasn’t quite at Yuzuru, Sasha, or Gordeeva and Grinkov’s level. Still, he did something unique and surprising while keeping the story in tact, and I appreciate that. 7/10

Madison Hubbell and Zachary Donohue (Watch here)

There are things that I do like about Madison Hubbell and Zachary Donohue’s Romeo and Juliet. There were a few interesting chorographic movements! Their lifts were solid! They had solid skating skills (as they should; ice dance is all about basic skating skills) and were super fast across the ice! It’s just that there was far much more to dislike about this program, which is rough for me personally because it won them a bronze medal at the World Championships that I would have much rather given to the team that placed fourth.

The costumes here were just objectively awful. It’s okay for Romeo and Juliet programs to not have Renaissance-inspired costumes, but what’s not okay is that strange color that’s between beige and dishwater gray for Madison’s dress. Zachary’s costume did just about nothing to mitigate the damage. The opening arm movements were stiff and awkward, the voiceovers were once again not great, the third music section was tantamount to torture (the dramatic piece was fine, but it had bits of “Kissing You” poorly edited in), their chemistry on the ice was mediocre at best, and they committed the unforgivable sin of giving Romeo and Juliet a happy ending. It’s just...not what the story is for. The whole point is that the violence and misery doesn’t resolve until at least one of the lovers dies. But they went for a happy ending, in which case, they should have just done a totally different program. 2/10

0 notes

Text

Romeo and Juliet in Music

Romeo and Juliet has been showing up in music for well over two centuries now, but that doesn’t mean the medium is a forgiving place to tell the story. Much like the ballet, the older or more traditional songs have to rely solely on their instruments to get across a complex, layered plot to an audience that’s only listening. Unlike the ballet, though, those songs don’t have a dancer’s body and movements to help them out; they’re completely on their own. The arrival of more lyrics in songs has made getting the story across a little easier, but how do you condense a two-hour play into something that can be played in under five minutes? You could summarize it, sure, but that wouldn’t exactly get across any emotion. But even with all of that, people are still putting this story into songs. I’ve picked out a few of the most popular examples below.

Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet (Listen here)

First written in 1870 and not completed until ten years later, Pytor Tchaikovksy’s Romeo and Juliet is a 20-minute long overture. It’s split into three parts: the first part is meant to represent Friar Laurence, the second part is for the warring Capulets and Montagues, and the final part is the “love theme,” which represents Romeo and Juliet’s relationship. The music itself is pretty phenomenal, which is what you get when you’re dealing with Tchaikovsky.. There are racing, anxiety-inducing violins and oboes that sound like pure doom, but there are also sweet little flute parts that warm your heart. Also, as someone who was in the percussion section of her school’s band for years, I appreciate a good timpani part when I hear it, and the timpani here was noticeably fantastic.

This piece also has one of the most famous melodies of all time, and you’d think the section wouldn’t hit hard because you’ve already heard it a thousand times, but luckily, that wasn’t the case. It felt genuinely emotional. Even though the music was moving and clearly telling a story, it was pretty hard to figure out what each section clearly represented unless you did some reading beforehand. But even without knowing which part is for Friar Laurence, the melancholy and love contrasted with war and doom was still very clearly Romeo and Juliet. Still, I’d have liked to been able to more clearly know what was going on. 7/10

Love Theme by Nino Rota (Listen here)

Nino Rota wrote this three-minute piece for the 1968 Romeo and Juliet film (reviewed here), which also serves as the backbone for “What Is A Youth?”, a song that’s sung in the context of the film itself. It’s not nearly as long or complicated as Tchaikovsky’s attempt at getting the story of Romeo and Juliet across without words, as it’s mostly carried entirely by one violin. The melody is melancholy and nostalgic and overall, it’s effective. It aims for the softer, sad parts of the play and it hits them. It doesn’t tell the whole tale, but also, it isn’t trying to get across every nuance. It’s just going for the general mood, and it gets that. 8/10

Somewhere by The Supremes (Listen here)

Originally written by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim for West Side Story (reviewed here), The Supremes decided to cover it in 1965 and they did a fantastic job. The moody trumpet and general jazzy feel makes it stand out. Despite jazz generally being upbeat, there’s a definitively tragic tone here with a distant hope, the idea that “somewhere, there’s a place for us,” but that somewhere isn’t here. The vocal parts are split perfectly and compliment each other well, and the final note is extremely strong. Another 8/10

Romeo and Juliet by Dire Straits (Listen here)

I’m going to be honest: I hate this song. I hate it so, so much. This isn’t even coming out of a place of hatred for 80s music. I love 80s music! I just hate this song. The lead singer’s voice only ever hits one aggravating note that barely counts as a note, the guitar part is repetitive without being catchy, and the rest of the instruments are non-offensive, but they don’t make up for the hot mess that is this song. However, the worst part has to be that despite being one of the most popular uses of Romeo and Juliet in music, it has just about nothing to do with Romeo and Juliet. It feels like they just put the names in there at random. In this song, Romeo and Juliet were together, but Juliet got bored of Romeo and left, and now Romeo is depressed. Honestly, if they wanted to make an allusion to Shakespeare, Rosaline and Romeo would fit much better, but the fit isn’t very close and those names don’t sell records. There’s no reference to the family strife that borders on a gang war, none of the emotions or themes one might associate with the story, nothing. They aren’t even dead at the end of the song! This is not Romeo and Juliet. This isn’t even an allusion to Romeo and Juliet. This is a crime against me personally. Its continued existence plagues my nightmares and my heart will never know peace or joy. Why did God allow this to happen? 1/10

Exit Music (For A Film) by Radiohead (Listen here)

Much like the name implies, this song is the end credits for a film! Specifically, it’s the end credits song for the 1996 movie version of Romeo and Juliet (reviewed here). This song was written based on scenes sent to the band by Baz Luhrman, which included the scene where Romeo and Juliet meet and the last 30 minutes of the film. The instrumental backing is gloomy, and the lyrics hint at family strife and two lovers escaping before taking a turn for the worse, for what is clearly their deaths. There’s an actual choir in the background, and by the end, the overwhelming sense of defeat and emptiness makes me want to lay down on the floor for several hours. 9/10

Love Story by Taylor Swift (Listen here)

This song is so incredibly catchy. Listening to it just once will have it stuck in your head for the rest of the week, if not the month. And at first, that’s great! But it does get old after several hours of having it on loop in your brain. There are lots of things in this that are clearly very Romeo and Juliet in this song, including family disapproval of the romance, a balcony, and mentions of a ball. Unlike some songs, the names weren’t just thrown in there just to be there. However, it’s very upbeat, which can work if you’re talking about the first two acts. Unfortunately, it stays upbeat throughout the entire song, and Romeo and Juliet are given a happy ending with family approval and no murder. I get why people like happy endings, but a happy ending to Romeo and Juliet undermines everything that the play is about. Just write something else if you want it to end without bloodshed; leave Romeo and Juliet alone. 3/10

0 notes

Text

2016′s (or, arguably, 1938′s) Romeo and Juliet

Basics

Title: Romeo and Juliet

First performed: 1938

Performance reviewed: 2016 by the Royal Danish Ballet (watch full performance here)

Composer: Sergei Prokofiev

Choreographer: John Neumeier

Main ballerinas: Ida Praetorius, Andreas Kaas, Sebastian Haynes. Susanne Grinder

Script and Plot

This adaptation of Romeo and Juliet is notably scriptless, but it’s not because some artistic statement about silence or anything: that’s literally just how ballets work. There’s no speaking. For two and a half hours, nobody says a word, and that’s just how it is. This has some advantages (you can’t say Shakespeare’s lines stiffly if you’re not saying anything), but it can also make it tricky to understand what exactly is happening on stage. The good news about that is that most ballets come with small summaries of what happens in each act, but they’re sometimes vague enough that it can still be tricky for someone who isn’t used to watching them.

This production makes several changes to the original plot. Romeo and Mercutio are there at the initial fight scene, and engage in a bit of swordplay with Tybalt; the Capulet and Montague servants who start the fight in most adaptations don’t show up at all. Rosaline, a character who’s notably unmentioned by several adaptations and doesn’t physically appear in Shakespeare’s play, actually appears on stage in this one. There’s also the addition of a wedding procession for an unknown couple in the beginning of Act Two (would be the beginning of Act Three by the Shakespeare script, but ballets are three acts instead of five), and also a dream sequence that occurs after Juliet has taken the medicine that will put her in her death-like sleep. The ballet ends right on Juliet’s death, eliminating the final scene where the families come together, which makes the tragedy feel final and unfixable. Finally, Romeo doesn’t kill Paris or his servant, a change that seems to be fairly standard among adaptations.

Characters

Juliet in this adaptation is awkward. You’d think that would be an insult, but it isn’t. The awkwardness here is sweet and playful, and it really gives a sense of her personality. It’s not the fault of Ida (who portrays Juliet), but actually part of her characterization. You can see the feelings coming off of her in waves, the need for love and affection with almost no restraint. There are moments where Juliet’s obviously nervous and unsure of herself, most notably at the Capulet’s ball, and it makes it impossible not to sympathize with her. Her and Romeo’s love is playful and sugary-sweet when they’re together, and it makes the audience continue to root for them even when the ending is inevitable. Romeo is a bit more trigger-happy in this adaptation than others, more involved in the feud, but he also is still a bit of a goofball. When he’s infatuated with Rosaline, he dances with her handkerchief, and he quite literally sprints towards Juliet whenever he sees her. His emotions are as strong and dramatic as Juliet’s, although he acts on them more certainly than she does.

Lady Capulet’s performance (portrayed here by Susanne Grinder) was an absolute knock-out. Her presence was enormous and elegant, and she was absolutely terrifying. Seeing her constantly correct Juliet and serve as the connection between Juliet and Paris makes it clear that she’s a threat to what the audience is rooting for, and her performance never falters. Mercutio and Benvolio were both fun to watch here, as they spent quite a lot of time together joking with Romeo and causing fun, light disruptions. Seeing Mercutio so happy and light and flirtatious (he has something of a girlfriend in this adaptation, which is definitely a unique choice) makes his death hit even harder. I also loved Friar Laurence in this adaptation. He’s fairly young here, not much older than Romeo and Juliet, and he becomes less of an authority figure and more of a stumbling teenager in his own right, whose attempts to do the right thing are mistaken, but clearly well-intentioned. The only major complaint I have has to do with Lord Capulet and Tybalt; it was extremely difficult to tell them apart. There were some points where it was obvious who was who (when they were interacting with only each other, when Tybalt was starting fights, and after Tybalt’s death), but there were other times where it was much harder to tell. They had similar faces, were around the same height, had the same hair color and facial hair, and a lot of the same facial features. It was hard enough to tell who was who on video, but I imagine it would have been borderline impossible from the back of a theater.

Style and Medium

Because of the lack of script, a lot of the emotion in the ballet is riding on the music, and the score is excellent. It’s conflicting and racing during the fight scenes and scenes that foreshadow the tragedy to come, but it’s also light and airy and downright charming where things are easy. And by the ending, when things have gone irredeemably bad, the instrumentation is downright apocalyptic. The melodies are catchy, and when the mood changes, it’s never awkward or stilted. I’ve been humming Dance of the Knights since I first watched it, and will probably be humming it for the next several years.

I can’t say too much about the dancing, on account of not being any sort of expert in ballet. I thought it looked great, though. I was especially impressed by a bit in the first act when Lady Capulet is showing Juliet a dance, and Juliet messes it up. But the mess up isn’t a fault of the ballerina, but something that’s clearly choreographed. It’s hard to do anything wrong on purpose, especially when you dedicate years and years to getting it right, but Ida Praetorius manages to do it. The costuming was very much inspired by Renaissance Italy, and I appreciated that for the sake of the audience, a lot of the characters showed up in the same colors throughout the ballet. Doing that would definitely make it easier for those in the back of the theater to tell who was who. However, Tybalt and Lord Capulet, whose physical similarities I already complained about, were also costumed really similarly. That made it even more confusing, and if they had just consistently shown up in different colors, I doubt I would have gotten them mixed up at all.

Final Thoughts

The stunning music, well-done acting and dancing, and care that obviously went into this adaptation makes it worth a watch for those who don’t mind ballets. But if you’re a person who can’t do two hours without a single word or aren’t a fan of scenes that have no basis in the original story, this isn’t going to be for you.

Rating: 7/10, closer to an 8 than a 6

1 note

·

View note

Text

1996′s Romeo + Juliet

Basics

Title: William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet

First Released: 1996

Director: Baz Luhrmann

Main actors: Leonardo DiCaprio, Claire Danes, Harold Perrineau, John Leguizamo

Plot and Script

Much like the 1968 film version (review here), 1996’s Romeo + Juliet doesn’t change much of the script. Some monologues are cut for time, but the original script is largely preserved. What makes this notable is that the movie is very much set in the 1990s. Like, characters have limousines and pink hair levels of “this movie is set in the 1990s.” They don’t even change out the word “sword,” for gun, instead opting to make guns with the brand name Sword. Posthaste is, instead of a word, Post Haste, a postal company that Friar Laurence relies upon to deliver news to Romeo. These changes are kind of ridiculous, but also delightful.

Because the script is so much in tact, the plot doesn’t change too much, either. Paris and Rosaline show up (or in Rosaline’s case, are mentioned) less than in the original play, but more than in the 1968 film. However, that doesn’t mean there are no changes. Romeo’s entrance into Verona after being banished involves a whole helicopter chase and him taking a man hostage. Also, like in many adaptations, Paris and his servant aren’t murdered by Romeo, making the death roll four instead of six. The change that stood out the most to me, though, was that Juliet woke up from her sleep just in time to see Romeo poison himself. They were able to look at each other before his death, and even got to kiss before he passed. I actually really loved this change; at that point, they both knew that their deaths could have been avoided, that none of this had to happen, but it was too late to change anything. It really cements the tragedy of the whole situation.

Characters

Romeo and Juliet are a bit more pensive in this adaptation than others. Romeo spends a not-insignificant amount of time writing poetry, and Juliet’s isolation is fairly pronounced. This change might make them less lighthearted than other adaptations (not that they don’t have their lighthearted moments; they spend a good deal of the balcony scene goofing off in a pool), but it also gives the audience a deep sense that they understand each other. When they first meet at the party, looking at each other through a fish tank, we’ve just seen Romeo head off to the restroom to get a break from all the noise and color, and the audience also just recently saw Juliet avoid all of her mother’s glitz and glamour. We already know that they have similarities, a deep sense of isolation, and it makes the “love at first sight” feel much more authentic. They’re also both the same level of dramatic and unstable. Romeo has his helicopter chase and hostage moments, and Juliet is absolutely not afraid to point a gun at a priest in her distress. While these traits don’t come out around each other and Juliet’s still notably more stable than Romeo, it’s nice that they’re both allowed to go all out.

Tybalt is a complete wildcard in this adaptation. The script is ambiguous about how much harm is done to the city in the opening scene of the play, but here, he engages in a shootout and then blows up a whole gas station with no regard for anyone who could possibly get in his way. He also is wearing the coolest pair of boots I’ve ever seen, but that’s besides the point. The Capulet parents are outright physically and emotionally abusive in this adaptation, with Lord Capulet (named Fulgencio Capulet here) hitting his wife and shoving his daughter, and Lady Capulet (named Gloria Capulet here) clearly not caring about her daughter’s wellbeing. The rest of the cast is well-done and while there are no performances that are objectively bad, Lord and Lady Montague fade away without much notice.

Style and Medium

The style of this movie is kind of wild, and even if I don’t understand every choice, I have to respect the commitment that clearly went into it. Baz Luhrmann didn’t compromise on a thing, and honestly, good for him. The movie leaned into the religious aesthetic, putting images of Mary and Jesus everywhere from Juliet’s room (maybe a bit too much in Juliet’s room) to Tybalt’s gun, but some religious aspects got a modern glow-up. I never thought I’d see so many neon crosses in my life, and while it was distracting at first, it wound up creating a beautiful effect at the end of the movie when Romeo is walking into the church to see Juliet for one last time. Some choices seemed a bit random, though. The abundance of Hawaiian shirts that no one kept buttoned? The random children’s choir that was at Romeo and Juliet’s supposedly secret wedding? The literal helicopter chase that somehow doesn’t result in Romeo’s death? The purpose of these choices beyond the mere aesthetic is unclear. The aesthetic mostly worked and was insanely fun for me, but I can see points where it might be overwhelming for a lot of viewers. The only place where a stylistic choice objectively, unquestionably flopped was the freeze-frame introductions for each character. It was dated and corny and felt like something from a Lifetime movie.

The movie’s soundtrack was also really interesting. There were several songs that were on the softer, sweeter side and orchestral pieces, but there were also a lot of 90s pop songs. It was a mix that shouldn’t have worked, but it did. The music was well-placed, and even if the list looks jarring, it was mixed in such a way that it wasn’t actually too off-putting. It never overwhelmed the scene, which is hard to pull off when you’re putting music from the Butthole Surfers right next to Wagner. Also, I have to applaud the use of Radiohead for the end credits. This is partially because the song is really good, and also partially because I really like Radiohead.

Final Thoughts

With nearly every actor giving it their all, some truly beautiful shots, and one of the best scripts of all time this movie is something to behold. It’s also deeply off-putting if you’re not prepared for 90s-era characters spouting Shakespeare and a bit of style overload. It’s fun and emotional, but also a bit of a rollercoaster.

Rating: 11/10 for me personally, but 8/10 for an actual, semi-objective score.

1 note

·

View note

Text

1961′s West Side Story

Basics

Title: West Side Story

First Premiered on Stage: 1957

Movie Released: 1961

Directors: Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins

Main actors: Natalie Wood, Richard Beymer, Rita Moreno, Russ Tamblyn

Plot and Script

Although the style of this movie is very different from the original Romeo and Juliet, much of the base plot elements stay the same. Some notable changes include the amount of deaths (three instead of six), the removal of Maria (this version’s Juliet) faking her death and replacing it with her friend lying about her being dead, swapping out powerful political families for teenage gangs with racial divides, the more malicious role of law, and the lack of a formal wedding. Most of these changes serve to fit the setting, though; like, it’d be much harder to fake your death well enough to get a funeral in 1950s New York than it would be in 1400s Verona. And two teenagers getting married in that time period isn’t impossible, but it’s also way less common than it was back before electricity was a thing.

The script is obviously pretty different. Frankly, it’d be a little weird if it wasn’t changed from Shakespeare. It’s littered with 50s slang, some of which is a little bit embarrassing to hear in 2020, but it gives it an authentic feel. The teenage characters all sound realistically teenage, even down to the somewhat silly nicknames they have for each other and their gangs. The lyrics to the songs are also quite memorable, and occasionally hit great emotional notes.

Characters

This adaptation changes not only the names of some of the characters, but also their roles. Tony and Maria and straightforwardly Romeo and Juliet, but Bernardo (Maria’s brother and leader of the Sharks) acts as both Lord Capulet for his authority over his sister, and as Tybalt, given that he almost starts a fight at the dance with Tony and dies in the duel. Riff, Tony’s friend and leader of the Jets, is both Lord Montague and Mercutio. Anita is pretty clearly the Nurse, but her age is changed so that she acts as more of a friend to Maria instead of a mother, and the Prince of Verona is split into two characters, Lieutenant Schrank and Officer Krupke.

Tony and Maria’s characters both have the spirit of Romeo and Juliet, but with some significant changes. Tony’s more upbeat than Romeo, with his predictions before the dance being quite cheerful and his confidence in the situation turning out alright is 100% unshakeable. He never has a moment of doubt that things will be okay for him and Maria, but he keeps that same hopelessly romantic air about him. Maria, for her own part, is more assertive and active than Juliet. She opposes the idea of marrying Chino (her brother’s friend and second-in-command) from the get-go, is the one to insist on making plans to meet Tony again, has friends and a social life of her own, and instead of killing herself, threatens to kill others. Although Juliet does gain some agency in the play, hers comes much later than Maria’s, and presents itself more quietly. Tony and Maria’s romantic tension here is alright, but it wasn’t anything too notable.

Minor characters received some more characterization here as well, particularly two members of the Jets, Anybodys and Baby John. They arguably fulfill the roles of Balthasar and Benvolio, and are given clear, distinctive personalities. Balthasar almost disappears in the original, but Anybodys is a spunky, stubborn girl who is determined to make her way into the Jets and helps out Tony several times before his death. And Benvolio’s kindness and caution is taken up several notches with Baby John, and he’s also one of the most openly emotional of the Jets. He even openly admits to being afraid, something that none of the other Jets do.

The most interesting change, in my opinion, are the changes present in the roles of Lieutenant Schrank and Officer Krupke. In Romeo and Juliet, the Prince of Verona is a more objective force, but the officers here are openly aggressive. They threaten the Sharks and the Jets with violence multiple times, and threaten to arrest them at moments when they aren’t even committing crimes. They also both use racial slurs against the Puerto Rican gang members, showing that they’re perhaps picking a side in the conflict. They even explicitly imply that they’re “on the side” of the all-white Jets, but when the Jets don’t comply, they quickly turn to insulting them for being poor and the children of immigrants themselves. This says quite a lot about the society that the characters inhabit, and serves to explain some of the violence and distrust of authority.

Style and Medium

As opposed to Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story really leans into critiquing wider societal issues that are specific to the setting. The Sharks sing a song explicitly criticizing the United States for its poor treatment of immigrants, and the Jets have a song mocking the various social systems that deal with troubled teens like them. The conflict keeping Tony and Maria apart is also explicitly racial, which was prevalent in the 1950s and is still prevalent now. As opposed to just exploring the dynamics and senselessness of group violence, West Side Story hints at systemic causes and explanations for this violence.

The medium of a movie musical worked particularly well for translating lengthier monologues that may have appeared in the original to a more modern audience. Music is more engaging to listeners, and keeps their attention longer. My only complaints in that regard were that I didn’t personally like some of the actor’s singing voices, but none of them were awful, and the actual composition of the songs was fantastic. I’ll probably have Mambo stuck in my head for the next century or two. The faded graphics when Maria and Tony first saw each other were also somewhat distracting and just looked bad, but that’s mostly to do with the technology available at the time. They might have been better off just not doing an effect there at all.

Final Thoughts

Although there were some minor downfalls, West Side Story took the story of Romeo and Juliet and added extra dimensions to it. It navigated its world well, and it gave extra dimension and life to its characters.

Score: 8/10, closer to a 9 than a 7

0 notes

Text

1968′s Romeo and Juliet: Review

Basics

Title: Romeo and Juliet

First Released: 1968

Director: Franco Zeffirelli

Main actors: Leonard Whiting, Olivia Hussey

Plot and Script

This adaptation sticks closely to Shakespeare—mostly. None of the major plot points are changed, but Paris and Rosaline’s roles are greatly reduced. In fact, Paris isn’t even at Juliet’s tomb in Act V, and if he does die, it’s not on screen. This also changes the likely death count of this adaptation to four instead of six, since his servant isn’t there to get murdered, either. As for Rosaline, she’s only mentioned sparsely in Act III, which does cut into Romeo’s character a bit. Him moping about her in Act I establishes that he’s maybe a little bit fickle, but that didn’t make it into this adaptation. There are also several lines that were cut for the sake of time. The second half of the prologue, for example, was entirely sliced out. But also, these changes make sense. Movie watchers aren’t quite as used to lengthy monologues, and if they were preserved, it would take the movie to about the three hour mark. And sure, I would probably watch that, but lots of other people wouldn’t. It just wouldn’t be marketable at that length, and most of my personal favorite lines (and the ones that are particularly iconic) were preserved. The few lines that weren’t in the original script were still Shakespearean, and they flowed with everything else. If I hadn’t been occasionally checking the play’s script while I watched, I probably wouldn’t have even noticed that they weren’t in the original.

Characters

Every teenage character in this adaptation is distinctively teenage, and it really works. Romeo and his friends laugh and sing as they break into the party, and they laugh even more when they try to find Romeo afterwards by yelling his name. When Romeo and Juliet meet up to get married, they kiss each other so often that Friar Laurence stands between them to make them stop for five seconds so that they can actually, you know, get married. Even during the Mercutio and Tybalt fight, everyone is laughing right up until Mercutio dies because they think it’s just a joke. Seeing all of this serves to make the tragic parts of the play more tragic, since the audience has already seen that they’re still young and innocent and free. However, this means that Romeo and Juliet both cry a lot, and their weeping was right on the edge of melodramatic in Act III and IV. So while it mostly works, it does have its downsides.

Juliet in particular was incredibly well-acted here. All of the props in the world to Olivia Hussey. There’s a distinct tension in her shoulders around her mother, one that hints to the strained relationship between her and her parents before it blows up. This also shows up in her first interaction with Romeo, her first real disobedience, but it eventually melts away. She’s sweet and warm around Romeo and the Nurse, but she never compromises her principles. She refuses to be with Romeo until he marries her, and when the Nurse suggests that she marries Paris after Romeo’s banishment, she cuts out one of her dearest allies because she’s not going to give up on him, and the acting makes it clear that she doesn’t hesitate in this decision or regret it. It makes her a deep, formidable character. And Romeo is just endearingly earnest. His friendship with Friar Laurence makes both of them better characters, and was also just funny. The Nurse, Mercutio, and Lady Capulet were also notably well-done; everyone else did okay. There were no bad performances, I think, but because of the time that it was made and the fact that Shakespeare is hard to act, there were a few lines that came off kind of stiff and awkward. It wasn’t often enough to totally take me out of it, though.

Style and Medium

I don’t think this adaptation would have worked nearly as well if it wasn’t on film. This really stands out to me in Act I, where Romeo and Juliet walk around the audience while a man sings, playing a visual game of tag right up until they finally speak to each other. If we couldn’t see the camera cut to their faces and highlight their movements and were instead watching it on a stage, it would be much harder to grasp what was going on. But these cuts clarify, and they allowed Franco Zeffirelli and the film crew to really emphasize the emotions of the main characters. This was occasionally at the expense of more minor parts, but it heightened the main action.

Another benefit of film is that they could go all in with the music. Plays don’t typically have a soundtrack, after all, but movies do. Nino Rota (the man who composed the soundtrack) went for a more classical feel to match the mood of everything else happening in the film, and the melody from the song that plays when Romeo and Juliet first meet appears multiple times. Not only is it just incredibly beautiful, but it winds up having a sort of Pavlov’s dog effect, where by the end, you hear those notes and know that something’s going to happen that pulls on your heartstrings. That wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t been so well-placed throughout, but it was.

The costuming here was also excellent. Everything had a distinctly Italian Renaissance look to it, but what really stands out is the color coordination. The Capulets are always dressed in reds, yellows, and oranges, while the Montagues appear in more cool colors throughout the play. The Prince, as the neutral party, usually is wearing brown. And while the symbolism there is a little heavy-handed, it creates some powerful moments. Juliet’s rebellion shows up in her wardrobe and her actions; from the moment she marries Romeo, she starts showing up in purples and greens. The only exception to this is in the final scene when she’s in her funeral outfit, something that her family picked out for her. But where this really hits home is the final scene. After years and years of division, fighting, and aggressive color coordination, every living character is wearing black. Grief and pain has touched all of them, and with everyone in the same color, there’s no more division. It hints to a future where the fighting is over, and ultimately, Capulets and Montagues exit the funeral together.

Final Thoughts

This adaptation was solid. It hit the major notes of the story in a traditional way, one that was probably not too far off from what Shakespeare’s original audiences would’ve seen. However, it wasn’t just a recorded play. It used the strength of its medium to enhance the story, even if they also did have to cut a few things (and characters) out.

Score: 7.5/10; closer to an 8 than a 7

10 notes

·

View notes