Text

People talk about the surprise albums from people like Taylor Swift or Beyoncé that drop with zero warning but I have just been existing in this world where every album I've ever heard in my life has been a surprise album because I didn't know that musicians had schedules that we could see

142K notes

·

View notes

Text

Girl you need to get out of bed faster than this

177K notes

·

View notes

Text

*me talking to a guy with a penis* listen here, penis boy.

54K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rebecca Myers has dedicated her life to trying to change the most brutal of Britain’s serial rapists and abusers. When people hear that, they always want her to reveal the “worst” thing she has heard.

Go on, they say, as though it’s an episode of The Killing or CSI. Myers, who is a forensic psychologist working with deviant criminals, will give away a few things, such as the fact that she can’t look at a table knife casually left in the butter over breakfast after her prison housed a man who stabbed his girlfriend in the bath and left the knife behind, stuck in. Or that the theme tune to Coronation Street gives her chills. One of her first cases was a man who went on a three-year raping spree, breaking into the homes of single women while wearing an animal mask. On one occasion he hid behind the sofa of his next victim in his terrifying costume as she, oblivious and happy, watched her favourite soap opera.

The actual worst thing? She won’t tell me that — she is scared it will contaminate me too. “I have never told a soul, and never will.” That’s her job, to suffer so that others don’t, to save other women.

One of the worst things she has heard wasn’t exactly a crime. It was after a lifetime of getting into the heads of these men through a gruelling and expensive rehabilitation programme for sex offenders that thousands of male prisoners in this country undertook over a two-decade period, at a taxpayer cost of an estimated £100 million. She personally started working with the Sex Offender Treatment Programme (SOTP) when she was 22, soon after she joined one of Britain’s most notorious prisons, known for the number of inmates convicted for sexual or violent offences. She worked with them, including the mask-wearing rapist, out of idealism and trust.

Then, in 2017, after Myers had spent 16 years on the front line of the SOTP, the results of a national evaluation came in. The SOTP didn’t work. It was abruptly abandoned. She had spent so long attempting to change people who had done horrible things, and when they were released they went out and did them again at just the same rate as the men who hadn’t attempted any change.

“It was gutting,” Myers, now 49, says to me. “Just shocking. A massive disappointment to so many people that had invested decades of their lives, totally and utterly driven by wanting to stop these people from doing it again.”

The worst thing she has heard was not a murder. It was this news that seemed to kill hope. The costs, emotional and financial, hadn’t been worth it. Her memoir Inside Job gives the reader an authentic account of what it is like to work with maximum-security prisoners, including when a headless pigeon is lobbed at her from one of the cells (ripped off with the man’s teeth?), splattering her shoes with blood. “Whore!” the prisoner shouts as Myers stares at the pigeon’s still-flapping body, its spinal cord protruding. “Slut!”

She will never know who did it, whether it was because she gave them an unfavourable parole recommendation or it was just a man who hates women. “There are plenty of them about.”

When I meet Myers over Zoom I can tell how she holds her own as one of the few women in such a hostile environment. She speaks in the North Yorkshire accent of her home town with seriousness and common sense. She began in prisons months after graduating from a psychology degree. She was, she describes, “slim and blonde”, and understandably naive. She was given a tour of the prison officers’ quarters, with pictures of topless women on the walls, their breasts covered with NSPCC stickers.

Sinister disembodied eyes press against each cell’s viewing holes as she passes. “I wish I had not worn a skirt,” she writes, and she never made that mistake again, switching for ever to work in a baggy outfit of loose trousers and poloneck covered up by a jacket, even in summer. “My face and hands are the only flesh I allow them to see.” Her psychological armour in prison is represented by her perfect nail polish, which she wears to see me too.

We agree that it seems strange, with hindsight, to think that such a young woman was the right fit for the job. Myers explains that forensic psychologists are not usually like Robbie Coltrane in Cracker — in the UK 80 per cent of them are female. In the 1990s money flooded into prison rehabilitation programmes with a surge of Blairite optimism. Britain’s sex offender rehab became an international flagship, she says. In practice, that meant an “influx of fresh young female psychologists straight out of university entering the prison to deliver programmes”.

“It’s an interesting notion isn’t it?” Myers says, pondering. “The damage is done to women yet it is mostly women trying to fix it.”

The Silence of the Lambs, featuring Jodie Foster as a student psychologist at the FBI Academy trying to outsmart Hannibal Lecter was how some of Myers’ friends conceived of her job. “It was the cool thing at the time,” she tells me. “But now I completely steer away from anything of that nature. I find crime on TV distasteful. I worry about it being glamorised. It’s as far from glamorous as you can get.

“Clarice Starling I am not,” she writes in her book. “Real-life serial killers are far less exciting and more stubborn and smelly than those portrayed in the films.”

Almost immediately she was left alone with them in unguarded rooms. “In terms of how things are portrayed on television, that is one of the biggest misconceptions,” she says. “That the men would be handcuffed, that there would be officers there. There simply weren’t. You were left on your own. I was surprised at the time.”

Was that because it was considered low risk? “I don’t think it’s low risk. In the book I describe a hostage situation with a female prison officer.”

This hostage-taking goes on for 12 hours, the “decent, kind-hearted” woman held at knifepoint in a cell by a man who had been a serial rapist of elderly women in their homes. Myers is rushed to the scene in the middle of the night and helps to assess the man as highly unlikely to surrender. The officers charge in when he begins an assault on the prison officer. “So it’s not low risk,” she says. “You never turn your back. But I didn’t question it, I just followed the culture.”

The book follows closely her first treatment group of sex offenders, including the masked rapist she names “Wayne” in the book. She is not allowed to name the prison for legal reasons, and she blurs identifying details for the sake of the victims’ families. When she first reads through Wayne’s crimes she has to vomit in the toilets. In person, though, he presents as a polite, even endearing man who likes custard creams dunked in his tea. This is a hard lesson society is still learning: sex offenders are husbands, dads, people holding down respectable jobs. Even police officers, as the Sarah Everard case showed.

Each psychologist was paired with a prison officer or two for the treatment programme, which took groups of nine men through more than 200 hours of therapy that lasted up to a year. In a twist that makes her book seem even more like a Jed Mercurio TV drama, a young Myers falls in love with the prison officer she is paired with on her first treatment programme. It’s an ill-advised romance that begins and ends in the dark hours they spend debriefing each other on what they have heard about the rape and torture of women.

It’s wrong to say the treatment had no effect, because it certainly affected the staff. Myers is covert about her personal life, but she has two children and is often talked out of overprotective parenting by her husband, who does not work in the same world. “He says: ‘It’s fine, they’re going to be OK.’ ”

A serial killer once made a joke to her about picnic blankets, how they are useful to roll up bodies. She is for ever sent into high alert by lone male picnickers. The two male prison officers she worked with are mentally scarred too. One stopped being able to give his little daughter a bath. The other, then her boyfriend, couldn’t drive past a lone woman on the street without fretting over her safety. The pair would wake up together after “murder dreams”.

One core aspect of the SOTP was trying to awaken empathy with victims, to the extent of asking the perpetrators to re-enact their crimes from the victim’s point of view. They’d use pens in place of penises, and flick water instead of urine, blood or semen. It sounds like highly risky territory. Indeed, in that first group Myers is aware that one of the criminals is becoming sexually aroused by the re-enactment.

“They were very powerful, but I think they also had the potential to be shaming, difficult and potentially dangerous,” Myers says of the exercises. “We started to see from the research that an increase in victim empathy didn’t necessarily decrease recidivism.” She spent more than 200 hours with one man who was in jail after a rape and hammer attack. He told her all the right things, and she marked him down as a success. Later she saw the man on the news, convicted of a rape and hammer attack.

“I don’t know what the answer is to stopping male violence. I wish I did,” she says.

It is a minority of released sex offenders who reoffend, but each one feels like too many. The sex offender rehabilitation schemes that replaced the SOTP have yet to be evaluated. Myers is no longer involved in frontline treatment. This gets us to the question that hangs over this book. Does she despair? Why not just give up?

“No, because we can’t just do nothing. We don’t have the death penalty, we release people. We’ve got to carry on.

“I know the research showed what it showed, but I like to believe that I have averted crimes. I have to believe that over the last 25 years I have made a difference. I have to believe that or I couldn’t keep doing it.”

That gives meaning to your life? She sets her face with determination.

“Absolutely. I do believe that people can change,” she says. She can never know a woman she saved from being attacked, she says. It could be me, it could be her even, but she hopes they exist, and this hope is the best thing about her job — which, by the way, is a question few ask. “I can’t think of anything more worthwhile.”

Inside Job: Treating Murderers and Sex Offenders. The Life of a Prison Psychologist by Dr Rebecca Myers is published by HarperCollins, £8.99

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever a male says that "females have no sense of humour" " it's safe to assume that he harassed a woman and she didn't find the situation to be humorous or funny.

773 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking about this message from me mam that she sent me back when i was in uni. it literally is just a pinprick in the tapestry of life!!

51K notes

·

View notes

Text

it's so cringe how every song on the radio by a woman is about how good she is at having sex. id make a song about being ass at sex. i twist the dick like a pretzel and bite it off that's what id sing

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

That was fast. This is going to get REALLY ugly now. My (totally layman's) predictions for what will be revealed...

The service was completely overwhelmed and winged it with treatment, follow up and recordkeeping because they thought they were doing the right thing, even though there was no evidence, because ideology.

Practitioners who were concerned were censured.

The real number of detransitioners.

Adverse health outcomes will finally put to bed the idea that blockers and hormones are totally harmless, reversible, and a matter of personal choice.

(Reasons these clinics refused to participate, even at the request of the NHS, are in a table that starts on p 300 of Cass.)

TL;DR - Gender medicine in the NHS was the wild fucking west, which they hid from scrutiny, and people are going to prison.

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

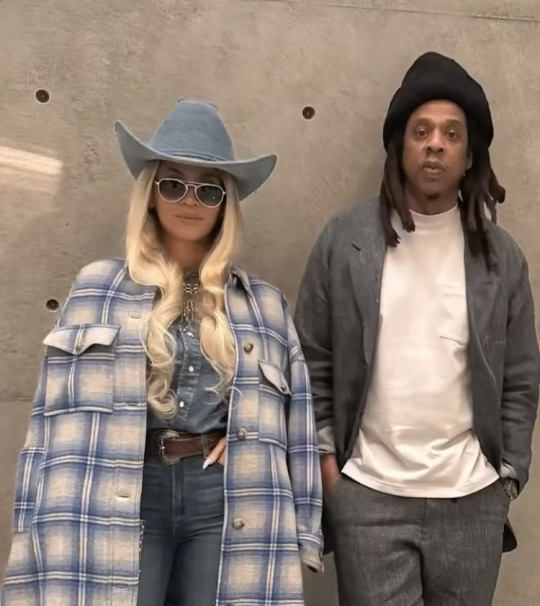

They look like 2010s medium wealthy attention seekers on a weekend trip in Santa Barbara that’s also the final straw that leads to one of them coming out as gay. He’s from SC & comes from money …she’s from pacoima but is like a genius at what she does and it’s coming to a point where he’s mooching off her. He hates that she knows more abt wine than him. Things like that build up in his subconscious and he worries since he’s approaching 50 that maybe he’s uncool..when he hasn’t been cool ever.

185 notes

·

View notes