Photo

Nov 29 is the birthday of one of the most beautiful women in the history of ballet - Inna Zubkovskaya.

Zubkovskaya trained at the Bolshoi Ballet Academy, graduating in 1941. She joined the Mariinsky (then Kirov) Ballet where she remained until her retirement in 1970. At the time, for a Moscow-trained ballerina to be invited to dance in St Petersburg was unheard of. After retirement, Zubkovskaya became a coach and worked at the theatre until her death in 2001.

Zubkovskaya was half-Jewish. Her exceptional beauty earned her the nickname “Black Pearl”.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shayna Weintraub and Sasha Zitofsky in “Uncensored,” choreographed by students of the Class of 2021, USC Glorya Kaufman School of Dance. Photo by Benjamin Peralta.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Left, Fanny Brice as Swan, courtesy the Fanny Brice Collection. Right, Barbara Streisand as Fanny Brice in Funny Girl, film still.

“The joke of a Jewish swan—flatfooted, coarse, crude—may be as funny now as it was in 1930, when Fanny Brice first skewered the classical femme ideal on film in the black-and-white movie Be Yourself. In that movie Brice spoofs Michel Fokine’s 1905 solo The Dying Swan as one of the many charades in her nightclub act, a divertissement of comic proportions in the first “talkie” featuring a female lead. The role, written for Brice and inspired by her real-life star status, follows her as she sustains her performing career while becoming a boxing manager, falling in love with a prizefighter, whom she trains with life smarts and business savvy. But as a man’s boss and not his beauty, Brice’s role picks up on the pain of the Jewish female, entirely too independent for men. This barrier in love brings added life to the Jewish swan number, as Brice’s ugly duck swan contends with this frustrated fate.

Brice’s swan, arguably the funniest among her filmic nightclub acts, embodies all that the classic swan has never dared to be. She is salt of the earth, ideal for chicken soup, and not the sweet stuff of a white swan’s weightless elegance. A bird of parody, she is the mocking companion of upwardly mobile middle-class concerns. Inverting the swan’s iconic uplift, she wades instead of glides, darts instead of developés, and is fully frank, opting for direct confrontation with audiences, when the swan figurine is supposed to be artfully ethereal, evasive—the effervescent material of fantasy and metaphor.1 A bawdy body and a dancing duck, the Jewish dying swan takes her end of life in stride, without a fuss.

Transfixing stage and screen audiences with her funny girl body, always already fallen from grace, Brice and her dying swan are a clear influence on Barbra Streisand’s rendition of Brice and her Jewish swan shtick in Funny Girl (1968), a film about Brice’s life and loss of love. Viewed together, the films make a convincing case for the swan as site of Jewish female self-reconciliation, where physical and vocal humor foreground frustrations tied to appropriate feminine codes. Made at distinct moments of American movie history that span a period of forty years, the depictions of Brice and her swan act in two films sing and dance of a female self-sufficiency that brings both pleasure and pain. A critical look at the pleasurable embodiment of enduring Jewish female stereotypes helps unpack a comic legacy of the funny girl body, unfit for love.

By foregrounding the funny dancing of Jewish swan parodies in both films, I illuminate a comic dance legacy with layered implications. I argue that ballet parodies of the white swan allow Jewish actresses to ridicule elitist pretentions of all kinds through Yiddish-inflected comic relief. In physical representations of funny women dancing ballet badly, Brice and Streisand’s Jewish swans offer duckish dance alternatives to demure femininity, much to the delight of on-screen audiences. Their comic critiques are stage show acts within film narratives focused on self-sufficient performance women. But as each film plot follows a female protagonist whose stage career overshadows her romantic aspirations, I argue for reading the swan dance scene as emblematic of larger representational dilemmas. As the funny girl body in swan send-ups invites laughter amid otherwise serious relationship dramas, she personifies a Jewish lead’s double longing for love and critical comment on womanhood. In what follows I thus question how the humor of ballet parody and the swan specifically constructs the Jewish funny girl body, adored by audiences but denied by the men they desire.”

-- from “Ballet Bawdies and Dancing Ducks: Jewish Swans of the Silver Screen,” by Hannah Schwadron, in Oxford Handbooks Online, Dance and Music, 2017.

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Ballet upholds narrow ideals for everyone: for men, the archetype of the chivalrous prince; for women, the elusive swan or sylph. Women are expected to look weightless (an image reinforced by the pointe shoe), men more outwardly muscular. Men learn to lift, women to be lifted. In classrooms, strict male and female dress codes often apply.

But within these confines, women typically face greater pressure to conform, in part because there are more of them; competition is steeper. As Pyle puts it: “If Katy Pyle is not living up to the expectations of how to be, there are 20 other young women who want that place.”

Challenging those expectations can be risky and isolating. But more celebrations of difference are emerging. Over the past year, aided by the downtime of the pandemic and the ease of meeting online in the age of Zoom, queer ballet dancers, in particular those socialized as women in their training, have been forging stronger networks and creating work that affirms they’re not alone.”

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

michaela deprince on ig

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

esteban hernández photographed performing as the bluebird in sleeping beauty by erik tomasson

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

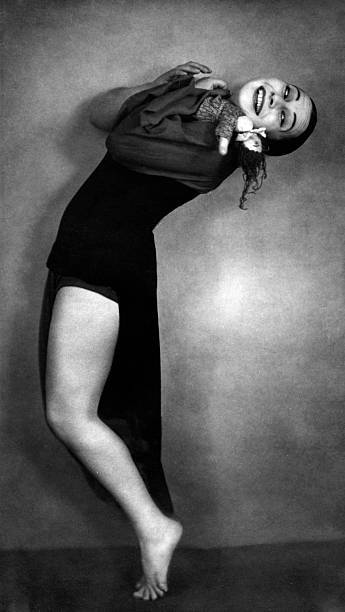

Chinese-Jewish-Latvian dancer Tatjana Barbakoff in the 1920s. Photographer unknown, rights holder Ullstein Bild.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

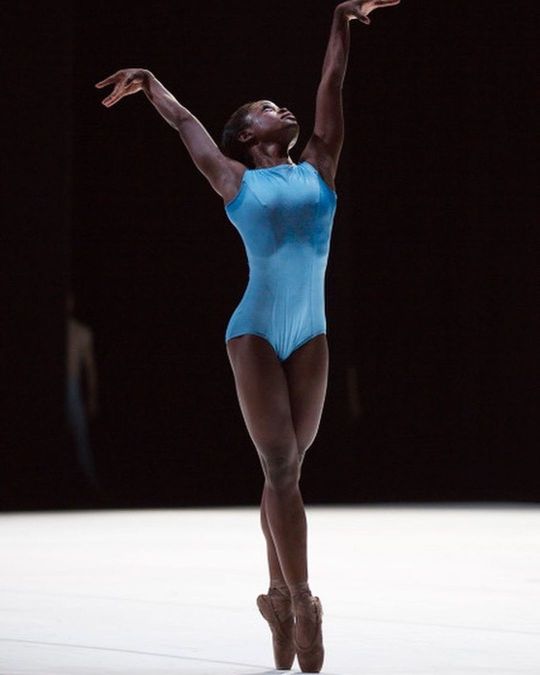

Michaela DePrince in David Dawson’s ‘A Million Kisses to my Skin’ -- photograph by Angela Sterling.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean Weidner Goldstein, photo by Heather Merriman Saba.

Jean Weidner Goldstein is the founder of the Sarasota Ballet and the Evansville Dance Theater, and an ex-principal dancer of the Stuttgart Ballet.

Born in colonial Rhodesia, South Africa, now Zimbabwe, Weidner Goldstein’s first professional position in the ballet world was in the Cape Town Ballet. What she did and how she felt about the brutal apartheid state there is not available on the Internet. There, she learned much of the Frederick Ashton repertoire, which she would later bring to Sarasota Ballet, and which now forms the basis for its reputation. She became a principal dancer with the Stuttgart Ballet in the 1970s and moved to Indiana in the 1980s, where she founded the Evansville Dance Theater and school, her first venture into directorship.

She founded the Sarasota Ballet in 1987 as a “presenting” organization, and solidified its status as a resident company in 1990 by hiring Eddy Toussaint as artistic director and incorporating many of his dancers from the Ballet de Montréal. (Another Jewish-American woman, Irene Opher, played an instrumental role.) The Sarasota Ballet’s community outreach program for underserved students, Dance -- the Next Generation, was founded concurrently, and today provides dance education and scholastic support to 150 students. As of 2019, the SB employs 37 dancers and 8 apprentices, and also maintains a Studio Company.

The Sarasota Ballet is perhaps best known for its large Ashton repertoire, unusual outside of the UK. Many of these ballets were acquired by Weidner Goldstein, and many more were first staged by the current AD, former Royal Ballet principal Margaret Barbieri.

In 2021, Weidner Goldstein made a large legacy gift to the Sarasota Ballet, earmarking funds for the Dance -- the Next Generation program and pre-professional development. She serves as Chair Emerita.

Further reading: Sarasota Ballet timeline, Sarasota Herald Tribune interview, re: the legacy gift, SCENE Magazine interview

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

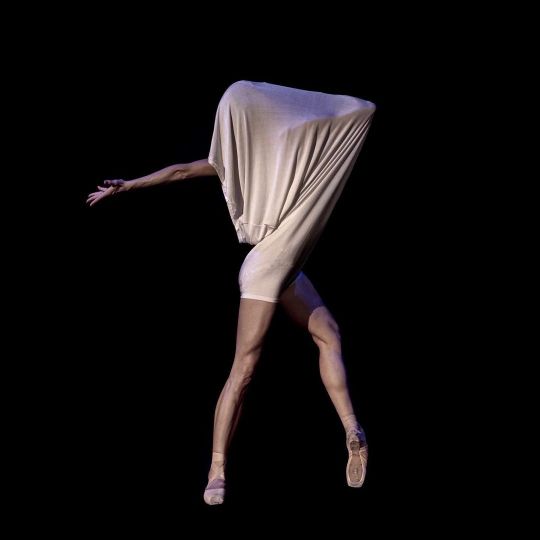

Elizabeth Cohen of the Ballet Contemporani de Catalunya in a work choreographed by Miquel G. Font. Photo by Manel Cusido.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

Chelsea Adomaitis (center) dances with Sarah Thomson and Elle Macy in Twyla Tharp’s Waiting at the Station for Pacific Northwest Ballet.

9 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Times of Israel: What would you say is Jewish about your work?

Adam McKinney: My overarching artistic goal is to create art from a place of questioning inaccurate oppressive historical perspectives of others and, in turn, ourselves.

I work toward what I call the “aesthetics of liberation” or shichrur, offering new opportunities of creating and artfully repairing a just world. My academic and artistic works reimagine memory, time — past, present and future — and public and private space by focusing on connections of bodily entities. Through this reimagining, I use the lens of contemporary dance performance to stimulate dialogue about the issues that are important to our communities. In my opinion, this is the place from where lasting change can grow.

(Source: https://www.timesofisrael.com/drones-onstage-choreographer-waltzes-across-genre-media-and-technology/)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Boris Eifman photographed by Mikhail Metzel.

Boris Eifman (1946--) is a Russian-Jewish choreographer and the artistic director of Eifman Ballet in St. Petersburg. A sometimes critically divisive figure, his choreographic work (what he calls “Russian psychological ballet theater”) tends towards the tempestuous and dramatic. Usually plotty, often based on historical events or literature, his ballets feature complex, gymnastic pas de deux and large ensemble pieces. And anyway, he’s got that Benois.

Eifman’s parents were both Ukranian Jews, but he was born in Siberia and grew up in Kishinev, Moldavia, where he trained as a ballet dancer, graduating from the Kishinev Ballet School in 1964 and dancing professionally for a few years. Subsequently, he studied choreography at the Leningrad Conservatory and founded his own company, then called the Leningrad Theatre of Contemporary Ballet, directly after. At the Conservatory, Eifman was tutored by Soviet-Jewish choreographer Leonid Yakobson, whose own fiery, dissident ballets won him no acclaim from the Soviet government. Unlike many other Soviet Jews, Eifman never changed his name or fled to America or Israel, despite antisemitic harassment by authorities. Even so, he divides his own choreographic output into three periods ("the Soviet period, the perestroika era, and the last 10 years") based on its relationship to the political climate at the time of its creation. Eifman’s 21st century ballets are largely free of political censorship and are meant to be taken on the Eifman Ballet’s frequent tours.

These tours are a hallmark of the Eifman company and have introduced his work to audiences globally. They began in 1989, with a trip to Paris, quickly followed by a tour to Israel, which resulted in the piece My Jerusalem. My Jerusalem is one of his only pieces that explicitly deals with Jewish themes, but Eifman says of himself and his work: “Every artist harbors in himself the memory of his ancestors, and I am not an exception — hence the tragic conception of my art, the striving for philosophical comprehension of life, and sincere religiousness. But my privilege is in the combination of my Jewish soul, my ineradicable desire to know the Truth, and the great Russian culture.”

Eifman’s notable works include My Jerusalem, Rodin, Tchaikovsky: The Mystery of Life and Death, and Anna Karenina.

Further reading: NYT profile 2007, LA Times profile 2015, Eifman Ballet website, Red Giselle review

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jordana Daumec, First Soloist of the National Ballet of Canada. Photo by Melika Dez.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dan Ozeri of the Polish National Ballet. Photo by Bianca Teixeira.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

“In this special episode moderated by Ellen Sorrin, Director of the Balanchine Trust, San Francisco Ballet Artistic Director and Principal Choreographer Helgi Tomasson is joined by Patricia McBride and Jean-Pierre Frohlich to discuss the life and choreography of Jerome Robbins, in honor of his centennial.”

0 notes

Photo

Adam McKinney, photograph by Andrew Eccles.

Where to even begin! I believe I shall let McKinney introduce himself, via the medium of his comprehensive Texas Christian University bio: “Adam W. McKinney is a former member of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Béjart Ballet Lausanne, Alonzo King LINES Ballet, Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet, and Milwaukee Ballet Company. He has led dance work with diverse populations across the U.S. and in Benin, Canada, England, Ghana, Hungary, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Mexico, Palestine, Poland, Serbia, Spain, and South Africa. He served as a U.S. Embassy Culture Connect Envoy to South Africa through the U.S. State Department. Other awards of note include a Mid-America Arts Alliance Interchange grant for Fort Worth Lynching Tour, an augmented reality bike tour and dance performance around Fort Worth to remember a history of lynching; the NYU President’s Service Award for dance work with populations who struggle with heroin addiction; grants from the U.S. Embassy in Budapest and The Trust for Mutual Understanding to work with Roma youth in Hungary; a Jerome Foundation grant for Emerging Choreographers; and a U.S. Embassy in Accra grant to lead a video oral history project with a Jewish community in Sefwi Wiawso, Ghana. He was a School of American Ballet’s National Visiting Teaching Fellow, an opportunity to engage in important conversations around diversity and inclusion in classical ballet. Named one of the most influential African Americans in Milwaukee, WI by St. Vincent DePaul, McKinney is the Co-Director of DNAWORKS (www.dnaworks.org), an arts and service organization committed to healing through the arts and dialogue. He serves as President for Tarrant County Coalition for Peace and Justice, a Fort Worth-based social justice organization. He holds a BFA in Dance Performance with high honors from Butler University and an MA in Dance Studies with concentrations in Race and Trauma theories from NYU-Gallatin.”

I could not have conveyed all that excellence nearly so concisely! Today mainly a choreographer and teacher, McKinney seeks above all to interrogate shared humanity, spur connection through conversation, and “create art from a place of questioning inaccurate oppressive historical perspectives of others and, in turn, ourselves.”

McKinney does this by engaging deeply with place and embodied memory. The above-mentioned project on lynching draws out the buried histories of locations within Fort Worth, Texas via the body, thereby connecting the past to the present through the dancing body. Meanwhile, his “HaMapah/The Map” revisits the sites of his Jewish ancestors’ lives in Poland and the U.S., crossing national borders and, in his own dancing person, revealing the coherence of memory and descendance. Similarly, McKinney’s work with the Surdna Foundation at the U.S.-Mexico border engages with related questions about nationality and connection, and what the arts might do to ground political will in the body. The theory and practice of his dance reveal the specificity of McKinney’s own Black, Jewish, and Indigenous (Blackfeet and Cherokee) family history and heritage, while also inspiring questions and dialogue about human complexity and connection.

Much of McKinney’s work can be found online --the wonders of profiling a modern choreographer-- and it is well worth seeking it out to help configure the jigsaw pieces of the past into a more just, and beautiful, present. You can also support DNAWORKS here.

Further reading: Academic CV, Times of Israel interview, TCU faculty profile, MoBBallet entry, Shelter in Place (aka the sukkah ballet) review, long interview with Caroline Calouche & Co. / CLT Cirque & Dance Center, McKinney discusses his relationship to Indigeneity at Indian Country Today

1 note

·

View note