Text

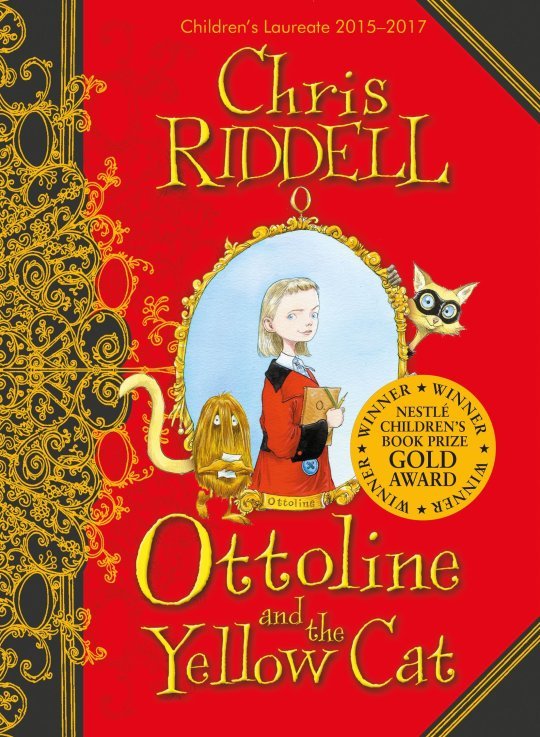

Ottoline by Chris Riddell

This series from former Children’s Laureate Chris Ridell presses several of my parenting buttons. For a start, these hardbacks (a less spectacular paperback version is also available) are things of beauty. They are books that celebrate books, with the retro faux-engraving recalling a time when reading was the height of childhood entertainment. Inside, each volume has a delightful easter egg attached to the back cover – a postcard collection (all drawn by Riddell), Bog Goggles that reveal a secret illustration, slightly wicked school achievement stickers and a fortune teller (not sure what that one actually is as the four-year-old appears to have lost it).

No wonder kids are turning their backs on e-books. These are serious artefacts to be seriously treasured.

Yet, for their proud bookishness, there’s an appealing sense of multimedia to these tomes. Riddell’s playfully extravagant illustrations carry more than their fair share of the storytelling, while adding the sort of fantastic comic detail that rewards hours of poring over his panels. At a glance they might be mistaken for a juvenile graphic novel, complete with speech bubbles and footnotes.

Instead, I feel they offer a bridge from picture book to first novel: thick enough to give the young reader a real sense of achievement in journeying from cover to cover, but sprightly enough to make this journey a fast and unstintingly pleasurable one.

Ottoline Brown

I’ll say more about the multimedia element below, but first let’s talk about the series’s star. Ottoline Brown lives alone, more or less, on the 24th floor of the Pepperpot Building, in a city that might have been designed in collaboration with Fritz Lang and Tim Burton. Her professor parents are forever overseas, collecting all kinds of improbable objects.

Ottoline is kept company by Mr Munroe, a hairy troll from Norway who is part Dr Watson, part Snowy the Dog. (Actually, the relationship between these two is surprisingly complex and affecting, reminding the reader that even the strongest friendships must navigate the odd rough ocean or two.)

The four books see Ottoline (whose notebook is full of bold ideas and clever plans) undertake adventures across several different genres. The first is a quirky detective story involving a petnapping racket, the second is a transcontinental quest, the third a sort of science fiction ghost story in a school and the last a high society mystery-romance.

Ottoline is clever, self-sufficient and well-educated, living the kind of life that probably seems extremely attractive to a child. It’s a luxurious, urbane and somewhat bohemian existence, with no parents around to cramp her style, although she is well cared for by kindly-if-distant staff. The only chore she has to undertake herself is the laundry and she seems only to do that so she can eavesdrop on the neighbours and chat to the bear who lives in the basement. She is a Mistress of Disguise, who enjoys dressing up in flamboyant attire and collects unusual shoes (one of each pair).

Pleasingly, she is far from infallible. She has a tendency towards distraction and self-absorption and seems drawn towards friends who are even worse on both counts. But these are the sort of shortcomings that come with being the hero, whose duty must lie ultimately lie with furthering the plot.

Mostly, I love that she is an intellectual adventurer. A self-reliant eccentric with undeniable sartorial flair. This is the sort of role model I want for both our girls.

Listen Again

If I’m honest, though, the thing I probably love most about these books is the accompanying audiobooks, energetically performed by Roni Ancona. I have to put my hand up and admit that I didn’t actually read the fourth book until Child One had read it by herself (with help from Roni) several times. She’s still a pre-reader, but I feel working through these books alongside the audiobook has helped her confidence (and made her feel a little grown up). Many is the morning when she’s woken early that we’ve plonked her in the other room with Audible and an Ottoline book and she’s been kept happy for a good hour or so while we doze.

I’ve noticed that her patience with reading (or, rather, being read to) has increased as a result of these sessions. Recently, we’ve gone on to read several short novels, many of them with far fewer illustrations than she would have expected previously. She has also enjoyed listening to other audiobooks and radio plays during her quiet time, with or without an accompanying book. There is a particular kind of stillness and focus that comes with listening to a story, a relaxation of the senses and an invigoration of the imagination.

Of course, the really good news is that the Goth Girl audiobooks, Riddell’s subsequent series, last two and a half hours.

Stepping up to Goth Girl

One last stroke of genius in the Ottoline series is that the unconventional manner in which they link to Goth Girl. In the fourth (and final?) book, Ottoline purchases the first Goth Girl book. Wordless dreams follow in which she imagines herself meeting the hero, Ada Goth.

Our young reader powerfully identified with this sense of wanting to meet a fictional character (and has subsequently expressed it in regards to other eccentrics such as Willy Wonka and Doctor Who). Books sometimes give us the friends we need – or perhaps, the friends we aspire to one day make.

The obvious trick would have been to have both series somehow share the same fictional world, but Riddell’s approach is instead a celebration of the act of reading. In reading about Ada, Ottoline makes Ada real. So real that Child One couldn’t wait to read the book for herself. (I suppose, this is much like having a trusted friend recommend your next read.)

I actually think the Goth Girl books are probably a little too dense for a four-year-old to enjoy (I’m possibly very wrong), but I love the way that Riddell has provided another bridge for developing readers.

Just as Ottoline's books help ease the leap from a five-minute read to a novella, her parting gift is to give a leg up to reading a proper novel. This is a rare series that grows with – and helps to grow – a young reader. I can’t recommend them highly enough.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

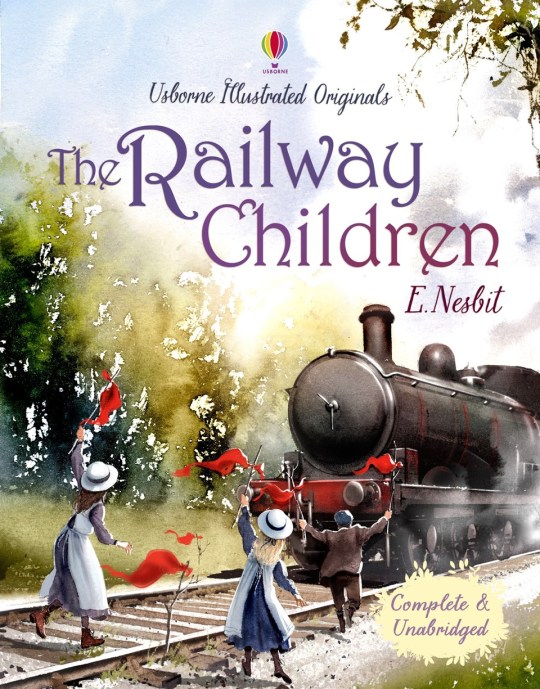

The Railway Children

I’ll confess I never read, watched or in any other way experienced The Railway Children as a kid. Which is odd because, like most children, I was a serious trainspotter (an urge that I hasn’t wholly faded, but which I’ve learned to suppress.) I first stumbled upon E. Nesbit’s tale when trying to derail Child One’s train obsession from Thomas onto more rewarding routes.

I’ve already written about Ivor The Engine, but it’s worth mentioning Graham Greene’s The Little Train (vividly illustrated by the great Edward Ardizzone), in which a branch line locomotive heads off to see the big smoke, only to realise he was happier at home.

We came to The Railway Children via a condensed Ladybird Classic, which was still a little dense for our then two-year-old. Better was a simplified Usborne version, which reduced the story to around 20 colourful pages.

Flagging and fainting

There was one page that fascinated our first daughter. It was the same image used on the cover — a young girl stood astride the tracks, flagging down a steaming engine. This, of course, is the story’s dramatic climax, in which brave Roberta and her two siblings prevent a terrible railway disaster. For months afterwards reading this, Child One would re-enact this scene, complete with Roberta’s faint once her courageous task is accomplished.

I think this moment of heroism was appealing for a number of reasons.

One, it was a rare example of a young girl facing — and overcoming — physical peril.

Two, she does so without sacrificing her femininity (more of that in a moment).

Three, it’s a recognisable, prosaic sort of adventure: even allowing for the old fashioned steam engine, the idea of having to flag down a train feels more accessible than, say, facing off against pirates or aliens.

Four, she faints.

This faint — and our child’s obsession with it — troubled me for a long while. Just as I’ve been troubled by how she enjoys re-enacting Sleeping Beauty’s century long coma (actually quite a useful performance if you have things to do around the house) or numerous princesses being chained up by evil princes or Jabba the Hutt. Given how hard we’ve pushed as parents to break down limiting gender norms, where had this fascination with oppressed (or unconscious) women come from?

The bravery muscle

What Child One was doing, of course, was displaying an innate understanding of drama. She had instinctively picked out the most dangerous, desperate moments for the characters she connected with. Which, unfortunately, tended to be when they were at their most damsel-like. A reminder, if one was needed, that representation matters.

But I’ve also come to understand the faint from a different perspective. It’s not a disappointing moment of weakness on Roberta’s part, but a reassuringly human one. Heroes, particularly heroes in children’s stories, are expected to be flawlessly brave. This approach paints bravery as an innate characteristic. You are born a hero, with reserves of courage that will allow you to overcome whatever hardship a storyteller should put your way.

Even as a child, while I liked to fantasise I would be as brave as Batman or Doctor Who, part of me feared that I wouldn’t. In a moment of crisis, I would discover my reserves or courage were empty.

What Roberta’s faint suggests instead is that bravery isn’t innate, but an exercise of will. Just as you can force yourself to run faster to win a race, collapsing in a breathless paroxysm at the finish line, you can force yourself to be brave – and fold into a heap when your job is done.

Roberta is a hero not because she is naturally braver than her siblings (including brother Peter), but because she identifies the necessary course of action and exerts muscles of courage we all possess – and might develop further with practise.

Feminine and fine

I said above that it’s important Roberta doesn’t sacrifice her femininity in her moment of heroism. This is a complex point which I’ll attempt to do justice. On the face of it, this is reinforcing the sort of tired gender norms that I strive to avoid in parenting.

But I’ve also seen how, from the moment she first opened a book, Child One would immediately identify the (usually scant) female characters. She was looking for people who looked like her. This has meant a lot of identifying with characters who are passive princesses, fantastically evil fairies or simply mute. People who get chained up or should be chained up. Once again, representation matters.

Due to the Edwardian setting, Roberta is recognisably — stereotypically — feminine. But this doesn’t prevent her being the most sensible and heroic character in the story.

There is a temptation when resisting gender norms to (often inadvertently) dismiss feminine archetypes as being inherently inferior to their male equivalents. When a female character becomes a hero she is required to essentially become more like a man. In The Famous Five, George is far more proactive than Anne, but she isn’t really identifiable as girl. Indeed, she longs to be considered a boy and insists on having her hair cut short in the hope that people will mistake her for one.

I absolutely don’t mean to suggest that women should be feminine. Gender is a construction, after all. (I should add that George is my favourite member of the Famous Five). But I worry the way we often tackle this is to privilege masculine characteristics simply because they are more associated with agency. Heroes are masculine, therefore you need to be masculine to be a hero. Roberta is proof that you can be a girl — complete with the affectations by which our society identifies one — and still be a hero.

A new family

Indeed, much of the appeal of The Railway Children lies in its strong (and rare) female focus. Although set prior to the Great War (I try not to think what might have happened to Peter in the years that followed the story), there is a sense of life in wartime here. The father has been sent away (in this case wrongly imprisoned), leaving the women to fend for themselves. And fend they do.

Roberta keeps the household together and ultimately rescues her father, but her mother is far from passive. She’s an appealingly complex character, whose great pragmatism does not prevent her from living a rich creative life. Having moved the family to a cheaper, rural existence, she supports them by writing stories for publication. She, like her daughter, is an intellectual.

It would be easy to criticise the story for its outdated values, particularly in relation to ideas of class, or its portrait of a monochrome little England. But I feel its antique mores are largely confined to set dressing, while the themes of familial love and responsibility don’t require too much stretching to fit our modern world.

Some might also find the story somewhat slight. Not a lot happens. What is most remarkable about Roberta’s moment of heroism – the dramatic climax – is that it happens halfway through the book. But I think peril and drama is often overrated in children’s fiction.

Consider Swallows and Amazons, an adventure story where there is no danger at all. Instead, the action revolves around an imagined conflict, a war game between two friendly tribes of sailors. I think that sort of gentle adventure speaks more powerfully to kids than we realise. The stakes are somehow more vivid for being smaller.

The Railway Children has its moments of high excitement, but privileges connection and character over incident. A mystery is solved, a danger overcome, yet the most important thing that happens is that a family learns it can rebuild a shattered world. In losing a parent (if only temporarily), the children discover their own strengths, look outwards, and reshape their family into a stranger, stronger community.

The Book

There are countless editions, but I recommend the Usborne versions. There are three and we’ve read them all at different ages and stages. The first, illustrated by Alan Marks, is the simplest, easily read within five minutes. There’s then a slightly more complex version of this adaptation, running to around 25 minutes and split into chapters. The big lure here is that this edition comes with a CD of the audiobook, which helps your child read the book for themselves (I’m a big fan of audiobooks and the Usborne series are tremendous). We’ve also purchased Usborne’s unabridged edition, which contains a different, somewhat prissier set of illustrations.

On screen

There are three existing screen adaptations, all of them starring Jenny Agutter. The first is a black and white BBC series from 1968, which is more than a little creaky. The most recent is another TV adaptation from 2000, which didn’t grab me. For me, the 1970 film (starring Bernard Cribbins as Stationmaster Perks) is the definitive. Beautifully shot in warm Technicolor (the blu-ray has a stunning transfer), it boasts a flawless performance from Agutter as Roberta. Child One has watched this at least half a dozen times and none of us is tired of it yet.

On audio

There’s a fantastic two part BBC radio play from 2006, which has kept Child One busy for a couple of hours at a time. Simple narration makes it easy to follow, even for younger kids.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

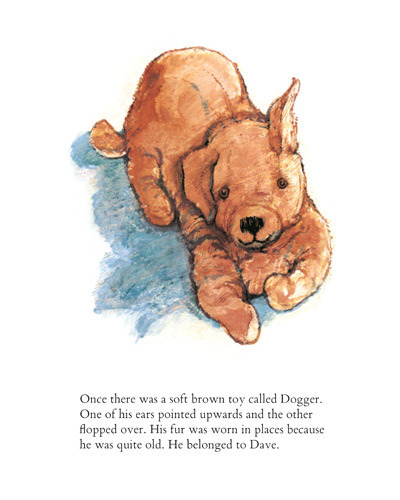

Shirley Hughes

When it comes to bedtime (and morning and afternoon) reading, I’m not sure I’ve enjoyed sharing any author’s work more than Shirley Hughes. Undoubtedly, part of this is due to nostalgia on my part. Her Dogger was probably the book I read more than any other as a child and one of the first books I bought as a parent. The nostalgia here is twofold — for the remembered pleasure of discovering her books, but more so for the seemingly lost world they depict.

It’s a cliched lament for parents to yearn for the apparent simplicity of their own childhood, but I get a real pang looking at the screen-free days, large backyards, intimate neighbours and kerbside games on show in books such as Moving Molly and Alfie Lends A Hand. If Hughes’s time machine has a particular power, that’s largely due to how vivid and real her work seems. Part of that is down to her illustration style. At a glance it might almost be called unpretty, but there is something unusually tactile to her slightly scruffy figures and the furiously detailed backgrounds. Her characters and settings almost feel more familiar than those from my own memories of childhood.

While I often transposed myself into the characters of books I read as a child, I don’t think I ever felt that books were about me in quite the same way as I felt Dogger was about me. That wasn’t entirely because protagonist Dave is a good spit for my four-year-old self. It was because Hughes conjures an emotional life for her child characters that is almost unparalleled in the world of picture books. The dramas here are perfectly sized. There’s terror as Alfie accidentally locks himself in the house with Mum on the street, or grief as he loses his pet stone, or excitement when the roof leaks while he’s at home with a babysitter. Molly comes to terms with an unfamiliar environment. Carlos wishes for a new bike, but finds joy in not getting what he wants. Dave, of course, is heartbroken when he thinks his lost toy dog is gone forever.

I’ve seen both our kids connect with these simple dramas and the complex emotions they elicit. It’s easy to underestimate the trauma wrought on young minds by apparently trivial upsets, but Hughes has an extraordinary empathy for the children she writes and draws so beautifully. Everything is an adventure, everything matters, and everything can be dealt with – by determination, negotiation, patience or resilience.

Dogger

This was a – if not THE – formative book for me (like myself, it has recently celebrated its 40th birthday). I suspect it still informs my worldview in ways I can’t entirely pinpoint. It’s a story about loss that ends up not quite being a story about loss. When collecting his older sister Bella from school, Dave loses his favourite toy and best friend — the eponymous Dogger. Mum and Dad search everywhere, but Dogger is nowhere to be seen. At the school fair on the weekend, Dogger turns up on one of the toy stalls, but Dave doesn’t have enough money to buy him back. He runs to Bella for help, but not before Dogger has been bought by somebody else.

This book is such a rollercoaster of emotions. Indeed, so profound was its effect on my young heart, that I had misremembered it as a tragedy. While the (spoiler) happy ending brings a sense of great relief, the gutpunch moment is the display of sibling love on the part of Bella, who sacrifices a toy of her own to save Dave’s Dogger. This is all the more moving as it follows a bout of resentment on Dave’s behalf towards Bella, as she is having a much better day than he is. There’s such a closely observed honesty to the line: “At that moment he didn’t like Bella much either because she kept on winning things.”

Hughes was apparently inspired to write Dogger out of fear one of her children would lose their most precious toy (Dogger actually existed, but was never lost). It’s a recurring nightmare for this parent too. Child Two has gone through half a dozen foxes (we prepared for this eventuality), whereas Child One was once briefly separated from her Pooh Bear (who has no understudy). When that happened, I oddly found myself more worried about the Bear than the child. We could have persuaded her to accept a substitute, but I’m not sure I could have lived comfortably with the knowledge that the original bear was out there, wondering why his best friend had never come back for him.

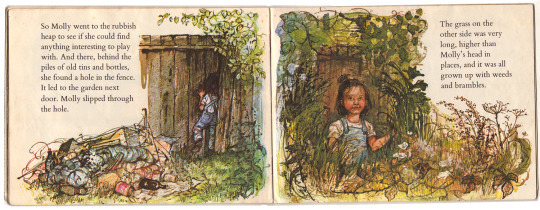

Moving Molly

This was a recent, timely discovery. We had to move twice in the space of 12 months, which was a bit traumatic for all of us, not least Child One. This book was a salve for her feelings of dislocation and uncertainty. Molly’s family leave behind a basement flat in the city for a large house in the middle of nowhere. While she likes having her own room, she misses the busyness of the city and her neighbourhood friends. Left to her own devices (a luxury children had in the 1980s), she discovers an overgrown garden next door (hints of The Secret Garden) and conjures up a raft of solitary adventures. It’s a simple tale that acknowledges loneliness and boredom, while assuring the reader they already possess the equipment to overcome. Life doesn’t stand still for long; it’s up to us to make what we can of it. I particularly enjoy the double-page spread (not pictured) in which Molly’s reality is paired with a number of imagined adventures.

Trotter Street

This anthology series follows the exploits of a group of kids from a London street. While Hughes generally seems to focus on white, probably middle class characters (I hasten to add that her illustrations and supporting characters always depict a multicultural Britain), here she broadens her scope somewhat. Characters such as Carlos – who lives in a council house with his brother and single, working mother – are from more diverse backgrounds.

Actually, it’s worth noting that all her books depict a reasonable array of different sorts of families. While the mother is usually the primary caregiver, I never had a sense of her worlds being afflicted by rigid gender roles. I’ve only tracked down four books in this series, but suspect the original intent was to explore the sort of characters and situations that often exist at the periphery of her stories. As it is, these are great tales, possibly aimed at a slightly older audience than Dogger and Alfie, but nonetheless devoured by our (then) three-year-old. She was particularly inspired by Angel Mae, who enjoys her stage debut in the school nativity play as the “Angel Gave-You.”

Alfie

These are such a rich collection of stories. It’s a treat to be able to see Alfie grow and his relationships with friends (notably bad boy Bernard) develop. Likewise, sister Annie Rose goes from being a bit part baby to an involved and troublesome toddler. It’s probably Hughes’s most elaborate world, with the neighbours portrayed as vividly as Alfie and co (one of the stories deals rather beautifully with the death of a neighbour’s much loved moggy).

What I think I like most about these tales is the focus on relationships — friends, siblings, parents, friends of parents, neighbours. In Alfie Lends A Hand, Alfie has to negotiate his own unease at going to a party without Mum, while balancing the conflicting needs of two of his friends. In helping others, he learns something of his own strength. I never tire of reading these stories, although I’m grateful for the audiobook collection (read delightfully by Roger Allam, with music and sound effects) as the children’s enthusiasm for them exceeds even my own.

Age and stage: 2+

Gender stuff: Pretty great, really. While you could argue that most of the protagonists are male, there are some really well-crafted and atypical female characters throughout her work. Take Bella, for example. Athletic and pragmatic, where Dave is dreamy and sensitive. Likewise, male characters like Alfie resist the usual rough-and-tumble stereotype. Both Alfie and Dave are pictured crying without this being a reflection on the state of their masculinity.

Drama: realist, very child-centred, usually resolved without trauma.

Outdated bits: I’m really reluctant to pick out the old-fashioned bits, because many of those are my favourite bits. You could argue that the Britain pictured looks a bit monocultural by 21st century standards, but Hughes does a much better job at representation than almost any other picture book writer of her time.

Themes: kindness, resilience, bravery, compassion, disappointment, change, love, loss, friendship, community, stuffed animals.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Superheroes

I loved Wonder Woman. Sitting through Man of Steel and Batman V Superman was kind of like being made to endure a dark episode of Scooby Doo, where Shaggy’s implied drugs habit gets out of control and he reverses over Scooby in the Mystery Van. Or to put it another way, it was like going back to your favourite childhood comics and colouring them in with a black crayon.

I loved comics as a kid. I wish I still had my collection. Superman and Batman were early favourites, before I grew into the more complex dynamic of X-Men and ultimately moved on to 2000AD (I recently reread Nemesis the Warlock from the latter and heartily recommend it to anyone who likes Monty Python, Michael Moorcock, Douglas Adams and anti-hero demons with heads the same shape as their spacecraft).

I get the adolescent imperative to transform childhood pleasures into adult pursuits, which seems to inform much of the current vogue for superhero blockbusters. But there’s no question that the DC films (pretty much post-Batman Returns) have been missing the sense of wonder and imagination that made those three-colour strips so appealing to me as a kid. The basic premise that you could have a secret life — that you could be ordinary, even unpopular, but don a disguise and go off to have fantastical adventures of world-shaking importance was a source of great comfort to this kid.

Wonder

As you’d hope, Wonder Woman goes some way to restoring that sense of wonder. She is a hero whose greatest weapon (apart from her shield and lasso) is compassion. She understands that being a hero isn’t a chore, an affliction or a way to get revenge on the world, but a duty you perform because you care about your world, your society or humanity at large.

As a father of two young girls, I wish I could take them to see the new film. They’ve certainly enjoyed the Pop! figurines I brought back from the premiere. But, for all its heart, the film retains the grubby sheen of recent DC films and a focus on extended punch-ups that mean the intended market remains pubescents and above. There are also scenes of mass murder and warfare that might be confronting for younger children. Our four-year-old still hasn’t had to face up to the idea that humans kill other humans. (She’s very interested in death, particularly the deaths of rock stars such as Bowie, Eddie Cochran and half the Beatles, but I’ve so far had to put down Lennon’s death to an “accident”.) In our household, monsters either eat you or “zap” you.

So where does a superhero-loving dad go if he wants to share these stories with his offspring? There’s the recent The Lego Batman Movie, but I found that a bit too frenetic. I wanted simplicity. I thought back to my own childhood and the Christopher Reeve Superman films of the 70s and 80s. There’s an appealing innocence and brightness to them, but Christ they’re long. I’ll admit I struggled to get through the first and am yet to plough on.

Batman ‘66

For me, the Batman TV series (1966-68) was far more influential. Movies were a special treat, but television was daily fare. You could spend twenty-five minutes a day with Batman and Robin. Of course, I didn’t realise these stories weren’t straight-faced drama. Their outrageous antics felt very real to me. Returning to them now, it’s the humour that appeals.

I’m not sure what kids raised on the Nolan films will make of it, but to this adult the show’s self-aware comedy is a refreshing reminder of how much fun superheroes used to be. Batman 1966 knows exactly how silly it is and there lies its appeal. To a child, it looks like drama, because kids’ rules are different to those of us oldies. The nonsensical stories, the high stakes cliffhangers and balletic fight scenes are perfect springboards for children to dress up in a sheet and improvise their own escapades. For me, only the Burton Batmans have come close to embracing this show’s great sense of imagination and wonder.

We first watched Batman with Child One in an attempt to find some more proactive female role-models. I’d remembered Batgirl being in the show for the entire run, but she actually doesn’t appear until the third and final series. While there are undoubtedly outdated attitudes displayed by the characters around her (and the omnipresent narrator), Batgirl herself is pretty great. By day, she’s a brainy librarian (she’s shown to be at least as clever as Batman, if not more so) who seems to turn to crime-fighting for larks. She plays a pretty active role, usually investigating in parallel to Batman and Robin, and often riding to the rescue on her rather girly motorbike.

Unlike the dynamic duo, she doesn’t actually punch anyone, but isn’t above a few balletic kicks or thumping a henchman with a handy prop. The violence here is largely playful. Nobody ever gets hurt and the infamous pop-up slugs (KAPOW! etc) give the sense of the fight scenes being a game, rather than acts of anger. That said, we did have some discussion about why it was never okay to thump anyone.

Child One loves this show, although the occasional moments of peril for Batgirl have proved a little unsettling (she’s growing to enjoy feeling safely scared). A great place to start is with a 7 minute film included on the DVD and Blu-Ray set that works as an introduction to Batgirl. It was never broadcast, but is basically a pilot for a show based around her. Series Three follows on from there.

Batman: The TV Series is available on Blu-Ray, DVD, Netflix and is soon to be broadcast on SBS.

Age and stage: 3+

Gender stuff: The female characters are few and far between, but pretty appealing when they arrive. Three Catwomen, less glamorous women villains and, of course, Batgirl offer a few different roleplay options.

Drama: largely comic, with moments of tension outrageously signposted (and usually quickly resolved).

Outdated bits: The sexual politics is seriously off, whether it’s the narrator talking about “all manner of girls in Gotham City” being nurses, secretaries or librarians… or Barbara Gordon (AKA Batgirl) flirting uncomfortably with her own father.

Themes: adventure, heroism, responsibility, bravery and the importance of good grammar.

Danger Mouse and Bananaman

For younger children, there are two other superhero series we’ve enjoyed. The first is Danger Mouse. David Jason (also the voice of Toad of Toad Hall) voices the rodent superspy, who zaps around in a flying car with cowardly sidekick Penfold, foiling the plans of villainous Baron Greenback. The show has recently been remade with a new cast, at a more frenetic pace, but I was surprised how fast the early shows were. As with Batman, there are plenty of jokes (good, flat and deliberately awful) to entertain parents. In fact, it’s hard to think of a contemporaneous kiddie cartoon where the focus is so much on comedy. Compared to the staid Hanna-Barbera shows, Danger Mouse feels positively anarchic. Unlike Scooby Doo, which would generally end on an embarrassingly lame one-liner resulting in baffling laughter from its characters, this is a show genuinely packed with jokes. Every kind of joke. Danger Mouse owes as much to the knockabout humour of the Carry On films as it does to the surreal intelligence of Monty Python, with a good dose of Looney Tunes and The Goodies thrown in. There’s slapstick, wordplay, satire, pastiche, surrealism, wit and Edward Lear–esque nonsense.

Even more beloved for Child One is Bananaman. I had only vague memories of this show and watched it primarily out of loyalty to The Goodies (who voice all the characters). But it’s fantastically silly, has a suburban cosiness and is likely to encourage kids to eat more fruit. The villains are never particularly threatening, while the real hero is Bananaman’s less credulous raven sidekick. The joke ratio isn’t quite as high as with Danger Mouse, but it can work as a double gateway — opening the door not only to the world of superheroes, but that of The Goodies (which we are yet to share with the kids).

Danger Mouse and Bananaman are available on DVD. Bananaman is also available (officially) on YouTube.

Age and stage: 2+

Gender stuff: Non-existent. There is not a single recurring female character in Danger Mouse, while female roles in Bananaman are minimal (to put it politely). The recent DM reboot has gone some very slight way to addressing this.

Drama: slapstick, fantastical adventure. Some cliffhangers, but no real sense of peril.

Outdated bits: A distinct lack of diversity, with some racial stereotyping.

Themes: humour, adventure, decency, honour and the importance of fresh fruit.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kids Music: Elizabeth Mitchell

The best advice we ever received as parents was: don’t listen to any music you don’t want to listen to. Music has always been important in our household. My wife and I met while working in record stores — she wouldn’t have talked to me, let alone hired me (as she did), if I hadn’t passed the taste test. My first paid writing gig was a music journalist for Cream Magazine, back when writing about music still was a paid gig.

Minimal Stimulation

Prior to becoming a parent, limited exposure to kids’ music gave me toothache, headache and that kind of soulache you get from consuming sugar-coated plastic. Broadly speaking, my approach to parenting has been “minimal stimulation”. There’s no great psychology going on here. I just figured if I could keep the kids entertained with the least effort — in other words, the lowest possible level of entertainment (“oh look, a leaf!”)— then I would be making things easier for myself later on. You can’t easily walk back for the sort of maximal stimulation much modern kids fodder strives for.

As a result, when it came to music choices, I tended to avoid the fast-paced and frenetic. No Hi-5 or [actually, I don’t really know the names of any other kiddie pop bands]. Even The Wiggles seemed a bit energetic for my liking. We realised early on that simplicity and rhythm were key, which led me back towards reggae, ska and early rock n’ roll. Bob Marley, Eddie Cochran, The Beatles, Desmond Dekker, Buddy Holly. (I’ve since interviewed several rock stars who have taken a similar approach with their own kids.)

Get Back

Picking music for a one-year-old made me reassess the joyful magic of those early Beatles records; albums I’d previously dismissed for being trite. It Won’t Be Long, I Saw Her Standing There and Please Mr Postman got bub swaying in her highchair. (That said, Yellow Submarine was an instant favourite. We love Ringo.)

We also revisited music we had listened to growing up in the late 70s and 80s, particularly Patsy Biscoe (the “Patsy goes electric” LP is great) and the early Play School releases. Hickory Dickory and Hey Diddle Diddle, the first two Play School records are a rich source of nursery rhymes, games and playful songs. But, nostalgia aside, what makes these records so palatable for a parent is the jazzy instrumentation that relies primarily on piano and woodwind. The acoustic production is easy on the ear, but also functions as a superb introduction to musical genres including country, jazz and folk.

Folking Up

One of the things I’ve enjoyed about parenting is rediscovering the folk traditions that live on in early childhood fiction, poetry and games. But I was surprised to note that some of the more recent songs on these Play School records were written by the great American folksinger Woody Guthrie. (Driving In My Car, Little Sack of Sugar to name two).

Sensing a chance to broaden out from Play School into the wider world of folk, I went looking for Guthrie’s other kiddy compositions. This led me to Elizabeth Mitchell.

Based in New York State, Elizabeth has moved from recording folk music for adults to releasing a series of albums aimed at ankle-biters, without forgetting that at least 50% of her audience would be tall enough to ride a scary rollercoaster. The first album of hers we bought was Little Seed: Songs For Children by Woody Guthrie. In the sleeve notes, she explains that her cover of Little Sugar was intended to sound like Johnny Cash. (Other albums feature parent-pleasing selections reworking the likes of Cat Stevens and the Velvet Underground.)

Little Seed

I’m not sure we’ve listened to any album more often than we have Little Seed. What’s most remarkable about this is that I’m still not remotely sick of it. There have been times when the CD player has been left on repeat, the kids have gone off to play, and neither my wife nor I have been tempted to put something else on.

Much of this is down to Elizabeth’s voice. While it has a clarity, it also has a warmth and familiarity – a sort of lived-in quality. Many kids performers will strive to be larger-than-life, but there is no showiness to Elizabeth’s performance. Instead there is an intimacy. There is a sense that she is singing for herself, or for your family alone. This family atmosphere is helped by the presence of Elizabeth’s young daughter Storey on several tracks, allowing listeners the chance to imagine participating.

youtube

The Albums

We have probably given Little Seed to at least half a dozen other children we judge to be of good taste. (Or, more accurately, to other parents we judge to be of good taste.) I’ve enjoyed Elizabeth’s other albums almost as much. Only Catch The Moon, which she recorded with Lisa Loeb, occasionally veers on the overly sweet — to my ear, at least; the kids love that one.

Her latest record Turn Turn Turn, on which she’s partnered with Dan Zanes, is wonderful. It’s less immediate, perhaps, but it’s now the one the four-year-old asks for most often.

There’s even a Christmas album, The Sounding Joy, which further opens the door onto the folk genre. Its 24 tracks provide a comprehensive collection of folk carols, many of which I’d never heard before. Sedate and soulful, it’s as delightful in season as it is out of it. As far as Christmas albums go, only Phil Spector has a lead on this one.

Age and stage: Infant to 10 (Okay, to 40).

Gender stuff: Elizabeth’s husband Dan provides a male presence on a number of the tracks. There’s little sense of old fashioned gender roles.

Outdated bits: Elizabeth has sensitively updated a couple of tracks.

0 notes

Text

Ivor the Engine

There is a moment in most parents’ lives when their children discover trains. Having been a budding trainspotter myself — and briefly, if less glamorously, a bus-spotter — I’m at a loss to fully explain the magic that things on wheels possess. To be honest, I’m still slightly magicked.

Most magical of all trains is, of course, the steam engine. With its belly of fire and snout of steam (the mechanics of which appear reasonably and appealingly explicable to a young ‘un), it’s the closest most kids will get to coming face-to-face with a mythical beast.

Trains are also all about rules. While cars and trucks are unwieldy and unpredictable, capable of going anywhere, a train (and to a lesser extent, a bus) is confined to a fixed course. I suspect there is a comfort in that.

Signals and junctions and forks and turntables provide kids with a whole language of control. As a six-year-old, I used to plot extravagant courses with marker pen and butcher’s paper and run my Matchbox trains to a strict timetable. Clearly, I had issues.

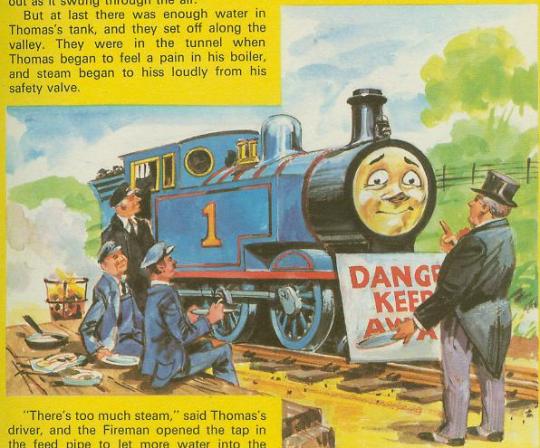

Thomas the Brown Noser

For Child One, the train obsession really took off when she was two. It sprang from her early love of books. We found a beautiful volume of Thomas The Tank Engine stories in a Chapel Street op shop, which tickled her bibliophilia and my nostalgia bone. While One enjoyed the stories (except the distressing one where Henry was bricked into a tunnel), it didn’t take me long to realise the Thomas stories are pretty seriously unpleasant.

Leaving aside the issues around gender representation (the later books attempt to redress this somewhat, but even then it’s often a female engine a) causing trouble or b) trying to prove she’s almost as good as the boys), there’s a real well of nastiness to Thomas.

The engines are constantly bickering and attempting to “pay each other out”. Their sole purpose to is to become “really useful engines” — rather literal cogs in the machine. The Fat Controller is a cruel headmaster figure, frequently delivering extreme scolding and punishments.

If you went to an English boarding school in the 1950s, it would likely feel grimly familiar. Likewise if you went on to work in a bullying corporate environment. I quite enjoyed a recent theory that argued that the Isle of Sodor is actually set in a dystopian parallel universe.

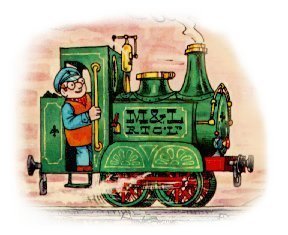

Ivor the Engine

Looking to cater to One’s new obsession with steam, I remembered Ivor The Engine. As a child, I’d had two Ivor books — The Elephant and The Dragon. Written by Oliver Postgate and illustrated by Peter Firmin (the duo behind Bagpuss, Noggin the Nog and Clangers), these lyrical tales are a perfect antidote to Thomas’s brutal world of bureaucracy, backbiting and workaholism.

In one of the stories, Ivor and his driver take the day off to go fishing. When Thomas tries his hand at angling, it nearly kills him and he learns to keep his mind on the job.

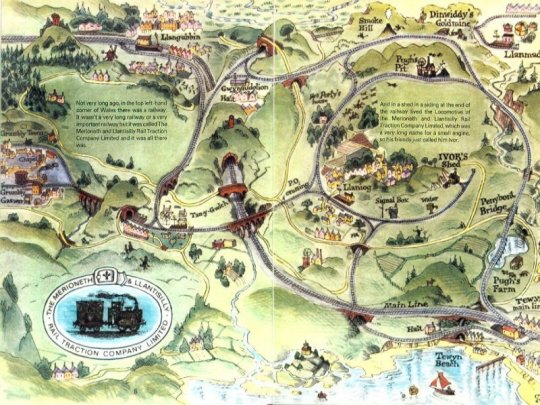

Ivor doesn’t have a face or a voice. He doesn’t even have a name (Ivor is a nickname because “the Locomotive of the Merioneth and Llantisilly Rail Traction Company Limited… was a long name for a little engine”). But through his whistled interactions with driver (and interpreter) Jones the Steam, he is given more depth and humanity than any of Awdry’s trains.

Ivor lives in rail shed attached to a railway in the top left-hand corner of Wales, a branch line that is described as being neither long nor important. When he proves himself useful, it’s as a member of the local community rather than through ruthless efficiency. He helps lure pigeons from a villager’s roof, assists a wounded elephant, saves lost sheep and runs packages to the needy up and down his branch line. When hunters threaten the lives of a local family of foxes, Ivor and Jones effect a clever escape.

While Thomas and “friends” are in constant competition to prove themselves the fastest, prettiest or most efficient worker, Ivor instead takes pleasure from his surroundings, his friends and, well, just being alive. There's mindfulness for you.

POOP POOP POOPETY-POOP went Ivor’s whistle as they rounded the bend above Llaniog. He wasn’t whistling a warning. He wasn’t whistling a signal. He was whistling for the joy of being alive and steaming, for the joy of seeing the cows in the fields and the sheep on the hills and the big wheel of the Pit spinning in the sunshine.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to see a touch of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood to the writing here, which embraces its Welsh setting through a conversational style peppered with colourful turns of phrase. Even if a parent isn’t bold enough to attempt a Welsh accent, these books are a joy to read aloud.

Rail Against The Machine

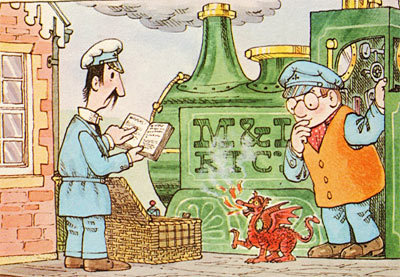

Bureaucracy is often the enemy here. In the first story, Ivor decides he wants to join the local choir, so Dai the Station has to check if it’s against regulations. (Head office ultimately sign off on it.) In The Dragon (star Idris is “not one of your lumping great fairy-tale dragons… [but] a small trim, heraldic Welsh dragon, glowing red-hot and smiling”), Dai tries to force Ivor’s scaly new friend out of his firebox and into the “proper container for carrying livestock”. Later, Idris is forced to flee from the railway after an “investigation” is launched into his existence.

“NO!” cried Idris. “No! Dragons are mythical! No, I must not be investigated! No! No! No!”

Thankfully, the local community come together to shield Idris from the excoriating gaze of authority.

Most frighteningly, Ivor himself is threatened when the owners of his railway decide to sell off to a national company that plans to replace him with a diesel. (Not quite as frightening as when Thomas’s cronies are threatened with the scrapyard.) His salvation comes not by proving himself a vital asset to the functioning of the marketplace, but rather as repayment for his past kindnesses.

There is a joy and a magic to these tales that doesn’t undermine the background texture of social realism — the mines, the gasworks, the fish and chip shop. Thomas might depict society as it often is, but Postgate and Firmin offer a glimpse of community as it should be. People who delight in their interactions, who tolerate eccentricity and who find pleasure in their work but are not crushed by the weight of material aspirations.

Compassion and Contentment

The real star, Ivor aside, is Jones the Steam. He is a man in his element, happy in himself and his work and seemingly wanting nothing more. He doesn’t aspire to be a station master or to run his own railway. Although he enjoys performing his errands, Jones’s greatest pleasure is making his morning cup of tea from Ivor’s boiler.

He is compassionate and sensitive, always keen to help, and blind to his own quirks. It’s left to us to decide whether Ivor has an intelligence (I think he does) or whether Jones merely ascribes one to him. Other characters rib him for talking to Ivor, but affectionately so. There is no cruelty here. Only once do we see Jones lose his temper, when dealing with a truculent elephant.

I first encountered these stories as books, without realising they were sprung from a television series that originally screened in the 1950s and 1960s. (The books are far from the usual afterthought cash in, each story lovingly rewritten and reillustrated by the original team.)

The colour episodes are available on DVD and were some of the first television we showed to Child One. There is an enchanting simplicity to the cut-out animation and a leisurely pace to the storytelling that makes them feel very much like a picture book brought to gentle life.

Postgate does most of the voices himself. He is a perennially comforting, sedate presence. As Charlie Brooker once wrote: “there is no more calming sound in the world than the voice of Oliver Postgate. With him narrating your life, you'd feel cosy and safe even during a gas explosion. It floated above all these stories, that voice; wound its way through them.”

The episodes are also available (in pretty terrible quality) on YouTube and, thanks to Postgate’s tender narration, make for delightful audiobooks if you leave the screen off. By a stroke of luck, I recently found a copy of ten of the stories on vinyl.

BOOKS

The Ivor books are all out of print, but readily available via eBay or Abe’s Books.

Ivor The Engine Storybook (published 1982). This is the perfect starter, containing four tales. The First Story, Snowdrifts, The Elephant and The Dragon. Hardbound. Each story takes about 10 minutes to read.

The First Story

Snowdrifts

The Elephant

The Dragon

Ivor’s Birthday

The Foxes

All released in hardback in the early 1990s.

DVD

The Complete Ivor The Engine (Universal Pictures, 2006, 186 minutes)

All the colour episodes of the classic Sixties and Seventies children's series. Enjoy once again the adventures of Welsh steam engine Ivor, Jones the Steam and the good people at the Merioneth and Llantisilly Rail Traction Company - not to mention the dragon and his chestnut barrow!

AUDIO

Ivor The Engine And Pogles Wood by Vernon Elliott

Not sure how much the kids will enjoy this, but it’s pretty delightful. Woodwind and brass score, which (like the sound effects from the TV show) has the benefit of being easily imitated by non-musical parents

MERCHANDISE

Not a lot. There’s a board game I haven’t played, some resin models of Ivor and — perhaps most tempting — a plush Idris the Dragon (not baby safe). Etsy has a few handmade treasures.

THE SHORT STUFF

Age and stage: 2+

Gender stuff: not great. There's a female vet, female shopkeepers and a batty old woman or two, but that's about it. I tend to read the dragon as female, but he's described as being male.

Drama: minimal, with few moments of tension. When younger, Child One was only distressed by the fox hunting sequence in The Foxes (spoiler: the fox lives).

Outdated bits: leaving aside the old school tech and above-mentioned gender issues, it's hard not to feel uneasy about the stereotyped Indian elephant keeper. There's otherwise a distinct lack of diversity.

Themes: community, individuality, compassion, anti-bureaucracy, mindfulness, tolerance, contentment, mythology, the wonder of steam.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I recently took Miss 3yo to this fantastic Welsh production.

“They may be digital natives, but still remain susceptible to the delights of analogue play. More than that, this was a reminder that boredom (or, at least, idleness) is perhaps the greatest gift we can give our offspring.”

Full review here.

0 notes