Note

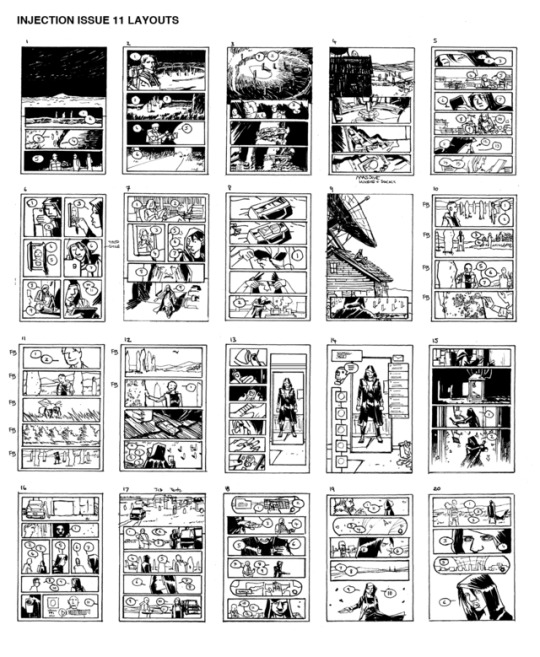

On the topic of panels - do you feel that most writers/artists have a certain standard layout they prefer? You mentioned that 8-panels-with-mergers is your standard. I've noticed that Alan Moore sticks to a fairly strict 9-panels-with-mergers. Are there other signature styles?

I wouldn’t say “most” but you can certainly spot trends. Even those who don’t like grids per se often have a panel count they tend to return to, at least in work in a certain mode.

(See also - use of splash page.)

Ennis is one of the guys who’s quietly influential on my generation of writers. He leans to five panels for page, which is one of those options that artists really like, as it allows a lot of options for them to choose with. When writing mainstream stuff, I generally lean on a five panel page as well.

Someone like BKV leans a little lighter - he is heavily four panel and heavily with splashes. The most fascinating thing about Brian’s style is that for how sparse his style is (it’s never heavily dialogue ether) is that there’s no complaints on how it works. You can see that influence on various people - I always think of Nick Spencer as someone who clearly enjoys the clean storytelling of BKV.

(I don’t think it’s quite as true as it once was - post SUPERIOR FOES he’s moved into much dense structures. In passing, THE FIX is great.)

Then there’s people who like using the three panel - Ellis does it in a certain mode, though less so recently. Millar does stuff in the three panel which just fascinates me.

The wide-screen single-tier panel was popularised by Hitch with the Authority (and then transferred to the Ultimates) and was - to my mind - the dominant style for superhero comics for most of that decade.

Honestly? If you’re thinking of learning to write comics, sit there and count panels. “How many panel transitions were in this comic” is the sort of fundamental math you have to internalise. Even now, if I read a comic that I’m surprised by how big it feels I stop and do the panel transition count.

(20 page comic. Assume 2 splashes. Average of 5 panel count, outside that. That’d be 92 panel transitions. That’s pretty high for a mainstream book, if you nose. I actually feel much more comfortable pushing my comics over 100 transitions if I can, which is pretty dense. How many moments you can show is very much how much material you can include - the whole argument over decompression is based around what you choose to use those panels for. Either less panels to increase a moment’s power, or more panels on an individual moment. Making those calls of what to priortise is literally the job.)

I like eight panel, at least in a certain mode of my indie work. It allows two-shots, assuming you don’t over-estimate the amount of dialogue that can fit - or, at least, it lets you have a reaction shot to a line of dialogue. It’s also the panel-layout closest to our eyes’ peripheral vision. It has big costs, obviously, but it works for a lot of things.

(If you’re asking for problems, there’s a few implied in there - over-estimating what can fit in a panel can cramp it.)

I got my love of the 8 panel from David Lapham’s STRAY BULLETS, which uses it amazingly.

Grid stuff? Alan Moore’s 9 panel love is pretty obvious. It’s a meticulous and demanding, structuralist form. The sixteen panel grid lies beneath DARK KNIGHT RETURNS with Millar. When I think six-panel grid, I almost always think of Kirby.

I’m sure you can spot a bunch more.

119 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could I ask what's your process for series bibles? I keep seeing references online to like a 10,000 word doc for Uber and you mentioned Spangly New Thing being 14,000 and unfinished, both of which seem significantly bigger than say, the publically available bible for Battlestar Galactica. So what is it that goes in there?

I normally quote Uber’s one at 25,000. I think that includes the cover document though. The WicDiv bible was about 13,000, but includes a lot less stuff than Uber (perhaps obviously). Spangly New Thing will be… oh, I’m really not sure. Spangly New Thing is complicated, and multifarious. I may not formally bible-ify the remaining stuff.

(I suspect Uber leans long because of my stage in my career, which was all about the Working Too Much.)

A bible, for me, is basically…

1) Background crap/what the fuck this thing is actually about.2) Character Stuff.3) Any weird stuff about the world.4) Synopsis.5) The long term plan for the rest of the book.

So the WicDiv bible would have included…

1) Top view of the book with themes, what it’s about, clever wanky stuff, background. This bit actually includes stuff like - say - the whole first Pantheon, etc.2) Big bios of each of the gods, including anything which Jamie would need to know.3) Power crap.4) A full breakdown of the first arc, issue by issue.5) An arc by arc breakdown of the rest of the series.

That I do books with big casts tends to balloon it. The majority of the WicDiv bible was character stuff, laying out everyone’s arcs.

Bibles are abstractly created for TV shows to communicate stuff about it to everyone (Some are for pitches, others are more like show dictionaries.) I think I’ve seen… maybe one bible in my life?

My Bibles are primarily for me, and only secondarily for the artist. It’s me getting the thoughts down on paper. It’s not gospel - I do tweak stuff all the time - but this is my plan of engagement and an overview of the terrain ahead.

If you want a crappy metaphor, my Bibles are the sourcebook for the campaign I’m planning to run.

96 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you ever write a lot of stuff that feels like crap but you just keep writing it anyway because you know you're biased and it's best to finish and then if it IS crap to rewrite or cut it away completely, or have you developed a fairly accurate crap-meter over time and all the stuff you've written? Also, hi! And happy New Year!

Hi! And Happy New year, etc.

Er… like most things, there’s various schools of thought on this. Did you see this Gifset about Stephen King and George RR Martin talking about work methods? And the quote attached to it from Calvino? Well, that’s a fairly hefty schism. There’s Vonnegut’s Swoopers vs Bashers too (”Swoopers write a story quickly, higgledy-piggledy, crinkum-crankum, any which way. Then they go over it again painstakingly, fixing everything that is just plain awful or doesn’t work. Bashers go one sentence at a time, getting it exactly right before they go on to the next one. When they’re done they’re done.”). Worth noting the bias in that one, of course - Vonnegut is a self-described basher, and the quotes that follow it show no understanding of swoopers.

(And from that, you may guess my bias - through that filter, I’m a swooper. I think that level of analysis of a sentence out of context is pointless. You’re writing a story. Sentences are only really good or bad depending on how they serve a larger purpose)

But binaries are also rubbish. The map is not the terrain and all that.

In other words: be careful with advice on this. This may not be you. Whatever works works. Discovering what works for you is the key thing. Maybe you lean basher. That’s fine. Being in a corner with Vonnegut isn’t a bad thing.

(No-one leaves Vonnegut in the corner, cue dance routine, we’ve had the time of our life, so it goes.)

Generally speaking, being a working writer working in a pulp corner of the media and with other people relying on me to earn money (I think it was Ivan Brandon who argued if you leave your artist without pages, you should pay their rent.) Doing the job is, involves doing the job.

You’re correct that it’s rarely as bad as you think it is.

At the same time, it’s also almost always easier to edit something than to write something. So write anything. You can always delete it. At the absolute worst, by writing it ,you’ve discovered one thing which ISN’T right. More likely, when it’s on the page you can sit back and realise what’s wrong with that take. What’s false? What’s missing? How can you change it to make it so?

That said, if something isn’t time critical, and there’s any other option, sometimes you know you’re not ready to write this, and you should press abort. In the notes for WicDiv 24 I wrote about my first draft of the first few pages. Now, that is almost identical in “story content” as what was printed, but was shit, or at least weightless. When writing it, I then stepped way back, realising I wasn’t ready to write the issue, and went and worked on other things to leave things to cook more. I just didn’t really know what was happening, on a much deeper level.

Now “I’m not ready to do this” is a good thing to lead you to procrastinate, so be careful with letting yourself off the hook too much, but sometimes you’re just not ready to do it, and you have to accept it.

But generally speaking, if you now the story, almost any tactics you can do to do some kind of first draft will be more easily edited than a blank page. Literally any tactic. Write it out of order. Write it without dialogue. Write it without description. Anything.

And now to go and try and prove this right with WicDiv 26′s script, which needs to get over to Jamie today, and - oh my! - have I some things to tweak.

106 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, page budgets? You mention them a lot, and how you innovatively save on them by printing half empty pages. I eventually worked out that this was to do with Jamie’s time rather than actual printing. Which would, you know, get more expensive the more pages you make. But I’m still confused. Surely the budget should be on a number on panels, not a number of pages? A nine panel grid on a crowd scene is going to be a lot more intensive than a splash reveal on two characters in bed, for example?

Heh. This question includes basically huge chunks of what it means to write comics which no-one ever really talks about.

(I hope to expand on a bunch of this in this seminar, actually.)

In short, you’re right to be thinking on more axis than just number of pages but you’re not quite thinking on enough axis of complication simultaneously (Or at least, Tumblr’s word county is preventing you from expressing all those axis.)

Yup, a nine panel page of a crowd is more work than a splash of a fairly simple scene. On average. You can probably think of some exceptions and ways to do it which isn’t more work, which is at least part of the point.

Any of the following (and more) increases the amount of work on a page…

More backgrounds.

More figures

More panels

More complicated story telling.

And so on.

So, for example, what’s more work? A nine panel page of talking head or a 3 panel page of a fight scene in a crowd in the middle of a city-scape?

I dunno. Depends on the artist and their choices, and recognising which is true for every artist you work with means you can think about their workload.

Because this is where the page Budget comes in. As we’ve described above, the amount of work on any given page varies hugely. However, that’s not how people get paid in most comics. You get paid on a page rate, whether or not the page is a lot of work or nothing.

So, as a writer, you try to be aware of what an average amount of work actually is on a page. You try and make sure your issues (or at least the work across the series) averages out. You try and work out ways for an artist to work out what work is 100% necessary, and which work you can try to minimise. At the absolute least, you should know when you’re asking for too much and apologise.

It’s also worth noting that an artist will be thinking of their own workload. You ask for too much and they will end up either blowing the deadline, quitting the book due to the level of abuse or just creating their own shortcuts.

In the case of Young Avengers, Jamie was doing 13 issues in the year. That is a lot of work. This is a team book, meaning there’s a lot of figures in play. Some of the enemies are fucking crowds. Ouch.

So I tried to work out some ways to help with that. The biggest one is Mother’s dimension. It’s a domain beyond reality, outside the page, outside reality. We do lots of creepy stuff with panels there. It’s effective.

It also has literally no backgrounds. It uses white backgrounds as an aesthetic choice, but also a practical one.

Equally, there’s an awareness when there’s an issue which asks a lot, you may plan for the previous one or the next one to ask for less. Young Avengers 9 and 10 - are relatively quiet. While it’s also the beat of the book, this is at least in part as I know the next issues are going to need spectacle.

It’s also worth noting that it’s not just writers who think like this. For example, consider this cover by Jamie.

This is at least twice as much work for the Matt on colours as a normal cover. Each one of the dimension slices require basically starting a new job.

The next issue…

It’s effective, but at least in part it’s giving a much easier cover.

In short: be aware of what you’re actually asking for.

Turning to WicDiv’s concept of page budgets, it’s that Jamie and I have agreed that there’s 20 pages of work in an issue. That’s basically what the advance covers, and what Jamie can do in the period. That is 20 “average” pages. We use all the above to try and balance that out. Some pages are harder than average. Others are easier than average. And we use all the above tactics to try and help with that. The basically backgroundless black of the Underground allows us to do something aesthetically effective while saving time, in the same way as Mother’s dimension. We create a crowd based character in the form of Dio but use it sparingly - plus have them in coloured silhouettes. It’s still a lot of figures, but it requires less detail than a true crowd, and we get our unique effects from it. Plus there’s the awareness of some issues being more work than others - 31 and 32 are this visual showcase, while issue 30′s extended scenes in the Underworld let Jamie catch a breath before heading into it.

In terms of my hard page trickery where I basically split a page in half and fill the rest with text, that’s an extension of the above, made possible by the fact WicDiv isn’t paid by a page rate, but rather an advance per issue. At Marvel, a trick page is normally counted as a full page for payment.

(There’s a few exceptions there - pure design page with no art don’t come out of the budget. Things like JIM’s text drops and Jon’s design elements are all “free” for the sake of the budget. In other words, if they weren’t there, they’d only be replaced by an advert. They never take away from comic art.)

As long as I can make a page half as much work as average page, I can count it as a half page… assuming everything else is balanced. The simplest trick there is having a grid and only having half the panels featuring drawing. There have definitely been times where things I’ve counted as half a page are in fact more than half a page, and Jamie has corrected me, and I’ve tried to settle the books down the line. The Dionysus fight pages in 32 are certainly half a hard page.

Anyway - when I talk about Page Budget that’s basically what I’m thinking about.

354 notes

·

View notes

Note

You (and most comics writers) juggle a bunch of projects at once, do you have any advice on how to manage that, both in a practical (e.g. scheduling) sense and in terms of making sure your brain has the bandwidth?

On the practical side…

I’d strongly advise you over-estimate how much time everything takes. You know your work-rate? Never plan to operate at your max work rate for any extended period of time.

(Me? I don’t schedule to work on the weekends. So Every 7 days I have 2 days which can be used for panic mode shit-hits-the-fan if I need to. Ideally, I don’t, which helps avoid burnout. In practise, most of my relaxation is work of a different kind, but that’s me.)

So - between the above, it means you can practically be sure you manage all this.

I plan for a minimum 5 pages of new draft (or equivalent) every day. In practise, that can change, and on a good day you write more, but that is a steady and sustainable pace which leads you to produce at least four scripts a month. Even if you’re being slow, that’s a script a week - and “A script a week” is a good and useful way to thinking about scheduling. “This week is about this.” This also helps on cognitive load…

On the Bandwidth issue…

Changing gears between projects is the hard thing. This is, in my experience, primarily in the generative side of things. In non-generative work, the load in switching between projects is much lower.

My usual day is “generative work in the mornings, all other work in the afternoon.” This is a plan, and rarely completely sticks, but if it does, it’s a good structure.

Generative work is anything entirely new - mainly first draft scripts, the aforementioned 5 pages.

All other work is obviously the usual busy work (e-mails, etc) but also includes things like edits and even polishing early drafts into scripts I can show an editor. If the underlying work is solid, I find polishing not as cognitively demanding.

(Sometimes less essential generative work goes in the afternoon too, though usually affecting it in some way. If you want a reason for messiness in my Newsletters (usually written right at the end of a work day) then that would be it.)

Returning to the switching gears in generative work, this is where you get absolutely crushed. If I’m working on one project and I have to deal with ANYTHING else from another project, no matter how small, it involves downloading everything you were doing, picking up the whole other project, solving the problem, and then reversing the process. I lost two hours to this the other week, when I had to switch from Spangly New Thing to WicDiv to give a new interstitial for issue 39. The result of all that effort was the word “LOW.” Obviously for a less demanding project than WicDiv that would be easier, but with a super-structual fucker like this god book, I need to think how it reflects with literally the whole thing.

This is the other advantage of doing things week by week. You know this week is for generating a certain project. On Monday you start writing it. You upload that project into your head. You live with it for the week. By Friday, you’ve finished it. You download the project, reset on weekend, and repeat the process next week.

197 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why is Aquaman the best?

Man, I love Aquaman–to the point where I was basically the go-to guy back in the Comics Alliance days when they needed someone to defend Aquaman–but I don’t think I could go as far as to say he’s the literal best. Like, I wouldn’t put Aquaman on a list above Superman or Wonder Woman. But I do think he is vastly underrated as a character.

Setting aside the fact that the reason most people think he is dumb is due to a misunderstanding of his powers–which creates a feedback loop in which creators then try too hard to make his powers NOT look dumb, which only makes the book actually, measurably dumber–Arthur Curry is a really interesting character that plays a role that other characters don’t.

Arthur Curry is a man of two worlds in a way that even other “_____ of two worlds” characters aren’t. Superman is an Earthling and a Kryptonian, but it is incredibly unlikely that in his adulthood, he’s going to be called back to be king of Krypton. He inhabits a liminal space in that he belongs to two incredibly different cultures, while standing apart from each of them. He was raised among humans, but his powers make him an outcast. He is the hereditary ruler of Atlantis, but his own people reject him for his human background. He protects the land from the sea, and the sea from the land. He tries to use Atlantean tech and magic to benefit land humans, and he tries to modernize Atlantean society with human political science. Both reject him. He’s perpetually stuck in the middle, yet never ceases to fight for both sides. (This, btw, is what separates him from Namor, who only cares about Atlantis.)

Aquaman as a book has the potential to be the Game of Thrones of the DC Universe, since Aquaman is basically Ned Stark. He’s the last bulwark between the monsters of the depths and civilization. He doesn’t usually get played that way.

He is also, of course, King Arthur, though that doesn’t get played up enough either. You sometimes get that connection, like in the Waterbearer era, but that was by attaching him to the Lady of the Lake and such, which is not the obvious connection. You have the rightful heir of a great kingdom who is raised in isolation from his own kingdom only to inherit it as an adult. He then assembles a team of like-minded heroes to help leverage might in service of right. This is text, this isn’t me saying, “Oh, here’s what I would do.” That’s…that’s what Aquaman is. But you don’t get the parallels to King Arthur as explicitly as you should, imo.

Also he’s friends with an octopus, and that rules.

383 notes

·

View notes

Text

THINGS THAT POINTED TO UP

- a few of my favorite things, 2017 -

Every writer gets asked where we get out ideas from time to time. As far as burdens of our field go, that I work in a field that people ask about sometimes doesn’t register as a complaint. On planes, at parties, in the waiting rooms of hospitals, I am an Interesting Person To Sit Next To, which often countermands the first impression I radiate, which is Ew Weirdo.

The answers, unless the writer in question is feeling pissy, tend towards the same-ish neighborhood of responses: “everywhere” or “my life” or “the news” or “dreams” – all leading to the generally same dénouement of “Writing is a discipline that requires a lot of work, and working a little bit every day gets you a little better every day” and so on. I think I read Stephen King sometimes claims to get his ideas from a little store in New England somewhere, for a buck a piece. But really it’s sitting down and doing it a lot until you fool someone into paying you.

OR SO WRITERS WOULD HAVE YOU THINK.

I am violating the rules of the Secret Writers Union doing this (sorry gang) but I don’t care, it was a hard year and I want to talk about good things in the inexorable march towards the new one. So here you go, cats and kittens:

The real secret to writing are Palomino Blackwing pencils.

Some will say you gotta go 602, others maybe the basic black; I myself even dabble with the pearl or even the bright blue HBs (sorta like ordering off-menu, that one you gotta find for yourselves), because why go through life with one hand tied behind your back. That’s how any of us do it. Any writer. All writers. Everywhere. We write with those pencils. That’s where the ideas come from. None of the writing comes from us, it’s the goddamn pencils, we’re like muscle-vessels and they Krang the shit out of us through the hands. We hold on and they swoop themselves across the page and when you look down, you got words and subjects and objects and predicates and shit, boom boom boom.

Even Sondheezy agrees, the only pencil worth using are Blackwings. When they went out of business the first time, he bought all the dead stock.

I like to keep away from my keyboard for as long as possible anyway; having Blackwings means having a pencil that makes me love the physical act of putting marks down on a page. That was good to have this year.

196 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Comic Writer Masterpost

I get asked of how to write for the comics form a lot, and have put a bunch of advice in a bunch of different places. I want to put it all in one place. This is a work-in progress thing, which I’ll try and add to as things occur to me. Failing that, I’ll be using a Writer Advice tag from now on so you can click that.

THE START

This is how I started. Warren Ellis’ seminal - by which I mean in its real sense rather than my usual use of “flecked with semen” (Though with Warren, you never know) - COME IN ALONE column featured a three part sequence on how to write comics.

This was my in. I still think it’s a good in for you.

(For my generation of comic creators, I’d say C.I.A. was enormously influential. If you have any interest in knowing the intellectual soup where a lot of us came from, you may want to read the whole thing. Or don’t, because you are THE FUTURE, remember, and fuck old people like you, Gillen.)

Anyway - the three parts…

Part One - Preparation

Part Two - Script

Part Three - Pitch

This is basically what I paraphrase when explaining comics to people in the pub.

Some of it is dated slightly - especially in the third part, as you almost certainly won’t be pitching like that now (though some core aspects certainly are). The core craft and discipline is 100% on point. Take this, internalise it, make it your own.

BOOKS

Warren writing above said that in his day they had it hard, as no-one wrote about comics craft. My generation had it easy, he noted, as there were some books. Your generation has it easier still, as they’re shitloads of them.

I’ll probably edit in more books here as I progress, but I want to put the core two that I think everyone needs to read.

UNDERSTANDING COMICS - Scott McLoud

COMICS AND SEQUENTIAL ART - Wil Eisner

The former will give you the basic tools to dissect comics. The latter is a master at work. Take them, internalise them, make them your own.

If you’re talking about story structure generally (i.e. not just comics), when asked, I normally recommend reading McKee’s STORY and King’s ON WRITING back to back. They are both true. They are both 100% contradictory. It will teach you the most important lesson in writing - whatever works, works, and the job is building your own toolbox.

(The secret: writing is enormous. We say “writing” and we’re really talking about dozens of skill-sets.)

EXAMPLE SCRIPTS:

The Comic Script Archive is the biggest source of comic scripts online. You’ll see how various people write the form. See what you like. There is no standard method to comic scripts, as you’ll see.

“Where can I find comic scripts” is a question I’m asked all along. You can find the Comic Script Archive as it’s the top entry on google if you enter “Comic Scripts.”

I’ll say this here as a general thing, as I’ve never said it directly to anyone: if you asked this question, you really need to up your game. If you need mentoring for that, you are not going to make it. Seriously, you can do better. Do better.

If you want to see one of mine, here’s one for Phonogram: The Singles Club. Phonogram scripts are unusual, so perhaps not one to take many lessons from - most artists will club you if you write a script like this. If you want to see me working in a more commercial mainstream stripped-back mode, there was a DIRECTOR’S CUT of DARTH VADER 1, which includes my complete script for the issue. It’s on comixology, but you can probably get it from a shop or Ebay.

OTHER RESOURCES

Decompressed: my comics craft podcast. I’ll do more eventually, probably. I go into detail with a creator over their choices with a book. “Why this panel? Why that panel?” This is basically the sort of questions you should be asking yourself whenever you read a comic for the next few years or so. As Warren says in his essays, yes, it does ruin your reading of comics for a few years, but it’s the cost of doing business.

How To Write For Space (i.e. How Comics Is Unlike Prose): An off-the-cuff piece about how I write for a set format (A 20 page comic).

Some advice I gave on pitching comics.

Kelly-Sue Deconnick on writing comics.

Warren Ellis on writing comics.

IDLE PIECES OF BULLSHIT MAXIM I SAY TO MYSELF WHICH YOUR MILEAGE MAY VARY ON

Never forget: you are a parasite. The artist does not need you.

Scripts are love-letters. They are meant to inspire the artist. An artist who is not inspired will create shit work.

When analysing comics, assume the creators had a good reason for making the choice they did. Try and work out why they did. There’s a time you can afford arrogance, and it’s far in the future . For now, assume they know more than you do. Even the creators you hate. Especially the creators you hate.

The last isn’t always true, but you’ll learn more this way. I’m suggesting stances which maximise your chance for growth as a creator at the expense of your emotional well-being.

See also : if someone can’t understand your book, it’s always your fault.

(That one will break your heart, btw)

Bear in mind the Gillen/McKelvie paradigm while analysing comics.

That’ll do to start with.

6K notes

·

View notes

Note

For those of us writers, could you take us through your daily schedule. I mean you have to be a time management wizard.

This answer is 3 years old, but the basics haven’t changed too much: http://kellysue.tumblr.com/post/37481312454/listening-to-kieron-gillens-podcast-i-learned

Save that I “oversleep” (to 5:30am) a lot lately.

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you go from story idea to finished script? I ask partly cause I write short stories, and that's often taking an idea and running with it and then editing it down later, but it seems like that would be harder to do with a script (writing straight into script form for later editing, that is).

I’ve been thinking about this ask for a while. I even talked to C about it at length when walking in Paris recently. It’s a big one, and probably deserves an essay. Let’s see how this turns out.

In short, it’s complicated. You’re right that there’s a fundamental difference there between comics and prose.

(Most of that is based on writing a comic script is not designed to be a work of art in and of itself. Prose is finished prose. A Script is a guideline. It’s the difference between a blueprint and a building.)

Now, it’s possible you could work like prose, especially prose without a specified work-count. You just churn out panels until you’re done. You’ll probably write without specific panel numbers so you could do some editing of moment, and it’ll only work if you were working in something akin to a graphic novel.

I also think it’s most likely to turn out pretty shit. Generally speaking, writing comics is writing to a form and writing to space.

That “generally speaking” is important. What comics generally is and what it could be are very different things. Always be aware of your assumptions - when people say “Fave comic book movie” when they mean “fave superhero movie” is fairly common one.

In most cases, there’s two specific forms you’re writing to.

One is the page. One is the length of the whole story.

The page is a fundamental narrative unit in almost all print comics. That page turn is a “thing” that will always impact your work. When writing comics, most writers write to the page - what Ellis describes as the Page-as-Stanza approach. This isn’t the only unit - go look at the Hernandez Brothers - but it’s always a pressure. “How will these images look on this single unit of paper” is fundamentally what comics are about. Working out how much information can fit in a page and still have the effect you’re looking for.

This varies in many ways, not least with the artist you’re writing for. Some can be reverse engineered from artist’s previous work. Some can’t - artists surprise you all the time.

The length of the whole story is the other element - in many forms of comics, this is set. I primarily write 20 page American comics, which is an economic construct. I often try and break it in various ways, but that’s me - most people don’t. There’s other forms - the five page future shock for 2000AD, for example. Generally speaking, working in a commercial venue, this is set, and will only bend under extremely rare situations. Even as a pure underground indie writer, there can be an agreement of how long the story will be before starting writing it.

(Not least that you know if you make it too long, the artist will never finish drawing it. The chance of an artist not completing a real b&w indie work increases exponentially for every page you add. I’m only being semi-hyperbolic with that “exponentially”)

That means a story - or a component chapter in a larger story - basically consists of 20 larger narrative units which are subdivided into smaller narrative units.

(My intro to writing comics was Ellis’ 2000-era essays on the topic. He insists you read Dickens to understand serial chapter-based writing. He’s not wrong. That we think of 19th century novels as novels when many were published in serial is a very good analogy to thinking about comics. I think of most of my work as serial novels.)

Notice I say “Narrative units.” I go through periods where I count the number of panel transitions in a comic, when trying to work out how various effects are made.

Okay - that’s a bunch of theory, which I lay out, as it’s the fundamentals of thinking about this shit. As you may note, I lean analytic. Let’s move onto practice.

Basically, reading between the lines, your fear is that the hard limits of mainstream comic storytelling would lead to dead, lifeless work. If you have to plan a story so tightly to make sure it fits into the above form, the actual process is just typing,

I understand that fear, and various writers take different approaches around it. Frankly, the “just typing” approach works for some writers. As I said above, a script isn’t like a story - a script is a blueprint. Maybe it’s okay to be cold. You can do all the creative work in the synopsis, and then “translate” it into comics.

Personally, I’m with you. That sounds really boring. The question becomes how to create improvisational and exploratory energies inside this larger structure.

First step is normally a synopsis, which depending on your instincts can be extremely detailed (akin to a short story) or hyper rough. I lean hyper-rough, for reasons you’ll see shortly. This is where you run with the idea, and explore what would happen.

(I suspect for a short story writer, the “synopsis that may even read like a short story” wouldn’t be a bad way in. You write the story, and then work out how to adapt it to comics.)

You then proceed to take the synopsis and break it into narrative units. How much space does this scene need? I normally go through and write a number by each of the scenes, which is my estimate of how many pages it’ll take.

You then add up the numbers, see how many pages the story is. If all is well in the world, you’ve hit 20. More likely, the number is 28 and you have a little swear for a while, then grab a cup of tea, and then work out how you can cram all this crap in.

(This is where the first part of the improvisational creativity comes in. Comics are a visual medium. As such, you’re trying to work out how you can compress visual information, and work out what’s important. What do you really need in here? If there’s just too much, can you edit it in a way which moves scenes to a future episode? This is why you read widely in comics to be aware of every single short-cut and trick you can, as you’re going to rip them all off as and when you need. Generally speaking, my books are at their most experimental-looking when I’m panicking trying to find something that works. I exaggerate, but only slightly.)

After all that, I’ve got a scene list, with an amount of space in the story assigned to them.

I then write the scenes. Frankly, being me, I write them in almost any order. Brubaker tells me he always writes from beginning to end. I jump around, according to my whims. I see the whole story in my head at once, so it’s almost like painting by numbers on the aforementioned issue plan.

So it sounds like I’m just typing, right, as I’m filling this shit in? Well, yes and no. Sometimes when I’m writing the outline, I’ve hammered out a bunch of dialogue or visual data, and it’s a question of editing that to space (i.e. working out whether the dialogue can work in the space, whether important dialogue can be “acted” correctly by a character in the panel count, etc). Which is a fun creative job in its own way, but also very much the editor.

But remember me saying the outline can be really rough? I mean it’s really rough. It can be…

FIGHT SCENE, CHARACTER X IS SAVED BY SACRIFICE OF CHARACTER Y. (4)

I know more about the beats than that, but often have no idea how the fight is going to go down, what are the hooks, the exact nature of the sacrifice, etc. I know the purpose of the scene, but not always beat for beat. I leave space in the hyper-tight planning to write and have fun.

(And then, due to me writing bits of the issue at once, going and editing things later or earlier to it all lines up. A good idea earlier needs to change later things… but with the structure in place, it all holds together.

Occasionally something does come up which entirely breaks the structure, in which case you just have to rewrite and hack things. Equally, your plan may be wrong - you realise you want 5 pages instead of 4 for that fight sequence to sell the spectacle or emotion or whatever, in which case you work out how you can edit another sequence to get back the page space.

Worth stressing, I used an action sequence as an example. This is also true for more verbal drama scenes. CHARACTER X DISCOVERS CHARACTER Y CHEATED ON THEM. CHARACTER X STORMS OFF. can be the outline, and then I get those two characters talking to each other and see what they have to say.

(You may recognise that one - it’s from WicDiv 16. I knew the bit with the bin as a visual element, but the rest I worked out on the page. After the whole thing was done, I saw the element of the pit running through and brought that out throughout. Edit, edit, edit.)

In short, I try to create places where I can play and discover within a specific space and form. The first place is in the synopsis itself. The second place is within the sub-element of the page.

And I’m going to post this without re-reading, as otherwise I’ll be here all day.

EDIT: One more thing - Antony Johnson talks about a Zero Draft. I don’t always do it, but there’s certainly times when my rough synopsis looks a lot like it, especially when I’ve gone deep on the dialogue.

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fraction on Studying

I'd post a link to it, but I don't know where it might be. The following is from Matt Fraction and Kelly Sue DeConnick's newsletter. Besides seeming incredibly kind and cool folk, they're very generous with process thinking and I found the below to be a great way to begin. ---- HEY PROCESS NERDS I talk(ed) a lot about little games, little tricks, little exercises I did, and do. Finger warmups, fundamentals, notebook doodles for writers and things. Back when DC Comics (is that a... is that redundant? Like saying "ATM Machine"?) launched "The New 52" and I was deeply entrenched at Marvel, I studied the New 52 like, as Brian Michael Bendis says, "like the Torah." It felt, I dunno. The Distinguished Competition were dropping trou and making Declarative Comics, i thought, I dunno, maybe, I should pay attention. So study them like the Torah I did. Anyway -- I found, on a stickie hidden behind another stickie hidden behind another stickie, the notes I took on SUPERGIRL #1 by, I think, Michael Green and Mike Johnson, drawn by Mahmud Asrar, inked by Dan Green, colored by Dave McCraig, lettered by John J. HIll. Edited by Wil Moss & Matt Idelson. Here's what I typed, typos and all. It took about as long to write as it took to type. It's not like it's a long and time consuming process: SUPERGIRL #1 1. 3 panels. meteorite hits earth. 2. 3 panels. meteorite halts. 3. 3 panels. supergirl emerges. 4. SPLASH - supergirl stands. 5. 4 panels. Supergirl sees something. 6. 2 panels. robots arrive; she smiles. 7. 2 panels. robots land. try to capture her. 8. 3 panels. she resists. 9. 5 panels. heat vision activates as she realizes she's not on krypton. 10. 2 panels. she zaps a robot, expresses memory loss 11. 3 panels. she's hit, falls down, hits back. 12. 2 panels. her hands turn odd; she's blown up. 13. 2 panesl. she survives. she runs. 14. 4 panels. she stops, super hearing activates and she collapses. 15. 4 panels. she screams, the soundwaves hit her pursuers 16. 3 panels. she's tackled by a robot. 17. 3 panels. she tears off the robot's arm, hits it, shoves it. 18. 3 panels. tears the helmet off; yells at man inside; other robot holds gun to head. 19. 4 panels. as she holds the first pilot hostage, the second bot is knocked away. 20. SPLASH. reveal it was superman that knocked away the other robot. 12 ad pages, 7 in-house, 9 if you count CN ads, 58 panels total • Now do that 51 more times. Now do it to Richard McGuire's HERE. Now do it to a Mat Brinkman comic. Now do it to seven other things. You'll feel like you cracked open some kind of goddamn genome. If there's a takeaway, without making this any longer than it already is, it'd be study everything. Had I not done this (kind of insane) exercise, I can say definitively, there'd have been no HAWKEYE. I can draw a straight line from DC in Sept 2011 to me a year l

0 notes

Text

Generational Dissonance: communication breakdown

I’ve recently noticed a phenomenon when an old head responds to a question the kids deem the response too harsh or discouraging. Sometimes the kids are right. But youth, be emboldened! Will this rebuke be your epitaph or your rallying call? I honestly believe that this harshness can be a powerful encouragement and in many cases an acknowledgement of potential and intelligence. As someone who sits at the crossroads of generations (generation X!) I’m gonna try and clear things up and give some examples when old heads trounced me.

youtube

…but first a distinction. I’m not talking about adults (like Funkmaster Flex) who are intimidated by generational progression who are handing out unsolicited rebukes of winning young people, but actual adult masters of craft who, when sought out for their opinion, say things that are cryptic or down right severe (like Denzel Washington or Miyazaki Hayao). The latter, I’d argue, are your future selves; they are people who, despite the odds and resistance carved out their place in history and are beckoning you down a rode that looks rough, but is the road to success nevertheless.

When I was a pup, I can distinctly remember at least four times when I sought out the abbot’s wisdom and was summarily trounced from the Shaolin temple with no explanation.

The first occurred on my second year at Pratt institute. I’d survived drugs, orgies, Final Fantasy VII AND Final Fantasy Tactics freshmen year, and would now take my first illustration courses. One of my first teachers was a guy by the name of Chang Park. The first thing this guy said to his students was, “maybe one of you will be a professional illustrator.”

These were harsh words.

But for whatever reason, I did not take this as an excuse to give up. I wasn’t discouraged. I thought to myself, “damn, what are all these other fools gonna end up doing?”

Shortly after I met one of the most influential professors of my time at Pratt, Charles Goslin. Growing up, I had always been the kid who drew best in his class. I had very little training though. I’d learned from studying games, anime, the occasional comics, and the books that my mother or grandmother would get me every once in a while. One of my first crits, I was sure I’d delivered some of my best dynamic figure drawing. Goslin responded with, “Who is this masked marvel? Have you even looked at the model”

I was hurt. But next time I looked at the model. …and I didn’t give up my dynamism or even the influences of pop culture on my work. I just dug deeper.

And this isn’t boot strap talk. I don’t believe these old heads were culling the herd, I believe that the professors wanted each and every one of us to succeed, but for those who could not, it was a merciful opportunity to turn away from a path that could be very difficult.

Senior year, I had a professor who was somewhat of a legend at Pratt Institute, David Passalacqua. He was a gregarious guy, full of profane stories and anecdotes that were often overtly racist or sexist. But I grew to love him. Dead ass, our teachers are problematic. Anyway, for senior year I wanted to try my hand at script illustration and storyboarding.

He scoffed at me, “It’s hard work! storyboard artists do hundreds of drawings!”

“Well if I can do it, You’ll pronounce Ryoichi’s name properly?” (Ryoichi was a classmate and friend of mine. Passalacqua used to call him Roach.)

Passalacqua agreed to the wager.

youtube

The next week, I presented over 200 drawings. I filled the walls of the room. However, Passalacqua never quite got Ryoichi’s name right.

…Ok, last one…er two. Real quick, the first or second time I went to a comic convention was MOCA fest here in NY. I mostly went because Paul Pope was there. I ACTUALLY thought this guy would recognize me as a fellow artist. I gave him a Gratnin mini. I was actually not there yet. At the time, I thought he was dismissive, but looking back, now that I’m closer to where he was then then where I was then, I see things differently. There’s knowledge about the path that can’t be imparted through words but only through chambers.

youtube

Later that day, or was it at a big apple con that year, I think someone introduced me to Evan Dorkin, I forget who. Evan Dorkin was also a bit ridiculous. He offered me a “Get Out of Comics Free” card. I held the card in my hand and laughed but I had only a shallow notion of the poetry of that card. It took me nearly ten years to fully understand. Now I wish I could find it. …maybe I’d use it.

…but anyway, never give up. These old heads are you! They were once you and they’ve worked hard to be in a place where you will seek out their knowledge, but they are, for better or worse, shaped by that path. You may not fully understand their words until you get to where they are. Life is the anvil, their words are the hammer, feel me?

Also, they could just be plain grumpy pusses. Real rap.

-1

youtube

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 tips for comics artists by Moebius

18 tips for comics artists by Moebius

translated this Spanish Moebius list of advice for artists. I thought would be cool to post. (Thanks Xurxo)

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/1996/08/18/sem-moebius.html

1. when you draw you must clean yourself of deep feelings (hate, happiness, ambition, etc)

2 it’s important to educate the hand, attain obedience, to full fill ideas. but careful with perfection, to much, as well as too much speed, as well as their opposites are dangerous. to much looseness, instant drawings,aside from mistakes, there’s no will of the spirit, only the bodies.

3. perspective is of sum importance, it;s a law of manipulation in the good sense, to hypnotise the reader. it;s good to work in real spaces, more that with photos, to exercise our reading of perspective.

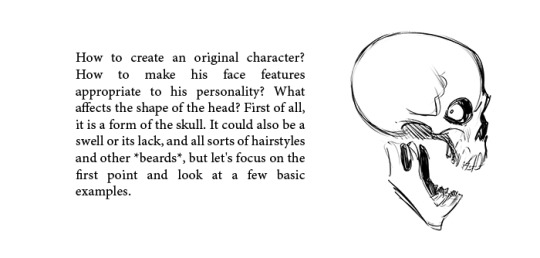

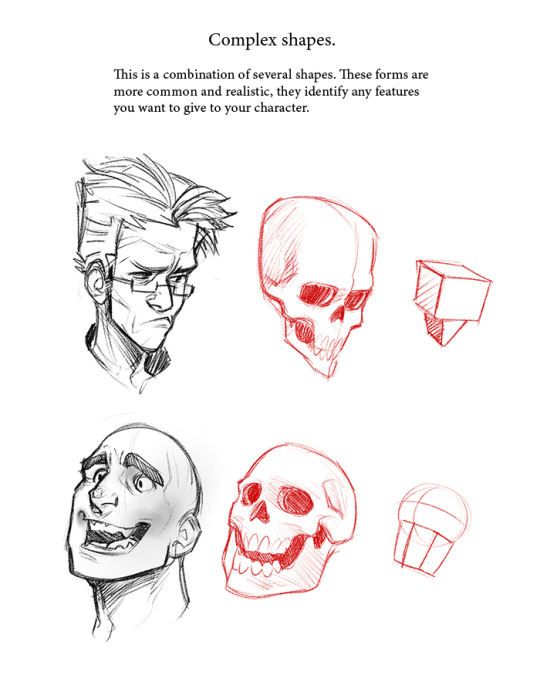

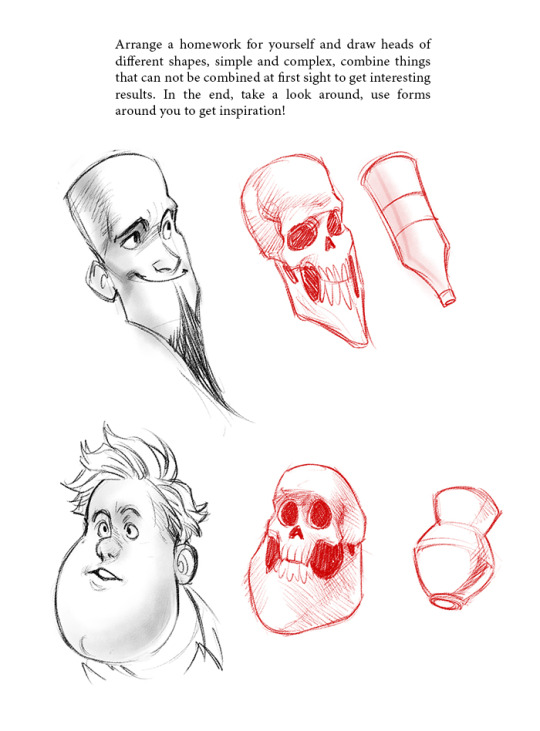

4.another thing to learn with affection is the study of the human body, the positions, the types, the expressions, the arquitecture of bodies, the difference between people. the drawing is very different when it come to a male or a female, because in the male you can change a little the lines, it supports to have some impressions. but with the female precision must be perfect, if not she may turn ugly or upset. then no one buys our book! so for the reader believes the story, the characters must have life and personality of their own, gestures that come from character, from their diseases; the body transforms with life and there’s a message in the structure, in the distribution of fat, in every muscle, in every fold of the face and body. it;s a study of life.

5. when you make a story you can start with out knowing everything, but making notes (in the actual story) about the particular world of that story. that way the reader recognizes and becomes interested. when a character dies in a story, and that character has no story drawn in his face in his body, in his dress, the reader does not care, there’s no emotion. and then the editors say:“your story is worthless, there’s only one dead guys and I need 2) or 30 dead guys for it to work” but that is not true, if the dead guy, or wounded guy or sick guys or whomever is in trouble has a real personality that comes from study, from the artists capacity for observation, emotion will emerge (empathy). In the study you develop an attention for others, a compassion, and a love for humanity.

it’s very important for the development of an artist, if he wants to be a mirror, it must contain inside it;s consciousness the whole world, a mirror that sees everything.

6. jodorwosky says I don’t like drawing dead horses. it;s very difficult. it’s very difficult to draw a body that sleeps, that’s abandoned, because in comics you’re always studying action. it;s easier to draw people fighting thats way Americans always draw superheroes. it;s more difficult to draw people talking, because there are a series of movements, very small, but that have a significance, and that accounts for more, because it need love, attention to the other, to the little things that speak of personality, of life. the superheores have no personality, all of them have the same gestures and movements (pantomimes ferocity, running and fighting)

7. equally important is the clothing of the characters, the state they;re in, the materials, the textures are a vision of their experiences, of their lives, their situation in the adventure, that can say a lot with out words. In a drew there’s a million folds, you must chose 2 or 3, but the good ones.

8. the style, the stylistically continuity of an artist is symbolical, it can be read like the tarot. I chose as a joke the name Moebius, when I was 22, but in truth there’s a meaning to that. if you bring a t shirt with Don Quixote, that speaks to me of who you are. in my case, I give importance to a drawing of relative simplicity, that way subtle indications can be made.

9. when an artist, a drawing artist goes out on the street, he does not see the same things other people see. what he sees is documentation about a way of life, about people.

10. another important element is composition. the composition on our stories must be studied, because a page, or a painting, is a face that looks towards (faces) the reader and that speaks to him. it’s not a succession of panels with out meaning. there’s panels that are full and some that are empty, others that have a vertical dynamic or a horizontal one, and on that there is intention. the vertical excites (cheers), the horizontal calms, an oblique to the right , for us westerners, represents the action heads towards the future, and oblique to the left directs action toward the past. points (points of attention) represent a dispersion of energy. something places in the middle focalises energy and attention, it concentrates.

these are basic symbols for reading, that exercise a fascination, a hypnosis. you must have a consciousness about rhythm, set traps for the reader to fall on to, and if he falls, and gets lost and may move inside them with pleasure because there’s life. you must study the great painters, the ones that speak with their paintings, of any school or period, that does not matter, and they must be seen with that preoccupation for physical composition, but also emotional. in what way the combination of lines on that artist touches us directly in the heart.

11. narration must harmonize with the drawing. there must be a visual rhythm from the placement of words, plot must correctly maneuver cadence, to compress or expand time. must weary of the election and direction of characters. use them as a film director and study all different takes.

12. careful with the devastating influence of north american comics in mexico, they only study a little anatomy, dynamic composition, the monsters, the fights, the screaming and teeth (grin). I like them as well, but there are many other possibilities that must be explored.

13. there’s a connection between music and drawing. but that depends also on the personality and the moment. for perhaps 10 years I’ve been working in silence, and for me the music is rhythm of the lines (the music he listens to).

to draw is sometimes to hunt for findings, an exact (fair, just) line is an orgasm!

14. color is a language that the artist (drawing artist) uses to manipulate the readers attention and to create beauty. there’s objective and subjective color, the emotional states of the character influence the coloring and lighting can change from one panel to the next, depending on the space represented and the time of the day. the language of color must be studied with attention.

15. especially at the beginning of a career, one should work on short stories but of a very high quality. there’s a better chance to finish them successfully and place them on a book or with editors.

16. there are times when we are headed to failure knowingly, we choose a theme, an existence, a technique that does not suit (convene) us. you must not complain afterwards.

17. when new pages are sent to editors and see rejection, we should ask for the reasons. we must study the reasons for failure and learn. it’s not about struggle with our limitations or with public or the publishers. it’s more about treating it like in aikido; the strength (power) of the attack is used to defeat him with the same effort.

18. now it is possible to find reader in any part of the planet. we must have this present. to begin with, drawing is a way of personal communication, but this does not imply that the artist must envelop himself in a bubble; it’ communication with the beings near us, with oneself, but also with unknown people. Drawing is a medium to communicate with the great family we have not met, the public, the world.

august 18th 1996 compiled by Perez Ruiz

510 notes

·

View notes