Text

Before we continue, is this a personal moral failing or a mental illness? I need to know whether I should treat you like an evil monster or a helpless child when I unperson you.

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

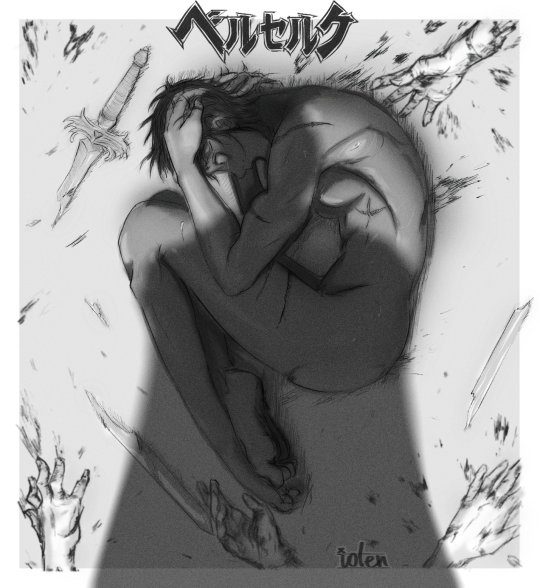

young Casca and Judeau

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dream… It’s something you do for yourself, not for others.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Griffith's Relationships (3)

The White Hawk. The White Phoenix. The King of Falconia. The Savior. Femto. The Blessed King of Longing. Once, the greatest mortal to ever wield a sword. The bane of the Black Swordsman. The most beautiful man alive. Him with a stature nothing short of pure magnificence. You know him. You love to hate him. I’m talking about one of the greatest characters not just in manga, but in all of fiction: Griffith.

Griffith is one of many examples of how masterful Kentaro Miura was with a pen, be it pressing against a notebook or a panel. An incredibly written character, as complex as they can come, with some of the most complicated, deep, and tragic relationships I’ve ever seen put to any form of media.

Today, I’ll be discussing what is inarguably a core tenet of Berserk: Griffith’s relationships. With two exceptions, there is no dispute that Griffith’s relationships are not the singular most important part of the media he resides in, there is no debate over whether or not they are still crucial parts of understanding both Guts’ disposition, and the world of Berserk itself. Griffith’s different approaches to interacting with those in his vicinity warps the very world itself, and his whims shape the very nature of the conflicts the protagonist engages in.

Here, we will be discussing Griffith’s most important relationships through Berserk, how they shaped him, and what they explain about who he is and how he got to where he is now.

Part 1: The Boy, and The Hawks

Part 2: The Governor.

Part 3: The King.

Part 4: Charlotte.

Part 5: The Wings of the Hawk (1)

Part 6: The Wings of the Hawk (2)

______________________________________________________________

Part 3: The King

The man who lords over Midland is many things, but he is nothing if not faithful in Griffith’s ability to succeed. In the war council deciding what was to be done about Doldrey, what was once Midland’s greatest bastion against Chuder, and now was the home of the Holy Purple Rhino Knights and the base of operations of their assault on the very nation which originally owned the fort, Griffith alone is completely confident in the fact that the fort can be captured. Not only so, but he remains adamant through the meeting that he and his forces alone could best General Boscogn and his men. There is but one single voice to support The Band of the Hawk, a noble named Sir Laban. Laban puts their situation quite simply: a small force like the Hawks being bested in combat should do no damage to the entirety of Midland’s otherwise massive force of arms. Besides, the Hawks have shown prodigious ability, being undefeated until this point. There is no further harm in allowing them to attempt, even with their paltry 5,000 men, against the occupying force of 30,000 strong.

The king looks on at this circus amongst his advisors, lower lords, and generals, and has but a single statement to utter.

“Sir Griffith.

Was that sincere?”

And upon Griffith’s affirmation, he orders the Hawks to take Doldrey.

And upon Griffith’s orders, they do.

There is a celebration held when the Hawks return home. An armistice agreement is sent, signed from Chuder, and the war is over. The king is gracious, generous, putting Griffith as the White Phoenix General, and promoting all of the Hawk, now White Phoenix, division leaders to peerage. But this same night, tragedy strikes.

Griffith falls ill, nearly dying. Then, later on, as Griffith recovers, Charlotte is kidnapped, and returned, and the Queen dies, along with countless other nobles, in a fire that collapses a building. So much bloodshed, between moments of endless revelry. The King is stricken with grief and tragedy. An endless river of crimson flows, despite Midland finally being able to erect a dam to stop it. But as the King says later, “The monster named War is always seeking new blood, starting to brew itself anew”. And the King is still at war. Not with Chuder, not even the war with Kushan. But he is at war with that which soars on beams of light, whose wings flap with the strength of hurricanes but the delicateness of a gentle night’s breeze. He is at war with the very concept of Griffith. He is at war with the very sky that supports the White Hawk. But he does not yet know it.

Griffith, too, is stricken with tragedy. But it is not crimson that flows from Griffith, but azure.The tragedy of loss, loss beyond any tragedy he had experienced to this point. Every difficulty Griffith has encountered has since only served to strengthen his resolve, no matter how much it may be to his detriment. But this? This breaks him. And “this” is the abandonment of the Hawks, of himself, by Guts. Guts defeated Griffith in a single stroke in combat, earning back his life and his freedom. And Griffith, a man who has only known control and power as his substitutes for affection, is broken. And so, he goes out, in search of some meager amount of solace that something in the world can provide. And ultimately, he reaches the window of a certain someone, quite important to Midland, and even more so to the King himself. He reaches the window to the chambers of Princess Charlotte, daughter of the King of Midland.

But Griffith finds no solace here. Even inside the Princess, his thoughts, his eyes, wander to Guts. It haunts his vision, in every stroke, with every blink, every shudder, only makes him wish he had won that fight. Charlotte’s body is not a shrine to Griffith, nor even just another body to use. It is a tool to vent his frustration, to pour into the dissolving, unraveling of his very psyche. And this meltdown is witnessed by a rogue maid, peering through the keyhole in Charlotte’s doors to her chamber. And he is arrested as he flees the very next morning, sword not in hand.

And so, the two men meet. Face to face, but not as equals. Griffith, bound and chained, strung up on a board. The King, staring up at him as he hangs from his wrists attached to a rope on the ceiling, whip in hand. And the king confirms, as he tears Griffith’s skin apart, crack by crack, slit by slit, with each sewing of the whip, that Griffith’s dream was a mere moment away. That, despite his disgusting blood, if he had merely retained patience, he could have, perhaps, attained his dream. But instead, Griffith merely proved the rumors around the court correct. He was not a Hawk, but a vulture, waiting to pick at the scraps of opportunity left behind by the war. The King rants to Griffith, starting about the weight he holds on his shoulders, but slowly, steadily and horrifically veering towards his daughter. Towards her ignorance, at first, and then, her naivete. Then, her innocence. Then, finally, her impurity. How Griffith soiled her. How Griffith plucked from him the one flower he so desperately wanted. And that it was soiled, now that she had given herself up to him.

And something, in that moment, clicks for Griffith. Despite his wounds, despite the blood loss, his mind connects threads that weave together the full picture:

“That you…

Rather…

To have been with Princess Charlotte…

Would have had her yourself?

Don’t you want her to have you?”

And this breaks the King. To be exposed, even in the lowest levels of Midland’s deepest, darkest dungeon. Here, even in the pits of his shame, does a spotlight flash on him. In the darkness, beacons point directly at him, blinding him, searing him in his squalor, all aimed by the Hawk’s burning truth. His protection of Charlotte is, at least not in its entirety, not based in his love for her as his daughter. At least partially, if not more… he is motivated by his desire. He desires her, his own seed. And more, he knows this, and does nothing. He does not push himself because of it, or in spite of it. He merely sequesters her away from the world, putting it on her shyness, and tried not to be a better king, but to reach a place where he can enjoy her. His only motivation is his daughter, but it is not love; not the kind of love that makes one a good king, or a good man. The kind of love, of longing, of lusting that tears a man’s soul apart. And this has led the king to become a hollowed version of himself after the passing of his first wife.

And Griffith sees this. And he sees right through the King.

And the King does not enjoy this. He tears into Griffith, before leaving him to rot with the torturer. And then, he does exactly as Griffith claimed. He goes, observing his daughter in her doctor-enabled sleep. He obsesses over her, over her body. Over Griffith’s claim over her body. He lusts over her, over how she has grown so much into the shape of her mother before her. He obsesses over how Griffith lay claim to the very features that once belonged to his wife. And then, in her sleep, the King begins to molest her. And when she attempts to fight him off, eventually succeeding, it is Griffith’s name that Charlotte calls out. Even in the depths of his defeat, Griffith succeeds in towering over the king with the mere shadow of his presence.

They needed each other, from the start. The King needed someone able to truly fight, who could wield every ounce of conviction in their soul, and the souls around them, in order to turn around what had been raging for a century. And Griffith? Griffith needed a way into his dream. A way to have his kingdom. But through this, they both made terrible decisions. And ultimately, the king’s own lust betrayed him. If the King had even been able to come to terms with how he truly felt about his daughter, much less deal with it properly, things would not have turned out the way they had. Instead, ironically enough, the King’s wish that Griffith suffer in that following year, and his overprotective, obsessive lust for his daughter, turned Griffith into the very White Phoenix that he so desperately wished to eradicate the possibility of.

The King, in a very tangible way, caused the Eclipse. Caused his own downfall. And Griffith, cemented in a way by the life experience he had earlier on with the Governor, saw the King and Charlotte both as nothing but a stepping stone on the journey to his dream. And when he lost that? When he knew, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that there was no possibility for the King to be able to assist him any further in his pursuit of his dream? He cast him aside like a stone on the road, and nothing more. And he spoke the truth to the King. And ironically enough, this very betrayal between the both of them is what awarded him with the blood-soaked version of the dream he aspired to, but blood-soaked or not, he treats it as though it were his dream all the same.

Ultimately, I take Griffith’s relationship with the king as one of simple mutual benefit. And when the mutual benefit is lost, it reveals the two’s truer natures- The King as a coward, and a disgusting pig, and Griffith, as an almost supernatural studier of all around him. Griffith is corrupted by corruption, is truly turned evil by evil. Guts’ disappearance may have broken him, but The King’s betrayal is what put him in a state enough to ever perform the things he eventually does. But this is far from shocking or surprising. Broken men breed broken men, turn them into broken soldiers, and are caught off guard when they break. In this case, the only issue was that his breaking broke everything.

If the King did not long for his daughter with such powerful carnality, if he accepted what he assumed was to occur- as he says to Griffith, his eventual succession to the throne through Charlotte- then all of this tragedy could have been avoided. But the King destroyed Griffith, and his sins ultimately destroyed him. In this way, the two are almost parallels- both traitors to themselves. The only difference between the two of them is we see how it started for them both, and how they both suffer from it- we just have not seen how it ends for one.

#griffith#berserk#berserk meta#they are parallels in how they are burdened by the fact that they hold the lives of countless people on their shoulders therefore have to#act in ways benefitting the masses rather than the few ones they care for#but they are also parallels in how they long after people they dont even acknowledge wanting until these people are already out of their#reach. griffith could have aknowledged he cared for guts and worked up the courage to make it his strength or let it die organically but#instead he denies it ever existing... until he cant deny it anymore. until guts leaves. until guts chooses someone else. until he ruins#everything over it. he understands the king because he feels the same way. its the reason he was thrown in that predicament in the first#place. those words: would you rather have her? wouldnt you rather she had you? he is saying because he knows. he KNOWS. he can take#everything by force. as he did. as the king tries to do. but he wants to be wanted. to be chosen. for the person he longs for to come to him#willingly. it never happens.#i think it is telling of griffith's fucked up sense of self to equate his desire of having guts by his side with the kings lust for his own#daughter but hey! he IS dirty AND cruel. everything that he wants must be so too right?#yk i always rant in the tags. im pretty sure there is a post i have rb that expands on these tags beautifully. i was reminded of it#beautiful post as always!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

all of my haters want to see me bound bled and crucified for my misdeeds. my paramours also want to see me bound bled and crucified for my misdeeds but they get hard when they think about it so it;s fine

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

ohhh fuck off. someone learned my summoning ritual again. ill be right back

#berserk#griffith#femto being fucking summoned by guts every two weeks just to get yelled at then leave#<<😭#its called divorce babes😔

120K notes

·

View notes

Text

guards! take his gender away and beat them to an inch of their life

#berserk#griffith#unfortunately for everyone they have fermented in that dungeon and spawned a New; Eviler gender#<<true

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Griffith's Relationships (2)

The White Hawk. The White Phoenix. The King of Falconia. The Savior. Femto. The Blessed King of Longing. Once, the greatest mortal to ever wield a sword. The bane of the Black Swordsman. The most beautiful man alive. Him with a stature nothing short of pure magnificence. You know him. You love to hate him. I’m talking about one of the greatest characters not just in manga, but in all of fiction: Griffith.

Griffith is one of many examples of how masterful Kentaro Miura was with a pen, be it pressing against a notebook or a panel. An incredibly written character, as complex as they can come, with some of the most complicated, deep, and tragic relationships I’ve ever seen put to any form of media.

Today, I’ll be discussing what is inarguably a core tenet of Berserk: Griffith’s relationships. With two exceptions, there is no dispute that Griffith’s relationships are not the singular most important part of the media he resides in, there is no debate over whether or not they are still crucial parts of understanding both Guts’ disposition, and the world of Berserk itself. Griffith’s different approaches to interacting with those in his vicinity warps the very world itself, and his whims shape the very nature of the conflicts the protagonist engages in.

Here, we will be discussing Griffith’s most important relationships through Berserk, how they shaped him, and what they explain about who he is and how he got to where he is now.

Part 1: The Boy, and The Hawks

Part 2: The Governor.

Part 3: The King.

Part 4: Charlotte.

Part 5: The Wings of the Hawk (1)

Part 6: The Wings of the Hawk (2)

______________________________________________________________

Part 2: The Governor

Griffith was a young boy, molested by an old man to increase the odds of a shot at his pipe dream. Later on, Griffith proves he deserves no sympathy. A larger-than-life figure, a literal living legend, born from a mountain of bones and bloodshed he could have prevented. But here, in this moment, acting out of pure desperation to succeed after a watershed moment in his time as a leader, Griffith is small. He is weak. He is taking on an impossible task, chiseling a quarry into a sculpture with nothing but a rock in his hand. To go from a peasant in a run-down town, to a noble, much less a king, would get him laughed out of any of Midland’s few places that would accept him, and perhaps fare much worse fates when presented with any of that royal blood itself. He needs any resources he can scrounge up, even more so after the devastation that the death of a young boy under his care wrought on his psyche. And so, in this moment, Griffith chooses to put his dream, and his people, over himself, allowing the most debasing act humanely possible to be performed with his body, giving up any notions of autonomy through the “allowed” desecration of his physicality, all for the sake of attempting to gain his self-efficacy back through the easing of the also grueling task that still lays before him.

This obliterated Griffith’s self-image, the very notion of himself that he carried in his own mind. He breaks down into tears the dawn of the very next day, Casca alone there to witness. While attempting to talk very seriously about the logistics of the coming struggles he must deal with, putting on the face that it is through these reasons alone he performs the acts he does, he also grips his arms, tearing so hard he rends his own flesh, blood running down into the water he was cleaning himself in below. His real mental state slips through, if only for a moment. This Griffith is not as emotionally or psychologically refined as who he will become. He looks at Casca, spotting her as she attempts to flee the scene before his breakdown begins. He asks her, quite plainly: “Am I dirty?” And, although you cannot blame Casca for how she responds, considering she is even younger than him, she does not say no. She does not respond to the question at all, letting it linger, before asking him a question of her own.

He did it for troops, he says. He did it for money, power, means through which to acquire all he desires. But he primarily did it, of course, as a shortcut. Whatever resources he gains through other means, means less resources have to be gained at the expense of his troops. Whatever gold, whatever prowess, whatever the currency, he reasons that it has a value not just worth itself, but one which includes the cost of the lives he would have to stake in order to get it through warfare. This is how Griffith, in his own way, warped by the path he has been on and the decisions that have been both made by and thrust upon him, shows his affection. Shows how valuable his troops, his people, how valuable each individual life is to him.

To the governor, Griffith was easily worth whatever measly trinkets he had to throw his way. In fact, Griffith was quite literally “worth the value of his weight in gold, an intoxicating phantom.” To this day, all this time later, that singular night of “revelry” has dominated his mind. Obsessively. Every boy now in his… care… bears resemblance. Every one of them carries his face. Every one of them wears his hair. Every spare, waking moment has been filled with nothing but the thought of how he might, one day, be lucky enough to cage the White Hawk. And one day, an opportunity arises. The Hawks, the greatest force in Midland’s army, have been sent to capture the very castle he resides in. And this lingers in his mind as the battle draws out, the chance to once again have Griffith in his palms nearly as titillating as the memory itself.

So much so, in fact, that the Governor throws the battle away. He sets outlandish rewards for an even more outlandish request: take the Hawk, and clip his wings, and carry him to me, with nary a scratch otherwise. And this costs them the battle, and may well lose them the war. And this leads to yet another face-to-face with the Hawk himself.

And those eyes.

Griffith puts on a very cold, calculating facade through the entirety of Berserk, but it is very clear that this is exactly that- a facade. When he is in a particularly expressive mood, there is one part of him that betrays his true feelings: his eyes. Eyes show the soul, or so they say, and Griffith embodies this idea to his very core. Griffith’s eyes are as much windows to his true feelings as they are windows to hell. They are known for almost literally freezing characters in place, with the pure intensity they emanate out into the world, and specifically at whoever is looking. They are his truest way to show how he really feels about any particular event, and in the case of the Governor, they hold such raw malice that it instantly makes him sweat. It also betrays that despite what he claims immediately after his eyes betray him, the governor has, indeed, occupied quite a space in Griffith’s mind since the event transpired.

Those eyes Griffith carries, which wear his passion, his fiery disposition, however he may feel and to whoever it may be directed right on his face. Those eyes, here, so full of seething disgust and rampant hatred, that even he cannot pretend so well as to feign ignorance to his feelings. The Governor notices the waves of turbulence, seeing those eyes, and asks Griffith outright if he has any hatred for him. Griffith rejects the idea, recovering from his stupor at the mere sight of the man who once violated him, and denies him. No, he says, “I do not resent you.” But once again, Griffith betrays himself.

He goes on another long tangent about the logistics behind his decision-making, and then slips again.

“However, it would be quite beyond reason to say that I’ve yearned for you.

I simply have no emotional interest in you at all. Resentment, endearment… nothing.

I just took the liberty of using you when the opportunity appeared.

You were like a stone lying by the side of the path I walk.

That… and nothing more.”

And then, when all is said and done?

Griffith stabs him in the face, citing that him being alive to spread unsightly rumors would be a risk to his dream.

Once more, Griffith engages with his emotions in an emotionally self-destructive way, and once again, his habits are reinforced. There is no blowback from doing this to the governor. There is no solace to be found in it, sure, as the effects he left on Griffith linger into perpetuity, but there is no harm in his action. Except for to himself. It allows him to continue engaging in these behaviors, to continue to shut himself off emotionally and act as though rules, and logic, and objectivity are what gear his thinking, even though he is, at his heart, an emotional man, controlled by emotional experiences. Perhaps, if not for the governor’s hanging influence over his life, he would not make the decisions he does later. Perhaps, if not for the governor’s hanging influence, he would not act the way he does. As I will discuss later, Sexuality, Affection, and Romance become both a part of Griffith's toolbelt and a looming shadow that darkens his thoughts.

Because the governor’s touch did not just poison Griffith’s body, but his mind, his heart, and the very soul of his will.

#berserk#griffith#griffith definitely took the WRONG lesson from this encounter#what it did to my GOAT is... incredibly unfortunate.#and what comfort#what solace could Casca give#as a child younger than him#less experienced#seeing her god reduced to a man?#<<beautiful tags#berserk meta

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Griffith's Relationships

The White Hawk. The White Phoenix. The King of Falconia. The Savior. Femto. The Blessed King of Longing. Once, the greatest mortal to ever wield a sword. The bane of the Black Swordsman. The most beautiful man alive. Him with a stature nothing short of pure magnificence. You know him. You love to hate him. I’m talking about one of the greatest characters not just in manga, but in all of fiction: Griffith.

Griffith is one of many examples of how masterful Kentaro Miura was with a pen, be it pressing against a notebook or a panel. An incredibly written character, as complex as they can come, with some of the most complicated, deep, and tragic relationships I’ve ever seen put to any form of media.

Here, I’ll be discussing what is inarguably a core tenet of Berserk: Griffith’s relationships. With two exceptions, there is no dispute that Griffith’s relationships are the singular most important part of the media he resides in, there is no debate over whether or not they are still crucial parts of understanding both Guts’ disposition, and the world of Berserk. Griffith’s different approaches to interacting with those in his vicinity warps the very world itself, and his whims shape the very nature of the conflicts the protagonist engages in.

Here, in 6 parts, we will be dissecting Griffith’s most important relationships through Berserk, how they shaped him, and what they explain about who he is and how he got to where he is now.

Part 1: The Boy, and The Hawks

Part 2: The Noble.

Part 3: The King.

Part 4: Charlotte.

Part 5: The Wings of the Hawk (1)

Part 6: The Wings of the Hawk (2)

______________________________________________________________

Part 1: The Boy, and The Hawks

Throughout the story of Berserk, Griffith goes through many changes, some more drastic than others. But no change is more pivotal than the one caused by a certain young bird who flocked with him and the Hawks when he first started his journey. Before Guts, before Casca, Griffith was no one. He was a commoner, no more than a child, starting his own little group of misfit warriors to become… something. Whatever it was, surely, it must set him on the path to his dream. But to the others, whatever that something was did not matter. It was of no consequence to them whether that mystical something ever came into fruition. All that mattered was that Griffith was the one who was pulling them along with him into the smoke that obscured their immediate war-torn futures.

Among them was a young boy. Younger than Griffith, even. So young, he would even bring his toys onto the battlefield. A young boy who admired him from what he thought was afar, but in actuality could be only a few feet away at times. It was like admiring a star, or, as Griffith puts it, “the hero of some story.” A hero not too unlike the toy knight Griffith found one day in his satchel, no owner left to claim it, as he lay on the ground, blood pooling around him as it soaked through his bare clothes, no armor, merely a tunic and a dream. A dream to serve alongside Griffith. A dream to aid Griffith in achieving his dream, a small dream, a dream to aid another man’s story.

Griffith wondered, as he placed the boy’s toy back on his chest, whether, when he died, he felt comfort from his dream. Or, perhaps, did he die in agony, unable to achieve it? Was death the start of a new dream, or the end of all other ones? Was it even the boy’s dream that he felt as he slipped away? Or was it the dream Griffith imposed upon him? He did not know the answers.

But he knew one thing- that he could no longer idly hope for his dream to be achieved. He knew he could not simply throw enough numbers at the board, have enough fights, gain enough men, and maybe he’d get lucky, and his dream would simply fall into his lap. He would have to take initiative. He would have to work for his dream, would have to devote every waking moment, every sleeping moment, to the pursuit of that dream.

One night, later on, upon returning to the castle, Casca finds Griffith with a man known for… having a particular taste regarding young boys. Later on, she finds him, bathing himself in a nearby river. He begins to quite literally tear into himself, ripping open his arm in a perfect metaphor for how he feels. He claims he has logically reasoned out that what he did was necessary in order to make sure that he gets the funds needed to properly helm a militia the size he will require. But this is only after admitting that he feels that he must be as filthy as those who follow him, because he does not deserve to be clean when his dream is smeared in the blood of thousands who follow his words.

Despite his supposed recovery from this mental break, and despite his claims, the scene of that young boy, dead on the battlefield, with his only belonging encapsulating the lofty ideal to which he held Griffith, broke him. It could have, should have broken any man who would be in the same situation. But it did not just break Griffith. It melted him down, only to reforge him again. That young boy pushed Griffith to do whatever it takes to achieve his dreams, and to accept that casualties will occur. It was a notion Griffith accepted, but not one he fully understood until it was there, laid bare in front of him, forcing him to either confront it, or to give up. And Griffith confronted it. And it warped him. As the story progresses, we see that Griffith is still affected by the death of this young boy, and that his blood still stains crimson all of Griffith’s decisions.

Without this death, perhaps Griffith is content to simply grow the Hawks through skirmishes, through battle, and through battle alone, until another opportunity presents itself. Perhaps Griffith does not sleep with the old man. Perhaps Griffith does not engage in the activities he does later on in the story, assassinating rivals in his chase of his dream of a throne. Perhaps he does not pull Guts as his sole equal in the depravity he lowers himself to for his dream, sending him on an assassination mission where Guts has a realization of equal magnitude to his own. But Griffith does not recover from this spiral. Perhaps, if this child did not die as a result of Griffith’s own actions, perhaps The eclipse never occurs. Perhaps Griffith must work ten times as hard, it takes ten times as long, but perhaps Griffith does not become the false emotional stonewall he acts as. Perhaps he gains a new dream, perhaps he does not, but either way, perhaps he can have that journey with those he loves, he values, to keep him company.

And Griffith loves the Hawks. All of them. Perhaps not to the same degree, but for all of them, Griffith feels this same type of patriarchal, shepherd-esque obligation, with perhaps the exception of Guts, and Guts alone. He takes on the burden of making the hard choices, of putting himself through hell, to attempt to mitigate the harm they can potentially receive as much as possible. He bears the weight of every victory, every loss of every individual, all willingly given for the sake of his dream. He alone bears the cross of being the head of the Hawks, at every step of their journey.

And this makes his decision at the Eclipse all the more powerful. Some may think that Griffith made the decision because he did not actually care about the Hawks, those who would so loyally lay down their lives if he were to so much as ask. But no. The thing that makes Griffith’s decision to follow that through, to sacrifice all of the Hawks for the sake of his dream so sickening, so gut-wrenchingly despicable, is that he does care. He values each and every single life that was lost at the hands of the apostles, and the demons that began to ravage his party at his behest. He has to care. After all, the Behelit requires him to sacrifice whatever he values most in order to give him his chance at his dream.

All this death and mayhem, yet underneath it all, it is the scarlet blood of a single child, barely younger than him, that tinges Griffith’s memory.

#please continue this analysis!! it is beautiful to see written down and organised so eloquently#im curious to see your take om the other topics you mentioned#griffith#berserk#berserk meta

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Casca will never be the same…”

AUTHOR LINK: https://twitter.com/io_T_en

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly though, I think one of the biggest wtfs I have about berserk fandom is this belief that humanity is somehow inherently a good thing (within the context of Berserk). I do realize that’s kind of… the perspective we’re used to taking, and I know I contribute to it because I… have a hard time thinking of ways to say the things I’m trying to say without referencing humanity as a theoretical good. It’s just really heavily ingrained into our language, though it may be worth taking a minute to figure out a way around but…

Nearly every Godhand and apostle that has existed… exists because some human broke them. Their willingness to take up the Sacrifice is a direct result of humans hurting them so much that they were willing to do anything at all to make it stop. And the majority of the worst, most reprehensible characters in berserk are human.

It’s humanity’s desire that created the whole damn system - humanity invented the Idea of Evil, humanity begged for Griffith, even the monster plagued world Griffith created is explicitly defined as the world humanity wished for.

So…. you know.

Not saying everyone should become demons I’m just saying there’s nothing inherently more noble about not doing that. Well, you can say not accepting sacrifices is noble, but its not like people who dont’ accept sacrifices are guaranteed to be great.

Truth be told, I’m not even sure Guts would be so anti-demon if demons hadn’t eaten the Hawks. Like sure he’s anti-human now, but isn’t that largely because monsters killed his friends and are always trying to gnaw him to death?

110 notes

·

View notes

Photo

suddenly i really wanna see griffith break out into a little evil musical number

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Popular Berserk fan-theories:

Warning: Spoilers for up to chapter 338.

The Skull Knight is actually Gaiseric, who was sacrificed by the person who then became the God-Hand ��Void’ as a result.

Void is actually one of the aliens from ‘Mars Attacks!’. The Skull Knight will figure out (purely by accident) that Void is vulnerable against a random, obscure, old song and will play it until Void’s head explodes. Like with the film ‘Mars Attacks!’ (and many of Berserk’s more creative Apostle/demon encounters with Guts) no one will understand what the hell they just saw or why/how any of it happened. The art will be beautiful and gruesome.

Keep reading

#no one will sacrifice ivarella killed me😭 it KILLED ME😭😭#great post#one of the greatest of all time#berserk#berserk crack#guts#griffith#casca#anddddd everyone else ig lol

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Or so I am learning.

#there should be more shitposting in berserk situation methinks#i think ppl take berserk too seriously... one of the characters pants like a dog the other one flaunts his flat ass in every chapter he's in#they have a wild e coyote and roadrunner dynamic#why the FUCK does none of yall have fun with all this??#berserk#griffith#guts

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

(◡‿◡✿)

(ʘ‿ʘ✿) “what you say ‘bout me”

(ʘ‿ʘ)ノ✿ “hold my flower”

1M notes

·

View notes