Text

Eighteenth-century manuscript culture in the wider Gaelic world: The manuscripts of Rev James McLagan (1728-1805) in context

WHEN:Wednesday, June 19, 2019 - 09:15-Wednesday, June 19, 2019 - 16:45

WHERE: Academy House, 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2

TICKETS: Full price €10 Concession (student, retired, unemployed) €8

A one-day conference on eighteenth-century manuscript culture in the wider gaelic World.

The Rev. James McLagan (1728-1805) was a pre-eminent Scottish Gaelic scholar, poet, manuscript-collector, lexicographer as well as a military chaplain. His career with the Black Watch regiment saw him on active military service throughout Ireland, the Isle of Man and in the American War of Independence. Using McLagan and his extensive collection of Gaelic literary material as a point of departure, this event explores issues of eighteenth-century Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic manuscript and literary culture, with a particular focus on fiannaigheacht lays and ‘Ossian’, scholarly networks, oral tradition, historical and political contexts for manuscript creation and collection. This event is part of the ‘Gaelic Literature in Enlightenment Scotland: The McLagan Ossianic material’ research network, funded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh and led by Celtic and Gaelic, University of Glasgow, with the support of the Royal Irish Academy’s Coiste Léann na Gaeilge, Litríocht na Gaeilge agus na gCultúr Ceilteach.

Programme

09:15 Fàilte | Fáilte: Prof. Alan Titley MRIA

09.30 Dr Sìm Innes, University of Glasgow Creating a McLagan online resource: ‘Teanntachd Mhòr na Fèinne’ as case study

10:00 Dr Geraldine Parsons, University of Glasgow ‘Mas Oisean liath mi’: James McLagan’s Ossianic interests in a military context

10:30 Prof. Pádraig Ó Macháin, University College Cork The moral of fianaigheacht

11:00 Tea/coffee

11:30 Prof. Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh, University of Glasgow Muiris Ó Gormáin Manuscripts in Scotland

12:00 Prof. Nigel Leask, University of Glasgow ‘My scepticism is vanishing like the morning mist’: John Leyden and Ossian Tourism, circa 1800

12:30 Dr Peadar Ó Muircheartaigh, Aberystwyth University McLagan and Ossian in the Isle of Man

13:00 Lunch and Library Exhibition

14:00 Dr Síle Ní Mhurchú, University College Cork On the manuscript transmission of some of the lays of Fionn mac Cumhaill

14:30 Dr Anja Gunderloch, University of Edinburgh ‘Laoidh an Deirg’ in the McLagan Collection

15:00 Prof. Ruairí Ó hUiginn, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies ‘Laoidh Chonnlaoich’: text and transmission

15:30 Tea/coffee

16:00 Alasdair MacIlleBhàin Performance of songs from the McLagan manuscripts

17:00 Close

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ulidia VI Fíanaigecht III: joint meeting of the Ulster Cycle and Finn Cycle Conferences

Readers of Ossian Online may be interested to learn of Ulidia VI Fíanaigecht III, a joint meeting of the Ulster Cycle and Finn Cycle Conferences to be held at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig in the Isle of Skye from 13-17 June 2018.

The meeting anticipates that bringing Ulster Cycle and Finn Cycle scholarship together will encourage Celticists to engage more closely with Ossianic scholarship, particularly in relation to the late medieval and early modern sources where the 'dividing line' between the cycles is much less present than in the early material, and in relation to the post-Ossianic material that appears in Irish and Gaelic in response to Ossian. The organisers are particularly interested in comparative papers that might help to explore these areas.

Proposals are due by 31 January 2018, and further details of the Call For Papers can be found at http://www.ulidiafinn2018.scot.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Ossian’s lyricism’: Portuguese women’s translations

The following guest post comes from Gerald Bär of Universidade Aberta, whose publications include many important contributions to Ossian Studies. A fuller treatment of the topic of this post can be found in his article for Translation and Literature, “‘Ossian fürs Frauenzimmer’? Lengefeld, Günderrode, and the Portuguese Translations of ‘Alcipe’ and Adelaide Prata.”

When deciding on the title for my Portuguese translations of Ossian, I had to choose between ‘poemas’ and ‘poesias’. Bearing in mind the remarkable lyrical aspect in the reception and perception of the Ossianic poems, I used the latter word in order to emphasize their emotional and sentimental impact: Poesias de Ossian: Antologia das traduções em português (Lisbon, Universidade Católica Editora, 2010).

What was so appealing about Macpherson’s Bard? Being the last of his race, he presents tragic love of epic dimensions; heroism with nationalistic undertones; scenarios of the ‘sublime’; faithful commitment; passion; premature death; joy of grief. More than enough reasons, perhaps, to explain the female fascination for Ossian in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Ossian’s popularity becomes only too evident when we consider the many woman translators who contributed to the numerous translations of Macpherson’s publications and their lasting impact. Schiller’s wife, Charlotte von Lengefeld (1766-1826), and Karoline von Günderrode (1780–1806) showed a preference for ‘Darthula’, a short Ossianic poem included in the volume Fingal (1762). The Marquesa de Alorna (1750-1839) translated ‘Darthula’ into Portuguese, making use of Le Tourneur’s version of 1777. In her posthumously published translation she emphasizes ‘the melancholic tone in all of Ossian’s compositions, which mainly derives from the description of nocturnal scenes, lingering with pleasure on sombre and majestic objects’. [i]

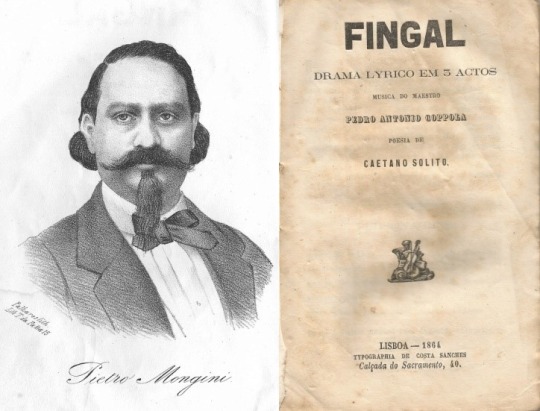

By the time Fingal was translated into Portuguese the previously politically controversial national epic had become less polemical through the different emphasis given by its reception abroad and through its musical treatment. Composers such as Désiré-Alexandre Batton (Fingal (1822), Caterino Cavos, (Fingal i Roskrana, a three-act opera, 1824) and Gaetano Solito (Fingal: dramma lirico in tre atti by posto in musica dal Maestro Pietro Antonio Coppola, 1848), applied the genre of romance or scène lyrique to the poems and transformed Fingal into a lyrical piece.

Besides the many woman-translators, the performing of Ossian as a musical piece also contributed to giving the female voice more prominence in the drama and narrative. Clara Novello’s acclaimed soprano made her one of the greatest British vocalists of her time from 1833 onwards. Amongst the most important works created expressly for Novello was Fingal by Coppola, a popular work which was a success for the singer, as she recollects in her Reminiscences:

Several operas have been written for me: “Fingal,” by Coppola, successful; “Cleopatra,” by . . . laughed off the stage; “Foscarini,” by Coen, not bad nor ill-received, and others I forget. A hospitable custom in Lisbon gave us all three or four days’ lodging in some hotel, during which to find permanent abodes for our six months’ stay. [ii]

Clara Novello.

Coppola’s Portuguese libretto of Fingal (‘drama lyrico em 3 actos’, 1851) emphasizes the female role of Agandeca (sic), which gains a disproportionate importance, compared with Macpherson’s text. Coppola’s piece was put on stage on 21 April 1851 in the Royal Theatre of S. Carlos in Lisbon, repeated nine times and brought back in 1864 for another two presentations.

The Portuguese libretto of 1864 with P. Mongini as Fingal.

By that time, however, the leading figures and opinion-makers of Portuguese Romanticism, Almeida Garrett and Alexandre Herculano, had already adopted a more critical view of Ossian. Herculano did not include Fingal in his canon of ‘truly original epics’. [iii]

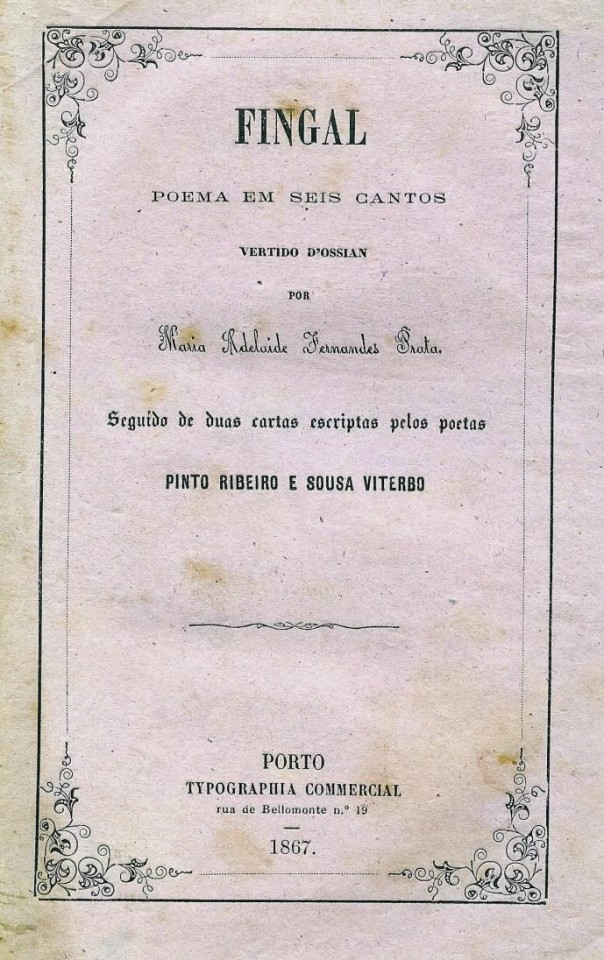

The first complete Portuguese translation of Fingal was published in 1867 in Porto by Maria Adelaide Fernandes Prata (1826-81), prefaced by two letters of the poets Pinto Ribeiro and Sousa Viterbo:

Porto edition of Fingal (1867).

It is possible that she had been inspired for her work by Novello’s performance or by its reviews. Similar to the Marquesa de Alorna’s Ossian translation, it too is reliant on Le Tourneur, who had used the 1765 Works edition, but it includes neither Macpherson’s notes, nor his Dissertations. In his eulogy Pinto Ribeiro considers Prata’s translated verses to be of the highest harmony, asserting that only a woman can produce real poetry. She can compensate for ‘formal defects with the grateful perfume of love and belief, fanciful lyricism, exquisite sensitivity and sentences of naïve simplicity, which male poetry can never achieve’. As he classifies Fingal not expressly as an epic poem, but as ‘one of the most beautiful little poems of the Homer of the North’ (‘um dos mais bellos poemetos do Homero do Norte’), the translator’s supposed childlike feminine ingenuousness seems to match the attitude expressed in natural and original, ‘formless’ folk poetry. Prata’s versification makes Sousa Viterbo rave about the ‘pure seraphic language’ of the ‘Scottish Homer’, with ‘its dithyrambs’ composed ‘of tenderness, melancholy, softness, delirium and passion’ (Prata, p. 14). These observations by the eminent poet Sousa Viterbo carry the weight of nineteenth-century gender and genre expectations. As already mentioned, the Portuguese Fingal does not include any of Macpherson’s notes, and excludes his and Blair’s academic dissertations. Categorising Fingal as ‘rather a lyrical than an epic poem’, Sousa Viterbo’s contribution to the volume thus relieves the translator of the supposedly masculine task of providing a lengthy literary-historical introduction to Fingal or having to supply academic notes. Its narrative, suspended by songs, and its descriptive elements always giving way to recitative parts, makes him ‘think more of the Romantic genre than of classic style of Antiquity’ (Prata, p. 16).

After appreciating the translator’s excellent choice and the accuracy and elegance of her work, Sousa Viterbo embarks on a detailed and effusively enthusiastic examination of Ossian, ‘the great poet’: ‘He has the roughness of primitive ages but it is this roughness that makes the heart a slave and the intellect a convinced admirer’ (Prata, p. 10). In his nineteenth-century view concerning the subject’s suitability for the fair sex, the poem’s ‘lyrical’ and romantic character, its inherent melancholy, the themes of love and poetry and ‘the female figures, so delicately and sensitively outlined’ by Ossian, makes Fingal perfectly suited for women translators. When Adelaide Prata’s translation came out the Ossianic subject had certainly changed from epic to epigonal, a fact made evident by many imitations and re-mediations (operas, theatre plays). However, despite the somewhat double-edged praise for its female translator, the Portuguese Fingal never saw a second edition, although the first was rather limited, inexpensive (500 réis) and inconspicuous compared to the impressive volume of 1762 (4to., 22.75 x 20cm), printed for Becket and De Hondt, in the Strand.

[i] D. Leonor D’Almeida Portugal Lorena e Lencastre Marqueza D’Alorna, Obras Poeticas, 6 vols (Lisbon, 1844), III, p. 289.

[ii] Clara Novello, Clara Novello’s Reminiscences. Compiled by her Daughter Contessa Valeria Gigliucci, with a Memoir by Arthur D. Coleridge, (London, 1910), pp. 138-146.

[iii] Alexandre Herculano, Opúsculos, edited by Jorge Custódio e José Manuel Garcia, (Lisbon, 1986), V, p. 213.

0 notes

Text

Ossian in the Balkans, Asia Minor, and Africa in the Nineteenth Century

This guest post by Kathleen Ann O’Donnell reports on some of her recent articles, which examine The Poems of Ossian in diverse Greek and Mediterranean contexts.

Accusations of fraudulence clearly deliberately dampened the power of The Poems of Ossian by James Macpherson. Only years of diligent research, started in Galway in 1993, began to reveal how his poetry, used in the name of peace and brotherhood, could also be used to expose the rapacity, belligerence, and diplomatic machinations of Western monarchy, particularly that of the British Empire in the Balkans and Anatolia. After completing my dissertation on ‘The Poems of Ossian and the Quest for Unity in the South-Eastern Balkans and Asia Minor in the Nineteenth Century’, I was affiliated to the British School at Athens, and presented papers at conferences in Oxford, Berkeley, Edinburgh, Besancon, Messalonghi, Cardiff, Albania and Athens. As I continued my research in this field I collected Modern Greek translations of texts from The Poems of Ossian, as well as Romanian translations by a Greek-Wallachian scholar, Ion Heliarde-Radulescu, which were circulated in Transylvania and Athens. This blog outlines some of the political purposes Macpherson’s poetry was put to in the centuries following publication.

Ossian Obscured: the Greek Case

In 1967, the article ‘Ossian in Greece,’ written by Nassos Vagenas, was published just as the military junta took power in that country. Vagenas states that the translator of ‘The Death of Calmar and Orla’, published in Evterpe in 1850, did not name his source. However, this is not the case. Byron’s name clearly appears on the translation; and this misleading statement served to sever any connection between Byron and Ossian made in the 1850 translation. Furthermore, ‘Ossian in Greece’ contains little historical data. It describes the main Greek translator of Ossian, Panayiotis Panas, simply as ‘unfortunate.’ This is an understatement: Panas was a ‘radical romantic’ who was tortured under the English and exiled in 1856.[1] The article also fails to mention that ‘The Songs of Selma’ were introduced into Athens through French translations of The Sorrows of Young Werther by J. W. Goethe in 1843. Further research revealed that by ignoring the role of nineteenth-century Greek scholars and translators of Ossian in contributing to the enrichment of Modern Greek, credit for the recycling of Ancient Greek words and neologisms from this work was instead ascribed to later Greek poets including Cavafy. This scholarly article thus led to the earlier origins of Ossianic influence being obscured.

Nicolai Abildgaard, Fingal Sees the Ghosts of His Ancestors in the Moonlight (1778)

Ossian in the Balkans

Ossian’s Greek translator Panayiotis Panas also spent almost a third of his life in Romania, working as a journalist. His political tendencies were clear: he was the only reporter to write on the Paris Commune in 1871, where the majority of supporters were Proudhonians, advocates of Mutualism. Moreover, Panas dedicated the second half of his book of poetry to Gustave Flourens, a colonel in the Communes murdered by French monarchists in captivity in 1871, as was Pierre Leroux, translator of Werther.

In secret, Panas set up the Democratic Eastern Federation (DEF) in Athens in 1868 under the guise of the Rigas Association, named after Rigas Velestinlis who had established a similar secret organisation in Bucharest in 1780. Thomas Paschides, an Epirot scholar and journalist, likewise founded an arm of the DEF in Bucharest in 1868. This organisation deployed translations of certain extracts from The Poems of Ossian as inspirational texts, designed to unite previous foes and to mobilise resistance to the imperial ambitions of Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russia and England in the Balkans. The most relevant translation is that of ‘Oina-morul,’ published in the periodical Byron on February 14 1876. Ossian’s magnanimity is depicted as he forfeits his reward – Oina-morul – so that she can marry her beloved enemy and cement peace. The poem also includes a footnote after ‘the race of Trenmor’ – “they are not cruel and unreceptive to political organisations” – which aligns Ossianic heroes with the noble members of the DEF. Ironically, on this same day, the peace agreement known as the Andrassy Note was signed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russia and Germany in the wake of uprisings in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1875. The reforms proposed gave equality to all creeds in the zone. However, the British Prime Minister Disraeli opposed the subsequent Berlin memorandum, and the subsequent collapse of the armistice resulted in the April Uprising of 1876 and the massacre of up to thirty thousand of Bulgarians. Such imperialism also ultimately thwarted the DEF’s “democratic, socialist, and nationalist ideals”.[2]

Ossian in Egypt

Following on from Panas’ revolutionary translations of Ossian I had a hunch about a particular extract from Book IV of Temora, which describes two brothers: the honest and just Cathmore, and the tyrannical Cairbar. Panas had moved to Alexandria when he published a book of poetry including an extract from ‘Temora Book IV,’ and the work was circulated in towns along the Nile and in Alexandria. Within this context, a political reading of the Temora extract would see Cathmor and Cairbar as standing for two rivals for the Khediveship of Egypt. These were Halim and Ismail, the son and grandson respectively, of Muhamid Ali, the Albanian Khedive and first ruler of modern Egypt. Both were vying for the Khediveship in Egypt while there was a coup d’état in 1865. British residents of the country including William Blunt (the so-called Byron of Egypt), and his wife, Anne Noel, scholar and granddaughter of Byron, shared similar beliefs to that of the diplomat William Gregory and his wife, Irish scholar Lady Gregory, whose abhorrence of British colonialism led to their support of the Egyptian Revolutionary leader Arabi. Seeking peace, Blunt exposed the duplicity of resident diplomats which England ignored. Instead, England bombed Alexandria and conquered Egypt. Both Lady Gregory and Blunt include Cuchullain in their works to express nationalist aspirations in the early twentieth century and the political use of Celtic myths can be seen in Panas’s translation of ‘The Death of Cuchullin.’ This translation was published in 1887 shortly after the occurrence of ‘Bloody Sunday,’ where a Socialist March in London protesting the arrest of Irish M. P. William O’Brien ended in violent clashes between police and demonstrators. The elegiac note found in so much Ossianic and Irish material resonated with the historical tragedies of the Balkans. Many supporters of the DEF were supposed to have killed themselves or were murdered and Panas published translations of the laments of ‘Minvane’ and ‘Lathmon’ from the Poems of Ossian to mourn such tragic deaths in 1890. Panas himself supposedly committed suicide in 1896, though the nature of all of these deaths is ambiguous and uncertain. These brief examples suggest that Ossianic and Celtic romanticism was influential in shaping and articulating expressions of political opposition to British Imperialism at its most Eastern perimeter.

My research, contained in the three articles below, describes how The Poems of Ossian have been largely ignored in the Greek and Mediterranean contexts until today and how this poetry was used to implement a Democratic Eastern Federation in the nineteenth century, whereby federations would be established to combat the threat of Western monarchy turning the zone into kingdoms under their control.

“How 20th Century Greek Scholars influenced the works of 19th century Modern Greek Translators of The Poems of Ossian by James Macpherson.” Athens Journal of Philology (December 2014).

“The Disintegration of the Democratic Eastern Federation and the Demise of its Supporters 1885-1896 and The Poems of Ossian.” Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies 2.2 (April 2016).

“The Democratic Eastern Federation and The Poems of Ossian: Egypt.” Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies 3.1 (January 2017).

[1] E. Stavropoulu, Panayiotis Panas (1832 - 1896). A Radical Romantic (1987).

[2] Loukis Hassiotis, Balkan Federalism - The social question and the national question in the idea of Balkan federalism from the 19th to the 20th century: a short survey. (2009), http://balkanbookfair.blogspot.com.au/.

0 notes

Text

The Social Networks of Ossian

The following is a guest post by Professor Ralph Kenna of the Statistical Physics Group at the Applied Mathematics Research Centre (AMRC), Coventry University.

A few years ago, and with support from the UK’s Leverhulme Trust, statistical physicists from the AMRC began a new type of investigation into epic literature. In contrast to more traditional literary and historical approaches, ours is quantitative. Instead of looking at individual characters or events, it focuses on the collected interactions and relationships between all of the characters in a narrative. Recently, and together with Justin Tonra from the Ossian Online Team at NUI Galway, we turned our attention to the poems of Ossian. Here, I describe why physicists are interested in such material, how we approached our investigations, and what the social network that forms the backdrop to the poems looks like.

The study of poetry and epic literature is about as far removed as you can get from the world of statistical physics. Yet there is a natural pathway that led us to Ossian. From the very beginning of their subject in the nineteenth century, statistical physicists have been interested in applying their wares broadly. Statistical physics was born from probability theory with its sibling sociology. In fact, an early term for that discipline was “social physics”. In the past couple of decades, sociophysics has re-emerged as a distinct branch of physics, dealing with how collective properties emerge in a population or a society. Physicists are very used to dealing with how collective phenomena emerge in materials that are not present at the level of the individual particles that comprise it. For example, water can freeze or flow but an individual molecule of H2O cannot; a hive of bees can swarm but an individual cannot. So, it is a natural step to apply the tools of statistical physics to societies. We go a step further and look at societies of characters in narratives, instead of societies of people in real life.

The statistical tools of choice come from network science, a recently developed sub-discipline associated with statistical physics. If two characters in a story interact or are related, they are deemed to be linked (just as two people in our society are linked if they know each other). We wanted to investigate whether networks in literature mathematically resemble social networks of real life or if they looked different. Initially we looked at networks in mythology (e.g., Beowulf, the Iliad, and the Táin Bó Cúailnge), but quickly we realised that we had developed an approach which is ideal for the analysis of Ossian.

The question we first asked was: what do the Ossianic social network structures look like? Macpherson and his supporters repeatedly compared the poems to Homer and deliberately tried to distance them from Irish sources, which they perceived as having less cultural capital. One of our questions, then, is whether this is manifest in the social networks; does the character network of Ossian compare to the Irish or Greek texts?

We have answered this question in our paper which will shortly be published in the journal Advances in Complex Systems. The answer is unambiguous; there is a remarkable similarity between the societal structure of Ossian and that of the narratives known as Acallam na Senórach (Colloquy of the Ancients) from the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology. Moreover, these look very different to the Iliad and the Odyssey. More details are provided in our paper.

Ossian network visualisation.

In this visualisation we present the character networks created and analysed by Joseph Yose, a PhD student at the AMRC. Besides facilitating answers to the above question, we hope they will inspire new questions and aid new research into other aspects of the Ossianic poems. We are currently investigating one such issue – what sort of process could be used to generate an Ossianic-style society from Acallam na Senórach? Besides being of interest to the humanities, such a question poses fascinating problems for mathematics and probability theory. We will deliver a second paper on these topics in due course. In the meantime, we are happy to answer questions and to engage in discussions about any aspect of this research.

Contact: [email protected]

Project team:

Ralph Kenna is a professor of theoretical physics at the AMRC and Co-Director of the L4 Collaboration & Doctoral College for the Statistical Physics of Complex Systems, Leipzig-Lorraine-Lviv-Coventry.

Pádraig MacCarron is a postdoctoral researcher at the Social & Evolutionary Neuroscience Research Group, Department of Experimental Psychology, Oxford.

Thierry Platini is a Senior Lecturer at the AMRC and L4.

Justin Tonra is University Fellow in English at the School of Humanities, National University of Ireland, Galway and co-PI of Ossian Online.

Joseph Yose is a PhD student at the AMRC and L4.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ossian, Albums, and Party Politics

A post by Rebecca Anne Barr on Ossian’s chequered reputation, reflected in the album of an eighteenth-century aristocrat. The album is housed in the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

The eighteenth century was full of albums. Avid readers and compilers, men and women from all walks of life transcribed, extracted, and collected items of intimate, ephemeral, or downright obscure interest. These albums were compendia of assorted tidbits reflecting individual friendships and connections (as well as topical material relating to celebrities), personal tastes and aspirations, assembled into compilations retained for pleasure or memory. As one romantic-era Russian commentator noted, the album’s sprawling structure enabled a ‘terrifying mix’ of poetry, prose, drawings, and musical notes to be ‘thrown together’ ‘without any order’.1 Then, as now, scrapbooks or albums were unified primarily by the character and lifetime of the compiler. One short occasional verse found in the album of Henry Temple, Second Viscount Palmerston (1739-1802), provides a pungent example of Ossian’s divided reputation amongst the English elite.

1766-1818 album compiled by Henry Temple, Viscount Palmerston. The mise-en-page gives a sense of the album’s heterogeneity. Lady Wortley Montagu’s despairing poem ‘With Toilsome Steps I pass’ is at the top of the page; the lines on Lyttelton are sandwiched between two light-hearted ‘epitaphs’: ‘Epitaph on a remarkable Eater of Oysters’ and ‘Epitaph’ on ‘an impious Wretch’. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Detail from the 1766-1818 album compiled by Henry Temple, Viscount Palmerston. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

On Lord Lyttleton’s [sic] Partiality to Fingal

Says the Peer who so lank is, so lean, and so tall,

What’s your Illiad or Aneid [sic], compar’d with Fingall?

No more he with Rapture the Classicks defends,

But forsakes his old Books, as he did his old Friends;

Prefers new Acquaintance in Party and Wit,

Macpherson to Homer, Newcastle to Pitt.

The hand is that of the Second Viscount Palmerston, father of the more famous nineteenth-century Prime Minister of England. The Second Viscount Palmerston, by contrast, was a clubbable, genial, and somewhat politically disinclined man given to literary and musical pleasures. Palmerston derived most of his income from his Irish estates, and was an archetypal absentee landlord, who declared the West coast of Ireland ‘the most desolate waste I ever saw’.2 His cousin George Lyttelton was a well-known politician and author, with the renowned Bluestocking Elizabeth Montagu, of the bestselling Dialogues of the Dead (1760).3

Unlike other sceptical contemporary readers of Macpherson’s work, we know that Lyttelton was an avid fan of the Scottish poet. He composed at least one Ossianic imitation for circulation amongst friends and averred that Macpherson was ‘the First Genius of the Age’.4 This love of Ossianic poetry may be traced to Lyttelton’s participation in Elizabeth Montagu’s group, since one of its Irish participants, Elizabeth Vesey, ‘played an important role in the coterie’s adoption of Ossianic tastes and practices’.5 Montagu herself described Macpherson’s works as conveying ‘ye noblest spirit of poetry’, and while this group of correspondents debated the origins of the verse they warmly celebrated its aesthetic quality.6

The author of this doggerel thus makes clear his insider knowledge of the lord’s literary passions and pursuits, suggesting an intimate connection to the ‘lank…lean and…tall’ peer whose gaunt looks were often lampooned in contemporary cartoons. Yet though the writer of the poem is acquainted with Lyttelton’s literary interests, he clearly does not share his approval of Fingal (1762), since he makes the politician’s ‘partiality’ to Fingal symbolic of his political treachery. In 1754 Lyttelton enraged a close cohort of his family, a ‘patriot’ group called the ‘Cousinhood’, who opposed the administration of the duke of Newcastle. Lyttelton, despite his longstanding family ties, accepted the role of chancellor in Newcastle’s ministry and was subsequently vilified by his former friends and relatives.7 Therefore, the wry parallelism of the poem’s final couplet – ‘Prefers new Acquaintance in Party and Wit, / Macpherson to Homer, Newcastle to Pitt’ - makes poor aesthetic judgment synonymous with political disloyalty. Espousing ‘Party’ or political faction is a deplorable come-down for one so previously high-minded as Lyttelton. The verse economically suggests that a man once known for his patriotic politics now prefers a parvenu Scotsman to the authentic virtues of Homer and Virgil. During these decades Scotophobia was rampant in London, so to be allied with a Scottish poetaster was deeply suspect and a potential sign of political self-interest.

This short, acerbic verse thus deploys Ossian as a cultural shorthand for shallow and self-interested sentiment. Lyttelton, it asserts, has thrown over classical principles for mere fashion. In this aristocratic album, the literary preference of a politician for Fingal is deployed as a marker of both political disloyalty and faulty taste.

--

1 N. Virsheeskii quoted in Justyna Beinek’s ‘“Portable Graveyards”: Albums in the Romantic Culture of Memory.’ Pushkin Review 14.1 (2011): 35-62. 35. Beinek’s article and Ellen Gruber Garvey’s Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 2013) are helpful introductions to understanding such resources.

2 Brian Connell, Portrait of a Golden Age: Intimate Papers of the Second Viscount Palmerston (The Riverside Press, 1957), p. 352.

3 Christine Gerrard, ‘Lyttelton, George, first Baron Lyttelton (1709–1773)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17306, accessed 25 July 2016].

4 George Lyttelton to Elizabeth Montagu,

October 18, 1763, Montagu Collection, Huntington Library, mo1315.

5 Betty A. Schellenberg, Literary Coteries and the Making of Modern Print Culture: 1740–1790 (Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 63.

6 Montagu Collection, Huntington Library, mo 1505.

7 Gerrard, ODNB.

0 notes

Text

Comala and Nina: Operatic Performance in the Age of Sensibility

Details of a forthcoming symposium with Ossianic resonances in Vadstena, Sweden. Abstracts for papers on Ossian by Howard Gaskill and Magnus Tessing Schneider can also be found below. Attendance at the symposium is free. For further details, contact magnus.tessing.schneider [at] teater.su.se.

This scholarly symposium, which takes place in Vadstena on 6 August, is organized by the research group Performing Premodernity on the occasion of the Vadstena Academy’s double-bill production of two little known Italian operas: Pietro Morandi’s Comala (Naples? 1780) and the one-act version of Giovanni Paisiello’s Nina o sia La pazza per amore (Naples 1789). The symposium centres on the issues of sentimental dramaturgy and vocal-dramatic performance practice in Italian opera in the decades up to the French Revolution. Comala and Nina can both be described as ‘avant-garde’ works in this regard. With a shared focus on the two works, a number of international scholars will explore the relationship between cultural and aesthetic theory, dramaturgy and audience involvement from the perspectives of different disciplines (comparative literature, theatre studies and musicology), examining such questions as: how can we describe and understand the aesthetic effect of these operas? How do the dramaturgical innovations affect performance practice? How are the artistic developments related to tendencies within the aesthetic, psychological and social theories of the Late Enlightenment? How may the operas throw light on the cultural climate of the 1770s and 80s?

Johann Peter Krafft, Ossian and Malvina (1810)

Howard Gaskill. “Why Ossian? Why Comala?”

The publication of James Macpherson’s Ossianic poetry in the 1760s proved to be a sensation of the first order, exerting an extraordinary (and by no means short-lived) impact all over Europe and beyond. This paper will look at some of the reasons for Ossian’s near-universal appeal, not the least of it being its intrinsic literary qualities. A purportedly ancient work, it served to promote innovation, particularly in Germany, the true home of Romanticism, but also in Italy where Melchiorre Cesarotti’s celebrated translation (1763) provided a shot in the arm for Italian poetic diction. However, Macpherson’s protean creation also appealed, in Italy as elsewhere, to those of a more conservative bent. Comala, the first of the shorter poems in the original English editions, came to be particularly popular in various incarnations, including the musical stage.

Magnus Tessing Shneider. “Staging Obscurity: The Transformation of Ossian in Ranieri de’ Calzabigi’s Comala.”

One of the most radical theatre makers of his century, Calzabigi is primarily known for the collaboration with Christoph Willibald Gluck. In 1774, he turned from the Greek and Roman classics to Ossian, however, converting the ‘dramatic poem’ Comala into an opera libretto, which was set to music in 1780 by Pietro Morandi, in strict accordance with the principles of the Gluck-Calzabigi reform. Unlike many contemporaries, the poet seems to have realized that the Ossianic Comala was essentially a closet drama, unfit for theatrical representation, and that it was necessary to rethink the work fundamentally to make it stageworthy while preserving what he called the “sublime but savage” quality of Ossian’s poetry. The latter is reflected in a manifest sense of non-communication and psychological obscurity, which was hardly compatible with the operatic conventions of the time.

0 notes

Text

‘Ossian in the Twenty-First Century’, Forum Issue of the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies

The following is a guest post by Dr Sebastian Mitchell (University of Birmingham), editor of the new forum issue of the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies. A subscription is required to view some of the content of the issue.

It’s been twenty years since the appearance of Howard Gaskill’s edition of The Poems of Ossian with an introduction by Fiona Stafford. The Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies is publishing this month a forum issue, entitled ‘Ossian in the Twenty-First Century,’ to celebrate its anniversary. Howard produced the first modern authoritative version of The Works of Ossian (1765), with a substantial textual apparatus and glossary. And with the support of his publishers, Edinburgh University Press, he was able to do so in paperback and at an affordable price. If you had any interest in Ossian before 1996, then you were more or less reliant on one of the many editions which were published from the end of the eighteenth century until the early twentieth century; and nearly all of those were based on the translator’s significantly revised and patently inferior version from the early 1770s. In the days before the virtual presence of Eighteenth Century Collections Online, and long before the welcome advent of Ossian Online, Gaskill’s edition spurred scholarly discussion of the poems. And, of course, in this respect it can be seen as being complementary to Howard and Fiona’s own academic writings, to his extensive accounts of the bard’s reception in Europe, and to her seminal revisionist biography of James Macpherson, The Sublime Savage. However, the edition’s publication also encouraged the reading of Ossian beyond scholarly circles, as the poetry began to be taught on undergraduate courses, and inspired a number of contemporary British artists.

Title page of a Gaelic edition of The Poems of Ossian (1807)

The forum issue considers the critical trajectory of the study of Ossian since the 1990s, and extends the discussion of the poetry in terms of its intrinsic value and cultural impact. The issue has an introduction, six articles by established and emergent Ossianists, and a short afterword by Howard. In the opening essay, Dafydd Moore rethinks the generic frameworks of the poetry, proposing Attic tragedy in place of epic; Nigel Leask examines Ossian’s Gaelic toponyms to suggest that the poetry provides a rather more ambiguous legacy than straightforward justification for the depopulated Romantic vistas of the Highlands; Victoria Henshaw traces Macpherson’s relationships with other translators of Gaelic verse; Juliet Shields challenges the received opinion that women are disposable secondary figures in Ossian; Gerald Bär tracks the southern transit of the poetry into the Iberian peninsula in the extracts in Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther; and Murdo Macdonald considers the visual interpretation of the works, including a recently discovered Ossian landscape by J. M. W. Turner. Howard brings proceedings to a close by reflecting on modern Ossian and the Johnsonians with his customary blend of energetic polemic and assured scholarship. The context for these contributions is provided by the editor’s introduction, which also speculates as to how the study of the bard might develop in the short to medium term, and how any print edition might fare in the modern era of digital scholarship.

0 notes

Text

Donation of Ossian Editions to James Hardiman Library

The Ossian Online project recently donated three Macpherson editions to the Special Collections section of the James Hardiman Library at NUI Galway. The donation includes copies of the first and second editions of Fingal (both dated 1762) and a copy of Temora (1763), and represents the beginning of an initiative to acquire copies of the seven editions that were published under James Macpherson’s authority in the period 1760-73. This will provide a printed analogue of the editions that comprise the focus of Ossian Online and create a new collection unique in the libraries of Ireland.

The edition of Temora donated to the James Hardiman library.

While part of the motivation for Ossian Online is to make facsimiles and accurate transcriptions of the full Ossian corpus available on the web, the project recognises that this is a representation of—not a substitute for—the original print editions. Just as the digital medium enables new orientations towards literary texts—such as the platforms for visualising genetic textual development and collaborative annotation being developed by Ossian Online—the printed book offers opportunities for scholarship that are unique to that medium. Individual copies bear marks of ownership and use—bookplates, signatures, marginalia—that allow scholars to investigate the social history and provenance of the work. During the era of handpress printing, variations between individual copies within a single edition were common, and surveying multiple printed editions can unearth this evidence—and reveal the circumstances behind such phenomena—in a way that a representative digital facsimile cannot. Forthcoming posts on this blog will examine some bibliographical problems that arise from examining multiple printed copies of Ossian.

Ossian Online team (Justin Tonra, Rebecca Barr, David Kelly) peruse Temora.

Thus, we are delighted to see NUI Galway take the first steps towards acquiring a printed collection to complement the work of Ossian Online. These editions were acquired with the assistance of funding from the School of Humanities at NUI Galway and the Irish Research Council, and the project would like to acknowledge their generosity in helping to establish this important initiative. Thanks also to John Cox, Librarian, and Marie Boran, Special Collections Librarian at the James Hardiman Library for their support in this endeavour.

0 notes

Text

Hello world

Welcome to the Ossian Online blog! Here you can expect to find posts on a range of topics: updates about developments on the Ossian Online website and news about the project; posts about current research on Ossian and James Macpherson; notifications about events, publications, and related Ossianiana.

If you have a topic, event, or publication that you would like to feature on this blog, please contact the Ossian Online editors at justin.tonra [at] nuigalway.ie.

1 note

·

View note

Text

New Approaches to Ossian

Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 4 September 2015

Dublin’s Royal Irish Academy was a fitting venue to reconsider the impact, meaning, and future study of James Macpherson’s Ossian poems. The 1772 ‘Committee for Enquiry into the Antiquities of Ireland,’ which fed into the founding of the Royal Irish Academy in 1785, was partly a response to the Celtic phenomenon fomented by Macpherson’s Gaelic epic. Participants and audience were not only from Ireland, however, with representatives from America, Scotland, and England testifying to the international impact of the Ossian poems.

The opening presentation by Justin Tonra introduced the audience to the IRC-funded project, Ossian Online. Opening with an overview of the eighteenth-century publication history of the Ossian poems, Tonra then traced the evolution of twentieth-century editions of Macpherson’s work. Tonra emphasised the importance of Howard Gaskill’s 1996 Poems of Ossian in providing a much-needed accessible scholarly edition at a time when national independence movements in both Scotland and the continent made study of this foundational document of European Romanticism particularly urgent. After discussing the digital edition’s expanded capacities for displaying textual issues, Tonra explained the logic for soliciting crowdsourced annotations on the text. Partly in the spirit of Ossian’s participatory composition but also as an acknowledgement of its multidisciplinary and transnational appeal, the site will enable users to comment on and annotate passages of interest or importance. The presentation concluded with a demonstration of the site in its current form with its complete archive of editions, including digital images, TEI-encoded text and its annotation tool. The ‘comprehensive availability’ of the edition had obvious advantages for readers, with the online resource moreover avoiding the ‘baggage of authority’ which print editions often problematically import to an unsuspecting readership. He explained the ways in which Ossian Online was not a critical edition in the conventional sense, and that the annotations would respond to the needs and commentary of those interested in and working on Macpherson’s poetry rather than imposing one specific scholarly framework or authoritative set of interpretations upon the texts.

The questions and comments from the audience confirmed both the risks and potential benefits of reconfiguring Ossian in the context of digital editions and crowdsourcing in particular. Dafydd Moore questioned the applicability of conventional academic vocabulary to the project’s aims, noting that its open-ended and participatory aspects pointed toward a ‘more radical’ goal than that indicated by the term ‘edition.’ Kristin Lindfield-Ott wondered about ‘the public at the heart’ of the project, and the need to consider which audiences the site would speak to – general, scholarly, or undergraduate? The vigorous participation from the audience in this opening session confirmed that in its new digital form the Ossian corpus still has the capacity to provoke debate.

Session One

Domhnall Uilleam Stiùbhart’s paper discussed contemporary Gaelic folksong as a neglected source for Macpherson’s ‘ancient’ epic. Emphasising the ‘multilingual Atlantic Archipelago,’ Stiùbhart looked at the relations between eighteenth-century Gaelic popular folksong later anthologised in collections such as Finlay Dun’s Orain na h-Albain and the Rev. Thomas Sinton’s Poetry of Badenoch on the one hand, and its counterparts (and to some extent origins) in Lowland Scots and English pastoral art song on the other, in shaping a set of tragic tropes which inspired Macpherson’s works. Tragic love narratives, the eroticisation of Highland males, multiple gendered voices, and the mix of ‘hard and soft primitivism’ typical of Macpherson’s work are also evident in an array of contemporary folksongs. Above and beyond Derick S. Thomson’s approach, one that derives Macpherson’s English-language Ossianic texts from corresponding Scottish Gaelic ballad sources, at another level Macpherson’s works are imbued with subjects, structures, and moods arising from contemporary Gaelic oral song culture, a culture that the poet himself participated in, collected, and may have contributed to, as a young man. Stiùbhart explicated the ‘hallucinatory repetitiveness’ of such tragic songs as accumulated in later anthologies, and stressed the key significance of the allusiveness of traditional Gaelic folksong – the fact that singer and experienced audience together know the unsung story that lies between and beyond the lines of the lyric – in helping us to recalibrate the influence on James Macpherson of his native Scottish Gaelic culture.

Dafydd Moore’s paper on ‘Caledonian plagiary’ in Macpherson raised the familiar, yet still contentious, issue of the relationship between Irish and Scottish ‘sources.’ Moore started by acknowledging that Macpherson’s treatment of Ireland was ‘fundamentally colonialist’ but that despite the attacks on Irish bards found in his supplementary dissertations the poetry itself expressed a much more subtle and sympathetic relation to Irish myth and legend, and indeed between the ‘ancient’ peoples of Ireland and Scotland. Conducting a close reading of the poetry itself, Moore looked at the quasi-erotic representation of Fingal and the remarkable ‘moments of reciprocity’ between Fingal and Cuchulainn which undercut any simplistically antagonistic relationship between the two cultures. Indeed, ‘Ireland was the arena where Caledonian virtues are tested and found wanting.’ Instead, Moore argued for the structural impact of the colonial relations in the text, with issues of monarchical succession and colonial expansion being worked through in the poems. The subtle and sympathetic representations of Ireland in the poetry provided a salutary lesson in the necessity of reading beyond the anti-Irish polemic of the dissertation and textual apparatus, rather than trusting that these ‘editorial’ pronouncements reflect the actual content of the poems themselves.

In the discussion, James Mulholland remarked that Moore’s close reading exposed the ‘extraordinary demands’ Ossian placed on the reader, not merely in deciphering the terms of relationships between characters and plotting, but also of rhetorical position – who is speaking is rarely immediately clear.

Session Two

Ralph Kenna opened his and Joseph Yose’s presentation on network analysis of Ossian by explaining the contexts in which mathematicians and physicists are interested in literature and and contextualising their approach inside the broader relationship between science and humanities. Joseph Yose continued the paper by outlining the preliminary results of the project’s investigation of the network structure of Ossian. Their work is primarily focussed on comparative mythology and epic narratives, and considers the nature of the social networks in Ossian and their similarity to those in a range of epic narratives including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and tales from the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology. Initial results indicate that the Ossianic networks (characterised separately and collectively as friendly and hostile interactions between characters in the narrative) share significantly greater structural similarities to the Irish epics than to the Greek. How these insights might translate to our broader understanding of Ossian, its sources, and Macpherson’s shaping role featured prominently in the discussion of the paper, while the broader opportunity for scientists and humanists to share perspectives and interpretative methods was an edifying outcome of the presentation.

Kristin Lindfield-Ott’s presentation ‘James Macpherson in the Highlands – Public Engagement Beyond Public Lectures’ emphasized the ways in which academic research was solicited and generated by a general audience in the Highlands. Rather than following the conventional ‘outreach’ routes, where the university attempts to disseminate specialised knowledge to the community, Lindfield-Ott argued that current initiatives in Scotland provided an instance of a contrary direction. She discussed Highland communities’ interest in the author of Ossian, and his works, as part of a living cultural tradition, where clan identity and history, and an ongoing revitalization of the intellectual and cultural activities in the Highlands and Islands gave this eighteenth-century figure genuine public interest. Discussing the variety of community engagement undertaken by Lindfield-Ott and colleagues at UHI, including education days, a public festival, and university courses which introduce students to Macpherson’s work, she emphasized the gains to be made from treating Ossian not as an academic monolith but as an opportunity for participatory engagement and widening access: a vision of literature and history in which the academy and the public are equal partners.

Finally, Sebastian Mitchell’s contribution reflected on the current and future state of scholarship on Ossian. Acting as an introduction to the forthcoming special issue of the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies Mitchell provided an overview of recent work pursuing new lines of enquiry in Macpherson’s oeuvre. Rather than treating Ossian as a ‘hollowed out cultural phenomenon,’ Mitchell argued that recent work suggested the continuing fecundity of the text itself: returning to Macpherson’s poetry not only opened new avenues of interpretation but restored a sense of the dynamic capacities of the writing. For Mitchell, the aesthetic polyvalence of Ossian was clear in the new work on its influence in music, art, as well as translation studies. The special issue of the journal marks the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of Howard Gaskill’s edition of The Poems of Ossian, and Mitchell provided a timely reminder of the importance of that volume in reinvigorating Ossian scholarship and of the importance of continued attention to the textual issues that proliferate throughout the Ossianic corpus.

Roundtable

Rebecca Barr emphasized the movement away from questions of authenticity and source-tracing in recent work on Macpherson, describing Ossian itself as a project of remediation that worked at the interface between cultures. By refashioning older forms, by altering and remodelling historical oral and lyrical sources, Ossian thus initiates a ‘making new’ which transforms the past and intervenes, decisively, in the aesthetics of its time. Such remediation, she argued, was paralleled by the Ossian Online project. Thus, it reproduces the historical forms of Macpherson’s editions in digital images, while reconfiguring them into new textual and digital formats via TEI encoding. As Michael Suarez has argued, digitization does not recreate print material but transforms it into a different object altogether. So, while Ossian Online offers an ‘archive’ as part of its remit it also changes the very material it presents via its representation and recontextualization of Macpherson’s poems. Just as the symposium provided a space for questions to be raised, and sometimes answered, so the online site could function in a similar manner. What kind of reading might occur, she asked, in this new format? In a pedagogic context, asking who, what, where, and why would help both educators and student readers to assess the text interactively.

Opening with a reflection on the impact of Macpherson on reception studies in Ireland, Lesa Ní Mhunghaile noted the omnipresence of Macpherson’s influence in Charlotte Brooke’s preface to Reliques of Ireland – but Brooke’s telling, and perhaps paradigmatic, elision of Macpherson as influence. Ní Mhunghaile noted Michéal MacCraith’s foresight in using Macpherson’s work as a teaching text for students of Irish Studies and the Irish language, but emphasized a continuing dearth of interest in his works by Irish Language scholars. Ní Mhunghaile argued that much was still to be gleaned on the reception of Ossian in Ireland: while native response to Macpherson’s slights against the Irish is well known other repercussions of Ossian’s popularity could be pursued. Following a line of thought raised by Stiùbhart’s earlier paper, Ní Mhunghaile wondered whether the popularity of particular Irish lays could be linked to Ossian. His role in ‘mediating the Celtic world,’ she suggested, gave his work a deep significance in the context of the Irish marketplace. Extending earlier discussions of orality and print, Ní Mhunghaile argued for the ‘reciprocal interactions’ between manuscript, print and oral culture, as readers transcribed elements from printed works, which entered manuscript culture which then fed back into printed works. There was, she put forward, ‘ample opportunity for Irish scholarship to contribute’ to the future tracing of source material and to facilitate the cross-referencing of sources.

Clíona Ó Gallchoir’s lively contribution gave insight into the impact Macpherson’s Ossian had upon Irish writing in the long-eighteenth century and upon the novel and women’s writing in particular. Paying respect to the groundbreaking work of Clare O’Halloran and Katie Trumpener in examining the cultural politics of Ossian, she suggested that revisiting Macpherson in a new light could help ‘rescue a period of enormous condescension in the writing of Ireland,’ including works of aesthetic and national importance which continue to be underexplored by academics. Reconsidering Macpherson in a new Irish context could give rise to work on Irish song, for instance, in tandem with research in Scots-Gaelic. Treating the textual effects of Ossian might allow critics to ‘reimagine relations’ between Irish, English and Scottish writers, and Ó Gallchoir noted Ossian’s impact in shaping aesthetic preferences in the half-century following his work. Though Macpherson may have accompanied his Celtic rhapsodies with anti-Irish polemic, Ossian’s substance and style enabled self-presentation and authorship for many Irish writers. The nationalist sentiments of many women writers, such as Lady Morgan, were apparently energized rather than disabled by Macpherson’s work. Ó Gallchoir discussed the dismissal of Macpherson’s Ossian as deriving from the same kind of cultural embarrassment as that which greets other ‘inspirational’ forms of writing, such as fantasy – which similarly elicits imitative compositions from its fanbase. Ó Gallchoir concluded by suggesting that the history of reading may provide one of the most fecund avenues for future research into Ossian: not merely the responses of literary or historical personages, but ordinary women readers whose participation contributed Ossian’s success and whose experience of the work may lend insight into the very reasons for its subsequent marginalization.

Public lecture

James Mulholland opened his public lecture by borrowing from Susan Stewart the concept of the ‘distressed genre’ – a mode of writing that adopts a deliberately antique posture. While Stewart sees this tactic as an imposture in her account of Crimes of Writing, Mulholland uses it as a cue to theorise an ‘archive of the inauthentic’ consisting of impersonations and representations of ethnic voices in the eighteenth century. Repositioning of what we now call (and might condemn as) cultural appropriation allows Mulholland to compare Macpherson’s Ossian with other ‘impersonated’ voices of the period. Singing and oral performance are crucial to the mode of Ossian, but not directly to the structure of the work (form produces orality; not vice versa). Macpherson invited readers to imagine themselves as auditors of an oral phenomenon which self-consciously played with its components. He counterpointed Macpherson’s work with a set of anonymous ‘Tahitian translations’ of the 1770s: comedic satires in the persona of native Tahitians, whose publication in Britain coincided with Cook’s voyages to the Pacific. Criticism of the verses characterised them as tedious and repetitive, and bad doggerel: but Mulholland argued that the elements that prompted these criticisms were deliberate parts of a strategy of impersonation and virtualisation. The circuitous textual transmission presented by the title pages of these poems – often ‘translated’ or ‘transfused’ by comically-named Irish professors – contribute to the air of deliberate inauthenticity and the pleasures of knowing impersonation. Ossian and these pseudo-pornographic poems testify, in diverse ways, to the ways in which comparative orality in the eighteenth century was capable of both provoking virulent response and the reflexive thrill of impersonation.

The organisers would like to thank all the symposium participants for their contributions to the event. They would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Irish Research Council’s New Foundations scheme; School of Humanities and Moore Institute, NUI Galway; the Digital Repository of Ireland; the Royal Irish Academy; the National Library of Scotland.

0 notes