Text

U ever get so mad.that ur teenhood was wasted being a wreck

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

If you see this

You were visited by the magic kitten of rest. Reblog to have a good night’s sleep.

693K notes

·

View notes

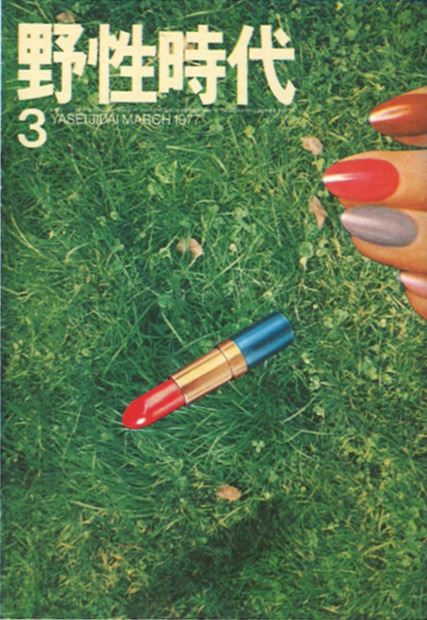

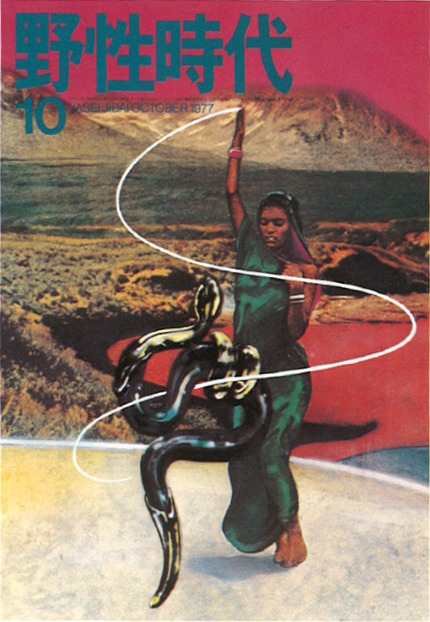

Photo

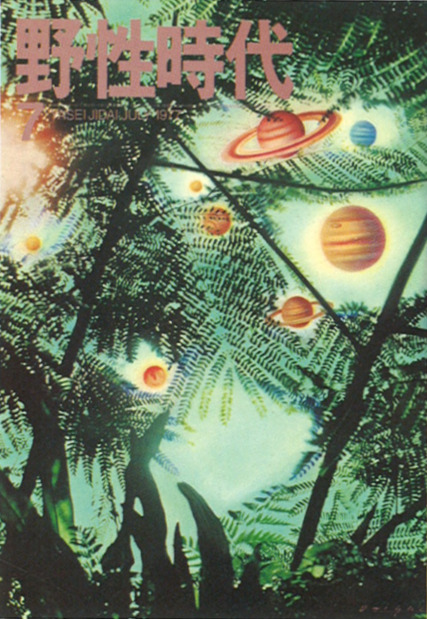

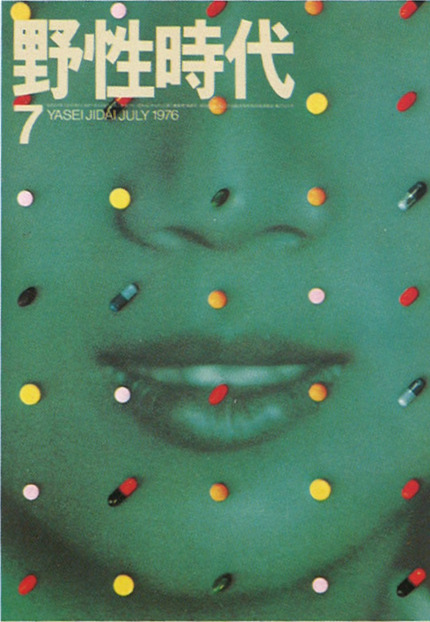

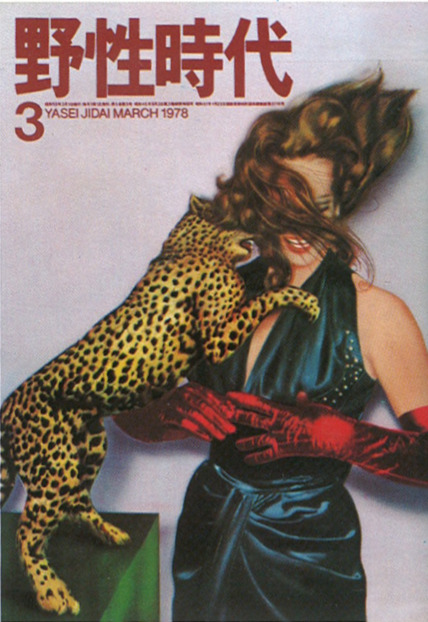

1970s Covers of Yasei Jidai Magazine, Art Direction by Eiko Ishioka

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t speak because I have the power to speak; I speak because I don’t have the power to remain silent.

Rabbi A.Y. Kook

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

concept for kirby star allies: third party dream friends

18K notes

·

View notes

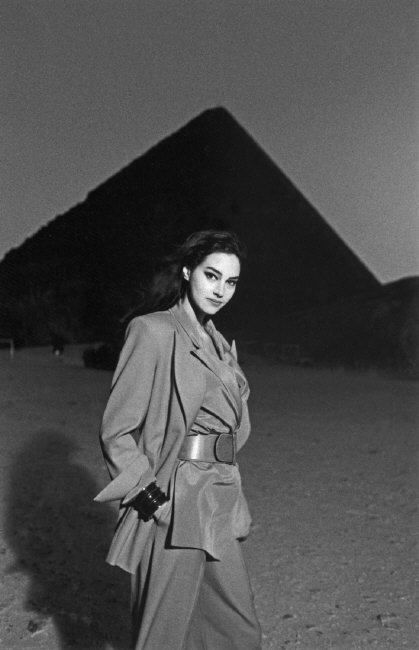

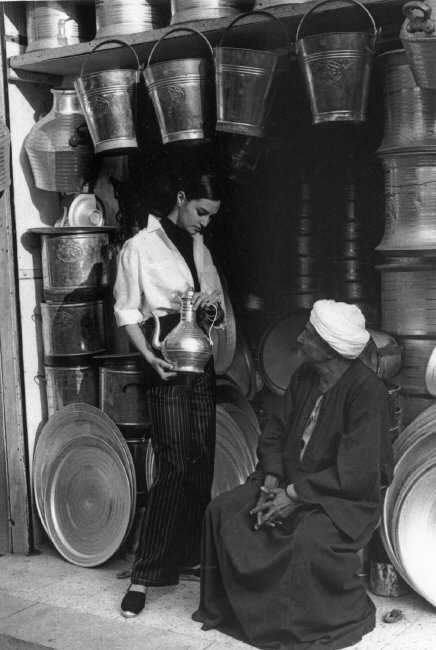

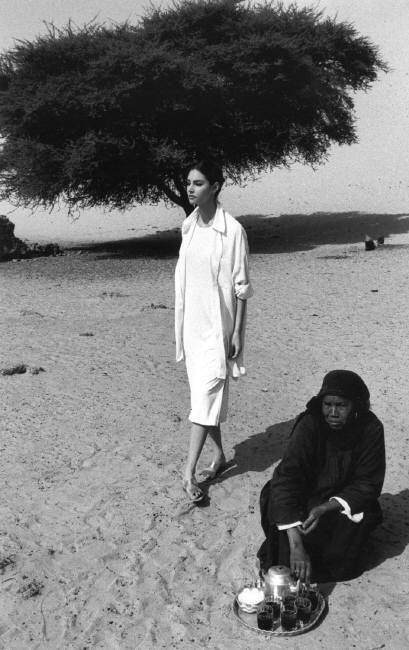

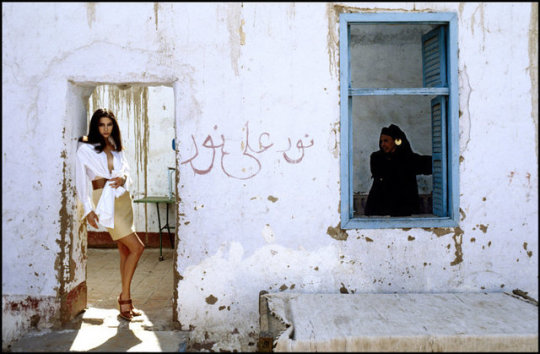

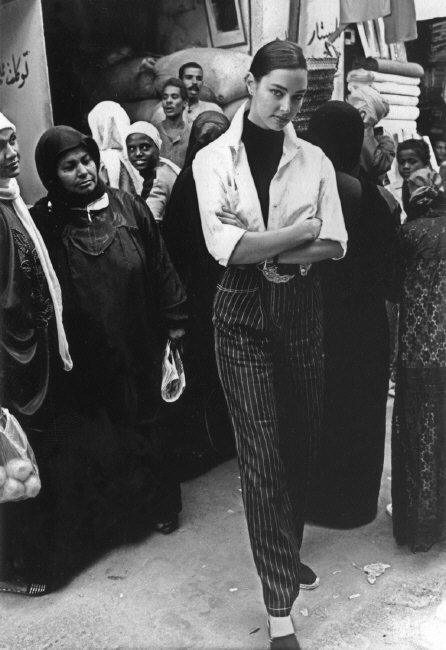

Photo

Fashion story with Stacey NESS by Ferdinando Scianna

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Stop letting your heart and your pussy choose your men.

629K notes

·

View notes

Text

real power is going outside knowing you look ugly and also knowing that if you chose to perform femininity in accordance with patriarchal standards you could look attractive, but genuinely prefering to look ugly and not feeling bad about it. feels good feels organic

131K notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt(s):

“How strange it is to see one’s own life played out by outsiders, acting against a monochromatic Golders Green neighborhood, coupled with the eerie music of a horror film. A packed house of mourning, the Gefen matzo meal on the window sill. The sea of black hats. The airlessness of patriarchy. The colorless kosher grocery and the ill-fitting clothes. The women’s balcony, and the suffocated eyes of Esti, as she peers out from underneath her quite-convincing wig, a caged animal.

Enter Ronit, the film’s breath of fresh air, the New York-based photographer who has broken free from the shackles of tradition. At the Sabbath table, she retorts to an older woman at the table, “Maybe you should stop having so many children!” The audience at Tribeca guffawed at her super-sharp retort: You go girl. Keep telling those baby-making machines to stop breeding. The schadenfreude in those laughs was palpable.

Later, as the two women walk down the street, Ronit asks, “Do you guys have sex every Friday?”

“It’s expected,” Esti answers, nodding somberly. In that moment, she could have been Elizabeth Moss in the Handmaid’s Tale.

“Medieval,” Ronit huffs.

In the comfortable reclining seats at Regal theaters in Battery Park, I sit in a wig no different from Esti’s, next to a row of stretched-out denim-clad legs, laughing at Ronit’s flippant defiance of the community, sighing at Esti’s suppressed desires. And all I can think is: What do you know? What do you really know of our lives? Do you really understand the secrets of my life?

[…]

Have you ever lived a life that is punctuated by prayer and blessing? Have you ever spent an hour swaying and clutching a prayer book, your seventeen-year-old heart filled with hope? Have you ever gone on a shidduch date and told yourself you should just marry him, because you’re 22 already? Have you ever said the Song of Songs for forty days straight in the hopes of getting married?

And then: Have you ever bought a wig for the first time, nervous but also excited about the status, the glamour, that is promised to a married woman? Have you ever woken up and realized that you’re totally illiterate in Talmud, that men’s realm so long forbidden to you, the cornerstone of your religion? Have you ever gone to the mikveh after childbirth and broken into tears, overwhelmed by the tiny child now entrusted to you? Have you ever found yourself irritated by the uniform imposed on you, dreaming of dressing like the rest of the world — and in the next moment, loving the secrecy of your headcovering, the humility it inspires in you, the way it constantly reminds you of who you are? What do you know?

I suppose it is titillating for a secular audience to watch the rebellion of the pure virginal rebbetzin. Because in a culture where all is permitted, religious women are the last line of defense, the last Austen-like setting in which there are rules to be broken, in which something is still forbidden. Oh, and combine that illicit love with a cantor singing the mournful ‘El Male Rachamim’ and some shots of austere women in dark clothes, and that’s all you need for critics to laud it as ‘powerful’.

Sorry, but that’s too easy. It is much harder to create art that is authentic without the melodrama.

This is unfortunate because, indeed, there are plenty of utterly heart-wrenching stories in our community — including the experiences of gay members, who will often suppress themselves for the sake of conformity. But here, there was no complexity; religion is simply a source of oppression. There is no joy, no solace, no intellectual curiosity in Judaism; very little is keeping Esti tethered to her community. It’s black and white, good guys and bad guys.

Not all cinematic representations of Orthodox life are doomed, however. Some of the best pictures of frumkeit are coming out of Israel today. In television, “Shtisel”, the drama about a family in Mea Shearim, accomplished this beautifully, while the recent comedy about yeshiva students, “Shababnikim”, hit the nail on the head with social satire. In film, Gidi Dar’s “Ushpizin’”wowed audiences because of its precise tender rendering of a fervently Orthodox couple facing barrenness. Rama Burshtein’s ‘Fill The Void’ won several Ophir awards (the Israeli Oscars) because it showed a community in full color, unflinching from both the pain and the beauty.

But somehow, American attempts seem to fail — perhaps because, unlike Israeli filmmakers who actually live alongside and engage with the Orthodox, and increasingly include Orthodox artists among their ranks, Hollywood still looks at us like we belong in zoo-like display cases.

“Disobedience” and its ilk make for cultural appropriation at its finest: It peddles stereotypes, painting an extremely complicated community in broad strokes, with soapy drama and tears.”

I’m not saying that everything about this article has the last word or is infallible, and I’m not completely dismissing any shred of value or decent execution Disobedience might have, but this critique hit home hard and as someone who is Jewish, gay, and has experience in orthodox communities (and still longs for them frequently despite disconnect, disagreement and problems I have faced). I find myself agreeing with almost everything written here. I think anyone who is 1) not jewish or 2) a jewish person who has never been up close to orthodoxy should at least read it, chew it over and allow it to complicate their experience watching and responding to this film.

596 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bat Mitzvah Girl Lighting Sabbath Candles, Ceuta, Morocco, 1979

1K notes

·

View notes