Text

"The Lost Gallery"

I have come across a Scandal in the world of online historical portraiture. Apparently, some time ago, someone went through Wikipedia and updated a bunch of pages of historical nobility with allegedly contemporary, or at least posthumous, portraits. Subsequently, these portraits were picked up by other sites, and even used as references for art.

BUT. Let's take this portrait of Blanche I of Navarre, which I had long admired:

Beautiful, right? I wonder where it came from. Let's run it through a reverse image search:

It's a Photoshop job, taking this original picture, St. Catherine by Luini Bernadino, and adding a different head and the Navarrese coat of arms. Once you see it, it becomes obvious: the hands and face don't even match.

Here's another, an image titled "Eleanor of Navarre" alongside this painting of Mary Magdalene:

Looking through the Wikipedia edits page in the arguments to remove these images, it turns out that these fakes all come from one source: a now defunct Flickr page called "The Lost Gallery." Whether they had intended to pass off their images as real, or whether someone else had accidentally picked them up, is unclear. But the damage has been done, and you can find tons of historical women whose public face is now decided by these random images. When you're looking for sources, run a reverse image search to make sure it's the real thing.

Here are some more to look out for that had me fooled:

(Not Blanche II of Navarre, Catherine I of Navarre, or Marjorie Bruce)

(Not Anne of Cyprus, Isabella of Angoulême, or Arthur I of Brittany)

If you spot any more, feel free to add them to the list, and maybe we can go some ways toward clearing this up.

879 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Sicily’s women have always been shadowy figures, crouched quietly in doorways or gazing down the crowded streets from balustraded or shuttered windows. For most of the medieval period they have left no direct record of themselves, since, with a few exceptions, they could neither read nor write - and even the possession of literacy, for those few lucky enough to enjoy it, did not give one the right to act or speak independently. As a consequence, very few records survive to shed light on their activities, and virtually none of the records we have present the women in their own voices. In the intensely conservative society of Sicily, women lived their lives under tight constraints; the traditional roles that society gave them gravely limited their freedom to act and ours to behold. Local customs, in general, were designed to isolate and protect women from the outside world, to keep them safely ensconced in their fathers’ homes until they could be safely and just as absolutely ensconced in their husbands’ homes, or, for the devout and dowry-less, dedicated to God in a nunnery. Not until the Vespers era - an era inaugurated with a rebellion sparked by an Angevin outrage against a native woman - do Sicily’s women come into view with any meaningful detail of focus. Our view of them is still partial and imperfect, given the limitations of even this improved documentation. But the extant evidence holds a few surprises.The most visible figures belong of course to the aristocracy. After 1282, and as a result of it, Sicily’s queens played important roles in society. The Catalan dynasty placed the bulk of its claim to the throne on its marriage link with Constance, the last of the Hohenstaufens. Consequently, the right to inherit title and property through the female line was well established. Frederick’s and James’s father, although he had conquered the realm and had received the acclamation of the Communitas Sicilie, consistently emphasized his right to rule through his marriage to Constance; and Frederick too, as we saw earlier, asserted his inheritance of Constance’s patrimony, rather than his election by parliament, as the chief legitimation of his kingship. As queen, Constance began the practice of sitting in the MRC and taking her place in the king’s inner circle of advisers. Extant records show her working to reconcile the church to the new dynasty, to foster greater unity of action among Sicily’s contending factions and regions, and to educate the new ruling caste to Sicilian customs. When Peter left the island in order to tend to matters in Catalonia, Constance headed the lieutenancy council that governed the realm in his absence; and she continued to advise the throne during James’s reign. As late as 1296 her aid was still sought by those who wanted to influence decisions at court, although the extent of her influence by that time had clearly waned.Frederick’s wife Eleanor likewise was a member of the council and exerted a fair share of influence. As with Constance, this influence had more to do with economics than ideology. As independent ruler of the camera reginale, the queen controlled a large segment of the vital Val di Noto, the most important city in which was Siracusa, with a steady population of nearly 8,000 throughout the reign. Adding the other sites that made up the apanage, she ruled a population of some 20,000 individuals. Her camera was the site of two of the most important trade fairs - at Siracusa, beginning on the Feast of the Nativity of the Virgin, and at Lentini, at the Feast of the Ascension - and represented as well a significant venue for wine, grain, and salt exports. Siracusa itself, in fact, held a monopoly on all exports from the confines of the city northward through all the coastal territory of the Gulf of Augusta. So important had the city become as a trading center, especially for the eastern and southern trade routes connecting Sicily with Greece, Egypt, and Malta, that the Siracusan salma was made the standard measure for all agricultural produce in the eastern half of the kingdom. In 1299 the government awarded the city a toll franchise that freed its produce of the inland duties levied upon other domestic trade; the franchise was to be lost, however, if the land under the city’s control was alienated or enfeoffed. This resulted in a rather static social structure, since land seldom changed hands. In later years, when the queen wanted to reward anyone or felt the need to make additional grants in order to purchase loyalty, she circumnavigated the prohibition of alienating the land by granting instead various rights (pasturage, herbage, water access, etc.) over the land, but not the land itself. The general strength of the commercial economy, however, made Siracusa, and the entire camera, for that matter, an attractive site for the thousands who fled the decay and poverty of the Val di Mazara. It was the sole region in the kingdom that experienced an increase in its population, in absolute numbers, during Frederick’s reign.Eleanor held full powers of criminal and civil jurisdiction over the district, and, through her hired agents, administered an independent machinery of tax collection. Few records survive from her administration. But what evidence we have indicates that she took her responsibilities seriously, even though she did not always choose well in appointing her officials. A personal favorite whom she introduced at court in 1307 and to whom she entrusted some minor diplomatic errands, Pere Ferrandis de Vergua, proved to be a flatterer and opportunist, a corrupt official who wooed and wedded a series of wealthy widows and young heiresses. On Eleanor’s recommendation, the MRC appointed Pere Ferrandis royal tax collector for Caltavuturo, where his flagrant abuse of his position led to vehement popular protests and ultimately to his impeachment; and when Pere later was found to have forged a number of documents - most notably his first wife’s will, arranging a bequest of 2,000.00.00 to himself - he was banished from the realm. Ultimately, he conspired to murder Frederick, whom he blamed for his failure to win the position in society that he felt he deserved.Eleanor was intensely pious. From the day of her arrival in Sicily - she married Frederick as a stipulation in the Caltabellotta treaty - she threw her considerable energy into rebuilding thekingdom’s shattered churches and monasteries, and to raising new houses, hospitals, and evangelical schools. She funded the construction of Castrogiovanni’s duomo in 1307, according totradition, by selling the entire collection of her royal jewels. She generously endowed any number of religious houses, within her camera and without. In the area around Paterno, for example, shegranted lands, curial rights, and cash to the monastery of S. Maria di Licodia, in return for the monks’ prayers on behalf of the royal family. The gift was prescient, in its way, since Frederick died inPaterno while en route to Castrogiovanni. Her advocacy for religious houses continued well after their founding and endowment. Especially in the case of nunneries, Eleanor remained involved in their daily lives by observing elections to abbacies, the recruitment of nuns, the regularity of their worship, and their treatment of relics. She visited nunneries throughout the realm, often with her children in tow, and regularly participated in their worship, showing an early preference for Franciscan houses.Above everything else, she seems to have considered it her fundamental responsibility to promote religious observance and moral reform. Although overt, specific evidence about her relationship with the evangelical movement is lacking, a number of clues survive that show her to have been an enthusiast for the Spirituals. We have seen already that she took seriously Arnau deVilanova’s injunction that she and her handmaidens should perform public rituals in every duomo and hospital in every city they visited, dressed as personifications of Faith and Hope, “so that inthis way the people may have a vision [like that] of the Mother of God entering a place of misery to comfort those who are there.” It was probably in such garb that she led the procession of the relics of St. Agatha around the confines of Catania, during the eruption of Mount Etna. She not only held vernacular readings of the Scriptures on Sundays and feast days, but she further commissioned a vernacular translation of the Dialogues of Gregory the Great, for the edification of the royal children, one of the few substantial texts in Sicilian dialect that survives from Frederick’s reign. Even in a mundane duty like appointing a new bailiff to preside over her territory at Paterno her concern for the spiritual life of the community dominated all other considerations. When she appointed Ruggero Gala to be bailiff, in 1311, at the height of Sicily’s flirtation with Arnau’s prophesies of the kingdom’s apocalyptic role, she specified that his first and foremost duty was “that he should take diligent care, if he should find anyone blaspheming against God, the Blessed Virgin, or the saints, or anyone speaking ill of the Royal Majesty, that he should take no sureties [i.e. promises to appear in court as summoned] from them, but should immediately seize their persons and take them captive to the justiciar of the province.” Under Sicilian law, most accused criminals had the right to post bail and remain free until their trial; but the passionate atmosphere of the evangelical realm would permit no such freedom to those who were even rumored to be guilty of blasphemy. In lock-step with Arnau’s teachings and the Ordinationes generates, the queen directed her bailiffs also to arrest anyone caught playing at dice or cards. But Eleanor, for as much as she helped to establish a general atmosphere of family concern and reformist piety, was merely one woman, and hardly representative of the majority.”

Clifford R. Backman, The Decline and Fall of Medieval Sicily. Politics, religion, and economy in the reign of Frederick III, 1296-1337, p. 285-290.

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“But it happened that some merchants from Gaeta, who had gone to Sicily to buy grain, spoke in front of the Queen about the riches of Manfredi Chiaramonte, and about the beauty of a daughter of his. Whence the Queen’s wandering mind stopped to think to ask for the girl’s hand on behalf of her son, the King Ladislao, who was already fourteen [sic] years old.”

in Angelo Di Costanzo, Historia del Regno di Napoli dell'Ill. Signor Angelo di Costanzo, Gentil’huomo e Cavaliere Napolitano, p. 237 [my translation]

Costanza was born around 1377 (probably in Palermo) from the noble and ancient family of Chiaramonte. She was the daughter of Manfredi III Chiramonte, IX Earl of Modica and Duke of Malta, and his wife, Eufemia Ventimiglia. Costanza’s father was a powerful man, who, during his lifetime, would hold high profile roles, such as Admiral, Grand Seneschal, Master Justiciar and Regent of the Kingdom for young Queen Maria of Sicily. From her mother side, she was the granddaughter of another former Regent, Francesco II Ventimiglia, Earl of Geraci.

In 1389 Margherita of Durazzo, Regent of the Kingdom of Naples, asked fellow Regent Manfredi Chiaramonte for Costanza’s hand on behalf of her son, the twelve years old Ladislao of Anjou-Durazzo. Three years prior, after his father Carlo III had been murdered, Ladislao failed to be recognized by Urban VI as legitimate King of Naples. The Pope had assigned the throne to Louis II of Anjou, whose father had previously (in 1380) been adopted as son and heir by the childless Queen Giovanna I of Anjou-Naples in an attempt to block the rival Anjou-Durazzo’s claims to the Neapolitan throne. In 1387 Louis II’s troops invaded the Kingdom of Naples, so young Ladislao, alongside his mother, the rest of the family and court, was forced to seek refuge in Gaeta.

If the Chiaramontes’ social status benefited from the newly acquired (although wobbly) royal connections, the Anjou-Durazzo made good use of the bride’s rich dowry to replenish their worn-out coffers. Their economic situation was so dire, the University of Gaeta had to act as a guarantor and advance the sum of 15 thousand gold florins on behalf of the royal family, which would have been handed to the bride’s family in case of non-consummation of the marriage and consequent dissolution of the union. In summer 1389 Costanza then arrived in Gaeta by sea escorted by galleys. These same vessels managed successfully to break the chains which locked Naples’ harbour and bring relief to the Durazzo forces besieged in Castelnuovo.

In October of the same year, one of Ladislao’ enemies, Urban VI died. Unlike his predecessor, Boniface IX favoured the Durazzos since the Anjou supported the Antipope Clement VII. As also the Chiaramonte backed the newly elected Pontiff, the union between Ladislao and Costanza received Clement’s blessing. The marriage between the now recognized King of Naples and the Sicilian noblewoman (they were both 13 years old) finally took place on August 15th 1390 (the marriage settlement probably dated back to September of the previous year). The religious ceremony was immediately followed by a joint crowning ceremony.

This union would prove to be short-lived as Chiaramontes’ fortunes were about to change. Costanza’s father, Manfredi died in 1391 and was succeeded by his kinsman, Andrea Chiaramonte, X Earl of Modica. That same year, Queen Maria married her second cousin Martino the Younger of Aragon. In the eyes of the majority of the Sicilian nobles, Martino was a stranger (despite being, like his wife, a descendant of Pietro II of Sicily) and his marriage to the Queen could (and would) have led to Sicily fall under a more direct control of the House of Aragon, with the consequent loss of influence of the Sicilian nobility. In the end, Andrea Chiaramonte was abandoned by his allies and found himself alone in trying to contrast the new King consort and his father, the powerful Infante Martino, Duke of Montblanc (and later King of Aragon and Sicily). The Earl of Modica was arrested, charged with treason and beheaded in Palermo, June 1st 1392.

With the decline of her family, the young Queen of Naples’ fortunes too deteriorated. The King had now no reason to be still married with the representative of a disgraced household. In May of the same year, Ladislao had travelled to Rome to obtain from the Pope the annulment of the marriage. The official motivation was the minority of the bride and groom. To make things worse, the Queen’s mother, Eufemia Ventimiglia, was accused of debauchery and to have become Infante Martino’s mistress.

In July 1392, the Pope conceded Ladislao the desired annulment, and the bill of divorce was read publically by the Bishop of Gaeta while the King and Queen were attending mass. The Bishop pulled the wedding ring from Costanza’s hand and handed it back to Ladislao.

Three years later, the King married his former wife to one of his vassals, Andrea di Capua, IV Earl of Altavilla (1374-1399). Costanza’s modest dowry amounted to 3 thousand ducats. According to tradition, she publically and disdainfully addressed her new husband telling him he could now brag he could call as his concubine his King’s wife. Costanza bore Andrea di Capua at least one son, Luigi (1400-1443), who will inherit his father’s titles and possessions. Costanza died in 1423 and is currently buried in the Church of the Madonna delle Grazie, in Riccia (n the region of Molise), together with her husband, son and the rest of the di Capua’s members.

As for Ladislao, in 1403 he would marry Maria of Lusignan, Princess of Cyprus and Jerusalem, but the new Queen would die the following year. In 1406 he would marry a third and last time, with Maria of Enghien, widow of Raimondo Orsini del Balzo, Prince of Taranto. The King of Naples would die 8 years later without legitimate children and the crown would be inherited by his sister Giovanna II.

Sources

- Salvatore Fodale, COSTANZA Chiaramonte, regina di Napoli in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani

- Angelo Di Costanzo, Historia del Regno di Napoli dell'Ill. Signor Angelo di Costanzo, Gentil’huomo e Cavaliere Napolitano

- Famiglia di Capua

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

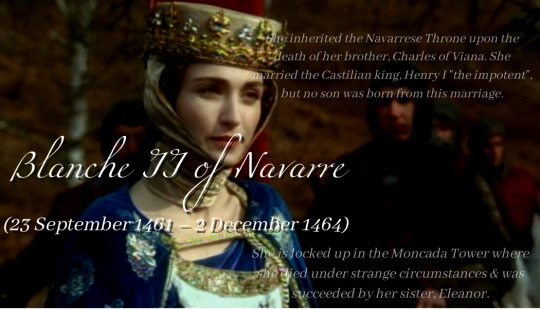

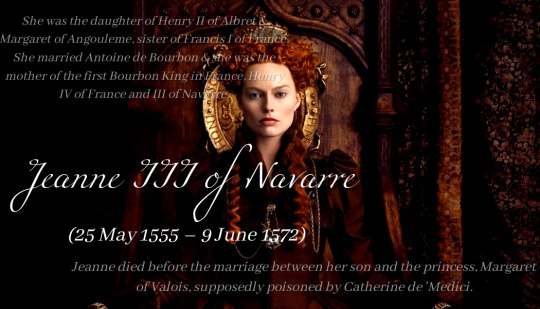

Titular Queens of Navarre

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

♕ English-born wives and queen consorts of Scotland

311 notes

·

View notes

Photo

♕ Scottish-born wives and queen consorts of Scotland

235 notes

·

View notes

Photo

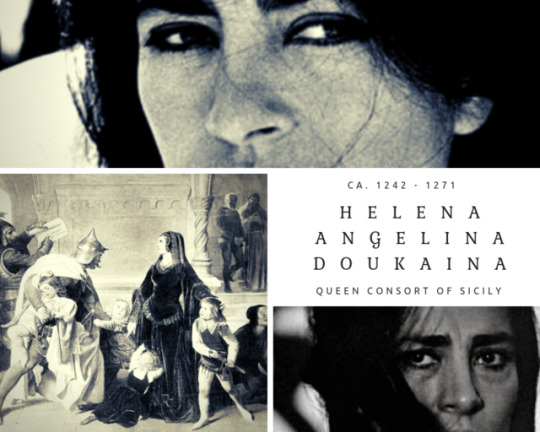

[…] On the second day of the month of june of the same year MCCLIX, arrived in Apulia with eight galleis the fiancée of the Lord King Manfredi, the daughter of the Despot of Epirus, named Elena, accompained by many barons and ladies-in-waiting of our Kingdom and that of her father’s […]

in Lorenzo Giustiniani, Dizionario geografico ragionato del Regno di Napoli, vol. 1, p. 231 [my translation]

Helena Angelina Doukaina was born around 1242 as the older daughter of Michael II Komnenos Doukas, Despot of Epirus and his wife Theodora Petraliphaina. Nothing is known about her life prior to the engagement to widowed Manfredi I of Sicily. Manfredi’s first wife, Beatrice of Savoy died at some point in 1259, bearing him only a daughter, Costanza, making the Sicilian King in serious need of a male heir.

Helena arrived in Apulia, to meet her future husband, on June 2nd 1259, she was barely 17, while Manfredi was 27. She was described as beautiful and graceful (in appearance superior to the King’s first wife), as well as good, wise and prudent. The wedding was celebrated in Trani with incredible pomp and solemnity. Although the exact terms of wedding pacts are unknown, Manfredi saw confirmed his occupation of territories near Durrës and Vlorë. Moreover, part of the princess’ dowry included Corfu, Buthrotum and Kaninë. In September of the same year, Manfredi joined his father-in-law and his brother-in-law William of Achaea (who had married Helena’s sister, Anna) in a war against Michael VIII Palaiologos of Nicaea. The coalition was defeated in the Battle of Pelagonia, thus paving the way for the reconquest of Costantinople and recover of Greece at the hands of Michael and his fellow Byzantinians (and making life even more difficult for Manfredi’s sister, Costanza, who had lived at the Nicaean court as an honorable hostage since 1254).

Historical sources offer little to no information about Manfredi and Helena’s married life. Even their children’s exact birth day isn’t recorded. However, it has been established that the firstborn was a girl named Beatrice, born around 1260. ”On May 3rd of said year MCCLXII, it was heard that on April 30th the Queen Elena gave birth. She delivered a baby boy, whom Lord King Manfredi gave the name of Enrico, like his grandfather, and so in our land many parties and many light displays were thrown”. It’s possible the child was born in Castel dell’Ovo, which at the time wasn’t still part of the city of Naples. Followed other two sons, Federico and Enzo (also mentioned as Anselmo or Azzolino). Their exact date of birth isn’t sure, it must have been a period between the end of 1263 to the whole year 1265.

Helena might have cared deeply for her step-daughter Costanza, loving the girl as she was her own child. In occasion of the princess’ marriage to future Peter III of Aragon in 1262, the Queen was described as dissatisfied about this match. When the Catalan dignitaries arrived to Manfredi’s court to bring the future bride back with them, she found them looking male in ordene e scontienti (messy and disgruntled). Moreover the marriage between the Sicilian princess and the Aragonese heir was disapproved by the Church and this worsened the already tense relationship between Manfredi and the Papacy.

As a matter of fact, in 1266 Charles of Anjou was crowned in Rome King of Sicily with the consent of Pope Urban IV. Manfredi was being de facto overthrown. In the attempt to preserve his position and stop Charles’ invasion, the deposed King clashed against his rival in Benevento but without success. On February 26th 1266, Manfredi lost his kingdom and his life. It was reported there were Greek soldiers who fought in Benevento on the Sicilian side, so they must have been sent by Helena’s father. Those who didn’t perish, they were captured by the French army.

In the meantime, Helena had previously taken refuge in Lucera with her children, her sister-in-law and former Nicaean Empress, Costanza, and perhaps also one of Manfredi’s illegitimate daughters, Flordelis. When news of the defeat in Benevento arrived, Helena and the children fled to Trani with the intention to reach Epirus. They couldn’t leave because of a violent storm and because of the betrayal of the lord of the castle, Trani was occupied by the Frenchmen. On March 6th “they [the soldiers] took her [Helena] with her four children and all the treasures she had with her, and during the night they took them away, no one knows where.” The Queen was soon separated from her family (whom she’ll never seen again) and alone was brought to Lagopesole to meet Charles. The Frenchman intended using the former Queen to tighten his relationship with her home country and might have asked her to transfer the ownership of Corfu and other lands which were part of her dowry to him. Helena refused since Charles didn’t offer her freedom for her or at least her children as counterpart. Needless to say Charles knew too well the danger of setting Manfredi’s (male) heirs free. Even though they were currently merely little kids (Beatrice was 6, Enrico 4 and the other two even younger), they would eventually grow up and challenge him. While Helena was held captive, there was talk of adventurer prince Henry of Castile’s intention to marry the widowed Queen. Henry was one of Charles’ supporters and had even lent him huge sums of money as well as helping him militarily. Moreover this possible match was seen positively by the Papacy. Nonetheless, the Anjou wasn’t risking letting Helena remarry into such powerful family.

In the summer of 1266, she was moved to the castle of Nocera Christianorum (now Nocera Inferiore), which was one of the most fortified and consequently secure fortresses in the Kingdom. Despite being a prisoner, Helena was treated with courtesy, having granted a certain amount of luxury and having access to her jewelry, rich clothes and precious furniture and furnishing. Clearly she wasn’t left alone, as Charles feared she would try to flee. He personally appointed a personal guard in 1267, a French soldier called Rodolfo de Fayelle or de la Faye (”We [Charles] want that the Rock of Nocera, with all its weapons and garrisons, and Elena, widow of Manfredi, will immediately handed over to Rodolfo della Faye”), who was later substituted by Enrico de Porta, castellan of Nocera.

In 1268 Charles defeated and executed Conradin, Manfredi’s usurped nephew and the rightful King of Sicily. Her presumed suitor, Henry of Castile, unhappy of Charles’ ingratitude, had changed sides and supported the Hohenstaufen heir (who was his relative on his mother’ side), but was taken prisoner in the aftermath of the Battle of Tagliacozzo. Helena’s chance to see her family again or return home were now null.

However, she didn’t live much longer. She must have died between February and March 1271, when she was barely thirty. Her servants and ladies-in-waiting were set free and her custodian, Enrico de Porta, drew up a list of her belongings dated July 18th, 1271.

Of her children, Beatrice (most certainly because of her sex) was the only one with whom destiny will be more merciful. After 1271 she was transferred to Castel dell’Ovo, where she lived as a prisoner (although treated with some respect like her mother was) until 1284, when she was liberated by Roger of Lauria, an Italian admiral in the service of Aragonese Kingdom, in the middle of the so-called Sicilian Vespers. Beatrice was taken to Sicily which had been occupied by her brother-in-law, Peter III, who had reclaimed the Crown on behalf of his wife Costanza. Beatrice will later become Marchioness consort of Saluzzo as the wife of Manfredi IV. Her brothers experienced a more tragic end. Enrico, Federico and Enzo were taken to Castel del Monte. Some sources attest Charles had them blinded, but it’s unsure. Certainly the Angevin King and his successors had hoped for Manfredi’s sons (and last rightful male heirs to the throne after Conradin’s death) to die of neglect and starvation and, most importantly, in oblivion. In 1300 they were moved to Castel dell’Ovo, under the order of Charles II of Anjou. Apparently Federico and Enzo died there within the short span of a year. As for Enrico, he died alone and miserable in October 1318, he was 56.

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dumque, toto jam regno in statu tranquillo salubriter stabilito, regem ipsum de remotis et exteris, ad quae jam suarum virium habenas extenderat, studium debitae curiositatis accingeret, parentelam cum rege Aragonum, tractatu hinc inde per nuntios praemisso, primordio contrahit, et filiam suam Constantiam, quam ex prima consorte sua Beatrice filia quondam A. comitis Sabaudiae, imperatore vivente, susceperat, domino Petro, primogenito dicti regis Aragonum, solemni matrimonio copulavit.

Saba Malaspina, Rerum Sicularum Libri, p. 229

Beatrice was the daughter of Amedeo IV, Count of Savoy, and his first wife Marguerite of Burgundy. Nothing is known about Beatrice’s exact date of birth or about her life prior her engagement to Manfredi III, Marquess of Saluzzo. In 1233, after a ten years long (and once broken) bethrotal, she became Marchioness of Saluzzo. While Manfredi was still alive, Beatrice gave birth to Adelasia (ca. 1236) and Tommaso (1239). The twins, Agnese and Margherita, were born posthumously in 1245. The Marquess in fact died in 1244. In his will, he had named his wife and his cousin as well as brother-in-law, Boniface II of Monferrat (he was the husband of Beatrice’s sister Margherita), as his children’s guardians.

Beatrice’s life underwent a sudden change when, in 1247, Frederick II King of Sicily and Holy Roman Emperor asked her father for her hand on behalf of his 17 years old (illegitimate) son Manfredi. The reason behind this proposal was, of course, merely political. The Emperor, excommunicated and officially (but not de facto) deposed by Pope Innocent IV since 1245, needed a way to secure his position in Northern Italy and a marriage was the easiest way to secure it.

In March 1247, Frederick sent Gualtieri d’Ocra (elected Archbishop of Capua) to negotiate with Amedeo of Savoy the marriage between Manfredi and Beatrice. The wedding pacts were sworn on April 21st 1247 at Chambéry. Amedeo IV was given back the castle of Rivoli and Beatrice would be granted a widow’s pension of 1000 silver marks per year. While Manfredi would receive the lands that went from Pavia and the Genoese coast up to the Alps, plus the Kingdom of Arles, with the consent of the earl of Savoy. The arrangements were formalized on May 8th. The marriage was celebrated in Vercelli at some point between the end of 1248 and the beginning of 1249.

Despite the importance of the match, Beatrice is barely mentioned by the historical sources. The only certain point is she gave birth to a daughter in 1249, the future Queen consort of Aragon (and later pretender to the throne of Sicily) Costanza. It isn’t even known the exact date of her death. No chronicle talks about her in occasion of her husband’s coronation as King of Sicily (August 11st 1258). Only bishop and historian Saba Malaspina, when talking about her death (although without specifying the date), calls her regina Beatrice in his Rerum Sicularum Libri (XIII century). It’s undeniable, though, she was already dead by the time Manfredi started arranging his wedding with the daughter of the Despot of Epirus, Helena Angelina Doukaina.

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

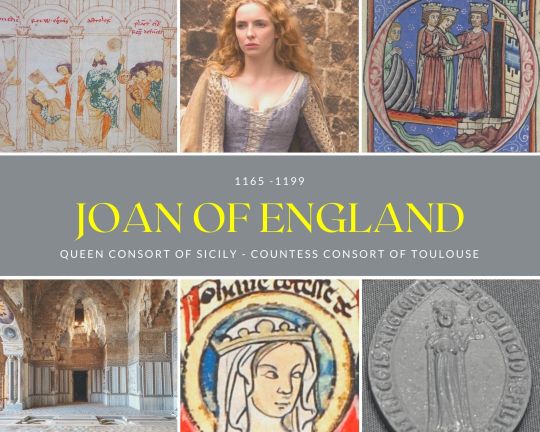

THE PLANTAGENET QUEEN CONSORTS OF SICILY - part 1

“Tanti ergo mysterii ratione, simul & veneratione inducti nos Will. divina favente clementia, Rex Siciliae, Ducatus Apuliae, & Principatus Capuae, Johannam Puellam Regii excellentia sanguinis illustrissimam, Filiam Henrici magnifici Regis Anglorum, divino nutu & felici auspicio, sacri lege matrimonii & maritali nobis foedere copuIamus, ut bonum conjugium castae dilectionis fides exhibeat; unde nobis in posterum proles Regia, Deo dante, succedat quae, divini gratia muneris, virtutum simul & generis titulo ad Regni possit & debeat festigium sublimari.”

in Foedera, conventiones, literæ, et cujuscunque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliæ et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices, principes, vel communitates, ab ineunte sæculo duodecimo, viz. ab anno 1101…, p.17

Joan was born in Angers, France, on October 1165 to Henry II, first Plantagenet King of England, and Eleanor, titular Duchess of Aquitaine (“Regina Alienor, mense Octobris, Amdegavis peperit filiam, et vocata est in baptismate Johanna.” in Chronique de Robert de Torigny, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel, I, p. 357). She was the seventh child (and third and last daughter) and, among her siblings, she could count future Kings of Egland, Richard I Lionheart and John I Lackland.

As a child, and together with her younger brother John, she was sent to Fontevrault Abbey (which benefitted from the Plantagenets’ protection and support), where she would be prepared for a bright future, possibly as a queen consort somewhere in Europe.

As a matter of fact, Henry had tried to marry her off to the Kings of Aragon or Navarre, although without success. In 1169, when Joan was still four, her father had begun negotiation to get his daughter engaged to Guglielmo II of Sicily. At first, even this attempt appeared to be fruitless, as the Sicilian King would have preferred to ally (via marriage) himself with the Byzantine Emperor, Manouel I Komnenos. As the Emperor got, instead, closer to Frederick I Hohenstaufen, Guglielmo resumed his negotiations with Henry II.

In 1176 Guglielmo of Sicily officially asked permission to marry Joan, who had at that time already left the Abbey and reached England. On May 20th of the same year, Henry officialized his permission and, by the end of August, Joan set off from Southampton, headed for her new Kingdom. After a difficult journey by sea (the future bride had to stop in Naples, where she celebrated Christmas), she finally reached Palermo in late January 1177.

Guglielmo and Joan got married in the Royal Chapel (it’s not certain if in Palermo or Monreale) and, on February 13th, Joan was crowned (together with her husband, at his second coronation) Queen of Sicily in Palermo’s Cathedral (“Convocatis autem rex Guilielmus Proceribus Sicilie et magna Populi multitudine, prenominatam filiam Regis Anglie in Cappella sua desponsavit, et se et eam gloriose coronari fecit, et sollemnes de illa nuptias celebravit Anno MCLXXVI, mense Februarii, Ind. X ” in Chronicon Romualdi II, archiepiscopi Salernitani, p. 41). Joan’s coronation should be considered a peculiar event for her time since it was already unusual for 12th-century queens to be crowned, but it was even rarer they got anointed with the holy chrism. Even though the joint coronation might lead us to think she would, from now on, regarded as equal to her husband, a co-regent, in reality, that ceremony was more a way to consecrate her role as a consort and (hopefully) mother of the future king. Guglielmo bestowed on his wife a rich dowry, worthy of a Queen, which included the lordship of Monte Sant’Angelo, the cities of Siponto and Vieste, the castles of Alesina, Pesco, Capracotta, Barano, Sirico and many other estates (“Comitatum Monti Sancti Angeli, Civitatem Siponti & Civitatem Vestae cum omnibus justis tenementis & pertinentiis earum. In servitio autem concedimus ei, de Tenementis Comitis Golfridi, Alesine, Peschizam, Bicum, Caprile, Baranum, & Sfilizum, & omnia alia quae idem Comes de honore eiusdem Comitatus Monti Sancti Angeli tenere dinoscitur” in Foedera, conventiones, literæ, et cujuscunque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliæ et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices, principes, vel communitates, ab ineunte sæculo duodecimo, viz. ab anno 1101…, p.17 ).

In his Chronica, Abbot Robert of Torigny records that Guglielmo and Joan had a son, Boemondo, who was invested by his father with the Duchy of Apulia (“Audivimus a quibusdam quod Johanna, uxor Guillermi regis Siciliae, filia Henrici regis Anglorum, peperit ei filium primogenitum, quem vocaverunt Boamundum. Qui cum a baptismate reverteretur, pater investivit eum ducatu Apuliae per aureum sceptrum, quod in manu gerebat.” in Chronique de Robert de Torigny, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel, II, p. 115). If Robert de Torigny is to be believed (which is unlikely), that would mean Bohemond died as an infant since Guglielmo died on November 18th 1189 without living issues (“[…] alteram duxit Siciliae rex Willelmus, qui prole caruit […]” in Matthæi Parisiensis, monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica majora, p. 326).

The lack of a direct heir gave rise to a succession crisis. The rightful heir was Guglielmo’s aunt, Costanza. What made Costanza’s claim less appealing in her future subjects’ eyes was her marriage to Frederick I Hohenstaufen’s son, Heinrich. To many, the perfect alternative to Costanza, a woman married to a foreign prince, was Tancredi of Lecce, the last (illegitimate) male representative of the Hauteville house in Italy. Taking advantage of the fact that Costanza and her husband were, at that moment, stuck in Germany, Tancredi was crowned King of Sicily in January 1190.

Having lost her role as a Queen consort, and lacking an heir which would have consented her to act as a regent, Joan was confined by Tancredi in the Zisa Palace, inside late Guglielmo’s harem, amid many Arab born beauties, and closely guarded by Muslim eunuchs.

In that same year, Joan’s brother, Richard (who had succeeded his father the year before), on his way to the Holy Land, arrived in Sicily (obligatory passage towards the Middle Eastern) together with French King, Philippe II Auguste. Richard demanded King Tancredi to release Joan, give back to her dowry (which had been seized by the Sicilian King following Guglielmo’s death) and financially support the Third Crusade as it had been previously agreed upon by the late king. At first, Tancredi ignored Richard’s requests, limiting himself to just deliver Joan to her kingly brother on September 28th. The English King retaliated by militarily occupying Messina, where he ordered the construction (or the renovation) of a wooden castle commonly known as Matagrifone (lit. “killing Griffones”, where the Grifoni/Griffones stands for Levantines and Greeks, as they were called by Northern Europeans) and from where his troops pillaged and massacred the population. The long sojourn in Sicily put a strain on the relationship between the two Kings, already so different (“The king of France, whatever transgression his people committed, or whatever offence was committed against them, took no notice and held his peace; the king of England esteeming the country of those implicated in guilt as a matter of no consequence, considered every man his own, and left no transgression unpunished, wherefore the one was called a Lamb by the Griffones, the other obtained the name of a Lion.” in The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes concerning the deeds of Richard the First, King of England, p. 17-18). Philippe Augustus didn’t approve of Richard’s behaviour and arrived to plot against him together with Tancredi. The tense situation led the two allies to meet to talk it out. They reached an agreement, which included the dissolution of the betrothal between Richard and Philippe’s sister, Alys, and the pledge to defend each other’s lands as if they were their own.

After a brief stay in Messina (and after, it is said, having charmed Philippe Augustus), Joan was sent by her brother on the other side of the Messina Strait, to the newly conquered Bagnara Calabra, where she was joined by her mother and Berengaria of Navarre, Richard’s new fiancée. Finally, at the beginning of March 1191, a treaty was signed between Tancredi and Richard. Tancredi had to reimburse Joan for her dowry (which the Sicilian King was going to keep) with almost 570kg of gold. Moreover, one of Tancredi’s daughters would in future marry Arthur of Brittany, Richard’s nephew and heir. If the marriage would never take place, the Sicilian King had to pay Richard a further sum of 570kg of gold.

In April 1191, the English party set sail towards the Holy Land (the Frenchmen had already departed). A storm dispersed the fleet, separating Richard from his sister and future wife. The women (and the treasure ship) reached Cyprus, where they were taken prisoners by Isaakios Komnēnos, ruler of the island. At the beginning of May, Richard arrived in Cyprus and demanded his sister and fiancée’s release. Since Isaakios refused, the English King attacked and occupied the island. The former ruler was forced to surrender, he was then imprisoned and shackled in silver chains since Richard had promised him he would not be put in irons. Before leaving Cyprus, Richard married Berengaria and sold the island to the Knights Templar. The English army finally arrived in Acre in June, accompanying (as a prisoner) them was the so-called Damsel of Cyprus, Isaakios’s daughter and heiress.

Arabic sources state that around September Richard had tried to come to terms with Salah al-Din, by offering his sister Joan as spouse to the Sultan’s brother, Al-Adil. The records add that this match was made impossible by the Christian clergy’s refusal to allow it without a pre-emptive conversion of the future husband (Joan’s objection to this union wouldn’t have mattered much), but Richard might have just tried to gain time since, when Salah al-Din accepted the offer, the English King backed off, stating they would need a Papal dispensation to let a dowager Queen marry an infidel. In lieu of his sister, Richard then offered his niece’s hand. At this point, Salah al-Din broke the negotiations.

Together with her sister-in-law, Joan left the Holy Land by the end of 1192 and most certainly lived with Berengaria until 1196, when she married (by order of her brother Richard) Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse and Marquis of Provence (“MCXCVI […] Eodem anno comes de Sancto Egidio duxit in uxorem Johannam sororem Ricardi regis, quondam reginam Siciliae……” in Annales Monastici, Annales de Burton, vol. I, p. 192). Raymond, nine years her senior, was at his fourth marriage. The union between the Plantagenet princess and the Count of Toulouse finally put an end to the families’ (Aquitaine and Toulouse) feud as Richard gave up on his claim on Toulouse.In 1197, in Beucaire, Joan gave birth to a son Raymond (“MCXCVII. Johanna comitissa de Sancto Egidio, soror Ricardi regis Angliae, peperit Reimundum suum primogenitum” in Annales Monastici, vol. I, p. 192), followed by, the next year, Jeanne (“V. Kal. Junii, Anno MCCLV, obiit illustrissima Johanna filia Raymundi Comitis & Regina Johanna, uxor quondam Domini Bernardi de Turre” Extrait de l’ancien Obituaire de l’abbaye de la Vaissi en Auvergne in Histoire Genealogique de la Maison D’Auvergne, p. 499). The marriage between Joan and Raymond is described by some as unhappy, but the reason behind it perhaps could be that, because he had shown certain sympathies towards the Catharism, Raymond was seen as a heretic. In his Chronique, 13th-century chronicler Guillaume de Puylaurens, writes how, pregnant of her third child, and intending to avenge the many injuries suffered by her husband by the hand of his enemies, she besieged the castle of Casser. Despite her good intentions, her expedition failed and so Joan ran to her brother Richard to ask for his help, to help and support her husband. It must have been a great shock for her when, along the way, she found out her brother was dead (“Comme sa mère était une femme énergique, prévoyante et ayant à coeur de se venger des offenses que bien des Grands et des Capitaines avaient faites à son mari, à peine eut-elle fait ses relevailles, qu'elle marcha contre le Sire de St.-Félix , et assiégea le château de Casser. Mais cette passer en secret aux assiégés des armes et ce qui leur était nécessaire. Vivement émue de ces menées, elle quitta le camp, dont elle fut à peine libre de sortir; car les traîtres mirent le feu à son logis, et elle s’ échappa au milieu des flammes. Poussée par le ressentiment de cette in jure, elle accourut vers son frère, le roi Richard, pour en obtenir satisfaction; elle ne trouva que son cadavre. Richard avait été tué à la guerre, et ce nouveau chagrin causa la mort de Jeanne.” in Chronique de Maître Guillaume de Puylaurens sur la guerre des Albigeois – 1202-1272, p. 20-21). According to the Annales of the Winchester Priory, Joan gave orders that the soldier who had mortally injured her brother was to be tortured, blinded, skinned and quartered (“[…]sed Marchadeus misit eum clam rege ad Johannam comitissam Sancti Egidii sororem regis, qui fecit ei evelli ungues pedum et manuum et oculos, et postea excoriari et equis detrahi.” in Annales Monastici: Annales monasterii de Wintonia, A.D. 519-1277, p. 71). John had succeeded his brother Richard on the throne, and Joan thought about asking for her other brother’s help. She reached him in Normandy, but all she could get was an annuity of 100 golden marks. Wearied and heartbroken, she felt her end was near and, despite being married and pregnant, she asked permission to take religious vows and become a nun in Fontevrault Abbey. Despite some initial reserve, after seeing how determined she was, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter, caved in and consecrated her to God and to the order of Fontevrault. Joan died on September 24th 1199 in Rouen. She was 33 years old. After she died, her belly was opened and her child, a boy, was extracted. Baptised as Richard, her son lived only for a couple of hours and was later buried in Rouen’s Cathedral. (“[…]cette princesse ayant obtenu la grâce qu'elle avoit demandée avec tant d'instance, mourut- bientôt après, le 24 de septembre de l'an 1199, &, comme elle étoit avancée dans sa grossesse, on l'ouvrit dès qu'elle fut morte. On lui tira un enfant qui eut le temps de recevoir le baptême & qui, étant décédé presque aussitôt, fut inhumé dans l'église de Notre-Dame de Rouen.” in Histoire générale de Languedoc, p. 190). According to her wishes, she was buried in Fontevrault Abbey, at her father’s feet and next to her brother Richard. She would be later joined by her mother (1205), buried next to Henry II, and her son Raymond (1249), buried next to her (“Quant au corps de la comtesse, la prieure de Fontevrault l'apporta avec elle dans cette abbaye, où il fut inhumé aux pieds du roi Henri H, père de cette princesse, & à côté du roi Richard, son frère.” in Histoire générale de Languedoc, p. 190). In her will, she presents herself as “queen Joan of Sicily”, leaving aside the humbler title of Countess of Toulouse. Admist the generous distribution of bequests among her servants, many churches and the main beneficiary, the Abbey of Fontevrault, Joan assigned an annual payment of 20 marcs to the Abbey to commemorate “the anniversary of the king of Sicily and herself”.

Her husband Raymond would marry two more times, with the Damsel of Cyprus, and after divorcing her, with Leonor of Aragon. He would be succeeded in 1222 by his and Joan’s son, Raymond VII.

Sources

- Annales Monastici, Annales de Burton

- Annales Monastici: Annales monasterii de Wintonia, A.D. 519-1277

- Bowie, Colette, To Have and to Have Not: The Dower of Joanna Plantagenet, Queen of Sicily (1177–1189), in Queenship in the Mediterranean. Negotiating the Role of the Queen in the Medieval and the Early Modern Eras

- Calendar of documents preserved in France, illustrative of the history of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol.1. A.D. 918-1206

- Chronicle of Richard of Devizes concerning the deeds of Richard the First, King of England

- Chronique de Maître Guillaume de Puylaurens sur la guerre des Albigeois (1202-1272)

- Chronique de Robert de Torigni, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel

- Delle Donne, Fulvio , GIOVANNA d'Inghilterra, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani

- Foedera, conventiones, literæ, et cujuscunque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliæ et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices, principes, vel communitates, ab ineunte sæculo duodecimo, viz. ab anno 1101

- Histoire genealogique de la Maison D’Auvergne

- Histoire générale de Languedoc

- Matthæi Parisiensis, monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica majora

- Wieruszowski, Helene , The Norman Kingdom of Sicily and the Crusades, in A History of the Crusades, vol. II, The Later Crusades, 1189-1311

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

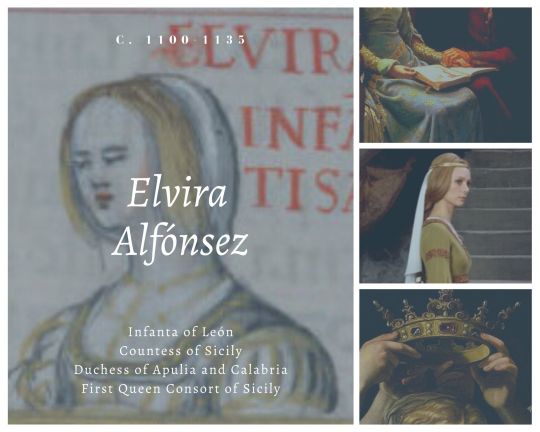

Factum est autem cum Rex Rogerius Siciliam repetisset,eodem anno, non multo post, corporis languore corripitur. Sed cum -Deo tribuente- citius convaluisset, Alberia regina coniunx ipsius, mox infirmitatis tacta incommodo, ad extrema pervenit; que videlicet mulier, dum vixit, religionis gratia atque elemosinarum largitione fertur plurimum enituisse. Qua defuncta Rex ipse ita meroris contritus est amaritudine ut multis se diebus intra cameram recludens, exceptis eius privatis obsecutoribus non apparuerit; unde accidit ut, fama paulatim diffusa, non solum hiis qui longe verum etiam qui prope erant, vere obisse existimaretur.

Alessandro of Telese, De rebus gestis Rogerii Siciliae regis

Elvira (also known as Albidia, Albiria, Geloira, Helbiria, Helviria) was born around 1100 in León as the daughter of Alfonso VI the Brave, King of the reunited León and Castile and of Galicia. Her mother was Alfonso’s fourth wife Isabella, a former Muslim princess called Zaida, and previously the widow of Abu al Fatah al Ma'mun, ruler of the Taifa of Córdoba.

As it’s not certain the exact date of her birth, the same goes for the date of her marriage to Ruggero II of Sicily, since it’s not recorded in any source. According to author Romualdo of Salerno, at the time of his marriage, Ruggero was young and still a count (”Hic autem, quum esset Comes, et juvenis, Albyriam filiam Regis Hispaniae, duxit uxorem, ex qua plures liberos habuit”). Since their first child, Ruggero (c.1118-1148), was born around 1117-18, the marriage must have been celebrated right before that year. After Ruggero, Elvira gave birth to Tancredi (c.1119-1138), Alfonso (c. 1120-1144), an unnamed daughter (- c. 1135), Guglielmo (c. 1120-1166) and Enrico (before 1135- 1113/45?) .

In 1127, Ruggero’s cousin Guglielmo of Apulia died without legitimate issue. As his heir, the Count of Sicily then claimed all the Hauteville possessions in Southern Sicily as well as the principality of Capua, alienating thus the Papacy as well as the local lords, who were opposed to the union of Apulia with Sicily. As a result, Honorius II excommunicated Ruggero and declared a crusade against him. After the Hauteville managed to militarily occupy the Duchy of Apulia, the Pope was forced to declare himself defeated and, in 1128, he officially bestowed Ruggero the title of Duke of Apulia, Calabria and Sicily. The year after Ruggero was also proclaimed Duke of Naples, Bari and Capua. In 1130 Honorius II died and his death gave rise to a schism as two cardinals were simultaneously elected. The Hauteville decided to support Anti-pope Anacletus II’s claims of supremacy over Pope Innocent II. To thank him for his support, Anacletus proclaimed Ruggero King of Sicily. On Christmas Day 1130, Ruggero and Elvira were crowned King and Queen of Sicily in Palermo’s Cathedral.

Almost nothing is known about Elvira’s personal life, despite her role of first Queen Consort of Sicily. In his De rebus gestis Rogerii Siciliae regis, abbot and historian Alessandro of Telese merely wrote that, while being still alive, she was renowned for her faith and her charities (“que videlicet mulier, dum vixit, religionis gratia atque elemosinarum largitione fertur plurimum enituisse”).

A strong bond of affection and mutual respect must have certainly existed between Ruggero and Elvira as it is shown on the occasion of the Queen’s death. Both spouses fell ill by the end of 1134, but while Ruggero recovered, Elvira died on February 6th.

The King was so heartbroken and distraught from grief, he confined himself in his chambers for many days, allowing only his close attendants in ( Qua defuncta Rex ipse ita meroris contritus est amaritudine ut multis se diebus intra cameram recludens, exceptis eius privatis obsecutoribus non apparuerit ). The sudden disappearance of Ruggero gave soon rise to the rumor he too was dead. Despite having submitted to Ruggero five years prior, Roberto of Capua took advantage of the (fake) news and, from his shelter in Pisa, he planned to occupy the Principality of Capua, which by hereditary right belonged to him. Ruggero was then forced to cut short his grieving period to stop this invasion. After again offering Roberto the chance to (nominally) keep his title in exchange for his submission, the King offered the title of Prince of Capua to his son Alfonso instead.

The Queen was buried in the chapel of St. Mary Magdalene, in Palermo. She had personally ordered for the chapel to be built with the desire to be buried there and make the chapel the official burial site for the royal family (after the Cathedral’s renovation works ended in 1185, all of the mortal remains previously inhumed in St. Mary Magdalene were moved there, except for those of Elvira and her children’s, which were left in the original site).

Ruggero’s mourning for his beloved wife lasted for an incredible long period. For the next 14 years he would refuse to remarry. It would be only when, one by one, all his sons died and only Guglielmo was left, that Ruggero realised his lineage was in danger. In 1149 he married to Sibylle of Bourgogne, who will give birth to a boy Enrico, who will die young, and a stillborn baby [“Nam primo Albyria illustris Regina uxor ejus, ex qua tres filios habuerat, mortua est, et filia ejus. Post haec Tarentinus Princeps, et Anfusus Capuanorum, et Henricus mortui sunt. Novissime autem Rogerus Dux Apuliae, primogenitus ejus, mortus est Anno Domini ac Incarnationis MCXLIV, Ind. XII, vir quidem speciosus, et miles strenuus, pius, benignus, misericors, et a suo populo multum dilectus […] Et quia solum Guilielmum Capuanorum Principem habebat superstitem, veritas ne eudem conditione humanae fragilitatis amitteret, Sibilia sororem Ducis Burgundiae duxit uxorem […]”). This would prove to be a very short union as Sibylle died shortly after of complications related to childbirth. In 1151 Ruggero married for a third and last time. The chosen wife was Beatrice of Rethel, who would bore him the future Queen Costanza I, although Ruggero never saw his daughter since he died on February 26th 1154, and Costanza would be born almost nine months later, on November 2nd.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The Norman monarchs tended to choose their wives not from among the families of powerful Sicilians. Rather, they married women from prominent European courts.

Thus, their wives might be presumed to have brought a European influence to the cultural life of the kingdom. However—despite the fact that a number of the Norman queens ruled as regents for their underage sons; despite evidence that some of the queens had the capacity to influence Sicilian culture and even exerted a certain amount of effort to this end—this does not seem to have been the case.

The Norman queens (like their husbands) were often larger than life characters, whose extraordinary biographies reflect the turbulent times in which they lived. Roger II married a woman by the name of Elvira, daughter of a Spanish king (Alfonso VI, king of Castile and León) and his Moorish wife (Zaida, who took the Christian name Isabella when she married Alfonso). The marriage seems to have been a sentimental as well as a dynastic success. Elvira bore Roger five sons, including the next king of Sicily, William I, before she died in 1135, at the age of about thirty five. A medieval historian reports that following Elvira’s death, Roger was “so saddened by the bitterness of mourning that he closed himself for many days in his room, and did not appear except to his private staff; and so it happened that a rumor gradually spread, not only to those who were far away but even to those in the immediate proximity, that Roger had died.” Roger was obliged to put down an attempted coup when an ambitious Sicilian count sought to take advantage of the power vacuum resulting from the king’s withdrawal from the public eye.

Although Elvira had given Roger five sons, only one of them—the sickly, unpromising William—reached maturity. Fifteen years after Elvira’s death, Roger was obliged to marry again in order to ensure succession. Again, his long celibacy was quite extraordinary. Even with a plurality of potential heirs, a medieval king was likely to remarry following the death of a wife, both because marriage presented an opportunity to forge political alliances and because a consort came in handy at state ceremonies. Roger’s reluctance to remarry seems to provide further evidence of his affection for Elvira.

But William, against the odds, survived his father and was crowned king of Sicily following Roger’s death. In about the year 1150, he married Margaret of Navarre, daughter of King Garcia IV Ramirez of Navarre and Margaret de l’Aigle. The biography of William’s consort demonstrates what would become a truism of the Norman queens: they attracted attention, in general, only when their actions offended public opinion. Following her husband’s death, while Margaret ruled as regent for her son, the second William, she summoned a party of Frenchmen to Sicily (including Peter of Blois, who acted as tutor to young William). The Sicilians were not pleased at the influx of foreigners; nor did the French seem inclined to lengthen their stay in Sicily, although Margaret insisted and ultimately prevailed on this point. With Margaret’s support, one of the Frenchmen—Stephen, son of the count of Perche—was made chancellor and archbishop-elect of Palermo. This action earned her the enmity of the Sicilians, who resented the power given to a “puerum alienigenam” (a foreign-born boy) and suspected that less than professional sentiments motivated the queen’s actions. It was said that “the queen, although she was Spanish, called this French boy her brother, spoke to him too familiarly, and looked at him with hungry eyes; they feared that under the cover of professional proximity, an illicit love was hidden.” But Margaret’s efforts to staff her court with Europeans proved unfruitful. Peter of Blois soon left Sicily and described the island afterward as a hazard to travelers by virtue of both its climate and its people (“Sicily is to be faulted because of its air, and it is to be faulted for the malice of those who live there; I consider it hateful and almost uninhabitable”). Stephen’s (and Margaret’s) political enemies would drive Stephen himself out of Sicily in 1168.

So, too, a late Norman consort—Sibilla, wife of Tancredi of Lecce, an illegitimate grandson of Roger II who vied for control of Sicily following the death of William II in 1189—drew the enmity of her contemporaries by virtue of her political machinations. We possess a wholly unsympathetic account of Sibilla in the history written by Peter of Eboli. Peter, a partisan of Sibilla and Tancredi’s rivals for the Sicilian throne, Norman Constance and Hohenstaufen Henry VI, details an intrigue that pitted Sibilla against Constance. In the opening chapter of this unsavory history (which, in honesty, seems to consist of equal parts polemic and factual account), Tancredi asks Sibilla to invite Constance to Palermo. In her reply to him, Sibilla accuses him of raving senselessly; to honor Constance with her company, Sibilla believes, would implicitly acknowledge Constance’s authority. In the end, Constance, rather than being received as an honored guest, was imprisoned by Tancredi and Sibilla. But the ruse did not last long. The pope interceded and Constance was released to the keeping of her husband. Following Henry’s elevation to the Sicilian throne, Sibilla would repent and seek forgiveness for her scheming; she, along with her daughter, would end her life in an Alsatian convent.

The machinations of that Constance against whom Sibilla plotted, of course, would have a more appreciable effect on history. And historians would repay Constance in kind, making her (like the kings of Sicily) the protagonist of fantastic tales. Constance, daughter of Roger II, had been consigned to a convent, from which she was summoned to marry her Hohenstaufen husband in order to grant dynastic support to his Sicilian ambitions. She had already reached an advanced age, by medieval standards, when she was married and had passed her fortieth birthday when she bore her first and only child, Frederick II. The fourteenth-century historian Villani reports that Frederick’s birth challenged belief on two counts: because he was born to a woman consecrated to God, and because of his mother’s age (which he exaggerates, giving her more than fifty two years when she gave birth). The Sicilians, Villani says, frankly doubted Constance’s capacity to bear a child at her age; “for which reason, when the time came for her to give birth, she had a tent pitched in the center of Palermo, and made an announcement that any woman who wished might come to see her. And many came and saw, and so the suspicions ceased.” Giovanni Boccaccio, in his biographical dictionary of famous women, exaggerates both Constance’s age—he calls her a “wrinkled old woman”—and the prophetic significance of her pregnancy and Frederick’s birth. He attributes to Constance’s son the responsibility for the eventual fall of the Kingdom of Sicily. And after detailing his (rather fantastic) version of Constance’s late marriage and pregnancy, he asks: “Who will not judge Constance’s conception and childbirth to be monstrous?” In truth, Constance’s actions were characterized by less supernatural portent and more pragmatic significance. Following Frederick’s birth (in 1194, and in Iesi, not Palermo) and Henry’s death (in 1197), Constance ignored her husband’s wishes that a German ally be made Frederick’s regent. She sent the Germans out of Sicily, named the pope regent to her son, and had the four-year-old prince crowned king of Sicily in Palermo, before her own death in 1198.

History might remember the name of the Sicilian queen, particularly when she—like Margaret of Navarre or Constance, or like Adelaide, Roger II’s mother—acted as her son’s regent following her husband’s death. But the queens seem to have had little appreciable impact on the cultural life of the kingdom. The Norman kings tended to marry women from European (typically French or Spanish) courts, like the consorts mentioned above—with the exceptions of Sibilla, wife of the illegitimate and luckless Tancredi, and Constance, wife of the scion of a German house, both of whom were Sicilians. William II married Joanna Plantagenet, daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine, a name that looms large in the history of European literature. But even this match seems to have done little to promote Romance letters in Sicily. Rather, the Norman monarchs seem to have pursued a diametrically opposed literary policy: they solicited the production of poetry in Arabic.”

Karla Mallette, The Kingdom of Sicily, 1100-1250. A Literary History, p. 93-97.

#queens of sicily#countesses of sicily#queens of jerusalem#countesses of toulouse#Holy Roman Empresses#queens of germany#sicily

137 notes

·

View notes

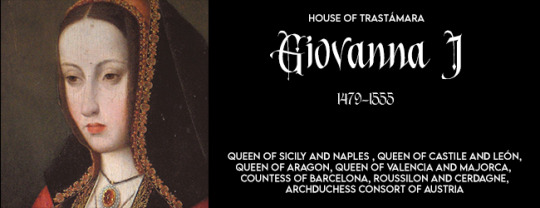

Photo

#queens of sicily#Holy Roman Empresses#queens of germany#queens of aragon#queens of naples#queens of castile#queens of leon#sicily

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

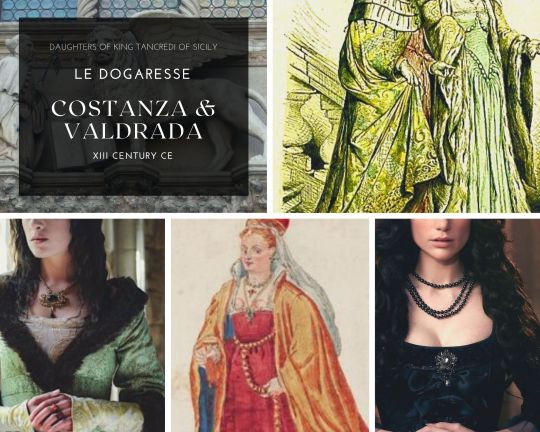

The qualifications for the Dogado were : ( i ) Ripe age ; (2) Urbane temperament ; (3) Good birth ; and (4) Ample private means. One man, and one man alone, stood out head-and-shoulders above his peers, as possessed of these four qualities, a man whose thirty years of distinguished public service placed him in the unique position of first citizen of Venice. By universal acclamation Pietro Ziani was chosen to wear the laurel -wreathed berretta of the great Dandolo. The son of one of the most distinguished of the Doges — Sebastiano Ziani — he had borne himself nobly as a successful naval commander, a tactful ambassador, and an upright magistrate. Handsome above the ordinary, pious without hypocrisy, talented in linguistic and forensic aptitude, and passionately loyal to the Constitution, he was calmly awaiting his destiny at his country residence at Arbe in Dalmatia.

A deputation of the Lords of the Council boarded the magnificent “ Bucintoro” and accompanied by thirty galleys, all splendidly decorated with rare brocades and tapestries, set off to meet and escort the new Doge. Pietro Ziani’s progress was a triumphal procession, calling to mind the unanimous and felicitous election of Domenigo Selvo one hundred and fifty years before. Almost the first act of the new regime was the affirmation of the cordial relations which his father, Sebastiano, had entered into with Guglielmo II. — “The Good,” King of Sicily. Dante refers to the death of this distinguished Sovereign in Canto XX of the Paradiso :

—" William whom the land bewails

So well beloved in Heaven.“

In confirmation of the new treaty the new Doge; in 1213, sought and gained the hand of the Princess Costanza, daughter of King Tancredo, Guglielmo’s son and successor. She was the first Norman Dogaressa of Venice, daughter of a brave and ardent race, a woman of conspicuous ability and ambition, and an ideal consort for the Head of a rejuvenated Venice.

Pietro Ziani had but lately buried his first wife, the modest and beautiful Countess Maria Baseggio — whose father held the high office of Procurator of San Marco — nobilis et decora nimis Maria Dukessa— as she is called in the Altino Chronicle. The sole offspring of this union was a son, Giorgio, but, alas, when yet a child, he was torn to pieces by the savage mastiff watch-dogs of the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore. It was said that the Doge was so infuriated by this misfortune that he ordered the church and monastery with all the animals, — the poor monks as well, — to be consumed with fire : one may hope the innocent Religious escaped the fury. Anyhow the rest were all burnt, and then the remorse of Ziani was pitiable. By way of reparation he set to work at once to rebuild and re-endow what he had so petulantly sacrificed.

Dogaressa Costanza was handsome and gracious, and wore her Royal honours with distinction. Palazzi wrote thus of her — "A Queen by birth, Dogaressa of Venice by marriage, she exhibited all the attributes of her royal station, — she was also Duchess of Calabria, — and her high breeding, no less than her beauty, raised her above all petty jealousies.” In the ancient pack of playing-cards, at the Venetian Museo Civico, we find her represented upon the “Ten of Spades,” with the following legend : — “ Costanza, daughter of Tancredo King of Naples, wife of Doge Pietro Ziani, was accustomed to meet all the malcontents against the Doge and herself with the saying : — ’ I have nothing to do with you ! ’ ”

The State being involved in tremendous financial difficulties on account of the cost of the Crusades, and also in behalf of the purchase of the island of Crete, in view of the Doge’s great private wealth, —'L’ haver Ziani’’ was quite as true of Pietro as of Sebastiano — reduced his official salary to 2800 lire, with 100 thrown in as a free gift. It was further decreed that all tributes to the Doge should henceforth be shared between him and the treasury of San Marco. Moreover he was required to make an offering of three silver trumpets for ceremonial processions, and to undertake the repairs of the Ducal Palace, — rather a one-sided bargain !

Fifteen years of marital happiness fell to the lot of the Doge and Dogaressa. Three children were borne by imperious Costanza — Marco, Marchesina, and Maria. Some authorities say that the Dogaressa died suddenly in 1228 and that the Doge, broken-hearted, followed her within a month. The Altino Chronicle however records the abdication of Pietro Ziani, and adds that he and his Consort, with their family, retired into private life and went to reside in their palace upon the fondamento of Santa Giustina, where he died, and then received sepulture in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, in the tomb of his

father Sebastiano.

There is still a third version of the deaths of Doge Pietro and Dogaressa Costanza. In the terrible earthquake of 1220, when the church and monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore were destroyed, and the islands of Amiano and Costanzina swallowed up, it was said that many people died of fright, and among them the Dogaressa. The Doge, sharing the universal sense of insecurity in Venice, proposed to move the seat of Government to Constantinople, but, upon the cessation of the seismic disturbances, wiser counsels prevailed, and he set to work to rebuild the shattered edifices. In 1229 Pietro Ziani exchanged the silk-brocaded robe of State for the worsted habit of a Benedictine, and ended his days in the new monastery of San Giorgio which he had built.[…]

The last years of Doge Pietro Ziani were embittered by the rivalries of the families of Tiepolo and Dandolo — partisans of both sides eagerly grasping the Ducal chair, and impatient of the demise of its occupant. The Doge and Dogaressa were so worried and oppressed by these unseemly contentions that he executed a deed of abdication, and returned to his private residence, leaving the distinguished but thankless office to be filled by another.

Giacomo Tiepolo represented the old ideas and Marino Dandolo the new, and the votes of the Council were equally divided ; but at last, a majority was found for the former. Tiepolo was out and away the most enlightened and intellectual man of his time. He came of an ancient family, one of the “Apostolic” order of nobility — “ Teupolo ” in the old spelling, and originally from Rome. Bartoldo Teupolo, the head of the family in 697, was one of the electors of Doge Paolo Lucio Anafesto. In 1 204, when so many Venetian nobles assumed territorial titles of sovereignty over islands in the Greek Archipelago consequent upon the fall of Constantinople, Giacomo Tiepolo was named Duke of Candia, His father was Lorenzo, Procurator of San Marco in 1207, and Podesta of Treviso.

“ Duke ” Tiepolo took to wife Maria Storlato — a Venetian gentlewoman of no high degree, but a good and faithful spouse and mother. She was received as Dogaressa the day of Giacomo’s election in 1228, but alas, she died in 1240, having given him three sons as pledges of her devotion — Pietro, Lorenzo, and Giovanni. The eldest became Count of Sant’ Agostino and Podesta of Milan and Treviso, but, being taken prisoner by the Emperor Frederic II., he was treacherously beheaded.

A two years’ widowerhood found the Doge once more at the feet of an attractive woman, not indeed a simple Venetian maiden but a Princess of Royal degree, — Valdrada, the daughter of King Tancredo of Sicily. The new Dogaressa, like her brother King Ruggero, was famed for good commonsense, and sound probity of life, and she assumed at once an unquestioned control over the actions of her Consort, strong man though he was. Like her sister, the Dowager Dogaressa Costanza, she was a virago, in the sense of a strong personality; and she followed in her sister’s steps, ruling not alone her husband, but bending to her will all with whom she was thrown in contact.

Perhaps the new Dogaressa’s ostentation of Regal rank in the Venetian Court was a decisive factor in the promulgation of what was called the “ Promissione ” — perhaps best translated by the French term, Protocol — of 1242, the provisions of which greatly restricted the power and liberty of the Doge and Dogaressa. The Doge was henceforth to be, not the executive Head of the State, but the executor of the orders of the Council. Acts of homage were no longer to be rendered to him, nor was he to be addressed as “ Domine Dominus.” In times gone by the deputation of nobles, commissioned to acquaint a new Doge of his election, were accustomed to greet him thus : — “ Welcome, Messer Doge, God give you Messer Doge a good morrow, we are come to dine with you, we await your orders, and we wish to kiss your hand.” The Dogaressa also shared the new restrictive conventions, and neither relatives of hers, nor of the Doge, were eligible for any public office. Their household was limited — only twenty-five free retainers were allowed and a like number of unpaid dependent slaves. […]

Doge Giacomo Tiepolo’s time was much occupied with the settlement of internal jealousies and factions, and by the conduct of naval and military expeditions. While he was so employed Dogaressa Valdrada gave her whole time to the patronage and support of the Trade Corporations — a role maintained by all her successors.

At length, in 1209, the Doge, wearied alike by the exertions of his foreign enterprises and by the keenness of political rivalries at home, executed a deed of abdication, and, with Dogaressa Valdrada and her two young children retired to his private residence at Sant’ Agostino, in the sestiere of San Polo or Paolo. He did not long survive his retirement from office, and both he and his Consort, who outlived him three years, were buried in SS. Giovanni e Paolo. In every sense of the word Giacomo Tiepolo — “ The Legislator ” — was a “ Grand ” Doge — the sixth upon whom that title may be properly bestowed.

Staley, Edgcumbe, The dogaressas of Venice : The wives of the doges, p. 88-99

23 notes

·

View notes

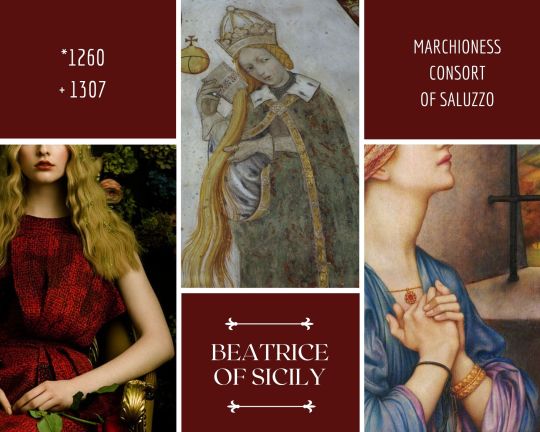

Text

- E lo princep respos al almirall: -Ques aço que vos volets que yo hi faça? que si fer yo puch , -volenters ho fare.- Yo , dix lalmirall , quem façats ades venir la filla del rey Manfre, germana de madona la regina Darago, que vos tenits en vostra preso aci el castell del Hou , ab aquelles dones e donzelles qui soes bi sien ; e quem façats lo castell e la vila Discle retre . - E lo princep respos , queu faria volenters. E tantost trames un seu cavaller en terra ab un leny armat, e amena madona la infanta , germana de madona la regina , ab quatre donzelles e dues dones viudes. E lalmirall reebe les ab gran goig e ab gran alegre , e ajenollas, e besa la ma a madona la infanta.

Ramon Muntaner, CRÓNICA CATALANA, p. 221

Beatrice was born (probably) in Palermo around 1260. She was the first child and only daughter of Manfredi I of Sicily and his second wife, the Epirote princess Helena Angelina Doukaina (“[…] et idem helenam despoti regis emathie filiam sibi matrimonialiter coppulavit, ex quibus nata fuit Beatrix.”, Bartholomaeus de Neocastro, Historia Sicula, in Giuseppe Del Re, Cronisti e Scrittori sincroni Napoletani editi ed inediti, p. 419). It’s quite plausible the baby had been named after Manfredi’s first wife, Beatrice of Savoy (mother of Costanza, who will later become Queen consort of Aragon and co-regnant of Sicily). The little princess would soon be followed by three brothers: Enrico, Federico and Enzo (also called Anselmo or Azzolino). With three sons, Manfredi must have thought his succession was secured.

Beatrice’s father was one Federico II of Sicily’s many illegitimate children, although born from his most beloved mistress (and possibly fourth and last wife), Bianca Lancia. Since his father’s death in 1250, Manfredi had governed the Kingdom of Sicily on behalf firstly of his (legitimate) half-brother Corrado and, after his death in 1254, of Corrado’s son, Corradino. In 1258, two years prior Beatrice’s birth, Manfredi had been crowned King of Sicily in Palermo’s Cathedral, de facto usurping his half-nephew’s rights.

Keep reading

45 notes

·

View notes

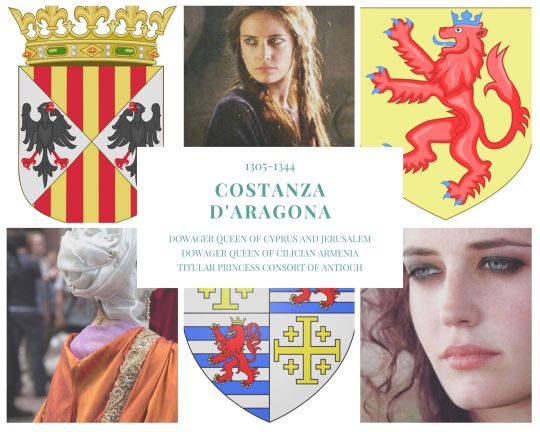

Photo

The day 4 October, day of the feast of St. Francis, Queen Costanza came to Famagusta. She was the daughter of King Federico of Sicily. She came with six galleys, who went to call Messer Bartholomio Montoliffo, bishop of Limassol, and two Friars Minor. This Queen Costanza came to Nicosia from Famagusta on 9 October, and she was married on Sunday the 16th of the same month in Nicosia, with great celebration and a court arranged for fifteen days. The day of the wedding she was anointed and crowned Queen, and she wore the crown with great honour.

Chroniques d’Amadi et de Strambaldi, t. 1, p. 398-9 [translation is mine]

Costanza was born in Sicily in 1305, the third child and first of the daughters of King Federico III of Sicily and his wife Eleonora of Naples.

At the tender age of one year old, she was betrothed to Prince Robert of France, youngest child of Philip IV of France and Queen Joana I of Navarre and Champagne. Robert, who was at that time 9, was a distant relation of his fiancée through her mother’s side. Unfortunately, the following year the young Robert died, resulting in the annulment of the betrothal.

Ten years later, in 1317, the 12 years old Costanza was married to Henri of Lusignan, 34 years her senior, King of Cyprus and Jerusalem. Henri was the son of Hugues of Cyprus (Hugues III) and Jerusalem (Hugues I), and of Isabelle of Ibelin. Henri had succeeded his brother Jean, who had reigned for just one year (1284-85), before dying suddenly. Jean’s death was so sudden, some authors speculated he had been poisoned by his brothers.

Costanza had reached Cyprus at the beginning of October, and the ceremony was held in St. Sophia Cathedral in Nicosia, on October 16th. The same day she was anointed and crowned Queen consort of Cyprus and Jerusalem.

The Cypriot marriage only lasted 7 years since Henri died on the night between March 30th and 31st while he was away on a hunting trip. As the union had been childless, Henri was succeeded by his nephew Hugues IV.

As she didn’t have any more reasons to stay in Cyprus, Costanza went back to Sicily, where (once again) she found herself involved in her father’s matrimonial politics. In the meantime, in Cilician Armenia, King Leo IV, known for his pro-western tendencies, had decided to pursue his project to unify the Armenian and the Roman Churches. After ordering the murder of his wife Alice (who was moreover his stepsister as the daughter of his stepfather and former Regent, Oshin of Korikos), the now widower asked Federico III for his daughter Costanza’s hand. Federico was too happy to oblige. Once again the Sicilian princess left her home to travel towards the east. She reached Cilicia and on December 29th, 1331, they got wed in Tarsus. Unfortunately for Leo, his rapprochement to a western and Roman Catholic power was heavily criticised by his subjects, resulting in his murder on August 28th, 1341, at the hands of his own barons. His marriage to Costanza proved fruitless, and his only child by Alice, Hethum, had died before 1331, so Leo was succeeded by his cousin Guy of Lusignan (who will adopt the name of Constantine).

The twice widowed Costanza again went back to Sicily, where her brother Pietro had in the meantime become King. Pietro died in 1342 and was succeeded by his 6 years old son, Ludovico (or Luigi), under the regency of his mother, Elisabetta, and his uncle, Giovanni. The following year, Costanza (almost 40 years old) was forced to marry a third and last time. Her third chosen husband was a 13 years old boy, Jean of Lusignan, Prince of Antioch and future Regent of Cyprus. Jean was son of Hugues IV and his wife Alix of Ibelin. Since he was related to Costanza’s first husband (he was Henri’s great-nephew.), they had needed a papal dispensation to marry. The marriage was celebrated on April 16th, 1343, but the union was short lived as Costanza died in Cyprus the following year (presumably on April 19th). Jean would remarry 6 years later with Alice of Ibelin, who would bear him his only child, Jacques.

Costanza fancasted as Eva Green

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ante omnia memorandum est quid de Anna Alamanna tentaverit. Fuerat haec exiguo tempore conjunx Joannis Augusti, patria Theodori Lascaris, ab eo ducta in extremo senio, Friderici Siciliae regis filia, Manfredi soror, quam a legatis ad eam accersendam missis deductam et solemni, coronationis ritu Augustam declaratam memoratus imperator Joannes uxorem, eamque percaram, habuerat.

Georgius Pachymeres, De Michaele Palaeologo, vol I, liber III, 7, 181