Text

I am sorry to everyone who tagged me in some tag game and I never responded. I saw it and thought “aww they thought of me” and proceeded to forget about it right after

49K notes

·

View notes

Photo

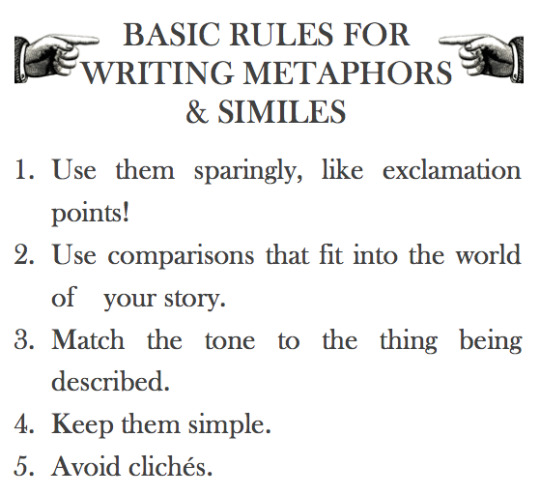

RULE #1: Use them sparingly.

Comparisons draw attention to themselves, like a single red tulip in a sea of yellow ones. They take the reader out of the scene for a moment, while you describe something that isn’t in it, like you’re pushing them out of the story. They require more thought than normal descriptions, as they ask the reader to think about the comparison, like an essay question in the middle of a multiple choice test. They make the image stand out, give it importance, a badge of honor of sorts.

Use too many comparisons and they become tedious.

Elevating every single description is like ending each sentence with an exclamation point. Eventually, the reader decides no one could possibly shout this much, and starts ignoring them.

For these reasons, you should only use metaphorical language when you really want to make an image stand out. Save them for important moments.

RULE #2: Use comparisons that fit into the world of your story.

If you’re writing from the point of view of a character who’s only ever lived in a desert, having that character say, “her look was as cold as snow” doesn’t make much sense. That character isn’t likely to have experienced snow, so it wouldn’t be a reference point to them. They’d be more likely to compare the look to a “moonless desert night” or something along those lines.

Using a comparison that ties to the character’s history or the setting of the story also do work to build the world of the story. It gives you a chance to show the reader exactly what your character’s reference points are, and builds the story’s world. If your reader doesn’t know that desert nights can get cold, this comparison informs both the things its describing: the other character’s look and the desert at night.

Here’s a metaphor from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

If you took a couple of David Bowies and stuck one of the David Bowies on the top of the other David Bowie, then attached another David Bowie to the end of each of the arms of the upper of the first two David Bowies and wrapped the whole business up in a dirty beach robe you would then have something which didn’t exactly look like John Watson, but which those who knew him would find hauntingly familiar.

He was tall and he was gangled.

This is a bizarre comparison, but it’s also a bizarre story. What’s more, David Bowie is known for his persona “Ziggy Stardust” and songs like “Space Oddity.” Bringing him up in a book about a man from Earth traversing the galaxy makes sense. What’s more it increases both of those aspects of the story: its ties to space and its bizarre-ness. The comparison unifies the story and the language being used to tell the story.

Using comparisons that fit into the world ensures that everything is working to help tell the story you want to tell.

RULE #3: Match the tone to the thing being described.

Or, match it to the way you want the thing being described to come across. It has to match what you want the reader to feel about the thing being described.

Here’s an example from Mental Floss’s “18 Metaphors & Analogies Found in Actual Student Papers” (although I think it’s actually from a bad metaphor writing contest):

She had a deep, throaty, genuine laugh, like that sound a dog makes just

before it throws up.

You’re not imagining a laugh right now, are you? You’re imagining a dog throwing up. Whoever this girl is, you’re going to make sure never to tell a joke in front of her.

This is not getting the right point across.

Remember the David Bowies? Remember how the comparison was fun and bizarre, just like the tone of the book is fun and bizarre?

This is not David Bowies stacked on top of one another.

It’s not enough for a comparison to be accurate. It has to bring about the same emotions as the thing it’s describing.

If this is being told from the point of view of a character who hates the laughing character and we’re supposed to hate her and her laugh. It actually does work, but from the use of the word “genuine,” I don’t think this is the case.

Make sure you always pay attention to the tone of the comparison.

RULE #4: Keep them simple.

Don’t use a comparison that requires too much thought on the reader’s part. You never want anyone sparing even a moment on the question: “but how is x like y?”

Here’s another example from that Mental Floss list:

Long separated by cruel fate, the star-crossed lovers raced across the

grassy field toward each other like two freight trains, one having left

Cleveland at 6:36 p.m. traveling at 55 mph, the other from Topeka at

4:19 p.m. at a speed of 35 mph.

Again, this is a humorous example. It’s supposed to be bad, but many writers have made mistakes like it. They choose two images that don’t have enough in common for the reader to make an easy and obvious comparison between the two. Sometimes, the writer subconsciously acknowledges this, and expands the comparison to a paragraph, detailing the ways the two things are alike.

If you find yourself doing this, take a step back and ask yourself if this is really the best comparison to be using. The best comparisons are the simple ones. All the world’s a stage. Conscience is a man’s compass. Books are the mirrors of the soul.

What about that David Bowie quote, you ask? Douglas Adams broke this rule, but he broke it purposefully to get that bizarre quality to the language. He still avoids reader confusion, the reason for this rule, by bringing the comparison back to its point at the end: “he was tall and he was gangled.”

RULE #5: Avoid cliches.

The best comparisons are fresh ones. No one wants to hear that she had “skin as white as snow” and lips “as red as roses” anymore. The slight understanding it brings to the description isn’t worth the reader’s groans when they realize you just made them read that again.

A cliche is a waste of space on the page. It’s not going to be the memorable line you want it to be. It’s not going to awe the reader.

Good similes in metaphors require some creative thinking.

In the vein of rosy lips and snow-colored skin, here’s a fun example from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. It’s the poem that Ginny wrote for Harry on Valentine’s Day:

His eyes are as green as a fresh pickled toad,

His hair is as dark as a blackboard.

I wish he was mine, he’s really divine,

The hero who conquered the Dark Lord.

These aren’t comparisons you’re like to have come across before and their originality comes from rules #2 and #3. Rowling needed comparisons that fit in Ginny’s frame of reference. She also needed comparisons that were humorously bad, as they’re being recited by a grumpy creature dressed in a diaper, who is sitting on Harry’s ankles, forcing him to listen.

As a witch at school, blackboards and fresh pickled toads fit Ginny’s frame of reference. Neither are particularly known for being nice to look at, so they fit the tone, too.

Using her character, setting, and tone, using, in other words, her story, Rowling was able to create similes that are unique and memorable.

It’s the same thing Adams did with his Bowie analogy.

If you, too, use your story to inform your language, writing new and wonderful similes and metaphors should be just as simple.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

My Revision Plan

I’ve been posting a lot about finishing a first draft of something new. So I thought it might be helpful if I also included my plans about what to do next.

Step One: Preserve the Draft

I work in Scrivener, so my first step is to compile, save, and preserve my draft. For me, this means I’m:

Capturing a snapshot of the current version of my chapters in Scrivener, so I can keep editing the main ‘manuscript’ files without losing access to the current version.

Exporting and saving the entire manuscript as “[TITLE] - First Draft - July 2020″ so that as I finish further revisions, I’ll always know which version this one is.

Emailing the draft to myself, saving it in iCloud, and printing it. Whatever it takes to ensure its safe keeping. This way, no matter what happens–if my computer falls into a pool and is destroyed–my entire first draft of this book will be safe somewhere.

This way, I can revise and edit and generally make a mess of things again without having to worry that anything I do going forward is going to affect the contents or completeness of my first draft.

Step Two: Second Sketches

I don’t want to dive into the editing process just yet, so before doing a serious re-read or re-plotting my entire book, I’m going to set about re-sketching my settings and characters.

In my first drafts, I treated my settings and characters as flexible. When I realized something about them wasn’t working, I changed that thing and kept going. Events changed locations, buildings changed distance from one another, Three of my characters had abrupt job changes in chapter ten, when I realized I could remove an extraneous plot and weave their storylines into a more central plot by doing so. Somewhere immediately after I tell the reader my protagonist has glasses, I forgot to ever mention them again.

This means my initial character and setting sketches are all–well, not useless, but not quite useful anymore either. Now that I’ve figured out where and what things and people need to be in order to make the story work, I’m writing down new “character/setting rules” to guide me through my first revision. I want to make them consistent.

For settings, this means I’m going to go through and decide on:

A “map” of the locations of the story and figure out exactly where things are in relation to one another

The layouts of individual settings

What specific places look, smell, and sound like

The “rules” of the world

For characters, this means I’m going to go through and decide on their:

physical characteristics

personality and backstory

relationships both with other characters and the world around them

character arcs: their wants, their fears, their internal conflicts, and how they’re supposed to be growing and changing throughout the novel

And if I decide my protagonist does wear glasses, I’m going to make sure she’s wearing them throughout the entire story.

Step Three: Read

Writing Advice

In the next few weeks, I’m going to read and reread books and blogs on writing. I am going to soak it all up. I’m going to learn or remind myself about what makes a story good. Refine my knowledge of writing craft. These are the ideas that are going to help me make my revised draft better than my first one.

Fun books!

I’m also going to read for fun, especially the books I was avoiding because they were in a similar genre/category to the one I was drafting. I want to know how good the “competition” is, and also see those “writing rules” I’ve been reading about in writing advice books/blogs in action.

The First Draft

Finally, I’m going to crack open my own book.

This is the hardest part of a revision: critically reading what I’ve written so I can prepare to tear it to pieces and rebuild it.

Oof.

For this, I recommend changing the font, either printing it out or putting it on an e-reader, settling down in your favorite spot to read, and reading it in one go. I’m probably going to print mine out and put it in a binder. This will help me see it with the eye of a reader/editor instead of an author, and hopefully help me put some emotional distance between me and the work I’ve done.

I’m going to keep a notebook nearby and take notes about things that are working, things that aren’t working, ideas for changes, and other stray observations (like words I’m using too often, or where I’m repeating myself, or abandoned plot points, etc.).

Step Four: Re-Outline

This step itself has many steps.

Step One: Identify the core idea of the story. In clear terms, write out in one or two sentences what this story is about, English-major style. ie. “This story is about a girl finding the courage to pursue the life she wants, not the one her parents have planned for her. Her struggles are reflected back on her when she encounters the ghost of a princess who cares so much what history thinks of her, she’s letting its opinion turn her into a literal monster.”

Step Two: Outline the events in the story as it currently exists.

Step Three: Evaluate how well it conveys the core idea, and how the current structure works. Identify:

the purpose of various scenes (ie. inciting incident)

Extraneous scenes/plots/characters

Plot points that should be in the story but are missing

Key moments of character arcs

Events that support the core idea

Events that either don’t support or work in opposition to the core idea

Step Four: Rebuild the outline so that the story has a strong structure that supports the core idea.

Step Five: Share

I know I’m going to struggle with figuring out exactly how to rebuild my story, so I’m going to share both my first draft and my unfinished plan with my writing friends. I’m going to ask them for their ideas and advice. With their feedback, I’m going to solidify my plan for my new outline, hopefully a bit more confident that it’s the right one.

I know not all people have a group of writing buddies they can easily do this with. If you don’t have a critique group, don’t sweat it. It helps and it’s worth an attempt to try to find one, but it’s not a vital step.

Step Six: Revise

Finally, I’m going to go through my work chapter by chapter: editing scenes, trashing scenes, and writing new scenes entirely from scratch until I have a manuscript that’s hopefully much better than the first.

If I revise this book like I did my last one, I’ll probably polish the chapters as I move through them, so that when i’m done, some chapters will be on their twelfth drafts, some will be on their second, but overall it’ll be the best version of the story I’m currently able to write.

–

It’s a lot, and it seems like a very daunting process from my current standpoint, but finishing the first draft seemed daunting too, just a few weeks ago, and I got through that process. With time and effort, I’ll get through this one too.

886 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Revision Plan

I’ve been posting a lot about finishing a first draft of something new. So I thought it might be helpful if I also included my plans about what to do next.

Step One: Preserve the Draft

I work in Scrivener, so my first step is to compile, save, and preserve my draft. For me, this means I’m:

Capturing a snapshot of the current version of my chapters in Scrivener, so I can keep editing the main ‘manuscript’ files without losing access to the current version.

Exporting and saving the entire manuscript as “[TITLE] - First Draft - July 2020″ so that as I finish further revisions, I’ll always know which version this one is.

Emailing the draft to myself, saving it in iCloud, and printing it. Whatever it takes to ensure its safe keeping. This way, no matter what happens–if my computer falls into a pool and is destroyed–my entire first draft of this book will be safe somewhere.

This way, I can revise and edit and generally make a mess of things again without having to worry that anything I do going forward is going to affect the contents or completeness of my first draft.

Step Two: Second Sketches

I don’t want to dive into the editing process just yet, so before doing a serious re-read or re-plotting my entire book, I’m going to set about re-sketching my settings and characters.

In my first drafts, I treated my settings and characters as flexible. When I realized something about them wasn’t working, I changed that thing and kept going. Events changed locations, buildings changed distance from one another, Three of my characters had abrupt job changes in chapter ten, when I realized I could remove an extraneous plot and weave their storylines into a more central plot by doing so. Somewhere immediately after I tell the reader my protagonist has glasses, I forgot to ever mention them again.

This means my initial character and setting sketches are all–well, not useless, but not quite useful anymore either. Now that I’ve figured out where and what things and people need to be in order to make the story work, I’m writing down new “character/setting rules” to guide me through my first revision. I want to make them consistent.

For settings, this means I’m going to go through and decide on:

A “map” of the locations of the story and figure out exactly where things are in relation to one another

The layouts of individual settings

What specific places look, smell, and sound like

The “rules” of the world

For characters, this means I’m going to go through and decide on their:

physical characteristics

personality and backstory

relationships both with other characters and the world around them

character arcs: their wants, their fears, their internal conflicts, and how they’re supposed to be growing and changing throughout the novel

And if I decide my protagonist does wear glasses, I’m going to make sure she’s wearing them throughout the entire story.

Step Three: Read

Writing Advice

In the next few weeks, I’m going to read and reread books and blogs on writing. I am going to soak it all up. I’m going to learn or remind myself about what makes a story good. Refine my knowledge of writing craft. These are the ideas that are going to help me make my revised draft better than my first one.

Fun books!

I’m also going to read for fun, especially the books I was avoiding because they were in a similar genre/category to the one I was drafting. I want to know how good the “competition” is, and also see those “writing rules” I’ve been reading about in writing advice books/blogs in action.

The First Draft

Finally, I’m going to crack open my own book.

This is the hardest part of a revision: critically reading what I’ve written so I can prepare to tear it to pieces and rebuild it.

Oof.

For this, I recommend changing the font, either printing it out or putting it on an e-reader, settling down in your favorite spot to read, and reading it in one go. I’m probably going to print mine out and put it in a binder. This will help me see it with the eye of a reader/editor instead of an author, and hopefully help me put some emotional distance between me and the work I’ve done.

I’m going to keep a notebook nearby and take notes about things that are working, things that aren’t working, ideas for changes, and other stray observations (like words I’m using too often, or where I’m repeating myself, or abandoned plot points, etc.).

Step Four: Re-Outline

This step itself has many steps.

Step One: Identify the core idea of the story. In clear terms, write out in one or two sentences what this story is about, English-major style. ie. “This story is about a girl finding the courage to pursue the life she wants, not the one her parents have planned for her. Her struggles are reflected back on her when she encounters the ghost of a princess who cares so much what history thinks of her, she’s letting its opinion turn her into a literal monster.”

Step Two: Outline the events in the story as it currently exists.

Step Three: Evaluate how well it conveys the core idea, and how the current structure works. Identify:

the purpose of various scenes (ie. inciting incident)

Extraneous scenes/plots/characters

Plot points that should be in the story but are missing

Key moments of character arcs

Events that support the core idea

Events that either don’t support or work in opposition to the core idea

Step Four: Rebuild the outline so that the story has a strong structure that supports the core idea.

Step Five: Share

I know I’m going to struggle with figuring out exactly how to rebuild my story, so I’m going to share both my first draft and my unfinished plan with my writing friends. I’m going to ask them for their ideas and advice. With their feedback, I’m going to solidify my plan for my new outline, hopefully a bit more confident that it’s the right one.

I know not all people have a group of writing buddies they can easily do this with. If you don’t have a critique group, don’t sweat it. It helps and it’s worth an attempt to try to find one, but it’s not a vital step.

Step Six: Revise

Finally, I’m going to go through my work chapter by chapter: editing scenes, trashing scenes, and writing new scenes entirely from scratch until I have a manuscript that’s hopefully much better than the first.

If I revise this book like I did my last one, I’ll probably polish the chapters as I move through them, so that when i’m done, some chapters will be on their twelfth drafts, some will be on their second, but overall it’ll be the best version of the story I’m currently able to write.

–

It’s a lot, and it seems like a very daunting process from my current standpoint, but finishing the first draft seemed daunting too, just a few weeks ago, and I got through that process. With time and effort, I’ll get through this one too.

886 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drafting

The Draft Notebook

Be More Productive with Ambient Noise

How to Steal: Know Your Tropes

How to Steal: Good Writers Borrow

Write What You Know (Not What You’ve Experienced)

The Best Way to End a Writing Session

How To Finish a Draft

A Few Tips on Chapters

Language, Description, & Dialog

“To Be” Or Not “To Be”: What Exactly Is Passive Voice?

Tagging Dialog

Narrative Voice

Writing Better Descriptions

Basic Rules for Metaphors and Similes

Character, Plot, & Setting

Creating Characters: a 4-Step Process

Writing Relationships Your Reader Can Get Behind

Informative Character Names

The Strength of a Symmetrical Plot

How to Foreshadow

Crafting Homes of Paper, Ink, and Neutral PH Glue

Motivation

On Writing Flawed Books

How to Return to Your Manuscript

The Acknowledgements Page

Staring at Blank Pages

What to Do When You Can’t Write

Motivational Writing Posters

Publishing

Writing the Perfect Query Letter

How to Write a Synopsis

How to Pitch Your Novel in Under a Minute

A Glossary of Publishing Terms: Vol 1

Writing Tools

Why You Should Give Scrivener a Try

Outlining, Brainstorming, and Researching with Scrivener

Drafting with Scrivener

Editing with Scrivener

CTRL+F

The Forest Productivity App

Editsaurus

NaNoWriMo

Why Try NaNoWriMo

October Prep

Why Listen to Writing Podcasts

Pick a New Daily Word Count Goal

How to Write 2000 Words a Day

How to Plan a Novel without a Story

Pacemaker: Custom Daily Word Count Website

NaNoWriMo Master Post

Other

How to Read an Absurd Number of Books

Writing Workshops: An Introduction

Writing Groups

Different Types of Fantasy Novels

Ambient Soundscapes Based on Famous Writers

Ko-Fi & Other Support

If you enjoy my posts and can afford it, I would greatly appreciate it if you donated to my new ko-fi page! Each of these posts represents multiple hours of unpaid labor. I love writing for this blog, but I’m also an underpaid 20-something trying to stay afloat. I’ve made this master post of every essay I’ve written for this blog as a way to show my appreciation in advance of any support. If you donate, to further show my gratitude and appreciation, I’ll take requests for essay topics in the ‘messages of support.’

If you can’t afford to donate via ko-fi, another great way to show your support is simply by reblogging posts that you find useful and helping my blog reach new writers.

Thanks so much!

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Crafting Homes of Paper, Ink, and Neutral PH Glue: Writing a Setting Your Reader Can Call Home

nb: this is the Sparknotes version of an essay I wrote for my MA last term.

Why do we love Hogwarts so much?

How can we strive to recreate the devotion readers have felt towards Hogwarts in our own writing?

These are the questions I asked myself last fall. I wanted to demystify the success of Hogwarts as a setting readers all over the world identify as a second home. To begin, I looked at a wide variety of fantasy books for similarities in settings I knew to be beloved: Hogwarts, Camp Half-Blood, The Shire, etc. (note: I had to narrow the field, and I found fantasy better at creating remarkable settings than contemporary fiction, with more well-known examples to draw from, but I would argue that the same principles apply to settings in contemporary fiction).

In my research, I identified six key elements for creating a setting that is sure to captivate readers.

THE HAGRID

The Hagrid is my own term for a maternal character who introduces the protagonist (and the reader) to the setting. The Hagrid is kind, nurturing, and, above all, very enthusiastic about the setting. Once the Hagrid has both the protagonist and reader excited about the setting, the Hagrid delivers the protagonist to the setting.

The Hagrid usually isn’t the mentor figure of the series, but can act as one before the mentor arrives. (Think Obi Wan versus Yoda)

Examples: Hagrid in Harry Potter, Grover in the Percy Jackson series, Obi Wan in Star Wars

Why might a writer want to include a Hagrid in their work? The Hagrid is useful for two things: building up the setting for the reader and letting us know that it is a place where we might find more friendly faces. The character is a subtle way of ensuring the reader trusts that this setting will be a good one.

A REMARKABLE POINT OF ENTRY

Narnia has The Wardrobe. Hogwarts has Platform 9 ¾. Camp Half-Blood has a magical barrier.

The remarkable point of entry separates the setting from the real world. It delineates the humdrum world the protagonist and reader are used to from the fantastical place they’re headed. It’s the harbinger of adventures to come.

Additionally, It lets both the protagonist and the reader in on a secret. Not just anyone can get past the RPoE. There’s an air of exclusivity around it. No one knows what lies beyond except we select few.

We who know to walk through the wall.

We who were told the day’s password.

We who opened the book.

The remarkable point of entry marks both the setting as someplace special, and the protagonist as someone special. Because the reader goes through the RPoE by way of turning the page, it marks them as special, too.

AN INCLUSIVE COMMUNITY

Readers like to see ourselves in books. Now that we have entered this setting, we must feel as though we can belong there. Few books truly succeed at diversity in regards to race and sexual orientation; however, authors have achieved an air of inclusivity by utilising a couple of different methods.

The first is by showing that different categories of people can live in this place. Think of the house system in Harry Potter. The cabins of camp Half-Blood. Include a system of categorisation in a place and readers will immediately sort ourselves into it and achieve a sense of belonging for it.

The second–and fiction’s favorite–method of showing that a setting accepts everyone is by populating it with misfits. Think of Neville and Luna in Harry Potter. In The Lightning Thief, Percy Jackson has both ADHD and Dyslexia. Where in the outer world, these cause Percy trouble, in Camp Half-Blood, these traits help him excel. It utilises the trope of the ‘misfit’ to best effect: it transforms the setting into a place where the things that make us different and weird turn out to be our greatest strengths.

The settings in these books provide a place to belong for those who might not have any other place to belong. The settings become places where readers feel as though they could not only belong, but succeed in, too.

A SENSE OF SAFETY

The setting must not only provide a place where anyone can belong; it is almost always a place of great safety. Hagrid refers to Hogwarts as one of the safest places on Earth. Percy Jackson is told he’ll die outside of Camp Half-Blood. The Shire is known for being quiet and safe.

This makes sense as a feature one might want a home to have. It is the reason places like Panem and The New World in The Knife of Never Letting Go, although well-constructed settings, aren’t places a reader might ever wish to be “welcomed home.”

Because of this, safety is a crucial feature of settings the might ‘welcome a reader home.’ Without it, a reader may revisit a story for the plot, or for the characters, but never because we wish to return to the setting itself. The reader must know that whatever adventures take place, things will turn out alright in the end.

UNAVOIDABLE ADVENTURE

Although the setting must be safe, it cannot be boring. For a setting to truly enchant a reader, it must come with the sense that once there, adventure will find them. The Shire is the best example of this.

Bilbo does not want an adventure. He says so outright when one is first suggested: ‘we don’t want any adventures here, thank you’ (Tolkien, 5). Nonetheless, he finds himself in the middle of one: ‘Mr. Baggins… was beginning to wonder whether a most wretched adventure had not come right into his house’ (Tolkien, 11).

Although adventure is rare in The Shire, the reader would likely identify with Bilbo, and feel if they lived in The Shire, they would be picked out for an adventure, too. In any case, they’d be in the right place for it.

You see this with Harry stumbling across the Mirror of Erised, with the sybil granting Percy a quest.

It’s a trope of the hero’s journey: there must be a call to action, the hero must reject the call, and something must happen so the hero is forced to take action anyway. The unavoidable adventure that sets the plots into action, but it does more than that. It makes the setting a place where stories occurs. This allows the reader to imagine that if we were there, then, surely we would fall into an adventure worth writing a book about, too.

How could we not?

It’s unavoidable.

AN ELEMENT OF THE FANTASTIC

This element makes good on the promise set out with the remarkable point of entry.

It’s most important and indefinable feature of a beloved setting.

This is the talking portraits and moving stairways of Hogwarts. The round doors, under-hill homes, and second breakfasts in the Shire. The deadly serious games of Catch the Flag at Camp Half-Blood.

It doesn’t necessarily have to magical, but it has to be unique and larger than life. The fantastical element is the ‘wow factor’ of a setting. It’s what makes the setting stand out in the reader’s mind. What truly captures the reader’s imagination. It is crucial for making a setting truly effective.

I’m not going to claim that this list is either prescriptive or comprehensive, but hope it might prove a starting point in transforming your setting from a place your characters inhabit, to a place your readers inhabit, too.

#oh this is SO COOL#thank you so much#will be refering back to this#writing advice#writing tips#writing

466 notes

·

View notes

Text

you know you're fucked up when it's Cardan who is the voice of reason

701 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the power of friendship osmosis.

“I don’t really know much about this thing, but my friend likes this thing. So by the transitive property, I like this thing and feel defensive over this thing on behalf of my friend. And if I see this thing while out with other friends, I will excitedly point it out and announce that it is the thing my first friend likes. I will also feel happy when I see it, as it reminds me of my friend, and time permitting, I will take pictures of it to show my friend later.”

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

two days until the biggest crossover event of the year, easter sunday and trans day of visibility (sincerely, a catholic transmasc)

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

just thinking about how "jude, you can’t really think i don’t know it’s you. i knew you from the moment you walked into the brugh." doesn't have to be specifically about jude taking taryn's place at the trial and cardan realising her disguise, it's also about the moment jude walked into the brugh for the first time when she was seven and every time after. he knew her.

701 notes

·

View notes

Text

In fifth grade a boy tried to impress me by swallowing a whole tadpole live and I punched him so hard that he puked and the tadpole was fine.

302K notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm so glad goncharov happened when it did, right before prolific public use of AI. that was pure honest gaslighting straight from the heart. real human whimsicality and trickery thru blood sweat and tears. we were a family. and we all gonched, together. you cant replicate that with any machine.

98K notes

·

View notes

Text

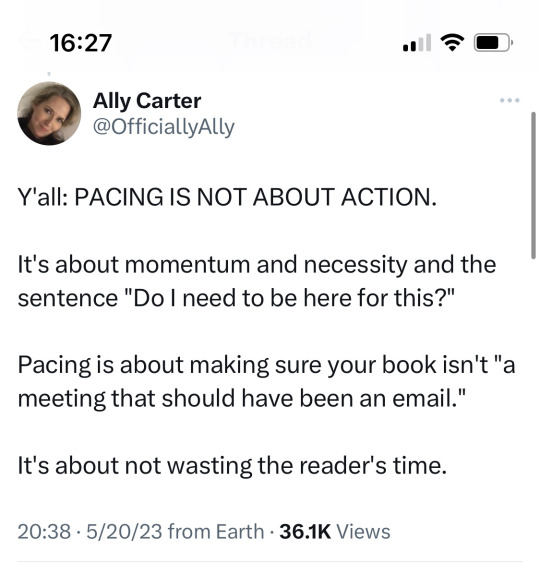

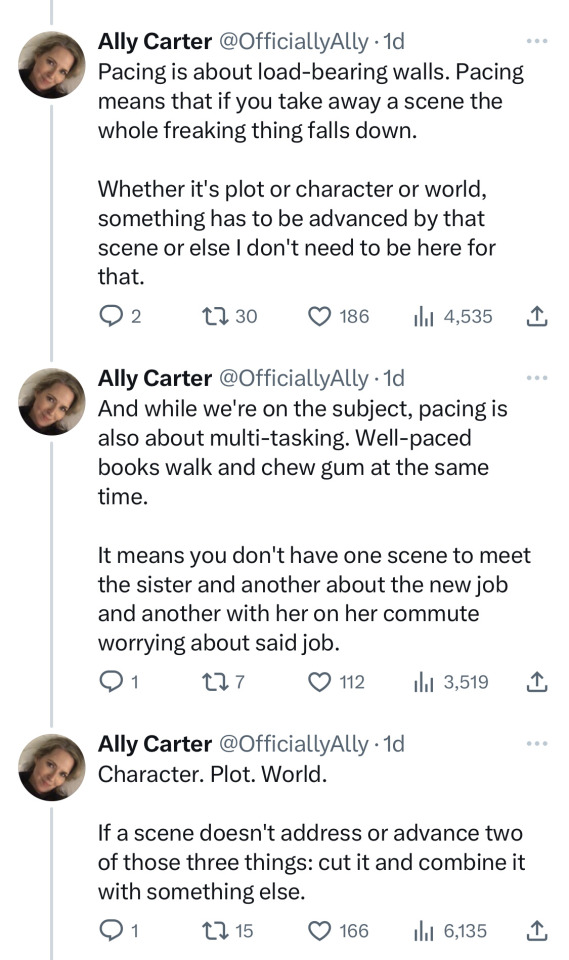

PACING IS ABOUT LOAD BEARING WALLS.

*staples violently to my own forehead*

24K notes

·

View notes