Text

On behavioral change, health and age

A Health Affairs article (Meyer 2021) discusses the potential benefits of Medicare Diabetes Prevention Programs (MDPP). MDPP aims to reduce patient weight and prevent patients from becoming diabetic. Commenting on her Medicare clientele enrolled in the program, one instructor noted:

“I’ve seen a lot of Medicare people do really well with the program because they have more time than younger people who are working or raising children,” she said. “But Medicare folks may have a harder time making [lifestyle] changes because they’ve been doing things the same way for a long time.”

MDPP was the first Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (a.k.a., CMMI; a.k.a., the CMS Innovation Center) demonstration of a preventive care model that was expanded to program available to al Medicare beneficiaries. However, uptake of the program is poor; only 3,600 Medicare beneficiaries across the nation have taken advantage of the MDPP benefit.

On behavioral change, health and age published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

How much money should governments spend to incentivize the development of new antibiotics?

As the number of infections that are anti-biotic resistant grows, we need to have more novel antibiotics in our arsenal. The problem is that many antibiotics are not commercially viable. For instance, if a new antibiotic is marginally better than the existing one, few payers will be willing to cover this cost. However, if new bacteria become resistant to the standard of care antibiotic, then the novel antibiotic would be highly valued. In short, antibiotics have a very high option value.

There have been a number of approaches to try to incentivize new R&D on antibiotics, including various prizes and subscription models.

The most prominent examples of antibacterial subscriptions are the pilot program created in 2019 by the National Health Service England (the UK pilot)14,15 and the Pioneering Antibiotic Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act, which was reintroduced in 2021 in the US Congress.16 In a subscription, the company is paid an annual subscription amount and agrees to provide as much of the antibacterial as is needed by the subscriber at no additional cost. As with earlier proposals to offer prizes for successful antibacterial R&D,17–20 one key question is the appropriate size of the pull incentive

A key question is how large these incentives should be. Some previous literature have proposed the following amounts:

Department of Health and Human Services. Push and pull incentives should be $919m (2012 USD) for a single indication. (Sertkaya et al. 2014)

Review on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR Review): Market entry rewards should be $800m to $1.3 billion USD, plus an additional $400m per year in research grants. (O’Neill 2016)

German Federal Ministry of Health’s Global Union for Antibiotics Research and Development report. $1 billion global launch reward–similar to a market entry award–plus $400 million in push incentives per year. Half of the $400m would go to preclinical research and the other half to clinical research. (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit 2011)

DRIVE-AB. The acronym stands for “Driving reinvestment in research and development for antibiotics and advocating their responsible use”; DRIVE-AB was a consortium of academics and industry experts. It was funded by the European Commission’s Innovative Medicines Initiative. DRIVE-AB recommended a $1 billion global market entry reward (pull), plus $800m in research funding (push) and ideally peak year sales of >$1 billion would lead to 18 new antibacterial medications over 3 decades. (Årdal et al. 2018; Okhravi et al. 2018)

World Health Organization (WHO) report. This report largely averages the estimates from previous reports. (Breyer et al. 2020; WHO 2020)

A paper by Outterson (2021) in Health Affairs published today aimed to update these estimates. He creates a net present value (NPV) calculation which depends on development cost (i.e., cost, duration and probability of success for any phase in the drug development process); revenues and expenses after antimicrobial approval; and the discount rate. The authors models different approaches to reach the NPV: based on global peak year sales (GPYS); based on a market entry reward paid in one year (MER1); based on subscription paid over ten years (SUB10); of based on the acquisition of a Phase II-ready asset (AQ). Using these approaches, Outterson finds that:

The partially delinked market entry reward required for an asset acquired at the initiation of Phase II was $1.6 billion (best estimate), with the upper and lower-bound estimates being $2.6 billion and $900 million, respectively (MER1 + ACQ). For a fully delinked subscription, the results are $3.1 billion (best estimate), with the upper and lower bounds being $4.8 billion and $2.2 billion, respectively.

The level of global peak year sales (GPYS) required for profitable antibiotic R&D is $1.9 billion (range: $1.6–$3.8 billion), which is a significantly higher sales amount than that achieved by any recent antibacterial. Only two antibacterials launched since 2000 have achieved $1 billion in peak sales: linezolid (Zyvox), with $1.353 billion in 2015 (launched in April 2000), and daptomycin (Cubicin), with $1.312 billion in 2016 (launched in November 2003)…

The partially delinked global market entry reward required (MER1) is $2.2 billion (best estimate), with lower- and upper-bound estimates of $1.5 billion and $4.8 billion, respectively…

The fully delinked global subscription required over the course of ten years (SUB10) is $4.2 billion (best estimate), with lower- and upper-bound estimates of $3.3 billion and $8.9 billion, respectively

The authors find that subscriptions are more expensive because (i) subscriptions are delinked from actual volumes and thus manufacturers must make the drugs without potentially any compensation (beyond the subscription); and (ii) payments are pushed into the future and thus additional funds must be found to compensate for the reduced time-cost of revenues received in the future. They also find that push incentives alone are typically insufficient to bring new antimicrobials to market.

The article is interesting throughout and do read the whole article here.

How much money should governments spend to incentivize the development of new antibiotics? published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Vaccine hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries

While the recently developed COVID-19 vaccines offer the hope of ending the pandemic, ending the pandemic is only feasible if individuals take the vaccine. In the US, a large portion of individuals report being hesitant to receive the vaccine. A key question then is whether individuals living in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) are have high rates of vaccine hesitancy.

A paper by Solís Arce et al. 2021 answers this question by conducting a survey of nearly 45,000 individuals living in 10 LMICs, Russia and the United States. The authors find that: , including a total of 44,260 individuals

The average acceptance rate across the full set of LMIC studies is 80.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 74.9–85.6%), with a median of 78%…The acceptance rate in every LMIC sample is higher than in the United States (64.6%, CI 61.8–67.3%) and Russia (30.4%, CI 29.1–31.7%). Reported acceptance is lowest in Burkina Faso (66.5%, CI 63.5–69.5%) and Pakistan (survey 2; 66.5%, CI 64.1–68.9%).

Across individuals who were willing to take the vaccine, the main reason for taking the vaccine was personal protection, with family protection typically coming in second place. Across individuals who were not willing ot take the vaccine, the main reason was concern over side effects, although some countries (Mozambique, Uganda and Pakistan) noted skepticism over vaccine efficacy.

Vaccine hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Mid-week reading

CBO analysis of the Build Back Better Act.

Information frictions helps explain why there isn’t more behavioral response to government interventions.

Wealth = networks, not assets.

Impact of same sex legalization on mental health.

Patient selection in CJR.

Mid-week reading published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

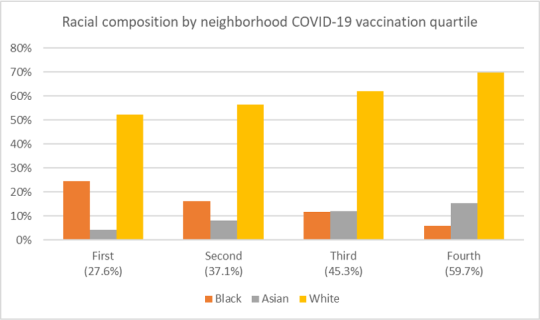

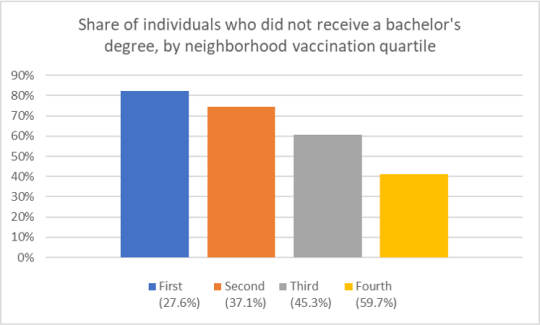

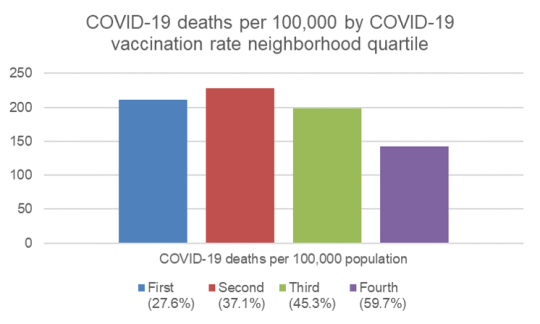

Characteristics of neighborhoods with high and low COVID-19 vaccination rates

What do the vaccination rates look like in the largest U.S. cities? In these cities, how do the characteristics of individuals in neighborhoods with low vs. high vaccination rates differ?

To answer this question, a paper by Sacarny and Daw (2021) use data from 9 large US cities: New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Phoenix, Philadelphia, San Antonio, San Diego, and Dallas. Specifically, they gather data on COVID-19 vaccination and death rates for these cites from health authority websites and sociodemographic information from the American Community Survey (ACS).

They find that neighborhood with high vaccination rates have: (i) more Whites and Asians and fewer Blacks and Hispanics, (ii) more people who received a bachelor’s degree or higher, and (iii) higher income levels, (iv) a higher share of individuals aged 65 and above. Unsurprisingly, COVID-19 deaths are lower in the highly vaccinated neighborhoods in these cities.

Characteristics of neighborhoods with high and low COVID-19 vaccination rates published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Cato supports public option?

A white paper from Cannon and Pohida (2021) calls for applying “public option principles” to Medicare. Who would have thought that the Cato Institute would call for a public option?

Well in fact, the do not really call for a public option. The proposal should be called introducing a voucher system into Medicare. Under the proposals, Medicare beneficiaries would receive a fixed voucher–adjusted for income and health status–that individuals could used to pay for premiums for whatever insurance they choose, public (Medicare Fee-for-service) or private (Medicare Advantage). The approach is not too dissimilar from one previously proposed by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) titled “The Best of Both Worlds.” The authors authors explain why they believe this would be a useful system, writing:

Economists have proposed eliminating these perverse incentives by having Medicare directly pay each enrollee a fixed subsidy the enrollee can apply to either traditional Medicare or private insurance. Program administrators would take the money Medicare otherwise would pay to providers and insurers and give those funds directly to enrollees as a monthly payment, just as Social Security does. In 2022, they would divide $783 billion among the program’s 66 million enrollees, such that enrollees would receive an average subsidy of $11,900. Medicare would then adjust individual allotments according to each enrollee’s health status and income (see below), such that all enrollees could afford a standard health insurance plan comparable to traditional Medicare. The net effect is that enrollees would receive approximately the same subsidy they would under current law.

A key issue is how well can people shop across plans. Are quality measures clear? Are the meaningful? Are they free from provider gaming?

The authors cite a paper where Don Berwick–a former CMS administrator–notes that the current provider payment schemes may not incentivize quality.

Even if payment schemes were sensitive to quality, and even if consumers could see the difference between better and worse care, [incentives for quality] improvement would be weakened by the distance between the patients and the payment rules. People and payers who might be quite willing to pay a premium for more fully integrated chronic disease care, for the option of a group visit, or for detailed management of their lipid medications do not have the option to do so because of fixed fee schedules and complex payment rules. This is particularly true under Medicare. In effect, people do not have the option to pay for what they want, even if what they want is better than what they have.

As I posted recently, Medicare now has a large number of value-based programs, but not many of these alternative payment models have had a large impact on quality.

The authors claim that the voucher-based system will lead to more creative ways to pay providers.

…public-option principles require eliminating favoritism toward fee-for-service payment, or whatever payment rules the government plan happens to employ. Applying that principle to Medicare would increase demand for prepaid group plans and other non-fee-for-service arrangements, promoting dimensions of quality Medicare currently discourages

Also, more standardization of health plans makes it easier to shop across plans; standardizing, however, leads to less innovation as well. The major underlying assumption is that by allowing more competition, cost should fall and outcomes should rise. Skeptics would point out that administrative costs will likely rise as health plans compete and there could be more cost savings with a single payer option. While the later point is valid in a static setting; over the long-run competition tends to be the most effective way to bring down cost.

Another key issue is, how does one adjust for health status and income? While in principle this is easy to do (Medicare Advantage already has their subsidies from CMS risk-adjusted for health status), in practice health systems and insurers may have more information than does the government when making this adjustment. Further, transitory employment shocks–while less of an issue for the Medicare population–can make estimating individual income a challenge.

Despite these numerous challenges, the idea is interesting and the white paper is worth read.

Cato supports public option? published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Weekend Reading

Here are some questions to get your weekend reading started.

Can Yelp predict hospital mortality?

Can AI solve a radiologist shortage in the UK?

How do we get the LA/Long Beach port back up and running?

Why is CMS in Baltimore rather than DC?

What to do when you’re down to your last diaper?

Weekend Reading published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

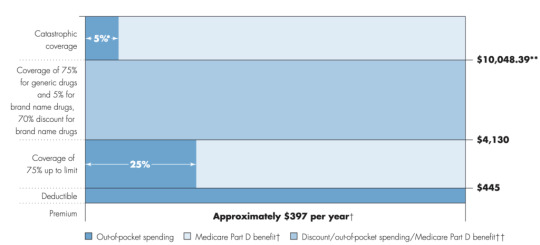

Part D Senior Savings Model: What is it?

If you are on Medicare, how much will you pay for insulin? The answer is in the graph below (via MedPAC’s Payment Basics)

Seem confusing? Well it is. Medicare Part D beneficiaries have a deductible, then the standard coverage phase with 25% cost sharing, then a coverage gap where beneficiaries pay 25% of cost (manufacturers cover 70% of the cost for branded drugs in this coverage gap), and then a catastrophic phase where beneficiaries pay 5%. Wouldn’t it be easier if there were simple copayments like many commercial plans?

That is what CMS has been trying out in their Part D Senior Savings Model. The model includes fixed copayments for certain enhanced Part D plans. CMS writes:

The voluntary Model tests the impact of offering beneficiaries an increased choice of enhanced alternative Part D plan options that offer lower out-of-pocket costs for insulin. CMS is testing a change to the Manufacturer Coverage Gap Discount Program (the “discount program”) to allow Part D sponsors, through eligible enhanced alternative plans, to offer a Part D benefit design that includes predictable copays in the deductible, initial coverage, and coverage gap phases by offering supplemental benefits that apply after manufacturers provide a discounted price for a broad range of insulins included in the Model.

As described by former CMS administrator Seema Verma in the Health Affairs blog:

MS’s Part D Senior Savings Model is designed to lower prescription drug costs by providing Medicare patients with Part D plans that offer the broad set of insulins that beneficiaries use at a stable, affordable, and predictable cost of no more than $35 for a 30-day supply…beneficiaries who do not qualify for the low-income subsidy (LIS) currently pay 5 percent of the negotiated price when they reach the catastrophic phase, which should be lower than $35 in most cases. Part D sponsors could offer lower copays than $35 and still maintain all formulary flexibilities and choices.

Sharon Jhawar, Chief Pharmacy Officer at the SCAN Health Plan argues that the Senior Savings Model is working, should be made permanent, and should be expanded to both other diabetes medications and medications used to treat other common chronic conditions. Previous research shows that cost is a barrier to medication adherence, and she writes:

Let’s accelerate the timeline for making the Model permanent and use the expected cost-savings ($250 million per year) to advance other health initiatives for Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes…Yet diabetes is only the fifth most common chronic condition among Medicare beneficiaries. People with other chronic conditions, such as heart conditions, neurological conditions, or auto-immune diseases, will encounter the same financial challenges we see in the diabetes medication scenario. With a successful template in place to manage costs, we have a unique opportunity to reduce prescription costs across the board.

For more information, read the CMS Senior Savings Program Fact Sheet and visit their website.

Part D Senior Savings Model: What is it? published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

CMMI and its revised strategy

Created by Section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI; aka The CMS Innovation Center) has been tasked with creating new reimbursement strategies to improve quality and decrease costs. Over the past decade, CMMI has tested over 50 new payment models, and in just the last 3 years (2018-2020) CMMI models have reached almost 28 million patients and over half a million health care providers and plans.

Despite these ambitious goals, CMMI reports that “only six out of more than 50 models launched generated statistically significant savings to Medicare and to taxpayers and four of these met the requirements to be expanded in duration and scope.”

In their recently released white paper “Innovation Center Strategy Refresh.” CMMI claims to have learned the following lessons:

Ensure health equity is embedded in every model

Streamline the model portfolio and reduce complexity and overlap to help scale what works.

Tools to support transformation in care delivery can assist providers in assuming financial risk.

Design of models may not consistently ensure broad provider participation.

Complexity of financial benchmarks have undermined model effectiveness.

Models should encourage lasting care delivery transformation.

Some interesting points from the report include:

Medicare FFS beneficiaries will be in an accountable care relationship with providers and will have the opportunity to select who will be responsible for assessing and coordinating their care needs and the cost and quality of their care.

The above seems obvious, but previously, beneficiaries were attributed to physicians typically based on the number of physician visits (often just evaluation and management [E&M] visits). This meant that some patients who would be overseen by a specialist during an acute bout of a disease would be then held responsible for all of a patient’s cost. Further, neither the patient nor the provider would know to which physician the patient would be attributed. While this approach may seem confusing, the benefit was attribution could be done passively; while more active attribution probably makes sense, it is unclear whether patients will actively select providers to manage their care or what will be needed to incentivize patients to do so.

The CMS Innovation Center will address barriers to participation for providers that serve a high proportion of underserved and rural beneficiaries, such as those in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs), and designated provider types such as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), rural health clinics (RHCs), and other

safety net providers and create more opportunities for them to join models with supports needed to be successful.

A key question is how CMS will do this. One approach would be to set lower quality or less strict cost evaluations for these types of providers. While doing so would make participation in alternative payment models more attractive, it would also create a two-tiered system with lower quality standards for disadvantaged beneficiaries in HPSA and MUAs who are often treated at FQHCs, HCS and other safety net providers. CMMI have not spelled out explicitly how they plan to accomplish this equity quote. The only concrete action CMMI mentions is collecting data on race, ethnicity and geography to examine health disparities.

Drawing on more diverse beneficiary, caregiver, and patient perspectives will systematically inform development of models that test care delivery changes and innovations that are meaningful and understandable to them….Providers participating in models, particularly total cost of care models, will have access to more payment flexibilities that support accountable care, such as telehealth, remote patient monitoring, and home-based care.

This is clearly a good idea. How to implement more patient-centered care, however, is a challenge. It is good to see that CMS is considering allowing for payment flexibilities around telehealth going forward, but it is not clear why this flexibility would only be extended to providers in total cost of care models; all providers should be able to leverage telehealth to improve patient access and outcomes, not just those in total cost of care models.

CMMI also proposes to lower beneficiary out-of-pocket cost spending, but focuses only on increased use of generic and biosimilars. The Innovation Center also calls for the use of value-based insurance design (VBID). While VBID is sensible, health economic analysis will be needed to determine what treatments qualify as “high-value” and would be subject to low patient cost sharing.

To achieve some of these goals, the CMS Innovation Center aims to go ‘all-in’ on value-based reimbursement and is attempting to expand these payment schemes beyond Medicare. Specifically, they aim to measure their progress as follows:

All Medicare beneficiaries with Parts A and B and most Medicaid beneficiaries will be in a care relationship with accountability for quality and total cost of care by 2030.

Where applicable, all new models will make multi-payer alignment available by 2030.

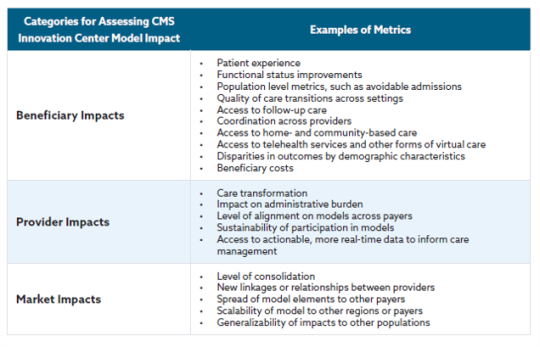

Below is a table describing how CMS will measure success for different stakeholder groups.

There is much more in the white paper and you can read the full document here.

CMMI and its revised strategy published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

The Pitfalls of Cost Sharing in Healthcare

Cost sharing is just that, sharing in the cost of providing a health care service. While health insurers often pay for a large share of health care cost (for those covered), individuals also contribute through deductibles, copayments and coinsurance. The goal of cost sharing is to reduce moral hazard. Moral hazard occurs when the price of a good is below its marginal cost, people will consume more of it. However, because the benefits of health care treatment are often long-term, can be difficult to observe, and often come with side effects, the costs and benefits that a patient observes may not be the same as the actual cost of production and cost sharing may discourage the use of cost-effective, high-value medical or pharmaceutical interventions.

Aaron Carroll at Incidental Economist provides nice overview summary of the potential benefits and key pitfalls of cost sharing.

youtube

This video was adapted from a column written at the Upshot and links to sources can be found there.

The Pitfalls of Cost Sharing in Healthcare published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Center for Healthcare Economics and Policy brochure

Check out FTI Consulting’s Center for Healthcare Economics and Policy‘s new services sheet here. The cover page and overview of some of our HEOR services are below.

More details on the full scope of health economics services that we offer can be found here.

Center for Healthcare Economics and Policy brochure published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Friday Links

A taste of their own medicine?

Impact of COVID-19 on mental health.

COVID-19 vaccines work for veterans.

No mandate but make the unvaccinated pay their own way?

Patient-focused drug development.

Friday Links published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

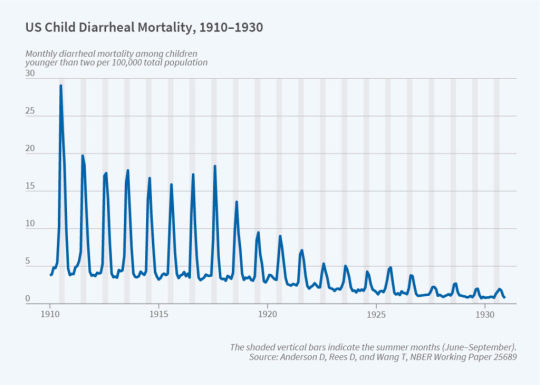

The impact of public health efforts on US Mortality

Research by D. Mark Anderson, Kerwin Kofi Charles & Daniel I. Rees in the NBER report provides some useful graphs looking at how various public health interventions have impacted health outcomes in the U.S over the last century. Specifically, the authors show that public health interventions aimed at improving the health of the municipal water supply had large impacts on both mortality for some groups, illness, and inequality of health outcomes. Regarding the latter point, the authors find that:

…chlorinating the water supply, which was relatively cheap, had no observable effect on the White infant mortality rate (IMR), but led to a 9 percent reduction in the Black IMR and a 10 percent reduction in the Black-White IMR ratio — our measure of the Black-White infant mortality gap. Moreover, we found that adding chlorine to the water supply narrowed the Black-White infant mortality gap, at least in part, through its effect on diarrheal disease.

More details are available here.

The impact of public health efforts on US Mortality published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

2021 Nobel Prize in Economics goes to Card, Angrist and Imbens

The 2021 Nobel Prize in Economics goes to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens due to their work on “natural experiments” and how this econometric technique can inform important research questions in labor economics. From the Nobel Prize press release:

Using natural experiments, David Card has analysed the labour market effects of minimum wages, immigration and education. His studies from the early 1990s challenged conventional wisdom, leading to new analyses and additional insights. The results showed, among other things, that increasing the minimum wage does not necessarily lead to fewer jobs. We now know that the incomes of people who were born in a country can benefit from new immigration, while people who immigrated at an earlier time risk being negatively affected. We have also realised that resources in schools are far more important for students’ future labour market success than was previously thought.

Data from a natural experiment are difficult to interpret, however. For example, extending compulsory education by a year for one group of students (but not another) will not affect everyone in that group in the same way. Some students would have kept studying anyway and, for them, the value of education is often not representative of the entire group. So, is it even possible to draw any conclusions about the effect of an extra year in school? In the mid-1990s, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens solved this methodological problem, demonstrating how precise conclusions about cause and effect can be drawn from natural experiments.

Difference-in-difference. One well-known natural experiment examined how minimum wage laws affects labor markets. A paper Card and Krueger (1994) compared nearby fast food restaurants in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Fast food restaurants in the former state experienced a change in minimum wage laws whereas the latter did not. Card and Kruger look at the change in employment in NJ and compare it to changes in employment in PA. They stated that there was “no indication that the rise in the minimum wage reduced employment”.

Instrumental variables. Angrist and Imbens (1991) used instrumental variables (IV) to answer a number of questions such as examining returns to school. Alex Tabarrok provides a nice overview of how discrete cutoffs (e.g., ability to start school if born before Jan 1, but not if born after; ability to leave school at age 16), provide an exogenous source of variation on the months of education. Another canonical IV example pioneered by Angrist is the study [Angrist 1990] looking at the impact of military service on lifetime earnings. Since characteristics that predict military service may predict earnings as well, ideally one would randomize people into military services vs. not. Of course, this type of randomization is not feasible, but instead Angrist used information on an individuals’ Vietnam draft lottery number as an exogenous source of variation. The IV approach allows one to estimate the local average treatment effect (LATE) for compliers (i.e., those would would join the army if drafted, but would not join if not drafted). Using this IV approach, Angrist finds that “the earnings of white veterans were approximately 15 percent less than the earnings of comparable nonveterans”. Angrist also has a nice, short book on econometrics with Jörn-Steffen Pischke titled Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion.

There is lots more coverage if you’re interested: Krugman at NYT, CNN, FoxNews, BBC, Bloomberg.

2021 Nobel Prize in Economics goes to Card, Angrist and Imbens published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Which health systems are providing low value care?

That is the question posted by Ganguli et al. (2021). The define low value care as one of 41 specific services. They then use data across 556 health systems serving more than 11m beneficiaries to answer this question.

Which types of low value care are most commonly used?

The most common low-value services were preoperative laboratory testing (mean [SD] rate, 28% [4%] of eligible beneficiaries), prostate-specific antigen testing in men older than 70 years (mean [SD] rate, 27% [8%]), and use of antipsychotic medications in patients with dementia (mean [SD] rate, 24% [8%]).

Health system characteristics associated with increased rates of low value care include:

Fewer primary care physicians,

No major teaching hospital

A larger share of minority (i.e., non-White) patients

Located in South or West

Serving areas with more health care spending

Quality of care includes both positive and negative actions; that is performing high-quality, high-value services and avoiding low-quality, low-value services. While this study only examines one side of this coin, it does show that there is still room to improve to reduce the use of low-value services.

Which health systems are providing low value care? published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Friday Reading

Favorite paper.

Covered California’s out-of-pocket drug max

Google moves to first price auction.

FDA on RWD for regulatory decision-making.

NBA and health care fraud.

Friday Reading published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes

Text

Should policymakers use a social discount rate?

Discount rates are commonly used in the world of finance. Would you rather have $1 today or $1 in 5 years? Most people would prefer $1 today. For instance, if you had $1 today and put it in a bank account, it would be worth more than $1 in 5 years. Thus, when making financial decisions, firms and many individuals consider funds received today to be more valuable than those in the future.

An important question is, should we use a social discount rate? For instance, consider the impact of global warming. Averting global warming will have immediate costs but the benefits would accrue to future generations. Should we use a social discount rate to “discount” the benefits received by future generations in any cost-benefit analysis?

According to a paper by Cowan and Parfit (1992) argue that a social discount rate should not be used when making policy decisions. Their logic is as follows:

Argument from democracy. What if the majority of voters prefer put more weight on current cost and benefits and downweight future cost and benefits? Cowen and Parfit argue that this is not an ethical argument because the individuals adversely affected by a social discount factor–i.e., future generations–are not able to vote on the policy.

Argument from probability. Events that may happen in the future are less certain. Thus, one may argue that we should discount future costs and benefits because we are less certain about them. This argument, however, is more about the precisions of the cost-benefit analysis than the fact that future costs and benefits should be down-weighted. A more persuasive argument, however, may be that in the future new technologies may make it less expensive to address any costs that occur in the future. If this were the case, however, the true impact of technology on costs could be modelled explicitly rather than addressed in a more ad hoc way through the social discount rate. This is particularly true since uncertainty/impact of technology is unlikely to proceed at a steady, linear pace as would be applied using a social discount rate.

Argument that our successors will be better off. If the economy continues to improve over the long-run, future generations will be better off than the current. If we care about equality of outcomes, we may want to discount the benefits that accrue to future generations. However, a more practical approach for implementing this goal would be to use a Rawlsian approach with an explicit aim that benefits should be shared across generations. This could be implemented using a distributional cost effectiveness analysis (DCEA) across generations rather than using an ad hoc social discount rate.

Argument on excessive sacrifice. Some may claim that without a discount rate, people may be forced to sacrifice now if the return on investment for future generations is high. While that is a concern, another concern is the following. Should individuals make a small sacrifice now to average a minor catastrophe in the near future or make the same (identical) small sacrifice to avert a major catastrophe in the distant future. With a social discount rate, sacrificing now for the minor, nearer-term catastrophe may be preferred, even though most individuals would say the major catastrophe is the preferred option.

Argument on special relations. So far we have discussed policy issues, but individuals also make decisions about the future affecting future generations and many do so, without discounting future outcomes. In fact, many parents would seem to have a negative social discount rate if they prefer their children (and grandchildren) to have better outcomes than themselves.

Perhaps the best argument is just to implement the math.

According to a social discount rate of 5 percent, one statistical death next year counts for more than a billion deaths in four hundred years.

The paper continues with economic arguments against a social discount rate (e.g., opportunity cost, marginal productivity of capital, positive time preferences) as well as some challenges in using altruism or bequests to justify a social discount rate.

Do read the whole article.

Should policymakers use a social discount rate? published first on your-t1-blog-url

0 notes