Text

What Makes a Good Board Game Expansion

Hello all, today I’m going to be delving into the various board game expansions I have and talking about a few of them, trying to assemble an overall sense of what makes for a good expansion and what makes for a less worthwhile one.

What often doesn’t work #1: Nothing but more content

Perhaps the most low-hanging fruit to expand a board game is to just add more stuff. Is there a central deck of cards? Add more cards. Are there action spaces? Add more spaces. The advantage to this approach is that it’s often easy to design, and it adds minimal learning overhead to the expansion. However, there are a few disadvantages - a lot of games are built to be very tight, finely tuned engines around either the frequency of various card types or the availability of certain resources or spaces. If you add more cards in, sometimes that tuning will be directly thrown off. Even if you make an effort to adjust for it, the increased variance may impact the game (if you have a 50 card deck with 10 each of 5 types of cards, and players draw 45 cards from it over the course of the game, that’s going to lead to a much different set of distributions than if you have a 100 card deck with 20 each of 5 types of cards and 45 cards are being drawn). But overall, the biggest issue is that this rarely feels exciting or new, unless the game is built around the cards and the expansion adds particularly vivid new cards. Of course, sometimes an expansion will naturally add some extra elements (If an expansion adds a new resource or mechanic to a game with a central card deck, it makes sense to also add on a few cards that interact with that resource or mechanic - this is totally fine if those cards are just supporting an innovative idea, and aren’t the central focus of the expansion)

Example: Lords of Waterdeep: the Undermountain

The first mini-expansion to Lords of Waterdeep adds new quest cards, new buildings, and a few new action spaces. The new cards and buildings are fine, if unexciting, but the new action spaces undermine the core balance of the game; purple and white cubes are extremely rare in the base game, so adding even 1 more location where you can grab them instantly lightens the sweet tension by too large an amount.

What often works #1: Add some asymmetry

Games often have to watch carefully how much of an impact choices that players make before the game starts have. In a world where a lot of people would rather try out several games once than play the same game several times, forcing players to make an important decision early on can be a recipe for disaster, since they could set themselves up for failure based on inexperience. In an expansion, this goes out the window - presumably your audience enjoyed the core game and has played it at least a few times before buying the expansion, so a great way to liven a game is to add an asymmetric element, player characters with unique abilities, or anything along those lines.

Examples: T’zolkin the Mayan Calendar, Teotihuacan

There are at least 3 or 4 games by the Italian designers Danielle Tascini and Simone Luciani that follow this approach - one of the main elements included in the expansion is a set of asymmetric player powers that players will select before the game begins. This mixes things up, makes players see even the existing elements of the game in a new light through the lens of their power, and creates significant replay value, since you’ll want to try the game with each power. 7 Wonders does a similar thing in its terrific Leaders expansion.

What often doesn’t work #2: Add another type of resource

Much like #1, this is a natural design vein. Players are collecting 4 different types of resources in your Euro game? Why not add a 5th in the expansion? However, unless that resource is collected or used in a substantially different way than the others (and sometimes even if it is), this is just going to feel like more of the same with a different name. Furthermore, the more different types of resources there are to chase, the more the design will often feel watered down.

Examples: Everdell Pearlbrook, Terraforming Mars Colonies (specifically the Floaters resource & cards)

Pearlbrook is an example of how hard this second type of expansion is to get right - it adds a new resource, pearls, which are acquired in a new way using an entirely new type of worker and spent on several new things, and yet to my taste it still comes away feeling like it didn’t add much to the core game.

What often works #2: Add something that puts everything in the game into a new context

This may be easier said that done, but a common trait of the best expansions is that they’ll take the core gameplay of the original game and add just 1 or 2 things, but those things will be so central and so game changing that the other elements of the game will feel new as well as you interact with them in a new way.

Example: Dominion Prosperity

The Prosperity expansion for Dominion adds a few new cards, many of which are interesting, innovative, and fun. However, the big change is that in the original game, you were racing to collect victory point buildings that cost $8. With Prosperity, there are buildings that cost $11 and grant even more points. This is a huge change, and it makes you reconsider any cards you might have loved or hated before, as a slower, longer game rewards you more for thinning out your deck of weak cards and picking up flexible actions, while making certain coin-granting cards less powerful.

What may work: Fix something broken from the base game

Is your game good, but with one element that players really hate? Is there one aspect that you never quite figured out, but of course as soon as the ink dried on your printed copies you realized the perfect solution? An expansion may be a good place to fix these things, as long as that isn’t all that you include.

Example: Kingsburg To Forge a Realm

The original Kingsburg had a woeful military system - creatures of unknown strength would come out at the end of each year, which you would need enough strength to beat or face huge, game-altering consequences. In the original game, you took any military strength you had, and one die was rolled for the whole table, so it was easy for a player with a lot of strength to have wasted it with a high roll or a player who had enough strength to be fine the vast majority of the time to be knocked out of the game by a ‘1′. Kingsburg’s expansion adds many things (including asymmetric player powers - see point 1 :) ) but one thing it does is fix the military system. Now, there is no die roll - instead each player has a pool of tokens of various strength, and they pick one to use each year. This adds to the suspenseful reveal while putting a few interesting decision points into the game, vastly improving the weakest element of Kingsburg.

That’s all I have for today, hope this was interesting to you!

0 notes

Text

John’s top artists and influences!

Following up Mia’s post, I thought I’d go through a few of my own top few artists, and talk about how they influenced my work in Lemon Knife. I’m going to go chronologically:

Talking Heads

The Talking Heads were the first band I started listening to that wasn’t a group my parents introduced do. I borrowed Little Creatures from a friend (though I think it was actually his parents’ CD), enjoyed it a lot, and then asked for Stop Making Sense for Easter when I was 13. I immediately fell in love with the Talking Heads as a kid because of how goofy the songs were. A song about a psycho killer? About things burning? Sign teen John up! A lot of the other music I had heard (and still a lot of music out there) is myopically focused on love, heartbreak, romance, sex, etc., and as a teen geek/ace (though I didn’t know that part at the time), all of that was the furthest possible from relevance to my life. I loved the Talking Heads because they sung about different things and quirky things, and that love holds up today and inspires me to try and make interesting lyrics or take on interesting points of view. They also combined those lyrics with arrangements that were both well-made and extremely danceable, making every element of each song stand the test of time.

Queens of the Stone Age

QotSA were a band I heard from their songs in Guitar Hero and Rock Band as a teenager, quickly enjoyed the sound of, and soon sought out their most acclaimed album Songs for the Deaf. Songs for the Deaf is a fantastic album all around, but to get particular, that album is probably my biggest influence as a drummer (coupled with the other Homme-Grohl collaboration, Them Crooked Vultures) - I love the raw energy Dave Grohl brings to the drums on it, the hard-hitting fills, and the almost mathematical structure he gives the parts. Dave knows when to throw in a crazy fill, when to throw in a simple but fast and powerful beat, and when (rarely) to play something more mellow to give space to the rest of the band - I can only hope I end up as good a drummer as he is on that record.

Warren Zevon

I got into Warren Zevon later in high school, and his lyrics had a similar influence to the Talking Heads. Warren would pick all kinds of interesting themes and perspectives for his lyrics, while infusing them with a consistent clever cynicism that I also loved.

Crazy Arm

For those tragically unaware, Crazy Arm are a British folk/punk band who have made a wide range of excellent music but remain relatively little known outside of (and possibly even within) the United Kingdom. I downloaded their albums Union City Breath and Born to Ruin in high school, and probably the biggest influence they had on me was opening me to the fact that a band doesn’t have to just play one thing. The Sex Pistols just play punk, and that’s fine. A lot of folk singers just strum acoustic guitars, and that’s fine too. But Crazy Arm, and another of my favorite artists Frank Turner, play with a huge variety of sounds. Just on Union City Breath alone, they have a purely acoustic ballad, a full speed fiery punk song, a lot of midtempo rock songs, and many variations and shades in between. That variation inspired my songwriting/structure building with Lemon Knife - the first song we ever wrote was a hard rock song built around a Muse-inspired riff Mia had prepared, while the second was a superfast punk song. From there, we’ve tried to explore as much as possible while keeping a somewhat consistent sonic palette so that there’s still some root identity. I love that on each of our albums so far, there are several songs that sound like nothing else we’ve made, while still sounding like Lemon Knife.

0 notes

Text

Guest post: Mia!

This week, I thought it would be fun to have my bandmate in Lemon Knife and girlfriend in lemon life, Mia Blixt-Shehan, write a post for some variety. I asked her to write about her favorite bands and how they influenced her work in Lemon Knife, and you can read her post right below:

So, I’m a Guest Writer for a blog! Exciting times! Really! Look, I’ve had this title exactly once before (https://www.writebynight.net/news-events/wfpl-rats/), where I made the interesting (read: ill-informed) decision of pawning off the first chapters of a thirteen-year-old novel—by which I mean I was thirteen years old when I tried to write the stinking thing (what was I doing trying out novel writing at thirteen?)—about the coming of age of a group of British sewer rats who decide to migrate to America in the era of Beatlemania…???...to promote a now-defunct blog under a now-defunct nom de plume. I’ll gladly take my second chance to appear on someone else’s blog without completely exposing the gaps once filled by my long-lost tween-aged marbles, thanks very much!

Well, anyway…of course, I have a bit of a personal attachment, to understate things—the blog’s author is my dear bandmate and partner, John, so I, Mia, am here to write about my top three favorite musical artists and how they made a mark on the excellent duo that is Lemon Knife! I hope you enjoy my stop by and learn a few things as well. Here we go, lowest- to highest-ranked:

3. Muse

Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story of the air raid siren with the bass. Lowercase—The Air Raid Siren is the formidable Bruce Dickinson, obviously, I can’t take that title. But I’d be an effective red alert nonetheless—“EEEEEEVAAAAAACUUUUUUAAAAAAAATE IT’S A MOOOOOOOOONSOOOOOON!!!!”…new Lemon Knife lyric?

Before my love affair with the Muse discography began just five or so years ago, however, I wasn’t an air raid siren but a coffee shop bulletin board flyer. At this point I’d finally become semi-comfortable with my instrumental abilities, in specific circumstances, anyway, but I was still terrified of singing louder than, like, 25 decibels. I knew my voice was imperfect and didn’t really want to use it for much. The potential use of my vocal imperfections finally clicked on the fateful day where I heard the Black Holes and Revelations album for the first time (of at least ninety since). Loosely recommended by a visiting librarian when I was a library page, it was something I remembered only by fate on my usual very long train ride to college one day—“sure, let’s stream this thing, this train is stuck and I’ve got nothing better to do!” And there it was, as I sat spellbound through the opening track, “Take a Bow”—I was listening to a voice I hadn’t heard the likes of before, though I couldn’t quite place how it was so distinctive at the time. This was something greatly commanding and uniquely beautiful, and something that evoked copious amounts of whatever song’s emotion without sacrificing the ability to sound genuinely stinking good, and I wanted to know how it was done straight away. And so, after the last notes of “Knights of Cydonia” had died away, I set to figuring out the keeper of that voice—the magnificently brilliant Matt Bellamy—and diving into the music and generally obsessing over every recording I could unearth on my lengthy train rides. Good college pals, Muse were…

In the depths of my weekly Muse analysis (weekly classes, you know) I also became fascinated with the instantly recognizable bass work in the band, granted to the listener by the utterly fantastic Chris Wolstenholme. This isn’t your typical fuzz bass by any means. It’s got every amount of effect manipulation and gear tweaking and all—the—pedals—yet it’s combined with a great and distinctive technique that ensures that unlike that of too many other bands of their era and just before it (looking at you, Green Day!), their bass will almost certainly never become a lesser part of the music. It was here that I heard about another distorted bassist that was openly inspired by Muse and took it to the next level—he was Mike Kerr, the sole melodic instrument (well, besides vocals!) in a little band called Royal Blood. And it was THERE that I realized that bass/drum duos could be a thing…and…well…what do you think happened next?

2. The Who

We’re going a pretty hefty step up in influence here—I wouldn’t be a fuzz bassist and air raid siren vocalist without Muse, but I wouldn’t be a musician at all without The ‘Orrible ‘Oo.

It’s a story I’ve told countless times and will forever retell: Right around the extremely tender age of five, I came across a VHS (remember those?!) of the original Who rockumentary, decades before the squeaky-clean presentation of Amazing Journey—I speak of The Kids Are Alright. Familial lore dictates that the music of Neil Young was an immediate sedative when I was kicking hard in the womb, but a few years out of it, this was the first time I’d been exposed to music so raw and raucous and explosive…literally and figuratively. It had clearly seeped into my underdeveloped brain as an obsession grew through the years. (The first piano chords I learned outside of classical training were the ones in “Baba O’Riley,” at my independent request.)

At thirteen—oh, yeah, when I was also trying to write a novel about rats!—I got my first guitar. I took a few lessons for some months with a couple of fantastic tutors and then I was off on my own with a self-prescribed in-depth study of acoustic Who songs. I can’t imagine I was a particularly typical student, because from the very beginning I had absolutely no interest in learning to Van-Halen-shred and very little in the Gilmour bend, even though I greatly admired both—I was in deep with the Townshend -sus4 chords and vicious pick attack. To this day my right hand is ridiculously gritty with sets of both six and four strings, more so with my choice of using coins as plectrums (we’re about to get to that). Eventually I decided to abandon soloist peer pressure entirely and focus hard on rhythmic playing and making songs melodically interesting, which, filtered through The Who, greatly informed my later interests in both musical composition and the deep dive into bass. Rock composition came easily—much easier than lyricism, then and now—after spending so much time with my head in the Who discography, with the instantly recognizable chord structures and ever-expanding boundary-pushing within songwriting (flailing rhythm guitar! Lead bass guitar! ARP-2600s! Rock operas!!), and my decision to pursue bass was solidified by John Entwistle, the band’s resident Ox and my four-string hero to this very day.

1. Queen

Oh, buddy! This is it! This is the point of the article where we start really jumping up and down about things—like, if you thought those other two entries were fanatical, well, ohhhh, buddy!!

Queen! Yes! The greatest band on Earth, then, now, and onward. Well—to me. It’s all subjective, I’m aware. But the greatest band on Earth. Really. Here are four guys that took rock by its legs, stood it on its head, and spun it around until the very soul of it was changed for good. The way I see it, there are two schools of musical artists in the current era—the ones that mostly grew up on everyone else in the 1970s, and the ones that mostly grew up on Queen. You can always tell who they are if you have the innate sense, which often comes to you by being a fellow Queen fan. The Struts. Fun. (fun., actually.) Mika. The Killers. And in news that should surprise no one reading this, three of the most obvious Queen fans in music make up Muse. They can’t be understated.

Let’s look at this further—what did we have here? The most “duh” answer first—we had the greatest frontman in the history of any style of music, I’d venture to say, in Freddie Mercury. Need I say more about him—really?!? We had a bassist that told miniature stories within his prominent sound in John Deacon. We had Roger Taylor, the human drummer who was “more reliable than a drum machine,” the primary utterer of THOSE harmony high notes, and, as it turned out, probably the most experimentally minded member of the band if his solo career is any indication. And last but most certainly not least, we had a guitarist who literally crafted one of the most immediately known tones in rock with his bare hands (from a fireplace!) and pushed every boundary of the instrument in Brian May. Whose musical presence, by the way, essentially saved my life way back when. (I was about to say that there should be shirts made with the statement “Brian May Saved My Life” on them, but I immediately recognized how terrible of an idea that would actually be, although I wanted it known that it passed through my brain, so yup, here’s a parenthetical on it. Voila.) Many apprehensive people who eventually get into music see themselves for the first time in a tough-as-nails leather-clad punk goddess, or a platform-wearing out-and-proud queer, or a genre-blending, every-line-crossing, overall bad-arse POC. I saw myself in a frizzy-haired nerrrrrrrd equally inclined to embroil himself in academics (astrophysics in his case, anthropology and library science in mine) and jet onstage to make himself very known in a rock band. A convincing argument to be sure.

Okay! That was a while. It was. I hope it wasn’t too much of a while. If you made it here, congratulations—and thank you! Lemon Knife is a happy endeavor indeed—maybe we’ll see you at a show!!

0 notes

Text

Hidden Trackable Information in Board Games

Hi all! Today I'm going to be offering my own thoughts on a contentious topic in the board game community - hidden, trackable information.

First, let's define the topic for anyone who hasn't heard about it - hidden, trackable information is any information that could be derived entirely using events that occurred publicly for all players, but is kept secret. For example, in Stefan Feld's game Notre Dame, points are earned over the course of the game, and it's always public when you earn points, but you receive them in the form of chips that you keep face down, obscuring their values. So at any point in a game of Notre Dame, you could know each player's score if you have a perfect memory, but you are not likely to.

There are a few arguments for concealing this kind of information - some games play better when certain information is more unknown (for example, in an auction there may be more tension if each player doesn't know the other player's available money to bid with), and so the designers would argue that it's better to leave that information hidden. In some of these cases, tracking the information would be impractical, so the fact that it's technically publicly available to players makes no difference.

Another frequent occasion where trackable information is kept hidden is in scoring. Games that hand out points as they're scored will occasionally keep those totals hidden, either to prevent players from excessively targeting the leader (in a game with more direct interaction), to create more of a sense of suspense when final scores are revealed, or to prevent players who are losing miserably from finding out and being disheartened mid-game.

Opponents of hidden trackable information only have one main argument, but it's a convincing one - since players can track the information, making it hidden creates an obligation to track the information for any player who wants to do well. It's almost a prisoner's dilemna situation - for example, in Reiner Knizia's classic Tigris and Euphrates, you collect cubes of various colors which will directly determine the winner at the end of the game (and your actions may affect which cubes other players are able to get), and those cubes are acquired publicly but kept secret behind a screen. So maybe Tigris and Euphrates plays best if no one tracks which player has which cubes, but if any given player starts tracking cubes, that player will out-perform the other players, putting pressure on those players to adopt this technique as well. People opposed to hidden trackable information thus argue that keeping that information hidden forces players to spend more time remembering minor details and less time on strategy, while disproportionately rewarding players who have stronger memories.

Some games will go out of their way to restrict information and increase the relevance of memory (for example, in Dominion you're not even allowed to look through your own discard pile), while others will actively try to reduce the burden of memory (for example, in Altiplano, you have a bag of tokens, and tokens are put into your discard bin as you use them. You're explicitly allowed to look through the contents of your bag at any time, since you could derive those from your bin, your board, and the tokens you acquired this game)

I would personally lump games with hidden trackable information into 3 categories:

Games in which the only information which is hidden are victory points always seem silly to me. I understand the arguments for hiding victory points, but the increased fiddliness (Puerto Rico, Five Tribes, Notre Dame, and Carpe Diem are all games that would play much more smoothly if they used a simple point tracker on the board rather than chips or cards to track current point totals) is not at all worth the benefit. The only time I think hiding pure victory points could be worth it is in a heavily interactive game where early points may not mean much towards victory, to prevent an early leader from being excessively targeted by inexperienced players. If fiddliness of components weren't an issue though, I would have no problem with the victory points remaining hidden.

On the flip side, there are certain games where I think hidden trackable information is not a problem at all, and these largely consist of games where the information that is hidden is personal information about other players' cards/tokens/etc. For example, technically your hand in Concordia is trackable, since everyone starts with the same hand and all cards are publicly acquired, but it would feel very strange if you had to reveal your remaining cards on request. I think the key here is that the information feels like it 'should' be private in some vague sense of the word, but just happens to be publicly trackable, and also that it rarely heavily affects strategy. Not many other games fall in this category, since most of the time cards are acquired through some hidden mechanism and other resources are both collected and displayed publicly.

When it comes to tracking your own personal information (like Dominion, where you can't look at your discard pile) - I come down neutrally. It's frustrating that optimal play might require remembering something that you could easily have remembered or written down if you'd been focusing on it, but I can understand how certain players would spend too much time processing that information. My solution for this and similar games are to play them on the understanding that you can look through your discard pile, but only when it is hugely impactful to your strategy and quick to analyze (like if you can't remember whether you've bought a certain action or not and are making a decision of which card to buy)

The final, most challenging category are games where hidden information is publicly trackable but vitally important to the game's outcome. 2 big examples of this are Keyflower and Tigris and Euphrates. In Keyflower, you have workers of 4 different colors concealed behind a screen, which you use to participate in auctions and take various actions. Only workers of the same color can be used to raise a bid in an auction, so it is incredibly powerful to know which workers your opponents have remaining. Outside of your starting workers and an occasional special tile, every worker you acquire in the game comes from a visible spot. So both Keyflower and Tigris and Euphrates are in a tricky spot - there are pieces of information that would enable you to make much better decisions, and those pieces of information were publicly available. At the same time, I think most players of both games would agree that each game is better when players do not have access to that information and instead just have a vague sense of "my opponent has a lot of blue workers". In games like these, I think there are 2 choices:

1) Play with a social contract (either formalized or unspoken) that none of the players will actively try to memorize that information.

2) Agree to ignore the game rules and play with that information fully public. Any option in between forces players to either do something unfun or be at a severe disadvantage. As a designer, this third category is something you should be very wary of.

That's my thoughts on hidden trackable information, when it's good and bad and how social contracts can work around it.

0 notes

Text

In Our Darkest Sour Song Origins

Continuing the earlier series of posts, I thought I’d post about each of the songs on our second release, the EP In Our Darkest Sour.

Aryan Girls: I asked Mia to write lyrics for a new song on our EP, to keep mixing things up, and she came up with the main lyrics for the verses as well as the song concept, tying societal anxiety to a more ominous broader threat. I like how it works as a song both about internal feelings on inferiority as well as a topical political concern, and I added on my little pseudo-rap bridge to put a clear political button on it. Musically, I suggested we try again to make a danceable song as Thirst had wound up a good song, but certainly not particularly groovy, and I think this time we succeeded. Both lyrically and musically we’re both very happy with where this ended up.

Jeannette Rankin 2020: This one started with one of Mia’s awesome riffs - pretty much everything about the bass part, including the intro/verse/bridge, was fully formed when she showed it to me and I came up with a drum part. Lyrically, Jeannette Rankin is a fascinating woman who’s always been an inspiration to me - she’s the first congresswoman ever elected, but also has the honor of being the only woman to vote against the United States’ participation in both World War 1 and World War 2. I don’t necessarily personally agree with staying out of World War 2 specifically, but there’s no denying that Jeannette took a bold, unpopular stand purely driven by what she felt was right. For this song, I wanted the spotlight to be on those 2 anti-war votes (there’s certainly plenty else going on in Jeanette’s career, but in particular I wanted to emphasize that this isn’t just somebody who’s a historical footnote because of their gender, but a person who made bold, conscience-driven decisions and would be worth remembering for that if nothing else), so each verse gives some historical background on the WW1 and WW2 vote specifically. Then to keep the song from being too Schoolhouse Rock-y, I wanted the chorus to get more emotional and direct - I switched it to 1st person from Jeanette’s perspective as she made the decisions, while working as many direct quotes by her as would feel natural into the lyric. This is another favorite of ours.

Children’s Crusade: We started this one with a cool drum beat I had thought up, jamming on it to elaborate and make it the dark, dirgey sound it has. The children’s crusades are a truly bizarre, fascinating piece of history, with multiple parallels to modern politics both in the role of religion and in how easy it is for someone charismatic to swindle people into doing foolish things, so the lyrics wrote themselves.

Harper’s Ferry: Harper’s Ferry was the last song written for the EP - at this point, we realized that the first 3 songs all had a historical theme to them, so if we added a 4th, we’d have a concept album on our hands. Having written about Jeanette Rankin, it seemed natural to write a song about another of my historical idols, John Brown. John Brown was an abolitionist right before the Civil War who led an unsuccessful (and to be fair, somewhat foolhardy) attempt to start a rebellion and free a large number of slaves at Harper’s Ferry, WV. The lyrics flowed pretty naturally, with the verses being told from John Brown’s perspective during the raid and the chorus quoting him to generalize his life to all conflicts where the situation has gotten so bad that only extreme measures will suffice. I believe the instruments followed the song concept, if not the lyrics themselves - I set Mia with the vague idea of “let’s make something kind of in the vein of Foo Fighters with a big chorus”, and we created the parts from there.

0 notes

Text

3 Games I Didn’t Like With Mechanics I Did

For my post today, I thought I’d take a look at a few games that I no longer own and talk about a mechanic from each that I enjoyed (despite possibly not enjoying the rest of the game). These particular 3 are all very solid games, and while I ended up selling each of them, they each had a mechanic I thought it would be interesting to spotlight.

Eminent Domain: Deckbuilding with specialization based on action choice

In Eminent Domain, you have several choices of primary action that you can take on your turn, such as drawing more planets to settle or researching a new technology card, and you can enhance those actions by playing cards with matching symbols from your hand. The twist? When you perform the action, you take a card from the middle that has that action and permanently add it to your deck, the end result being that over time, the more frequently you perform an action, the more specialized in that action your deck becomes. This provides both opportunity and challenge - you can make your deck more focused in an area, but at the same time you have to carefully balance your actions to prevent your deck from becoming too focused in an area that won’t help it late game. A great example of an easy to explain mechanic that adds a good deal of depth.

Evolution: A game whose mechanics perfectly reflect its theme

In Evolution, each player is creating and managing several species of animals, each of which can be given various traits such as a long neck that lets them take food first from a common supply, a fat supply that lets them store excess food from a bountiful turn to use on a more limited turn, and even carnivorism that makes them feed on other creatures instead of the common supply. The object of the game is to collect the most food overall. The result is a hyper-accelerated version of the natural selection process; when there is a lot of food, players will be increasing the size of their creatures in order to scoop up as much of the supply as possible, and no one will invest in defensive traits. When food becomes more limited, players will instead invest in traits that let them compete for food, or turn to carnivorism, and once anyone creates a carnivore, defensive traits become of high value (as do offensive traits for the carnivore). The choices of the players really feel like a reaction to the state created by the world, and while not my favorite game, Evolution would have to rate as the game I would call most thematic.

Civilization - A New Dawn: Powerups with unique abilities + Action selection

There are two different elements I’d like to spotlight in Civilization: A New Dawn, a quirky, complex civilization building game. The first is the action selection mechanism, which is pretty unique and definitely very interesting to manage. There are 5 core actions in the game, each of which can be performed at a level 1-5 strength, and you have them in ordered 1-5 slots in your personal player area. On your turn, you can pick any of those actions, perform it at a strength relative to which slot it’s in, and then it goes all the way down to the 1 slot, pushing all the actions it was in front of up a slot. The end result is an action system that rewards diversification of strategy but still offers you a lot of freedom of choice - you can take a 5 strength action every turn, but it might not be the ideal action you’re looking for, or, if you need a particular action, you can take that action more frequently, but it won’t be reaching the coveted 5 slot and you’ll be doing a weaker version of that action. I hope some other euros steal this system, as I find it to be both clear to understand and fun to play with - it gives a great mix of planning ahead (”Okay, if I take a level 4 warfare this turn, it’ll move up my technology action just enough so that next turn, I can unlock my next tech card” and satisfaction when pulling off a big action.

The other element I’d like to compliment is the abilities you can unlock throughout the game. There are a huge number of upgrades and new abilities you can earn in Civilization, from upgrading your tech cards, building wonders, and getting special trade powers from interacting with neutral cities on the map. The crazy thing is, unlike many euros, the vast majority of these are not numerical upgrades but actually grant you new functionality or let you break the rules of the game in some way. I’m always very impressed when a more traditional, strategic game plays in this kind of space, as when it’s done well it can add a huge amount of fun, variety, and replayability to a game. I think Voyages of Marco Polo pulls off a similar trick with its variable player powers, each of which feels huge and gamebreaking while not actually disrupting the balance of the core game.

0 notes

Text

2019 best-ofs!

Hello everyone! It’s the end of the year so I thought I’d post some best-of lists.

Best board games purchased in 2019:

1. Argent the Consortium (Truly a deep, intricate masterpiece that has a ton going on, but still packs a lot more of an interactive gut punch than many similarly complex strategy games)

2. Tiny Towns (The polar opposite - a perfect 30-minute game that's easy to pick up, addictive, and repeatable)

3. Altiplano (A great, quintessential euro with simple mechanics but deep strategy)

4. Ganz Schon Clever (Another light game that packs a good amount of tricky decision making into a < 30 minute game on a colorful sheet)

5. Keyflower (So many interesting layers to this game! Glad I tried it out to confirm that the 2 player mode does indeed play well)

Best board games released in 2019:

1. Tiny Towns (see above - I love how the rules are so simple but the constraints end up getting so challenging during gameplay)

2. Cartographers (A great roll-and-write with some nice twists and a fun scoring system)

3. Tapestry (Not a game I’m interested in buying because of the overproduction and luck factor, but I definitely enjoyed playing this and there’s some interesting combos to set up)

4. Hadara (A nice light, accessible strategy game - fills a similar space to 7 Wonders)

5. Revolution of 1828 (Great vicious 2 player game that plays pretty fast)

Best concerts I attended in 2019:

1. System of a Down at Open Air 2019 (these top 2 were both bands that had been on my must-see list for a long time, so they had an easy edge, but neither disappointed! We stood a little further back at SOAD so we can jump around and dance like maniacs, and they lived up to that expectation with a 20+ song classic-filled set)

2. Television at Maurer Hall (Television are living legends to me, and they played almost all of the classics of Marquee Moon, so this was utterly fabulous.)

3. The B-52s at Riot Fest (Pretty sure I have to put these guys on here, given how many comparisons Lemon Knife get to them - but this was in all seriousness a fantastic, fun, danceable show!)

4. Bloc Party at Riot Fest (Bloc Party were performing Silent Alarm in full, and as it’s one of my favorite, most consistent albums, this was a terrific show - another one where I jumped around like a lunatic.)

5. Iron Maiden at Tinley Park (Cinematic and skillful - Bruce Dickinson’s voice has barely lost a thing since the classic albums were recorded.)

Best songs showing long-established artists could still make great music in 2019:

1. Vampire Weekend - Harmony Hall (I still haven’t listened to whatever Old Town Road is supposed to be - this to me is the song of the summer)

2. The Hold Steady - Entitlement Crew

3. Frank Turner - The Graveyard of the Outcast Dead (Frank released an interesting concept album where every song told a story about a woman from history - I really didn’t like his previous album Be More Kind but he seems to have his mojo back here! Graveyard of the Outcast Dead is a passionate, epic song that manages to be a Christmas song while being sung from the sympathetic perspective of a dead prostitute - it’s my pick from the album)

4. Muse - Pressure

5. New Pornographers - Colossus of Rhodes

Best movies released in 2019 (I only saw 5 movies this year, so I’ll just put a top 3 - the top 3 were certainly excellent!):

1. Parasite (Such a weird mix of genres, but just generally an amazingly-written, unpredictable movie)

2. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (Near the bottom of Tarantino movies for me, but that still means it's a fantastic film full of great performances)

3. Knives Out (I thought this would have more of a meta-twist level than it ended up having, but still well-written, well-acted, and just generally a lot of fun.)

If you have any thoughts of your own for any of these categories, post them in the comments!

0 notes

Text

I Know That This Is Vitriol!

Hi all, this week marks another exciting creative release for me, as my band Lemon Knife’s second full-length album came out on Monday! You can find it on lemonknife.bandcamp.com, stream it at https://open.spotify.com/album/23dO6hen0Nx0FiaVqxWlCI, or hear it anywhere you find music online. I thought I’d write this week’s post talking about the album and some of the inspirations and themes on it.

Let’s start with the title - after we had a few songs together for the album I knew that it was going to be a more political album and certainly one that still had a dark tone. Our debut, Songs About Water and Death, was also somewhat dark, but while it had some political songs it had more of an introspective feel; our EP In Our Darkest Sour was political but through more of a historical lens. IKTTIV is more direct, and also is written with something more like a call to action in mind, on songs like Thunder Owed and You Can’t Shrug Your Way to Valhalla. I didn’t want to just complain about how things are but rather also encourage people to take action. So the title itself is a quote from R.E.M.’s anti-Reagan classic Ignoreland: “I know that this is vitriol, no solution, spleen venting...but I feel better having screamed, don’t you?” My intent is that this is a big climactic venting of political and societal frustration, and that our next album might switch tacks a little, possibly musically but definitely lyrically. (Hopefully our next album’s release will also see slightly less frustrating leaders in charge, of course)

The songs themselves were written throughout 2019 - Thunder Owed was the first wholly new song we wrote for the new album around the start of the year, while Whaler’s Widow and The Day We Took Our Country Back were the last couple written and recorded towards the end of November. We’ve got a wide range of songs on this album - we definitely experimented with some different sounds, from the soft-loud 90s style of I Will Remember (which was also a lyrical challenge to myself - I wanted to see if I could write a good set of lyrics without my typical wordiness) to the almost dancey, repetitive groove of Whaler’s Widow or the dramatic temposhift in Endless City. The songs were all recorded and produced by CJ Johnson, who we’ve worked with on all of our releases so far - we love his no-nonsense, productive studio approach and he has a knack for finding great effects to add to the bass and vocals.

A few notes on individual songs:

Dirty Life and Times of a Gun: I never get sick of listening to this song - this is one where we started with the lyrics and built a song around them. I was inspired by Murder by Death’s style (they also get a song title shoutout elsewhere on the album!) to try and write a murder ballad, and then to add a twist I left the ending unknown. Mia was in turn inspired by the western theme to add a slide to her bass, giving this one a really fresh feel. We both loved it enough to make it the lead track.

Vultures: Probably my favorite song on the album to play on drums - this one is a real killer live!

The Old Bastard Will Be Missed: This was actually written in the very early days of Lemon Knife, but only the first half - I liked the concept but the song itself was a little lacking. We decided to revisit this and add a second half to make it a little more fleshed out, and the result was interesting enough to keep!

Broken Ankle, Broken Mind: Mia wrote the lyrics here, and they’re great - it’s awesome to see her pushing some new lyrical frontier and tackling something really controversial and direct that means a lot to her.

Whaler’s Widow: This is our 2nd or 3rd attempt to make a song people can dance to - I’m still not sure if it fully succeeded at that, but I love Mia’s vocal melody and delivery on the finale.

Thanks for reading, and be sure to give the album a listen - we’re quite proud with how the songs turned out! Next post I’ll be back with the year in review.

0 notes

Text

Rock Band: Something I’m thankful for

In keeping with the theme of Thanksgiving week, I thought I would give a shout out to a video game franchise that’s had an enormous positive influence on my life and my hobbies, that being Harmonix’s Guitar Hero/Rock Band series of games.

When I was 14 or 15, I got Guitar Hero 2 for my birthday and immediately fell in love with it. I played through the entire game on easy, then medium, then hard, then expert, struggling at each new difficulty level and often getting stuck on specific songs, but ultimately beating the entire game and 5 starring the vast majority of the songs on expert. They had a remarkable variety of music from all decades and subgenres of rock, and as someone who hadn’t listened to much outside his parents’ collection of 60s CDs (all of which do still hold up as great) they exposed me to a very wide range of new artists and songs to fall in love with, and began my habit of having a pretty broad, eclectic taste in artists.

2 or 3 games later, Rock Band came along, and when I got the drums, a whole new world opened. I loved the physicality of them, and I loved the sense of accomplishment that came from how close they were to the real instrument. I also loved the brand new learning curve - hand and foot separation was an entirely fresh challenge that took quite a while to master but paid off when I did. By pure coincidence, my grandparents happened to be moving to a smaller house around this time, and asked my parents if I might want their drum kit - so now there was an actual kit to make mayhem on too! I began by playing along to songs I had learned in Rock Band, or sometimes even while watching a Rock Band chart, but within a year or two I had moved up to rocking out to anything in my headphones and making random weird projects (that sounded about as good as you’d expect a project with just drums and melody-free vocals to sound)

Throughout college and the years immediately following, I never joined a band - I was too busy in college, and too worried about not owning a drum kit or car with me in Chicago in the years afterwards. But through it all, while I would practice on a real kit about once a week, I was still playing hours of Rock Band drums and staying sharp. Finally, after I met my girlfriend Mia and formed Lemon Knife with her, we’ll still play it for fun, and I’ll still use it to warm up if it’s been a little while since actually drumming and I’ve got a gig the next day.

So this post goes out as a big thank you to Harmonix for making such an awesome, skill-teaching game that’s had a definitive, positive impact on my life.

As some additional content, here’s some thoughts on why the design of Rock Band appeals to me so much as a gamer, and some thoughts as a drummer on what the biggest differences are between Rock Band drums and actual drums.

In terms of design, I think the key gameplay element of Rock Band (and most similar rhythm games), in addition to the physicality and the music, is that each challenge is designed to lead to a great curve of mastery. You play the game as a series of songs, each of which:

- Is generally less than 5 minutes long, so if you have to restart and try a song multiple times, it’s not a huge frustration point.

- Can be replayed at will. In addition, most of the games will let you go into a practice mode and practice specific sections of a song.

- Has a variety of levels of success beyond a simple Yes/No (if you’re trying to beat the song, you can make it farther; if you’re trying to 5 star the song, you can keep track of your score and how it’s improving even before hitting the 5 star mark)

- Is fair and unchanging. There are no random, punishing elements, but equally important, there are no catchup elements. If you play the same song twice, and you get 150,000 points the first time and 200,000 points the second time, you unequivocally did better the second time. If you fail a song 10 times in a row, you won’t get any extra powerups the 11th time you play it - you’ve got to beat it for real.

Those 4 key elements make it particularly engaging, as they mean that success and failure are a real matter of practice and experience, practice and experience that the game lets you get by replaying a song as often as you like, so that when you succeed, it feels like pure accomplishment. I look for those in other genres of game as well (I particularly can’t stand many mobile games for this reason - a lot of them have catchup mechanics to keep players hooked that take away the core challenge. If I know that I just beat a level because the game lowered the difficulty, there’s no satisfaction in it for me).

Finally, here’s the biggest differences between Rock Band drumming and real drumming, beyond the obvious (like plastic toy vs loud noise-making thing):

1. Your left foot is not used in Rock Band, while on actual drums it gets used to open and close the hi-hat and make hi-hat clamping noises (I’m sure there’s an actual term for these) or for double bass in metal.

2. Dynamics don’t matter in Rock Band - however you hit the drums is okay, as long as you hit the right ones. On actual drums though, a lot of variety in the sound, especially on songs with a mix of volume levels, comes from dynamics, and you can’t just barely graze the right drums and produce anything sounding good. There are even a lot of beats that rely on accented notes for their structure.

3. Related to dynamics, while actually drumming you may need to grab cymbals to silence their ringing and get a less sustained tone.

4. Finally, a big one is that in Rock Band, the parts are all there, waiting to be played, while on actual drums you have to come up with a beat, fills, and variations yourself.

Bit of a rambling post here, but all variations on a theme - hope you enjoyed it! Next time, I’ll be talking about Lemon Knife’s upcoming record, I Know That This Is Vitriol.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Evolution of a Game: Mint Condition Comics

My first published game, Mint Condition Comics, is coming to now live on Kickstarter on Monday, November 11th, and I’m super excited about it! You can back it here: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/miguelthedesigner/mint-condition-comics-a-neat-game-about-comic-books

I thought today I would talk about how the game evolved, going through many stages to get to the (in my humble opinion) awesome light but thinky game it is today.

Stage 1: Idea

Some games evolve gradually out of existing concepts or thematic overviews, while others basically have a singular lightbulb moment. Mint Condition has evolved a lot, but the core idea sprung fully formed from my head while going for a lunchtime walk along the Chicago Riverwalk one sunny day in August 2018. A lot of games play with drafting as a mechanism, but those games tend to not support 2 player play (7 Wonders), not be good at 2 players (Sushi Go), or be good at 2 players in spite of their drafting rather than because of it (Seasons). However, the issue of drafting at low player counts has already been thought about at length in the Magic:the Gathering world, and one solution immediately popped to mind - Winston Draft, where there are 3 piles of facedown cards and you iterate through them, looking at each pile and then either taking it as your choice for the turn and replacing it, or moving to the next pile and adding another card to sweeten the pile you passed on. Winston Draft adapts drafting to a format that can work at 2-3 players and has a nice unknown tension to it. So the initial germ of an idea was “I’ll try and make a drafting game that works for a smaller player count by making Winston Drafting the primary drafting mechanism.”

Stage 2: Rough Prototype

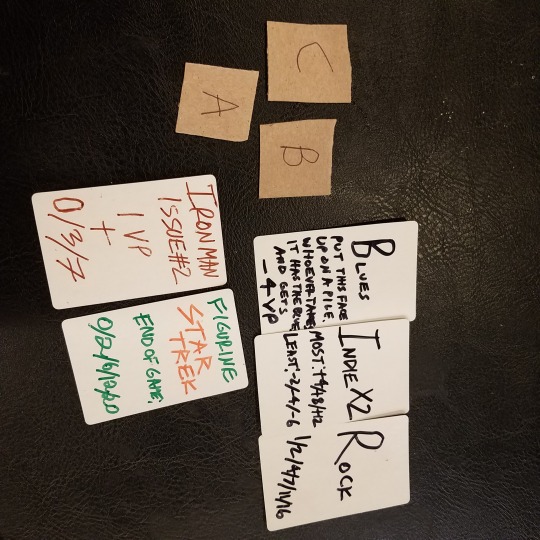

And when I say rough, I mean rough. I’m very much a mechanic-first, theme-later designer, so my first prototype that I brought to my design group was a plastic bag full of cardboard scraps with single letters scribbled on them. At that stage, there were 4 or 5 types of letters - A, B, and C which scored you more the more of them you had (A being the highest scoring but the rarest), D which scored only for the player with the most (like Sushi Go’s Maki), and E which you kept between rounds and which would score a lot if you could collect several of them over the course of the game (the idea being that you could go for a long-term strategy hoarding E’s.) It wasn’t pretty, but it conveyed the core idea of the game, and generated enough enthusiasm that I continued to iterate on it.

Stage 2: Slightly-less Rough Prototype

The game next briefly went through a phase where the above letters were converted to ancient history things like gold/silver/bronze, and there was a fire tile that penalized the player with the least fire at the end of each round. There was also temporarily a mechanic where players could keep 1 or 2 cards from each round to the next, to give players more of an ability to focus on a long-term strategy. I pretty quickly transitioned over to record collecting as a theme, and upgraded my components to blank cards with permanent marker, also adding in a few bonus cards that messed with the draft in minor ways.

Stage 3: Comics!

Throughout this process, Miguel and Aaron from neat games were part of my design test group and were going through the process of publishing their first release as Neat Games, Too Many Poops. It was a light card-based game, much like my game Record Rampage, and so we discussed them publishing it after Too Many Poops finished. During this part of the process, based on potential customer feedback, we decided to retheme to comic books to have a more accessible theme, while the mechanics were also undergoing some minor tweaks, the biggest one being the addition of a market where players could trade up a few lower comics for a more valuable one, or trade a more valuable one for a few lower comics, giving more flexibility to players. Along with the transition to comics, a shift was made where instead of sets all being the same size but rarer sets being more valuable, sets varied in size, with a set with 6 elements being harder to complete than a set with 4 elements but worth more if you could get to 6, and the individual elements were given varying rarities along with a small point bonus simply for having the rarest elements, to add a little more inherent value to some items during the draft (Issue #1s and #2s, thematically enough)

Stage 4: Balance Overhaul

Around January 2019, I was getting some feedback about decisions being not quite interesting enough, and I was also noticing that the correct decision most of the time was to take the biggest pile, because the points from lots of little 1-2 size sets would add up quickly. Thus, I made the biggest balance change I had made in quite a while since early on in the process, sharply cutting the points for low #s of issues while raising the payoff for complete sets, removing inherent points from Issue #2s, and adding personal missions to complete for bonus points (like “Collect 2 or more sets of Superman” or “Have the fewest comics”) and personal 1-use special powers to add a little more spice. This temporarily broke the game, but ultimately got it to a much more satisfying place, moving it down the local maximum hill and towards the global maximum mountain. Starting at this point, art began to be commissioned for the game and all the other spinning wheels of development continued to turn.

Stage 5: Final Tweaks

The last 2 major changes to the game came in late spring/early summer 2019; one of which was converting personal missions to 2 separate sets of global goals - a comic chosen each round to award bonus points to whoever had the most of it, and a separate goal like having the fewest comics overall. Around this time, we faced a dilemna - many people who played the game wanted a trading mechanic, but we were all in agreement that a trading mechanic would slow down the game significantly and harm the balance (a lot of times in a game like this, a trading mechanic not only puts an enormous amount of focus on social and trading skills over any other skills, but also makes the draft incredibly uninteresting - if you know that someone will trade for any super-rare card, the best move is just to always take the rarest card(s) regardless of what your strategy is) However, we did want a little more player interaction in the game and a little more player agency over the results. We tried a ‘trade zone’ (you could put 1 comic in your trade zone on your turn, and any player on their turn could trade at even rarity for your trade zone), which solved the slow down problem but not the other problems, and added significant rules overhead, before stumbling upon a solution that worked out perfectly - allow players to trade directly with other players (whether or not that player agrees) but only for the same rarity and only for comics not part of any set. This way, there’s no negotiation, but it’s usually not a hostile move, as there’s rarely reason for a player to be attached to a loose comic that’s worth 0 points.

This final touch added the last little bit of interaction and control that the game needed, and all these changes were really a testament to the quality that our lengthy development process and our strong team of me + Miguel + Aaron added to the game design and balance. I think Mint Condition Comics started out with a very solid design and core idea but ended as an even better, much more satisfying game, with none of the design vision compromised.

Stage 6: Release

After early summer, there were a few small tweaks, but the remaining development time was largely dedicated to neat games hunting down artists to pull off the remarkable stylistic diversity and artistic quality that they wanted to bring to the illustrations on the different comic series. And now, here it is, live on a Kickstarter near you! Again, I’d encourage you to definitely take a look if you like comic books or just light card games that scale well to a wide variety of player counts: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/miguelthedesigner/mint-condition-comics-a-neat-game-about-comic-books

0 notes

Text

Songs About Water and Death song origins, pt. 2

Made it Out Alive:

This song started as a jam in the practice space on a riff structure Mia had created, I think inspired by early-2000s rock like Jet and the Strokes. Lyrically, I wanted to write something with a sense of humor, since we had quite a few bleak songs on the album and plenty more dark ones; the riff and beat had a pretty upbeat feel so it fit atmospherically. Once I had the basic idea, it was just a matter of coming up with as many ludicrous rhymes as possible - finally, at the end, I decided to add a serious ending to give a tiny bit more weight to the song.

Thirst:

We sat down to figure out the music that would become Thirst together, and I had an idea to write something a little more dancey, a well that I would go back to some more on our later songs, so this song started with the drumbeat and built up from there. I think there are some later songs that pull off ‘dancey’ more cleanly - this one always feels more like a Nine Inch Nails-style doom march, but nothing wrong with that. Lyrically, I set myself the assignment of writing a song from the perspective of Hillary Clinton - I was not a big fan of her following the 2016 primary so I thought it would be a nice challenge to get inside her mind during the contest.

Man of Glass:

I believe this one also started with the drum beat and was built up from there with that nice crunchy Sonic Youthy riff. Lyrically, I was experimenting with writing a fairytale story, the kind you could find in a kids book of legends. Not too much to say here.

Girl With the Cat Eyes

How to tell we are not Rush in one easy step: this is the only song on Songs About Water and Death in a time signature other than 4/4. Girl With The Cat Eyes actually had its origin several years ago, when I was living in Pittsburgh. One day while out walking, I randomly had the idea - what if you found out that a distant acquaintance of yours had gone missing or been found dead, and the last thing they wrote was something dedicated to you and addressing you as “The Guy With the Face”? It was the double mystery - why were you so important to this distant stranger that you were the last thing they wrote about, and what does “The Guy With the Face” even mean? I brought this idea to Mia and she liked it, so we set out to write it as one of our rare ballads. “Guy With the Face” was a little goofy, and Mia was going to sing it, so I changed it to “Girl With the Cat Eyes”. This was one of our earliest songs, early enough to make it to our first ever gig in September 2017 but not quite favored enough to make it onto Storms and Snakes.

Red Stage

The name of this one is a direct reference to the Pitchfork Music Festival 2016 stage where Brian Wilson performed Pet Sounds. It was an amazing show, and one I was very glad to witness, but it was also deeply sad - Brian was clearly not in great health, and had to let the other performers take the lead on most of the songs (though when he did sing, it still sounded fantastic). He also wasn’t playing anything, so for most of the set he was just there in the center of the stage sitting in a chair. I felt quite bad for him - here’s this visionary genius, on stage performing his masterpiece, and his body has failed him to the extent that he has to put it in the hands of others. So I turned that into a lyric from his perspective (come for Hillary Clinton’s perspective, stay for Brian Wilson’s perspective!) tied in with some ocean metaphors about wanting to be swept out to sea rather than witness that happen to me (of course, we’ll see how I feel when I get older...) And of course I got a nice little wink in by putting a Beach Boys title to each verse. Instrumentally, we were starting from the song concept, so we tried to make it a less traditional beat and more of a Beach Boys/60s style production, especially in the drums, but filtered through our traditional distortion it makes quite a cool blend. One of my favorites off the album.

1 note

·

View note

Text

There are many people who play Magic: the Gathering as either a casual or competitive hobby, and there are many people similarly who play a great deal of board games, but despite both testing similar areas of strategy, there’s less crossover than you would expect. Magic players are often so invested in the many facets of the game that they would rather play more Magic than play a different game, while board game players see Magic as expensive and inaccessible compared to the games they play. Personally, I’ve played a lot of magic, having continuously played casually since I was 9 and having competitively played once or twice a week for a 2-3 year period in my early 20s. I’ve also played a ton of Euro-style board games over the past decade and developed quite a collection. So I thought it would be interesting to write about Magic from a board gamer’s perspective - how would it hold up if viewed as just another board game? I’ll be writing this assuming you know nothing about Magic aside from a general idea of what a collectible card game is.

First, I’m going to explain why Magic has been so successful and why it has lasting appeal. Second, I’m going to touch on a few of the most notorious negative aspects of the game of Magic, such as the financial cost and the luck factor. Finally, I’m going to list a few accessible ways to play Magic and describe how they would hold up as standalone board games.

Strengths

Magic: The Gathering has continued to release new content several times a year, every year for 26 years, and is currently selling more product than ever. Why has it been so successful? There are a few main answers. For one thing, there’s a great deal of strategic depth in any given game. If playing 1v1, almost every game features a huge number of decision points, any one of which might not matter but the collective whole of which will determine the winner. A multiplayer setting is similar, but adds in significant political elements and dealmaking. Even more importantly, with all those years of content, there’s a massive amount of strategic diversity. Hundreds of thousands of cards have been made, and the vast majority have been designed in an open-ended enough fashion that there are constantly new combinations that can be put together and played with. In addition, any one given 2-player game of Magic will typically last less than half an hour, giving it a big strategic punch in a short length of time. I’ve played more hours of Magic by far than any other game, and it’s precisely because of that incredible depth.

Barriers to Entry

This section is going to ignore things that might dissuade someone from playing competitive Magic in, for example, a store, since it’s beyond the scope of this article. I’m assuming you have a regular group of board game players or regular opponent and you’re wondering if Magic could be a fun experience for you.

Rules Knowledge

Magic has a reputation as a very complex game, which I think is partially deserved and partially undeserved. It is deep to the extent that because of the constant release of new material and the sheer number of decisions encountered in the course of any one turn or any one game, even players who make their living playing Magic frequently find themselves faced with challenging choices. On the other hand, compared to a heavy euro or a wargame, it’s very easy to pick up a starter deck, learn the basic rules of Magic, and play a simple deck at a solid level of skill. I think if you are teaching just the core rules of the game with simple training decks, I would give Magic a weight of about 2.0 on the Boardgamegeek weight scale. On the other hand, if playing a more complicated, full variant, I would increase that weight accordingly, but never going above a 3.0 or so - I think a couple that can handle Twilight Struggle can certainly handle learning Magic at its most intricate. Magic also has a reasonably good depth payoff for its complexity.

Luck Factor

The way you play cards in Magic requires you to draw the correct land cards from your deck. Because of this, if you draw too many land cards and not enough creatures and other spells, you will likely lose, and the reverse is true as well. As a result, even in a 2 player match between an incredibly skilled player and a fairly unskilled player, the unskilled player will have at least a 10-15% winrate. This might be anathema to a euro player where games feature minimal luck and player interaction, and the most skilled player wins 99% of the time, but it is also easy to work around in a non-tournament setting. Encouraging people to redraw their hands until they have a reasonable mix of lands and cards they can play would be infeasible in competitive, tournament play of Magic, but there’s no reason that something like it can’t be used for a group that trust no one’s going to use it to unfair advantage. Alternatively, especially when playing 1v1, it can help to view the game like poker, where any one hand can come down to luck but the overall win percentage never lies.

Financial Cost

Competitive players who enter a ‘Standard’ tournament (playing an optimized deck, but only using cards printed in the last 2 years that are generally relatively cheap) will often have spent $300-500 on their deck, and that isn’t even the most expensive format! Compared to a typical board game costing $40-80 dollars, a cost that only 1 person has to pay, that seems exorbitant - and it is. However, we’ll see in my next section that many of the ways to play will cost much less than this and will more approach the cost of a standard board game.

Ways to Play

I’m going to break down a few accessible ways to play Magic without necessarily needing to compete in a financial arms race - I’ll describe each and explain the cost, complexity, replay value, and preparation needed for each.

Pre-Made Decks

Wizards of the Coast has several lines of products that contain either a pair of decks or a set of several decks, all designed to interact well with each other and lead to a balanced, competitive game. You can buy however many of these as you have players, take them out of the box, and immediately play, either 1v1 or multiplayer.

Cost: $10-$30 per player, depending on the product line.

Complexity: 2.0-2.5, depending on the product line.

Replay value: Medium - you could certainly play many games and have each play out differently, especially with something like the Commander line of products. However, if you only play with your own deck, you may get bored of the specific playstyle of that deck after 5-10 plays, depending on the product.

Preparation needed: Minimal - 1 person needs to pick up a set of the decks and bring them.

Drafting

The way a booster draft works is that 3 booster packs are needed for each player. Much like 7 Wonders, the cards in the packs are drafted (each person is looking at a pack, then everyone simultaneously, secretly picks a card to keep and passes the remaining ones), so with 15 card packs everyone ends up with 45 cards each by the end. They use approximately half of those cards, along with some provided basic lands, to build a 40 card deck, after which you can pair off with various people and play a series of 1v1 games or best-of-3 1v1 matches.

Cost: $10-15 per player per draft.

Complexity: 2.5

Replay value: Low - after an evening of playing with one draft deck, you’re probably going to be ready to move on and draft again, so this can be an expensive form of Magic.

Preparation needed: Minimal - you just need 3 booster packs per player and about 100 basic lands for everyone, which you can buy for $10 or less and re-use each time.

Cube Drafting

The actual gameplay of cube drafting is identical to drafting. However, the biggest difference is that rather than each player opening 3 booster packs, each player forms their ‘booster packs’ by drawing 15 cards from a large common pool of cards (typically, the common pool contains around 360-720 cards). After the entire cube draft is over, all of those cards return to the common pool, so a cube is much more like a traditional board game - only one person needs to own a cube, and it can be replayed over and over unlike a traditional booster draft.

Cost: $100-300 to construct a reasonable, fun cube (there are infinitely many places to spend more money throughout this process of course) This is a total cost, unlike the others which had per-player costs - if you build a 360-card cube this way, it will work for up to 8 people.

Complexity: 2.5-3.0 (a cube will often end up containing a higher frequency of complicated cards with complicated interactions than a booster or premade product will)

Replay value: Very high - even a normal cube can be played over and over, and it’s incredibly easy to swap a small number of cards in or out of the common pool and completely change the player experience.

Preparation needed: A great deal - one person needs to foot the initial expense (or split it), research which cards they want to include, find and purchase all of those cards, and provide basic lands and possibly sleeves (if they have valuable cards they want to protect).

Hopefully this has encouraged some people who might be reluctant to dip their toes into the world of Magic. It’s got some drawbacks, but overall it certainly is an incredibly rewarding and deep game.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Songs About Water and Death song origins, pt. 1

Hello again! I’m continuing my series on the songwriting origins of Lemon Knife songs. Last time, I talked about the 4 songs on our debut EP, Storms and Snakes. Those 4 songs also appeared on our first full-length album, Songs About Water and Death, along with 9 other songs, so today I’m going to look at 4 of those 9 songs and talk about what inspired them and how they were written.

American Desert: This is actually the first John-vocal song we ever recorded as a band. I believe (but am not 100% certain) that I came up with the idea to do a fast, punk song with a repetitive chorus like Nazi Punks Fuck Off by the Dead Kennedys, and then we jammed on it together during practice and came up with the beat and riff together before I wrote lyrics. It probably contains the only time I’ve ever asked Mia to make a specific change to one of her riffs - as the melody master I defer to her, or sometimes if she’s undecided she’ll play a couple riffs and I’ll tell her which one I like best, but on this particular occasion the suggestion of having the 3rd repetition in the guitar pattern go up instead of staying the same as the others was mine. Lyrically, this was also the first angry song I wrote, and there’s plenty of standard anti-Trump stuff in there, along with my desire to proactively go after the working class people who voted for him when he’s planning to take away the health care they need to survive, rather than “just let[ting] [them] die” from said lack of health care. Light-hearted stuff!

Black Site: This one developed off of a killer pair of riffs Mia had written that we rocked out to in practice and developed a structure of a song. My drumming is certainly very Dave Grohl inspired here (just listen to the intro and the intro to Breed...). Lyrically, I was trying a new approach of this one by writing a political song with slightly less direct lyrics, trying a more REM-ish approach. It’s a back and forth dialogue between two characters - in the mid-2000s-setting, my character is new to the CIA and Mia’s character is a veteran agent who tries to teach me the ways of torture. By the end though, I rebel and testify against her, and “We need to make sure this never happens again” shifts meaning from verse 1 to verse 2. I thought it would be fun to play against type-casting and make Mia play the villain here.

Not on Mars: The only guitar song on the album, this one was inspired by a riff Mia came up with when practicing Run Like Hell by Pink Floyd and riffing on the bridge. Lyrically, I tried to mix things up and write shorter but still effective lyrics, going for a Flaming Lips-style (to go with the sound) mix of a little bit of comedy and a little bit of pathos - the narrator misses many things about Earth, starting with mundane, ridiculous items, and eventually getting to the real point of missing his/her love.

A Summer Feast: A Summer Feast started with the drum beat, which I fiddled around with a bit in practice before we wrote a riff to go with it. The vocal melody Mia came up with and the beat had a little bit of a merry jig feel to them, in my mind, so I tried to write lyrics that would paint a scene like that...but with a painful knife twist, of course. Sharks have always been one of my favorite animals, so what better surprise could there be at a party than finding out your hosts were actually ravenous were-sharks?

0 notes

Text

Dominion vs. other deck builders

I’m sure this is a topic other folks have touched on plenty of times, but I thought it would be a fun inaugural game design post here - Dominion basically founded an entire genre of deckbuilding games, where you start with a (typically weak) starter deck and acquire cards through the course of gameplay, often improving the deck along the way. The main point I’m going to be looking at is:

What are some of the specific design choices Dominion made, and which of those have remained in other deckbuilders? How many of those still hold up?

1) Your hand size is a fixed number of cards, and you discard leftover cards at the end of turn before drawing back up to that hand size.

This has remained consistent throughout many deckbuilders - it provides a clear structure while keeping individual turns relatively simple, since you just have to make the most of each hand of cards you draw.

Occasionally, you have the option to keep leftover cards instead of discarding them - this can provide much greater player control and reduce frustrating “almost there” hands, at the cost of requiring a lot more forethought and decision. One game where it works excellently is Great Western Trail, where your hand has a value that will be used only after several turns (when Kansas City is reached), so by making the hand persist from turn to turn, the player can build up towards a goal before reaching Kansas City.

2) You are limited to 1 action per turn, and 1 buy per turn.

Covering the “1 buy per turn” first, I think most deck-builders post-Dominion have gotten rid of this restriction - it rarely comes up in Dominion or rarely would come up in other games, since more expensive cards are often exponentially more powerful than cheap cards, and the few times it does come up are usually to stop someone from pulling off an interesting trick.

I’m not a huge fan of the action restriction either, though there are a few advantages:

It can require players to purchase a combination of cards (instead of just buying cards that let you draw more cards, you might need to buy those alongside cards that give you extra actions)

It can make players make difficult decisions on any given hand.

It allows you to make actions more powerful than they would be otherwise, and also gives another lever that can be used to adjust the power of individual cards.

The biggest downside is that it reduces the player’s ability to use the interesting cards. A lot of times, I’ll take a look at several 3-cost actions available for purchase in Dominion, and realize that just getting a Silver (a basic treasure card) would be better. It’s good for that to occasionally be the case in your game, but when it’s the case as often as Dominion, more games are going to feel the same. The bulk of players’ decks are already basic starting cards - when the best strategy is only to purchase 1-2 action cards over the course of the whole game, everyone’s decks feel very similar and everyone’s turns are uninteresting as they just play basic treasure cards. Personally, while I think it would be hard to unhook the 1-action limitation from Dominion, I never miss it when playing a more recent game that has moved away from the restriction (which most have).

3) A fixed set of cards are available each game