Text

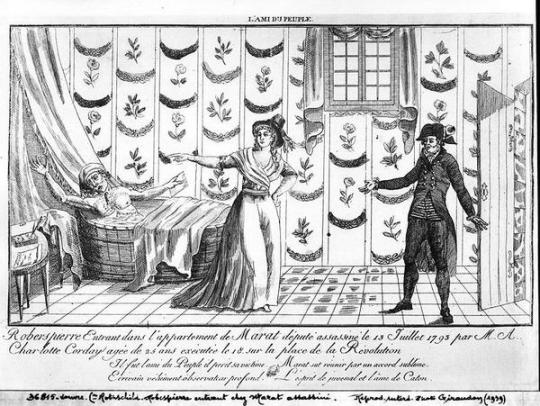

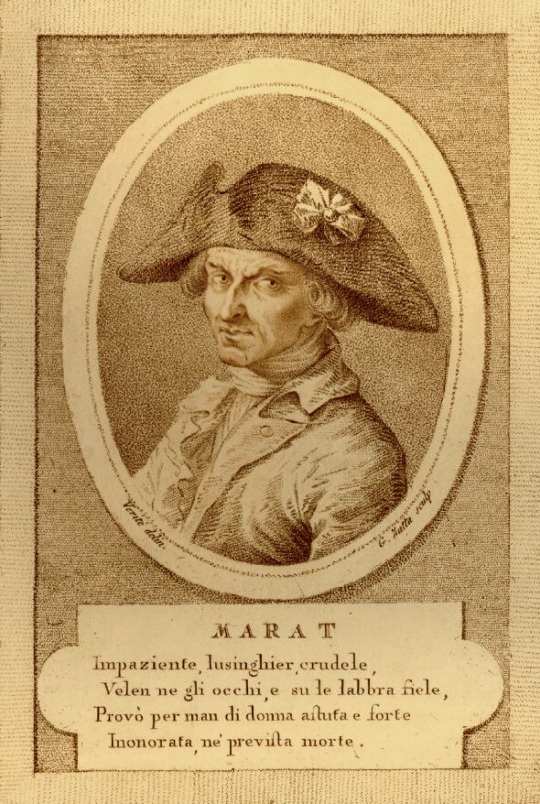

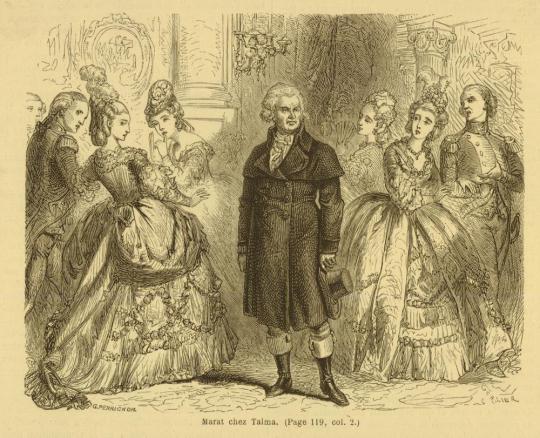

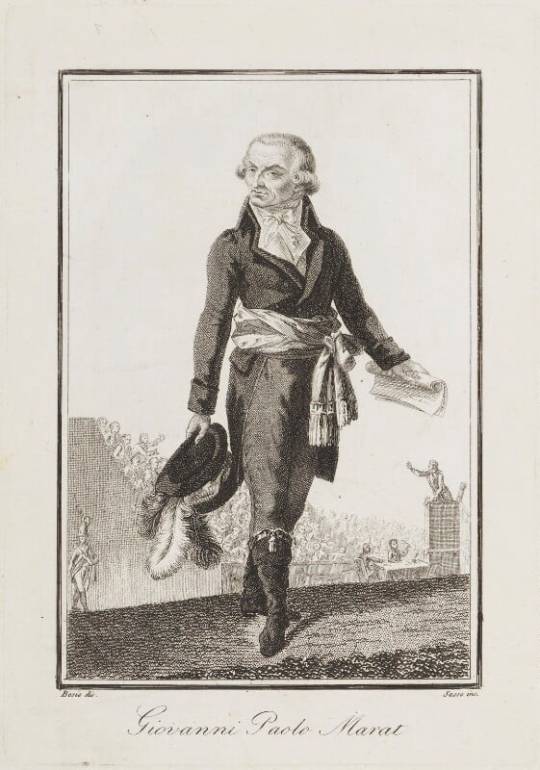

Curiously, there are, in fact, a number of interesting representations and engravings of Marat in which he is wearing a wig. Unfortunately, I don't recall seeing anyone actually talk about this aspect, but it is clear that in most of the physical descriptions made by Marat's contemporaries, no wig is mentioned, which leads us to the fatal question: did Marat really wear a wig? Could these engravings, perhaps because they were not contemporary with him or because they were produced by artists who never actually saw Marat, have depicted him wearing a wig simply because this was common among politicians at the time? In particular, although the idea of Marat wearing a wig is completely foreign to me, I believe that he must have worn one at some point - perhaps in the pre-revolutionary period, when he was somewhat involved in some social circles of a more noble and aristocratic nature due to his activity as a doctor? - only a few times, which I don't think is impossible. Even so, given the vast majority of paintings and descriptions we have of him without wigs, I think we can consider that they weren't a big part of Marat's conventional style. So here's a brief compilation of some of the wigged Marats I have:

I've never seen Marat with a wig.

I was surprised because I had imagined (without any evidence) that he refused to wear a wig for political reasons. (I'm not sure how much of this picture is based on historical reality).

Since I learned about them, I've always wondered why Robespierre and Danton wore wigs while Marat, Camille, and Saint-Just did not. (Maybe they also wore wigs sometimes and just wanted to be painted without them in their portraits, but even if so, the choice is interesting).

And I would like to see Robespierre and Danton without their wigs (not before their executions). I guess Constance Charpentier (Danton's sister-in-law) would have left some sketches of him... (also without any proof)

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robespierre on Property (24 April 1793)

First, I shall propose to you a few articles that are necessary to complete your theory on property; and do not let this word “property” alarm anyone. Mean spirits, you whose only measure of value is gold, I have no desire to touch your treasures, however impure may have been the source of them. You must know that the agrarian law, of which there has been so much talk, is only a bogey created by rogues to frighten fools. I can hardly believe that it took a revolution to teach the world that extreme disparities in wealth lie at the root of many ills and crimes, but we are not the less convinced that the realization of an equality of fortunes is a visionary’s dream. For myself, I think it to be less necessary to private happiness than to the public welfare. It is far more a question of lending dignity to poverty than of making war on wealth. Fabricius’ cottage has no need to envy the palace of Crassus. I would as gladly be one of the sons of Aristides, reared in the Prytaneum at the cost of the Republic, than to be the heir presumptive of Xerxes, born in the filth of courts and destined to occupy a throne draped in the degradation of the peoples and dazzling against the public misery.

Let us then in good faith pose the principles that govern the rights of property; it is all the more necessary to do so because there are none that human prejudice and vice have so consistently sought to shroud in mystery.

Ask that merchant in human flesh what property is. He will tell you, pointing to the long bier that he calls a ship and in which he has herded and shackled men who still appear to be alive: “Those are my property; I bought them at so much a head.” Question that nobleman, who has lands and ships or who thinks that the world has been turned upside down since he has had none, and he will give you a similar view of property.

Question the august members of the Capetian dynasty. They will tell you that the most sacred of all property rights is without doubt the hereditary right that they have enjoyed since ancient times to oppress, to degrade, and to attach to their person legally and royally the 25 million people who lived, at their good pleasure, on the territory of France.

But to none of these people has it ever occurred that property carries moral responsibilities. Why should our Declaration of Rights appear to contain the same error in its definition of liberty: “the most valued property of man, the most sacred of the rights that he holds from nature”? We have justly said that this right was limited by the rights of others. Why have we not applied the same principle to property, which is a social institution, as if the eternal laws of nature were less inviolable than the conventions evolved by man? You have drafted numerous articles in order to ensure the greatest freedom for the exercise of property, but you have not said a single word to define its nature and its legitimacy, so that your declaration appears to have been made not for ordinary men, but for capitalists, profiteers, speculators and tyrants. I propose to you to rectify these errors by solemnly recording the following truths:

1. Property is the right of each and every citizen to enjoy and to dispose of the portion of goods that is guaranteed to him by law.

2. The right of property is limited, as are all other rights, by the obligation to respect the property of others.

3. It may not be so exercised as to prejudice the security, or the liberty, or the existence, or the property of our fellow men.

4. All holdings in property and all commercial dealings which violate this principle are unlawful and immoral.

You also speak of taxes in such a way as to establish the irrefutable principle that they can only be the expression of the will of the people or of its representatives. But you omit an article that is indispensable to the general interest: you neglect to establish the principle of a progressive tax. Now, in matters of public finance, is there a principle more solidly grounded in the nature of things and in eternal justice than that which imposes on citizens the obligations to contribute progressively to state expenditure according to their incomes—that is, according to the material advantages that they draw from the social system?

I propose that you should record this principle in an article conceived as follows:

“Citizens whose incomes do not exceed what is required for their subsistence are exempted from contributing to state expenditure; all others must support it progressively according to their wealth.”

The Committee has also completely neglected to record the obligations of brotherhood that bind together the men of all nations, and their right to mutual assistance. It appears to have been unaware of the roots of the perpetual alliance that unite the peoples against tyranny. It would seem that your declaration has been drafted for a human herd planted in an isolated corner of the globe and not for the vast family of nations to which nature has given the earth for its use and habitation.

I propose that you fill this great gap by adding the following articles. They cannot fail to win the regard of all peoples, though they may, it is true, have the disadvantage of estranging you irrevocably from kings. I confess that this disadvantage does not frighten me, nor will it frighten all others who have no desire to be reconciled to them. Here are my four articles:

1. The men of all countries are brothers, and the different peoples must help one another according to their ability, as though they were citizens of a single state.

2. Whoever oppresses a single nation declares himself the enemy of all.

3. Whoever makes war on a people to arrest the progress of liberty and to destroy the rights of man must be prosecuted by all, not as ordinary enemies, but as rebels, brigands and assassins.

4. Kings, aristocrats and tyrants, whoever they be, are slaves in rebellion against the sovereign of the earth, which is the human race, and against the legislator of the universe, which is nature.

A Proposed Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

The representatives of the French people, assembled in National Convention, recognizing that human laws which do not derive from the eternal laws of justice and of reason are only the outrages of ignorance or despotism against humanity; convinced that forgetfulness and contempt of the natural rights of man are the sole causes of the crimes and misfortunes of the world, have resolved to set forth in a solemn declaration these sacred and inalienable rights, in order that all citizens, being able constantly to compare the acts of the government with the aim of every social institution, may never allow themselves to be oppressed and degraded by tyranny, in order that the people always may have before their eyes the bases of their liberty and welfare; the magistrate, the rule of his duties; the legislator, the object of his mission.

Accordingly, the National Convention proclaims in the presence of the Universe, and before the eyes of the Immortal Legislator, the following declaration of the rights of man and citizen.

1. The aim of every political association is the maintenance of the natural and inalienable rights of man and the development of all their attributes.

2. The principal rights of man are those of providing for the preservation of his existence and his liberty.

3. These rights appertain equally to all men, whatever the difference in their physical and moral powers.

4. Equality of rights is established by nature; society, far from impairing it, guarantees it against the abuse of power which renders it illusory.

5. Liberty is the power which appertains to man to exercise all his faculties at will; it has justice for rule, the rights of others for limits, nature for principle, and the law for a safeguard.

6. The right to assemble peaceably, the right to manifest one’s opinions, either by means of the press or in any other manner, are such necessary consequences of the principle of the liberty of man that the necessity of enunciating them presumes either the presence or the recent memory of despotism.

7. The law may forbid only whatever is injurious to society; it may order only whatever is useful thereto.

8. Every law which violates the inalienable rights of man is essentially unjust and tyrannical; it is not a law at all.

9. Property is the right of each and every citizen to enjoy and to dispose of the portion of goods that is guaranteed to him by law.

10. The right of property is limited, as are all other rights, by the obligation to respect the rights of others.

11. It may not be so exercised as to prejudice the security, or the liberty, or the existence, or the property of our fellow men.

12. All holdings in property and all commercial dealings which violate this principle are unlawful and immoral.

13. Society is obliged to provide for the subsistence of all its members, either by procuring work for them or by assuring the means of existence to those who are unable to work.

14. The aid indispensable to whosoever lacks necessities is a debt of whosoever possesses a surplus; it appertains to the law to determine the manner in which such debt is to be discharged.

15. Citizens whose incomes do not exceed whatever is necessary for their subsistence are exempted from contributing to public expenditures; all others must support them progressively, according to the extent of their wealth.

16. Society must favor with all its power the progress of public reason and must place education within reach of all citizens.

17. The law is the free and solemn expression of the will of the people.

18. The people is the sovereign, the government is its work, the public functionaries are its clerks; the people may change its government and recall its representatives when it pleases.

19. No portion of the people may employ the power of the entire people; but the wish which it expresses must be respected as the wish of a portion of the people, which is to concur in forming the general will. Each and every section of the assembled sovereign must enjoy the right to express its will with entire liberty; it is essentially independent of all constituted authorities and master of regulating its police and its deliberations.

20. The law must be equal for all.

21. All citizens are admissible to all public offices, without any distinction other than that of virtues and talents, without any title other than the confidence of the people.

22. All citizens have an equal right to concur in the nomination of the representatives of the people and in the formation of the law.

23. In order that these rights may not be illusory, and equality chimerical, society must pay the public functionaries and must arrange that citizens who live by their labor may be present at the public assemblies to which the law summons them without compromising their existence or that of their family.

24. Every citizen must obey religiously the magistrates and agents o£ the government when they are the spokesmen or the executors of the law.

25. But every act against the liberty, the security, or the property of a man, performed by anyone whomsoever, even in the name of the law, except in the cases determined and the forms prescribed thereby, is arbitrary and null; every respect for the law forbids submission thereto; and if it is executed by violence, it is permissible to repel it by force.

26. The right to present petitions to the depositaries of public authority appertains to every individual. Those to whom they are addressed ought to legislate on the matters which are the object thereof; but they may never forbid, restrain, or condemn the exercise of said right.

27. Resistance to oppression is the consequence of the other rights of man and citizen.

28. There is oppression against the social body when a single one of its members is oppressed. There is oppression against each and every member of the social body when the social body is oppressed.

29. When the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is the most sacred of rights and the most indispensable of duties for the people and for each and every portion thereof.

30. When the social guarantee is lacking to a citizen, he returns to the natural right of defending all his rights himself.

31. In either case, to make resistance to oppression subject to legal forms is the last refinement of tyranny. In every free state the law must, above all, defend public and individual liberty against the abuse of the authority of those who govern: every institution which does not assume that the people are good, and the magistrate corruptible, is vicious.

32. Public functions may not be considered as distinctions or rewards, but only as public duties.

33. Offenses of the mandataries of the people must be punished severely and promptly. No one has a right to claim himself more inviolable than other citizens. The people have a right to know what their mandataries are doing; these must render a faithful account of their activities and must submit to public judgment respectfully.

34. The men of all countries are brothers, and the different peoples must help one another, according to their power, as citizens of the same State.

35. Whoever oppresses a single nation declares himself the enemy of all.

36. Whoever make war on a people in order to check the progress of liberty and annihilate the rights of man must be prosecuted by all, not as ordinary enemies, but as rebels, brigands and assassins.

37. Kings, aristocrats, tyrants, whoever they be, are slaves rebelling against the sovereign of the earth, which is the human race, and against the legislator of the universe, which is nature.

Afficher davantage

139 notes

·

View notes

Note

Apologies if this is a somewhat irritating or strange question,but you think the claims of Robespierre opposing the abolition of slavery hold any weight? I've been attempting to research this myself and I often encounter information that seems contradictory in regards to both possibilities.

There are people who researched this in more detail and provided receipts. I believe @lanterne wrote about it?

Robespierre was pro abolition of slavery. As early as 1791, when many were "but oh no, if we abolish slavery, our economy will suffer! The colonies will be ruined!", Robespierre was like "then let them be ruined. Slavery is wrong and should not exist."

It is true though that the French government took its sweet time getting to the abolition of the slavery. It happened in february 1794, and only after the people of Haiti (Saint-Domingue) liberated themselves (or was at least clear that the slave uprising was successful). So they could have done it sooner, especially since the Convention was, nominally at least, all against slavery and pro abolition.

As I understand, the whole "Robespierre was against the abolition of the slavery" was due to an agent from Saint-Domingue (himself black or mixed) claiming that the abolition should not happen at that moment? So deputies (including Robespierre) took his word and acted on it, except that was a plant by the anti-abolition crowd and they later realized? I am not sure. Like I said, I am not an expert on what happened, but I know there was a stalling due to some misinformation.

If anyone knows more, please share! There were numerous posts about this exact thing with receipts but I can't remember what was said exactly and I can't find any of them.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Hymn from the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes

This was sung in honor of the club's inauguration of busts depicting Mirabeau, Franklin, Rousseau and Voltaire.

On this day of allegiance and gratitude,

may Franklin and Mirabeau be carried to

heaven;

Scourges of despotism and supporters of France,

Free people, they are your gods.

Let us celebrate the memory of the sublime Rousseau;

Virtue had chosen his heart as a sanctuary:

Constant friend of man, he applied all his

glory

To make him free and better.

Let us no longer water Voltaire's ashes with tears,

It's a day for pleasure, not regret;

He returns full of glory to announce to the earth,

That a great man never dies.

Now illuminated by the fire of their brilliance,

Dare to tell tyrants the truth, like them;

Models of great hearts, live for the fatherland,

But die for liberty!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

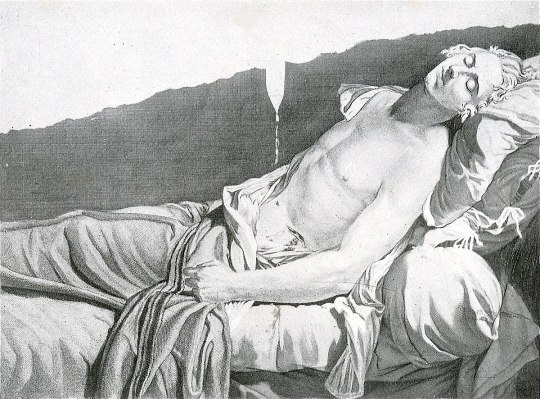

Martyr and friend of the people, sketch cross-referenced from various paintings (thanks, David...)

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I'm having a crappy day at work, I sometimes visit "L'Ami du Peuple" during my lunch break. It tends to put all the petty day-to-day stuff into perspective…

During the quieter moments, like today, when room 55 is nearly empty, I can't help but notice a pattern. Every single visitor, upon entering, pauses before the painting.

They do a double-take at the painting's name and give him another look. Some snap a photo they'll probably never look at again.

Then they move on.

Most of them likely have no clue who he is. They don't know he's holding a note from his assassin. If they even notice "L'An Deux" written at the bottom, they're probably confused by it.

But still, for those 30 seconds, David's brushstrokes that bring to life the exquisite face of this stricken man make them pause. What makes them linger? Is it the vaguely familiar name? The face they've seen on numerous posters and leaflets? The unsettling quiet brutality of the piece?

It doesn’t really matter why. Because, for that half-minute, through their eyes, he exists. He is present. He is contemporary.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

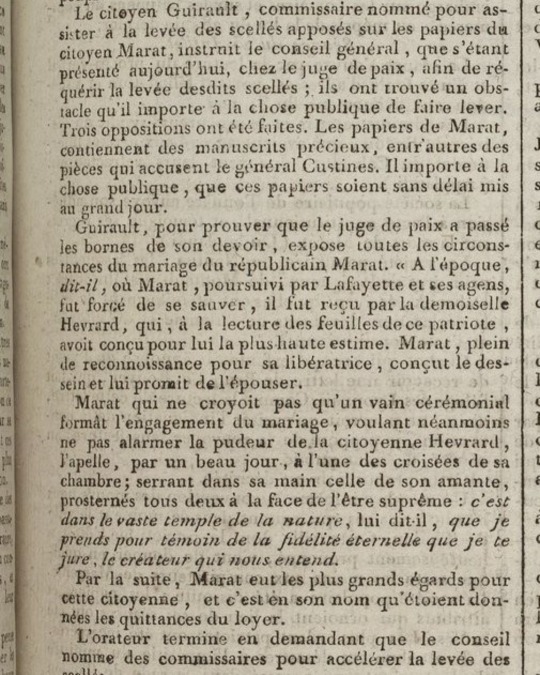

Here is the document where the testimony of the citoyen Guirault about the marriage of Marat and Simonne is reported, in issue 53 of the Journal de La Montagne. The text's reliability has obviously been questioned, but I don't particularly believe that it can be absolutely false, given the fact that Guirault (who, by the way, was the author of Marat's Oraison funèbre) was referring to a kind of ceremony full of Rousseanism, which seems to me to be Marat's style. This interesting post allows us to reflect a little on the subject and also on the nature of the republican/revolutionary/unofficial marriages that seemed popular at the time.

marat and simonne évrards relationship is so bizarre to me. me and my sugar daddy who is a woman 20 years younger than me. if we are married. we arent married because we are. no we arent <3

#i know op was joking!#it's really frustrating how little we know about them as a couple#it's even more frustrating how little information we have about simonne#who despite obviously being one of the most important people to marat and who supported him and his ideas unconditionally in every way#is often forgotten and barely mentioned even in the most complete biographies about marat#simonne évrard#marat#my posts

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Workers, do not be deceived: it is the great struggle: parasitism and labor, exploitation and production are at death-grips. If you are sick or vegetating in ignorance and squatting in the muck; if you want your children to be men gaining the reward of their labor, not a sort of animal trained for the workshop and for war, fertilizing with its sweat the fortune of an exploiter, or pouring out its blood for a despot; if you want the daughters whom you cannot bring up and watch over as you would, to be no longer instruments of pleasure in the arms of the aristocracy of wealth; if you want debauch and poverty no longer to drive men to the police and women to prostitution; if, finally, you desire the reign of justice, workers, be intelligent, arise! And let your stout hands fling beneath your feet the foul reaction! ...Long live the Republic! Long live the Commune!"

--Statement of the Central Committee of the National Guard of the Paris commune on April 5, 1871.

The National Guard of the Commune was not the same as the old government's army that defended bourgeois interest; the National Guard of the Commune consisted of the workingmen of Paris. Their officers and Central Committee were democratically elected and subject to recall if they lost the confidence of the people.

The Paris Commune started today, March 18, in 1871. At the time the working people of Paris were driven to poverty and starvation by the war with Prussia. On this day in 1871 the people of Paris--especially women and children--chased out the bourgeois government, who ran away pitifully with their tails between their legs to Versailles, leaving the city to the control of its workers. The workers of Paris established their own government that sought not to merely address urgent and base concerns such as hunger, rent, and unemployment, but also to found a kinder society by radicalizing institutions such as education or the concept of the family. It was the first attempt at a workers' state in history.

The Commune lasted for only 72 days, when the French government violently and ruthlessly crushed it. They brutally massacred the workers in the event that is known as Bloody Week. Historian Donny Gluckstein wrote: "Bloody Week was a graphic example of a capitalist state stripped to its bare essentials--'armed bodies of men'--exterminating a threat to the system of domination and exploitation." Paris suffered a labor shortage after this massacre.

We remember the Paris Commune, its principles, and its battle. Even today we sing the Internationale, a product of that relentless hopeful spirit of the Commune and its people who dared to believe a kinder world was possible--if only we fight for it.

Picture is the Communards Wall at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, where workers of the Commune were killed by bourgeois forces. People still leave flowers every year.

645 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand the story of marat and his assassination event

But who is lepeletier?

Because I saw a drawing for him by louis David and I learned about his death which happen to be the same as Marat so yeah .. I wanna know about him.

According to the biography Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), its subject of study was born on 29 May 1760, in his family home on rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine, a building which today is the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His family belonged to the distinguished part of the robe nobility. At the death of his father in 1769, Lepeletier was both Count of Saint-Fargeau, Marquis of Montjeu, Baron of Peneuze, Grand Bailiff of Gien as well as the owner of 400,000 livres de rente. For five years he worked as avocat du roi at Châtelet, before becoming councilor in Parliament in 1783, general counsel in 1784 and finally taking over the prestigious position of président à mortier at the Parlement of Paris from his father in 1785. On May 16 1789, Lepeletier was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General. On June 25 the same year he was one of the 47 nobles to join the newly declared National Assembly, two days before the king called on the rest of the first two estates to do so as well. A month later, during the night of August 4 1789, he was in the forefront of those who proposed the suppression of feudalism, even if, for his part, this meant losing 80 000 livres de rente. Four days later he wrote a letter to the priest of Saint-Fargeau, renouncing his rights to both mills, furnaces, dovecote, exclusive hunting and fishing, insence and holy water, butchery and haulage (the last four things the Assembly hadn’t ruled on yet). When the Assembly on June 19 1790 abolished titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility, Lepeletier made the motion that all citizens could only bear their real family name — ”The tree of aristocracy still has a branch that you forgot to cut..., I want to talk about these usurper names, this right that the nobles have arrogated to themselves exclusively to call themselves by the name of the place where they were lords. I propose that every individual must bear his last name and consequently I sign my motion: Michel Lepeletier” — and the same year he also, in the name of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, presented a report on the supression of the penal code and argued for the abolition of the death penalty. After the closing of the National Assembly in 1791, Lepeletier settled in Auxerre to take on the functions of president of the directory of Yonne, a position to which he had been nominated the previous year. He did however soon thereafter return to Paris, as he, following the overthrow of the monarchy, was one of few former nobles elected to the National Convention, where he was also one of even fewer former nobles to sit together with the Mountain. In December 1792 he started working on a public education plan. On January 20 1793, he voted for death without a reprieve and against an appeal to the people during the trial of Louis XVI (Opinion de L.M. Lepeletier, sur le jugement de Louis XVI, ci-devant roi des François: imprimée par ordre de la Convention nationale). After the session was over, Lepeletier went over to Palais-Égalité (former Palais-Royal) where he dined everyday. The next day, his friend and fellow deputy Nicolas Maure could report the following to the Convention:

Citizens, it is with the deepest affection and resentment of my heart that I announce to you the assassination of a representative of the people, of my dear colleague and friend Lepelletier, deputy of Yonne; committed by an infamous royalist, yesterday, at five o'clock, at the restaurateur Fevrier, in the Jardin de l'Égalité. This good citizen was accustomed to dining there (and often, after our work, we enjoyed a gentle and friendly conversation there) by a very unfortunate fate, I did not find myself there; for perhaps I could have saved his life, or shared his fate. Barely had he started his dinner when six individuals, coming out of a neighboring room, presented themselves to him. One of them, said to be Pâris, a former bodyguard, said to the others: There's that rascal Lepeletier. He answered him, with his usual gentleness: I am Lepeletier, but I am not a rascal. Paris replied: Scoundrel, did you not vote for the death of the king? Lepelletier replied: That is true, because my confidence commanded me to do so.Instantly, the assassin pulled a saber, called a lighter, from under his coat and plunged it furiously into his left side, his lower abdomen; it created a wound four inches deep and four fingers wide. The assassin escaped with the help of his accomplices. Lepeletier still had the gentleness to forgive him, to pray that no further action would be taken; his strength allowed him to make his declaration to the public officer, and to sign it. He was placed in the hands of the surgeons who took him to his brother, at Place Vendôme. I went there immediately, led by my tender friendship, and my reverence for the virtues which he practiced without ostentation: I found him on his death bed, unconscious. When he showed me his wound, he uttered only these two words: I'm cold. He died this morning, at half past one, saying that he was happy to shed his blood for the homeland; that he hoped that the sacrifice of his life would consolidate Liberty; that he died satisfied with having fulfilled his oaths.

This was the first time a Convention deputy had gotten murdered, and it naturally caused strong reactions. Already the same session when Maure had announced Lepeletier’s death, the Convention ordered the following:

There are grounds for indictment against Pâris, former king's guard, accused of the assassination of the person of Michel Lepelletier, one of the representatives of the French people, committed yesterday.

[The Convention] instructs the Provisional Executive Council to prosecute and punish the culprit and his accomplices by the most prompt measures, and to without delay hand over to its committee of decrees the copies of the minutes from the justice of the peace and the other acts containing information relating to this attack.

The Decrees and Legislation Committees will present, in tomorrow's session, the drafting of the indictment.

An address will be written to the French people, which will be sent to the 84 departments and the armies, by extraordinary couriers, to inform them of the crime against the Nation which has just been committed against the person of Michel Lepelletier, of the measures that the National Convention has taken for the punishment for this attack, to invite the citizens to peace and tranquility, and the constituted authorities to the most exact surveillance.

The entire National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepelletier, assassinated for having voted for the death of the tyrant.

The honors of the French Pantheon are awarded to Michel Lepelletier, and his body will be placed there.

The president is responsible for writing, on behalf of the National Convention, to the department of Yonne, and to the family of Lepelletier.

The next day, January 22, further instructions were given regarding Lepeletier’s funeral:

On Thursday January 24, Year 2 of the Republic, at eight o'clock in the morning, will be celebrated, at the expense of the Nation, the funeral of Michel Lepeletier, deputy of the department of Yonne to the National Convention.

The National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepeletier in its entirety. The executive council, the administrative and judicial bodies will attend it as well.

The executive council and the department of Paris will consult with the Committee of Public Instruction regarding the details of the funeral ceremony.

The last words spoken by Michel Lepeletier will be engraved on his tomb, they are as follows: “I am happy to shed my blood for the homeland; I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality; and to make their enemies recognized.”

In number 27 (January 27 1793) of Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, the following long description was given over Lepeletier’s funeral, held three days earlier:

The funeral of Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau was celebrated on Thursday 24 with all the splendor that the severity of the weather and the season allowed, but with such a crowd that it could have been the most beautiful day of the year. At ten o'clock in the morning his deathbed was placed on the pedestal where the equestrian statue of Louis XVI previously stood, on Place Vendôme, today Place des Piques. One went up to the pedestal by two staircases, on the banisters of which were antique candelabras. The body was lying on the bed with the bloody sheets and the sword with which he had been struck. He was naked to the waist, and his large and deep wound could be seen exposed. These were the mournful and most endearing part of this great spectacle. All that was missing was the author of the crime, chained, and beginning his torture by witnessing the sight of the triumph of Saint-Fargeau.

As soon as the National Convention and all the bodies that were to form courage were assembled in the square, mournful music was played. It was, like almost all those which has embellished our revolutionary festivals, the composition of citizen Gossec. The Convention was ranged around the pedestal. The citizen in charge of the ceremonies presented the President of the Convention with a wreath of oak and flowers; then the president, preceded by the ushers of the Convention and the national music, went around the monument, and went up to the pedestal to place the civic crown on Lepeletier's head: during this time, a federate gave a speech; the president dismounted, the procession set out in the following order: A detachment of cavalry preceded by trumpets with fourdincs. Sappers. Cannoneers without cannons. Detachment of veiled drummers. Declaration of the rights of man carried by citizens. Volunteers of the six legions, and 24 flags. Drum detachment. A banner on which was written the decree of the Convention which ordered the transport of Lepeletier's body to the Pantheon. Students of the homeland. Police commissioners. The conciliation office. Justices of the peace. Section presidents and commissioners. The commercial court. The provisional criminal court. The department’s fix courts. The electorate. The provisional criminal court. The department's criminal courts fix. The municipality of Paris. The districts of Saint-Denis and the village of L’Égalité. The Department. Drum detachment. The seal of the 84, worn by Federates. The provisional executive council. National Convention Guard Detachment. The court of cassation. Figure of Liberty carried by citizens. The bloody clothes worn at the end of a national pike, deputies marching in two columns. In the middle of the deputies was a banner where Lepeletier's last words were written: "I am happy to shed my blood for my homeland, I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality, and to make their enemies known.”

The body carried by citizens, as it was exhibited on the Place des Piques. Around the body, gunners, sabers in hand, accompanied by an equal number of Veterans. Music from the National Guard, who performed funeral tunes during the march. Family of the dead. Group of mothers with children. Detachment of the Convention Guard. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Armed federations. Popular societies. Cavalry and trumpets with fourdines. On each side, citizens, armed with pikes, formed a barrier and supported the columns. These citizens held their pikes horizontally, at hip height, from hand to hand. The procession left in this order from the Place des Piques, and passed through the streets St-Honoré, du Roule, the Pont-Neuf, the streets Thionville (former Dauphine), Fossés Saint-Germain, Liberté (former Fossés M. le Prince), Place Saint-Michel and Rue d'Enfer, Saint-Thomas, Saint-Jacques and Place du Panthéon. It stopped front of the meeting room of the Friends of Liberty and Equality; opposite the Oratory, on the Pont-Neuf, opposite the Samaritaine; in front of the meeting room of the Friends of the Rights of Man; at the intersection of Rue de la Liberté; Place Saint-Michel and the Pantheon. Arriving at the Pantheon, the body was placed on the platform prepared for it. The National Convention lined up around it; the band, placed in the rostrum, performed a superb religious choir; Lepeletier's brother then gave a speech, in which he announced that his brother had left a work, almost completed, on national education, which will soon be made public; he ended with these words: I vote, like my brother, for the death of tyrants. The representatives of the people, brought closer to the body, promised each other union, and swore on the salvation of the homeland. A big chorus to Liberty ended the ceremony.

According to Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), civic festivals in honor of Lepeletier were celebrated in all sections of Paris, as well as the towns of Arras, Toulouse, Chaumont, Valenciennes, Dijon, Abbeville and Huningue. Lepeletier’s body did however only get to rest in the Panthéon for a little more than a year, as on February 15 1795, the Convention ordered it exhumed, at the same time as that of Marat. It was instead buried in the park surrounding Château de Ménilmontant, the properly of which the ancestor Lepeletier de Souzy had purchased in the 17th century and that still remained in the family.

One day after the funeral, January 25, Lepeletier’s only child, the ten and a half year old Susanne, who had already lost her mother ten years before the murder of her father, was brought before the Convention by her step-mother and two paternal uncles Amédée and Félix. It was Félix who had held a speech during the funeral and he would continue to work for his seven years older brother’s memory afterwards too, offering a bust of him to the Convention on February 21 1793, (on the proposal of David, it was placed next to the one of Brutus), reading his posthumous work on public education to the Jacobins on July 19 1793, and even writing a whole biography over his life in 1794 (Vie de Michel Lepeletier, représentant du peuple français, assassiné à Paris le 20 janvier 1793 : faite et présentée a la Société des Jacobins).

The president announces that the widow of Michel Lepelletier, his two brothers and his daughter, request to be admitted to the bar, to testify to the Convention their recognition of the honors that they have decreed in memory of their relative. It is decreed that they will be admitted immediately.

One of Michel Lepeletier’s brothers: Citizens, allow me to introduce my niece, the daughter of Michel Lepelletier; she comes to offer you and the French people her recognition of the eternity of glory to which you have dedicated her father... He takes the young citoyenne Lepelletier in his arms, and makes her look at the president of the Convention... My niece, this is now your father... Then, addressing the members of the Convention, and the citizens present at the session: People, here is your child... Lepelletier pronounces these last words in an altered voice: silence reigns throughout the room, with exception for a couple of sobs.

The President: Citizens, the martyr of Liberty has received the just tribute of tears owed to him by the National Convention, and the just honor that his cold skin has received invites us to imitate his example and to avenge his death. But the name of Lepelletier, immortal from now on, will be dear to the French Nation. The National Convention, which needs to be consoled, finds relief to its pain in expressing to his family the just regrets of its members and the recognition of the great Nation of which it is the organ. The Nation will undoubtedly ratify the adoption of Michel Lepelletier's daughter that is currently being carried out by the National Convention.

Barère: The emotion that the sight of Michel Lepeletier's only daughter has just communicated to your souls must not be infertile for the homeland. Susanne Lepelletier lost her father; she must find now find one in the French people. Its representatives must consecrate this moment of all-too-just felicity to a law that can bring happiness to several citizens and hope to several families. The errors of nature, the illusions of paternity, the stability of morals, have long demanded this beautiful institution of the Romans. What more touching time could present itself at the National Convention to pass into French legislation the principle of adoption, than that when the last crimes of expiring tyranny deprived the homeland of one of its ardent defenders and Susanne Lepelletier of a dear father! Let the National Convention therefore give today the first example of adoption by decreeing it for the only offspring of Lepelletier; let it instruct the Legislation Committee to immediately present the bill on this interesting subject. I ask that the homeland adopt through your organ Susanne Lepelletier, daughter of Michel Lepelletier, who died for his country; that it decrees that adoption will be part of French legislation, and instructs its Legislation Committee to immediately present the draft decree on adoption.

This proposal is unanimously approved.

Susanne being adopted by the state would however lead to a fierce debate when, in 1797, this ”daughter of the nation” wished to marry a foreigner. For this affair, see the article Adopted Daughter of the French People: Suzanne Lepeletier and Her Father, the National Assembly (1999)

Right after Barère’s intervention, David took to the rostrum:

David: Still filled with the pain that we felt, while attending the funeral procession with which we honored the inanimate remains of our colleagues, I ask that a marble monument be made, which transmits to posterity the figure of Lepelletier , as you clearly saw, when it was brought to the Pantheon. I ask that this work be put into competition.

Saint-André: I ask that this figure be placed on the pedestal which is in the middle of Place Vendôme... (A few murmurs arise)

Jullien: I ask that the Convention adopt in advance, in the name of the homeland, the children of the defenders of Liberty, who, for similar reasons, could be immolated in the vengeance of the royalists.

All these proposals are referred to the Legislation and Public Instruction Committees.

On Maure's proposal, the Assembly orders the printing of the speeches delivered yesterday at the Panthéon, by one of Michel Lepelletier's brothers, Barère and Vergniaux.

If it would appear David never got to make a marble monument of Lepeletier, on March 28 1793, he could nevertheless present the following painting of his to the Convention, which isn’t just a little similar to his La Mort de Marat.

(This image is an engraving of the actual painting, which has gone missing)

After Marat on July 13 1793 (on the very same day the plan for public education Lepeletier had been working on was read to the Convention by Robespierre) became the second assassinated Convention deputy, we find several engravings etc, depicting the two ”martyrs of liberty” side by side.

In the following months, even more people would be join the two, such as Joseph Chalier, a lyonnais politician executed on July 17 1794 and Joseph Bara, a fourteen year old republican drummer boy killed in the Vendée by the pro-Monarchist forces.

Lepeletier’s murderer, 27 year old Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, a man who the minister of justice described as "former king's guard, height five pieds, five pouces, barbe bleue, and black hair; swarthy complexion, fine teeth, dressed in a gray cloak, green lapels and a round hat” on January 21, went into hiding right after his deed. In spite of his description being published in the papers and a considerable sum of money being promised to whoever caught him, Pâris managed to flee Paris and settled for a country house of an acquaintance near Bourget. He there ran into a cousin of one of the owners. When Pâris asked for food and a bed, he was refused and instead disappeared into the night again. In the evening of January 28 he arrived in Forges-les-Eaux and stopped at an inn, where he came under suspicion once he started cutting his bread with a dagger after which he locked himself into his room. The following morning he woke up with a start as five municipal gendarmes came bursting into his room and told him to come with them. Pâris responded that he would, but in the next second he had picked up his hidden pistol, placed it into his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Searching the dead body, the gendarmes found Pâris’ baptism record (dated November 12 1765) and dismissal from the king's guard (dated June 1 1792), on the latter of which had been written the following:

My certificate of honor. Do not trouble anyone. No one was my accomplice in the fortunate death of the scoundrel de Saint-Fargeau. Had I not run into him, I would have carried out a more beautiful action: I would have purged France of the patricide, regicide and parricide d’Orléans. The French are cowards to whom I say:

Peuple dont les forfaits jettent partout l'effroi, Avec calme et plaisir j'abandonne la vie.

Ce n'est que par la mort qu'on peut fuir l'infamie Qu'imprime sur nos fronts le sang de notre roi.

Signed by Paris the older, guard of the king, assassinated by the French.

Learning about what had happened, the Convention tasked Tallien and Legrand with going to Forges-les-Eaux and making sure the dead man really was Pânis. Having come to the conclusion that this was indeed the case, the deputies briefly discussed whether the body ought to be brought back to Paris, but it was decided it would be better if it was just buried "with ignominy.” It was therefore instead taken into the nearby forest in a wheelbarrow and thrown into a six feet deep hole.

Finally, here are some other revolutionaries simping for honoring Lepeletier’s memory just because I can:

…a tragic event took place the day before the execution [of the king]. Pelletier, one of the most patriotic deputies, and who had voted for death, was assassinated. A king's guard made a wound three fingers wide with a saber: he died this morning. You must judge the effect that such a crime has had on the friends of liberty. Pelletier had an income of six hundred thousand livres; he had been président à mortier in the Parliament of Paris; he was barely thirty years old; to many talents, he added the most estimable of virtues. He died happy, he took to his grave the idea, consoling for a patriot, that his death would serve the public good. Here then is one of these beings whom the infamous cabal who, in the Convention, wanted to save Louis and bring back slavery, designated to the departments as a Maratist, a factious, a disorganizer... But the reign of these political rascals is finished. You will see the measures that the Assembly took both to avenge the national majesty and to pay homage to a generous martyr of liberty.

Philippe Lebas in a letter to his father, January 21 1793

Ah! if it is true that man does not die entirely and that the noblest part of himself survives beyond the grave and is still interested in the things of life, come then, dear and sacred shadow, sometimes to hover above the Senate of the nation that you adorned with your virtues; come and contemplate your work, come and see your united brothers contributing to the happiness of the homeland, to the happiness of humanity.

Marat in number 105 (January 23 1793) of Journal de la République Française

O Lepeletier! Your death will serve the Republic: I envy your death. You ask for the honors of the Pantheon for him, but he has already collected the prize of martyrdom of Liberty. The way to honor his memory is to swear that we will not leave each other without having given a constitution to the Republic.

Danton at the Convention, January 21 1793

O Le Peletier, tu étais digne de mourir pour la patrie sous les coups de ses assassins ! Ombre chère et sacrée, reçois nos vœux et nos serments ! Généreux citoyen, incorruptible ami de la vérité, nous jurons par tes vertus, nous jurons par ton trépas funeste et glorieux de défendre contre toi la sainte cause dont tu fus l'apôtre; nous jurons une guerre éternelle au crime dont tu fus l'éternel ennemi, à la tyrannie et à la trahison, dont tu fut la victime. Nous envions ta mort et nous saurons imiter ta vie. Elles resteront à jamais gravées dans nos cœurs, ces dernières paroles où lu nous montrais ton âme tout entière; ”Que ma mort, disais tu, sera utile à la patrie, qu'elle serve à faire connaître les vrais et les faux amis de la liberté, et je meurs content.

Robespierre at the Jacobins, January 23

Wednesday 23 [sic] — We went to Madame Boyer’s to see the procession. I saw the poor Saint-Fargeau. We all burst into tears when the body passed by, we threw a wreath on it. After the ceremony, we returned to my house. Ricord and Forestier had arrived. I was unable to stop my tears for some time. F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite fun and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire and, our imaginations struck by what we had seen, we talked about it for a while. She wanted to leave, I felt that I could not be alone and bear the horrible thoughts that were going to besiege me. I ran to D(anton’s). He was moved to see me still pale and defeated. We drank tea, I supped there.

Lucile Desmoulins in her diary, January 24 1793

…Pelletier's funeral took place this Thursday as I informed you in my last letter (this letter has gone missing). The procession was immense; it seemed that the population of Paris had doubled, to honor the memory of this virtuous citizen. The mourning of the soul was painted on all the faces: it was especially noticed that the people were extremely affected, which proves that they keenly felt the price of the friend they had lost. Arriving at the Pantheon, Lepelletier's body was placed on the platform prepared for it; his brother delivered a speech which was applauded with tears; Barère succeeded him. Then the members of the Convention, crowding around the body of their colleague, promised union among themselves, and took an oath to save the country. God grant that we have not sworn in vain, that we finally know the full extent of our duties, and that we only occupy ourselves with fulfilling them! In yesterday's session, Pelletier's daughter, aged eight [sic], was presented to the National Convention, which immediately adopted her as a child of the homeland.

Georges Couthon in a letter written January 26 1793

How could I be so base as to abandon myself to criminal connections, I who, in the world, have never had more than one close friend since the age of six? (he gestures towards David's painting). Here he is! Michel Lepeletier, oh you from whom I have never parted, you whose virtue was my model, you who like me was the target of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr! I envy your glory. I, like you, will rush for my country in the face of liberticidal daggers; but did I have to be assassinated by the dagger of a republican!

Hérault de Sechelles at the Convention, December 29 1793

For a collection of Lepeletier’s works, see Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau, député aux assemblées constituante et conventionnelle, assassiné le 20 janvier 1793, par Paris, garde du roi (1826)

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recommend, especially to those who have doubts or difficulties understanding Marat's social-political thinking with regard to his continuous demands for the establishment of a "dictatorship" or "triumvirate", to read this excellent article written by Cesare Vetter, professor of history at the University of Trieste, and published in 2009 on the revolution-francaise.net website. It's a study full of very interesting analyses strictly linked to the lexicometric and semantic details used in the writings of L'Ami du Peuple.

The article is only available in French, but I would like to translate it, if possible, in the near future, as it is very worthwhile reading. The research covers various themes addressed by Marat relating to the dictatorship for which he so unapologetically clamored. In "section" 7 of the article, which refers to "Dictatorship and revolutionary committees", it is possible to understand much more clearly Marat's opinion on the committee of public safety and what he believed should be changed in its structure based on his own political principles. I'm very keen to translate this part in particular, considering that, in a previous post, an anon asked a question on the subject and I believe that some excerpts from this article can complement my answer.

I didn't know Professor Vetter and this was the first thing of his I've read, but it seems he's written a few other works on the Revolution that involve this kind of semantic observation, which I find very interesting. Reading this article clarified several things for me, as well as providing a different and curious point of view regarding Marat's idea of dictatorship, which was undoubtedly presented as very innovative.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marat's Address to the Parisians

Le Junius Français, no .1, June 2 , 1790.

O Parisiens ! hommes légers, faibles & pusillanimes, dont le goût pour les nouveautés va jusqu’à la fureur, & dont la passion pour les grandes choses n’est qu’un accès passager ; qui raffolez de la liberté comme des modes du jour ; qui n’avez ni lumières, ni plan, ni principes ; qui préférez l’adroit flagorneur au conseiller sévère ; qui méconnaissez vos défenseurs ; qui vous abandonnez à la foi du premier venu ; qui vous livrez à vos ennemis sur leur parole ; qui pardonnez aux perfides et aux traîtres, au premier signe contrition ; qui dans vos projets ou vos vengeances, suivez sans cesse l’impulsion du moment ; qui êtes toujours prêts à donner un coup de collier ; qui allez au bien par vanité, et que la nature eût donné de la judiciaire et de la constance : faudra-t-il donc toujours vous traiter comme de vieux enfants ?

Les leçons de la sagesse, et les vues de la prudence ne sont plus faites pour vous. Des légions de folliculaires faméliques vous ont blasés à force de sottises et d’atrocités ; les bonnes choses glissent sur vous sans effet : déjà vous ne prenez plaisir qu’aux conseils outrés, aux traits déchirants, aux invectives grossières : déjà les termes les plus forts vous paraissent sans énergie : et bientôt vous n’ouvrirez l’oreille qu’aux cris d’alarme, de meurtre, de trahison. Tant de fois agités pour des riens, comment fixer votre attention ; comment vous tenir en garde contre toute surprise ; comment vous tenir continuellement éveillés ? Un seul moyen me reste, c’est de suivre vos goûts, et de varier mon ton. O Parisiens ! Quelque bizarre que ce rôle paraisse aux yeux du sage, votre ancien ami ne dédaignera pas de le prendre, il n’est occupé que du soin de votre salut ; pour vous empêcher de retomber dans l’abîme, il n’est point d’efforts qu’il ne fasse, et toujours le Junius Français sera votre incorruptible défenseur, votre défenseur intrépide.

my translation:

O Parisians! Lightweight, feeble, and pusillanimous men, your appetite for novelties reaches furious excess, and your passion for grand things is but a brief flicker; you craze after freedom as if crazing after fashions of the day; you have neither insight, nor plan, nor principles; you prefer the skilful sycophant to the stern advisor; you disregard your defenders; you let yourselves be swayed by whosoever comes along first; you hand yourselves over to your enemies over their word; you forgive the perfidious and the treacherous at the first sign of contrition; through your projects or your vengeance you are unceasingly following your impulse of the moment; you are always ready to give another push; you seek to do good out of vanity, and nature ought to have given you judiciousness and constancy: will you forever need to be treated like overgrown children?

The lessons of wisdom, and the views of prudence are no longer made for you. Legions of famished fillers of periodical papers have wearied you with silliness and with atrocities; the good things are sliding over you unnoticed: already you only feel pleased with the overblown advices, the agonising remarks, the gross invectives: already you find the strongest words to lack energy: and soon you will only open your ears to cries of alarm, of murder, of treason. So often agitated by nothing, how could your attention be fixed; how can you be put on guard against all surprises; how can you be kept continually awake? I have been left with only one way, and that is to conform to your appetites and to vary my tone. O Parisians! However bizarre this role might seem to the eyes of the wise, your old friend will not begrudge to perform it, he is occupied but with your very survival; to prevent you from relapsing into the abyss, no single effort will he not make, and always the Junius Français will be your incorruptible defender, your defender undaunted.

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

(i know you're probably very busy so feel free to ignore this)

maybe some random frev modern au shenanigans?

I present you more modern saintspierre brainrot:

Also for the other anon who had an idea suggestion for charlotte running into Marat, sorry that I didn't draw exactly that but i hope you enjoy modern au Charlotte:

117 notes

·

View notes

Note

more on jamgate?

i read charlotte’s memoirs years ago but i dont remember the details

Sorry for my late reply! I love to call it "The Great Jamgate of 1793", but in truth I am unsure when it happened. Does anyone know when Charlotte persuaded Robespierre to come live with her, but then he got sick and Mme Duplay brought him back to Duplays? The jamgate happens after that. (So it could be the Great Jamgate of 1791 or 1792, lol).

Charlotte tells us how she loved making jams for her brother, who had a taste for sweets and fruits. She would send her maid to Duplays to deliver jams, and, according to Charlotte, Mme Duplay always had a snarky comment on that.

The worst happend one time when Mme Duplay sent the maid back, refusing to accept jams, saying something along the lines of "Bring that back, I don't want her to poison Robespierre".

Naturally and understandably, Charlotte was shocked and hurt. It was inded a shitty thing to say, even as a "joke". In line with the narrative Charlotte built about herself in the memoirs, she claims that she "swallowed her sadness" and said nothing to Mme Duplay or Maximilien (as to not cause him pain).

Of course, we have to remember that this is Charlotte's version of the story (we don't have one from Duplays), and Charlotte is not always the most reliable of the narrators. Still, the anecdote seems too specific to just be made up, so I am willing to believe that there was indeed a Great Jamgate of some sorts. We do know that Mme Duplay didn't like Charlotte much, and it's possible that she ridiculed her cooking skills. (Those two women seemed to fight over who would pamper Maximilien). Mme Duplay obviously saw herself as superior, and tbh, she probably was, but I doubt that she really thought that Charlotte wanted to bring harm to her brother (?)

Still, I can see Mme Duplay saying something snarky about Charlotte's cooking. But I can't guess anything more than that.

The way Charlotte described the Jemgate, it has all the typical story points of her narrative: there is always a harpy woman who hates her and tries to take her away from her brothers. The harpy is horrible, but she (Charlotte) never says anything because she is good and non-confrontational, and she doesn't want to hurt her brothers or cause any problems.

Needless to say, this goes against everything that we know of her character from other sources. Charlotte comes off as too outspoken and stubborn for this meek and obedient image she paints of herself, not to mention that she did get into fights with her brothers.

So it's difficult for me to trust her version of the Jamgate, even though I do believe that there was a Jamgate in some form. In my opinion, it reflected the two women's fight over pampering Robespierre - a fight he seemed to ignore (probably as a woman's thing, as if it wasn't happening because of him). As a sister to an unmarried man, Charlotte absolutely had all the rights to be the one to care for Robespierre and his household - it was an important duty that an unmarried sister would do for her brother. In that sense, Duplays overstepped the social boundaries, even if Charlotte was indeed bad at household duties (my theory is that she was too busy with the revolution but I don't have a concrete proof, except my wishful thinking).

Still, it was Robespierre's fault for not saying anything, and for not recognizing the social mistake of the situation. I believe he really felt pampered and cared for at Duplays in a way Charlotte could not provide (if anything, she was one person and Duplays had 4 women ready to pamper him). A different sister might not have cared, but Charlotte was obviously feeling rejected. Couple this with the Northerner vs Paris anymosity and you have a recipe for disaster. Robespierre not solving the situation is not surprising, given his character (I wonder if he noticed anything/knew/understood what's going on), but it's not an excuse, because it was on him to mediate between Charlotte and Mme Duplay, since the whole mess was about him.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The months of winter of the Republican calendar : Nivôse (the month of Snows), Pluviôse (the month of Rains) and Ventôse (the month of Winds) !

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Just Hyping up Robespierre's Speech

Saint-Just, ordinarily rather reserved at the Jacobin Club, made an exception on January 1, 1793. Despite presiding over the session, he didn't share personal views or push his own agenda. Instead, he invited his colleagues to fund the printing and nationwide distribution of Robespierre's second speech on Louis XVI's trial (delivered on December 28, 1792)

His address was probably delivered in a a rather matter-of-fact and perfunctory tone. That being said, in my head, he's going full movie villain on the jacobins, urging them to open their purses or face the "dire consequences from the Archangel of Terror! Mwahahaha!”

(Translation under the cut)

Translation:

Citizens, you are well aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has enveloped the entire Republic, the Society has resolved to print and distribute Robespierre's speech. We have regarded it as an eternal lesson for the French people (1), as a sure way to unmask the Brissotin faction and to open the eyes of the French to the virtues of the minority seated on the Mountain that have been too long unknown. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to indicate this to stimulate your patriotic zeal, and, by emulating the patriots who have each contributed fifty ecus (2) to print Robespierre's excellent speech, you will have well earned the gratitude of the nation.

Notes

(1) The gushing is adorable

(2) In today's terms, fifty ecus translates to approximately 1900 euros. This was no small amount, particularly in light of the country's economic climate at the time.

Source:

Saint-Just, Louis Antoine Léon de. Œuvres. Paris: Gallimard, 2014

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

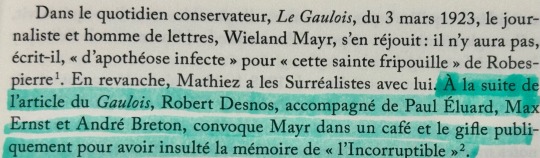

When you get publicly slapped by 4 surrealist poets because you insulted a guy's historical crush

(translation and context under the cut)

Gallantly Defending Robespierre’s Honour

In the conservative daily paper, Le Gaulois, on March 3, 1923, the journalist and man of letters, Wieland Mayr, expressed his pleasure: there would not be, he wrote, a "vile apotheosis" for "that holy scoundrel" Robespierre. On the other hand, Mathiez had the Surrealists with him. Following the article in Le Gaulois, Robert Desnos (1), accompanied by Paul Éluard (2), Max Ernst (3), and André Breton (4), summoned Mayr in a café and publicly slapped him for insulting the memory of "the Incorruptible."

Why did Mayr get Slapped?

In short: studying history in the 1920s was a messy business, especially when it came to the French Revolution….

To explain why Mayr ended up getting slapped, please allow me to briefly dive into the French Revolution's historiography during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Keep in mind, that this is a grossly oversimplified version.

Before 1848, it was pretty standard for French republicans to proudly see themselves as inheritors of Robespierre’s legacy. (If you’ve ever wondered why in Les Misérables, Enjolras’ character is very much channeling Robespierre and Saint-Just, here’s your answer!) However, things start to change with the Second Republic.

In 1847, Jules Michelet brought back the negative portrayal of Robespierre as a tyrannical "priest" and leader of a new cult. This narrative helped fuel an increasing dislike for Robespierre, with radicals like Auguste Blanqui arguing that the real revolutionaries were the atheistic Hébertists, not the Robespierrists.

Jump to the Third Republic, and the negative sentiment towards Robespierre was only getting stronger, driven by voices like Hippolyte Taine, who painted Robespierre as a mediocre figure, overwhelmed by his role. This trend was politically motivated, aiming to reshape the Revolution's legacy to align with the Third Republic's secular values. Obviously, Robespierre, the "fanatic pontiff" of the Supreme Being, didn’t quite fit this revised narrative and was made out to be the villain. Alphonse Aulard (a historian willing to stretch the truth to make his point) continued pushing Danton as the face of secular republicanism. Albert Mathiez, one of Aulard’s students, was not having any of it and strongly disagreed with his mentor’s approach.

The general disdain for Robespierre began to shift after World War I. One reason was that people could better appreciate the actions of the Revolutionary Government after experiencing the repression during the war themselves. Albert Mathiez and his colleagues were actively working to change Robespierre's tarnished image. With tensions high, it's no wonder Mayr ended up being publicly slapped by a bunch of poets who were defending the Incorruptible's honour!

Notes

Robert Desnos (1900-1945) was a French poet deeply associated with the Surrealist movement, known for his revolutionary contributions to both poetry and resistance during World War II.

Paul Éluard (1895-1952) was a French poet and one of the founding members of the Surrealist movement, celebrated for his lyrical and passionate writings on love and liberty.

Max Ernst (1891-1976) was a German painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet, a pioneering figure in the Dada and Surrealist movements known for his inventive use of collage and exploration of the unconscious.

André Breton (1896-1966) was a French writer, poet, and anti-fascist, best known as the principal founder and leading theorist of Surrealism, promoting the liberation of the human mind.

Source: The text in the picture comes from Robespierre and the Social Republic by Albert Mathiez

72 notes

·

View notes