Text

Final Reflection

When I was younger, like – 7 or 8 years old - I got bullied a lot by people; people whom I knew, people whom I knew of, and sometimes just random strangers. At first, I didn’t really know what it was. Was it the way I dressed, with my mother doing her best with the meager income she received from work? Was it because of the flab that hung out of my sides ever so slightly, probably because of the admittedly fatty, but oh-so delicious Filipino food that my father made for me and my younger sister every evening? Or was it because of my tanned, brown skin – a backdrop for my wide, almond-shaped eyes, and a base for my long, black hair that just mopped its way in the front? Or was it because of my Filipino accent, which distinctly separated me from the other kids – the ones who had already found the ins and outs of the social life at school?

In retrospect, and using actual “grown-up” vocabulary, I wanted to feel nothing more than to belong - to assimilate, to be part of the majority. But, one incident that still sticks with me today forced me to understand that I could never – no matter how hard I tried – have this kind of “inclusion”.

I forgot what really initiated it, but during recess this one white kid – I remember his name was Shane – started chanting a string words that I still remember today: “Chinese man, Chinese man, living in a North Korean land” – all the while making “Asian eyes” by pulling them wider with his fingers. In an effort to not escalate the situation even further, I remember just walking away from him while fake laughing.

Yeah, it hurt. And it still hurts a little thinking about it. Still, I use this memory as a means of resistance, as it helps guide and shape my own perspectives as a person of color. I remember that, during section, I was able to be very raw and honest about how this class had helped me realize even further how much I shouldn’t want to be anyone than myself – how being a person of color, being Filipino-American and an immigrant are beautiful intersectionalities, and how my parents bore a heavy burden for me to come and live here in the U.S.

I desire for my own form of resistance to be a sort of dignity and pride, resulting from my memory: For my heritage of delicious Filipino food, the country’s lush, green provinces; for my beautifully tanned, brown skin that definitely separates me from white folk, and the almond-shaped eyes that others didn’t like ‘cause they were so different; for the accent that still comes out when there are too many syllables for me to utter in a single sentence; and for my story as an immigrant who was never from here, but who had to climb mountains in order to belong.

0 notes

Text

Kyle’s Input

Philip’s Zine is about superstition that circulates within primarily indigenous communities. What’s really cool about Phil’s Zine is the variety of examples he uses – from patterned masks, to actual, conceptual superstition that affect the inebriated state of people. Further, Phil connects these examples of superstition and traditional belief to the overarching idea of how all sorts of folks believe in various superstitions. It all connects to the social structures they possess, whether in religion, or identity. Speaking of identity, the Zine touches on this topic and how superstitions reflect the uniqueness of each culture. Also, I think that part of Phil’s argument connects to class. It’s really cool how superstitions and the social class relate to education – and how “educated” certain folks are. I don’t think this is necessarily true, because educated folks can still engage in some sort of belief in a superstition.

“A moko on the face is the ultimate statement of one’s identity as a Māori. The head is believed to be the most sacred part of the body. To wear the moko on the face is to bear an undeniable declaration of who you are” (Media.NewZealand.com)

I think you should talk about the wizard in your final Zine. Definitely expound on class and superstition; this is a really, really good talking point.

As for anecdotes and short stories, I think you could actually still include your original idea of a cornicello. It’d be awesome to actually incorporate some aspect of you are – and your own Italian heritage – into your Zine. You mentioned how it brings good luck in your first Notebook. This would be an excellent segue into other, various aspects of superstitions, ones that you talk about later in Notebooks 2 and 3.

I love the cartoon images you chose for your Zine. They add a playful, but also interesting way of conveying your ideas. It’s cool if you just put them side by side with your text, I think.

Finally, in your last draft for your Zine, it’d be awesome if you could look at the racialized issues surrounding class and education, and how that connects to the superstitions and why people believe in those things. It’d be very powerful to talk about how culture and tradition actually tie closely with racialization – and how these things often play in the power structures of society. Essentially, folks who tend to be poorer usually don’t get the best education. As a result, they place their convictions and beliefs on things that don’t make the most logical sense.

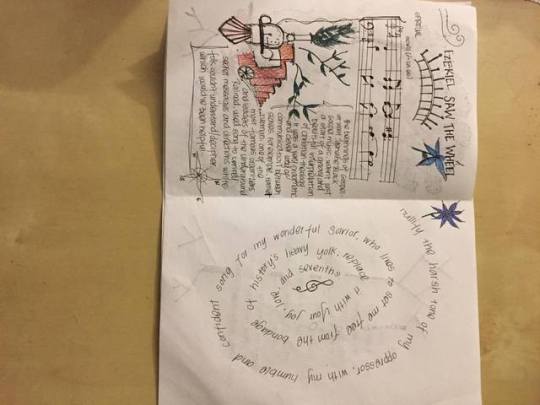

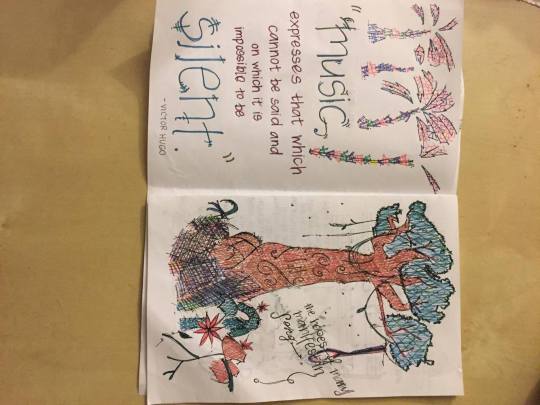

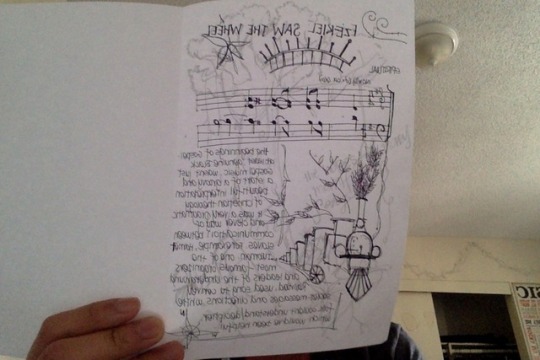

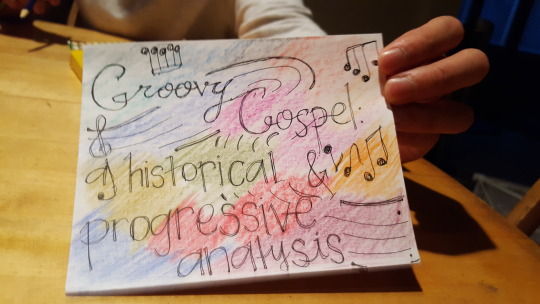

Notebook 4 (Zine pages)

Some of the screenshots overlap, this is not the case with the actual zine, only for posting on Tumblr.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Notebook Assignment 3

Kyle Lorenzo

Monday - 2 p.m.

Boke Saisi

ETHN 2

Notebook 3

I think I really want to incorporate an actual interpretation of the specific songs I use for my Zine, and how these songs connected to - probably - some of the emotions and feelings many artists felt during the time. I hope that this would provide me with a window to peer into a lot of the political stuff going on during the development of the songs. I think it’d be really awesome if I could somehow have the music be a window to more historical strife occurring; but this might be a bit ambitious because the music can just be an art form done by Black folk. However, I want to highlight the beauty and culture – for sure – surrounding Gospel music. If anything, as I progress through the timeline of Gospel music’s development, I’ll add historical context as to what’s going on during the time, though it’d be much more informative if I could actually connect certain songs to things going on during that time period.

For my relational analysis, I want to talk about the ways in which Gospel music has been commodified for the sake of entertainment, primarily through the larger, national market. This has been due largely in part to whiteness creating a way to make money for economic benefit. This has been done countless times, using what Black folk produce for others’ advantage. This relates to the anti-blackness society has so deeply ingrained in itself, and how Black folk have constantly been taken advantage of for their work. For this aspect, I’ll talk mainly about slavery and how Black folk have been taken advantage of for the usage of their bodies, for whiteness’ benefit (i.e. economic betterment). However, I really want to touch on the more present issues surrounding the exploitation of Black culture. For example, many modeling agencies – such as Marc Jacobs – use dreadlocks as a form of fashion for many of their white models. However, when Black folk wear their natural hair, many times it’s seen as unruly and undesirable. This is seen in some more recent news articles explain how school administration wouldn’t allow Black girls to wear their hair in afros or even dreadlocks.

0 notes

Text

Notebook Assignment 2

Kyle Lorenzo

Monday 2 p.m.

Boke Saisi

Gospel music is still going to be my topic for the Zine; since I’d rather speak about it as a whole I’m going to try funneling my thoughts down to certain songs during specific time periods that paint a picture of what’s going on in that part of the timeline. Further, I’d like to use the story of how Black folk created it earlier during the 19th century – when slavery was still present in the U.S. - and how their songs were used especially as a way of communication (e.g. Harriet Tubman, the Underground Railroad). Essentially, a brief but informative introduction will be provided, stating the history of Gospel music – its inception and the ways in which its aided Black folk during the oppression of slavery – and how that has become what it is today. This, of course, can’t be done without digging deeper into Blues, Jazz, R&B, etc. I will briefly touch on these genres as well. However, once all of these larger, general themes are illustrated on my Zine, I’m planning to elaborate on specific songs – older ones and newer ones that fall under the Gospel genre of music (e.g. Break Every Chain for more contemporary Gospel music, A Change is Gonna Come for older hymns). In this way, there will be an overall “feel” of musicality and narration for my project, while at the same time providing

As for the themes of transnationalism and National Binds, I want to focus on how Gospel music has become very prevalent in white culture today. Churches with a primarily white demographic have adopted and assimilated Gospel into their worship services. I’m curious as to see how this genre of music – with its inception beginning in during Slavery – has become so popular within White communities. In terms of transnationalism, Gospel music has made its way from the inner circle of Black musicians and folk to a more diversified audience. Even in my own community, I know of a musician who often travels to Japan to sing and collaborate with Gospel singers! This in itself exemplifies the transnationalism of Gospel music – not just from Black to White communities and circles, but from Black to Asian demographics, too. Looking into the history of Gospel music, after doing some research, I found that there’s actually a bit of a muddling going on. Some historians actually contend that a lot of Black Gospel music roots itself in a Scottish influence; however, the traditional call and response aspect of certain Gospel styles can be found within most African tribes (http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gospel_music). I’m going to dig deeper into this history. Evidently, there are actually two major types of Gospel music – one that roots itself within Black culture, and the other a more white one. Though I will make sure to include information on the white aspect of Gospel music, I’ll be honing in a lot more on how Black folk molded and created Gospel music into their own art. The national bind of Whiteness is definitely present in this topic – as it exemplifies the ways in which whiteness, as a result of its high power within society, has allowed Gospel to become assimilated and commodified as a product presently. Of course, this connects to the ways in which Black folk experience white churches; though they’re able to sing their songs within an accepting community, they still aren’t able to understand their lack of privilege entirely (https://9marks.org/article/why-white-churches-are-hard-for-black-people/). I guess, in addition to how Gospel music has evolved into something entirely different from where it began, I want to shed light on the ways in which Black folk experience church in a primarily white setting. As for a more intersectional analysis, Gospel music… it definitely resounds with race; and even within choirs and communities there are stark differences in the ways in which men and women are perceived and treated. Sopranos and Altos are definitely on the other side of the spectrum when compared to Tenors and Basses – especially within communities of color. How does this feel when power struggles are being experienced in a church and musical setting? This is definitely one thing I want to explore within my Zine, too.

Sources:

(http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gospel_music)

(https://9marks.org/article/why-white-churches-are-hard-for-black-people/)

0 notes

Text

Notebook One

Innumerable items have undergone the process of transnationalization; they didn’t just stay within one nation, but went beyond its borders and traveled many miles via land, air, or sea. However, this sort of phenomenon doesn’t happen solely to physical things. For instance, the ideas surrounding European artwork as being “highbrow” has gone beyond the continent itself and transferred itself over to other countries. Most paintings portraying Biblical scenes and illustrations, or Roman and Grecian gods and goddesses are attached to upper, more “refined echelons” within society – even within the U.S. Very similarly, music crosses numerous borders, exposing itself to ears of folks beyond its place of origin. Gospel music, with its genesis and heart found primarily in the struggle of Black folk during slavery, is one awesome example of such transnationalism.

Gospel music, though originated in the U.S. by Black folk during their slavery, didn’t just stay within this community. The genre of Gospel is a Christian-based kind of music that goes against the regular meter and overall sound of white-based hymns and songs. Instead, it’s very rhythmic; there are a lot of seventh notes within songs – whether on the piano, guitar, or vocals – that add a groovy texture to the quality and perception for its listeners and singers. To me, Gospel makes me want to either sway, snap, and dance in time, or close my eyes and reflect on the simple, but profound message of the songs. As a pianist, Gospel music is extremely difficult to play and to grasp technically because of its rhythmic complexity; there’s a lot of syncopation and diverse chord weaving that goes into properly playing. This is directly because of its relation to jazz and blues: Its origin basically roots itself in the two genres of Black music (http://gospelmusicheritage.org/site/history/). As for the actual transnational aspect of Gospel, I really want to focus in on the early to mid 1900s within the more Midwestern states to today – with Gospel being integrated in numerous churches; for the sake of simplification, I want to focus here in Southern California. Further, I want to see what kinds of churches, especially within San Diego, integrate Gospel music within their services. Arguably, churches nowadays are a lot more liberal in their musical worship – or at least, the ones I’ve experienced. One particular church I’ve been to that beautifully plays Gospel music, as worship is New Creation Church. It was built on top of a hill and accommodates about 725 members (http://www.nccofsd.org/church/). An African American demographic primarily attends the church.

As for the context in which Black Gospel music was played since its origin and where it’s at now – and how transnationalism has allowed it to go where its at today, there’s a lot to say. However, one major difference is this: In the past, Gospel music was used primarily as a form of communication between Black slaves in the context of them finding safety and somehow relaying important messages between one another. These messages usually regarded escape – and were actually known as songs associated with the Underground Railroad. For example, major figures of the Underground Railroad, like Harriet Tubman, used certain songs to give directions to Black folk to help them find escape (http://www.harriet-tubman.org/songs-of-the-underground-railroad/). Now, however, through my own understanding of what transnationalism is – the movement of one object to outside places, communities, and contexts – Gospel music is found in all types of churches amongst different demographics and various kinds of folk. For instance, my own church of Ethnos incorporates Gospel music and plays this genre – and other types of praise and worship – to a diverse congregation; Black folk aren’t the only intended audience.

1 note

·

View note