Text

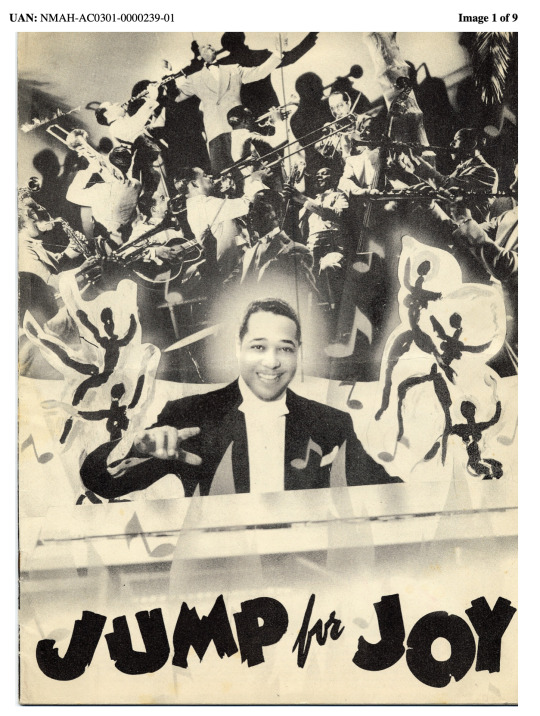

“ …Jump for Joy, a show that would take Uncle Tom out of the theatre, eliminate the stereotyped images that had been exploited by Hollywood and Broadway, and say things that would make the audience think.” — Duke Ellington (^1)

0 notes

Text

Introduction

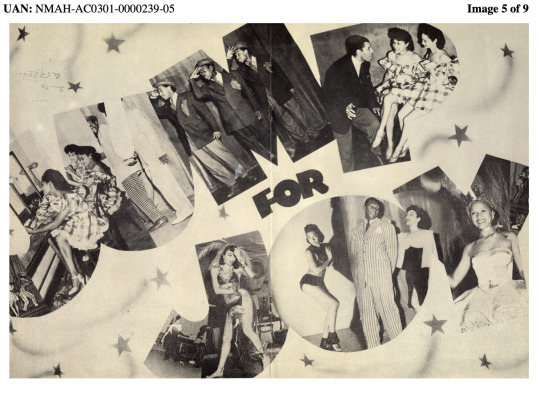

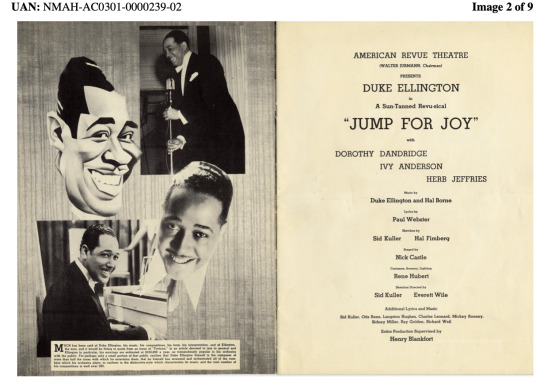

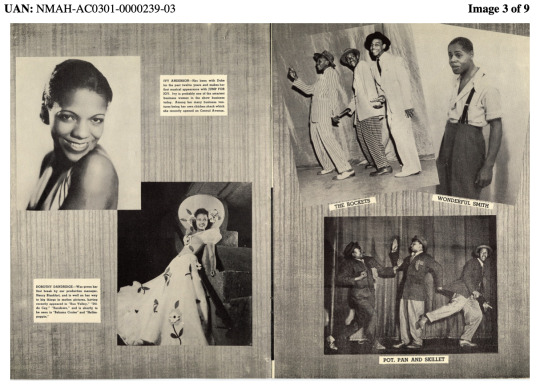

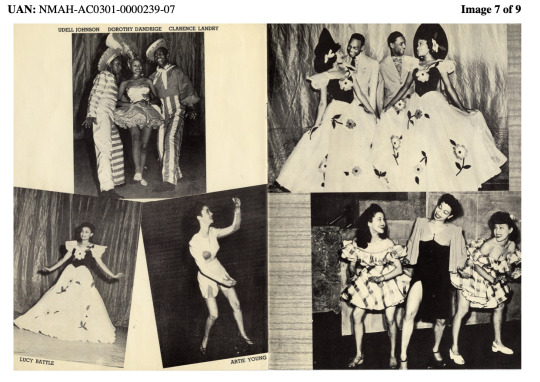

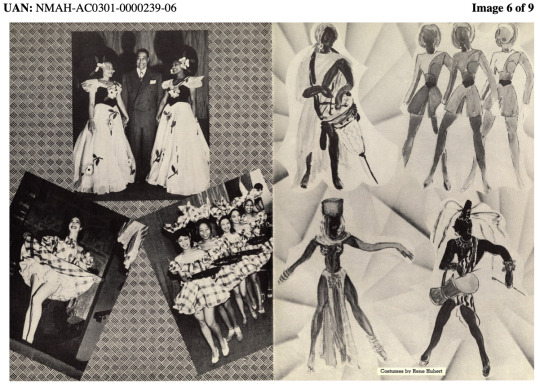

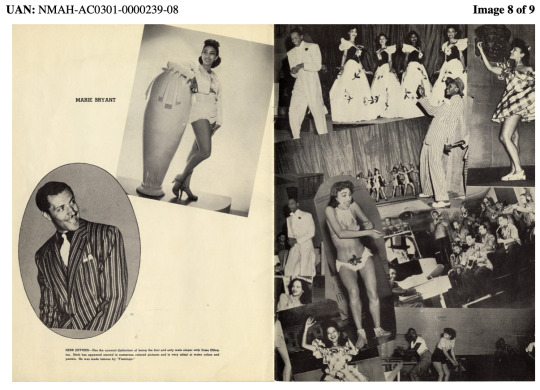

Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Dorothy Dandridge, Langston Hughes, Joe Turner, Ivy Anderson, Wonderful Smith, Marie Bryant — all of these names represent highly accomplished Black artists from the early 20th century, with many of their careers extending past that, and some like Ellington and Hughes even cementing their legacies as household names. And yet, even in more niche circles of musicians, scholars, jazz and theatre aficionados, it is rarely brought up that all of these people once got together to create an ambitious musical revue with an all-African American cast called Jump for Joy. In 1941 Los Angeles, far and away from their home base of New York, Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra collaborated with other significant Black writers, dancers, producers, actors, singers, and performers, to devise a daring example of Black art that broke out of minstrel-esque stereotypes common to its contemporaries. (^2) The show was made possible by interest from important Hollywood executives and creatives eager to fund a show that could not get off the ground on Broadway, names that excited Ellington such as Joe Pasternak, John Garfield, William S. Burnett, Mario Castelnuevo, Ed Fishman, Bob Roberts, George Quince, and Al Barber. (^3)

Ellington was a passionate advocate for racial justice, an ideology consistent with his work and life through its entirety, and the groundwork for it was laid with Jump for Joy. At this particular time, Ellington and his orchestra had reached international acclaim, and the composer was arguably hitting his career stride. (^4) Also in 1941, American government officials were determining their potential place in the increasingly hostile World War II, which would change everything — soon after, many musicians would be drafted, money for entertainment strained, and cultural tastes changed to align with cultural anxieties. (^5) (^6) At home, though attitudes and conditions differed according to location, Black Americans were navigating a complicated reality that followed emancipation from slavery, and thus theoretically should have introduced greater freedoms and a breadth of opportunities, but was actually replaced instead with segregation, Jim Crow laws, and continued instances of racist violence from non-Black people. (^7) Ellington aimed to address political issues pertaining to the Black community in his musical, but more than this, his show as an intensive collaborative effort would demonstrate Black community coming together despite white supremacist efforts to dismantle community and reinforce capitalist ideologies of individualism. The approach to creating a musical that emphasized joy as liberatory is perhaps best exemplified by the anecdote from one of their accidental brainstorming sessions, where Paul Webster brought up his endeavors trying to create an all-Black musical “called Rhapsody in Black, a title no one seemed excited about. But Jump for Joy—that sounded promising.”(^8) From its conception, Jump for Joy was intended to not just replicate and subvert white models of performance (like Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue), rather it was meant to think outside of the box, break out of stereotypes, and bring out good spirits in those who attended. After months of putting together a sizeable cast and crew, tickets went on sale and the show went up on July 10, with celebrities such as Marlene Dietrich and Martha Raye at the premiere. The show was detailed, evidently thoughtful, and saw high audience attendance as a result. (^9)

0 notes

Text

“Everything, every setting, every note of music, every lyric, meant something. All the sketches had a message for the world. The tragedy was that the world was not ready for Jump for Joy.” — Avanelle Lewis Harris, Performer and Cast Member of Jump for Joy (^10)

0 notes

Text

Despite Ellington’s global stardom, his wealthy financial backers, the committed cast and crew, and even the supportive audiences, the state of race relations in America did not allow for a show as progressive as Jump for Joy to continue beyond its 101 performances. (^11) During its brief but impactful run, the Mayan Theater saw an eclectic desegregated audience of notable Hollywood celebrities, middle-class white people, and Black people of varying socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. No matter their status, Ellington observed that his Black audience members “always left proudly, with their chests sticking out.” This was precisely his goal with the musical, a task he did not take lightly, nor did his fifteen or so accompanying writers. They even made it a point to ensure that the show would not offend other marginalized groups, meeting up at the end of every performance to edit or even remove sketches and songs that had sexist, racist, or anti-semitic content. (^12) With such rare attentiveness to proclaiming a message of freedom, happiness, and equality despite difference in political identity, the creators and performers involved with Jump for Joy were breaking boundaries unseen before in the theatre and musical landscape. In consequence, white audiences were often taken aback by the show’s contents, resulting in threats of violence against cast and crew, a main factor as to why the show ended so prematurely. (^13) Externally, the musical had connections with already politically sensitive figures, mainly leftists of the Popular Front such as “Charles Chaplin, Orson Welles, and John Garfield,” all of whom offered and in Garfield’s case ended up providing financial support to the production. Given Ellington’s existing reputation as a “lower-case “c” communist,” mostly supported by his performances for civil rights fundraiser events, but still enough to warrant an FBI file with his name on it, this did not help his cause. (^14) Regardless of Ellington’s exact political allegiance, Jump for Joy was inherently pointing out the irony in America’s pledge to defend democracy and freedom abroad as WWII intensified, meanwhile at home, Black Americans had yet to see the full meaning of said democracy and freedom. (^15) The reasons contributing to the show’s premature run were the same reasons a show as progressive as Jump for Joy was significant and arguably necessary.

0 notes

Text

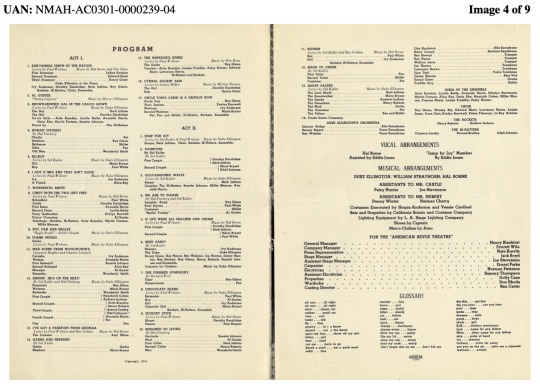

Considering the racist political climate that led to Jump for Joy’s unfortunate end, it almost goes without saying that these issues extended into the lack of preservation and documentation on the musical. In conjunction with the technological limitations of the time, Jump for Joy remains a significant cultural artifact made known to historians close to the subject matter, but otherwise has gone completely unrecognized. US cultural and public historian Benjamin Cawthra writes, “Because the revue did not make its anticipated run on Broadway and no performance made it onto film, and because, in the era before the 33 rpm vinyl record, there was no official soundtrack recording, it is relatively unknown even in the world of jazz. Ellington recorded only a few of the show’s tunes that summer, but their radio life suffered an interruption with a recording ban on radio in early 1942.” In his article, he then ventures to determine how to assess sound that was made and resonated with many, while disturbing many others, but was ultimately not recorded in full. (^16) The purpose of this exhibit is to provide an easily accessible reconstruction of the original Jump for Joy, in order of the program, though as aforementioned, this program was subject to change on every night throughout its hundred or so performances. Through interacting with the various artifacts, one can not only see the fuller picture of a show that of course will never be able to replicated the same way again, but furthermore, will be able to understand the larger cultural implications of a show with such a forward-thinking stance on race in America. Moreover, a look through this exhibit will demonstrate more clearly how Jump for Joy was ‘progressive,’ beyond its reception as such and besides the inference that it indeed was based on who was involved with it. The show balances complicated and heavy sociopolitical issues of racism with levity and tongue-in-cheek humor that serves it well rather than detracting from serious points, while also weaving in sketches and songs seemingly completely unrelated to the topics of race and American politics, instead offering Black audiences Black art about human experiences of love, loss, laughter, sorrow, and above all, joy. The result is a mode of racial liberation and justice that operates at a danceable, up-tempo swing pace, resonating clearly with those who are willing to listen and watch.

0 notes

Text

Sun-Tanned Tenth of the Nation

“After opening with a tribute to the "Suntanned Tenth of the Nation,” the show's spotlight turned to Ellington, clad in tails, who read a statement from his spot in the orchestra pit, according to an account by Ellington historian Patricia Willard. Ellington spoke these moving words penned by Kuller”:

“Now every Broadway colored show,

According to tradition

Must be a carbon copy

Of the previous edition,

With the truth discreetly muted,

And the accent on the brasses.

The punch that should be present

In a colored show, alas, is,

Disinfected with molasses.

In other words, we're shown to you

Through Stephen Foster's glasses.” (^18)

As discussed in the introduction, Jump for Joy was purposefully designed to push boundaries of racial and artistic expectations of the time. Ellington's speech here certainly sets that tone, even without music, though the words and internal rhyme scheme are musical in themselves, such as "truth discreetly muted" and "accent on the brasses." Ellington made a bold statement by referring to Stephen Foster at the end, a minstrel composer known as “father of American music." In turn, the show suggests jazz as true American music instead, made by Black musicians.

The original, early script was actually even bolder, before being removed for its controversy. It opened with Uncle Tom on his death bed, children around him dancing, singing to let him go and have God Bless him. Meanwhile Hollywood and Broadway producers stand looming over him on either side, trying hard to keep him alive by injecting adrenaline into him. (^19)

0 notes

Text

Al Guster — Stomp Caprice

youtube

Early in the show, Jump for Joy featured tap dancer Al Guster, “brilliant in pale chartreuse tails," "while Ellington and drummer Greer emphasized his tapping and reedman Carney underscored his slides and turns.” (^20)

The song as included here, "Stomp Caprice," was a composition “featuring saxophonist Johnny Hodges, as Al Guster tap-danced atop a city skyline. In an early performance, Guster slipped and landed on his rear. In the tradition of the blues, he was down, but not for long. It was a moment of “dissonance” that worked so well the move became part of the routine. In the war years, the cities of the North and the West beckoned with both great opportunity and great disappointment, but as Ellington played his chords and Guster, dancing in a chartreuse top hat and tails, jumped for joy, this Los Angeles story pulsed with the currents of migratory hope and racial pride in a time of uncertainty and war.” (^21)

0 notes

Text

Brown-Skinned Gal in the Calico Gown

youtube

This version is performed by Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra, featuring the listed singer Herb Jeffries, therefore it should be very similar to the original performance from while the show was running.

0 notes

Text

Bli-Blip

youtube

This video is one of the few ‘soundies’ made with Duke Ellington, produced by Sam Coslow, and directed by Josef Berne (R.C.M. Productions), that features original cast members Marie Bryant and Paul White. The sound dubbed over the film was recorded by Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra, also as the original performance. The title screen proclaims “As done in Jump for Joy,” thus assuming that the choreography and staging of the soundie is replicating, if not highly similar to, that of the original stage production. This artifact is one of the closest full-bodied ways we can imagine the original production.

0 notes