Text

Scooters, Shooters & Shottas...

....is a finalist for the 2024 Tinniswood Award - presented to the best audio drama script of the year and sponsored by the ALCS.

0 notes

Text

Yemi & Femi Go Windrush

This is an hour long play I wrote, where my lil' nephews, as I call them, buy a time machine off eBay and go back to a race riot in Notting Hill in 1957, & also meet a couple of Jamaican migrants, Tyrone & Oliver, having a secret affair. We had only 2 days' rehearsal (script in hand) but thank goodness it worked. I managed to twist my back very painfully on performance day & was so distracted I failed to take any production stills for the one-off staged reading at the King's Head, part of Tom Ratcliffe's 2023 Platform festival, which is annoying as it turned out great & everyone had great looks, especially Nathan & J D in their zoot suits & trilbies, & even the time machine prop (using much foil) looked eye-catching. As always, it was a lesson on how few props you need, & how little staging if a story's emotionally compelling. And we got a lot of laughs too! A writer I've worked with was kind enough to call it 'a master class in structure'.

(Cast: Yemi: Dior Clarke; Femi: Mimi Chanel; Tyrone: Nathan Clough; Oliver: J D Hunt; Patrick/Tony/Policeman: Daniel Rainford; Paul/Westfield Customer/Policeman: Will Kerr)

0 notes

Text

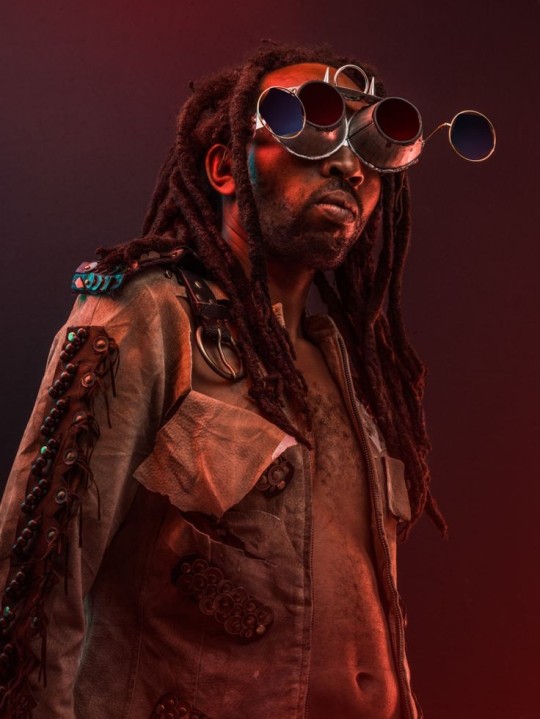

Some behind the scenes photos...

...from the recording of my audio drama Scooters, Shooters & Shottas: a Curious Tale. This took place in one of those interregnums between lockdowns & involved a very nervous group Covid swabbing before we began. Rikki (Beadle-Blair) directing. We began with some grime lyrics I'd written & of course if everyone had thought they sucked, the whole project would have tanked, but thankfully they didn't, & it started to be fun.

Writer / co-creator: John R. Gordon

Director: Rikki Beadle-Blair.

Producer/co-creator: Urban Wolf

Sound Designer: Kayode Gomez

CAST

Kola—Urbain Hayo

Ranksy—Dior Clarke

Bunni Boi—Curtis Lewis

Bigbone / Screw Loose—Romaine Myers

Dunbar—Tristan Jones-Smith

Miz Saltfish / Girl At Party—Jahmila Heath

0 notes

Text

Video interview

Here’s a link to an 8-minute interview with me, where I talk about my novel Hark, and why I wrote it, beautifully filmed (& edited) by Ovi Vil, & produced by Diriye Osman & Isabel Gordon. Do give it a watch if you’re curious...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jqyc771QN1c

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Unquiet Dead & the Deep South

“Dude,” Cleve said, “being real with you: do we need to call an ambulance?”

“The dead don’t need ambulances.”

“So, um, you’re dead?”

Hark smiled tightly. “It’s – complicated.”

— John R. Gordon, HARK

This scene was incredibly fun to write. I don't want to give too much away, but in a story that explores the extreme racial divisions in a dirt poor southern town ravaged by opioid addiction, I wanted to explore an element of the uncanny in a way that added to the narrative. Even though HARK touches on some very serious, and sadly very prescient, themes of inequality, I wanted the book to endow the reader with a sense of hope — especially in these difficult times. For anyone who wants to buy a copy of HARK, signed editions are available exclusively at Gay's The Word bookshop in London, but you can also order unsigned copies globally via this link: https://linktr.ee/johnrgordon

1 note

·

View note

Text

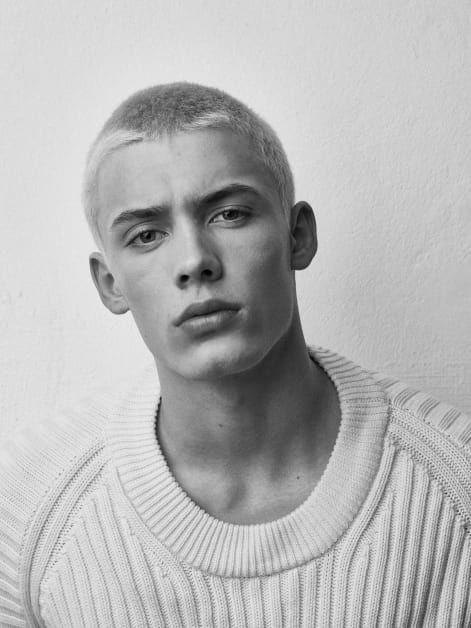

Boy trouble and coming out as gay in your teens...

"Girls would smile at Cleve, who was tall, fit and nice enough looking, but they always wanted the guy to make the first move, which of course he never did – he wanted a guy who made the first move too." — John R. Gordon, HARK

Granted, young people are much more open about their sexuality these days, but it's still quite difficult for a lot of gay teenagers to come out — particularly in small, rural areas like the southern town where this story is set. I wanted to show that not only is self-acceptance possible, but that you can also find love as a young gay man in extremely hostile environments across the world. I hope you enjoy HARK when you get a chance to read it. Signed copies of the book are available at Gay's The Word in London, as well as via the following link globally: https://amzn.to/2SNsPSa

0 notes

Text

‘Hark’, hope, and America’s Racist History

I wrote the first draft of Hark with only a vague sense of how it would end, and more and more as I went along it seemed that the past irrupting into the present was the key theme. If Hark, a black vagrant with seemingly supernatural powers, embodies the violent, tortured, still-clutching racist past, Roe and Cleve, the teen lovers, embody the hope of facing it, getting through it, and moving beyond it. I became certain that the trauma Hark seeks to escape — to transcend — must be tied to both Roe’s and Cleve’s families, in ways that I hoped would beunexpected and thought-provoking. I often think that sort of narrative choice can be specious (eg Blofeldt being Bond’s — I think it’s — cousin in Spectre really doesn’t add any depth or real interest, or I don’t think it does). However, it seemed to me right for the intimacy and tight framing of my novel that bloodlines become entangled with the events of the past.

At the same time, key to making the novel succeed for readers was maintaining a lightness of touch, a vivid sense of the romantic — of teenage desire and burgeoning love in its sticky, complicated simplicity — for older readers; nostalgia though the tale is set in the present. I endeavoured to twine the two together: Hark interrupts Roe and Cleve both literally and figuratively, and at times almost comically. As Roe says, “He’s like some awful uncle who won’t leave.”

John R Gordon is the author of 8 novels, including the Ferro-Grumley Award-winning Drapetomania. He script-edited and wrote for the landmark Black gay TV series Noah’s Arc, and is with Rikki Beadle-Blair co-founder of radical queer imprint Team Angelica Publishing. His new novel, Hark, a haunting tale of gay interracial teen romance that begins the night a Confederate statue is pulled down in a dying Southern town, can be bought here (US) and here (UK). Drapetomania can be bought here (US) and here (UK).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few thoughts on Race, Sexuality, Class and Horror in ‘Hark’

My publisher, Rikki Beadle-Blair, my compadre for over 30 years in many artistic ventures and adventures, always used to say to me, ‘You love horror: why not write a Black gay horror tale?’

I always replied, ‘Because that’s a genre within a genre within a genre: no one would read it.’

I think I was right then, but times have changed since, almost unrecognizably. In The Simpsons cult/nerdish references had to be filtered through Comic Book Guy; in Family Guy they literally ‘do’ Star Wars films for three episodes in a row, just dropping their own characters and a couple of jokes into the re-creation. Meantime, what kid hasn’t read Harry Potter or at least seen the movies? And with the cinematic hegemony of Marvel and DC, sci-fi and fantasy became culturally dominant — not to mention years of Lord of the Rings and then The Hobbit (1, 2 & 3); and with Hunger Games and Game of Thrones fantasy became not only mainstream, but talking point TV.

On the horror front, as well as endless torture porn, there were more intriguing, elegant arthouse-style horror movies coming through — Ringu; Sinister; Insidious etc — and then came Jordan Peele’s masterpiece, Get Out, which was a wonderful exemplar of how one can fuse genre, deep meaning, thrills and genuine provocations into a pacey and alarming whole. His follow-up, Us, proved a horror tale can center a black family in an authentic way while still firmly being a horror yarn.

At the same time Black writers were writing back to the intensely problematic H. P. Lovecraft, who combined a feverish writing style, an intoxicating cosmic regionalism and bleak, oddly compelling anti-theology with a deeply embarrassing and hysterical personal racism. Lovecraft fascinates me, so I was fascinated by these endeavours, which are currently converging in Jordan Peele’s television version of Matt Ruff’s interesting but flawed novel, Lovecraft Country.

So things had converged in the world and in my mind to make me see combining these elements and identities as valid; as something worth doing.

John R Gordon is the author of 8 novels, including the Ferro-Grumley Award-winning Drapetomania. His new novel, Hark, a haunting tale of gay interracial teen romance that begins the night a Confederate statue is pulled down in a dying Southern town, is out on Sept 18th, and can be bought here (US) and here (UK). Drapetomania can be bought here (US) and here (UK).

0 notes

Text

Writing ‘Hark’ against ‘Love, Simon’

When I read the YA novel Simon vs the Homo Sapien Agenda (filmed and later televised as Love, Simon) I found it curious in various ways. Simon is a gay teenager who thinks more ‘above the waistline’ than I would have thought possible for any teenage boy who wasn’t Ace, when contemplating an anonymous online flirtation. This suggested to me, as was the case, a middle-aged female writer.

Okay. Most writers leave traces of themselves within their stories. But what struck me more, and was one of several catalysts for my novel Hark, was what amounts to the (quite lengthy) novel’s denoument. Spoiler alert: having discovered (having never up to this point considered this might be the case) that the unseen boy flirting with him online is Black, Simon essentially shrugs and says, ‘He’s cute, so no problem.’ Despite being teenagers at a school (set rather vaguely) in the Deep South, neither he nor his paramour have any thoughts whatsoever about what dating — desiring — loving across the races might mean. Simon having had no romantic thoughts about — having really not noticed — any of the Black boys at his school, then has no thoughts about having a Black partner either. There are no revelations, no insights, no challenges. The novel ends at the author’s limits of knowledge, or so I’d guess: having no Black friends; having never, I would suspect, been in a Black person’s house, she could write no farther. And so it closes around exactly when I thought it ought to have got going.

I thought I could do something different — something the literal reverse, in which all must be seen, and faced, and like the fire passed through. And so Hark opens with the take-down of a Confederate statue, and a meeting between a Black boy and a white boy on that strange, violent, racially-saturated night.

To misquote the strapline for the Bond movie Moonraker, ‘Where Love, Simon ends, Hark begins…’

Buy Hark here (US) and here (UK). Drapetomania can be bought here (US) and here (UK).

0 notes

Text

How Audre Lorde’s Radical Feminism Changed Me

Very late one night a couple of years ago I found myself urinating dark, goopy blood. Alarmed, I called NHS Direct. As I didn’t have a GP, I was advised to go straight to Hammersmith Hospital, which is by Wormwood Scrubs, and not in Hammersmith. Anticipating a long wait, I shoved a book in a bag and cycled over there. It turned out to not really have an A&E department, but after sitting in a deserted, low-lit waiting room for half an hour – during which time I became increasingly nervy as my bladder filled enough for me to give a sample – I was seen, rather grudgingly, by a doctor much like Dr Now from the American obesity show, My 600lb Life. He scolded me for not being registered with a GP, but then kindly arranged an immediate blood test for me. The catch was, it was at Charing Cross Hospital. CCH isn’t in Charing Cross; it’s in Hammersmith. So I cycled down there, thinking of cancer, and dying just when my new book, Drapetomania, was in the running for two awards (one of which, the Ferro-Grumley, it went on to win.) They took my details, more treacly rust-coloured urine, some blood, and left me to wait.

I dug out the book I had brought with me. It was a slim collection of letters between Audre Lorde and fellow Black lesbian poet Pat Parker titled Sister Love. Though the letters were interesting and touching, my choice was, I quickly thought, a mistake, as both women battled, and ultimately succumbed to, breast cancer, and their letters shared this struggle and burden. Or perhaps it wasn’t a mistake, as what they shared landed on me as vividly as it was ever likely to do. My wait was lengthy, and during it I read the entire short book.

Audre Lorde is one of three Black feminists who have made a particularly powerful impact on me, and she perhaps settled deepest within me, though I came to her last.

At Leeds University in the early 1980s I studied a strangely hardcore form of Marxist-Structuralist early Third Wave feminist art history under the now-legendary Griselda Pollock. This was just before the rise of post-colonial studies and, while there were nods towards issues around race on my course – something I was investigating deeply in my private reading of Baldwin, Wright, Himes, Ellison and various other Black radical thinkers and activists – it was never a central concern.

By chance, browsing in the library, I came upon bell hooks’ Aint I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, and borrowed it. I guess this became my first intersectional reading, and I devoured it eagerly. I went on to Angela Davis’s Women, Race and Class, and found that full of insights too – of course I’d learned of her while reading George Jackson, Baldwin, Huey Newton and others: America’s Most Wanted, with her trademark Afro. After struggling along with difficult post-modern theorists – Foucault, Baudrillard, Bhaba, Spivak etc – it was an incredible relief to read work that was clear, purposive, jargon-free and, while certainly intellectual, accessible and excitingly engaged with the world.

I’d first heard of Audre Lorde as a poet, but started to engage with her thought after reading a rather awkward conversation between her and James Baldwin: as with his longer conversation with Nikki Giovanni, it was in part a generational clash, or divide; in part about sex, gender and their meanings. This led me to read Lorde’s classic automythography, Zami, and then her intensely moving Cancer Journals and A Burst of Light, along collected interviews, essays and articles (mostly in Sister Outsider); and I later read the excellent biography by Alexis DeVeaux. Warrior Poet (now finally back in print.) Her insights were pithy, complex and concise. Check this out:

“Black women have on one hand always been highly visible, and so, on the other hand, have been rendered invisible through the depersonalization of racism.” (Sister Outsider)

Lorde inspired me by the particular courage with which she lived her life, determined always to bring her whole self to any room she happened to be in, whether that made other people – and indeed herself – comfortable or not. ‘I am a black lesbian raising a son, in a relationship with a white Jewish woman’ was not an introductory remark that guaranteed a person a warm welcome in the late ’70s or early ’80s, even in radical circles; and nor did it. For her intersectionality was a lived, and a living thing – a warm and embodied thing – as well as an intellectual position. The personal was – is – political. As a white gay man in a relationship with a black man, she crystallised many things for me in a vivid, challenging and deeply humane way.

As an artist, she said, “When I dare to be powerful, to use my strength in the service of my vision, then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.” Though this formulation is unique to her, still I find it speaks strongly to me, as do many other things she said. Thank you, Audre.

Seven hours after I had first pissed blood, and mercifully cleared of fears of cancer, I stepped out with hard, tired eyes into the dazzling, commuter-crowded morning.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why James Baldwin Matters Now More Than Ever

James Baldwin is now so culturally centered, so quoted, so lionized – even if often still denuded of his sexuality (consider Raoul Peck’s recent documentary I Am Not Your Negro, where the only references to Baldwin’s sex- and romantic lives are an FBI ‘rumor’ that he ‘may be homosexual’, juxtaposed with a straightwashing quote from the writer himself, about a youthful affair with a white girl being stifled by societal racism) – that it is hard to recall he had a stretch of being wholly out of favour.

It’s sad – upsetting, even – to see how rising-star heteropatriachal Black Power activists headily disdained him – Eldridge Cleaver; Amiri Baraka (with whom he was later to become friends) – while white critics and reviewers dismissed his later novels, Tell Me How Long The Train’s Been Gone and Just Above My Head – in my opinion his best work – as ‘bitter’ because he critiqued the failings of the Civil Rights movement, and of the white liberal establishment; because he had lost hope in white people reforming themselves – had lost hope in their ability to see that in that reformation lay liberation from their own pain.

I never got to meet James Baldwin in person, but a friend of mine, Philip, a gay, fey, (then young) Jamaican did. Baldwin was over in the UK for a revival of The Amen Corner, his powerful, incisive and surprisingly funny play about the social dynamics of the Black Church in which he had grown up. This would have been in the early eighties – Jimmy transitioned to the ancestors in 1987 – when his status as a writer was at its lowest ebb.

He came into the Soho bar where Philip was working as a waiter, and my friend experienced one of those moments of cognitive dissonance where you are dazzled by the appearance of a legend and nobody else even knows who that person is, never mind that they’re a big deal. The other staff members were white, and Baldwin was clearly gratified to be recognized by a fellow black man: to be made to feel – to be acknowledged as, as my goodness he was – special.

He endured long enough to become friends with some of his harsher 60s and 70s critics – Baraka; Ishmael Reed – and see the fall into ludicrousness of others (Eldridge Cleaver turning evangelist and failed Republican candidate), but not long enough, of course, to witness his own current apotheosis through social media. A man who fused the stylings of hellfire preaching with fey urbanity, he was, quite simply, charming, and so the many videos of him in interview and discussion are still intoxicatingly striking today.

Which would of course be nothing without the words – and what words! And how eerily, presciently, alarmingly applicable to our present moment, our present crisis, those words are.

Well, so many have written about him, and eulogized him, far better than I. Today I want to think about the lessons he offers artists who are also activists – something I hope in my quiet way I am – both in terms of what I write about, and how; and as I do my best to uplift and empower those shunted to society’s margins – most particularly black and LGBTQ writers and artists.

For all of his adult artistic life, Baldwin, who as a teenager had been stretched taut between the pulpit and the world, was stretched between the inwardness of writing – I’m thinking here particularly of his fiction, and fiction requires a withdrawal, a going within – and the outwardness of his Civil Rights activism (in which I would include much of his writerly reportage).

These corollaries – for I think it misleading to call them oppositions, exactly – seem to me to be interlocking parts of an artist’s duty: to his fullest realization of himself as an artist (including, at least notionally, the ultimate liberation from feeling compelled to express autobiographically identity-centered themes) and to the artist’s duty to, as Jimmy put it many times, witness. To not shrink back from, or disengage or shy away from, the world as it is, in its wonder and horror.

As Nina Simone, a friend – or perhaps more truly a comrade – of Baldwin said, “An artist’s duty, as far as I'm concerned, is to reflect the times. I think that is true of painters, sculptors, poets, musicians. As far as I'm concerned – it’s their choice – but I choose to reflect the times and situations in which I find myself. That, to me, is my duty.”

Always there was a lack of time to write; often a shortage of money. Baldwin would retreat to get a novel done – then instantly sabotage himself by letting friends know where he was, unable to resist sociability. And they would appear, and the party would begin, and he was there till the end. But still he got his work done: after everyone else had drunk themselves into a stupor, or dozed off exhausted in armchairs, or collapsed into bed, alone or in company, he would sit at his typewriter as the dawn came up, and do his work. And if no one would call that a healthy routine, and I doubt any artist really has a healthy routine, he did get his work done.

I don’t have a thesis for this article. Maybe it’s just a praise song, sung slightly too late, on the occasion of the anniversary of Jimmy Baldwin’s birthday, August 2nd, 1924.

0 notes

Text

How to beat writer’s block

I don’t, by and large, suffer from writer’s block – don’t subscribe to it as a particular psychological malady (in fact I think it’s unhealthy to fetishize it in that way, because to do so can in and of itself generate paralysis). However, when I do get blocked – or perhaps I’d rather say held up – it’s usually because the project is too vague, too embryonic to be born yet, but a deadline has cropped up – either for some funding stream or other, or because someone else involved in the project is suddenly keen to drive it forward. So, as suddenly, one is obliged to produce, and it can feel like there’s nothing to draw on; nothing inside. You said to someone that you’d write some tale about x, and now it comes to it, you have no ideas, or at least nothing that needs to be expressed.

How, then, can you get the egg implanted in the womb-lining, and urge the gestation along in a way that avoids mental miscarriage, dispiriting prolapse, or a morass of birth defects cropping up as you attempt to force the development? What is a fast way to break through so-called writer’s block?

One technique I’ve always found to be helpful is to set aside the computer (or nowadays phone), go somewhere pleasant with a pad and pen (for instance, in this weekend just gone’s oppressively humid blaze, my local Costa coffee, which has aircon as well as boisterous Somali chatter filling the cooled air).

Avoiding internet distraction, and as far as possible without thinking consciously before you begin, (try not to even think, ‘Now I begin’), start to write a literal stream of consciousness. Exclude nothing, even such a thought as ‘I don’t know where to start’. Include questions, images, thoughts and observations, snatches of dialogue, phrases, notes to self, irritations and resentments. Don’t go back or reread; only write forward. Don’t revise, don’t judge; just keep moving. Ignore contradictions: decisions about those can be made afterwards.

Don’t try to write well. Put down voices as they come to you. Their register needn’t be fully achieved. Just keep going until they start to evolve into particularity. Flow without reflection from prose into dialogue and back. Consistency doesn’t matter. The important thing is to be in the moment: to not be looking on as ‘a blocked writer’: you aren’t blocked because you are putting down words. There is no ‘you’ holding things up with judgments or self-doubt. However messy and diffracted your thinking, however many dead ends you venture up – so what? You’re on the journey. If an alley is blind, forge on in a new direction instantly. Don’t cross anything out – don’t waste the time. Put a question mark after anything doubtful. If something seems helpful write ‘yes’ after it or in the margin. Add feelings as prompts – ‘I like this’ or ‘could be good but boring here’ – and move along.

You will meet challenges. For instance, an honest thought – which you should, as above, write straight into your stream of consciousness screed – might be, ‘I don’t care about these characters or this situation one bit’. Again: don’t judge, don’t cry about it. This is a revelation, not a block, because having understood it, the next thought is: what would make me care? Are they the wrong sex, sexuality, age, race or any of a zillion other variants? Are there changes you can make within the context in which you are working (for instance the constraints of a low-budget short film, a current project of mine) that will make you care?

Sometimes, it’s true, the revelation, the ‘unblocking’ will be that you should abandon the project. This, though irritating, will at least draw a line under your suffering and liberate you to put your energies somewhere more productive. However, my usual experience in using this method is that one starts to break through to a story – a situation, a collision of characters and themes – that one does care about. That is writeable.

So don’t stop: keep covering the pages. Almost invariably you’ll find yourself getting somewhere: suddenly generating things you respond to on some level – narratively, maybe; or intellectually, or emotionally. Out of the blue you’ll have a scene – probably a middle scene, but it’s likely to suggest – or logically or emotionally compel – an end or a beginning – something to join onto it, to get you moving backwards or forwards within your story. Keep going until you are written out. Then set the scrawl aside and do something else.

Later on, write up what you put down. I usually do this the next day. Because you will have got somewhere by the end of the process, you’re bound to feel cheerier. Now you can assess the value of earlier thoughts and observations: you’ll be able to see what you can in retrospect slot in; what discard. As you boil it all down, and shift elements around to where you begin to see they should fit in your narrative, you will find yourself moving towards at least an outline – hopefully one populated with the beginnings of characters, situations, psychology and aesthetics that interest you enough to become excited: something from which you can write forward.

John is the author of 8 novels, including the Ferro-Grumley Award-winning Drapetomania. His new novel, Hark, a haunting tale of gay interracial teen romance that begins the night a Confederate statue is pulled down in a dying Southern town, is out on Sept 18th, and can be pre-ordered here (US) and here (UK). Drapetomania can be bought here (US) and here (UK).

0 notes

Text

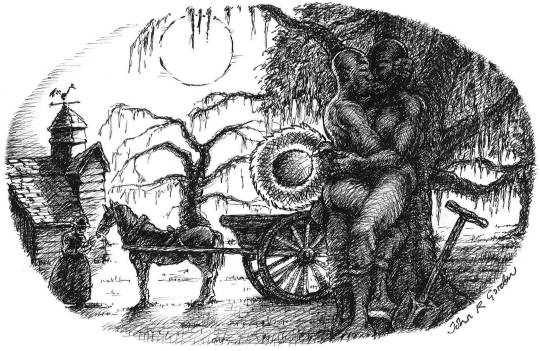

Thoughts on Christianity and Homosexuality under Slavery

My 2018 novel, Drapetomania, is an antebellum epic that follows two enslaved Black men, Cyrus and Abegnego, who become lovers. After a flood threatens to bankrupt the plantation on which they toil for the benefit of their enslavers, Abednego is sold away. Broken-hearted, Cyrus makes the momentous decision to flee the plantation on which he has spent his entire life, and attempt to seek out his lost lover: his true north star.

One premise behind my writing the novel was to use fiction to restore to life and to cultural memory the sorts of lives that passed unrecorded. For of course no-one wrote a gay/sgl slavery narrative in the C19th — such an endeavor would be almost, if not entirely inconceivable. Following the advice of Toni Morrison, I wrote the book I needed to exist.

While responses to the novel have been overwhelmingly positive, an interesting critique came my way from a (white gay) reader, who found my representation of the lack of guilt and shame Cyrus and Abednego feel over their sexuality and relationship unrealistic. Why, he asked, do they not writhe in the self-loathing that would have been, and has continued to be, planted in gay men by conservative Christian moralizing? Certainly there would be no countervailing liberal or progressive tradition to which they would have any sort of access.

I found the charge interesting: had I, as a gay man, been guilty of sentimentality? Given the years of research I had done in order to render a realistic portrayal of various experiences of chattel slavery and the psychology of its brutality and oppression, had I stumbled here, out of the impulse to allow my characters an implausibly heroic mode?

I reflected, and on consideration decided I had not. In fact, I concluded that my critic was guilty (as it were) of his own particular anachronistic thinking. He took the current Evangelical fixation with homosexuality as the singular locus of moral depravity (much worse than murder, adultery or stealing) and projected that current cultural centrality 170 years backwards into the past. I don’t think contemporary reactionary Christian concerns map onto previous centuries tidily. The feverish religious homophobia of today has gained its focus through LGB people asserting their rights on identitarian grounds analogous to those identities based on race (and so modeled on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements) and gender (feminist movement.) That recategorization removes sexuality from the religious frame altogether — moves it away from sin — and Evangelicals are much exercised trying to claw homosexuality (and its kin) back from the world of human rights based on identity, and into sinfulness. It’s this categorical escape (or refiguring) that drives contemporary religious homophobes mad, and leads to them positioning themselves as victims of a supervening, ‘bullying’ secular discourse.

None of that pertains to the world of America in the 1850s, when Drapetomania is set; a time when by and large ‘homosexuality’ as an identity had not been conceptualized — or certainly not beyond the figure of the performatively effeminate Sodomite (whose ‘freakish’ disordering of gender roles also prefigures later trans discourses). It seems to me unlikely that Cyrus or even the somewhat more worldly Abednego, would have experience of such a person or knowledge of such a concept — and would certainly not see themselves as represented or embodied by it/them.

I think one can also ask, what would have tended to be the focus of the Christian preachers and teachers of the time, in terms of the lessons they sought to impart to the enslaved flock? The historical record is informative. With the exception of active abolitionists, (who could expect to be beaten, tarred and feathered for their efforts), white preachers focused on how slaves should obey their masters, render unto Caesar, set little store by acquiring worldly goods, and endure ‘unimportant’ earthly suffering in anticipation of far more important heavenly rewards. Going forth and multiplying was another tenet, though as an ‘animal’ function it was deemed not to need emphasizing.

What would these white preachers have said to the enslaved about sexual morality? First one might ask, would the enslaved have paid serious attention to anything they said, given the exploitative nature of slavery, and the defenselessness of the enslaved in the face of sexual predation and violence. Any sermonizing on sexual morality would surely have been viewed most ironically, and not be seen as having any moral weight.

Moreover, in such a context, without a trigger or catalyst — that is, an event publicly noticed — why would a white preacher bring up the sins of Onan or Sodom? The pseudo-scientific race discourse of the times gave rise to the notion that ‘Negroes’, being closer to the brutes of the fields, were ignorant of the possibility of sexual ‘deviance’, it being a product of perfumed decadence. Why chance planting such decadent ideas in pliant minds, however limited those minds were assumed to be? Better to say nothing. Better to urge marriage, however little it would count for; to urge reproduction.

What, then, might enslaved preachers preach among their fellows? This, of course, is much less recorded. However, we can reflect on its likely focus. Here a guide is surely sorrow songs and spirituals, imprecating the Lord to ‘let my people go’, drown Pharaoh’s army, and liberate the Children of Israel from slavery. Talk of a Promised Land that for white preachers was located conveniently in the hereafter, was a way for Black preachers to model liberation for other Black folks, share notions of a better life, and even outright rebellion: the North might be at least a version of that promise.

Given the vicious (and vastly predominantly heterosexual) sexual oppressions of slavery, pious talk of sexual morality amongst the enslaved must have dwelt in an ambiguous, uneasy realm, and in the slave narratives, and the sermons at times mixed in with them, we see talk of loving friendship and support between man and woman, husband and wife, championed as key virtues. Within this matrix, it seems to me inconceivable that homosexuality — in particular the tale of Sodom and the strictures found in Leviticus — could be in any way a focal point of sermonizing. It could only conceivably become so as a consequence of homosexual relations occurring in some measure publicly, within the immediate environment.

Indeed, it’s at that point in the novel — when the intensity of the friendship between Cyrus and Abednego becomes noticed by the other hands — that Samuel, the slave preacher with whom Cyrus shares a cabin, hints at the issue. However, he references the tale of David and Jonathon, rather than that of the Cities of the Plain. To his question, is Cyrus and Abednego’s relationship like that of David and Jonathon, Cyrus simply replies yes, and is sufficiently imposing (and indeed well liked enough) to foreclose further comment.

I felt that was realistic. Samuel is confronted by two people he has known all his life, and so the Bible tale he goes to is one about two individuals, rather than the tale of Sodom, with its fairly unrelatable power dynamics — stranded wanderers; a lynch mob of locals — its peculiar aspects (handsome angels as houseguests), and queasy foundations (‘Rape my daughters instead,’ Lot offers) that could hardly have sat well with an enslaved man who has witnessed such sexual violence against women at first hand.

Cyrus and Abednego, then, in somewhat differing ways (Cyrus being at heart a pre-Christian animist, and Abednego anticipating the modern secular man to whom religious doctrine is marginal), both inhabit the tale of David and Jonathon’s loving friendship, and find no reason to connect their experience with the tale of Sodom. I think here love is key. It is love that reveals their desiring natures to both each other and themselves, as opposed to experiencing a desire to perform certain sexual acts with someone of the same sex, and seeking out someone who responds to that desire — though the more worldly Abednego is more aware of a desiring identity as a possibility, prefiguring modern conceptions of self, than is Cyrus, the novel’s primary protagonist. Cyrus’ sense of identity formation is brought into sharp focus later, through his encounter with the white coachman, James Rose.

And so I think my interpretation stands. But it was deeply interesting to be given a reason to reflect upon it at length.

John’s new novel, Hark, a haunting tale of gay interracial teen romance that begins the night a Confederate statue is pulled down in a dying Southern town, is out on Sept 18th, and can be pre-ordered here (US) and here (UK). Drapetomania can be bought here (US) and here (UK).

1 note

·

View note

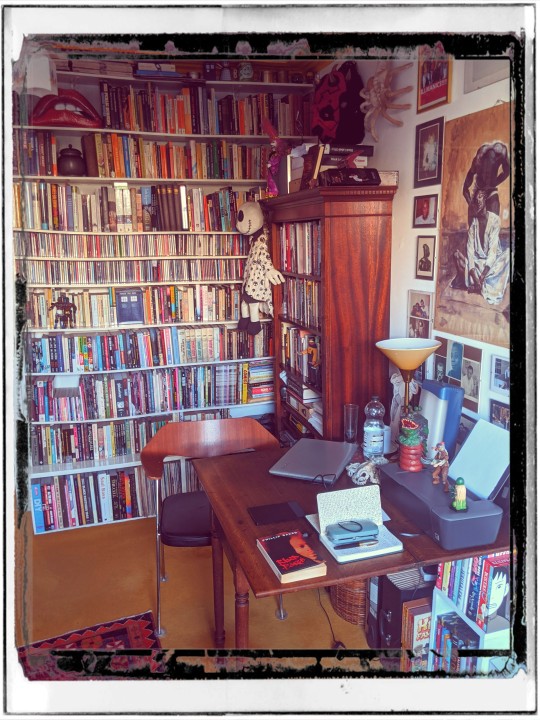

Photo

My other workspace (the one that gets the afternoon sun, when there is some.) Cups & plates by Clarice Cliff. Hot cross bun by M&S. In the lower image, art for my upcoming novel, Hark (preorder here (US) & here UK).

0 notes

Photo

My living room, which is also my study... (photo by Diriye Osman)

0 notes

Text

Writing a historical novel #20 – fantasy versus history in fiction

For the past ten years I have been working on a historical novel, Drapetomania, Or, The Narrative of Cyrus Tyler and Abednego Tyler, lovers, set in slavery times in the American Deep South, and telling of the passionate love between two men, Cyrus and Abednego, and their bid for freedom from bondage – out now. As I worked on a final edit of the 183,000 word manuscript, I began reflecting on the process. These are some of my thoughts.

While re-re-rewriting Drapetomania I nervously read Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of slavery and escape, The Underground Railroad (2016). My usual worry: what if he, a far better-known and well thought of author, had used some scenario or other I had, but had done it much better?

I struggled with UR’s central fantastical conceit – that the underground railroad is a physical, mechanical railroad running through tunnels under the ground, rather than a network of historically real people offering (at risk to their own lives) assistance to runaway slaves – and its numerous anachronisms (around such matters as forcing tubal ligatures on African-American women – a form of surgery that was not to exist for another 75-odd years – and transposing the criminal Tuskegee syphilis experiment backwards in time) off-putting, because I didn’t really see why the author had so cavalierly distorted & indeed overwritten historical reality.

To me this, like the counter-factual Tarantino flick Inglourious Basterds, undermines the real heroism of the times in which it is set, and risks being a sort of erasure. IB, like Django Unchained, seems to exist to present Tarantino’s fantasy that if black slaves, or Jews under the Nazis, had only mustered a bit of (white Western-style) two-fisted shoot-’em-up grit, then slavery and Nazism would have been briskly overthrown. This I think is contemptible.

Whitehead is doing something very different, of course, but to me his novel falls into the error of thinking the blatantly made-up more interesting than the historically grounded – and overwriting real courage and danger with fantasy, which seems to me an accidental immorality, somewhat akin to saying aliens, rather than human beings, built the pyramids. To which he might say, of course, ‘Where’s your Pulitzer Prize?’

I felt particularly aware while writing Drapetomania that presenting horrors more extreme than anything in the historical record (which is in any case extreme enough) would pull the book into fantasy territory, and therefore make it on some levels unserious, merely gross, discardable.

Interestingly, reader responses to The Underground Railroad (on Amazon, anyway) were sharply divided: either one found the central conceit bold and intriguing or annoying and pointless.

Those hundreds of reviews were also salutary in reminding me how many people know a really considerable amount about history of every sort – including such minutiae as when elevators were first in use; how many storeys the tallest buildings might have been in 1850 and so on. But the book, the prize and the reviews were all heartening reminders for me in terms of my own endeavour that the subject remains vivid, and that it is something people are at least prepared to engage with in radical fictional form.

There is something liberating in a writer successfully showing that representations of historical trauma need not be forever tied to naturalism, to the near-documentary – a persistent imposition on historic slave narratives, which tend to be valued for their (presumed) factual content more than their literary qualities – and on African-American (and indeed Black Diasporic) writing in general.

Writing a historical novel #21 – narrative point of view

Drapetomania is divided into three books – Cyrus’ viewpoint; Abednego’s; and a concluding, much shorter part when they are reunited. In the main I hold strongly to seeing everything strictly from each character’s viewpoint, though as the narrative is third person indirect I can name things they would not know by name – a mantelpiece made of ormolu, for instance. Here and there I expand into a wider sense of what they – enslaved black people – feel and think within the narrative, and what the white slavers think and feel too (this latter, however, only comes in through the eyes of the black characters, so white-mindedness remains their – the black characters’ – perception of it). I wavered over this, because it can be a narrative cheat to suddenly bring in a detachedly omniscient voice (Agatha Christie’s a particular offender, jumping into viewpoints and out again, but suppressing whole chunks of their thoughts to keep the plot going without revealing the killer’s identity), but considered that, done right, such shared perceptions realistically embody a shared mentality and, implicitly, show a spirit connection, and I developed them in that light, magnifying an early theme of shared dreams, and building to the need for group resistance as well as a traditional, grandly romantic upsweep towards the novel’s resolution.

Writing a historical novel #22 – coda

I came across Hilary Wolf Hall Mantel’s Reith Lecture the other day, and in discussing writing historical fiction she said, ‘The moment we are deceased we become the subject of stories. The process of fictionalisation is instant and natural and inevitable.’

In all cultures the past becomes mythologised, and myths of origins are created. It’s because of this aspect of the human mind that fiction works at all, and that historical fiction can be successful.

And all the writer can do is write with such integrity, intelligence, wisdom and grace as s/he can muster.

Buy Drapetomania here and here.

0 notes

Text

Writing a historical novel #19 – period dialogue

For the past ten years I have been working on a historical novel, Drapetomania, Or, The Narrative of Cyrus Tyler and Abednego Tyler, lovers, set in slavery times in the American Deep South, and telling of the passionate love between two men, Cyrus and Abednego, and their bid for freedom from bondage – out now with Team Angelica Publishing. As I worked on a final edit of the 183,000 word manuscript, I began reflecting on the process. These are some of my thoughts.

As well as the general question of how to represent period speech, there’s a particular issue with representing the speech of black folks back in slavery times – especially those who are uneducated. How did they really talk? There is a very artificial, derogatory ‘coonshow’ idiolect that crops up in vulgar/popular representations well into the second half of the twentieth century, where among other things ‘v’s are generally replaced with ‘b’s.

This version of dialect, which is painful to modern readers because it’s so strongly associated with a plethora of viciously racist caricatures, is used not only by white writers of the time (that is, pre-Civil War) but also in slave narratives by African-American authors who are more educated (or ‘cultivated’) than average (& are educated enough to write their own accounts, rather than being written up ‘as told to’ some well-meaning white person with his or her own agenda). Was this stylization, grating to any modern reader, used because of white editorial interventions, or was it a choice by the black author to follow established conventions for representing uneducated black vernacular? Or – whatever its associations for us now – were (at least some of) these conventions how people really spoke? These stereotypes must, after all, have arisen from some perceived speech patterns that evolved amongst enslaved Africans denied their mother tongues – some shared linguistic commonalities.

Since one is writing for a modern reader, however ‘in period’ one wants the novel to feel, I strove to avoid use of period dialect that would be distractingly uncomfortable to read. To me what was most important – apart from vivid phrasing generally – was to create a hierarchy of speech that marked class and status, with those in the Big House tending more closely to adopt the linguistic patterning of the white folks of the time. I also attempted to include intentional shifts in register, to mark the difference when black characters talk among themselves as opposed to how they perform language in the presence of whites.

To present dialect – historical African-American Vernacular – as a legitimate form of language, I decided to use a minimum of apostrophes to mark abbreviations or contractions. I hope this will quickly come to read naturally.

Buy Drapetomania here and here.

0 notes