Text

The Scopes Trial: A Controversy about Evolution

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

March 6, 2024

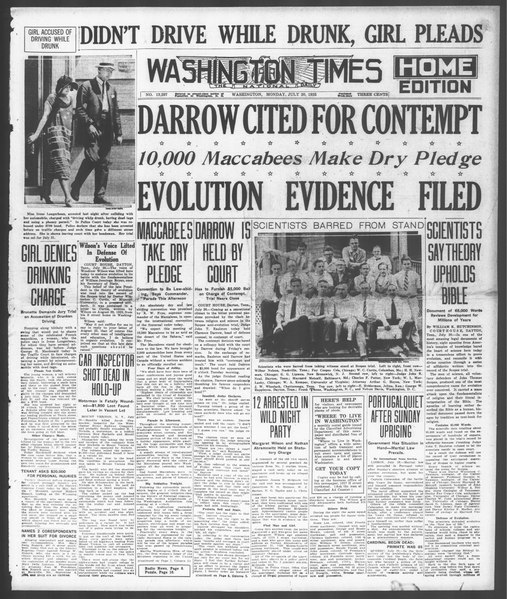

The Scopes Trial refers to John Scopes, the defendant, who was convicted and fined $100 for teaching evolution in a public high school. Central to the case was the Darwinian theory of evolution and Biblical literalism that gave rise to fundamentalism. The defense team was led by Clarence Darrow and included John Neal, George Rappleyea, Arthur Garfield Hays, and Dudley Field Malone. The prosecution included Tom Stewart, Ben McKenzie, and William Jennings Bryan. Both Darrow and Bryan came to represent two sides of the trial, Darrow stood for academic freedom–which included allowing the teachings of evolution–and challenged the religious and moral views of fundamentalists.[1] Bryan, on the other hand, was seen as the leader of fundamentalism and, thus, a threat to individual liberty because he wanted the state and its people to control the curriculum of public schools, effectively barring teachings of evolution.[2] And while Darrow claimed to be an agnostic, he was actually an atheist who viewed Christianity as a slave religion and its teachings as dangerous.[3] As such, the ACLU–American Civil Liberties Union–was wary of having Darrow on the defense team, believing that his zealous agnosticism would transform the trial from an appeal for academic freedom to a broad assault on religion.[4] This, of course, does end up happening later on in the trial. Bryan, on the other hand, occupied more of an honorary role in the prosecution, his presence attracted spectators and, eventually, led to his notable exchange with Darrow.

Within the actual trial, the exchange between William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow became legendized. Arthur Garfield Hays was the one who called Bryan as the defense’s final expert on the Bible, putting him on the witness stand.[5] Darrow then took over and questioned Bryan’s beliefs and Biblical history; the questions ranged from Noah and the Flood, Jonah and the Whale, ancient civilizations, and the age of the Earth.[6] Although I understand Darrow’s purpose in asking these questions, I’m surprised the judge allowed such personal attacks against Bryan. The case is about John Scopes and the Tennessee law he infringed, not about whether Bryan believes Joshua made the sun stand still. Even more, Darrow’s clear skepticism and dislike for the antievolution crusade influences how he presents the trial to the American people, publicly disparaging Bryan. Darrow’s inquiries were such that Bryan was forced to choose between his beliefs and modern knowledge; in either case, Bryan lost face because, by choosing the former, he was showing ignorance and, by choosing the latter, he was showing that some degree of biblical interpretation was necessary.[7] So while the Scopes Trial was supposed to be about academic freedom and individual liberties, the presence of both Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan transformed it into a creationalist–evolutionist controversy that pitted fundamentalists against modernists, atheists, and agnostics.

______________________________________________________________

Lizbeth Herrera Gomez is currently a sophomore attending the University of Chicago. She is double majoring in Law, Letters, and Society and Political Science, with a minor in Gender and Sexual Studies.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Larson, Edward. “Summer for the Gods.” Basic Books, 2006, pp. 71.

[2] Larson, Edward. “Summer for the Gods.” Basic Books, 2006, pp. 103.

[3] Larson, Edward. “Summer for the Gods.” Basic Books, 2006, pp. 71.

[4] Larson, Edward. “Summer for the Gods.” Basic Books, 2006, pp. 100.

[5] Larson, Edward. “Summer for the Gods.” Basic Books, 2006, pp. 187.

[6] Larson, Edward. “Summer for the Gods.” Basic Books, 2006, pp. 187.

[7] Larson, Edward. “Summer for the Gods.” Basic Books, 2006, pp. 188.

0 notes

Text

An Analysis of Mexican Labor in California

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

March 6, 2024

Mexican labor wasn’t always the farm employers’ first choice, it was only through the advent of the Immigration Act of 1924 and the repatriation of Mexican workers in the 1930s that they moved away from Asian labor. However, tension emerges from the American desire for migrant labor and the simultaneous want to preserve a white Anglo-Saxon majority. Furthermore, the American desire for seasonal and migratory labor has only heightened the country’s contrasting economic and social interests.

The rise of industrialized farming promoted the idea of seasonal and migratory labor in California. Large-scale farmers, under the California Farm Bureau Federation (CFBF) and the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF), emphasized the need for seasonal and migratory laborers because they wanted labor that could be used “flexibly and deported easily.”[1] Flexible labor refers to the ability to control the influx of laborers according to supply and demand; for example, deporting people when there is an oversupply of laborers or economic hardship. Flexibility also gave farm employers the security that there would be a constant mobile workforce that would respond to the “seasonal fluctuations in the need for labor.”[2] So even if laborers were deported or voluntarily left to their home countries during the off-season, the farm employers knew they would return.

However, there was a question of choosing which seasonal and migratory laborers to employ for California’s labor-intensive crop production. The ideal laborers would support the “industry’s ‘unstructured’ labor market conditions,” eliminating the possibility of white labor because they were used to higher standards of living and could easily find better wages.[3] Japanese labor was quickly dismissed when they “began to acquire land and compete with the interests of white farmers,” creating hostility towards them.[4] In response to white anxieties over competition, farm employers brought in Asian Indians and Filipinos but then the former group also became landowners.[5] And once the previous choices—Asian laborers—had been exhausted, farm employers turned to Mexican labor.

The preference for Mexican labor was consolidated through the Immigrant Act of 1924 and the repatriation of Mexican workers in the 1930s. The Immigrant Act of 1924 refers to a federal law that limited the number of incoming migrants, setting a quota that, particularly, barred Japanese immigration.[6] Mexican immigration, on the other hand, had no limits causing a substantial increase in the Mexican population living in California. While many politicians voiced their concerns over Mexican immigration, CFBF and AFBF convincingly expressed that Mexicans—unlike Blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos—could be deported if they later proved to be a menace.[7] This, of course, proved to be true when the U.S. sought to repatriate Mexican people to their home country, in which “an estimated half million Mexican nationals and U.S. citizens of Mexican descent” were forced to return to Mexico.[8] As a result of Mexico’s nonquota status and the easy deportation of its people, Mexican labor became the bedrock of California’s agricultural workforce.

The notion of seasonal and migratory labor was again promoted under the context of Mexican labor because U.S. politicians wanted to meet agricultural labor demands without the responsibility of managing the migrant workers. So the ability to send “laborers back to Mexico upon completion of work or in times of economic downturn" perfectly suited the industry's desire to maximize labor utility and production, while minimizing the social burden on the state.[9] This, to me, has echoes of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which the U.S. wanted to maximize its territory but acquire the least densely populated Mexican lands.[10] The American fear was that by absorbing mixed people, the country’s homogeneity as an Anglo-Saxon majority would be threatened. In both scenarios, the U.S. uses some unique formula that attempts to maintain a strict racial hierarchy, in which Mexican people are dismissed, ignored, and abandoned.

Whilst the American desire for migrant labor is strong, there is also an innate American impulse to reject anything non-white. This impulse to maintain an Anglo-Saxon majority has driven the development of migrant quotas, repatriation, and deportation; all methods meant to ensure limited migrant entry. However, tension emerges from such laws because the American economy—as seen with California’s agricultural workforce—rests on the labor and effort of migrants. To put it more explicitly, “immigration, for all the obstacles America throws at it, remains a boon for countless U.S. employers and a reasonable bet for migrants who seek a better life.”[11] Immigration continues to be a controversial subject in American politics because while many complain about incoming migrants, they’re also the foundation for many industries, like Californian agriculture. Furthermore, I’d like to consider how the American desire for seasonal and migratory labor has affected Mexican family dynamics, especially when the familial unit is left behind.

______________________________________________________________

Lizbeth Herrera Gomez is currently a sophomore attending the University of Chicago. She is double majoring in Law, Letters, and Society and Political Science, with a minor in Gender and Sexual Studies.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 43.

[2] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 46.

[3] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 46, 50.

[4] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 48.

[5] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 48.

[6] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 53.

[7] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 57.

[8] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 58

[9] Kim Joon K. “California’s Agribusiness and the Farm Labor Question: The Transition from Asian to Mexican Labor, 1919–1939.” Aztlán, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 55.

[10] Gonzalez, Juan. “Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America.” Penguin Books, 2011, pp. 48.

[11] Valdes, Marcela. “Why Can’t We Stop Unauthorized Immigration? Because It Works.” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/01/magazine/economy-illegal-immigration.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare.

0 notes

Text

Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA): Navigating Domestic Limitations While Abroad

By Zuri Cofer, The University Chicago Class of 2025

January 1, 2024

Despite America's proud legacy of freedom and economic opportunity, an increasing number of U.S citizens are exploring employment prospects abroad. The Association of American Resident Overseas currently estimates that approximately 5.4 million Americans reside outside the U.S., yet the Department of State puts forth a more substantial estimate, suggesting a figure closer to 9 million. [1] While the appeal of international living is undeniable—encompassing the expansion of professional networks, reduced living costs, and non-fiscal incentives like learning a new language as well as cultural immersion—there exist significant drawbacks for U.S. citizens living abroad, many of which are quite costly.

In 2010, congress passed the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) as part of the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act (HIRE). The HIRE Act was intended to stimulate job growth, offering distinct tax benefits to qualifying employers for both hiring and retaining employees. [2] In a similar fashion, FATCA was designed to retain funds within the U.S., compelling foreign financial institutions and specific non-financial foreign entities to report on the foreign assets held by their U.S. account holders. Failure to comply could result in withholding on withholdable payments, and as of January 2013, the HIRE Act forces foreign financial institutions, trusts, and corporations to choose between either agreeing to provide the IRS with with information regarding their U.S. account holders, grantors, and owners or face a 30% withholding tax on nearly any payment received from a U.S. payor. [3]

Additionally, FATCA included legislation that required U.S citizens to report their foreign financial accounts and foreign assets. [4] This obligation brought many investment and tax constraints. Notably, the United States stands as one of only two countries globally that imposes taxes on the worldwide income of all citizens and permanent residents, regardless of where they live and earn an income, as well as how they choose to utilize that income. [5] In the context of long term investments, while Americans residing outside the U.S. have the option to contribute to an individual retirement account (IRA). However, they must possess earned income that is not excluded by the foreign earned income exclusion (FEIE), a provision designed to diminish or eliminate U.S. taxes on foreign income earned while working abroad, along with the foreign housing exclusion (FHE). [6,7]

Therefore, it is not uncommon to have most, if not all, of one’s foreign income excluded from U.S. taxes, leaving minimal eligible income for retirement investments. While the seemingly logical alternative would be to invest in mutual funds abroad, it is more often a con than a pro. To the IRS, a foreign mutual fund is considered a Passive Foreign Investment Company (PFIC). PFICs are subject to highly punitive tax treatment by the U.S. tax code. Not only will the tax rate on these investments be much higher than that of similar or identical U.S. registered investments, but the cost of required accounting for reporting PFIC investments on IRS Form 8621 can run into the thousands of dollars per investment each year. [8]

Given these limitations, it raises the important question of how Americans abroad will retire. While there is not a simple solution, it is important to note that the severity of these limitations varies by country, as well as the incentives for other countries to report back to the US on citizens living abroad. Regarding European and Western nations, there is significant incentive to maintain good relations with the United States, given that many banks abroad have investments in, or desire to have access to the American market. Additionally, many Western economies depend on American tourism, further emphasizing the complexities surrounding retirement planning for U.S. citizens residing outside the country. Due to this, penalties for not reporting on the incomes and assets of Americans living in their countries are more of a concern to Western nations because they do not want to lose access to the American market. However, for many non-Western countries, there often is no FATCA agreement. In fact, about 94 countries currently have no FATCA agreements with the US, most of which are located in Africa and the Caribbean. [9] Therefore, throughout the next decade, we may see a greater number of expatriates taking jobs in Africa and the Caribbean—a choice emerging from the desire to establish long-term residence outside the United States as well as the intention to optimize financial resources and gain flexibility to hold foreign investments.

——————————————————————————————————

Zuri Cofer is pursuing a B.A. in Environment, Geography, & Urbanization as well as Anthropology at the University of Chicago. She is planning to graduate in the Spring of 2025 and pursue a J.D.

——————————————————————————————————

[1] “How Many Americans Live Abroad?” AARO.

[2] “Fisher Phillips the Hire Act: Who, What & How.” Fisher Phillips.

[3] “Obama’s Hire Act -- Explaining the Tax Provisions.” Baker Donelson.

[4] “Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA).” Internal Revenue Service.

[5] Katelynn Minott, CPA & CEO. “What Is Citizenship-Based Taxation?” Bright!Tax Expat Tax Services, 27 Oct. 2023.

[6]Block, H&R. “The Foreign Earned Income Exclusion for U.S. Expats.” H&R Block®, 10 Jan. 2023.

[7] Suji. “How Do Iras and Roth IRAS Work for Expats?” Creative Planning International, 8 May 2023.

[8] “Common Investment Mistakes Made by Americans Abroad.” Creative Planning International, 8 May 2023.

[9] “Best Citizenships.” Best Citizenships, 30 Nov. 2023.

0 notes

Text

Language and Immigration: Unraveling the Impact on Latino Men

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

December 31, 2023

Interior immigration enforcement has disproportionately targeted Latino men. A move was made towards interior enforcement because of the 9/11 attacks, so migrants became seen as terrorists, criminals, fugitives, and illegal. As such, a tension emerges between the public perception of an immigrant danger and the reality of what terms–criminal, fugitive, illegal–really mean. Furthermore, the shift towards interior enforcement and the weaponization of language has created a gendered racial removal program that apprehends and deports Latino men.

Since the aftermath of 9/11, the U.S. has focused on interior immigration enforcement. Interior enforcement refers to migrants being removed from inside the country.[1] Removals are separate from returns because the latter occurs when Border Patrol agents deny migrants entry into the country. Interior enforcement can be seen most clearly in the number of ICE–U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a branch under the Department of Homeland Security–apprehensions between 2002 and 2011. In 2002, “interior apprehensions accounted for 10 percent,” but by 2011, “that figure was nearly 50 percent”.[2] The great increase in apprehensions stems from the belief that migrants, as terrorists and criminal aliens, pose a great risk to national security.[3] So when the recently created Department of Homeland Security tells the American public that mass deportations are the best way to maintain their safety and protection, they believe it.

Since moving to interior enforcement, DHS has developed a list of terms to vilify migrants: criminal alien, fugitive alien, and illegal alien. Firstly, criminal alien refers to migrants who have been convicted of crimes. And while the word “criminal” may conjure up images of violent homicides and assault, “36.9 percent of criminal deportees in FY 2008 were deported for drug offenses and 18.1 percent for immigration offenses”.[4] The majority of deportees, 55 percent, have only been convicted of drug and/or immigration offenses, which aren’t the violent crimes the American public believes they’re being protected from. Secondly, fugitive alien refers to either people who have been released from ICE and failed to report to their immigration hearings and/or people who have a deportation order but still haven’t left the country.[5] So a “fugitive alien,” isn’t necessarily someone who is fleeing from the law. Thirdly, illegal alien refers to migrants who have entered the country illegally or overstayed their legal entry.[6] Such dehumanizing labels weaponize language to deport countless migrants, all under the guise of maintaining national security.

The power of language is similarly seen in The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas. In this book, Monica Muñoz Martinez describes how postcards would depict murdered Mexican people as greasers and bandits, relying on racist and derogatory labels to promote sales.[7] Those postcards would then become a cultural staple, with Anglo-Saxons believing that such bandits, thieves, and greasers deserved to die. Instead of feeling sympathy for the corpses, people would joyously celebrate the great triumphs of the Texas Rangers. And if people believe that such disparaging terms are a thing of the past, the former president of the United States has publicly said that Mexican people are bringing drugs and crime, that “they’re rapists.” The worst part is that some have defended such offensive remarks. So language continues to be the most powerful tool to affect public opinion.

Mass deportations disproportionately affect Latino men, establishing a gendered racial removal program. For example, El Salvador found that “95 percent of deportees are men,” of which “three quarters were undocumented in the United States”.[8] And while El Salvador is given as an example, darker Latinos are “more likely than immigrants from the rest of the world to face deportation”.[9] To be clear, darker Latinos refers to migrants from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Mexican people, in particular, are racially profiled as illegal because “popular opinion in the United States associated ‘Mexicanness’ with illegality”.[10] The power of language resurfaces in this instance because while Trump isn’t the only person who has publicly disparaged Mexican people, he’s the one with the most political clout. Nevertheless, the gendered racial removal program affects all Latino men, with some being more racially profiled than others.

Overall, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 have created rippling effects on undocumented, migrant men living in the U.S. The emergence of labels–criminal, fugitive, illegal–has given the American public a misconceived notion about migrants, believing that mass deportations are the only way to ensure their safety from an “immigrant danger.” The reality is that such danger doesn't exist, but the myth is continuously fed by the weaponization of language. In the end, negative public opinion on immigration disproportionately harms Latino men and the families that depend on them.

______________________________________________________________

Lizbeth Herrera Gomez is a sophomore attending the University of Chicago. She is double majoring in Political Science and Gender and Sexual Studies

______________________________________________________________

[1] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 276.

[2] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 277.

[3] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 273.

[4] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 280.

[5] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 281.

[6] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 281.

[7] Muñoz Martinez, Monica. 2018. The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 233.

[8] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 274.

[9] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 282.

[10] Golash-Boza, Tanya and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2013. "Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program." Latino Studies 11(3): 282.

0 notes

Text

Tort Reform: A Conversation on Economics, History, & Social Stratification

By Zuri Cofer, The University Chicago Class of 2025

December 3, 2023

Torts law, one of the fundamentals taught in law school, often has law students spending hours in the library, analyzing the various technicalities involved in calculating damages and determining legal liability. But what truly are the parameters of torts law, and why, considering it's not popularized to the general public, should people care about tort reform?

Tort law, in its current form, aims to compensate individuals for injuries resulting from wrongful conduct. It is designed to discourage people from engaging in behavior that could potentially harm others by placing strict penalties for causing wrongful injury [1]. Originally arising in the United States during the Industrial Revolution, tort law became a necessity due to an influx in “manufactured injury” associated with the proliferation of complex machinery capable of crushing human bodies [2]. Larger businesses were making copious amounts of money from these technological advances, and since workers were easily replaceable, there was a tempting and seemingly logical fund that could presumably be used to compensate the injured and the families of the deceased. However, there was no legislation forcing this compensation. While the profit-oriented option, as unethical as it may seem, appears to not compensate workers and/or their families, businesses slowly moved in favor of compensation. “No ties of blood or love prevented one cog in the machine from suing the machine and its owners;” therefore, long term lawsuits about damages could stunt profits, and a decision had to be made about economic growth and the well-being of industry [2]. As the field grew into its form of today, it established itself within the concept of negligence, imposing consequences for harm caused by carelessness, based on the principles of fault and responsibility [2].

However, while necessary, torts law comes with its drawbacks, as it can foster a culture in which plaintiffs are too eager to sue, and juries are too willing to award substantial amounts in damages [3]. It has also been attributed to an increase in insurance and medical costs, as insurance companies often must pay large damages on behalf of their clients charged with negligence in personal injury lawsuits [4]. But this is not always necessarily true and does not need to be the case if we consider tort reform. Tort reform is a “legislative adjustment to the way that the legal system in some states address personal injury lawsuits,” generally limiting the financial award that a jury can provide in compensation for damages [4]. While this would help alleviate the financial requirements that insurance companies feel juries over-administer for tort victims, it does not necessarily mean that insurance companies will automatically lower their rates, as there still exists other compounding factors, such as what insurance package an individual is on or how they have assorted their coverage. Additionally, in states where tort reforms have been focused on bad faith, noneconomic damage caps, and/or modifications to joint and several liability, there has been no measurable impact [4]. In the case of auto insurance, such reforms have not diminished the number of people driving without auto insurance, thereby undermining the idea that tort reform would decrease the number of uninsured drivers. [4]

There are also discrepancies in how damages and compensation are received by the victims. When calculating compensation, courts will consider various factors such as medical expenses, lost income, expenses related to property damage, and emotional suffering. Additionally, race, occupation, and gender are taken into account, leading to the allocation of significantly lower damages for minority men and women [5]. It should also be noted that such disparities exist within racial groups, where women of the same race are valued less than their male counterparts. This disparity can be attributed to the “methods used to calculate future losses of injured parties, including lost future earning capacity and future medical expenses” [6]. The assumption is that due to historical inequalities creating structural socioeconomic inferiority for minority groups, resulting in a higher proportion of them in a lower income threshold compared to white individuals, their earning potential in relation to white individuals is considered lower. This provides the basis for justifying the allocation of less compensation, and essentially enshrines discriminatory practices of the past into law and assumes their continuation into the future [6]. It also gives fewer incentives for landlords, government housing authorities, and industrial companies to consider environmental impacts when building structures for or around people of color [6].

Therefore, whether you identify with a marginalized group or less-valued gender, tort reform should be of interest due to its direct impact on your everyday life. It plays a crucial role in determining your worth under the law as well as how your insurance companies value you and your money. However, torts law goes beyond individual concerns; it unveils deeply rooted historical injustices in the United States, providing a lens through which we can examine how contemporary forms of the law perpetuate societal inequalities. This raises valuable questions about the extent of the equitable nature of tort law, given its default favoring of certain individuals over others. This inquiry sparks discourse on the morality within the legal system and underscores how reform policies may change based on the interests of the government. Notably, there's a considerable variation in these interests between state governments and between them and the federal government. This ethical battle involves the consideration of economic contributions, social stratification, and political power, which will be essential in the upcoming conversations on tort reform.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Introduction to Tort Law - CRS Reports, crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11291.

[2] Friedman, Lawrence M., 'Torts', A History of American Law, 4th edn (New York, 2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 24 Oct. 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190070885.003.0015,

[3] Christy Bieber, J.D. “What Is Tort Reform? (2023 Guide).” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 17 July 2023, www.forbes.com/advisor/legal/personal-injury/tort-reform/#:~:text=Tort%20reform%20very%20broadly%20refers,they%20do%20file%20a%20lawsuit.

[4] “How Has Tort Reform Affected Auto Insurance Rates? Vanasse Law.” Lancaster Workers Compensation Attorney, 23 Nov. 2020, https://vanasselaw.com/tort-reform-affected-auto-insurance-rates/

[5] “How Are Damages Established in a Tort Claim?” CEO Lawyer, 8 Dec. 2022, https://ceolawyer.com/faq/georgia-law/personal-injury-law/how-are-damages-established-in-a-tort-claim/

[6] Chamallas, Martha, 'Race and Tort Law', in Devon Carbado, Emily Houh, and Khiara M. Bridges (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Race and Law in the United States (online edn, Oxford Academic, 13 Jan. 2022), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190947385.013.5.

0 notes

Text

Gender Injustice in Familial Structures: Susan Moller Okin’s Critique of Rawls’ Two Principles of Justice

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

November 26, 2023

Rawls’ two principles of justice affects the family structure because it excludes sex from the veil of ignorance, causing injustice to enter the family unit, particular between man and woman. Furthermore, the two principles of justice, that apply to political society, shouldn’t regulate the family because it creates an unjust gendered division of labor.

In A Theory of Justice[1], John Rawls presents the two principles of justice. The first principle of justice—everyone must have an equal right to equal basic liberties—secures the most fundamental of rights and the second principle demands that social and economic inequalities be arranged to everyone’s advantage and attached to the positions and offices open to all.[2] The second principle, often referred to as the difference principle, protects the least advantaged populations by ensuring that inequalities stand only if they’re to the advantage of the worst off.[3] In other words, inequalities in life prospects are permissible if the worst off, or interchangeably the least advantaged populations, benefit.

The two principles of justice matter because within the original position—a hypothetical situation in which people are under a veil of ignorance—people would select this concept to apply to political society; society is a cooperative venture for mutual advantage.[4] Under the veil of ignorance, people don’t know how the choices made in the original position would affect their particular situations in society, so they would choose the two principles because it best guards their liberties and the worst off. People, specifically, don’t know their social status, class position, fortune, intelligence, strength, psychological propensities, or their conception of the good.[5] There is, notably, no mention of sex or gender, so one can assume that people know that fact under the veil. And for the purposes of this article, I’ll be using sex and gender interchangeably, referring to the gender binary of men and women. Moreover, Rawls’ two principles of justice are used in political society.

I mention the absence of sex in the veil because it deeply affects the relationship dynamics within a family. The “monogamous family” is an example of a major social institution–the political constitution and principal economic and social arrangements–that distributes fundamental rights and duties.[6] The familial unit determines people’s rights and duties, which affect their life prospects. Not to mention that Rawls doesn't specifically claim to whom the two principles of justice should apply, he continuously uses “men” to refer to people. Nevertheless, how the basic structure of society–the way in which the “major social institutions distribute fundamental rights and duties and determine the division of advantages from social cooperation”[7]–develops specifically affects men–the gender–because they decide how to regulate claims against each other and what counts as just and unjust.[8] While Rawls doesn’t genderize, in this passage he did use masculine pronouns–him, his–so one can assume that men are the ones who decide how to best distribute rights, duties, and advantages, leaving women and children with no voice in the matter.

In ‘Forty Acres and a Mule’ for Women[9], Susan Moller Okin takes issue with Rawls’ two principles of justice because they don’t address family justice. By family justice, Okin refers to the “traditional division of labor by sex and its many social, economic, and political ramifications.”[10] Given that families are considered a major social institution, there should be a greater emphasis placed on internal social dynamics because the distribution of rights and duties commonly disfavors women. While men are viewed as “autonomous, independent, and often self-interested individuals,” women are viewed as dependent with no autonomy.[11] Men’s autonomy causes them to take on a greater role in public life, whilst the women stay home and take care of the children. In that case, women are forced to carry the burden of child-rearing while the men voice their needs and socialize in public life, which is only possible because the women take care of their needs. Thus, there is no family justice in the gendered division of labor.

Instead of addressing how the two principles of justice influence the inner workings of the family, Rawls assumes the family structure is just. Rawls claims it’s a “given that family institutions are just,” without justifying why that is.[12] When, in fact, it’s not a given that family arrangements are just because the two principles of justice could develop in a way that excludes women; consequently, making the family unjust. The two principles had originally included the family “as part of the basic structure of society,” but it then went on to “treat women, the family, and love as outside of the realm of justice.”[13] So while the two principles were properly applied to the family structure, they excluded women. Once justice doesn’t apply to the mother, the family is subject to injustice because the gendered division of labor undermines the “sense of justice in the children.”[14] Since Rawls doesn’t specify how the family should be structured, the gendered division of labor unjustly weighs on women; when the children see the relationship dynamic between their parents, they believe that to be the correct distribution of rights and duties and perpetuate that injustice. So the assumption that families are just, isn’t enough to bar the unjust division of labor based on sex.

Although Rawls’ difference principle is meant to guard women, it isn’t enough. To be clear, inequality is only justified if it’s “to the advantage of women and acceptable from their standpoint.”[15] In principle, men can only be favored in the assignment of basic rights if it’s to the advantage of women, but, as was stated above, the practice of the two principles of justice could develop and exclude women from consideration. Nevertheless, Rawls does continue to say that inequalities are “seldom, if ever, to the advantage of the less favored,” so men shouldn’t be favored in the distribution of fundamental rights and duties.[16] Distinctions based on sex are treated as starting places in the basic structure because it’s a characteristic that can’t be changed and isn’t obscured by the veil. So when men take on a favorable assignment of basic rights, they do it knowing they’re different from women. And in many cases, the sex distinction is used to justify the gendered division of labor as natural.[17] Furthermore, the principles of justice used in political society wouldn't apply to family structures.

______________________________________________________________

Lizbeth Herrera Gomez is currently a sophomore attending the University of Chicago. She is double majoring in Political Science and Gender and Sexual Studies.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Belknap Press, 1971.

[2] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page53.

[3] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page68.

[4] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page4.

[5] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page11.

[6] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page6.

[7] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page6.

[8] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page10-11.

[9] Okin, Susan Moller. “‘Forty acres and a mule’ for women: Rawls and feminism.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 4, iss. 2, 2005, pp. 233-248. Sage Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X05052540.

[10] Okin, Susan Moller. “‘Forty acres and a mule’ for women: Rawls and feminism.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 4, iss. 2, 2005, pp. 235.

[11] Okin, Susan Moller. “‘Forty acres and a mule’ for women: Rawls and feminism.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 4, iss. 2, 2005, pp. 239.

[12] Okin, Susan Moller. “‘Forty acres and a mule’ for women: Rawls and feminism.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 4, iss. 2, 2005, pp. 236.

[13] Okin, Susan Moller. “‘Forty acres and a mule’ for women: Rawls and feminism.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 4, iss. 2, 2005, pp. 237.

[14] Okin, Susan Moller. “‘Forty acres and a mule’ for women: Rawls and feminism.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 4, iss. 2, 2005, pp. 237.

[15] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page85.

[16] Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice, page85.

[17] Okin, Susan Moller. “‘Forty acres and a mule’ for women: Rawls and feminism.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 4, iss. 2, 2005, pp. 239.

0 notes

Text

Examining the Relationship Between Politics & Climatology: The History of ExxonMobil’s Climate Research

By Zuri Cofer, The University Chicago Class of 2025

November 15, 2023

This past October, ExxonMobil, one of the largest publicly traded petroleum and petrochemical enterprises in the world, reached a deal to buy Pioneer Natural Resources for $60 billion. [1][2] If the deal goes through, the combined company would have the power to pump 1.2 million barrels of oil a day, more than double its closest competitor. [2] This sparked controversy amongst congress and prompted nearly thirty government officials to write a letter to the Federal Trade Commission arguing that the acquisition would harm competition and risk raising consumer prices.[2] There also exists the issue of the environment, as increased oil drilling has been associated with environmental harm. Despite such objections, Exxon claimed that “it and Pioneer represent just about 5% of US oil production combined,” before further arguing that “the deal would be positive for the environment.”[2] This is not the first time the company has claimed its operations to be both economically and environmentally beneficial as it has a history of aligning its actions with economic growth and environmental prosperity. In the 1980s, ExxonMobil began making positive associations between fossil fuels and the environment to justify their profit-based interests to the public. [3][5] Decades later, it was found that the oil giant’s own research during the 1970s and 80s confirmed that fossil fuels played a role in global warming, indicating that the company knew that their operations could potentially have negative impacts on the environment.[1]

In 1978, former senior company scientist, James F. Black wrote to the former Vice President of Exxon Research and Engineering, F.G Turpin. Within this letter was a transcript of Black’s 1978 lecture presented to Exxon’s Management Committee on the relationship between the greenhouse effect and global warming. [3] According to Black, the greenhouse effect refers to the “warming of the Earth’s atmosphere due to an increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide.”[5] He states that atmospheric scientists generally attribute this phenomenon to fossil fuel combustion as it is “the only readily identifiable source” that is both large enough to account for the observed increases as well as “capable of affecting the Northern Hemisphere first.”[5] Despite this, most scientists agreed that more research would be needed to definitely establish the extent of this relationship. Black notes that there are considerable uncertainties and limitations within climate science, particularly in making mathematical models to represent the various “complicated interactions” between factors such as cloud density and ocean circulation.[5] It should be noted, however, that the relationship between fossil fuel combustion and global warming was considered to be direct; as combustion increases, so does atmospheric carbon dioxide, thereby intensifying the greenhouse effect. It was the extent of this relationship that was uncertain, rather than the relationship itself. Given this uncertainty, Black recommended that Exxon dedicate more research to the subject. Concluding that, although it is premature to limit the use of fossil fuels given uncertainties in climatology, fossil fuels should not be encouraged as the human race can only afford about a five-to-ten-year window to establish a plan to combat global warming.[5]

[6] Black, James F. James F. Black to F.C Turpin, June 6, 1978. Letter. From Climate Files.

Black’s lecture arguably acted as a foundation to the various research operations Exxon conducted on the environmental consequences of fossil fuel combustion during the 1970s. Following Black’s recommendation, Exxon launched an extensive research program, spending over a decade deepening their understanding of how carbon dioxide emissions “posed an existential threat to the oil business.”[3] By 1982 Exxon “confirmed an emerging scientific consensus that warming could be even worse than Black had warned five years earlier.”[3] In spite of this revelation, the company began to cut back on their research and placed firm restrictions on how research conclusions were distributed. Stated in a memo from the Manager of Environmental Affairs, M.B Glaser, Exxon workers were prohibited from distributing research findings externally as the company had realized that combating the greenhouse effect would require “major reductions in fossil fuel combustion.”[3][4] Because Exxon’s operations were founded upon the use of fossil fuels, combating warming from the greenhouse effect was thought to diminish profits and signal the end of the company’s economic success. To counter this, Exxon began to argue that global warming was not a present issue and looked for ways to justify the use of fossil fuel.

It is evident that Exxon’s “early determination to understand rising carbon dioxide emissions grew out of a corporate culture of farsightedness,” as maximizing profits was their primary concern.3 Additionally, the 1970s and 80s were important years in climatology as many discoveries on the relationship between global warming and fossil fuel became popularized by mainstream media. This increased pressure on the fossil fuel industry to advertise their operations as either having no environmental effect or having a positive effect. They relied on politicians to keep emission regulations at a minimum, and in order to keep those politicians in power, the industry needed to convey a positive association between fossil fuel and environmental politics, thus exemplifying the role of public opinion in climate discourse.[5]

The contrast in desire to research the greenhouse effect from Black’s lecture to Glaser’s 1982 memo exemplifies the evolving relationship between politics, economic interest, and environmentalism in the 1970s and 80s. And it prompts the question of how independent climate policy is from partisan politics.

______________________________________________________________

[1] “Our History.” ExxonMobil, Exxon Mobil Corporation,

https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/who-we-are/our-global-organization/our-history#:~:text=Over%20the%20past%20140%20years,petrochemical%20enterprises%20in%20the%20world.&text=Today%20we%20operate%20in%20most,%3A%20Exxon%2C%20Esso%20and%20Mobil. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

[2] Goldman, David. “Chuck Schumer and Elizabeth Warren Want FTC to Probe Blockbuster

Exxon, Chevron Mergers | CNN Business.” CNN, Cable News Network, 1 Nov. 2023, www.cnn.com/2023/11/01/investing/oil-merger-exxon-chevron-schumer/index.html. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

[3] Climate-Admin. “Exxon’s Own Research Confirmed Fossil Fuels’ Role in Global Warming

Decades Ago.” Inside Climate News, 27 Apr. 2021, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/16092015/exxons-own-research-confirmed-fossil-fuels-role-in-global-warming/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

[4] Glaser, M.B. M.B Glaser to ExxonMobil 1982. Memo. "Greenhouse" Effect

https://insideclimatenews.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/1982-Exxon-Primer-on-CO2-Greenhouse-Effect.pdf (accessed November 5, 2023).

[5] Weart, Spencer. The Discovery of Global Warming: Revised and Expanded Edition (2008).

[6] Black, James F. James F. Black to F.C Turpin, June 6, 1978. Letter. From Climate Files.

https://www.climatefiles.com/exxonmobil/1978-exxon-memo-on-greenhouse-effect-for-exxon-corporation-management-committee/ (accessed November 3, 2023).

0 notes

Text

Appropriation & Acquisition: How Section 7008 of the U.S Annual Appropriations Act Impacts U.S Interests in Niger

By Zuri Cofer, The University Chicago Class of 2025

October 16, 2023

This past week, the Biden administration formally labeled the July 2023 militant removal of Nigerien President, Mohamed Bazoum, as a coup. This decision ultimately strained the United States’ relationship with Niger as the formal recognition of the coup triggered the use of Section 7008 of the Department of State’s annual appropriations act. This act describes how government aid is to be suspended if a “country’s military has overthrown, or played a decisive role in overthrowing, the government” [1].

Aid Termination Before & After 7008

On October 10th, the U.S Department of State issued a statement noting that in accordance with section 7008 of the annual appropriations act, the United States would be suspending most of its assistance to the government of Niger [2]. This suspension includes the termination of certain foreign assistance programs that were previously temporarily paused in August, programs which total nearly two hundred million dollars. However, aid suspensions began long before this week’s developments. The Millennium Challenge Corporation, for example, a bilateral United States foreign aid agency [3], suspended its aid to Niger in August, including its $302 million Regional Transportation Compact.

PUBLIC LAW 117–328—DEC. 29, 2022 136 STAT. 4459

Prior to these suspensions, both those before and after the U.S acknowledged the coup, the Department of Defense had already ended security cooperation and counterterrorism operations with the Nigerien government and proceeded to strengthen its branches in both Niamey and Agadez [4].

Western Interest in Niger

Valued globally for its rich resources, extensive economic potential, and proximity to Europe and the Middle East, Niger has increasingly become a country of Western interest. Prior to the coup, Niger served as a key ally in American, French, and Italian operations to fight against extremists in the Sahel region. Niger, along with Tunisia, Libya, and Morocco, have all been partners in stopping migrants from crossing the Mediterranean into Europe. But as chaos ensued and aid suspended, the U.S government was posed with the challenge of ensuring Niger continues to be a partner in counterterrorism efforts. There is also the concern that the country will turn to the Russian mercenary group, Wagner, for security assistance, as others in the region have [5]. Given the restrictions from section 7008, the “U.S military operations in Niger are now limited to flying intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance aircrafts to ensure the continued safety of the U.S personnel who remain in the country” [6]. Additionally, major counterterrorism operations will remain paused given that their continuance to work with the Nigerien armed forces would be a violation of section 7008 [6].

Wagner Group

Days after the July coup, Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin, offered his services to the new junta leader, raising suspicions that Moscow had orchestrated the uprising; however, there is no current evidence to show that either Prigozhin or President Vladimir Putin were involved in the takeover [7]. Despite this, the removal of Bazoum posed an important opportunity for both Prigozhin and Putin to move on from the failed mutiny attempt in June and demonstrate how the Wagner Group presence is strengthening in Africa while the presence of Western militaries, particularly of France and the United States, fades [7].

The United States previously had about 1100 troops between its two military bases in Niger. It cooperated with government officials and operated a security cooperation assistance program for Nigerien troops fighting Al Qaeda and other extremist militants in the Sahel [7].

As of last August, the Wagner Group had deployed forces in Mali, Libya, the Central African Republic, and Sudan, siphoning resources, and offering a quid pro quo of military personnel in exchange for mining contracts to extract gold, diamonds, and other commodities [7]. However, despite its first look success, the Wagner Group has made enemies of terrorist organizations in the area, prompting a spike in extremist recruitment, and thus posing as a security risk to the United States. The coup has the potential to bring in extremist members from Nigeria, shutting the U.S out of the region and placing Wagner as a greater threat to U.S operations [7].

Now formally acknowledged by the U.S government, the Nigerien coup has proven to be far more complex, extending beyond a domestic issue of power. Section 7008 demonstrates the tension between amended U.S law and global interest as the U.S struggles to compete with the Wagner group in a proxy-like war.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Coup-Related Restrictions in U.S. Foreign Aid Appropriations, sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF11267.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct. 2023.

[2] “Military Coup d’etat in Niger - United States Department of State.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, 10 Oct. 2023, www.state.gov/military-coup-detat-in-niger/.

[3] Millennium Challenge Corporation, www.mcc.gov/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2023.

[4] “U.S. Says July Ouster of Niger’s Government Was a Coup.” U.S. Department of Defense, www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3552918/us-says-july-ouster-of-nigers-government-was-a-coup/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2023.

[5] Kelemen, Michele. “Here’s Why Niger’s Coup Matters to the U.S.” NPR, NPR, 27 July 2023, www.npr.org/2023/07/27/1190463279/niger-coup-us-counterterrorism-boko-haram-isis.

[6] “U.S. Says July Ouster of Niger’s Government Was a Coup.” U.S. Department of Defense, www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3552918/us-says-july-ouster-of-nigers-government-was-a-coup/. Accessed 13 Oct. 2023.

[7] Clarke, Colin P. “If Your Country Is Falling Apart, the Wagner Group Will Be There.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 11 Aug. 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/08/11/opinion/wagner-russia-prigozhin-bazoum-niger.html

0 notes

Text

The United States And Environmental Law

By Zuri Cofer, The University Chicago Class of 2025

October 7, 2023

Since 2016, forty-three million children have been displaced by extreme floods, storms, droughts, and wildfires [1]. Many of these children are from developing countries that lack the proper infrastructure to combat the globe’s rising temperatures and changing climates—countries that have had little impact at the climate crisis at large, compared to the United States who has contributed more than 509 GtCO2 since 1850 and is responsible for the largest share of historical emissions, about 20% of the global total, as of 2019 [2].

However, in the context of American environmental discourse, this statistic is not new. The United States has historically passed and defended legislation that values the interests of partisan politics, oftentimes at the expense of climate regulation, environmental prosperity, and those affected by environmental decline. For example, between 2017 and 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency was run under Scott Pruitt, a fossil fuel-backed politician who had sued the agency 14 times [3]. Pruitt’s EPA oversaw an 85% reduction in the money corporations spend on pollution-controlling equipment and remediation as well as advocated for the repeal of the Clean Power Plan which would have presumed to yield 3,600 additional premature deaths, 90,000 asthma attacks in children, and 300,000 missed workdays and schooldays each year [4].

Another example of the intertwined relationship between partisan interest and environmental policy is the decade of sharply rising oil prices beginning around 2000. The issue of America’s oil supply was taken up by the right, which sought the relaxation of environmental controls to allow increased domestic production—a campaign supported by the populist, anti-Arab claim, unsupported by any evidence, that this would reduce America’s dependence on “Arab oil,” despite Arab countries supplying the United States with less than nine percent of its oil consumption [5]. This stance not only was damaging from an environmental standpoint as increased domestic production meant more drilling, but also from a social one as anti-Arab sentiment was already prevalent in the United States following 9/11.

Political and economic interests are core values of the United States government, therefore maintaining a position of environmentalism from a governmental standpoint is difficult, given that environment conscious policy is often perceived as less economically prosperous, and at times, socially progressive.

In fact, of the twelve 2024 presidential candidates, interests vary as few candidates have concrete plans to solve the climate crisis, and some others have gone as far to denounce the concept entirely. There also are contradictions, for example, President Biden has invested billions into green infrastructure and renewable energy since obtaining his position in 2020, but has also approved the Willow Project, a massive decades long oil drilling venture in Alaska, in order to avoid steep fines and a lawsuit from Conoco had he halted the project entirely [6][7].

Despite the Biden Administration being relatively environmentally conscious, the Willow Project demonstrates that money is still at the center of environment policy and political intent. The area where the project is planned to take place is projected to hold up to 600 million barrels of oil and despite the massive impact this project could have on the environment, the cost of a lawsuit did not outweigh the cost on the environment. The Biden Administration's decision is arguably understandable; however it displays how the environment ranks below economic gain, or rather, the absence of economic loss.

In an era of global warming and partisan politics, environmental policy in the United States has depended on the interests of the sitting government as well as the government’s relationship with corporations and large companies. When considering environmental legislation, one must also consider capital gain as it is a core factor in political and economic success.

______________________________________________________________

[1] https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/2024-presidential-candidates-stand-climate-change/story?id=103313379

[2] https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-which-countries-are-historically-responsible-for-climate-change/

[3] Malin, Stephanie. 2018. “Developing Deeply Intersectional

Environmental Justice Scholarship” in Environmental Sociology

[4] https://www.americanprogress.org/article/scott-pruitts-culture-corruption-will-cost-americans-hundreds-billions-dollars-per-year/

[5] Mitchell, Timothy. 2011. “Conclusion: No More Counting on Oil” in

Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil.

[6] https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/2024-presidential-candidates-stand-climate-change/story?id=103313379

[7] https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/14/politics/willow-project-oil-alaska-explained-climate/index.html

0 notes

Text

Rousseau: The Evolution of Society through the Social Pact

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

September 3, 2023

Rousseau’s Social Contract introduces the complex role of the general will within civil society. The general will refers to the common good, or general interest, that ties people together. The general will furthers the perfect union of a state because it unifies all the wills for the common good and strengthens the social pact, from which it was created. Furthermore, the general will is necessary for human beings to live in a successful civil state because it advances the goal of the social pact: people’s preservation.

The social pact is a voluntary civil association in which people give up their freedom and independence for the benefits of society. People construct the social pact because they realize that the state of nature[1] interferes with their self-preservation.[2] In other words, people united their collective powers because, in nature, they faced obstacles they couldn’t overcome individually. This unity took on the form of a civil state that protects “the person and the goods of each associate with the full common force,” while keeping people as free as before.[3] Since society protects each person’s preservation, the social pact fulfills its role and enables people to live in a better condition than the one in nature. People in society are kept as free as they were in nature because when they lose their animalistic freedom, they earn civil freedom. This freedom doesn’t enslave people to their primitive instincts but rather allows them to engage in the intellectual and social pursuits that exist in society. In the state of nature, people don’t have intellectual pursuits because they’re only concerned with their survival. Essentially, people voluntarily enter the social pact because it maintains their preservation.

When people enter the social pact, their very humanity transforms. In society, people substitute “justice for instinct” and endow their “actions with the morality they previously lacked”.[4] Morals, like justice, are characteristics that only emerge from society because they’re social constructs that arose with people’s interdependence. The notions of justice and morality couldn’t be possible in nature because people relied on their primitive urges to survive, fully disregarding other people. But when people consult their reason, before listening to their human inclinations, they lose their animalistic independence.[5] This loss allows people to uphold the social pact because they must rely on others to secure their preservation. And the transformation from physical impulses to reason allows people to act for the betterment of society. So from the animalistic man, who was a slave to his urges, rises the civil man.

The social pact doesn’t only allow for the development of the civil man but ensures the general will is beneficial for society. The general will isn’t “so much the number of voices as the general interest that unites them”.[6] The general will aims for the general interest, or the common good of all, because it ensures the social pact remains beneficial for everyone. To clarify, the common good refers to the collective preservation of all people. Under this civil association, the common good is sustained because people gain the benefits of society: collective force and civil freedom. And for the social pact to continue being beneficial for all, everyone must put their full power “under the supreme direction of the general will”.[7] People must give up their power to the general will because when they voluntarily entered the social pact, they unanimously consented to unite and follow it. By doing this, people receive equal access to the benefits of society and can do more than simply survive. Overall, people follow the general will so that they can enjoy the benefits of society.

The Social Contract provides a crucial insight into the role of the general will for the establishment and continuation of civil society. The social pact wasn’t only created for people to officially abandon the state of nature, but for them to simultaneously receive the benefits of enhanced freedom and the collective force of society. When people receive these benefits for better living, their very makeup transforms causing them to become an integral part of society. So the general will advances the social pact and fulfills the true purpose of society—the preservation of all men.

______________________________________________________________

Lizbeth Herrera Gomez is currently a rising sophomore attending the University of Chicago. She is double majoring in Political Science and Gender and Sexual Studies.

______________________________________________________________

[1] According to Rousseau, the state of nature is a peaceful condition that exists before the socialization of people, whereby individuals act on their basic urges.

[2] Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Rousseau: The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Translated by Victor Gourevitch, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 51.

[3] Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Rousseau: The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Translated by Victor Gourevitch, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 51-52.

[4] Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Rousseau: The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Translated by Victor Gourevitch, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 55.

[5] Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Rousseau: The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Translated by Victor Gourevitch, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 55.

[6] Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Rousseau: The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Translated by Victor Gourevitch, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 64.

[7] Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Rousseau: The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Translated by Victor Gourevitch, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 52.

0 notes

Text

Firing of Pregnant Art Teacher: Crisitello v. St. Theresa School

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

August 24, 2023

When St. Theresa School, a Catholic school in New Jersey, fired Victoria Crisitello from her art teacher position, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in favor of the school. In Crisitello v. St. Theresa School, the defendant cites that because Crisitello violated the terms of her employment agreement, she could no longer remain on St. Theresa’s staff.[1] The employment agreement refers to the official “Archdiocese of Newark Policies on Professional and Ministerial Conduct,” in which employees must conduct themselves according to the teachings of the Catholic Church.[2] And since Crisitello’s pregnancy proved to have resulted from premarital sex, St. Theresa School deemed it appropriate to fire the unmarried art teacher.[3]

Crisitello then proceeded to sue under the Law Against Discrimination (“LAD”) because she felt her dismissal was due to discrimination, one based on her pregnancy and marital status.[4] But when the lawsuit was presented to the trial court, it granted a judgement in favor of St. Theresa School; when St. Theresa’s hired Crisitello, she signed an acknowledgment and understanding of employment documents, including the expected employee behavior that reflected the principles of the Catholic faith.[5] So the trial court viewed Crisitello’s termination as a result of her “violating the tenets of the Catholic Church” rather than her pregnancy or marital status, for dismissal could’ve occurred for a variety of other unseemly behaviors.[6] Nevertheless, the lawsuit continued to pass back between state trial and appellate courts for years before it reached the New Jersey Supreme Court.[7]

The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that St. Theresa’s decision to fire Victoria Crisitello was protected under the “religious tenets” exception of N.J.S.A 10:5-12(a): “It shall not be an unlawful employment practice” for a religious entity to follow the tenets of its faith “in establishing and utilizing criteria for employment.”[8] Therefore giving St. Theresa School an available defense against the claim of employment discrimination.[9]

______________________________________________________________

[1] Office of the Clerk’s Syllabus, “A-63-20 Victoria Crisitello v. St. Theresa School.”

[2] Office of the Clerk’s Syllabus, “A-63-20 Victoria Crisitello v. St. Theresa School.”

[3] The New York Times, “Court Sides With Catholic School That Fired Unmarried Pregnant Teacher.”

[4] Office of the Clerk’s Syllabus, “A-63-20 Victoria Crisitello v. St. Theresa School.”

[5] Office of the Clerk’s Syllabus, “A-63-20 Victoria Crisitello v. St. Theresa School.”

[6] Office of the Clerk’s Syllabus, “A-63-20 Victoria Crisitello v. St. Theresa School.”

[7] The New York Times, “Court Sides With Catholic School That Fired Unmarried Pregnant Teacher.”

[8] Office of the Clerk’s Syllabus, “A-63-20 Victoria Crisitello v. St. Theresa School.”

[9] Office of the Clerk’s Syllabus, “A-63-20 Victoria Crisitello v. St. Theresa School.”

0 notes

Text

Groff v. Dejoy: Balancing Faith and Employment

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

July 25, 2023

In Groff v. Dejoy, the Supreme Court dealt with whether inconveniencing coworkers constitutes an “undue burden” under Title Vll of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And if that inconvenience is such that it excuses an employer from providing an accommodation requested for religious exercise.

Groff, an evangelical Christian, refused to work on Sundays due to his religious beliefs: Sundays should be devoted to worship and rest.[1] So Groff’s place of employment, the U.S. Postal Service, redistributed Groff’s Sunday deliveries to other employees. But after being disciplined for failing to work on Sundays, Groff eventually resigned.[2] Groff felt like he had to choose between his faith and his livelihood, clearly choosing his faith.[3]

Groff sued USPS under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, claiming USPS failed to reasonably accommodate his religion.[4] Title VII is a federal law that required employers to reasonably accommodate their workers’ religious practice so long as it doesn’t pose undue hardship. Groff believed that USPS could’ve done more to accommodate his religious beliefs because the shift swaps didn’t eliminate the conflict.

And using the precedent set in Trans World Airlines v. Harrison–the Court ruled that employers need not accommodate workers if the effort imposed more than a trifling burden on their businesses[5]–USPS argued that Groff’s refusal to work on Sundays imposed a significant burden.[6]

As a result, the Supreme Court ruled that Title VII requires an employer that denies a religious accommodation to show that the burden of granting an accommodation would result in substantial increased costs in relation to the conduct of its particular business.[7]

______________________________________________________________

[1] Groff v. Dejoy. 2023. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/22-174_k536.pdf

[2] Groff v. Dejoy. 2023. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/22-174_k536.pdf

[3] “Supreme Court Sides with Postal Carrier who Refused to Work on Sabbath.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/us/politics/supreme-court-religion-sabbath-postal-worker.html.

[4] "Groff v. DeJoy." Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/2022/22-174.

[5] “Supreme Court Sides with Postal Carrier who Refused to Work on Sabbath.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/us/politics/supreme-court-religion-sabbath-postal-worker.html.

[6] “Supreme Court Sides with Postal Carrier who Refused to Work on Sabbath.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/us/politics/supreme-court-religion-sabbath-postal-worker.html.

[7] Groff v. Dejoy. 2023. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/22-174_k536.pdf

0 notes

Text

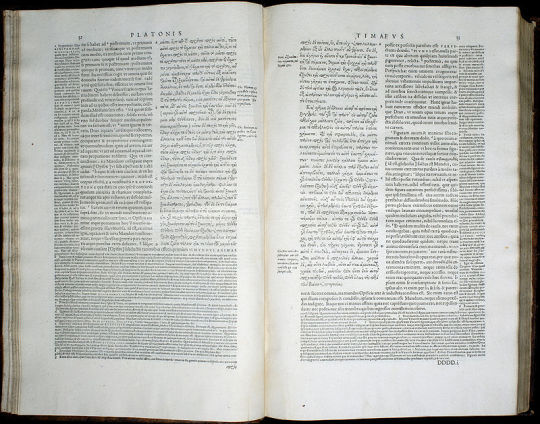

Law in Plato's Republic

By Lizbeth Herrera Gomez, University of Chicago, Class of 2026

July 23, 2023

Democracy is both undermined and safeguarded by the law because it protects the democratic man’s private freedom. This private freedom undermines democracy because it allows its citizens to do whatever they want, even if it’s hostile to the law. At the same time, the law safeguards this regime because it uses moderation to check that private freedom.

Democracy is founded on the premise of political equality because when the poor killed and cast out the previous oligarchic rulers, they established that those left must “share the regime and the ruling offices” on an equal basis.[1] Sharing the regime refers to people having equal opportunity to participate in the government and such equality is sustained through offices given by lot. And since people reflect the character of their regime, they must also be free because the city is full of freedom.[2] Essentially, the free man is the democratic man because freedom is the character of democracy. This freedom is presented as each man having the license to organize his private life however it pleases him, giving rise to private freedom that orients around a person.[3] This private freedom is directly connected to the city giving license to do whatever one wants. So although democracy was founded on the basis of political equality, it values freedom, especially when it’s attached to the person and becomes private. The democratic man has both political equality and private freedom because political equality is the founding tenant of democracy and freedom is the character of democracy.[4]

The political equality and private freedom given to its citizens is a liberality that democracy can’t afford. This liberality might make this regime appear to be the fairest, with different human dispositions decorating the regime like hues on a “many-colored cloak” but it only serves to entrap all types of regimes, making it convenient to establish a new one.[5] Democracy contains all species of regimes because private freedom allows all dispositions to exist, including those of the timocratic, oligarchic, democratic, and tyrannic man. This allows a possible descent into tyranny because the disposition already exists in a democracy. And if the rulers and the “many-colored” didn’t dispense political “equality to equals and unequals alike,” democracy would otherwise be a sweet regime.[6] In the context given, Socrates refers to the many-colored as the many-colored dispositions because a prior comparison was made between the democratic regime having multiple dispositions to a many-colored cloak.[7] The phrase, equals and unequals alike, means that citizens are all equally free in their private life - sharing the same degree of political equality and private freedom - regardless of whether they actually participate in government.

Participation in government is irrelevant for the sharing of political equality because there’s an absence of compulsion to enter the political and public sectors. So even though sharing in the regime means that people can equally participate in the government, it relies on the principle of can rather than have to.[8] Every citizen has the opportunity to participate in government, as is given by their political equality, but their private freedom ensures that they don’t have to if they don’t want to. This gives rise to the freedom of non-compulsion, which is the protection granted by private freedom that the absence of compulsion guarantees people don’t have to fight wars, rule, and judge if they wish not to.[9] Despite democratic men enjoying the freedom given by this regime, they don’t have to engage in protecting it. Law could step in as a way to encourage people to participate in government, but it would then have the character of compulsion, violating the citizens’ freedom, and not meant for a democracy.

Law also plays a crucial role in democracy’s demise, specifically the law of equality, because it refers to the democratic man equally pursuing any pleasure that comes along.[10] These pleasures come as if they’ve been chosen by lot and the democratic man hands the rule of himself to it - fostering all those pleasures, good and bad, on the basis of equality. This connects back to how democracy was founded on political equality because the sharing of the ruling offices is similar to the pleasures sharing the ruling of the democratic man, both done on an equal basis.[11] The pleasures are also chosen by lot in the same way the offices are given by lot. Thus, Socrates can characterize the political equality described at the founding of democracy as the law of equality.

The law of equality attaches itself to the democratic man who treats good and bad desires alike.[12] It’s an equality of pleasures because the man lives day by day gratifying the desire that occurs to him and neglecting everything else, treating each surfacing desire with that moment’s attention.[13] And since the democratic man sees the lack of order as a free life, he constantly moves from whim to whim, doing nothing substantial in any sector of public or private life.[14] He lives his life with a certain equality of pleasures he’s established, dishonoring none, because he doesn’t see a difference between good and bad desires.

While Socrates mentions the law of equality and freedom in the context of the relation of the sexes, under the argument made, this law refers to the equality of desires and a man’s freedom to pursue whichever desire pleases him. So the conditions set up by private freedom in which democratic men treat every surfacing desire equally, lead to the collapse of the law of equality into the law of equality and freedom.[15] This is related to claims of political equality and private freedom because the latter gives men the license to do whatever they want in their private life and the former establishes equality through things being given by lot - in terms of offices and pleasures.

Democratic men being attached to the law of equality and freedom, which allows them to pursue whichever desires please them and then to treat such desires equally, permits a descent into tyranny. A transformation from a democracy into tyranny occurs because of this regime’s focus on freedom and neglect of its other values.[16] The democratic man is greedy for freedom because democracy defines it as good–democratic men are constantly told that democracy is only worth living in if people are by nature free[17]–and such greed also dissolves it. So the private freedom given to people corrupts and transforms into the worst version of itself - ultimate freedom.