Text

Defining Religion in the Law: Improving Modern Legal Systems

Source: https://bahaiteachings.org/infallible-balance-morality-religion-law/

Judges have been entrusted to interpret the religious and irreligious without the required education for too long now. The current format is counterproductive, and the court’s decisions have proven to be inconsistent.

The Church of Scientology is now considered to be a legitimate religion comparable to Christianity, Islam and Judaism in the eyes of the law. In the case of Hodkin 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that Scientology could be classified as a religion under the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855, which now allows Scientologists to lawfully solemnise marriages. In the case Regina vs Registrar general 1970, it was found that a chapel of Scientology was not a place of meeting for religious worship under that same act. This displays a clear inconsistency in the court.

In Hodkin, Lord Toulson described religion as,

a spiritual or non-secular belief system ... which claims to explain mankind's place in the universe and how [followers follow] the belief system.

Toulson did not intend to define religion, but this case will likely be invoked in future cases under common law should no definitive definition of religion be established. This effectively places the ruling of religious cases on quick sand. A lack of objectivity encourages religiously concerned definitions and decisions to be made by those that are not qualified to do so.

No resolution is clear, but the problematic nature of the current legal framework is evident. On the other hand, the Equality and Human Rights Commission in a Report 2016 explain that the current framework sufficiently protects all eligible religions and, when ambiguity is met, precedent set in case law should be invoked. This is not supported by Toulson, who did not set out to establish a precedent in Hodkin; as he states his definition of religion ‘is intended to be a description and not a definitive formula.’ According to Toulson, deciphering the eligibility of a religious organisation based on case law is insufficient.

The legal definition of religion is contentious which in turn affects legal exemptions and eligibility permitted to organisations, religious or otherwise. International, regional and national human rights law permits the right to freedom and manifestation of religion, offering no definition. Oppositely, English law offers various definitions across existing areas of law (Sandberg: 2016).

Pollock (2007) writes that the ‘legal definitions of ‘religion’ for charitable purposes is under difficulty because the current law, established in a Christocentric context is being strained by emerging minority Western and non-Western religious groups. Current religion laws are outdated in modern pluralist society, the legal religious terminology requires reassessment as it fails to sufficiently protect religions outside of Christianity, due to its close ties with Western Culture.

Sandberg argues that a ‘preferable approach would ... adopt a generous definition of religion.’ Conversely, it would be suitable for modern religion law to interpolate secular belief systems alongside religion by means of adding a broad but effective definition of ‘belief.’ Or, more radically by replacing ‘religion’ in statute law with ‘belief’ alone. This is discussed specifically in my other blog. ‘Belief’ suitably encompasses all paths of human commitment, whether they be political, ethical, moral, scientific, religious or other. Although this would negatively render a lesser position to religious persons and organisations in the law, which may result in further persecution and marginalisation.

The issue and solution surrounding the definition of religion in modern legal statute is unclear. Courts would be well advised to maintain judgment based on precedent set in case law. Meanwhile, research should be undertaken for the aim of establishing a definition of religion for statute law that represents all eligible religious organisations beyond those embedded in the Western legal system.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Belief’ or ‘Religion or Belief?’ A Modern Change in Current Human Rights Law

Source: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pauldoranlaw.com%2Fdiscrimination-religion-

Could human rights law (HRL) on ‘religion or belief’ be made more suitable for modern plural society by dropping ‘religion’ and using the term ‘belief’ alone? This approach would build on article 9 and article 18, a general reform of religion law would not be necessary.

Cranmer summarises a 2015 review of equality and HRL law by concluding that ‘belief’ merits further assessment. The broad definition and relationship between religion and belief is unclear. An argument could be made for the sole use of ‘belief’ in the law. Belief sufficiently encompasses both sacred and secular life-stances, making the law more succinct, accessible and in keeping with modern, pluralised society.

In light of the suggested change, one has to consider that religiously fuelled persecution persists despite religion’s overt protection in HRL. The removal of ‘religion’ within HRLs would be counterproductive, likely leading to further discrimination on religious grounds. Religious groups have been subject to prejudice, alienation and marginalisation in recent times despite such laws protecting their freedom to believe and manifest their beliefs. This factor should be considered in any reassessment of the law.

Neither Articles 9 or 18 specify who is eligible for protection; the duty is left to the courts. The ECHR define belief based on a precedent set in McClintock [2008]. It states that for a belief to be protected it must show sufficient cogency, seriousness, concern important aspects of life, be sincerely held and be worthy of respect in society. This definition is adequate in that it covers eligible human beliefs, but it should be made broader as to not unnecessarily exclude any beliefs, allowing for clarification in court. A broader definition of belief would be mandatory in a scenario where ‘belief’ replaced ‘religion or belief.’ But, this could negatively lead to the misuse of the legal system for lawful protection of non-genuinely held beliefs or those that compromise HRL and seek to cause public harm.

A broader, preferable definition by Pollock explains that a belief must make claims about the world we live in and human life and draw implications for the way one lives and establishes a basis of morality and values. This definition is positive in its total coverage of religious, philosophical, ethical and political beliefs; which are equally deserving of legal protection under HRL.

Under the current law, secular belief systems such as Veganism, for example, have achieved legal protection. The first instance of a non-religious belief being protected under The Employment Equality Regulations (2003) happened in Grainger 2009. The claimant achieved protection of his environmental beliefs, which affected his life and constituted a genuine belief. This points to the benefit of the standing ‘religion or belief’ laws which have enabled for the protection of secular and sacred belief systems alike under judicial interpretation. Such incidents establish a precedent that will be referred to in future cases. Therefore one should ask, are the current laws sufficient?

Definitions in modern legal framework are sufficiently broad in that they ensure the protection of all worthy ‘religions or beliefs’, and where difficulty is faced, judicial interpretation and case law may be invoked to settle dispute and uncertainty. Recent case law and evolving societal views suggest that protection under ‘religion or belief’ is working and perhaps even improving in its validity. Current religion or belief law, for the most part protects genuine life-stances, whether they be considered religious, non-religious or irreligious. As it stands, ‘religion or belief’ statutes in the legal framework work sufficiently in pluralised society.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Separating Church and Sovereign: Just How Religious Should the Next Coronation Be?

Source: https://www.google.com

Imagine that the next Royal Coronation was the first of a new nation and aimed to represent all religious and non-religious populations. It makes no sense to champion one belief among various present. Should the faith element be removed or altered to fit in with modern British society?

Why is it considered reasonable to overtly include the Church of England (CoE) in the next Coronation? This is partly due to the religious dimensions of the last Coronation, which resembled the Anglican population of the time. This no longer the case.

The undisguised inclusion and direction of the Coronation by the CoE was appropriately representative of the British population at the time. The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II (1953) was a day that affirmed the ties between the CoE and the Monarchy. The Queen swore to ‘maintain ... the Protestant Reformed religion ... as by law.’ Inclusion of the crown, sceptre, orb and robe are reminiscent of Christian iconography of saints and Jesus. This establishes the Sovereign as an integral element of the Church.

According to the Constitution Website, the next Coronation will be an Anglican service, in Westminster Abbey involving other faith groups, although primarily Christian. This is comparable to the Diamond Jubilee service or Prince Harry’s Royal Wedding which found places for ‘other Christian Denominations and religions’ (Kapusta: 2020). This suggests minor positive changes that do not go far enough and fail in representing the modern, pluralistic British public.

An appropriate approach would include all religious and non-religious beliefs to a certain degree. A publication by the Woolf Institute, Cambridge (P28: 2015) concluded that the next Coronation ‘should ensure that the pluralist character of modern society is reflected’ in order to acknowledge British diversity.

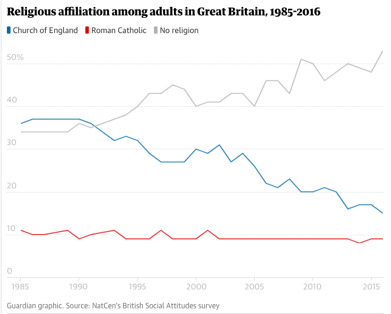

Findings from a recent 2016 survey (graph 1) shows that non-religious association in British adults overtook that of the CoE in the early 90s. A 2011 census found that around a quarter of the British population reported having no religion at all. To be representative of its majority population, like the last Coronation, statistics suggest that the next Coronation ought to be secular or religiously and non-religiously plural in nature.

Graph: 1

A secular Coronation might include officiating roles for state representatives such as the PM and members of Parliament. Religious symbology can be replaced by symbols of the state and nation. An oath to ‘protect the faith’ can be replaced by an oath to ‘protect the nation and all of its inhabitants.’ This approach, although progressive is unlikely and perhaps non-desirable to the public regardless of its representativeness of the majority population. This could be due to the prominent ties between the CoE and the state and British culture, which many would not want to see dissolve. A medium approach between secular and sacred inclusion should be employed.

A ‘middle ground’ Coronation might include multi-faith elements from Britain’s most populous religious groups, established in the 2011 Census, as well as members of the state, who represent the non-religious demographic. This fits with a proposal from Prince Charles who asserted favour in being dubbed defender of ‘faith’, not ‘the faith.’ This positively ensures the Monarch’s recognition of non-religious groups as well as religious denominations beyond the CoE. The effects of this could go as far as maintaining the relevance of the Monarchy and promoting social cohesion and assimilation among a largely pluralised British population, who would feel represented and recognised in a diverse ceremony.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illegal Humanist Weddings: The Decade Long Fight for Legal Recognition

Source: https://twitter.com/humanistwedding/header_photo

Humanists are being denied legal marital status under the Marriage Act 1949. As the law stands, Humanist weddings are permitted but are not legally binding, unlike religious weddings ceremonies (Sandberg: 2020). Religious ceremonies included in the act are Quakers, Jews and of course, the Church of England. The act is not in keeping or representative of the religiously and non-religiously diverse, pluralised British population of the 21st century.

Baroness Meacher stated in the House of Lords in June 2020 that 6,000 couples have had to have a second ceremony to lawfully solemnise their marriage. This compromises the human rights of Humanists and reflects an issue that has been campaigned on for decades, since at least 1999. This leaves one pondering, why have no changes yet been made?

Six Humanist couples stood before the High Court in an attempt to attain the legal recognition that their marriages rightfully deserve. Couples explained that a humanist ceremony is deeply linked to their identities and that the law devalues their beliefs. This goes against the current human rights law which protects the right to manifest one’s religion or belief under Article 9 and Article 18. Furthermore, the claimants offered to settle the case in the light of the pandemic, which the Government refused. In the couple’s hearing, Judge Eady ruled that the current law gives rise to discrimination, but failed in determining the current status as unlawful due to an ongoing review of how and where couples can legally marry in England and Wales. The Law Commission Review was published in September 2020 and will now be considered by Parliament. All signs point to the legalisation of Humanist marriages in England and Wales, that which will see them follow the more progressive and modern laws in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Despite the seemingly consensus view that Humanist marriages should be given legal rights, no changes have yet been made. Parliament had given the Government the power to amend the law seven years ago, which they have not, claims Humanists UK. Following confusion surrounding the allowance of Humanist marriages during the pandemic, the Government confirmed that Humanists can continue to perform and have the same number of attendees at ceremonies as religious ones. This confusion did not affect religious marriages.

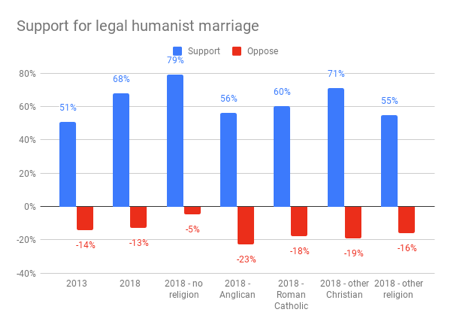

Humanist marriages are less likely to end in divorce and are now supported by nearly 70% of the British public; by religious and non-religious people alike according to a recent YouGov Poll (graphs 1/2). The YouGov poll consisted of only 2,038 British adults, which does not constitutes a consensus opinion for the entire nation, despite that claim from Humanists UK.

Graph (1): https://humanism.org.uk

Graph (2): https://humanism.org.uk

The number of Humanist marriages has positively soared in Scotland and Northern-Ireland, where they have recently been made fully legal. Humanist Society Scotland provides more marriage ceremonies than the Church of Scotland and in 2017, 8% of legal marriages were humanist. The Humanist Association of Ireland are only behind the Catholic Church and civil marriages, displaying the extent to which the society has become plural and modernised.

The legal issue boils down to a case of amendment. An Approved Organisation Bill has been made which offers a section in The Marriage Act 1949 allowing ‘an authorised belief organisation [to] perform marriages,’ which specifies Humanist UK. This piecemeal reform would maintain the illegality of those who wish to be lawfully married according to non-organisational beliefs, explains Baroness Vere of Noribton. The best course of action, therefore, is a total reform of the Marriage Act 1949 in keeping with the pluralised 21st century British population.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Legal Bias and Religious Symbols: When the West Meets the East

Source: https://www.american.edu/ocl/kay/images/Interfaith-Banner-Icons-1310.png

We are all so familiar with symbols. They instruct us one a day to day basis by conveying a meaning or instruction. This encompasses everything from locating an ‘on’ button on a remote control to recognising recyclable materials according to three green arrows. Such succinct secular symbols are unproblematic. This is untrue of religious symbols which convey deeper, ethical and philosophical meanings.

What might appear to be a mathematical instruction to one might convey Christian beliefs to another and equally on could interpret the symbol used to represent Buddhism for the steering wheel of a sea vessel. Ambiguity is never far away when deciphering the meanings of religious symbols. The impact of those ambiguities in identification can have a severe impact for religious freedoms when brought to the legal sphere, in which some religious symbols, usually Christian, have gained legal protection and others, usually non-christian, have not.

Source (Cross):https://www.pngkit.com/png/detail/939-9395164_to-christianity-transparent-background-white-cross.png

Source (Dharma Wheel): https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Dharma_Wheel.svg/1024px-Dharma_Wheel.svg.png

Courts around the world have been entrusted to not only permit or forbid the use religious symbols in society, but to define their meaning (Scharffs, B: 2012, 35). This is an audacious task given the intrinsic, personal and subjective nature of religion, which uses symbology as its primary mediator in society. Courts have rightly expressed an unwillingness to allocate meaning to religion and religious symbology given that it will set a precedent for future cases. In Hodkin Vs Registrar General 2013 the Judge offered a sufficient definition of religion to fit the context of the case, but asserted that it was ‘intended to be a description and not a definitive formula’ and in Begum v Denbigh HS, Lord Bingham explained that it would be inappropriate for the court to decide whether ‘Islamic dress should be permitted in [UK] schools.’ Thus, displaying the hesitancy of the court in such rulings.

The Islamic veil (all forms of Muslim headcovers (Van Engeland, A: 2019, 214)) has been a topic of dispute in world courts. See Begum v Denbigh HS or Karaduman v Turkey for primary examples. The Western judicial system view the veil as being forced upon women in order to display their subordinate societal and religious roles, a prominent factor in Western Colonial belief (Ahmed: 1992, 149) which is the basis of the French full-face cover ban (Bacquet, S: 2019, 66).

Source (veil): https://static.vecteezy.com/system/resources/previews/000/565/828/non_2x/hijab-vector-black-symbol.jpg

Investigation according to sociological studies find that the reality purpose and persuasions towards donning the veil are contrary to expectations. Van Engeland argues that the veil is a ‘liberating tool,’ acting as a metaphorical passport between the private and public spheres (Van Engeland, A: 2019, 217). Bacquet found that in some cases, Muslim parents discourage their daughters from wearing a veil, extremely opposing Western legal consensus opinion (Bacquet, S: 2019, 65-66). Had these approaches been applied in relevant cases to gain an insight and understanding towards the purpose of wearing the veil, exceedingly different outcomes would have been reached. This approach would be applicable to other religiously involved legal cases, improving on current legal approaches in the courts.

References:

Ahmed, L. (1992), Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate, Yale University Press.

Bacquet, S. (2019), Religious Symbols and the Intervention of the Law: Symbolic Functionality in Pluralist States, Routledge.

Scharffs, B. (2012), ‘The role of judges in determining the meaning of religious symbols’, in Temperman, J., ed. The Lautsi Papers: Multidisciplinary Reflections on Religious Symbols in the Public Classroom. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff.

Van Engeland, A. (2019), ‘What if? An Experiment to Include a Religious Narrative in the Approach of the European Court of Human Rights’ in Journal of Law, Religion and State, vol. 7.

0 notes

Text

This is Why the British Public Do Not Want Shamima Begum Back in The Country

Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53427197

Shamima Begum of East London left Britain in 2015 to join ISIS and has since been dubbed as a ‘ticking time bomb’, ‘ISIS Bride’, ‘a member of ISIS’, opposed to a ‘Jihadi Bride’ and many other negatively imbedded titles.

The overwhelmingly consensus dislike of Shamima Begum is single handedly down to one British journalist, Anthony Lloyd. Begum explains in an interview that she believes that the decision made by the Government to retract her citizenship was determined by her interviews with journalists. On the 24th November, during Begum v Secretary of State 2020, Barrister Eadie argued against Begum’s return by directly quoting Begum’s interview with the Times. This establishes how influential Lloyd’s report was in determining Begum’s future and public appeal, which has proven bleak thus far.

The Times offered the first of an endless flurry of negative news media reports of Begum which would include little to no mention of her being groomed, brain washed and raped from the age of 16. In February 2019 Lloyd published two articles (1, 2) via The Times that set a precedent of animosity and otherness towards Begum which has shaped her media coverage and influenced her public perception.

Lloyd includes a voice recording of a conversation between himself and Begum in which he pushes for controversial soundbites. Lloyd baits Begum into positively recounting her experience with ISIS by asking if living in Raqqa (‘Capital of ISIS’) was an ‘experience which fulfilled your aspirations?’ Begum mentions witnessing a ‘beheaded head in the bin’ and being unfazed by it but showing remorse towards the death of her two children, explaining that ‘it was so hard.’ Lloyd explains that Begum was contradicting herself, as though a refugee camp was a standardised environment for a media interview. How coherent would one’s recount be following years of mental and physical abuse? Responding to Begum explaining that she was due to give birth imminently, Lloyds asks if Begum thought that the ‘caliphate was ending?’ No sympathy or understanding is offered throughout the report, Lloyd instead choses to highlight the narrative that Begum was connected to the terrorist organisation.

As a professional journalist, Lloyd will have known that his report would shape the perception of Begum as well as influence her appeal to return to Britain for the medical sake of her unborn child, who later died. The journalistic practice of Lloyd’s articles should be condemned. That which lead to the national demonisation of a young woman on the basis of her being targeted by a malicious organisation. Lloyd would have been well advised to report in this light, seeking advice and input from Islamic representatives and relief organisation such as tellMAMA,* emphasising Begum’s victim status.

In order to improve Western news media’s representation of Islam to the end of social cohesion, Muslims must become involved in their own reportage. They should present themselves as a nation of culture and civilisation (Mesic: 3). Writing in Croatia, Mesic likely sees Western society as the epitome of those ideals, thus implying that Eastern Muslim countries become more Westernised, which is deeply problematic and in keeping with current media practice.

Negative reports however did not taint all opinions of Begum. A writer for Islam21.com called Conservative MP, Rees-Moggs’ opinion of Begum being ‘innocent until proven guilty’ and having been ‘sinned more against than sinning’ as ‘some logic in the mob.’ Therefore, suggesting that the MP’s opinion, although fair, is in the minority.

In the most recent news, the UK Supreme Court will consider whether Begum will be permitted attendance to her own appeal (November 2020) to overturn the decision to deprive Begum’s citizenship. The course and media coverage of which should be spectated thoroughly.

*(MAMA of “tellMAMA” is an acronym for Measuring Anti-Muslim Attacks).

2 notes

·

View notes