Text

Developing Methods to Address the Platform Economy: The Politics of Shopify and Ecommerce

This is a shortened version of the SSHRC postdoc application I completed and submitted last week. Big shout out to David Neiborg who helped me with this. Even if I don’t receive the award, this broadly outlines the direction of my research. I’m going to keep publishing and working in and around game studies, but I also want to pivot a bit and dip into new topics related to Canada’s burgeoning tech economy.

Background and context

This proposed post-doctoral research examines a series of case studies on Shopify, an Ottawa-based e-commerce company whose spectacular growth over the past decade has continuously impressed the Canadian business community (Silcoff, 2017). Shopify provides the online platform which small to medium sized merchants (both brick and mortar as well as online) use to process sales and payments. In 2013, Shopify was the first Canadian “startup” to reach a one billion-dollar valuation (Silcoff, 2013). A year later, The Globe and Mail named Shopify’s CEO, Tobias Lütke, “Our Canadian CEO of the year you’ve probably never heard of” (Cole, 2014). By 2017, this valuation had jumped to 10-billion (Silcoff, 2017). This study will document Shopify’s spectacular growth in terms of revenue, customers, and what can be perceived as its growing dominance (with 500,000 businesses reportedly using the service) in digital commerce (Shopify, 2017). In other words, why has Shopify grown so much, so fast, and received the support of both private and public groups? How does Shopify work as a platform, and how it is changing how Canadians labour and produce value? Finally, I ask what Shopify signals more broadly for the future of communication on and around the internet.

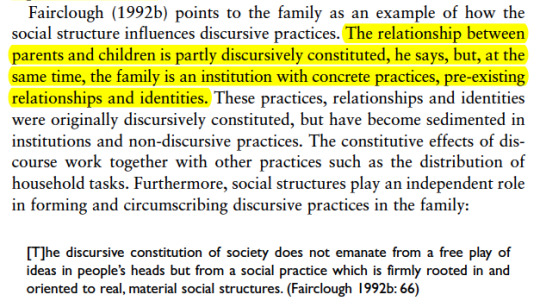

In addition to producing original research on Shopify as a distinct platform, while highlighting its relevance to communication, media, and cultural studies, I will develop and refine new quantitative and qualitative methodological approaches that address the specific particularities of platforms and “software as service”. I will build on the work of methodologies explored by Langlois & Elmer (2013), José Van Dijck & Nieborg, (2009), and Fenwick McKelvey (2011). My own contributions to this area include my doctoral dissertation on the political economy of Steam (a digital distribution platform for video games), a comprehensive analysis of the internet as a spatial fix for the circulation of capital (Greene & Joseph, 2015), and an analysis of how online communities were dispossessed of their hobbies by platforms, and how they resist that dispossession (Joseph, forthcoming). My research expands on established empirical methods like discourse analysis (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002), document analysis (Bowen, 2009), and thick description (Ponterotto, 2006). Importantly, Shopify has not yet been the subject of critical scholarly inquiry in media and communication studies. This project and its series of case studies intend to address this gap and provide perspective on a rapidly growing business and its place in the Canadian economy.

As one of Canada’s most successful “startups”, Shopify began in 2004 by selling snowboards online, while simultaneously developing the tools (interface and point-of-sale software) that would become the mainstay of its business. Shopify rhetorically positions itself as “making commerce better for everyone” by both providing what they argue are accessible tools, and by increasing the speed at which commerce can take place (Newton, 2016; Shopify, 2015). In other words, Shopify wants to build the technology that will have a hand in the process of “spatialization”, the abolishing of time and space as limits to the circulation of capital (Mosco, 2009). While much of Canada’s digital economy is dependent on monopolies headquartered in the United States, Shopify seems to be Canada’s success story, and its own monopoly-in-waiting. As such, analyzing Shopify’s ascendance is relevant for policy makers and businesses, and serves as a case study of what the future of the Canadian economy might look like.

Shopify’s business model also has serious implications for democracy and politics at a worldwide scale. In October 2016, Breitbart News Network, a far-right political website with close ties to the white supremacist “alt right” movement as well as the Trump presidential campaign, opened an online store to sell branded merchandise. This store was made possible with tools provided to them by Shopify. On February 2, 2017 it came to light that behind the scenes at Shopify, numerous employees were “quietly urging” management to end their business relationship with Breitbart (Daro, 2017). Six days later, Shopify’s CEO, Tobias Lütke, published a defense of Shopify’s official stance to continue supplying ecommerce tools for Breitbart. Lütke stated that: “products are speech and we are pro free speech. This means protecting the right of organizations to use our platform even if they are unpopular or if we disagree with their premise,” (Lütke, 2017). Shopify found itself in conflict: employees and critics pointed out that by providing tools for Breitbart, they were “endorsing hate”. Yet according to Lütke’s professed fidelity to classical liberalism, a private company had no right to restrict speech — in this case, the buying and selling of products — of others. This public relations crisis surrounding Spotify and Breitbart is just one example of the increasing conflicts that are made apparent by the growth and increasing monopolistic status of digital platforms in the world of ecommerce (Srnicek, 2017).

Digital platforms such as Shopify act as intermediaries that offer governance frameworks and facilitate business interactions (Evans & Schmalensee, 2016). However, those who own them discursively frame their operations as neutral, while in practice they have the power to restrict the flow of products and speech (Jørgensen, 2017; Langlois & Elmer, 2013; Napoli & Caplan, 2017; Van Dijck, 2013). In other words, these platforms often have more direct power over speech and commerce than the states whose rules they profess to follow, and exercise this power when it is convenient to them, and within what they consider ideologically consistent with their corporate, or in the case of key executives, their personal values (Dror, 2015; Hoffmann, Proferes, & Zimmer, 2016). Research on the future of platforms like Shopify must take into account that these governance frameworks will frequently be confronted with a broad set of discursive, legal and economic contradictions.

Related Literature

This project builds from my dissertation, “Distributing Productive Play: A Materialist Analysis of Steam” (Joseph, 2017). In it, I foregrounded how platforms are distributed technical systems that have human values built into them, and in the process, produce new (as well as reinforce existing) social hierarchies. This work is in line with existing research in platform studies, software studies, and political economy (Helmond, 2015; Langlois & Elmer, 2013; Montfort & Bogost 2009). This body of work has, in its own way, addressed the ongoing process of monopolization, control, and centralization at the heart of the digital economy. I chose to study Steam because it is the world’s largest distributor of games on the PC, and it hosts a variety of features (marketplaces, forums, content databases) that make it a site to investigate platform power, politics, and tension among consumers, producers, distributors, and workers.

My research is firmly located within the tradition of platform studies research in communication and cultural studies — what Canadian scholars Ganaele Langlois & Greg Elmer (2013) break down into three major approaches. The first comes from critical political economy, which addressed concepts like “immaterial labour” (Hardt & Negri, 2001), “semiotic capitalism” (Berardi, 2009), “digital labour” (Terranova, 2003), and “cognitive capitalism” (Moulier-Boutang, 2012). The second tradition came out of critical empirical engagement with platforms in software studies, and used methods that practitioners considered to be “native” to the technology (Helmond, 2015; Rogers, 2015). Finally, Langlois & Elmer (2013) argue that the last tradition emerged from media activism and software design, which focused on theorizing and finding concrete solutions to the problems that were raised by critical political economy or software studies (Lovink, 2012). Elmer & Langlois (2013) saw that all of these traditions for studying platforms could be productively unified by stressing that each focused on different moments in the production of communication and culture.

The study of platforms involves a host of political and methodological challenges. Platforms are driven by corporate, profit-seeking logics, which set distinct limits on what researchers can hope to understand and know about the platforms they study. Elmer and Langlois (2013) argue that critical social media research must always contextualize the degree to which platforms are enmeshed with these logics. They argue that “Corporate social media platforms obfuscate: their logic goes against critical approaches at many levels… (p. 8)”. The data that these platforms produce is far from objective; instead it merely records “corporate and participatory logic” (p. 10-11). As such, the researcher of a social media platform must move forward asking this: “how can we unpack the different articulations of corporate and participatory logics by examining what is available to the researcher with limited access to corporate social media data and to the social media algorithms that organize life online?” (p. 14) This is the tradition of research in which I position this proposed study.

This research also theoretically addresses some of the most important dynamics at the heart of a critical analysis of capitalism. In the decade since the crash of 2008, and the subsequent Great Recession, many of the core theoretical arguments in Marx’s (1867) Capital vol. 1 have garnered serious attention in both the public and in communication studies (Fuchs, 2012a; 2012b). One of those is the dialectical relationship between concentration/monopoly, and competition. I want to continue to test and theoretically challenge the core principles of critical political economy by making an empirical contribution via my investigation of Shopify, and how it conforms to and deviates from these dynamics. Shopify has done an excellent job of creating a monopoly in the midst of a very competitive marketplace; how well will it fair, when profits could easily be squeezed or decline? Will there be a repeat of the dot-com crash of the late 1990s? Is the enthusiasm around Shopify’s business model simply a repetition of the rhetoric of the “digital sublime”? (Mosco, 2005) This is important for the future of the Canadian economy, especially if it wants to base its future on tech companies like Shopify, which have yet to post a profit.

Methodology

In addition to producing original research on Shopify — a Canadian business with impressively rapid growth that has received scant scholarly attention to date — I will develop and refine new quantitative and qualitative methodologies to address the specific particularities of platforms and “software as service”. To do this, I propose to conduct a series of case studies concerning different “moments” that together make up Shopify.

The first case engages with the platform at the discursive level, analyzing popular representations of the company in the press and by employees and executives (Hoffmann et al., 2016; Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002). Here I am interested in answering the question of how Shopify has been discursively framed and written about in the press that is most read, and presumably, most influential, to Canadian investors. At stake here is also the discursive construction of “platform” in the press, which Tarleton Gillespie (2010) has argued is a political exercise that frames the wider public discourse around these technologies. I will begin by conducting a discourse analysis on media representations in Canada’s major business newspapers, The Globe and Mail, The National Post, and the Toronto Star. I will build a database of stories with significant commentary on Shopify, code each using NVIVO, and analyze them until I reach saturation in terms of themes and discourses (Rogers, 2015). Understanding the discursive positioning of Shopify in the popular media adds to a broader understanding of Shopify’s valuation in the stock market, and the conflicts that arise around the company’s public behaviour.

The second case is located at the level of the platform’s user interface, mobilizing Shaw’s (2017) proposed mixture of Stuart Hall’s (1980) encoding/decoding framework in dialogue with James Gibson’s (1986) affordance theory, which “looks at the encoding/decoding of designed affordances to better account for power, resistance, and interactivity in digital media environments” (p. 2). In other words, I will analyze what Shopify does and does not afford both users (those who shop in digital and brick and mortar stores using Shopify’s services) and subscribers (the customers of Shopify, who use it as an ecommerce business solution). The goal is to “not simply point to how power is operating, but work toward subverting existing hierarchies and finding the hidden affordances of hegemonic processes” (p. 9). From a user perspective, this means finding online stores that use Shopify’s tools, and interacting with them. From the customer side, this will involve semi-structured interviews with small business owners who use Shopify’s tools, possible supervised visits to Shopify’s Ottawa and Toronto offices, and structured experiments with using Shopify’s tools to run a personal store for myself. To do this means subjecting Shopify to a variety of conceptual typologies, and utilizing thick description’s ability to contextualize space and technology (Ponterotto, 2006).

Finally, as a scaffold for the above cases, I will use document analysis (Bowen, 2009) to investigate Shopify’s assets, mergers, partnerships, board members, and revenues. In other words, I will conduct a network analysis using principles from political economy (Mosco, 2009). This analysis will contextualize the company’s growth, strategies, and its place within the Canadian economy to answer how Shopify is both unique (historically) and itself a product of a cycle of concentration, competition, and fragmentation. Moreover, these cases can be addressed by the theoretical toolkits provided by critical political economy, which takes a holistic (and often implicit [Meehan, Mosco, & Wasko, 1993]) qualitative approach to technology and the economy (Hardy, 2014; Mosco, 2009). At the same time, within this framework, there is an undogmatic approach to the specifics of each method, working inductively and re-triangulating as new challenges arise and as conditions and historical moments change (Elmer & Langlois, 2013). In light of this, my goal is to develop and refine existing methods of analysis so they become highly effective tools for the study of “software as service” platforms. This will help move the field beyond the study of social media (Elmer & Langlois, 2013) or hardware consoles (Montfort & Bogost, 2009) toward traditionally “hidden” platforms like Shopify.

Bibliography

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

Cole, T. (2014, November 24). Our Canadian CEO of the year you’ve probably never heard of. Retrieved September 14, 2017, from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-magazine/meet-our-ceo-of-the-year/article21734931/

Daro, I. N. (2017, February 2). Shopify Employees Want The Company To Stop Doing Business With Breitbart. Retrieved September 5, 2017, from https://www.buzzfeed.com/ishmaeldaro/shopify-breitbart-store

Dror, Y. (2015). ‘We are not here for the money’: Founders’ manifestos. New Media & Society, 17(4), 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813506974

Evans, D. S., & Schmalensee, R. (2016). Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

Fraser, L. (2016, April 4). Could Toronto-Waterloo be the next Silicon Valley? Retrieved September 5, 2017, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kitchener-waterloo/silicon-valley-toronto-waterloo-1.3519032

Fuchs, C. (2012a). Dallas Smythe Today - The Audience Commodity, the Digital Labour Debate, Marxist Political Economy and Critical Theory. Prolegomena to a Digital Labour Theory of Value. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 10(2), 692–740.

Fuchs, C. (2012b). With or Without Marx? With or Without Capitalism? A Rejoinder to Adam Arvidsson and Eleanor Colleoni. TripleC (Cognition, Communication, Co-Operation): Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 10(2), 633–645.

Gibson, J. J. (1986). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Classic Edition). New York City: Psychology Press.

Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms.’ New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738

Greene, D. M., & Joseph, D. (2015). The Digital Spatial Fix. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 13(2), 223–247.

Hall, S. (1980). “Encoding/decoding.” In Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-1979. London: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies.

Helmond, A. (2015). The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 2056305115603080. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080

Hoffmann, A. L., Proferes, N., & Zimmer, M. (2016). “Making the world more open and connected”: Mark Zuckerberg and the discursive construction of Facebook and its users. New Media & Society, 1461444816660784. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660784

Jørgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications. Retrieved from http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?url=http://SRMO.sagepub.com/view/discourse-analysis-as-theory-and-method/SAGE.xml

Jørgensen, R. F. (2017). What Platforms Mean When They Talk About Human Rights. Policy & Internet, 9(3), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.152

Joseph, D. (forthcoming). The Discourse of Digital Dispossession. Games and Culture, (Ludic Economies).

Joseph, D. (2017). Distributing Productive Play: A Materialist Analysis of Steam. Toronto: Ryerson University.

Langlois, G., & Elmer, G. (2013). The Research Politics of Social Media Platforms. Culture Machine, 14(0). Retrieved from https://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/view/505

Lütke, T. (2017, February 8). In Support of Free Speech. Retrieved September 5, 2017, from https://medium.com/@tobi/in-support-of-free-speech-275d62670203

Marx, K. (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. (B. Fowkes, Trans.) (Penguin Classics, Vol. One). Penguin Books in association with New Left Review.

Meehan, E., Mosco, V., & Wasko, J. (1993). Rethinking Political Economy: Change and Continuity. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 105–116.

Montfort, N., & Bogost, I. (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

Mosco, V. (2005). The Digital Sublime: Myth, Power and Cyberspace (first). The MIT Press.

Newton, D. (2016, May 19). Make commerce better for everyone. Retrieved September 13, 2017, from https://ux.shopify.com/make-commerce-better-for-everyone-b96f0621ddf3

Ponterotto, J. G. (2006). Brief Note on the Origins, Evolution, and Meaning of the Qualitative Research Concept “Thick Description.” The Qualitative Report, 11(3), 538–549.

Rogers, R. (2015). Digital Methods (Reprint edition). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Shaw, A. (2017). Encoding and decoding affordances: Stuart hall and interactive media technologies. Media, Culture & Society, 1–11.

Shopify. (2015). Page Speed: Are Slow Loading Pages Killing Your Growth? Retrieved September 13, 2017, from https://www.shopify.com/enterprise/60726275-page-speed-are-slow-loading-pages-killing-your-growth

Shopify. (2017, August 1). Shopify Now Powers Over 500,000 Businesses in 175 Countries. Retrieved September 13, 2017, from https://www.shopify.com/press/releases/shopify-now-powers-over-500-000-businesses-in-175-countries

Silcoff, S. (2013, December 11). A rare startup success story: Shopify hits $1-billion milestone. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/small-business/sb-money/a-rare-startup-success-story-shopify-hits-1-billion-milestone/article15892998/?arc404=true

Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform Capitalism (1 edition). Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity.

van Dijck, J. (2013). The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford University Press.

Van Dijck, J., & Nieborg, D. (2009). Wikinomics and its discontents: a critical analysis of Web 2.0 business manifestos. New Media & Society, 11(5), 855–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809105356

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

hi tumblr, I don’t really use you anymore. HIiiiiiiIi

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gabe Newell: Reflections of a Video Game Maker

So just a quick note. This is a transcription of a talk that Gabe Newell made at the University of Texas LBJ School of Public Affairs in 2013. This is the most accurate transcription I could make in the time that I had, and it’s not perfect. There are some names and phrases that could be incorrect, so just keep that in mind. I transcribed this talk so I could conduct a discourse analysis on it, specifically for my second chapter, which focuses on the Steam Store. There’s a lot of interesting stuff that Newell talks about in here, and it reveals a lot about the general strategy that Valve is still pursuing with Steam. Of particular interest is that it sheds some light on the fallout of the paid mods debate, and that at one point Newell was looking into implementing “prediction markets”, which were first floated as an idea to challenge socialist central planning by Hayek and von Mises, the architects of neo-liberalism. I wonder if they didn’t implement them because they are considered a form of gambling in most countries.

Gabe Newell: So I’m Gabe… and valve was founded in May 1996. We’re a privately held company and that’s actually a consequence of other decisions that we made, that I will touch up on later. We made single player games like Half Life. Multiplayer games like Team Fortress. We built an Internet Services Platform called Steam that has 55 million users and 25 hundred different applications running on it.

The question would be, other than my charming personality, is Valve interesting? Right? Why is Valve an interesting company? If you use super gross metrics it sounds like it could be interesting. We grow over 50 percent a year, and have since we started the company. We can make people very productive and they have a lot of value. So if you look at Apple or Google or Microsoft we have a much higher revenue in profitability per employee than they do. And you know we generate more internet traffic than most countries, right? I think we are the fourth largest bandwidth consumer in the world right now.

So that says that something’s happening here, but is it interesting beyond just being another company that makes a bunch of money? Well my path, which I’m going to use to illustrate, I’m going to walk you through what I learned and how I learned applies to Valve and motivates the choices that we’ve made, and what, if any, significance they have.

So I was at Microsoft from 1983 to 1996, I started working with Macintosh applications and switched over to operating systems. Now one of the things was that in 1983 I was at company called business land. Business land is an answer to a trivia question nowadays, but at the time they were the biggest seller of PCs to small businesses in the world. And they would take 50% of the gross revenue of the sale. So somebody like Osborne would sell them a machine for a $1000, and they would market it up to $2000. If you flash forward to 2012 often times games are sold at negative margins at retail. So we will sell a product to retail and they will sell it to consumers for even less. So why are they hoping that maybe they will generate some foot traffic that will help offset the negative margins of selling something that is likely to attract people’s attention? Maybe they will buy some blank CDs or something…

So what happened? Why did this part of the value chain lose so much control over the whole process? And is it generalizable? Is it a unique instance or symptomatic of broader set of trends?

My own experience in answering that question started in the early 1990s. So Microsoft had no idea what was happening in the real world with our products. We would have reseller lists. So you would sell your product, somebody else would take your pallet that you would physically send them, and they would sell the individual product up to lots of local stores. Those resellers represented one small fraction of the total product being sold. They had nothing to do with anything other than the North American market. So we would post these reseller lists where they would tell us what products were selling out of their warehouses and that was pretty much the complete insight into how our products were selling in the real world. So product managers would obsess over relative notions of one or two spots on the top ten lists. But the idea that you would know what was happening from an OEM channel, or happening with corporate accounts, or happening anywhere outside the United States was more or less science fiction.

This was a well run company in the early 1990s.

So at one point the applications group had to make a bunch of decisions. Like you know, these crazy Windows guys, they’re saying that windows is doing super well, but Lotus is telling all their corporate accounts that the sales numbers are all fake, and that people are not adopting windows in any significant way. This was going to materially impact how quickly they were going to move their products over to windows rather than character based.

So Microsoft commissioned this rather large study where rather than looking at the sales side of it, or the resellers side of it, they would actually go out into the real world and see what people were actually doing. It was the first time Microsoft had done it. It was to look at 10k people’s machines and figure out what they were actually using PCs for.

Turns out they were using them for porn and video games. That part of the study was immediately ignored. But the good news was that if you extrapolated those numbers was that Windows was actually being used on 30 million people’s PCs in the United States. And this was cause for enormous celebration. “Thank god they are actually using it” rather than just getting it shoved onto their dell or compaq machine and immediately uninstalling it and going back to character mode dos.

What was really striking to me at the time was that Windows was the number 2 product and probably most of you know what the number one product was.

Anybody?

It was Doom.

Doom was one of the first first person action games made by a company called ID, a company in Mesquite, Texas. So somehow the biggest software company in the world was being out-distributed by a twelve-person company in Mesquite, Texas. And there was no conception, there was no model for why this made any sense. How could they have possibly done that? It had taken years to build up distribution strength to go up from number 7 to number 6 in the word processing category. Much less come out of nowhere with a product that would be on more desktops than the most important product that Microsoft had.

And at the same time that Doom was out there with a completely different approach to connecting users with value, people within sight of Microsoft were arguing that we needed a five hundred person, you know, Rob Glaser, who would go on to found Real Networks, was saying we can be competitive with Novell Netware until we hire a five hundred person sales force and all they were going to do is sell LAN Manager to the resellers. They weren’t even going to sell to customers, they were investing in an indirect channel making this giant, building this giant organization that continues to live on within Microsoft all these years later. Who were not actually directly involved in making that sale.

That was the landscape at this point in time. There were two other interesting data points. There was another company that was called Ventura, who made Ventura Publisher. Have any of you heard of it?

It was the same kind of thing as Doom. They were the first people that I ever met with who explicitly said retail distribution and marketing is a commodity, and we’re not even going to bother investing in it. Instead we’re gonna build a great product, and once we have a great product we will turn around and put it out to bid. Who will give us the best percentage? They eventually ended up with Xerox, and Xerox eventually proved that sales and marketing aren’t quite as commodified as the Ventura guys had thought they were, and probably underperformed what they thought they could.

But they said, “let’s ignore all this other stuff, it’ll actually make this worse”, we’ll just focus on the thing we do super well, and this other thing is gonna become declining in value constantly.

At the flip side of it was the IBM PC junior, and the interesting thing about the PC junior at the time, and i Guess it was 1987, it was that the burden cost of shipping empty box by IBM was over the retail price of PC Junior. In other words, they couldn’t possibly be profitable, ever, selling products in that category. Their choices about the organization, their investment in direct corporate sales, the way that they had structured themselves financially made it impossible for them to even move an empty box - a nothing - through their inventory process into their customer’s hands.

So both of these things make one start to think about what’s going on. In what will certainly be a shortcut to the conclusion (which was that there were structural changes that were affecting the relative value of business functions), and that whole categories within typical corporations were essentially being made obsolete. That communications to your customers were on an exponentially decreasing cost curve. That everything was associated with talking to a customer, delivering a product to a customer, and this would be true if you were delivering in virtual products, or a physical product, it would just be more obvious when you had low marginal, low incremental cost, low costs for incremental production, all the costs associated with building a video game, tend to be associated with before you sell your first copy. Selling your first copy, +1, is relatively cheap. This would be just as true for selling John Deere tractors as it was for selling video games. It would probably be more testable, more provable, in spaces where you can easily see the low friction delivery of a good didn’t involve significant incremental costs.

So what did that mean when you’re designing a company? This was the question I was trying to answer in 1996. We would go out and meet with all these companies. We would meet with insurance companies, and airline companies, and startups in silicon valley, and you had to come up with some way of thinking what the design was.

What we became convinced of, the character who’s the other founder and myself, was that everybody was going in the wrong direction. There was a movement towards outsourcing. Outsourcing is where you try to find the lowest cost english speaker somewhere in the world and will give them a job and they will do it, just as well for a lot less money. To us that seemed just exactly just the opposite of what you should be doing, so we decided that we were gonna buy the most expensive talent that was out there in the world. The opportunity was, those were the people who were least correctly valued. By talent, which is a word I hate, just means the ability to be productive.

Now one of the things that sorta helps people in the software space think about this is that its relatively easy to look at relative productivity of people in that space. So at IBM in the 1980s typical productivity would be a thousand debugged lines of code shipped per year. That was the metric they used for their median employee. Whereas when we were shipping Half-Life 1, 1 employee Jean (Berget?), was shipping 4,000 lines of code per day. So there’s pretty clearly, it’s easy to see that there’s, even if you’re not arguing about who’s lines of code were more useful, and it’s pretty easy to see that Jean’s lines of code were more useful than arguably somebody developing a 3270 terminal emulator for OS2, even if you’re just looking at the raw production, its easy to see that there’s huge variation in productivity.

One of the huge tenets that we used was that there was probably true across a much wider range of functions. So we started from the assumption that even though it was easy to see that there was a huge variation of productivity in software programmers, there was probably that same variation in a lot of other roles. So when we designed valve, ok so that’s what we’re trying to do, everything goes back to this fundamental question, how do we attract and maintain the most highly productive people in the world? Because if our thesis is correct, that’s where were gonna create our greatest incremental value. We could hire a whole bunch of, there’s a big thing where a couple years ago, where everybody was trying to hire low cost content producers in India and China, and we’re trying to do the opposite. We’re saying that somebody somewhere you know, somebody working on the feature film production in New Zealand is making 200k a year. If they come to valve they should be making 500k or 5 million dollars creating that much value, and we split the difference, and go from there.

So there are consequences of those choices. Nobody is asking questions, which has me a bit worried…

The consequences. One: Valve is not a publicly traded company. Being a publicly traded company comes with a lot of headaches, and it didn’t really solve any problems for us. Right, it meant that control and decision making now involved third parties. So for developer building something at Valve, there’s the customer, and there’s the person you’re trying to make happy. From the time that you make a change in a product, its 15 minutes worst-case before a customer is actually using that. There’s no approval process if you make a bad decision its 15 minutes until you’ve fixed that problem. You don’t go to board meetings, where the board argues about what the series, third series of venture capitalists are worried about. Delusion in hitting certain targets, no notion of distribution channel who says were really looking for something that fits into this particular slot at this particular time. The whole point of being a privately held company is to eliminate another source of noise in the signal between the consumers and the producers of a good.

One of the other things is that the kinds of people that we thought fit this model don’t need titles. Right? That titles are actually the enemy. Their enemy, rather than something that makes them more productive. Often times there’s solutions that are different in one generation than solutions in the previous generation. That specificity organizations captured in titles makes it less likely for them to have the insights and build for the next generation of whatever it is that’s going to be exciting. The great example from half life one, is that the guy who designed the skeletal animation system also had a bachelor of fine arts and also could build environmental art.

So if you go to a movie nowadays, the idea that you would have a single person doing much more than a subset of any of those roles is mind boggling. That there’s a set of experiences that you get in half life 1 that are entirely a consequence of the person working on it being able to change the environment, change the code, or change the animations, depending upon what was the most tractable way of solving the problem. So titles in organizations keep people from properly encapsulating the problem at a point which allows them from being most productive.

audience member: concerning the flat hierarchy of Valve. Was that something that you had in mind at the creation of Valve? Or did it arise as you were working?

Gabe Newell: This was a part of the design of the company from the beginning. One of the other things along the same lines... the thing that people, to us, we've been working this way for a long time. So it doesn't seem as nearly as peculiar to us as people outside. So another thing that might take people by surprise is that management is a skill, not a career path. We assume that everybody is a mix of individual and group contribution and there are a set of tasks that look like, or evolve over time or a project or an organization to keep things going. Usually people refuse to do it twice in a row on back to back projects because it is very much a service job: "My job is to entirely define myself in terms of the productivity I enable in other people.” That's a very stressful job and it's hard to measure your own productivity. Everybody else is like “Hey Jay, you did a great job. You should do it again." and Jay is like "Screw you guys."

So usually we look for some younger sucker to give the job to. We think that, you know, you have some old notions about management and authority within a hierarchy related to decision making and then they find out it's working really really hard to make other people be more productive. So if that doesn't blow you mind. We have no QA department. We have no marketing department. We have one guy who calls himself a Vice President of Marketing, because it confuses people if he doesn't tell them that when he's talking to them. Everybody at the company we assume it's their job to talk to customers.

audience member: How are you able to hire and retain this sort of talent you're looking for.

Gabe Newell: A lot of times it was just personally pitching people saying "This is why we think it's an interesting opportunity". Some of the people we thought were going to join us at the beginning didn't. We were like "Let's go, let's storm the castle..." and then it was like… "Where'd everybody go?"

So once you convinced people you were doing something interesting, then they would start to rope in their friends. A lot of it ends up being social networking at the end of the day. John Carmack was pretty helpful at getting us going. Michael Abrash was another guy. We're also willing to take what other companies would say are "risks". So one of the first programmers to the company, his previous job was manager of a Waffle House. And he was one of the most creative, and still is, one of the most creative programmers in the industry.

audience member: programming costs have gone up since half life 1 - has it changed the way your company works?

Gabe Newell: Our company evolves all the time. So I'll try to give you an example of how we evolve. I am the big believer in the "one person, one office", DeMarco's 'PeopleWare', if anybody's read that? I treat that as a bible. I hated cubicles with a passion, with a vengeance. They grew out of this dated general philosophy of "if you're screwing your employees you're probably doing something right". I was like, "OK, everybody always has their own office." You got a do not disturb button on your phone and a door you can close and you can decorate your office however you want. And people kept sneaking into other people's offices. And then they started tearing doors down. So everybody had their own office, but nobody was ever in it. They were all these clusters of people in our conference rooms. That's when I realized they were making the right decision. They were deciding that there were benefits to being in closer proximity to other people. That Gabe's rigid adherence to one person one office was actually hurting their productivity. So after being hit on the head long enough I realized that everybody else was making a decision that was correct for them, so now we just say "everybody designs their own office space". So our largest single room has about 80 people in it. I share an office with two other people. That each person has to... that's one of the things you think about, you think about how you communicate with other people. You think about what's an optimal work environment for the goals you have. Decks are all on wheels. We only have two contact points on the floor, so you can pack up and join a different group of people in 15 minutes. Some people are working on the design of... if anybody has done paired programming there's some people trying to build the desk for paired programming. They had to make the decision where it was more worth their time to work on something like that than it is to do the work they already are.

So we just said that each person has to make their own decisions about what they work on, who they are working with, what are the tools they need and what their offices ought to look like. That's how we evolve, usually by people deciding that I have a bad idea. Another thing that became very important sort of later on but is pretty much perfect for the design of us now is that if you're not making quantitative predictions you're probably doing it wrong or you're not doing it as well as you can. That's sort of become kinda critical to how we operate. You have to predict in advance. Everybody can explain anything after the fact, and it has to be quantitative or you're not being serious about how you're approaching the problem.

audience member: What are some of the problems you have encountered with the flat hierarchy?

Gabe Newell: You have to be very aggressive about firing people. We haven't done a really good job with interns or new hires. It's kinda a sink or swim thing. People have to take it seriously. it's an engineering problem in the sense of "you have to make decisions, you have to measure outcomes, you have to make changes as a result of it." I would have trouble working any other way now. I think most of the people at Valve would have trouble. There's something we call, something we unkindly call the "beaten wife syndrome", where people come in from other industries, and really struggle. The worst are people from the feature film industry. Where they have been sort of taught that any time they show initiative that somebody's gonna leap out and smite them for doing that. And so that can usually take people from six to nine months for people to sorta internalize the working model. Those are some of the things we've encountered.

audience member: do you think that's why other businesses don't' follow your flat business model? It's sorta a personal responsibility type of thing?

Gabe Newell: I’m gonna come back to how I think things are changing and why I think things are changing so when you come back to it you may have a different way of asking it.

To get onto that subject, these issues are gonna collide in a couple slides.

So, how do we make a single player game? The single player game was the challenge that we first had when we were building Half Life. How do we make any decisions? People say we should make games more realistic, and we sorta went down that rabbit hole, and it turns out that it's a horrible horrible design trope to use. So we had to come up with this notion that games are things that respond to agency on the part of the player. The player performs an action or has a state, you need to recognize that and respond to it. It's a fairly abstract way of saying, if i shoot at a wall something should happen. So when we started with Half Life your gun would fire but the wall wouldn't change. The wall was essentially ignoring you. Then we put a decal in it and testers would go and spend an hour drawing things on the wall with their machine guns. We said "Ok, so this looks like a useful heuristic for making game design decisions." In half life 2 a piece of technology that was really hard that turned out to be super valuable was in modelling how people's eyes work when they are looking at you. So eyes are not spheres, so when your eye's rotating, you're gonna see something, the highlights, the glints on your eye are gonna move differently than if you modelled them as spheres. People, it turns out, you have a part of your brain that's hardwired to know where somebody's looking. Even though somebody's looking in the second realm, I can tell when they're looking in the third realm. So spending the time to make the characters aware of where you're in space, and that they're looking right, correctly, at that person. it turns out that people suddenly say "Oh these characters are nicer. These characters are more like me. These characters are smarter." So something as irrelevant to a "game" is making eyes look right, can generate the sense that this game is more fun. That's how a heuristic can lead to interesting conclusions.

Now of course, all of this breaks down when you're trying to build a multiplayer game. Now a single player game is like a feature film where your lead actor is retarded and autistic. You can think of it as a feature film. Now a multiplayer game, these rules that you sort of come up with don't work anymore. So for example, in Counter Strike we put the riot shield in, and player numbers go up. We take the riot shield out, and our player numbers go up. So how do you explain that? You need a different way of thinking about what you're doing. So you start to think that after a while that multiplayer games are more about externalities, they look more like operating systems, or a sport. So in terms in how they behave, they behave a lot more, and they value is created, a lot more like a spectator sport than a feature film. So that's pretty cool. The problem was, jump forward a couple more years, this great model we had for thinking about single player games or multiplayer games, seemed to breaking down again. So there are a couple interesting examples of that. One is free to play games. So on the surface free to play games seem like a horrible idea. I will give my product away for free. Most people just sort of stop right there and go "Oh, Ok, that's horrible." But in a free to play game what you're really doing is you're creating a lot of goods that are related to status, and affinity, and hierarchy. What you're creating is a a whole bunch of goods there. And the marginal, the incremental value of an audience member is greater than the incremental cost of making that person an audience member. So typically what we see with a free to play game, which typically sounds like suicide, is that your audience size goes up by a factor of ten and your gross revenue goes up by a factor of three. So the cost of another audience member is fairly small just the cost of distributing those bits to those customers, you're profitability tends to increase a lot more than a factor of three.

Thats sort of puzzling. and then we start seeing this thing occurring in lots of sorts of games, where we have markets and auction houses. See you have trade in goods between different customers. So you have this sort of appalling thing that happens where somebody will play your game for 20 hours a week for four years and then the value of all that goes to zero. So it's like you bought a house, and you made a bunch of improvements on the house, and when you moved to your new house, you have to start over. You get no value from the investment that you've made. Clearly these markets and auction houses are valuable. Or that the assets that you've accrued are valuable to you enough to justify this tremendous expenditure of your time, the game seemed to have this really whimsical notion about your property rights. We're all seeing this huge uptick in user generated content. To be really concrete, ten times as much content comes from the user base for TF2 as comes from us. So we think that we're super productive and bad ass at making TF2 content, but even at this early stage, we cannot compete with our own customers for the production of content for this environment. So the only company that we've ever met that kicks our ass is our customers. We'll go up against Bungie or Blizzard or anybody, but we won't try to compete with our user base. Because we already know that we're gonna lose. Once we start building the interfaces for users to start selling their content to each other we start to see some surprising things.

So right now I think that the most anybody has earned in a single year is about 500k, so they're making content, selling it to other customers, and we have a revenue share with those people, and their take away was 500k. The first two weeks that we did this we actually broke pay pal because they didn't have. I don't know what they're worried about, maybe drug dealing? Nothing generates cash to our user base other than selling drugs like this. So we actually had to work something out with them, saying "no they're making hats". But now that we have this notion... oh another thing that was weird, we knew that people at other companies, other game companies, were making more money, as users in our framework, than as employees at these companies. So we were like, OK, this is weird. And then it got more complex because we started to see inflation, we started to see deflation, we started to see users creating their own versions of currencies, mediums of exchange, countries started to create regulatory structures. So in Korea you had to create the equivalent of a W4 form for your players, to account for the virtual income they get. So you get like, wait, should we increase the drop rate for those customers to offset the implicit tax, the income tax, and what do we do about purchase price parity? Should we adjust drop rates to provide welfare to people in low income... or do we drop the value of their drops to reflect the fact that they can trade their hats for cheeseburgers, for fewer... how do we decide how we are creating productivity in this environment. You start to see trade, trade is exploding even though currently it's a barter economy. We sort of had problems with liquidity where at different times of day certain mediums of exchange dried up and all the sudden you had weird sorta mini financial crises happening in your weird TF2 hat exchange.

So when we started to see these kinds of issues is when we decided "Oh, we should start talking to an economist."

audience member: inaudible... about the value of goods that "don't exist"

Gabe Newell: I don't think the value for that is very different from lots of other kinds of status goods, or you know... or why do people buy Porches? So I don't think there's anything super different about how value gets created. If you look at money. Well people say "well these things aren't real" and you go "well what about money" and they go "that's not fair". So one of the things you have heard me say is that we're trying to optimize productivity, and that requires you start thinking in terms of productivity in terms of "what". So it is an issue that we're struggling with now. How do you think about what is the value and how do you feel like you're not creating you know... asset bubbles... are something that worry us. This is where hopefully an economist...

We also believe, I'm also of the belief that there are a set of initial conditions that have different outcomes and that by putting in different kinds of structures we can avoid different kinds of turbulence subsequently.

audience member: (inaudible)

Gabe Newell: So what we think is that you need some sort of market. Our job is to maximize productivity of users in creating digital goods and services. The markets will determine what the marginal value add of each of those activities are. The kinds of ways in which people create value and creativity… and creating frameworks for that are gonna vary. You can't just define productivity in terms of shit you give to a customer because then you just miss the whole opportunity... if you're just raining hats onto your customers eventually you're going to suffer huge inflation and so on. So the way to think of it is that there's probably gonna exist a central, I'll just gonna use the term "economy" that gains are all sort of instance dungeons hanging off of that. And within a game I'll be able to create goods and services that I'll be able to exchange with other people in other games. Some of things ill be able to do is go "Hey, I got this hat", and somebody else will get to say "I actually designed that hat" and that the person who designed that hat is gonna be a higher value person than the person who simply traded or acquired this asset in some other form. So you're gonna have a bunch of different ways that people are gonna be creating things.

One group of people will be simply arbitraging, creating opportunities and creating liquid markets in hats, right? But other people are saying Ii'm gonna build a game, and my game contains animations and models and environments" and the steps were taking right now are to build this notion of ownership and authorship throughout the entire system. So I’ll be able to create something in one game and exchange it for value with somebody else. So everybody I think can understand this notion of creating a model of exchange. That's a fairly easy way to think about productivity. But in another way taunts and animations are also ways in which you create value. But we also think that something like being a really good player is something valuable for the community. And the challenge isn't that we have created value, the challenge is coming up with a monetization method for those people. So in Dota2 we say "Here's NaVi". NaVi's one of the best teams in the world, they are from the Ukraine. In particular one of their players named Dendi is one of the most charming people in the world. How many people know who Dendi is? Ok. So when Dendi is playing or NaVi is playing you can purchase a banner and depending upon the outcome you may or may not be rewarded with an item for showing your support and a percentage of the banner revenue goes to the team. It turns out that it's a really great way for the team to monetize the entertainment that they are creating for a bunch of people. Right? So we're looking for ways to say "Dendi your'e awesome you're entertaining and so on, and rather than trying to sell ads on your youtube channel, here's a much more direct way for you to engage with your audience and for them to also benefit from waving your banner while their playing. So pretty quickly we'd expect somebody like Dendi to be making a 100k through banner sales for his team a year. For us that says "Ok we think this is valuable, people are spending money, Dendi is gonna spend even more time doing entertaining things like playing Chrystal Maiden (inaudible) with Five Blade Furies, which if you're a Dota person sounds ridiculously cool. And if you're everybody else it doesn't.

So the things that you do in these games need to have persistence and they need to be exchangeable and we need to look at more ways to users to generate content to be productive in this audience. To accumulate assets that are exchangeable and that retain their value. So an example of that is - I'm gonna jump ahead in my own slides. To talk about concretely about ways in which we instantiate this new understanding of what we're doing. So right now Steam is essentially a curated store. Right? It's a bunch of other things but you can also think of it as a curated Store. So we have these really hardworking people that other companies call up and say "Hey would you put my game on Steam" and they say “Oh uh we're putting up three games a day now and we have to do this capsule and blah blah blah" and essentially whether we want to or not we are becoming a bottleneck in terms of content being connected with users. Now there are reasons why you might want to create an artificial bottleneck, for example if you want to shift where relative value is towards controlling distribution which is great at creating artificial shelf space scarcity. But that's not really what we're trying to do. Rather than having this curated store if we're thinking about this correctly is that it should really be a networked AP. There should just be this publishing model, and yes you have to worried about viruses and malware, but essentially anybody should be able to publish anything through Steam. Steam is just a whole bunch of servers and a whole bunch of network bandwidth and if people are interested in consuming the stuff you're putting out there that’s a good... a collective good is going to be there. Rather than us sitting between creators and consumers, we're gonna get as far from that connection as possible. So Steam stops being this thing where you call up Jason Holtman and yell at him to get your game on Steam Store and instead it just becomes a network API. So that's a consequence of our perception of where the industry is going.

On top of that we also say that right now have this... in TF2 we say that anybody can make content. You can make goofy ushankas for all the characters. I didn't even know that word until I saw them appear in TF2. There's no notion of privileged content. Right now in Steam the store is privileged content. The store is a collection of editorial perspectives on stuff, and what it should be is user generated content. That means that other companies might create their own stores that are connected to the Steam back end, but anybody will be able to create a store. There's some market based mechanism determining the price the store gets to impose, so if anybody tries to charge too much for the goods that fall through that store will get priced out of the market. But if you have a collection of games that you own and play, and if one of your friends decide to buy a game through your trivially created store, you should get a percentage of that revenue. So most people won't have interesting collections of games or interesting friends or I dunno, but some people will go to a lot of effort to create treating a store as another type of experience. Some people, the guys that I would have loved, Old Man Murray would have done an awesome job. Yahtzee would probably be another person where either through affiliation or through his editorial process you could purchase a product through him rather than some other way.

So you take two things that you think of as super valuable assets that have to be guarded really carefully, deciding who gets to be on Steam and deciding how stores are presented to consumers, this is how we re-think them. It's a generalized network service, and a store rather than a unique special thing that represents Valve having control of this and rather it turns into lots of people creating really entertaining stores, adding a lot of value to that process, and through the market mechanism it will justify the audience... the audience will reward or not reward people for building entertaining stores. Does that make sense? Where we take these sort of high level concepts about how we're gonna change and turn them very concretely into a set of product changes and system level changes.

As I said before one of the things we had to do was plumb through this notion of authorship and ownership and if I build a texture and somebody builds it into a model and if somebody takes that model and if somebody builds it into a level and if somebody else sells that level to a customer, whatever revenue share that I should get depending upon what are the terms that I provided to other people to use it, all that has to be tracked and accounted it. And it means that we need to spend a bunch of time building these frameworks that help and enable people to be productive and to be rewarded accordingly. Even with our primitive versions we are helping people at other companies be more productive than their corporations are doing it. But we're constantly thinking about what are the ways and what are the most useful, fundamental, ways of enabling that productivity. One of the topics that Yanis and I are working on right now is making prediction markets something that are easy to people to author and easy for people to participate in. We think there is a huge amount of value on both the entertainment side and on the information capture side of having prediction markets and we also think that once everybody is used to having prediction markets they will be very beneficial tools. I'm absolutely certain of prediction markets going up that prediction markets will be vastly more reliable than a typical game publisher's own predictions and market forecasts for their own products. So I bet you could take 20 gamers, build a prodiction market and nail the call of duty black ops 3 sales numbers much more accurately than any of the market services that we use. So there's an example of something that we're currently missing, that would be hugely valuable to the economists, if one of the prediction markets is GDP targeting, my personal favourite, it would also be entertaining if some of the prediction markets are "how long before Lindsay Lohan goes into rehab?"

audience member: information, do you already have the data for this stuff?

Gabe Newell: We have lots and lots of data but analysis of data is hard. We want to take all the data and make it as widely available to people as possible. Right? if building a hat is valuable analyzing data from Steam is gonna be a lot more valuable. So anything that we do we're trying to figure out how to systematize a framework for our audience to participate. I do my job better if I figure out how to get reddit to do my job. I do it a lot better, right?

audience member: potential security, hackers doing mean things, etc

Gabe Newell: First of all, there are multiple kinds of hacking. So one of the biggest mistakes game developers make is mistake a genuinely entertaining action by a player as "hacking". So the example game developers tell each other is when Lord British was killed during his first speech in Ultima Online, they rolled the world back rather than recognize that it was the coolest thing that had ever happened in Ultima Online. They should have let that instance turn into whatever it had turned into after they had killed Lord British. So one, you have to be really careful. Second you have to be... it's a general characteristic of social systems that people have to have confidence in that future. That's true whether it's your house, whether the stuff inside your house, if property rights are provisional, than your valuing of property changes accordingly. So Yanis and I were talking about neighbourhoods where the homicide rates are incredibly high compared to, say, North America, and you'll see the consequences of that lack of security throughout the entire...

So yes, its important, yes there are a whole bunch of technical problems to it, and to the degree to which you fail to provide adequate security, those consequences will ripple throughout the entire world. Meta world.

audience member: (inaudible).

I would say that releasing source as a goal to increase productivity has not been one of our more successful efforts because its just not a... it limits the ways in which people can participate and add value. It's hard. It's too hard for most people to incrementally get into it. One of the ways we think about it, is that being a member of this economy is to think of it much more like an MMO. You need to walk people through step wise, here are your questions, buy a hat, sell a hat, sell ten hats, oh look you got an 11th hat when you sold your 10th hat. Now make a colour change to a hat. Walk people up in the same way MMOs walk you up in how you experience and the ways in which you participate. That's the way we think of it, that growing people in this economy looks a lot like walking people through an MMO experience.

audience member: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for market participation

Gabe Newell: They do it for both. They get a lot of cash, they get a lot of other rewards as well. We're not trying to separate those rewards. The way we think of it is that money needs to flow as a signalling tool. That's if people want to do something because their friends think its cool. That's still gonna be there. But in order for people to assess if what they are doing is valuable or not, you need currency so they can go "oh wow i made ten times as much money doing this rather than this." So the signalling has to be comparable. So why do corporations exist in the first place? If you're an economist one of the challenges is to explain why we do we need corporations at all? Why isn't the price mechanism sufficient to allow good organization of production and allocation of capital?

So why are the PC and internet important? They create frameworks for innovation and competition, and one of the most important consequences is that variations of Moore's law that are making not just computation but communication and access to data exponentially cheaper, and those are continuing to accelerate, we all know that when things get computationally cheaper that's valuable but there are also consequences to communication and access to data getting cheaper. I have lots of anecdotes about that. One of the things from an economic perspective that's important to realize that cheap information reduces moral hazard, agency costs, and information asymmetry. The point that I make to people of who are of your generation - is that you can't lie to reddit. It's remarkable how many people try, but they don't understand that reddit's ability to detect bullshit in insanely high. But that from an economist perspective translates to something that's really incredibly important about information asymmetry and moral hazard. You'll hear me, people get confused when I sort of rag on consoles. "oh well you have a competitive platform blah blah blah. The thing i hate about closed platforms is - I can go into this ridiculous amounts - is that they increase the chunk size of competition. They increase costs of market entry, so that people who have good ideas, its actually a lot more expensive for their productivity to be monetized essentially in closed platform spaces. they also delay standardization. Standardization is a mechanism by which, well, if you ask me I look at the behaviours of most corporations, it looks like rent seeking behaviours on top of friction. Which is a really dark way of thinking about the roles people have in corporations. Standardization is a great way of illuminating the ability to rent seek. As is probably an entire permutation on itself. I would sort of say that to us in this room it seems fairly obvious that the internet does a better job of organizing a bunch of individuals than General Motors or Sears does. A lot of these company’s things were perceived as being capital assets end up disturbing their decision making so that they actually end up dooming those companies. I don't know how to do that in five minutes...

The bottom line is that corporations essentially look to me like pre-internet ways of organizing production and allocating capital. And that when you see things like makers, when you see the emergence of...

So I have a million dollar CNC. It's a hobby that kinda go out of control. Its a bunch of... so i thought "oh good, I'm gonna have a hobby it's got nothing to do with my day job." The reality is that all the problems of machining are all software problems. The problem of engagement angles look a lot like rendering problems. The difference between carving something out of aluminum and drawing something in 3d space are astonishingly similar. The way you keep this thing working is you standardize a bunch of stuff and create a network interface so jobs can flow through this thing and you end up making - this hobby of mine - ends up looking a lot like Counter-Strike in terms of the sets of decisions you would make to improve it. theres a temporary and intermediate state where the people who are machine tool sellers end up stop selling machine tools to people and end up selling machine capacity to a much wider audience. So machine tools are really cool, and if you end up adhering to a set of standards, and you set up an interface just like ttip provides a standard inter-networking protocol, it turns out that you can actually get a lot more stuff through one of these devices. So my hobby, annoyingly, looked a lot like my job. And sort of, let me use it in presentations like this, sorta took a little bit of the I'm gonna do something completely different out of it. I actually think that this notion about machining, which is sort of the most real world thing I could think of, with 3d printing now we got all the weight of microtransactions... arghhh even more like video games now. Where on demand you’re building custom items for an audience on a worldwide basis. There are already companies that don't even bother to sell you the hardware. They sell you the 3d models that you send to your 3d printer and the thing that you actually get from them is the software that's running on top of that. I think you're gonna start seeing a lot more businesses that look like that.

I think the pre-internet way of thinking of communicating with users as a sort of broadcast one size fits all way of thinking of products. Right now everybody thinks we're gonna get the same product. Our children are gonna say “Thats the weirdest thing they have ever heard of. Every one of my products are unique and different." and that transition means that the sets of lessons that we are learning today in the video game space are probably gonna be true about a much wider range of industries tomorrow.

Thank you.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Discourse of Digital Enclosure: Presented at the 2016 Canadian Game Studies Association @ University of Calgary

So I’m here to present some early results from the first chapter of my dissertation which is about the Skyrim paid mods controversy, which took place in the spring of last year. Last year I spoke a little bit about this topic while drawing attention to my article that I co-authored with Ian Williams at Jacobin which addressed some of the sticky political cleavages apparent at the time.

I began my dissertation about Steam with three with three questions that I can summarize here:

1. how does the platform reinforce and reshape how work and play are discursively understood and materially practiced?

2. Inside this meta-question, what is the scope and reach of Steam are as what Stuart Hall calls a “determinate moment” in the production and reproduction of video games as commodities?

3. Finally, I’m interested in the specific techniques, technologies and ideologies deployed on and around Steam to create work that appears as play, and play that appears as work.

This places my focus on two elements related Steam. The first is the language used to talk about what it does, and the second is the actual methods and techniques the platform allows and constrains.

The example of paid mods has both of these. On one side, I have the example of how community stakeholders discussed the program on reddit, on Nexus Mods (a popular mod hosting site), and the popular press. On the other side I have the platform’s tools itself, how it operationalized the sale of modifications.

For me, what I see when sifting through the discourse at play during this moment of upheaval is a great example of what Karl Polanyi did in his book The Great Transformation: show how there never has been, from the get-go, an unfettered free market between free, property holding individuals. That in fact the marketplace & the wider economy has always been embedded in already existing social relations: the state, private property, moral discourses, and their attendant relationships of force. In Foucauldian terms, the economy is awash in immanent relations of power. In Structuralist Marxist terms, the economy is that which determines (or more accurately, sets the limits), in the last-instance, the rest of social relations. In essence, the idea of the free market is a utopia, a non-place that is resorted to rhetorically, but that which is has never existed in practice.

In the case of paid mods, a huge player in all this is Valve, who own the digital property that modders will one day till, so to speak.

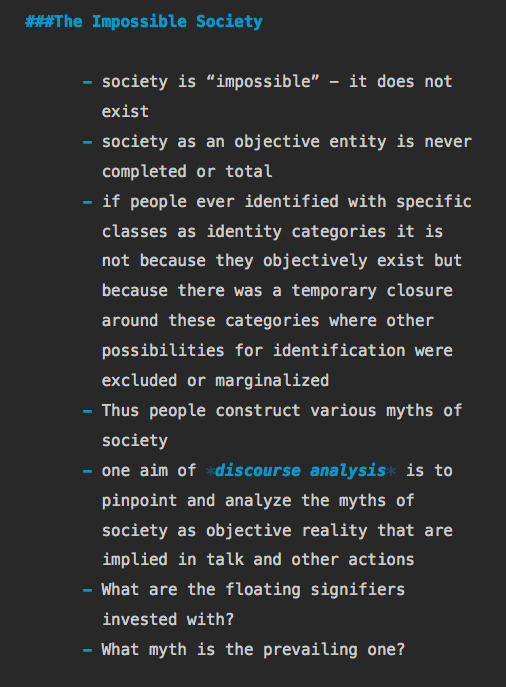

####Ontology, Epistemology, Method

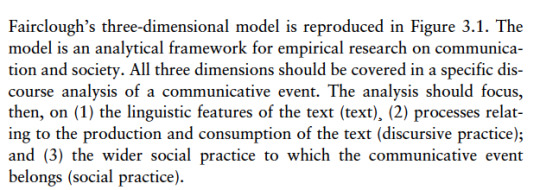

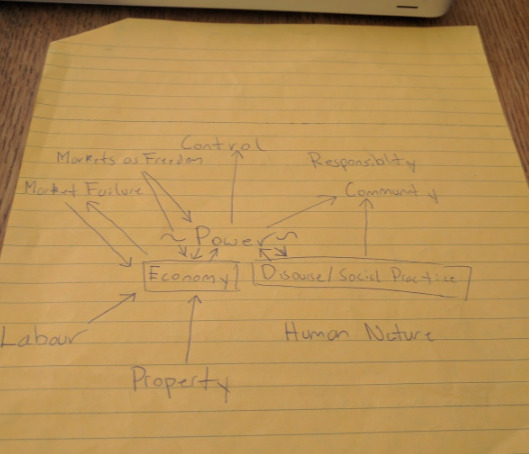

Here is an early drawing of a model I’ve been working on to make sense of social reality, when you’re considering discourse analysis as a method.

Kinda rough, right?

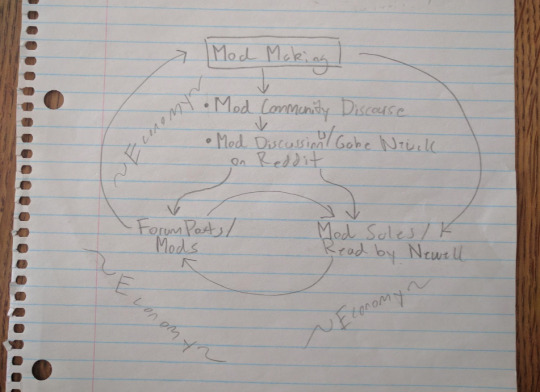

Here’s a second model, a little bit more linear.

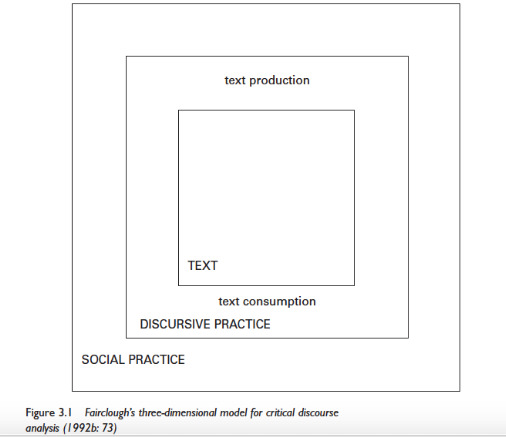

Which is actually a take on Fairclough’s model:

Here’s a more developed one:

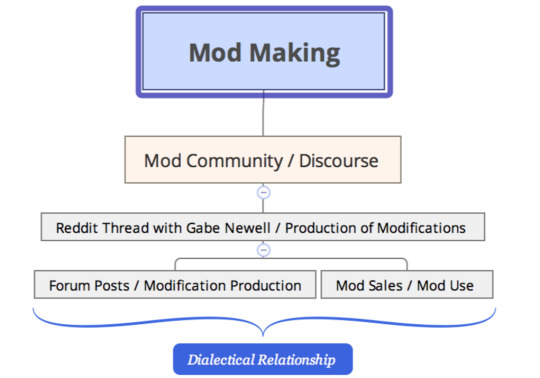

Finally, I ended up with this model:

Here I am attempting to map the discourse of mod-making, as understood by various stakeholders. These might be creators, consumers, and platform holders. Each node in the model is best described as a “moment” in a complex social process, when each step is a part of a great social sphere. The model begins with the social practice of mod creation, the concrete intellectual, social, and physical actions that have to take place to create an object known as a “mod”. This act, this moment of mod creation exists in a dialectical relationship with the discourse of mod making - the ways in which the creation of mods is both practiced, spoken/written about, and finally, articulated in relation to the economy.

Below, or, more accurately, inside, this node/moment is the textual practice that discourse itself is made up of of. I consider the re-creation of the mod itself a part of this discourse. I also highlight the ways in which stakeholders discussed and articulated their conception of mod making in the context of the explosion of passion around Valve’s 2015 decision to monetize mod production.

For the purposes of my study, I wanted to sample the kinds of discourse that stakeholders mobilized to criticize Gabe Newell, CEO and part owner of Valve Corporation, when he posted to reddit asking for clarification about the community backlash. In this post more than 18,000 comments were posted. Here, on one of the internet’s most traffic’d sites the billionaire CEO of a beloved video game company was regularly called greedy and stupid.

I used this reddit thread as a starting place to collect and reflect on the most commonly used phrases, arguments, and concerns about turning mods into discrete commodities. Relating back to the model, I see these posts and the sale of mods, as well as the production of an archive of community dissent as existing in a dialectical relationship, internally. This is the dialectical of production and consumption of texts.

This, in turn, exists dialectically with the social practice of mod making, all contextualized in the wider social field of global capitalism, which is fundamentally premised on sale of labour-power.

####Digital Methods & Analysis

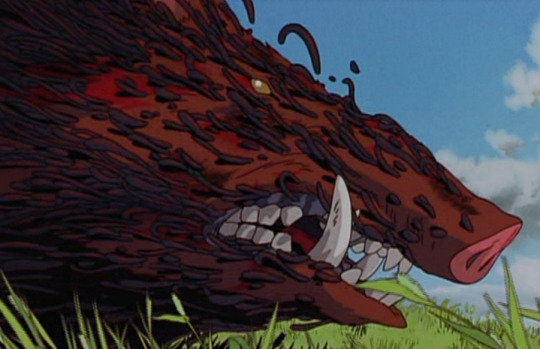

After sifting through hundreds of comments (show picture of some of them) I tried to create less than 10 broad themes and concepts. I ended up with these:

In critical discourse analysis there is a hierarchy of sorts the organizing discourse is called the “genre”. To make sense of this genre necessitates a theory of the space in which the discourse is moving, and in CDA this is - based on conceptualizing of the “space” where discourse functions as a “field”, in the Bourdieuian sense. A field has what Bourdieu calls “habitus”, made up techniques and discourses. For this chapter my field is the online space where the discourse takes place - so r/gaming - a reddit thread.

I will call this genre the “discourse of the online forum”, for the lack of a better term.

The ways in which r/gaming talks about the problem of paid mods are dictated by the platform the discourse takes place on: reddit. No doubt the way reddit is organized, moderated, coded, etc, effect the culture and discourses deployed on it.

Inside this genre lies the good stuff. The discourses that flow, encouraged and reinforced, during this debate.

How is the basic list of themes I coded for, after my first pass through the top 250 comments or so.

- commodification

- community

- property

- responsibility

- labour

- leisure and play

- consumer rights

- openness

- market failure

- markets as freedom

- illegitimate control

- legitimate control

& later, because on my second pass through the data I added

- greed

Let’s look at some examples of each.

Commodification: Any discussion of the the process of turning mods into a distinct commodity.

The problem is that by monetizing mods you’re encouraging developers to pander to the lowest common denominator. Look at National Public Radio. They air content that nobody else will because they’re not restricted to content that will make as much money as possible. People who wouldn’t ordinarily have an opportunity to voice their opinions, tell their stories, etc, can be heard.

Community: whenever I saw the idea of the mod-making community mobilized.

… by adding money to the equation you are fracturing the community that had grown up around TES (The Elder Scrolls) modding. I feel this may do serious damage to the entire modding community, and IMHO its a really bad move in total for PC gaming; since a real big draw to PC gaming is Modding.

Property: any mention of the ownership of mods, the ownership of the platform, etc.

I appreciate you cannot dictate what developers do outside and off of Steams services, but Steam is Valve's service, and you can control how your service is used.

Responsibility: this one was more vague than i liked. I was trying to track when people talked about Valve having a “responsibility” to users, mod makers, etc. Any responsibility, really.

Listen to your customers. Please. We don't mind supporting modders. But we don't want a paywall. Nobody wants a paywall. Have you seen the petition?

Labour: any mention of work or labour, any talk about creating things that stresses the process.