Text

El Quincenal presenta una entrevista con Pedro Noigandres y Bartolomé Delmar sobre Miodesopsias

1 note

·

View note

Text

EL QUINCENAL presenta DOS FORMAS por Alí Cotero

Alí Cotero

Imagen: Movimiento y descontextualización, oroorooro, 2018

0 notes

Text

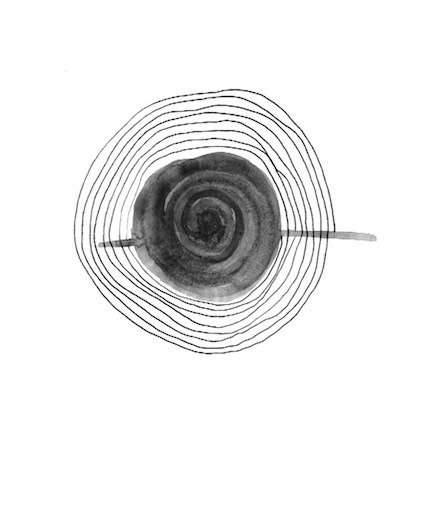

/ p o é t i c a s c o r p o r a l e s /

El Quincenal presenta tres poemas colectivos producidos durante el Festival Enclave, Poéticas Visuales 2018. Los poemas son apropiaciones de diversos textos científicos creados en una Clínica de Imaginación Poética impartida por Lucía Hinojosa y Victoria Gutiérrez. Estos poemas funcionaron como puntos de partida para explorar la relación del cuerpo ante la palabra, el pulso, y sobre todo, el giro.

autores: Abril Sofía Santana Ventura, Alejandro Vázquez Hernandez, Armando Alejandro Florero Olivares, Aura Aguilar Rodríguez, Cecilia Carrillo Luna, Cynthia Eugenia Pech Salvador, Denisse Granados del Valle, Edén García Reyes, Enrique Romero Cruz, Francisco Constantino Ramírez Quintero, Guillermo Iván Rocha Vázquez, Jonatan Montoya Hurtado, Jonathan Torres Rodríguez, José Noguero Ricol, María del Rosario Leyva Duarte, María Teresa Irazaba González, Mariana de la Paz Arabarco, Mariel Vela García, Mónica Gameros García, Omar Serrano García, Rebeca Martell, Rosa Ivette Tapia Silva, Rosana Amorina Zinni Tittonell, Tilsa Otta Vildoso, Uriel Isaac Palma Torres, Verónica Alejandrina Romero Ramos, Victor Lovera Salazar, Yovani Alejandro Viruel Ramírez.

edición: Lucía Hinojosa

acompañamiento de traducción al cuerpo: Victoria Gutiérrez

Muchas gracias a Victoria Gutiérrez, Sebastián Gutiérrez, Rocío Cerón, Abraham Chavelas, Maryana Villanueva, Centro Cultural de España, y todo el equipo de ENCLAVE.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

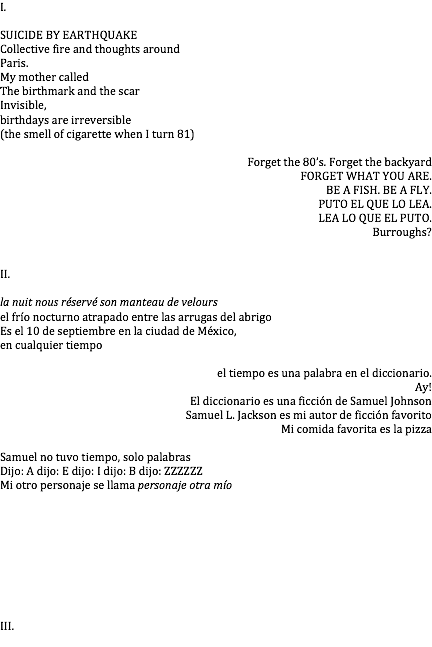

// collective poems from september 10th //

by:

Luna Montenegro, Adrian Fisher, Andrew Birk, Sira Piza, Diego Gerard, Hugo Roca, Carolina Castañeda, Lucía Hinojosa & Nico Libeyre.

0 notes

Text

EL QUINCENAL presents Neruda’s Grapes and the Wind /Las Uvas y el Viento. A translation by Michael Straus

Michael Straus lives in Mountain Brook, Alabama. Among other activities, he writes occasionally on Greek poetry and drama; is actively involved with a number of museums and other arts-related organizations; and recently completed the first English translation of Pablo Neruda’s long poem, Las Uvas y el Viento / Grapes and the Wind, a poem he first encountered as an exchange student in Santiago, Chile.

Pablo Neruda was the pen name of the Chilean poet, diplomat and politician Ricardo Reyes Basoalto (1904-73). Writing in a variety of modes including love poems and other lyrics, historical epics, political manifestos and a prose autobiography, Neruda won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971.

Excerpt from Grapes and the Wind / Las Uvas y el Viento.

Pablo Neruda ©1954

Heirs of Pablo Neruda and Fundación Pablo Neruda ©1999

Translation Michael Straus © 2017

1 note

·

View note

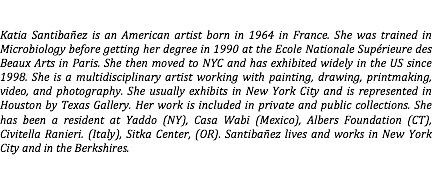

Text

EL QUINCENAL presents MURMURS OF EARTH by Christopher Rey Pérez

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

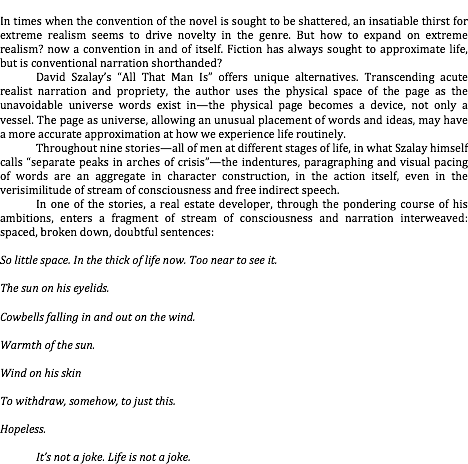

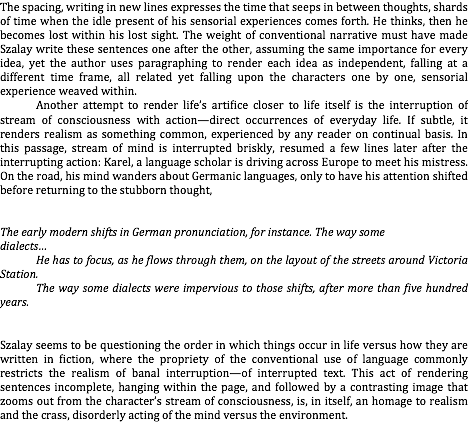

EL QUINCENAL presents a review by Vernon Sullivan

0 notes

Text

EL QUINCENAL presents FEVER by Jeanette Nevarez

0 notes

Text

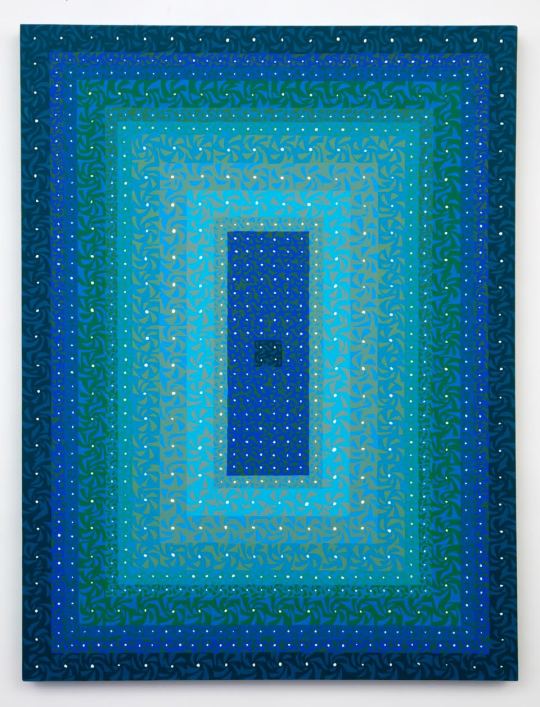

EL QUINCENAL presents FOLLOW THE BLUE GAZE by Katia Santibañez

0 notes

Text

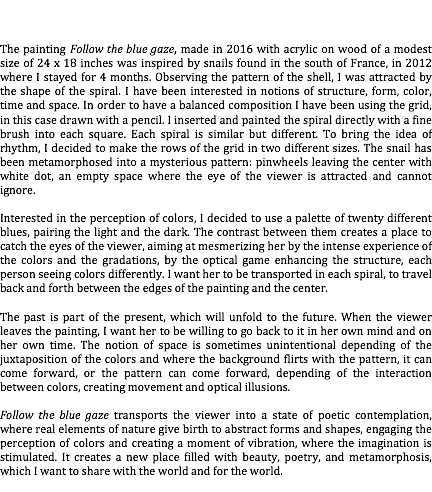

El QUINCENAL presenta BAJO TIERRA, por Mariana Galán

Mariana Galán cursó los estudios de Licenciatura en Artes Visuales de 2005 a 2014 en la ENAP, la Facultad de Artes UAEMEX y la Universidad de Sao Paulo. Como artista emergente, su práctica es un proceso reflexivo sobre preguntas de cultura e identidad.

BAJO TIERRA: Entrevista con Rufino Basurto

por Juliana Ángeles

J.A.: A pesar de que no ha causado gran revuelo, su último hallazgo en el Nevado de Toluca es interesante para la ciencia, pero también para la sociedad en general, porque nos habla de un pasado que de alguna manera es común a todos. Nos ha interesado principalmente cómo problematiza la labor interpretativa del pasado y el lugar que ocupa en nuestras vidas. ¿Qué opina usted al respecto?

R.B.: El problema con el pasado siempre ha sido desde dónde lo pensamos y cómo lo interpretamos. En un sentido muy foucaultiano, qué categoría estamos construyendo para analizarlo. Un ejemplo que me gusta colocar es el de los hermanos que tras la muerte de su padre se sientan a discutir quién era y cómo fue. Todos los hermanos tendrán versiones distintas sobre su padre dependiendo de su relación con él –dolorosas, de enojo, cómicas, etc-, recalcando cosas diferentes, incluso contradictorias, y ninguna será más verdadera que otra, pues todas son reales y han sucedido.

Por esta razón todas las personas han tenido un pasado distinto. El “hecho“, por ejemplo, de que todos tengamos un único pasado en común como en los discursos nacionalistas, tiene un uso adoctrinante y moral –los buenos y los malos de la historia- más que de conocimiento epistemológico.

La cuestión hoy en día, tras la caída de los grandes relatos que explicaban nuestra existencia, es la posibilidad de múltiples interpretaciones en torno a un mismo fenómeno, con verdades relativas sujetas a debate. Lo que trae a colación, la libertad y responsabilidad de elegir lo que pensamos y queremos ser.

J.A.: El Sol de Toluca publicó el reporte de su excavación como suplemento especial, ¿cómo fue la acogida del público toluqueño?

R.B.: Desafortunadamente no tuvo mayor relevancia, la gente no lee ni está interesada en estos temas, y en general creo que la sociedad toluqueña es aún bastante dogmática y apegada a sus instituciones, que mantienen mucho poder sobre las verdades de su identidad colectiva.

J.A.: Ha mencionado la historia oficial…¿qué relación guarda con su hallazgo?

R.B.: La historia oficial es útil como dogma, a propósito de Toluca para cierto mito fundacional de la ciudad como el de la política, que ya se ha aprendido de memoria su libreto sin que nadie cuestione la validez de lo que se recuerda y se olvida. Nuevamente percatémonos de que los hechos son valorizados, narrados, ordenados y metaforizados desde un lugar de poder. Hoy en día hay una conciencia más crítica al respecto por la carencia de fundamento de una sola historia verdadera, y nuestros destinos e identidades sociales se atomizan y reagrupan en nuevos sentidos. Nuestro lugar de poder está, en un sentido heideggariano, en la conversación que somos, más fundamental que el suelo sobre el que estamos.

Mis colegas cuestionan la validez de mis hallazgos por la manera tan simplona en que fueron descubiertos. Aseguran, irónicamente, haber pasado por los valles del Nevado muchas veces sin que se les revelaran “diminutas puntas iridiscentes“, como postulo en mi reporte. En mi defensa, puedo contestarles que yo tenía algo que ellos no: la curiosidad de hallar la grieta, la inquietud del intersticio, la voluntad de mirar dentro de las cosas abandonando la apariencia exterior, para ver otra cosa. Otra cosa, antropológica o filosóficamente que no sea Adolfo López Mateos, el chorizo verde o el Cosmovitral.

Mi hallazgo aporta algo aún indeterminado, pero no menor. Frente a algo que no conocemos, que es antiguo y estaba oculto, hace evidente la pregunta ¿qué está usted viendo aquí y por qué?, y eso me resulta más interesante que cualquier verdad concluyente sobre el mundo.

J.A.: ¿Cuál es su postura entonces sobre el origen y el lugar del pasado?

R.B.: El tema nos toca porque todos tenemos memoria, que es la forma en la que nos construimos al relatarnos a nosotros mismos nuestro tiempo existencial. El tiempo cósmico o físico y nuestro tiempo humano son dos cosas muy distintas, pues nuestras historias, cómo diría el cineasta Tarkovsky, son la forma en la que esculpimos el tiempo.

Pero ¿por qué es relevante el pasado? de alguna forma nos preocupa el origen, nos preocupa el mundo que nos antecede y por el que estamos hoy en día aquí de esta manera.

La historia del “hombre“, un concepto complejo que engloba muchas cosas, debe entenderse como el drama silencioso de sus configuraciones. Renovar la pregunta por el origen y la situación del hombre es arriesgado aunque importante.

Con la apertura de otras explicaciones ontológicas como la científica, a la par de la teológica-metafísica-sagrada, el hecho humano ya no se busca arriba en lo divino, sino “abajo“ en la tierra, en los factores tangibles. Lo sólido, más que algo que realmente posean los objetos, es una propiedad atribuida psíquicamente a lo inalterable, a una especie de verdad dura en la que sustentar nuestro origen descendente. A pesar de que la arqueología me parece de las ciencias más imperfectas porque la distancia entre los hallazgos y la interpretación es máxima, el “bajo tierra“ nos sugiere nuevas imágenes sobre nuestro tiempo existencial. Imágenes de la profundidad, lejos de los cuerpos diáfanos que nos constituían.

A mi modo de ver nuestra relación con lo oculto bajo tierra es una relación isomórfica, en la que la tierra nos revela nuestra propia profundidad. El carácter secreto de la materia no es un secreto que se conoce, sino un secreto esencial que se busca y se presiente. Cada quien escava y encuentra sus tesoros particulares.

La complejidad de esta excavación –y de todas quizás- es la dificultad de suponer a un “hombre“ previo para llegar al resultado predeterminado de nuestra actualidad, decir que nuestros antepasados hicieron tal o cual cosa por la que hoy día estamos aquí. ¿Qué prueba esto? ¿que nuestra cultura es antigua? ¿que llegamos primero y por ello este territorio nos pertenece? ¿que no hemos cambiado en siglos? ¿dónde empieza y termina el nosotros?

Suponer al mismo “hombre“ desde el pasado, fingidamente derivado de modo evolucionista, niega nuestra historia-en-el-mundo, dado que no nacemos hombres, sino que llegamos a serlo. El hombre en su existir no es un producto pasivo del ambiente, sino un formador de mundo.

Desde las posturas más radicales, pensadores como Jacques Derridá piensan que no se puede obtener ningún conocimiento del pasado pues siempre nos enfrentamos a una realidad que es nueva y cambiante. Lejos de ser especialista, yo pienso que la conciencia histórica es importante mientras nos despierte reflexión sobre nuestra temporalidad mudable y limitada: la consciencia de que convivimos en un universo simbólico donde todo lo que decimos y hacemos flota sobre un horizonte de provisionalidad.

Esto quiere decir que a pesar de nuestra herencia, biológica y cultural, siempre está latente la posibilidad de amoldar nuestro presente. Así como se esculpe el tiempo, me esculpo a sí mismo en el éxtasis de mi presente, que es el único punto que realmente me pertenece.

J.A.: Hay un fragmento en el que coloca el papel de la imaginación en la construcción de verdades científicas, ¿puede hablar más al respecto?

R.B.: Hay distintas naturalezas de conocimiento, pero pienso que en nuestro mundo ampliamente tecnocratizado se olvida nuestra relación fundamental con el mundo: se habla mejor de una realidad líquida que se ha empezado por soñar, antes que un dogma. Por soñar me refiero a algo que no se ha logrado aprehender en su totalidad, y que se completa en el sesgo de lo desconocido. La imaginación nos lleva de la introversión a la extroversión, de ser ajenos a los objetos a poseerlos en su intimidad. D.H. Lawrence una vez dijo que vivimos en el reverso del mundo, en nuestra negritud profunda.

Para fines del presente, el bajo tierra provoca una metáfora con mucha riqueza en profundidad e intensidad. Asumimos que es el pasado lo que brota cuando escavamos, asumimos que es intocable y lejano, sin percatarnos del bucle en el tiempo que es nuestra presencia en esa excavación. Si el pasado permanece como resto y como lugar conceptual, todo hallazgo tiene algo de sesgo y ficción, una construcción sobre su tiempo y espacio, que no debe entenderse como una cualidad negativa. La ficción es la reconstrucción de un fenómeno, que no es el fenómeno mismo, y por ello creo que podemos ver al pasado-presente como un movimiento de mareas continuo. Escribir y relatar es inventarse y al inventarse descubrirse, dijo alguna vez Octavio Paz. La indagación sobre el hombre y su posibilitación histórica debe girar en círculo de tal manera que volvamos al punto de partida –nuestro acontecer, nuestro tiempo, nuestro éxtasis existencial- y nunca lo abandonemos.

La conciencia de que las convicciones más profundas que uno tiene son el resultado de un giro poético y creador del pasado, de una conversación con otros, sin un punto de creación único.

J.A.: Por último, ¿qué no puede decir sobre la exposición itinerante de su colección geológica “16 rocas improbables“?

R.B.: Mi objeto favorito en el mundo son las piedras, porque como nuestro pasado, son condensaciones de múltiples movimientos terrestres que nos constituyen.

Esta colección ha sido recolectada en viajes, principalmente de encuentros afortunados, y algunas piezas incluso obtenidas como obsequios. Como usted sabe, la labor de clasificación ya nos dice algo sobre esta colección. Su categoría tiende más a la razón creadora radical y exploradora por su constitución imprecisa. Las piezas me llevan a pensar de la mano de Peter Sloterdijk que en realidad venimos de las piedras y no del mono: fantasmas de piedras, piedras monstruosas, fósiles de fósiles calcinados por volcanes, masticados por erosiones, glaciaciones, guerras e impactos de meteoritos. Son el vomitivo producto de la historia, sin un punto de creación único.

Aunque para darle a usted la sospecha de qué pensar, finalmente una piedra es una piedra, lanzarlas es nuestra apertura hacia un horizonte lejano.

0 notes

Text

EL QUINCENAL presenta: IMPERIAL BEACH, Marcia Santos

Marcia Santos (Cd. Juárez, 1990.) es Co-Fundadora del colectivo curatorial de red de agentes de arte contemporáneo "Toperweb. Concluyó la Licenciatura en Diseño Gráfico, y en la actualidad cursa la Licenciatura de Teoría y Crítica del Arte en la Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, asÍ mismo, es estudiante del Programa Educativo SOMA.

Ha exhibido en la III Bienal fronteriza en Cd. Juárez y El Paso, Texas en 2013; II Bienal Nacional e Internacional 2013 de Arte “Desde Aquí” en Colombia; Becaria en el programa de jóvenes creadores “David Alfaro Siqueiros” en I.CHI.CULT. 2013; en el Laboratorio de Arte en La Quiñonera, 2013 en D.F.; Desarrolló una Residencia Internacional de investigación en Arte Contemporáneo con el grupo de Curatoria Forense en Uruguay, 2014; Ha participado en la Bienal Nacional “Artemergente” 2015, Monterrey. Colaboró en el proyecto editorial "Arte contemporáneo en México, gestión participativa y redes sociales" de GPNC, 2015-2016. Actualmente colabora en Project Space Festival Juárez 2016.

IMPERIAL BEACH

Caminábamos por las playas de San Diego, y to be honest, i hated him.

Me resultaba patético su existir.

Panza redonda de miedo, transparent yellow skin, arrugada, llena de lunares, ¿Estaba allí para llenarme de qué?

Pedí el breakfast más caro del restaurant—como venganza.

Bacon Hamburger.

Comí pensando en cualquier cosa, ignoring the smiley shadow beside me, desdeñando lo que había acontecido esa mañana.

Yo era la nice hooker, morena, mexa, pobre, veinteañera, broken english.

Pasamos un monumento que para mi significaba la conquista del petróleo en el mundo: juegos de plástico y goma moldeable para los niños que visitaban la veteran beach. Beautiful place que les habían otorgado a cambio de muertes de guerras anteriores.

-This rubber used to make these games is super toxic but nobody says anything, children play anyways.

Tocando la arena con los pies me confesó:

In war everybody gets sick.

Some time ago I was on a mission in an African country. I was asked to hunt down a group of slavers who kidnapped civilians and sold them to transnational corporations for forced labor.

We were on the trail through northern Africa, almost snapping at tracks, until one day we caught them near the beach.

We tortured them.

Then a machine dug many holes in the sand, the depth of a body up to the neck.

We buried them.

And another machine stepped over them and cut off their heads.

Several of my colleagues grabbed decapitated heads from the hair and took selfies.

War ill.

Sound of waves, gaviotas y la gente laughing a nuestro alrededor aderezaba la narración, suddenly I saw a child contemplating his own childhood.

Por un instante sentí un amargor que emanaba de algún lugar que no era físico.

Emboscada, castigada, vigilada.

I was there, con la brisa salada pegada a la skin, judging me like the hardest weapon.

¿En qué momento decidí ser my propio victimario?

1 note

·

View note

Text

EL QUINCENAL presents: Down South by Kyle Proehl

diSONARE Magazine is pleased to announce a new series of online publications. We will feature short fiction, poems, and creative essays in English and Spanish. Pieces will be published twice a month. The first piece is “Down South” by Kyle Proehl.

Kyle Proehl is Senior Editor at Art Handler. He has written for Dispatches and Les Presses Editables.

*****

I finally got rid of my phone. Rachel left just after that. She couldn’t take it, not knowing. Not not knowing where I was, but if I’d ever be the kind of guy to have a phone again. What that meant. The kind of guy with the kind of job that meant the kind of investment, such as a phone, that would help us grow together. Not the kind of guy who took getting laid off as a sign. Or the kind of sign I took it as. She left our little bungalow and went back to her parents’ house. They had two houses, her parents, and she went to the one where they weren’t. Left me with sandy floors and a painful rent, as if to remind me of all I couldn’t do on my own.

So I thought about leaving too. Or the dreams I used to have returned in my new freedom. I thought about it a lot on the beach, in the water, at the bars, pretty much wherever. The emptiness of the bookshelves and cupboards and kitchen echoed in my head. Hope wasn’t for us, that was the truth. Rent was cheaper down south, I could still live by the beach, my severance would run out eventually and I’d be forced to get a job that meant nothing, which sounded just about right. She’d never see the point. That was okay, I would live, but I’d probably be living alone for a while.

The bars of the beach welcomed me back. The Neon Blue especially. That cool blue light, just like it says, the bar’s ridiculous wave, greyhounds that glow in the dark, day and time told purely by crowd. We’d mostly stopped going, so when I returned the word got round. I took advantage, wallowed, indulged. Made sure however to refuse what might have taken me too far from that moment. This was moving forward, I thought, waking up on a stranger’s couch wearing a single crusted sock. It wasn’t the life, but neither was respectability. I was looking to refuse it all.

Not many people found my Mexico plan too attractive, not with the recent hostilities. The army had moved in to Tijuana just before Rachel left. Like a ghost town, the bartender said, it’s not even cool to visit. I hadn’t been in months, and the warning got me thinking. Maybe I couldn’t move right away, but I could do some reconnaissance. Rents were sure to go down if people kept turning up dead, and it seemed they were just getting started.

Walker still lived down there, still commuted to the paper during the week, still took tourists off the beaten track into the real TJ a couple of weekends a month. He was from Iowa. Still working up the nerve, like everyone else, to leave the paper for good. I sent him an email, I didn’t want a tour, couldn’t bring a group, Rachel was taking all our friends, or I was giving them away, him too maybe, maybe it was too late, I didn’t mention all this, but some of it probably made its way in somehow. Walker wrote back anyway, right away, I was welcome anytime, just let him know, he had a sofa, we’d eat and drink and dance and eat again and forget to sleep. I fired back, why not tonight, I felt like it anyway, though I’m not sure I did, what did it matter, only I had no phone, so we’d have to make plans or something, choose a time and a place. He replied, it was one of those days, how about Rasputina at ten, I’d been there, had no idea why it was called that, no one did, or no one remembered when they were told. The plan felt a bit reckless, maybe normal to Walker, except for including me, maybe I should bring a friend, or maybe he would, so we could avoid a plunge into the obvious.

I spent the rest of the afternoon reading up on all the violence. To prepare for the worst, give the trip a moral edge, feed an obsession, who knew. Walker’s website avoided the whole situation, he’d been fed up with the negative view even before packing his bags for the border. There was so much more than what we thought we saw. Before he was the tour guide he was still becoming he was just a guy who wanted to take his friends into every corner of his new city. Brighten the shadows, break up the clichés. Mostly by drinking at different bars, shopping on other streets, buying tickets to odd events. In a word, avoiding Revolución. Even with the rumors and news, there was still so much to do. The only headless bodies they’d found so far were narcos or police. The food was still terrific.

It was a Tuesday. Either that actually mattered, or people were actually scared, but no one wanted to join. This girl at the Blue said she was down, then made that face and tottered off to the bathroom, which is when I paid and left.

The night was warm, the drive went smooth, south of downtown the highway darkened, emptying itself right to the end. When I pulled off the last exit, there was one set of red lights ahead, one pair of white behind. Plenty of spaces in the lot, the lonely walk through the empty middle, bored drivers and their yellow cars, hardly a soul to honk at on the streets. Only after I was in a taxi did I wonder what makes a target, what made it clear I had nothing to offer, I wasn’t worried, just curious about my appearance, what made it disappointing. We didn’t talk much, me and the driver. Business was bad, the Americans were scared, the streets were quiet, isn’t everyone. Perched at the edge of a drift, a melancholy goodbye. On the curb I realized I’d never watched a cab I’d just left drive off into the night.

Rasputina was deserted. I stood in the doorway waiting for memories of better times to rush in, I must have seen it like this before, but nothing came, the chairs, tables, stools didn’t welcome me, the walls and the light were too bare, but it was too late, the bartender had spoken. I took a stool and asked for a beer and a tequila. And watched the room in the mirror and waited. Flipping through a magazine, maybe bothered by my silence, the bartender said there’s a jukebox. Lots of gringo music. That wasn’t all. I picked a few corridos with heroic titles. She looked at me without smiling, kept flipping pages, expecting no one.

Wonderful time to shut it down, said the man to my left. He had a beer. What happened to the time? He spoke English. We should get an award. The bar was still empty. He wasn’t looking at me, at anything really. I had a beer, but the tequila was gone. Do you know what a newspaper is? he said. I didn’t answer. He waited. The perfect lining for any animal’s cage. Which paper do you work for? I said. The same one you used to, he said, looking at me, then back into space, but it doesn’t matter, they’re all the same. I’ve seen you in the newsroom, once or twice when they called me up to check on my discipline, my sanity, loyalty. Whenever the leash fraying across the fence snapped and they had to fit me with a new one. More than a few angry oars on this stinking ship. I have read you, this is what happens. The curdle of mundane disgust. Shame you arrived for the backslapping triumph. Malcontents need a new refuge. This bar has never been so empty. Not even when it was closed. And they shut down my desk. Bigger insult than getting fired, believe me. No leash needed if you chop off the legs. You know where they’re trying to send me? Escondido, the new destination for patrons of the arts. Gallery district looked suspiciously like a row of antique stores, but what do I know. Trying to get me to quit without severance. And they probably will. No guts left. That’s why it’s just you and me here. And I don’t even know why you came. The world tears itself apart and we hide our faces in money. Dos Zapatistas, por favor. Can you believe they gave a mezcal this name? But it’s the only one here, so it’s not like we have much choice. To reckless humanity.

It didn’t even burn. He was Lorenzo, by the way, Lorenzo Clark. I knew the name. Another filthy gringo conquistador returning to comfort and safety. I was just waiting for a friend.

The Tribunal was closing its Tijuana bureau in two weeks. They just got word that afternoon. Rumors for months, not a straight answer to be found, then two weeks left. Only a staff of three down here anyway, so really a symbolic office, except when it wasn’t, which could always happen, because we were here. Resonant in contradiction, but bearing witness nonetheless. Now just reinforcing the wall. It’s not a fence, take a look. The infuriating thing is to spend years cultivating cynicism and have it fail you. Expected, unavoidable and still. There’s always something else.

This was not the night I was hoping for. Walker had failed already. It would take maybe more than I was prepared for to wipe this away. He knew how, I was sure, but Lorenzo’s words raised my doubts. I had forgotten that bitten-tongue taste, or thought I could, but here it was again, sunk and spread with the mezcal heat. Like lava it worked through my veins, raising hairs like cast steam, searing through days past I thought I was still living, becoming memory only then, only in that burn, my life a flaming ruin, which I tried to douse with beer. Faces slanting through rooms and streets in this city becoming dust, hardening to fossil behind the smoke, the redness rolling slow out toward the edges like a setting sun. Slow and inexorable, a creeping blindness, forgetting itself. What remained I could sift through, inhale the aroma, but what vanished would return as the only thing worth facing.

That’s where Walker found me. Couldn’t believe the state of the bar. He knew Lorenzo, we had another mezcal, grand idea, said good night, Lorenzo was committed to shutting it down, if no one else was, and no one was, so we left.

The rest of the night hardly happened. Walker had friends, we met them at a club, everybody’s hands held giant bottles of beer, upstairs over an empty street, the evacuating city, taking its time. It was too loud to talk, too something, there was only dancing with your eyes closed or throwing yourself over the balcony toward a silent doorway, which is where I was when we decided to leave, so much we didn’t get to, that night or ever. Another time, soon of course, it’s been too long besides. And in the cab back to the border, no worries, not even the fare. The driver made no attempt. I hope it gets better soon, he said.

1 note

·

View note

Text

La Guerrilla Anti-Trump de la Editorial Badlands Unlimited

BADLANDS UNLIMITED

La nueva campaña de la editorial Badlands Unlimited, fundada por el artista y escritor Paul Chan, tiene como eje central frenar la xenofobia actualmente presente en Estados Unidos. El gran villano de la narrativa es el empresario billonario y candidato republicano a la presidencia Donald Trump.

Para promocionar su colección de verano—libros de artista en formato digital—Badlands Unlimited ha creado un poster en español para ser distribuido durante el verano en Nueva York, Brooklyn y Queens, al estilo guerrilla. Bajo el slogan “Que se joda Trump y sus amigos racistas,” se dan a conocer los libros Transformers de Howie Chen, How Many Am I Now? de Amy Lien y Enzo Camacho, Working the No Work de Georgia Sagri, Dynasty de Bernhard Willhelm, Decrophilia de Matthew Raviotta, The Nothing Pitch editado por Magnus Schaefer y The Sandy Cat de Rachel Rose. Los escritores trabajan en medios como la moda, estudios curatoriales y arte contemporáneo, tratando temas desde la vida cotidiana hasta Wall Street, libros para niños, hogares suburbanos y fantasmas.

Adicionalmente, la comunicación en redes sociales de Badlands Unlimited ha sido en español durante todo el verano, con el objetivo de frenar la retórica racista del partido republicano y su líder, y para insultarlos en un idioma alterno.

Una de las declaraciones centrales de Badlands Unlimited como editorial es que “la distinción entre libros, archivos y obras de arte se encuentra en estado de disolución,” misma que los ha llevado a producir libros de contenido y discursos muy variados, desde una línea de ficción erótica, hasta re-ediciones de diálogos Platónicos. Con esta campaña, Badlands Unlimited expande el impacto de sus publicaciones, incursionando incluso en posicionamientos políticos y sociales, de cara a la elección presidencial venidera.

-diSONARE Magazine

0 notes

Video

el caminante huye del ruido

No será sorpresivo abandonar a la palabra entre las pantallas de un mundo inquieto por sus movimientos.

La retirada de la página es la treta que a los poetas avisa del tiempo bélico: los estímulos sintéticos, las señales producidas sin ensueño, alertarán al devenir poético tornándolo concreto si es de la materia inerte su permanencia volumétrica; amago si es de la insuficiencia sensible arrojarse a la batalla; resguardo si es de la voluntad pequeña el miedo. Mejor que peor, habremos de acomodar algunas frases junto a las imágenes que median su movimiento, con el esmero caduco de autonomía. Porque las palabras en pantalla no funden en sus desviaciones las miradas, no yerran su sentido del todo percibido ni del equívoco momento, buscan maridaje en las traslaciones de otros cuerpos, prevenidas del poderío moderno de la imagen. Se han desplazado dando guerra en el vacío de la secuencia, sobre el incierto espacio negro al que su grafía estaba expuesto, trastocando su privilegio místico por una ilusión de movimiento que consume y transforma al pensamiento, creando espacios indeterminados para el escape, el hundimiento o el poema; este engaño prevé al poeta de dar guerra y situarse en otro campo que no le exige su proeza, la del caminante en la periferia.

D. O. S.

2016

0 notes

Text

diSONARE at Chalton Gallery in London, UK

Last April 30th diSONARE 05 was presented at Chalton Gallery, alongside a sound piece by artist Laura Cooper, using recorded readings by artists and writers of previous issues.

Cooper’s piece, Mouth to Ear is a meditation on how we listen through headphones in a confined gallery space when confronted by audio content. The listener becomes the performer while Cooper’s voice directs his or her behavior throughout the gallery space, preparing the listener for new voices and content, which will be heard through the headphones. At the same time, the piece offers an anthological perspective of the magazine’s five issues up to date. Mouth to Ear is presented through two audio channels with different collaborations.

Chalton Gallery, led by Mexican curator Javier Calderón is a space showcasing Mexican and British Exhibitions, devoted to an international public program of moving image, performance, talks and experimental sound and music. Also, the gallery is creating a library with a unique collection of publications and videos of Mexican art.

diSONARE Magazine thanks Chalton Gallery, Javier Calderón, Laura Cooper, Helena Lugo, Sofia Casarín, and the contributors who participated with recorded readings.

________________________________________________________________

El pasado 30 de abril diSONARE presentó su quinto número en Chalton Gallery, junto a una pieza sonora de la artista Laura Cooper, utilizando lecturas grabadas por artistas y escritores de números previos.

Mouth to Ear de Laura Cooper es una meditación sobre cómo escuchamos a través de audífonos en el espacio limitado de una galería. El oyente se convierte en el performer mientras la voz de Cooper manipula su comportamiento dentro de la galería, preparándolo para escuchar más voces y contenido a través de los audífonos. Al mismo tiempo, la pieza ofrece una perspectiva a modo de antología de los cinco números de la revista.

Chalton Gallery es un espacio que muestra arte mexicano y británico, dirigido por el curador mexicano Javier Calderón. También, la galería está creando una biblioteca con una colección particular de publicaciones y videos de arte mexicano.

diSONARE agradece a Chalton Gallery, Javier Calderón, Laura Cooper, Helena Lugo, Sofía Casarín, y a los artistas y escritores contribuyentes.

0 notes

Text

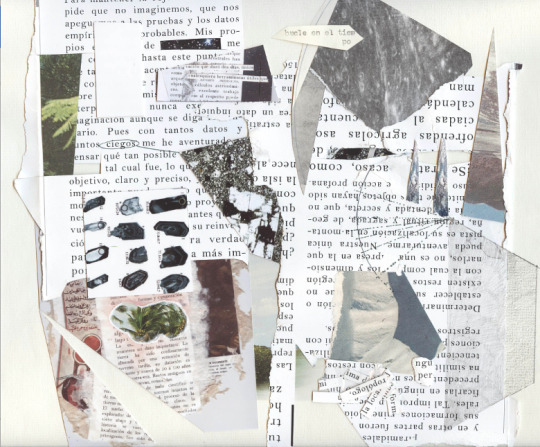

diSONARE with Chris Sharp

Chris Sharp is a writer and independent curator based in Mexico City where he co-runs, with the artist Martin Soto Climent, the project space Lulu.

diSONARE’s editor, Diego Gerard met up with Sharp at Lulu to discuss themes like the figure of the curator, the role of independent project spaces, and the similarities between the language of contemporary art and the language of fiction. Sharp’s story Natural’s Not in It has been recently published in diSONARE 05.

Diego Gerard: What are your thoughts on independent curatorial practices in Mexico City?

Chris Sharp: Having lived here only a short time, I’m not sure if I am really qualified to talk about it. I can speak about Europe and the US, where I have spent much more time and where the (independent) curator is much more defined. In Europe for instance, the curator is much more respected as an auteur, or a co-producer of meaning, narrative, and experimental frameworks, which are encouraged and embraced in exhibition making. In the US, the curator, and curatorial practices, are generally much more academic and institutional or yoked to the market, which is reflected in rather one-dimensional exhibition concepts like “new photography” or “new painting.” I get the sense here, in Mexico City, as elsewhere in Latin America, the (independent) curator is often linked to the idea of research. I know a number of curators who add the term ‘researcher’ to their title. I have mixed feelings about this (quite frankly, I find the ubiquity of this term in contemporary art very problematic). On the one hand, it strikes me as a pleonasm, which has a way of negatively nuancing the practice of curating with a certain scientific capacity, as if art were subject to the same quantitative methods of inquiry as a science or sociology. And on the other, I can’t help but respect the impulse from which it arises, which is about filling in a lot of historical lacunae, which is the mission of the interdisciplinary research platform Red Conceptualismo del Sur. But whether the independent curator even exists is debatable. A friend and colleague of mine, the Berlin-based Austrian curator Christian Kobald once told me that he believed it to be a kind of mythical beast. According to him, all independent curators were just unemployed, on the look out for a job, stoically enduring their status the way a handicap endures their infirmity. Part of me is inclined to agree with him, and another part is less sure. I know a number of independent curators, such as the Lithuanian Raimundas Malasauskas and, say, the American, New York-based Robert Nickas, not to mention Christian himself, who seem to have selected their unmoored status. I myself have never had a job in an institution, and although in the ten years that I have been peddling my services as a mythical creature, I have applied for three positions (none of which I got), I’m quite happy to remain the monster of myth Christian makes us out to be. But then again, maybe I am just unemployable? Probably.

DG: I believe there are few galleries such as Lulu, which independently curate without representing artists, or being interested more specifically in the market?

CS: Well, first of all, we’re not a gallery. We’re a project space, or an independent space. I say that because as you rightly point out, we do not represent artists. We have no roster, nor do we intend to. For the moment, we are, largely by necessity, a hybrid space which (occasionally, or very rarely) sells work in order to sustain itself. In the sense we are like P! in New York, or maybe more like Castillo/Corrales in Paris, which unfortunately recently closed, or maybe even a bit like White Columns in New York, which is a bona fide non profit that sells art. But Lulu is a very curatorial project, whose program can even be seen as a long term, linear exhibition.

DG: Do you think there’s a lack of dialogue, influence or critique between the contemporary literary scene and the art scene?

CS: It seems like it could be stronger, but it also depends on who you’re talking to and where you are. Platforms such as Bomb magazine or different publishing houses (Semiotext(e)) for instance advocate for a very active dialogue between the two. Even though you have great writers in the US like Chris Kraus, Eileen Myles, Ben Lerner and Ariana Reines who are very involved in contemporary art and writers like Tom McCarthy in London, the propinquity of the two seems more conspicuous in Mexico. I remember being very impressed when at the cantina Covadonga in Mexico City one night and seeing artists like Gabriel Orozco and writers like Guillermo Fadanelli, Francisco Goldman, Gabriela Jauregui and Alvaro Uribe all under the same roof (Valeria Luiselli could have been there as well, and maybe she was?). It felt, at least superficially, like the halcyon age of the European avant-garde, when the two disciplines were much more linked– e.g., when a movement could be both literary and artistic. I think it’s also interesting that you have a literary critic like Rafael Lemus co-organizing this year’s edition of SITAC in Mexico City. This feels somehow significant and yet perfectly natural here.

DG: As an independent curator and critical writer, how do these practices affect or dialogue with your interest in fiction?

CS: They do so more and more. Having originally studied literature and not art history, virtually, at all, I used to feel deficient and embarrassed by this lack of formal education, always playing catch up, reading, looking, doing my best not to look vacant and lost when I had no idea what people were talking about, learning on the job. But over the past few years, I have begun to realize that my literary education was more of an asset than a deficiency. Against a backdrop of increasingly standardized art education and streamlined professionalization, I think my unconventional background might not only give me an edge, but also help make a dent in ensuring that the field doesn’t become too homogenous. But then again, maybe my education is not so unconventional. Some of my colleagues whom I admire the most, such as the French, Paris-based curator François Piron, also have similarly unconventional art educations– in François’ case, also literature– and it works very much to their advantage.

In practical terms, I guess I would say that my relationship to literature comes out in the perception and construction of an exhibition as a kind of open spatial narrative, in which art objects take on an almost syntactical texture and dynamic, especially vis-à-vis one another. This is not say that I necessarily impose a strict, narrative structure upon whatever art I am showing, but that each work’s relation to others is always paramount and that space, like a stanza break or the white space of the page, always plays a crucial role in the physical composition of any exhibition. Whenever Harald Szeemann was very excited about an exhibition or grouping of works, he would characterize it as “sheer poetry,” and in many ways that is what I am going for.

As far the theoretical side of things go, I have been thinking a lot more in terms of compassion lately. This is something that has really played out in a series of exhibitions I curated in 2014 and 2015 in Europe entitled “The Registry of Promise”, and in Lulu here in Mexico City (I mean given Lulu’s size and its emphasis on the intimacy of the viewing experience, it has a way of meeting any viewer half way, all but whispering if not into their ears, then into their eyes). This comes from a multitude of sources, but probably most specifically from Virginia Woolf, namely, “To The Lighthouse” (1927), which for me, is the compassionate novel par excellence, and the short stories of Donald Barthelme, not to mention certain works by Beckett, like the one-act play “Krapp’s Last Tape,” (1958) which is a tiny colossus of heart break, or certain passages of Flaubert, Céline and Proust. It is from the likes of them that I take an interest and belief in an art that seeks to understand as opposed to condemn. This is not to say that I reject so-called criticality in art; compassion does not preclude criticality. But any art that does not privilege compassion, does not evince a palpable minimum of emotional intelligence and dismisses the complexity of the human animal ultimately fails to take into consideration the complexity and intelligence of its viewer and, as a consequence, is most likely destined to fail as art (curiously, Nabokov’s seemingly reductive equation/definition of art starts to make more sense to me: “Art,” he was fond of saying, “is beauty plus pity.”)

DG: Does the language of fiction have anything in common with the language of contemporary visual art?

CS: In my personal universe it does. One of the most influential revelations for me over the past couple of years has been the work of the American novelist Ben Marcus, in particular “The Flame Alphabet” (2012) and “Notable American Women” (2002). Such strange, textured and plastic language! Rarely have I encountered such a sensuous relationship with the written word. Marcus produces, nay secretes a writing, an almost erotic syntax, which, like great painting, has a way of rubbing against your body, both on the outside and inside. His work is one of the better recent arguments I have encountered not only for the total indivisibility of form and content, but also for the necessity of formal innovation. As in many ways, he is a formalist– but a formalist in the richest sense of the term. One that believes that the life force, the vitality of a given art form depends on being formally pushed to its breaking point, which often touches upon non-sense, and which is the precise locus of a given writer or artist’s truth. And perhaps more importantly, he believes in the autonomy of words, the materiality of words, of words as things replete with a vast spectrum of formal qualities in and of themselves. He has a way of both dignifying and doing a great violence to language and syntax (all great formal innovators are violators, are prodigies of brutality, I believe. Céline, in French, is one of the best examples of this; the violence to which he virtuosically subjects the French language scorches it to life).

What I am trying to express here is probably better, and more simply expressed by a passage from the American poet James Schuyler’s “The Morning of the Poem” (1980). He writes:

So many lousy poets

So few good ones

What’s the problem?

No innate love of

Words, no sense of

How things are said

Is in the words, how

The words are themselves

The thing said: love,

Mistake, promise, auto

Crack-up, color, petal,

The color in the petal

Is merely light

And that’s refraction:

A word, that’s the poem.

For exhibition making, please replace poets with curators, and words with art; and for artists, please replace poets with artists and words with materials.

Any artist or writer who seeks to smuggle content into form always gets caught, as if one came after the other. They don’t understand that content happens at the same time as form, through form. The same exact principle applies to (bad) curating.

DG: Is there any connection between the way we (readers) experience fiction and the way we (spectators) experience visual art?

CS: Despite the very different relationship they are liable to have with time, yes and no. At our worst, we want both to function like rebuses, to solve them like puzzles, and at our best, and depending on what we’re reading and looking at, we respect the minor miracles of creation they actually are, accepting their essential mystery. Language or no language.

Painting by Patricia Treib

The Clear and the Obscure

Michael Berryhill, Ryan Nord Kitchen, Victoria Roth, Patricia Treib

9/4 – 5/6, 2016

DG: What is the goal with Lulu, what kind of art is worth showing?

CS: I have recently been reading Philip Guston’s “Collected Writings, Lectures and Conversations” (2010) and one of the things that is sticking with me the most is how often he uses the word miracle to describe art (Guston by the way is for me a fully integrated and compassionate artist– his hideous parade of grotesques is consistently depicted with as much humor as they are with disgust and pity). Despite the religious connotation, I do believe that art can have that effect, that great art, and a great exhibition feels like a miracle, like this thing that comes out of nowhere and supersedes your understanding, literally blowing your mind. They give you so much you don’t know what do with it. By the same token, the dullest and most punishing exhibitions tend to do the exact opposite; often assuming a pedagogical armature, they tediously subject a viewer to a massive surfeit of information, speaking down to him/her from a position of academic authority while simultaneously obliging art to function as a symptom, and reducing it to so much information itself. In this scenario, I often leave an exhibition feeling attenuated, exhausted, taken from (but then again, that’s bad curating– it always makes you feel burned, diminishing both you and the art it presents), whereas the encounter with a miracle leaves me feeling charged, alive, added to, enriched. Incidentally, in temporal terms, the miracle belongs more to the future than to the present. That is precisely why it ‘blows your mind’ and enriches you– your understanding of it will come later, over time, in the future, and whatever it gives you will be spent later in coming to grasp it, however imperfectly.

In any event, as corny as it may sound and at the risk of marginalizing our work in a retrograde (il)logic of ‘genius,’ I think that’s what we’re trying to do at Lulu– make miracles happen. And when I say this, I mean in a logistical sense and an aesthetic sense. To get somebody like Manfred Pernice to come produce an entire exhibition for a space like Lulu is something of a logistical miracle, and I think the exhibition he produced for us was a minor miracle in itself. Like all the work we show, there is no gap between form and content in what he does. Manfred is a great plastic thinker. His relationship to his materials, and the formal language he elaborates with them is exemplary. As far as I am concerned, he treats particle board the same way Ben Marcus treats words; theirs is a politics of form, of materiality.

I would like people to come to Lulu and encounter exhibitions that challenge their understanding of art, of what art is and can be, obliging them to search for a new vocabulary to describe their experience. For what we do, the kind of art we’re presenting is not so easily codified into language– any art which is already fails as art; the art historian and founding director of the MoMA, Alfred Barr once characterized art, “as the most beautiful secret language we have.” Art, great art is indeed a secret language which does not so easily offer up its contents and must be learned from artist to artist, and exhibition to exhibition. In this sense, it, like John Ashbery’s description of night, “the reserved, the reticent, gives more than it takes.”

Painting by Michael Berryhill

The Clear and the Obscure

Michael Berryhill, Ryan Nord Kitchen, Victoria Roth, Patricia Treib

9/4 – 5/6, 2016

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

diSONARE interviews Mexico City Lit co-founder, writer, and journalist Tim MacGabhann

Tim MacGabhann writes across different genres. Spanning from classical poet to novelist and journalist, he is interested in the complex, multiform writing forms arrived at when combining the genres he works in. He edits the literary magazine and press Mexico City Lit. His fiction, non-fiction, and poetry has appeared in Entropy, gorse, 3am, and The Stinging Fly. diSONARE’s editor Diego Gerard sat down with MacGabhann in Mexico City to discuss the ever-changing concept of originality in writing.

DG: Can you offer a progressive definition for originality in writing?

TM: Creativity is fundamentally a critical act. You’re taking materials around you, materials that came before you, so your arrival at new combinations through originality has actually more in common with remixing or criticism rather than creativity out of nothing. One of my big concerns is the combination of genres because I work across three at the moment: poetry, fiction and nonfiction, and the latter is how I make a living, so in my own work —the artistic, non-professional stuff— I try to push myself into new territories by combining the best of what I know about those three genres. So, I suppose that originality is nothing more than rearranging and remixing to make something feel new. This is where my love for musicians like Moodymann and Monocle and J. Dilla comes in, where there is literally nothing new happening —in terms of progressions, if you want to be all Theodor Adorno about it, but also in terms of the fact that most of what’s happening is a sample— but the way it comes out gives you this delicious shiver.

DG: So you would say that originality lies in a genre hybrid per se?

TM: Yes, that’s definitely what’s influencing my riff on originality. Belatedness is a fashionable feeling, but it truly does feel like every genre at this point has had its golden moment and is falling into decadence. On my own bookshelf, I have all my best-ofs, you know: narrative nonfiction from the 60’s and 70’s, like Michael Herr and Joan Didion and Renata Adler; and then I’ve got my New York School people and the Movement people and the Rosemary Tonks types, who’ve got that shredded post-Eliot feeling; and then these massive, overambitious modern and postmodern novels whose entire point appears to be to fall into decadence — Dos Passos or Elias Canetti or Virginia Woolf, sometimes, when she does things like Orlando. So, like, what I have there is stuff salvaged from the big shipwreck of it all —and I project my own disastrous fucking time leaving Ireland onto that, to be honest— and I’m just there polishing the fragments of insight I pull out of them, or whatever. I don’t know, I’m obsessed with shipwrecks. I’m also obsessed with the time read David Shields’ Reality Hunger two years ago, even though about 70% of that memory gets my back up. He’s there talking about mixing a literary work together, as if they were all these stacked audio tracks, and then he talks about how that’s all consciousness is, and I like that even though it freaks me out something rotten. But the final point is that all you do is produce something cool, formally, because content-wise there is nothing you have lived that is unique or interesting, really, in the grand scheme of things, and there is not much you can do about that.

DG: And less so plot…

TM: Less so plot, yes. Demanding a plot satisfaction is unfair. It’s like going to hang out with your mate and being like ‘What am I getting out of this interaction?’ — when really it’s enough just to be there, in a particular place, with a voice coming at you that’s beguiling to be around. The one thing I’ve learnt as a journalist is that anything is newsworthy if you know how to tell it properly. I’m not being a sophist here: I have covered stories whose relevance I’ve had to argue for, because I believe they deserve to be heard. It’s like the opposite of a sophist, to be honest: the fact that you start from a position where nobody gives a fuck what you’re going to write about, so you have to argue them into believing that it does by the way you formally shape the thing. So if you think of literature as the news that never makes the news then anything can be literary as well if you treat it correctly. You don’t necessarily need the most gripping story in the world or the most gripping hook for anything, it’s about how you treat it, and how you mix up your knowledge of the content, other genres and writing forms and your own experience. It’s like mastering in a studio, or whatever.

DG: Is word economy a trait that every author should follow? I ask because word economy typically forces a writer to use words in a better way, even as different parts of speech, or ways that can contradict proper grammar.

TM: I don’t know where I read this, but every sentence is a potential to waste someone’s time. I love that line. That is something that I’ve picked up writing professionally, especially in journalism, where I have wasted a lot of my bosses’ time. But in seriousness, sometimes you have a certain amount of words to express 15 months of reporting, research and investigation, so you have to find a way to compress everything down. Just today I was asked by one editor to give a bridging section more narrative flow “in no more than 9 words”. It almost felt like an instruction from a creative writing class, “make this good and flowing in 9 words.” When you’re pushed by material constraints, or the form of a poem, or how a short story is supposed to move, everything requires your sentences to work harder, so they all earn their place in the text, and so they don’t waste your reader’s time. At a content level, the pleasure of a text is a cognitive one, and compression makes that feel even nicer. You also don’t want to waste your reader’s time, it’s an abuse of the contract between writer and reader.

The flipside of that sense of economy is that you need to think of your resources as being scarce. You have to do so much with so little that the grammatical sense can get wrenched if you’re not careful. I think that accounts for all of the worst excesses in my writing. The surface texture gets clotted and opaque. I mean, it’s a nice trick to make verbs out of nouns, but after a while you end up sounding like an alien, or Craig Raine. This happens to me a lot. He has better trainers than me, and still I let this happen. We’re working on it, though. One of my most trusted readers —he sees everything before anyone else does, and sometimes he’s the only one to see a text, if it’s bad— is threatening to put together a spreadsheet of Tim-isms and we're slowly cutting it down. I'm allowed one of each mannerisms per text. For Christmas, he's getting a story that has none of those shite tics in them. This means he’s probably put together that spreadsheet already. You should see it. It’s dreadful. Nouns verbing everywhere. Entire sentences where you have to play hunt-the-preposition. It’s basically what happens when I’m trying to be Christine Schutt or Lindsay Hunter or Diane Williams, but am in fact shaming myself.

DG: I know that you’re very much into pop culture, and that you feed from its nonsensical modes of behavior and uses of language. Does pop culture have a valuable language of its own?

TM: I feel totally disconnected from the way people speak English these days. Think of it: I live in Mexico, and about 90 percent of my life in Spanish, and my contact with English is generally news, or literature, and rarely speech.

DG: Nothing immediate…

TM: Exactly, they are registers divorced from immediate language. So, whenever I come across something I actually get that’s, like, not the news, and not a novel, and not a poem, I’m like a kid finding a fucking jellyfish on a beach and just get really into looking at it and poking at it. That’s a strange image, but it does capture something of the strangeness of what I’m talking about here. I am a bit obsessed with Paris Hilton and Nicky Minaj. They’re two ends of a spectrum that I adore. I love them on Twitter, and I love them as linguistic entities, floating around on cyberspace. The absolute vapidity Paris expresses —I think probably knowingly at this point, to be honest, sort of like a more physically delicate version of Zlatan Ibrahimovich — sounds like this desert speech, like end times speech, and the fact that she stopped being relevant somewhere around 2003 is even better for me. Nothing is more uncanny than something that is recently dated. It gives you such a bleary sense of freaked-out exhaustion. I mean you can go to Beckett, and you can go to Don DeLillo, and all those other overreacting white men, and they’re absolutely miserable about the death of speech. And I feel as though you can learn so much more about your own exhaustion and emptiness reading Paris Hilton tweets as you can form a grim meditation on Cartesian uncertainties, or whatever. I just think it’s a much more fun way of arriving at a very useful form of self-devastation. So then there’s that end of the spectrum, and at the other you have Nicki Minaj throwing out six-dollar words and short frazzles of nothing in particular, and those happen in the same breath. I think she’s everything. I’m slipping into something I hate in other writers here, where it’s as if they’re deigning to enjoy pop culture, or whatever, like kids from la Roma buying their trainers in Tepito, or whatever, all going for some very cheaply-got credit that doesn’t exist outside their heads, but that’s not happening here. Nicki is the best.

DG: Do you think there’s anything in those modes of expression that can aid high art?

TM: Last year I saw the Jeff Koons retrospective in the Whitney, and, as you walk in, you realize that this baroque overburdening of the rim of a conceptual void is the exact same thing that happens in cathedrals here. You are twisting lumps of matter into Babylonian columns, or things that look like other things, or whatever, and piling up all these layers of money —whether you’re Jeff Koons or an architect in seventeenth-century Puebla— brings you face to face with how culture operates: a celebration of the division of labor. Like, all of these beautiful materials, all of these man-hours put into making a thing or a place gorgeous, none of which you’ve had to do yourself, and all of which you can now consume by flicking your eyes around the room — all you’re doing is celebrating your position in the class system. “It’s great I’m not a worker,” is your appreciation in paraphrase. That’s the jarring effect I think Koons is going for, albeit with a kind of glee that I really wish I could muster myself. You see a giant Michael Jackson posed like the Dying Gaul, and you realize that you’re being conned, same as you are when you see a giant golden altarpiece in Puebla cathedral (I have real problems with Puebla). All you’re doing is looking at another social class’ decoration of spaces that belong to them. You’ve been let in for a quick look at some rich person’s living space, and then it’s back out the door to your position in the edifice.

DG: Language can sometimes be confined and morphed by geography, social class, technology, historical time periods, the clash of cultures. Is technology really morphing language, showing that it can be flexible, or is technology butchering language and diminishing its power?

TM: OK wow, that’s a cool question. I don’t know if it’s butchering and diminishing it, you know. Writing in English puts you in a very anarchic, very open territory. When I was in the university we read a lot of postcolonial theory, and I did linguistics, too, and there was this section on discourse analysis which focused on moving from a prescriptive to a descriptive linguistic model of describing language variants. The takeaway is that there many “englishes”, and there always have them, and, at a personal level, living far away from the word-hub has gives me a sense of the differences between Received Pronunciation and Irish English. When I’m talking with other kinds of English-speakers, or people whose second language is English, or whatever, the sense that no one variant is above the other seems to make the words you’re using sound like a second language by default, because you’re planing away all the usual touches and textures you use when you’re on your home territory. So adding to this there is the technological leap,where people all over the world online are living in a second language; so I think what happens is that our relationship towards word shifts becomes abstract, language becomes something that is happening at a distance from us, which means that the flexibility of language does happen, and opens up to real, ludic possibilities. I personally kill so much fucking time on Twitter, just amusing myself with all the ways I can talk, saying things I don’t mean, putting on a dreadful turgid voice and stuff like that. I have fake accounts as well as my own personal one, for example, where I am just churning out endless crap. Playing with language in this way can in a sense be butchering it, because you’re just playing with it and saying nothing, which is the point you arrive at if you read Derrida for ten weeks during your university years. It would be better to just give everyone a Twitter account for a month, get them to talk bollocks, and then tell them not to bother with On Grammatology or whatever. But putting it into practice is quite a surreal and disturbing thing to do, and it has the converse effect of bringing you back into your real practice as a writer or journalist to the absolute value words can have. So by going to this meaningless playfulness I arrive at the bottom of what words mean for me. The more I abuse this meaningless use of language the useful side of language becomes obvious to me.

DG: So going further, we would say that this is an example of the misuse of language?

TM: A deliberate one, yes…

DG: So, do you think that the poor use of language can be used and conceived as high art? A good example is one of the texts we have discussed in the past, Junot Diaz’ “This is How You Loose Her.” It’s a very intentional misuse of English.

TM: It’s almost Spanglish, right?

DG: Sure, so, how did we get to the point where this is legitimate as high art?

TM: It always has been in my mind, coming from Ireland… language is really weird in Ireland. I come from a rural town, and the regional misuses have become encoded in how I speak, I have very long o’s… so when I go to Dublin to this prestigious university or whatever—“prestigious” in massive quotation marks, because while I loved a great many people in that place, I also hated the place and the institution itself. All I felt, all the time, was these class signifiers flying at me. In real terms, you just look at yourself like this lad with bits of dirt falling off my boots because of the way I speak. I did not look like a Dubliner. I dressed too badly for that. And I had the kind of stupid fucking hairstyle which that happens when someone from the country learns about how “city folk” looked from an Argos catalogue. So to like keep centered or whatever I used to go up the stairs into the library and I’d pass this shelf of dictionaries, and one of the dictionaries was the Terry Dolan Hiberno-English dictionary, which digs out a lot of old words material — it’s amazing— and I’d just flick through to find all these weird monosyllabic shards of English as its spoken by William Carleton, or characters in George Moore, or things like these, words that are more like percussive sound effects, or come at you like particular aromas, or senses of other times and places that break over your palate. They open up imaginary spaces in your head where you can just vanish and hide and feel safe. And when you go back to the Carletons and the George Moores and stuff, you notice that these words do have a literary pedigree of a very particular kind, and when you see them in the wild they’re coming at you beside very baroque, over-the-top, six-dollar kind of words. So it was great seeing these very flowing, elegant sentences, studded with little nubs of weird Irish sound. It captured a lot of the disjuncture I felt in myself, where I was able to perform at an extremely high level academically even while being basically a basket case. And I would compare that linguistic experience to what in Mexico you guys call Español Dominguero. The same class pressures are in operation. Sometimes it pushes out diamonds. Mostly you just end up pulverized, though, which is what happened to the way I write. There are a lot of cunts in Dublin. I left pretty crushed. Toughened, too, though, in a way.

DG: Would you say that the existence of this dictionary separates this sort of speak from slang?

TM: Not sure, but I think seeing it in the library was very consoling for me. Like, here are my words, the words I’m used to, and it’s here in this sterile academic environment full of rich kids. And the point is, I think, that it is a document making a case for Hiberno-English as a legitimate usage of English, even if it is a sub-language within it. And that can go one of two ways, towards this stupid, autochthonous fallacy about a pure, national language — the sort of discourse that gets people killed— or the totally other way, where everybody has a right to the mic, and puts their own twist on speech, and makes something really strange and distorted and great out of it. I don’t know, the thing I’m most excited about in Irish literature is when the Irish versions of Adichie or Hemon start to write, kids who end up drawing on other dictions in their writing. It’s going to sound amazing. Jonny Greenwood kind of shit, you know? All crunchy and strange and great.

DG: A lot of the time when authors employ these sorts of techniques, like the use of slang, or phonetic dialogue, they use the first person. I’m thinking about Thomas Wolfe’s short story “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn,” in which the first person narrator is confined to his Brooklyn vernacular. Junot Diaz also narrates in first person when doing this. The first person in this case becomes an alibi for legitimacy. Would it be justified to employ this in third person? When we assume that the author is knowledgeable about the correct use of language.

TM: The best example I’m familiar with is John Dos Pasos. He was year zero for me. He blasted away everything I’d ever read before. I mean, looking back, his various different accents and worker voices risk sounding like a Harvard student’s idea of ‘how the worker man talk’ —which to a degree it is— but where his characters’ speech comes across as shattered or shredded or diminished, that is kind of the point of his project. You have this vicious machine flailing at his characters’ consciousnesses all the time —I mean industrial capitalism— and leaving them flayed. He could have caught the note better, I think, but the idea behind the endeavor is sound. This is how you talk when your life is a nightmare. This is how you talk when you are alienated from your labor. This is how you talk when you will spend your last $5 on a massive session. Like, it would have been better to use the first person —in the sense that he hand the mic over to someone who’s actually lived this shit, rather than be the kind of class tourist that I am certainly in danger of becoming myself— but as a template, as a manual, his is a great body of work.

DG: Can we only be descriptive of an age by using the language of that age?

TM: I don’t think so. The most garish and gorgeous moments in Shakespeare’s diction can still tell us a lot about how capital operates. He borrows images and items from things he’d heard from colonial voyages, like some kind of extremely materially obvious version of Pinterest. The words are glittering with all the wealth his characters wish they had. It’s the language of want. You catch Derek Walcott parodying of this a lot, using words straight out of Raleigh and Philip Sidney, and using them to talk about the pillages realized on his island and region, leaving it as flat and diminished as the shine off of a credit card.

DG: But do you think that when this is done, using the language of the past, be it intentional or not, are we only alluding to the past and acknowledging it, ore are we really trying to bring it forward and give a place today?

TM: The fact that you’re trying to use it at all indicates that it still has a value. A good metaphor is walking down Alvaro Obregón and looking at the replica Renaissance sculptures. I get such a jarring collision seeing them there. I feel it again like it was 1905, feel that nouveau riche, end-of-days, wish-I-was-in-Paris anxiety. And so what you do then, to bolster your sense of stability in a really charged moment for your class system, is you try to import a sense of the classical, as if you can conjure history down its old patterns, stave off the social collapse. And this is the case now, too, where la Roma wishes it was Williamsburg — Guillermosburgo, I call it. Because we’re in much the same powder-keg instant, I think, where it could all blow if it hasn’t already. We’re just like the Porfiriato people. We want the same things: wealth, stability, comfort. The props are all that change. And their surface differences are pure, historical accident.

DG: Is this not just a touch of nostalgia?

TM: No, not at all, because all these classical meanings and resonances and words still exist now, they just have a slightly more interesting texture because they’ve been beaten to bits. It doesn’t mean the same thing to use words from higher rhetorical registries now as it did before, because you’re not bolstering a class position anymore. You’re referring to something that has already fallen apart. So this produces a very ironic jarring feeling. We can talk about ourselves all we want, but the echoes of the past are always going to drown it out.

DG: Could it be part of a collective unconscious that has existed through the years and hasn’t faded away? I mean, perhaps these things keep resurging because they are part of our ancestry as a society, so bits of it irremediably wash up.

TM: Yes, I think the “wash up” image is great. Rich and strange trash from the past.

DG: Speaking about current times, would you care to guess where is language going? Is it someplace vulgar? Towards extreme abbreviation?

TM: This idea of remixing and combining registries is absolutely nothing new. The same manual is necessary now as it was in the wake of the French Revolution. The words change, but the shape of language and its landscape doesn’t. Think of Chaucer, speaking in the fourteenth century, in Troilus and Cresseida, where he compares language to a geological phenomenon, collapsing, sliding, but somehow constant — even if only as an index of constant change.

DG: How much are we losing of language?

TM: If there is a crisis in speech, it’s just a reprise of some older crisis. The French spoken and read today is the register of a crisis around standards of discourse, ways of speaking, all of which was associated with the emergence of a particular class with a particular, corresponding way of speaking. When you read people after Montaigne, like Corneille or Racine, they have this incredible attenuated diction, because when the Académie Française was founded, they cut all the dirty, peasant, vulgar words, leading French to have infinitely fewer words than it did in the 16th century when Montaigne was writing, or further back, when Villon was around. The hierarchy of registers mirrored the hierarchy of the classes. The dirty, workaday types who supported the glittering edifice were smushed discreetly out of sight.

DG: Is language the only tool of the writer?

TM: Words aren’t just a tool. They’re a narcotic, a weapon, an array of building materials — and tools, of course, to make all those effects happen. I don’t know, I don’t get wasted anymore, but I do get deep into the lulling, vaguely narcotic words have. You sort of lull yourself into an oceanic feeling, a kind of homeostatic contentment. You could go full psychoanalysis and talk about how all you’re doing is looking for an escapism so total that it’s like being back in the womb. But, truly, the combination of form and content means that you can make language into a portable safe space — a house you carry in you everywhere. You don’t you write unless you’re looking for a peace and contentment you can find somewhere else, because why would you go to the bother otherwise? I do feel displaced, and out my comfort zone all the time, and so writing is about the only things that makes me feel centered and safe. Words are all I have that can’t also be taken from me. The rest of my life and environment is an accessory.

4 notes

·

View notes