Text

Chasing the Ghost of a Good Thing

First Death:

Small schools are about the experience. CCU was never going to shape me into some kind of an amazing scholar or brilliant mind. But what it did do for me when I was a goober of a 17 year old was help me to grow up a little. Dr. Faust mentioned it at the last Family, but schools are our alma mater because they help bring us through to adulthood and that was definitely true of my experience there. But life was Extremely Life while I was a student and CCU first died for me when I gave up on it, church, and God in 2004.

Second Death:

And then I came back. Or was invited back. Despite a vow to never return being the least of the terrible things I said about CCU, I was invited back in 2010 to teach adults. I wasn’t even an adult but they trusted me with students who were old enough to be my parents. It was such a great experience that I started full-time in 2014.

I had always imagined teaching as a thing of prestige because I idolized people like Jamie Smith and Donovan Weber. They are both still teaching me how to think about the world in ways that are the good kind of critical.

But then CCU got Extremely CCU in 2015 and sent my friends packing. I spent that Christmas break working on my resume and thinking that it was all over. Birmingham came alive and I learned that teaching isn’t necessarily a prestigious thing but just a vehicle for a person to keep learning themselves.

Last Death:

So in a way, CCU came alive for me again. I scrapped my resume and would regularly look back at the Last Modified Date on that file and smile when it stayed at January 2016 while time and life marched forward. Friends started to tell me what interested them, how they ticked, what mattered. This opened up a whole new world of things to think about and learn.

Zach and Julie and Dana thought getting in the car and driving to Toronto just to hear from people doing good in the world sounded interesting and so we did it.

Brooklin demonstrated how important place was and how what we believe about God has to be expressed in how we live with each other.

Ash and Anj introduced me to people and ways of thinking that I’ll probably never fully understand but want to continue to chase down forever.

Robyn and Mary trusted us enough to let us into the lives of vulnerable people.

And then it all stopped. Fear is a hell of a thing and my bosses got afraid.

No more working with refugees.

No more garden.

No more loving our neighbors.

No more standing arm in arm with people in solidarity.

CCU died again in July 2018. After that, the good things were few and far between. No matter how hard I thought I was trying to recreate those experiences for students, I was mostly trying to recreate them for me. It was easier to be busy than to confront the reality of updating that Last Modified Date from January 2016 to July 2018. Or the reality that without turning all of that energy loose on the world, there was no point in anything I was doing.

Afterlife:

And now it’s dead-dead. No more chasing the good thing that wasn’t there anymore. It’s time to build new good things. I don’t know what those will look like because there will probably never be another job where I basically am given the time, space, and trust to learn with other people.

Maybe that’s for the best. Or maybe it’s just real life. Real life is hard.

All that I know is that there is some comfort in knowing that I can finally let go of those ghosts.

0 notes

Text

I Grabbed the Wrong Inhaler

“You did what?”

“I grabbed the wrong inhaler. This one is empty.”

We landed in Dublin a little after 5a on our way to Birmingham a couple of months ago and settled in for a long layover. Most of the students took a nap and a few explored while waiting for our last airplane across to England. About 30 minutes before boarding, Avery got a panicked look on his face.

“I grabbed the wrong inhaler.”

I honestly wasn’t sure what to do. I’ve been fortunate and have never had any need for medical care when traveling. But this was new. My daughter has asthma and so I know how important that inhaler is and it was clear that the Avery wasn’t going to make it for two weeks without his.

So we shuffled across the airport to the pharmacy hoping that there would be something. As we walked with a little bit of a nervous pace (not too fast!!), I was frantically pulling up the name of the medicine that he uses in the US to see what the European equivalent was called. Nadia’s inhaler costs us $130 a month with insurance and so I was ready to just front whatever money it would take to get my dude through the next couple of weeks.

“How much does your inhaler cost at home?”

“Like $80 a month.”

As we walked up to the pharmacy counter, I had my credit card in my sweaty hands, ready for the worst. Avery told the pharmacist what he needed and asked for enough to get him through those 2 weeks.

“Okay sounds good. Give us 2 minutes and we’ll have it for you.”

She didn’t tell us the price. I thought she was saving us from embarrassment and that it meant bad news. She came back after those 2 minutes.

“Okay just take this to the front and pay. Thanks!”

“That’ll be €5 ($5.50).”

++++++++++++++++++++++++

If the numbers floating around that estimate the increase in insurance premium costs for people with preexisting conditions are true (and I haven’t seen anything countering them), then we move further away from the world that we experienced in Dublin.

In that other world, people who are born with a condition that they cannot control are supported because it’s the moral thing to do. In our world, people who are born with a condition that they cannot control are punished because it’s perceived as the moral thing to do.

In that other world, people who are born with a condition that they cannot control are supported because freedom means a person does not have to worry about choosing between paying the rent and buying their medicine. In our world, people who are born with a condition that they cannot control are punished because freedom is the ability to buy what you want to fit what you need.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

It seems like there are two uniquely American angles to this idea of hanging people out to dry on healthcare.

The first is the idea that if people work hard and make the right choices that they’ll be taken care of. If you want adequate healthcare in this country that isn’t provided by the State, you have to have a job. Lose your job, lose your health insurance, lose your healthcare. The implication is that people who aren’t working don’t deserve healthcare - that people choose not to work and thus should be punished for it. I think that this is a weird and twisted understanding of the Protestant work ethic.

There are a lot of assumptions in this system that miss the mark, but besides being economically inefficient in how this allocates labor, it’s also morally repulsive. A person’s worth is not in their job but this system seems to tie that worth to a job in a more perverse way than a wage does.

The other part of this that seems to be uniquely American is the myth of the rugged individual; that if we leave people to sort things out on their own, that they’ll cut their own way through the jungle of whatever illness they’re facing and come out on the other side. But there is nothing about humans biologically nor is there anything about us socially that indicates we are better off as individuals.

And this ignores the near impossibility of someone to pay their way out of even basic and widely available medicines as simple albuterol if insurance is not available to them.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

Punishing people for their preexisting conditions by having them pay more won’t help get them better. It won’t encourage them to go back to work. It isn’t economically more efficient.

It's ghoulishly cruel for no reason other than scoring political points.

0 notes

Text

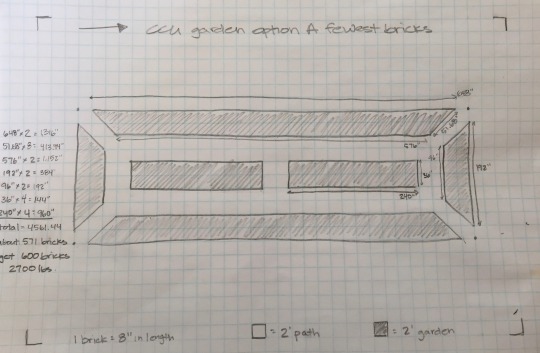

We Built the Dang Garden.

I wrote something about service learning and some of the specific things that we do in Birmingham and how that trip is not about what we do there but what we do at home.

Well we did something at home.

The garden that we helped to build outside of the Winson Green Visitor’s Centre has been something nice for that community. For people who know, it serves as a visual reminder of what happens when discarded things like food or yard waste are reincorporated back into the ecosystem to be food for the plants that help to beautify a place where people don’t normally go to seek beauty.

That garden was dreamed up by a group of people led by Dr. Sam Ewell. Dr. Ewell has studied and written extensively about the intersection of ecosystems and faith, and much of what we’ve talked about comes from the 2015 encyclical by Pope Francis on the environment. In that writing, the pope laments the “throwaway culture” that we all participate in and asks that people of faith take better care to counteract this culture. Dr. Ewell connects the way that we treat earth to the way that we treat people: we see people and relationships as things to consume and once they have no more value for us, we discard them as if they were disposable.

But no one wants to be discarded. And no one should be discarded.

For me, this garden serves two purposes. The first is to finally make that connection between something that we learned in Birmingham and brought home with us. The second is to give ourselves a constant reminder of what it looks like to reincorporate people and things back into the world.

Everything that happens in that stupid garden is going to be a metaphor for the discarded.

Spending hours weeding in the sun to remove some of the seeds from our imperfect pile of rotting debris? Relationships take time and work.

Disappointed that we won’t really have many flowers or beauty in the first year? Relationships aren’t transactional with immediate benefits.

Another piece garden is that it is the first step in my very intentional plan to bring more people from Price Hill to our campus to participate in community. We’re starting with a garden and in the next 3-5 years, I’d like to start a bigger vegetable garden with a CSA so that people in one of Cincinnati’s most economically and socially challenged parts of the city can have the chance to work with the earth and connect with each other.

This garden is the culmination of 30+ people, 5 hours of work, 2 service learning trips, multiple cubic yards of debris, hundreds of boxes, and around 400 days of thinking about why I still treat people as if they were a throw-away commodity for me to consume.

Maybe now I can finally remember.

0 notes

Text

An Apology for the Adopted Brummies

A great part of the annual service learning trip to Birmingham is that it isn’t just a trip for the dozen or so of us that physically leave the country. For those of you that support the students with whatever investments you make in their growth, the trip also has your fingerprints on it. Sometimes people outside of that circle have some legitimate questions that need answered.

[with snark] "How was that vacation?"

[with derision] "I thought you went on a missions trip."

[with genuine curiosity] "So how was England?"

Some of the time spent on our service learning trip and immediately after is spent answering questions like this. I think that the people asking them are well-intentioned. It's tough because there's a tension for the students who take the trip: on one side they sound like they're bragging about service which isn't a good look and on the other side they're not sharing the growth they've experiences in the last week.

In an effort to free them up to do the latter, I'll take care of the former.

First a definition: When we go to Birmingham, we go to do service learning. We don't go to do missions work. We don't go to make it better - Birmingham is already great, thank you very much. We go to encounter, reflect, come home, and then act. More on that is here in Donovan’s dissertation.

Encountering what we do takes many forms. Sometimes those encounters are fun and touristy like a whistle-stop tour of London or chilling in a castle. Sometimes those encounters are talking for hours with someone who took months to cross 2,000 by foot, dinghy, and lorry to finally be safe. More on those encounters is below.

The reflecting time is hopefully something that starts in the seconds we leave a person or place and continues for the rest of our lives. There are experiences from the 2016 trip that still eat at my brain and informed and shaped what we did on the 2017 trip. I would guess that the others who have done this trip twice would have a similar experience.

Then we come home and you ask your well-intentioned questions.

But the last piece is the most important piece. What really matters for this trip - arguably the only thing that matters echoes across our lives and communities - is what we do when we come home. Without that last piece of translating experience into action, the trips are a failure and if I start to experience successive trips that are failures, then the trips stop.

So what did we experience and how will that help to shape our world? Here's a sample:

1. On the first Sunday, a group of students went to the second largest pension in the U.K. That prison exists in a neighborhood, surrounded by houses, in Birmingham. It's a prison that had a riot just a few months ago and some of our learners stepped into that without hesitation. They learned there that the prison is operated by a for-profit company based in America when one of the priests aggressively started to question them on that issue. Through our discussions after around issues of the purpose of justice, the operations of for-profit companies, and how those real life issues interact with faith, these students had the chance to read and respond to The Black Family In the Age of Mass Incarceration.

2. One morning, we did a coffee tasting with an American expat who moved to Birmingham and shared with us stories of what it was like to uproot a life and just go. This isn’t something that just anyone can do - our passport allows us to enter more countries with fewer questions than probably any other passport in the world. So what do we do with that privilege? How do we translate that into making the world better? For Nate, it means buying coffee grown on farms where workers are paid a fair wage and sharing that coffee with other organizations in the city that share his values of rewarding ethical businesses.

3. We went to London for a day. That sounds vacation-y and to a degree it is. But to call it void of learning isn’t accurate. There’s value in seeing the rosetta stone, in encountering a community where you’re the only person speaking English, and navigating one of the most complex and powerful cities of the world. How does a person know how to use public transportation if they don’t actually use it? How can a person have the confidence to get lost in a sea of people without actually diving in?

4. Some of the students spent a half day helping run a youth football tournament. The tournament was for kids who live in that community where the prison is. So most days, these children walk by a prison on their way to school but for that day they got to try and show the scouts from a Premier League team that they might have some kind of value that would let them escape that. The other students spent that day on the campus of the University of Birmingham cooking a meal and talking with their peers who go to that school. In this encounter, they once again had to try and contextualize their privilege among a group of people from all over the world and had to answer the question “why Birmingham?”

5. There was one day (probably my favorite day) where we split out the group into people who spent time gardening in front of the prison visitors’ centre and one group who cooked in a pay-as-you-can kitchen that is run by the Real Junk Food project. I’ll let the students get way into the details on this but the whole theme of that day was working with food that has ben discarded by society and reincorporating it into the food chain so that it can be useful to people and communities that go without. For the group doing the gardening, that meant turning spent bean curd, coffee grounds, and wood chips into compost for a permaculture project outside of the visitors’ centre. People who visit prison tend to be those on the margins of society and aren’t typically treated as though they have anything to bring to a community. That garden and the way that it’ll be in full bloom come July is a colorful reminder of how decidedly false that narrative is. The students who helped with Real Junk Food did a very similar thing but instead of turning wasted food into a garden, they turned it into lunch.

6. One of the most important experiences was when we sat in a room with 4 men who traveled from Eritrea to the United Kingdom in order to escape marginalization and persecution. Sorry, that makes it sound like they just jumped across the street: they started in Eritrea, crossed Ethiopia where they spent time in refugee camp(s), moved through war-torn Sudan, up through Qaddafi’s Libya, across the Mediterranean Sea on a rubber life boat, the north-south length of Europe from Italy to the UK, and then yeah to Birmingham. After that we got to chill with the wider church community that these men are a part of and just listen to them tell us who they are and how we as Americans have the power to speak into a situation thousands of miles away on the eastern tip of Africa.

7. More on that power. We spent part of the day at an Islamic Community Centre where we went back and forth trying to both hear the Imam’s defense of peaceful Islam and speak into that same power that we have as Americans to affect religious tolerance in our own country. I’ve never had a Somali Muslim ask me, “Why is Trump doing this?” I took the question as “Why is Trump blocking Muslims from coming to America,” which might have been wrong, but it’s too late now. She told us that they took heart when they saw the airport protests and that they were happy to meet us because they felt like they were meeting real Americans. For me, that wasn’t comforting or something that I was particularly proud of. 13 people who give away their Spring Break to go to Birmingham isn’t a representative sample and so I was inspired to come back and try to help more of the people I know to become like someone who would be willing to show up at an airport or a park or a community center and clearly call out injustice. Or maybe at a much more microlevel, to understand that how we vote (or even sit out voting) has real and tangible impacts on people half a world away.

8. The other thing that I enjoy is when we get to do The Flavours of Winson Green. It probably doesn’t come as a surprise that the people who live in Winson Green don’t have a lot - most families don’t choose to live within 200 yards of a prison wall if they have the means not to.So the people that do live in that area tend to be newly arrived immigrants or people trying to piece their lives together who have been pushed out of other communities. Flavours of Winson Green is an attempt to show those kinds of people that they have value through what they know and what they can teach us. This year we were taught by a Senegalese woman how to make a soup and a Birmingham-born woman who married a Pakistani Muslim how to make a Balti curry. This was fun! But also humbling! How often do I assume that someone has no value or not enough value for me to invest the time and energy into learning what they can teach me? Literally every day.

There’s more too! Cadbury World doesn’t just have limitless chocolate and a 4D experience but also a lesson in how faith, economics, and community can intersect to make the world better. And if you don’t think the suffering that is endured by being an Aston Villa fan is void of educational experience then buddy have I got news for you.

This is already too long for anyone to read which is too bad.

Someone who is a whole lot smarter than me once told me that often times, we don't choose a place but that a place chooses us. Birmingham chose all of us - students, teachers, supporters - and if we don’t translate that into action that makes our world better then we’ve let that place down.

0 notes