Text

Her Honour was Their Honour

By Rahel Schneider

On February 7th 2005, Hatun Sürücü was killed by her brother Ayhan. He shot her in the head three times at a bus stop near her apartment in Berlin Tempelhof. During the trial he justified the crime by calling on his family’s honour.

Hatun’s tragic death led to a fierce debate in the media on how this crime – a crime which stripped Hatun of her worth as an individual human being, wholly subordinating her to her family – could be committed right in the midst of a country valuing human dignity above all and awarding every citizen the right to personal freedom and development.[1] How was it possible that a boy could murder his sister, both born and raised in Berlin, in the name of honour? Why would someone take a life and break the law for something as impalpable as the concept of honour? From many perspectives there seem to be no adequate answers to these questions; no comprehensible reasons why Hatun and so many others like her have to die. From Ayhan’s perspective, however, there was no other way.

He was raised in a strongly patriarchal and honour-oriented culture his parents imported from their community in Eastern Anatolia. For him as a man that meant he had to be tough, brave and respected. And it was his responsibility as a man to make sure that the women in his family acted according to what was expected of them: loyalty and purity. In those cultures, often emerging in economically unstable environments and lacking a solid judiciary system, family is the most important institution (Brown, Baughman, & Carvallo, 2017). And the family’s most important asset is its honour. This honour hinges on the proper behaviour of the female family members (Stadish, 2014). Hence, improper behaviour on the part of a female family member does not only reflect badly on her, but puts her entire family’s honour in jeopardy. This system of social conduct has been integrated into the institution of family over time and is firmly established in the universal knowledge shared by members of the community. Any sort of violation of this system warrants sanctions (Berger & Luckmann, 2002). In other words, sanctions – in this context honour based violence or honour crimes – are tools to uphold the social structure of the community. Honour crimes are violent actions usually directed at women in order to compensate for a perceived loss of honour brought on by the behaviour of the victim. These actions range from psychological pressure to beatings, mutilations, forced marriages and even honour killings (Prpic, 2015; Gill & Brah, 2014). Since those behaviours are deeply embedded in the social structures of these communities, they are not only practiced in their countries of origin, but are also exported to, for example, Germany or other Western countries when members of the community emigrate (Cooney, 2014). In these cultures the controlling character of the family is so dominant that other cultural assumptions and even institutional rules and laws which originated outside the community, such as the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, are irrelevant or even rejected.

Hatun’s “flaw” thus lay in her openness towards cultural assumptions that deviated from those of her family. Although the Sürücü family lived in Berlin, they held on tightly to the cultural beliefs and traditions of their Eastern Anatolian community. At age sixteen, Hatun was sent back to Turkey and forced to marry a cousin of hers. When she returned to Berlin she was already divorced and pregnant. Hatun and her son moved into their own apartment. She stopped wearing a headscarf but wore make-up instead. She learned to become an electrician, and she dated a German man. According to her younger brother Ayhan, Hatun was “too Western” and thus defiled his family’s honour. Killing her was the only way he knew how to restore it (Höppner, 2018; Kingsley, 2017; Hans, 2011).

While it would be wrong to generalise and equate certain cultures with honour based violence and honour killings, it is fair to say that the way people act is intertwined with their cultural background. Two dominant contrasting perspectives on the relationship between culture and actions have emerged in the field of sociology (Vaisey, 2009). Some assume that culture provides humans with a certain repertoire of skills, experiences, habits and so on, which they can utilise to form strategies of actions. In that sense, culture presents people with different sets of action strategies based on which they can act. However, there is a difference between settled and unsettled culture. In settled culture, the dominant assumptions and values making up that culture are not challenged by competing ideas. Hence, culture provides stable resources for people to form action strategies from. In an unsettled culture, on the other hand, the culture is being challenged by new ideas, which can lead to new strategies of action (Swidler, 1986). In that sense, in unsettled culture actions are run by ideas whereas in settled culture actions are run by habits. Others believe motivation to be the driving force behind human action – motivation being some kind of internal power that impels people to act in a certain way (Weber, as cited in Campbell, 2006). Since the motivations people have are influence by the culture they grow up in, people’s actions are dependent on their culture.

Relating this back to the phenomenon of honour killings, both perspectives seem to play into the initial build-up and also into the final execution of the crime. In honour-oriented cultures reputation is most important. That means that the members of the community have to act in certain ways: Women need to be devoted to their families and men have to protect their families by making sure that the women behave properly. Within those tight-knit communities, life and traditions are highly habitualised and culture is settled. However, mainly younger members of the communities are not only exposed to their traditional cultural practices at home, but also interact with Western cultural practices at school, work or other places outside their communities (Gill & Brah, 2014). Hence, certain elements of their parents’ culture, which they take for universal knowledge or external fact, can be challenged by ideas from outside their community (Berger & Luckmann, 2002; Swidler, 1986). A decrease in engagement with the traditional culture or an increase in interest in other cultural assumptions can cause tensions between family members. Hatun’s fate demonstrates these tensions: By divorcing the man chosen for her by her parents, moving out, taking off her headscarf, putting on make-up, learning to become an electrician and dating a German man, she distanced herself too much from her family’s culture and became “too Western” (Cooney, 2014; Idriss, 2017). She did not act according to her family’s cultural repertoire and thereby disrespected her family. This misbehaviour required sanctions and she needed to be punished according to the action strategies available in honour-based cultures. Especially male members of these communities are put under a particular psychological pressure which impels them to take action when the family honour is threatened (Brown et al., 2017; Campbell, 2006): If the (female) family member’s misdemeanour was so severe that the family name is on the line, the cultural repertoire offers different action strategies a man can take in order to right the woman’s wrong – one of them being the murder of that family member. According to cultural assumptions, this measure is a logical next step. If the man also contains an intense internal motivation within himself, which incites him to restore the family honour, murdering the one responsible for the loss of that honour is the only available action. Hence, the act of killing in the name of honour is at once driven by the selection of a certain action strategy and by an internal motivation.

Does this consideration of culture and action make Hatun’s death any more comprehensible? Not really. It does, however, offer sociological insights into the cultural circumstances that might have moved Ayhan to shoot his sister. On the one hand, his cultural repertoire provided him with action strategies to react to Hatun’s behaviour – her murder being one of them. On the other hand, his internal motivation impelled him to compensate for his sister’s behaviour and to restore his family’s honour. This motivation only allowed for one action: Hatun’s murder.

References

Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (2002). The social construction of reality. In: C. Calhoun, J. Gerteis, J. Moody, S. Pfaff & I. Virk (Eds.) Contemporary sociological theory (pp. 42-50). Malden: Blackwell.

Brown, R. P., Baughman, K. and Carvallo, M. (2017). Culture, Masculine Honor, and Violence Toward Women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(4), 538-549.

Campbell, C. (2006). Do today’s sociologists really appreciate Weber’s essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism?. The Sociological Review, 54(2), 207-223.

Cooney, M. (2014). Family honour and social time. The Sociological Review, 62(82), 87-106.

Gill, A. K. & Brah, A. (2014). Interrogating cultural narratives about ‘honour’-based violence. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 21(1), 72-86.

Hans, B. (2011, July 28). The lost honor of the sürücü family. Spiegel Online. Retrieved from http://www.spiegel.de/international

Höppner, S. (2018, February 8). ‘Honoe killings’ in germany: When families turn executioners. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en

Idriss, M. M. (2017). Not domestic violence of cultural tradition: Is honour-based violence distinct from domestic violence?. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 39(1), 3-21.

Kingsley, P. (2017, May 30). Turkey acquits 2 men in berlin ‘honor killing’ of their sister. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com

Prpic, M. (2015). Combating ‘honour’ crimes in the EU (Report No. PE 573.877) [Briefing]. Retrieved from European Parliament Research Service http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2015/573877/EPRS_BRI(2015)573877_EN.pdf

Standish, K. (2014). Understanding cultural violence and gender: Honour killings; dowry murder; the zina ordinance and blood-feuds. Journal of Gender Studies, (23)2, 111-12.

Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 273-286.

Vaisey, S. (2009). Motivation and justification: A dual-process model of culture in action. American Journal of Sociology, 114(6), 1675-1715.

[1] Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, Art. 1

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Do you really need that much space?”: The sexual politics of manspreading

By Fernanda Rodriguez R.

At the end of September 2018, a video by Russian activist Anna Doygalyuk went viral (Toronto Sun, 2018). In the said video, it is possible to observe Doygalyuk throwing a liquid in the pelvic area of various men on public transport in order to interrupt their manspreading: the male practice or tendency to sit in public spaces with their legs wide open, occupying at least two single seats (Jane, 2017). During the “demonstration”, Doygalyuk accuses the men in her country of gender aggression and her obligation to do something about it (Torornto Sun, 2018). However, one of Doygalyuk’s victims in the video, Stanislav Kudrin, confessed right after the video went viral that the stunt was staged (Torornto Sun, 2018). Despite this, manspreading remains a popular and controversial subject among both men and women. Indeed, the practice was even outlawed from public transportation in Madrid during the summer of 2017, citing the campaign “#MadridSinManspreading”[1] as the reason for the ban (Ahluwalia, 2017). Consequently, theories on gender and symbolic interactionism may provide an interesting outlook concerning this practice, due to the relevance of commonplace interactions and the sexual politics involving the microaggression[2] that is manspreading.

Video: Manspreaders on the Subway

According to Mead (1962), the self is wholeheartedly linked to the social experience. Individuals are able to acknowledge that within any given society there are certain values and norms, which need to be integrated into the self. This process of socialization persists as long as people engage in social interactions (Mead, 1962). Therefore, Mead’s theory presents itself as a gateway for social interactionism, which serves as a micro-theoretical schema that analyzes the actions and perceptions of individuals in relation to one another as the process that shapes social reality (Blumer, 1969). Likewise, Goffman (1959) argues that to better understand the mundane interactions of people, it is best to think of them as actors conducting a performance. Namely, individuals actively devise particular impressions in the presence of others. A decisive element of these impressions are sign vehicles, such as clothes, ethnicity or gender (Goffman, 1959). In fact, gender represents a crucial feature in an individual’s performance.

According to West and Zimmerman (1987), gender is an acquired and enacted status, unlike sex, which is based in biologically received genitalia. They view gender as a resulting element of social circumstances since the classification of individuals into labels such as “man” or “woman” is conducted in a clear social manner, which makes them appear natural thus reinforcing the apotheosis of gender. In other words, the implication that gender distinctions are an intrinsic feature of human beings reinforce and maintain the patriarchal social order (West & Zimmerman, 1987). Moreover, in a social structure in which men exert their dominance and profit from it, the modification of such a system remains disadvantageous for men even when this transformation would benefit society as a whole (Connell, 1987). Accordingly, Jane (2017) argues that manspreading is a clear instance of latent sexism against women since it not solely displays the privileged status of these men, but is also devised as an effective symbol of what it means to be male in a social space.

The problem of manspreading, however, is not a “new” phenomenon as illustrated by a cartoon-campaign founded by CityLab dated back to 1918 (Grant, 2016). Likewise, feminist photographer Marianne Wex conducted a thorough photographic study of the subject in 1979 in her book “Let’s Take Back Our Space: Female and Male Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures” (Bridges, 2017). Nevertheless, it is safe to say that the issue has escalated in recent years. Previous research conducted on the subject of body language has stated that positions involving the “exposure” of genitalia, as well as ample movements are more frequent in men than in women (Davis & Weitz, 1981). Furthermore, historically there has been an enduring social narrative for females of all ages to embrace closed and restrained positions in order to avoid any public display of control and openness (Jane, 2017). To many, these ideas may seem archaic and outdated, but empirical evidence has demonstrated that women’s physical stance nowadays remains in alignment with these confining “ladylike” poses (Jane, 2017). The human body is otherwise disciplined to the structures of inequality within the social order, and the idea that men require - and are entitled to - more space is one type of privilege from which plenty of men benefit (Bridges, 2017). Symbolically, positions that are broad and provide a significant degree of exposure are typically adopted by dominant individuals, while positions involving closed limbs and small gestures are common among deferential and meek individuals that make use of less amount of space (Jane, 2017). The perquisites linked with power carry the implication that individuals may exert their “claim” to behave in a particular manner without taking into consideration the social expectations regarding a specific situation. Therefore, a man that engages in manspreading can be perceived as an individual that it is not solely employing a gender-power marker, but that is also commanding the physical space: the adoption of such a dominant posture has the dual and co-constitutive function of both stimulating and reflecting a state of control (Jane, 2017).

Feminism allows individuals within this social order to challenge the current inequitable structure (West & Zimmerman, 1987). After all, as stated by West and Zimmerman (1987): “gender is a powerful ideological device, which produces, reproduces, and legitimates the choices and limits that are predicated…(p.147)”. Accordingly, feminist activists and groups have adopted a series of strategies in order to fight the “epidemic” of manspreading. First, there is the popular trend of “naming and shaming”: in said practice female activist have opted for taking forthright videos or photographs -occasionally with a somewhat humorous tone and other times in more seriousness- of men displaying obvious signs of manspreading (Jane, 2017). Later, these images are uploaded to social media platforms such as Instagram, Tumblr, among others. A second technique used by anti-manspreaders is that of directly confronting the culprits while also explaining to them their wrongdoing. Lastly, other activists have decided to “fight fire with fire” by sitting in a manspreading-manner on public spaces, sometimes even engaging in “leg battles” with the original manspreaders who try to intrude in their personal space (Jane, 2017). For instance, according to an article titled “Watch out, manspreaders: The womanspreading fightback starts now” by The Guardian, women in various parts of the world are appropriating the practice in the name of feminism (Sanghani, 2017). Big celebrity names such as Emily Ratajkowski, Bella Hadid, and Chrissy Teigen are rejecting the narrative that states that women should sit with modesty and coyness, instead they are sitting with their legs open and sharing the outcome online, thus motivating hundreds more to follow in their footsteps (Sanghani, 2017).

Even if these encounters can be deemed as trivial when they occur as isolated cases of “micro” sexism, Jane (2017) argues that the rationale behind these protests is that when coupled together all these isolated incidents comprise a significant social issue. Namely, a single male commuter extending his dominance over several seats on a train, bus, or tram while other travelers are forced to stand may not be considered more than a small inconvenience at the time. However, this small gesture is but a symptom of a more substantial issue regarding the preservation and imposition of a male-dominated social order. Moreover, Jane (2017) argues that the development of a pattern concerning these “minor” actions may evolve into a powerful emblem of “toxic masculinity”.

Video: When a "lady" manspreads

Nevertheless, the effort of these feminist to stop the practice of manspreading are not without opposition. While the feminist discourses have often made use of scholarly literature to support their claims, most of the claims produced by the male opposition have dubious argumentation (Jane, 2017). The most popular counter-claim is that men require to sit with enough space between their legs in order to guarantee the comfort and protection of their genitals. However, this claim has proved to be completely unsustainable by actual medical data, which conforms with West and Zimmerman (1987) argument regarding the naturalization of constructed criteria that comes with an individual’s biological sex. Meanwhile, others argue that the issue is a matter of etiquette and thus, should be genderless. Moreover, the discourse around manspreading is also often disregarded as merely another rant created by the desperate and troubled minds of feminists. In the meantime, what is certain is that those female activists concerned with the issue of manspreading have been successful at raising awareness regarding the prevalence and universality of this disrespectful practice since campaigns to “stop the spread” have gained a lot of negative and positive media coverage on the international stage (Jane, 2017).

In conclusion, when considering the handling of space in relation to the performance of gender, the matter of power becomes fundamental since space communicates a non-spoken message of individual status (Jane, 2017; Macionis & Plummer, 2012). Arguably, males tend to occupy more space than females, whose femininity has been traditionally associated with how little space they cover (i.e. the positive connotations of the word petite to describe feminine-looking women). Meanwhile, masculinity is often connected to the portion of the area a man dominates (Macionis & Plummer, 2012). Through these interactions that are being challenged by the feminist movement, from which manspreading is a sterling example of “doing gender” in modern times, it is possible to observe the power relations in the everyday of men and women. Women, who more often than not, see their plea for privacy and personal space overtaken by men.

References

Ahluwalia, R. (2017, June 8). Madrid bans manspreading on public transport. Independent. October 3,

2018 from https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/mandspreading-madrid-spain-ban-public-transport-bus-metro-behaviour-etiquette-a7779041.html

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Berkeley: University of California Press

Bridges, T. (2017, February 8). Possibly the most exhaustive study of “manspreading” ever conducted. The Society Pages. Retrieved October 5, 2018 from https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2017/02/08/possibly-the-most-exhaustive-study-of-manspreading-ever-conducted/

Connell, R. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Davis, M., & Weitz, S. (1981). Sex differences in body movements and positions. In C. Mayo & N. M.Henley (Eds.), Gender and Nonverbal Behavior (pp. 81–92). New York: Springer.

Jane, E.A. (2017). ‘Dude … stop the spread’: Antagonism, agonism, and #manspreading on social media. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(5), 459-475. doi:10.1177/1367877916637151

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY: Anchor

Grant, M. (2016, February 10). Anti-manspreading cartoon from 1918 shows that manspreading has been going on for longer than you thought. Bustle. Retrieved October 5, 2018 from https://www.bustle.com/articles/140936-anti-manspreading-cartoon-from-1918-shows-that-manspreading-has-been-going-on-for-longer-than-you-thought

Macionis, J., & Plummer, K. (2012). Sociology: A global introduction (5th ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Mead, G.H. (1962). Mind, self and society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Charles W. Morrised. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Sanghani, R. (2017, November 23). Watch out, manspreaders: The womanspreading fightback starts now. The Guardian. Retrieved October 5, 2018 from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/nov/23/manspreading-womanspreading-fightback-metoo-resistance-physical

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286

Toronto Sun. (2018, September 27). Watch: Russian woman allegedly pours bleach on 'manspreading' train passengers. World News. Retrieved October 3, 2018 from https://torontosun.com/news/world/watch-russian-woman-allegedly-pours-bleach-on-manspreading-train-passengers/wcm/218dcb14-55bb-4665-80be-402c351b2d5e

West, C. & Zimmerman, D.H. (1987). Doing Gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125-151.doi:10.1177/0891243287001002002

[1] In English, it translates to #MadridWithoutManspreading

[2] Microaggression is defined in Sue et al. (2007) as: “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative insults…(p.271)” against marginalized individuals or groups.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I’ll be right back! Just gonna go to the toilet…”: Politeness, Flirting and Rejection

By Maria Indjeian

Many of us have been there at some point or another. Loud music, cocktails and fluorescent lighting seem to be the universally known ingredients that combined form a “fun night out at the club”. Besides being seen as centers for leisure and fun, nightclubs are also highly regarded as the perfect place to find love. This perception is no novelty. In fact, in dense urban environments such as nightclubs, practicing informal sociability, conversation and fun with either acquainted or unacquainted individuals is an implicit universal understanding (Snow et al., 1991; Grazian, 2009).

For the sake brevity, this blogpost will focus on flirting encounters solemnly between members of the opposite sex. In attempt to successfully achieve a romantic and sexual adventure within these contexts, flirting has been determined as one of the most common mediums that men or women practice (Henningsen et al., 2008). The reason? Because it is a collective language that indicates an affiliative desire; believed to increase one’s chances at getting the attention from their person of interest (Henningsen et al., 2008). On the other hand, as skillful as one may be at flirting, it by no means guarantee a positive or aspired outcome, but can rather result in rejection. How is rejection conveyed in a social interaction? How do men and women differ when it comes to facing or transmitting rejection? This article will particularly concentrate on how women and men in communicate a disinterest towards flirting signals.

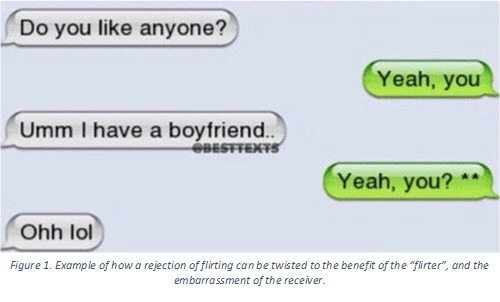

Although substantial research has focused on the execution and dynamics of flirting, the rejection of flirting has often been ignored (Goodboy and Brann, 2010). Nevertheless, research by Goodboy and Brann (2010) has been found that women tend to adopt more polite or non-confrontational strategies when receiving unwanted flirtation. For example, women wanting to leave uncomfortable flirtateous situations may find excuses such needing the toilet, that they do not speak the same language as them, that they must go look for their friends or that that their boyfriend or partner is close by; the possibilities are endless. In many cases, being explicit in not wanting to get involved in a flirtatious activity could make the message easier to grasp; permitting the interaction to terminate quicker all together. Despite some women claiming that they indeed use more verbal rejection strategies such as brief responses, insults or straightforwardness in general to clarify their absence of interest for continuing the flirtatious engagement to its fullest potential (Sutter and Martin, 1991; Goodboy and Brann, 2010), why may some women prefer or adopt a non-verbal, indirect or polite etiquette to communicate the same message?

Goffman’s work on social interaction is key to decipher these circumstances; particularly the development of the “cooling out” concept (Goffman, 1952; Snow et al., 1991). For the sake of clarity, it is important to first determine one of Goffman’s most important terms. “Face” is defined as the image filled with positive socially approved elements that individuals create for themselves and present to the public (Goffman, 1955). In order to “maintain face” individuals have to work hard in terms of performing and keeping the claims they have made of themselves in line front other people through the supportive judgments of others. As a result of maintaining face, individuals have been said to embrace self-confidence, honor and pride. On the other hand, negative social evaluations can lead to “losing face” (Zhang et al., 2011). This can happen due to “slip-ups” on one’s performance that lead to feelings of embarrassment, humiliation and shame (Goffman, 1955; Mao, 1994; Zhang et al., 2011).

The “cooling out” process comes in as an attempt to save face after the “sting”; where the conned strives to adapt the self to the situation as best as possible in order to not feel too humiliated (Snow et al,. 1991). Upon failing to obtain a romantic or sexual relation from flirting and teasing skills towards women, men can find themselves humiliated and embarrassed upon rejection or denial; therefore, losing face.

As Goffman’s examination on social interaction continues, not only do individuals work towards saving their own face during social encounters, but they also make sure to enforce protective practices to save the face of others (Goffman, 1967; Bargiela-Chiappini, 2002). This is done to avoid any feelings of awkwardness and uncomfortableness between the members of the interaction, and work towards a smooth and composed interaction instead. Non-verbal or diffused rejection strategies among women in undesired flirtatious situations could therefore be popular due to the relentless pursuit of a peaceful and tranquil interplay. Instead of denying a flirtatious invitation by using direct language or words that may damage the man’s face by humiliation or embarrassment, women will adopt a “cooling out” process to soften or completely avoid the negative feelings that arise from being rejected in a man (Snow et al., 1991). Women have also shown a desire to stir away from “rude” or “degrading” connotations when rejecting the attention of men (Goodboy and Brann, 2010). In other cases, it could also be argued that by entirely unacknowledging or escaping from the encounter altogether, it is a way for women to avoid witnessing or dealing with the uncomfortable sight of rejection or confrontation due to their actions.

This could relate to the recent rise of “ghosting”[1] in our technological age (LeFebvre, 2017). Moreover, as a result from cooling-out tactics, men would be expected and hoped to abandon the interaction without creating a scene, and fracturing the encounter even further; given that they still find themselves in a very public atmosphere.

Differently to women who employ polite and implicit excuses, men are less afraid to use verbal strategies and insults to communicate whenever they are uninterested in flirting with a woman (Goodboy and Brann, 2010; Sutter and Martin, 1998), What does this say about the role of women under these circumstances? Explanations for this could take us on an entirely different tangent concerning the relationship between the female gender roles and its historical issues of inferiority and submissiveness compared to men in society (Brown, 1980; Zimmerman & West, 1987).

Among many factors, one of the largest causes for assigned gender roles is popular culture such as books, television entertainment and magazines (West and Zimmerman, 1987). By reaching a significant part of the population, popular culture can be said to have become ‘rulebooks’ or “manuals of procedure” (West and Zimmerman, 1987:135) that individuals use to “do” their gender “appropriately”. In the battle towards a more equal and respected position within society, the concern of saving the face of others from saying ‘no’ to flirtatious intimacy with men could be argued to have become less of a priority among women. If a woman rejected a flirtatious interaction with a man by using candid language or mannerisms, she would risk being judged negatively as she would be ‘undoing gender’; hence, failing to accommodate social expectations of femininity for being ‘unladylike’ (West & Zimmerman, 1987). This issue has been understudied; but insight to this question would contribute towards gaining a larger understanding of women’s sense of empowerment and perception of entitlement within these situations.

Men have also been proven to prefer to use non-verbal flirting tactics in order to reduce the risk of getting rejected and losing face. That is to say, rather than being open about their intentions with a woman, men adopt strategies like gazing and eye contact (de Weerth and Kalma, 1995). Using indirect flirting strategies are a good way to save face since in case of refusal; as one could say that flirting was not the intention in the first place. In other words, in attempt to protect and save face upon rejection, men may pretend that their intention was never to flirt and that the woman has misunderstood and consequently become embarrassed herself. In other cases, men may “downgrade the woman’s status to even the score” (Berk, 1977 cited in Snow et al., 1991:429) between them as an attempt to re-gain face; for example, replying something like “You’re not that hot anyway”, or “I was just looking a way to kill time while I wait for my mates”. This said, with women gaining more confidence towards unambiguously denying flirtatious contact with men, could it mean that women would be the ones losing face instead?

Overall, it has been outlined how women are more cautious about the face of others when entering an uncomfortable situation within a social interaction through the work of acclaimed scholars such as Goffman and Zimmerman. Developing more research on the rejection of flirting would allow a larger understanding of the evolution of women’s roles in society. Based on the research presenting a backfiring of losing face in women when it comes to the rejection of men, one could question the effectiveness of the fight against women as submissive and passive members in society.

References:

- Brown, P. (1980). How and why are women more polite: Some evidence from a Mayan community. In: S. McConnell-Ginet, R. Borker and F. Furman, ed., Women and language in literature and society. Oxford: Blackwell.

- de Weerth, C. and Kalma, A. (1995). Gender Differences in Awareness of Courtship Initiation Tactics. Sex Roles, 32(11).

- Goffman, E. (1952). On Cooling the Mark Out. Psychiatry, 15(4), pp.451-463.

- Goffman, E. (1955). On Face-Work. Psychiatry, 18(3), pp.213-231.

- Goodboy, A. and Brann, M. (2010). Flirtation Rejection Strategies: Toward an Understanding of Communicative Disinterest in Flirting. The Qualitative Report, 15(2).

- Grazian, D. (2009). Urban Nightlife, Social Capital, and the Public Life of Cities. Sociological Forum, 24(4), pp.908-917.

- Henningsen, D., Braz, M. and Davies, E. (2008). Why do We Flirt? Flirting Motivations and Sex Differences in Working and Social Contexts. Journal of Business Communication, 45(4), pp.483-502.

- LeFebvre, L. (2017). Phantom Lovers: Ghosting as a Relationship Diffuser Strategy in our Technological Age. In: N. Punyanunt-Carter and J. Wrench, ed., The Impact of Social Media in Modern Romantic Relationships. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp.219-239.

- Mao, L. (1994). Beyond politeness theory: ‘Face’ revisited and renewed. Journal of Pragmatics, 21(5), pp.451-486.

- Sutter, D. L., & Martin, M. M. (1998). Verbal aggression during disengagement of dating relationships. Communication Research Reports, 15, pp. 318-326

- Snow, D., Robinson, C. and McCAll, P. (1991). "Cooling Out" Men in singles bars and nightclubs: Observations on the interpersonal survival strategies of women in public places. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 19(4), pp.423-449.

- West, C & Zimmerman, D.H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2): 125-151

- Zhang, X., Cao, Q. and Grigoriou, N. (2011). Consciousness of Social Face: The Development and Validation of a Scale Measuring Desire to Gain Face Versus Fear of Losing Face. The Journal of Social Psychology, 151(2), pp.129-149.

[1] “Ghosting” – A relationship dissolution strategy where communication is terminated through technological mediums. For example, stopping conversation through text messaging or unfollowing on social media platforms without an explanation to avoid confrontation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cigarettes: the pollution of modern-day society?

By Inge Rots

Many will recognize the anecdote or at least a variant of it, in which people would tell about how back in their younger days, no one would be surprised if, on a party, the host would offer its guests plenty of cigarettes, in the same amount as there would be snacks or beer. Or how, when driving all the way to Spain for vacation, it would be ‘totally normal’ that the father of a young family would smoke inside of the car, while leaving the windows closed. Or how, during class, the teacher would continue smoking while at the same time explaining the workings of the Pythagorean theorem, even though the room would be filled with young, healthy, and above all, innocent children.

These memories stand in sharp contrast with the contemporary relationship of society with cigarettes, that has evolved over time. Currently, several developments coming from various groups of interest, seem to sharpen the debate, both about the question of smoking behavior as an individual choice versus individuals as being exploited and made addicted by the large tobacco industries, as well as the tension between a liberal versus a more conservative approach. For instance, in the month of October, in the Netherlands the campaign of “Stoptober” is being launched, stimulating people to throw away their packs of cigarettes and start living a healthier, nicotine- and smoke-free life (NOS, 2018). This fits within a line of tendencies that focuses on a (moral) reconsideration of what is the best, optimal way of living a healthy, as well as a conscious, sustainable life in which responsibility not just for oneself, but also for one’s surroundings is taken into account.

What is more, since 2016, a large lobby against the tobacco industry, led by a well-known Dutch lawyer (De Volkskrant, 2018), is attempting to sue the big tobacco companies like Philip Morris from murder and attempted homicide, as they are claimed to be consciously making smokers addicted from an early age on, and in doing so, leave smokers without a real own voluntary choice in deciding whether or not to smoke. Rather, they are seen as ‘victims’ of the tobacco industry and should therefore be defended. Yet on the other hand, there is an increasing amount of local governments and campaigns throughout the Netherlands (as well as other countries) that is actively attempting to change smoking policies in public buildings, streets or entire cities, with the underlying aim of making smoking unacceptable and intolerable, in favor of all non-smokers. For example, the Rotterdam municipality wants to make the zone around its biggest hospital, Erasmus MC, smoke-free and with this, involve different institutions such as a high school as well in joining them (Morssinkhof, 2017). Moreover, the city of Groningen is actively attempting to shift the city into becoming even entirely smoke-free as a whole city. (NOS, 2018)

Particularly with the latter trend, the focus is shifting towards a further stigmatization, demonization and patronization of cigarette smoking, inclining towards the idea that smokers themselves are the ones to be blamed. This puts into question the tension between a more liberal versus a more conservative policy; should people be able to have freedom in making their own choices, or should their behavior be regulated? And how exactly are the boundaries within this tension divided? This will be further explored by viewing the phenomenon of smoking and smoking bans through the lens of structuralism.

The main idea of structuralism is that one can only understand something if the structure of relationships towards other elements that are relevant, is also taken into account and attempted to be understood, as only in their relationship towards one another, things will make sense. Thus, it is the structure that counts as meaningful in influencing how society perceives a particular phenomenon. As Cerulo’s (1998) study to newspaper reports on violence shows, it is not so much the content of the message that counts, but rather the context within which the message is presented, hence, the form or structure of the message, that influences the outcome and interpretation of the meaning. Speaking in McLuhan’s terms, “the medium is the message”. For instance, when media are reporting the news story about Rotterdam’s prospective smoking ban, initial differences in ‘sequencing’ could already be observed between different media organizations, resulting in differences in the emphasis on either people on the streets being interviewed about their opinion on the new smoking restrictions, or interviewing for instance the politicians behind the new policy, resulting in different interpretations that either emphasize the stigmatizing of smokers, or the banning of the tobacco industry.

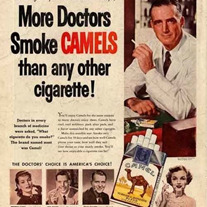

The way in which a society perceives its citizens’ smoking habits, hence, its perception, is a socially mediated mechanism, meaning that nothing one is confronted with can be viewed unprejudiced, as every scheme with which one views the world is based on prior experiences that form expectations of how to approach something new that comes on an individual’s path (Zerubavel, 1997). Hence, the mental lens with which one looks at and interprets the surrounding world, in an attempt to find patterns and categorize knowledge and information in such a way that it fits into our schemes (Douglas, 1990), one is always unconsciously influenced by the social background and context one is placed in (Zerubavel, 1997). For instance, this has (and is still being done) on a large scale by conscious advertising, but also by priming techniques in cinema and on television, that help normalize and stimulate the smoking of cigarettes. Castaldelli-Maia, Ventriglio and Bhugra (2015) explain how particularly in the twentieth century, cinema has played a relevant role in encouraging or even propagating smoking behavior through the direct association with smoking being ‘glamorous’ and luxury, even connecting cigarettes to prominent, classic cinema characters, and in doing so, making tobacco companies benefit greatly from this. It took only until the end of the previous century before it became clear how this promotion of cigarettes through advertising was part of a large-scale effort to hide the real damages of smoking on health (Castaldelli-Maia et al., 2015). In the US, an agreement on banning conscious smoking advertisements in cinema happened in the late nineties, reflecting a historical shift of mental lenses (Zerubavel, 1997), a shift from classifying smoking as normalized towards classifying it as ‘morally bad’. With more knowledge on the deteriorating effects of cigarettes on one’s health, steered and influenced by large developments in health science that are subject to socio-political changes, old facts were subject to a re-examination and re-interpretation, as the marker of a shift into the stigmatization of smoking (Zerubavel, 1997).

This new mental lens through which the majority of society now considers smoking behavior as something bad, favors the smoking bans that are rapidly increasing worldwide (Castaldelli-Maia et al., 2015). Yet, despite of the positive impact of this new legislation, it simultaneously targets the group of smokers with a feeling of being discriminated through a growing public stigma on their behavior, as it has now gained the status of being socially undesirable (Castaldelli-Maia et al., 2015). Yet, as has become clear, this should be considered as being relative and symbolic, since although there is a general agreement upon the idea that smoking is bad for one’s health, “what may be a stigmatizing characteristic in one era may not be in another” (Dovido, Major, & Crocker, 2000 as cited in Farrimond & Joffe, 2006, p. 482).

Nevertheless, although being symbolic, the consequences are not less real: Farrimond & Joffe (2006) show that stigmatization is even becoming bigger with the segregating of public spaces into smoking versus non-smoking areas. What is more, their study shows that non-smokers tend to classify smokers as ‘pollutive’, not only dirtying themselves with the toxic, unhealthy ingredients of cigarettes, but also polluting their environment and especially the non-smoking group of people around them (Farrimond & Joffe, 2006). This fits not only metaphorically, but also literally within Mary Douglas’ idea (1990) that our pollution behavior is a reaction towards anything that contradicts with the classifications within our mental scheme.

Lastly, a structuralist view on smoking behavior adheres to the binary opposition of the ‘good’ non-smokers versus the ‘bad’ smokers not only meaningfulness, as they could not exist without one another, but moreover, it reveals some kind of pollution power (Douglas, 1990) in which this division of society into ‘healthy’ (mostly dominated with middle-class) versus ‘unhealthy’ (not represented by middle-class) becomes a means of legitimizing dominance of this middle-class and thus, serves as a means to reinforce already existing power relations and reproduces a social inequality (Farrimond & Joffe, 2006). Yet, as Douglas mentions, pollutions are fortunately often remedied relatively simply, and the effects can be undone through certain rites, as could be seen with the introduction of the Stoptober campaign. And also, as one man on the street, interviewed by a reporting team argues, there is pollution in the air that we should be really worried about, hence, this said pollutive behavior by the smokers is in this light only relative and symbolic.

References

Castaldelli-Maia, J.M., Ventriglio, A., & Bhugra, D. (2016). Tobacco smoking: From ‘glamour’ to ‘stigma’. A comprehensive review. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 70, 24–33.

Cerulo, K. (1998). Deciphering violence: The cognitive structure of right and wrong. In: Lyn Spillman (ed.). Cultural sociology. Maiden, MA: Blackwell.

De Volkskrant. (2018, February 22). OM ziet geen mogelijkheid tabaksfabrikanten te vervolgen – Advocaat Ficq stapt naar gerechtshof. De Volkskrant. Retrieved from https://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/om-ziet-geen-mogelijkheid-tabaksfabrikanten-te-vervolgen-advocaat-ficq-stapt-naar-gerechtshof~b3a9550a/

Douglas, M. (1990). Symbolic pollution. In: Jeffrey Alexander and Steven Seidman (Eds.). Culture and society: Contemporary debates. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Farrimond, H.R., & Joffe, H. (2006). Pollution, Peril and Poverty: A British Study of the Stigmatization of Smokers. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16, 481–491.

Morssinkhof, L. (2017, July 23). Groningen wil eerste rookvrije stad van Nederland worden. NOS. Retrieved from https://nos.nl/artikel/2184599-groningen-wil-eerste-rookvrije-stad-van-nederland-worden.html

NOS. (2018, August 3). Gaan we langzaam naar een compleet rookverbod? NOS. Retrieved from https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2244453-gaan-we-langzaam-naar-een-compleet-rookverbod.html

NOS. (2018, September 30). Verliefd geworden in Stoptoberhuis, maar stoppen met roken lukte niet. NOS. Retrieved from https://nos.nl/artikel/2252815-verliefd-geworden-in-stoptoberhuis-maar-stoppen-met-roken-lukte-niet.html

Zerubavel, E. (1997). Social mindscapes: An invitation to cognitive sociology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

0 notes

Text

Commodification of racial representation and diversity: The case of Crazy Rich Asians

by Roxi Cui-Olsson

In a better world, “Crazy Rich Asians” wouldn’t have to prove or represent anything but itself. But here we are. – Justin Chang, L.A. Times

In August 2018, a movie named Crazy Rich Asians has been released and quickly became the best-selling romantic comedy in six years at the box office (Mendelson, 2018). The plot is simple: girl falls in love with boy, girl meets the family of the boy, girl and boy get married. The “twist” is that the couple in the story are Asian and Asian American, and the boy’s family is crazy rich. As a matter of fact, they belong to Singapore’s top 1% class and they are not shy to display it. The movie has received positive reviews from critics (a whopping 93% on Rotten Tomatoes), with or without a good reason: it is, after all, the first Hollywood studio production to feature an all-Asian cast in 25 years (Ito, 2018). It makes one wonder, are the critics praising it because it is a well-made movie, or is it due to the backlash of whitewashing in Hollywood in recent years (Rose, 2017)? Is the film so well received because it does justice to representing Asians, or did it merely serve its role as an easy money grab?

#Diversity: “A movement[1]” or good business?

The heavy emphasis on the all-Asian ensemble during the promotion of the movie coincide with a severe social issue at present: the lack of and mis- representation of non-Whites in movies and television series. Morally, it seems like a good idea to support the movie. Indeed, research show that racial minorities are (still) grossly underrepresented on the small and big screen within the U.S. (Atkin, 1992; Maestro & Greenberg, 2000; Monk-Turner, Heiserman, Johnson, Cotton, & Jackson, 2010; Yuen, Chin, Deo, Lee, & Milman, 2005). Even though Blacks and Whites are overrepresented on American TV (Hunt, 2005), Black characters still face inaccurate and inadequate portrayals just like Asians and Latinos, including biased depictions of criminal activities, profession and interpersonal relationships compared to those of White characters (Beeman, 2007; Signorielli, 2009; Soulliere, 2003). Latest media report reveals that, Asians and Pacific Islanders are still treated as “tokens” and old negative stereotypes still persist on the small screen (Yuen, et al., 2017).

Within this context, it is not surprising that mainstream media, audiences and scholars welcome Crazy Rich Asians. The movie is said to have incorporated “universal themes about love, friendship and negotiating family dynamics” into a story consisting of diverse Asian characters (Chiu, 2018b). It is also praised as “a beacon for representation” (Lee, 2018) and a “barrier-breaking phenomenon” (Rubin, 2018). If we were to consider cultural products as a reflection of social structure, undoubtedly, Crazy Rich Asians could be perceived as good news. However, we cannot ignore the fact that Hollywood operates under the rule of capitalism and has every intention of maximizing profits.

“Minorities have become a highly sought-after target for advertisers”, explained communications scholar Atkin on the increase of minority-lead series in the 1970s within the U.S. (1992, p. 337). Even decades later, it is not far-fetched to assume that the purchasing power of Asian audiences influenced the making of Crazy Rich Asians. Even critic Justin Chang (2018) admits that “future Asian-led projects are riding on this movie’s box-office success”. Horkheimer and Adorno (1944/2002) of the Frankfurt School would more than likely refute the idea this movie is as revolutionary or ground-breaking as their marketing suggests, due to its superficial entertainment. According to them, the cultural industry provides amusement that negate the mass from thinking independently or critically, not to mention social change.

Following their logic, Crazy Rich Asians is unlikely going to motivate Asian Americans to fight for their class interest as well as against the social system. It is formulaic at best and does not necessarily provide its audiences with much insight, be it about Asian culture, diaspora, or otherwise. This is likely due to the fact that the culture industry is characterized by rules, norms and conventions (see e.g. Bielby & Bielby, 1994), or in the words of Horkheimer and Adorno (2012), standardization. Intuitively, standardization and diversity are not compatible with one another. Although “cultural diversity” has become popular within media policy-making, research suggests that they are mere business strategies which essentialize and divide cultural audiences even further (Awad, 2012). Sometimes, racial inequality is even reproduced as a counter-effect, especially when cultural producers utilize discourses such as “Asian work for Asian audiences” to justify their hiring and marketing choices (Saha, 2017, p. 312). Additionally, David Oh (2012) suggests that, even when attempts are made to challenge the normative Whiteness in Hollywood movies, there is often an emphasis placed on individual Black or Asian characters to embody their “yellowness and blackness”. This brings us to the next question: is the representation done right in this movie?

Asian #representation on the big screen: Challenging the status quo?

Crazy Rich Asians has also faced some criticisms. Firstly, the film is said to be “not as diverse as many Asians had hoped” as it lacks brown-skinned non-East Asian characters despite the setting in Singapore, spurring social media outrage (Truong, 2018). Secondly, while some people expect the movie to have a positive change on the negative stereotypes and unfavorable impressions that Asian men generally receive (Chiu, 2018a; for empirical evidence on the romantic lives of Asian American men, see Balistreri, Joyner & Kao, 2015), the leading male character is played by a Eurasian actor, whose mixed heritage sparked discussions of whether he is “Asian enough” (Scaife, 2018). Sociologist Nancy Wang Yuen notes that the movie is indeed diverse for Hollywood standards, but it “doesn’t hit that mark” for representing all Asian and Asian American populations as the story is rather class- and ethnicity- specific (Ito, 2018).

I argue that the Asian representation within this movie still features dominant stereotypes about Asians. Instead of “yellow perils” or “model minority” (Yuen et al., 2017), the whole movie is based on a newer version of Asian stereotype, namely, the nouveau riche. The Asian family in the movie hold extraordinary economic capital and purchasing power and are not hesitant to show it off. However, their financial power must not be confused with symbolic power, which Bourdieu (1990) uses to signify the type of power to impose a vision of the legitimate world and its social orders. Indeed, even though the movie is based on an Asian bestselling novel and features an Asian director and cast, it still follows the logic of White normality (Oh, 2012) and ridicules its Asian characters for spectatorship and humor.

The movie reminds us of Fresh Off the Boat (2014- present), which features the same leading female actress Constance Wu. Similarly marketed as the first primetime situation comedy to feature an all Asian-American family in over two decades, Fresh Off the Boat is entirely based on the implicit jokes of an Asian immigrant father who runs a Western steakhouse, and an oldest son who is rebellious and tremendously interested in hip hop, as well as the typical racial/ethnic stereotypes of a “tiger mom”. Both Crazy Rich Asians and Fresh Off the Boat are grounded on the idea that Asian family relations are extremely close, sometimes borderline toxic, who often have values at odds with Western beliefs and norms, such as individualism.

Cultural Studies scholar Stuart Hall has once looked at the significance of representation in popular culture and determined that stereotyping is a type of signifying practice that serves to highlight differences between social groups, and it works by falsely assigning identities to minority groups and therefore “Othering” them (Hall, 2013). Seiter (1986) points out that stereotyping is “an operation of ideology” that not only justifies and reinforces social differences, but also serves to legitimize social inequality (p. 16). The culture industry, particularly Hollywood, still consciously or unconsciously construct a social reality where Asians are perpetually different, and safely placed at the periphery of the society. From a culture as an instrument of power perspective, the tropes of stereotypes can be seen as ways of evoking feelings or amusement within mainstream audiences, hence maintaining the cultural hegemony held by and serving the average White American.

Touted as the poster child for representation and diversity in Hollywood, Crazy Rich Asians is also guilty of treating Asian audiences as uniform but passive consumers, who should be satisfied by the quantity of the all-Asian cast, instead of the quality or the complexity of the Asian characters. However, the fact that the movie features an all-Asian cast is still worthy of celebration, regardless of the potential economic motivation. At the very least, it is better than using the rhetoric of “whitewashing is good business” (Rose, 2017) to justify not employing non-White actors and actresses in Hollywood productions. Perhaps more efforts should be put into creating actually diverse characters that are not based on or against existing stereotypes. Maybe then, the Asian characters we see on the big and small screen might reflect the complexity and varieties of the Asian population on earth.

References

Atkin, D. (1992). An analysis of television series with minority‐lead characters. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 9(4), 337-349.

Awad, I. (2013). Desperately constructing ethnic audiences: Anti-immigration discourses and minority audience research in the Netherlands. European journal of communication, 28(2), 168-182.

Balistreri, K. S., Joyner, K., & Kao, G. (2015). Relationship involvement among young adults: Are Asian American men an exceptional case? Population research and policy review, 34(5), 709-732.

Beeman, A. (2007). Emotional segregation: A content analysis of institutional racism in U.S. films, 1980-2001. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(5), 687–712.

Bielby, W. T., & Bielby, D. D. (1994). "All hits are flukes": Institutionalized decision making and the rhetoric of network prime-time program development. American Journal of Sociology, 99(5), 1287-1313.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). Social space and symbolic power. In In other words: Essays toward a reflexive sociology (pp. 123-139). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Chang, J. (2018, August 8). Review: A flawed but vital milestone, ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ pays exuberant tribute to Singapore’s 1%. LA Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-crazy-rich-asians-review-20180808-story.html#

Chiu, A. (2018a, August 3). 'Asian, ew gross': How the 'Crazy Rich Asians' movie could help change stereotypes about Asian men. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2018/08/03/asian-ew-gross-how-the-crazy-rich-asians-movie-could-help-change-stereotypes-about-asian-men/

Chiu, A. (2018b, August 10). Is ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ Asian enough? The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2018/08/10/is-crazy-rich-asians-asian-enough

Hall, S. (2013). The spectacle of the ‘Other’. In S. Hall, J. Evans, & S. Nixon (Eds)., Representation: Cultural representation and signifying practices (2nd ed., pp. 215-287). London: Sage.

Hunt, D. (2005). Black content, white control. In D. M. Hunt (Ed.), Channeling blackness: Studies on television and race in America (pp. 267–302). New York: Oxford University Press.

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. W. (1944/2002). The cultural industry: Enlightenment as mass deception. In Dialectic of Enlightenment (pp. 94-136). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ito, R. (2018, August 12). 'Crazy Rich Asians': Why did it take so long to see a cast like this? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/08/movies/crazy-rich-asians-cast.html

Lee, C. (2018, August 11). ‘It’s not a movie, it’s a movement’: Crazy Rich Asians takes on Hollywood. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/aug/11/crazy-rich-asians-movie-kevin-kwan-jon-m-chu-constance-wu

Mastro, D. E., & Greenberg, B. S. (2000). The portrayal of racial minorities on prime time television. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44(4), 690-703.

Monk-Turner, E., Heiserman, M., Johnson, C., Cotton, V., & Jackson, M. (2010). The portrayal of racial minorities on prime time television: A replication of the Mastro and Greenberg study a decade later. Studies in Popular Culture, 32(2), 101-114.

Mendelson, S. (2018, September 5). Box Office: 'Crazy Rich Asians' is the biggest romcom in six years, not nine. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/scottmendelson/2018/09/05/crazy-rich-asians-and-silver-linings-playbook-are-both-romantic-comedies/#518f3f1d398d

Oh, D. C. (2012). Black-yellow fences: Multicultural boundaries and whiteness in the Rush Hour franchise. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 29(5), 349-366.

Rose, S. (2017, August 29). ‘The idea that it’s good business is a myth’ – why Hollywood whitewashing has become toxic. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/aug/29/the-idea-that-its-good-business-is-a-myth-why-hollywood-whitewashing-has-become-toxic

Saha, A. (2017). The politics of race in cultural distribution: Addressing inequalities in British Asian theatre. Cultural Sociology, 11(3), 302-317.

Scaife, S. (2018, August 28). Crazy Rich Asians has survived impossible representation standards. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2018/8/28/17788198/crazy-rich-asians-movie-representation-diversity-constance-wu-henry-golding-awkwafina

Seiter, E. (1986). Stereotypes and the media: A re‐evaluation. Journal of communication, 36(2), 14-26.

Signorielli, N. (2009). Race and sex in prime time: A look at occupations and occupational prestige. Mass Communication and Society, 12(3), 332-352.

Soulliere, D. M. (2003). Prime-time crime: Presentations of crime and its participants on popular television justice programs. Journal of Crime and Justice, 26(2), 47-75.

Truong, A. (2018, April 24). Crazy Rich Asians trailer: South Asians criticize film for lack of ethnic diversity and Singaporean accent. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/quartzy/1260412/crazy-rich-asians-trailer-south-asians-criticize-film-for-lack-of-ethnic-diversity-and-singaporean-accent/

Rubin, R. (2018, September 10). What Can Hollywood Learn From #AsianAugust? Variety. Retrieved from https://variety.com/2018/film/news/crazy-rich-asians-black-panther-hollywood-diversity-1202926661/

Yuen, N. W., Chin, C. B., Deo, M. E., Lee, J. J., & Milman, N. (2005). Asian Pacific Americans in prime pime: Lights, camera, and little action [Media Report]. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) on television. Retrieved from https://www.aapisontv.com/uploads/3/8/1/3/38136681/yuen2005.pdf

Yuen, N. W., Chin, C. B., Deo, M. E., Lee, J. J., DuCros, F. M. & Milman, N. (2017). Tokens on the small screen: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Prime Time and Streaming Television [Media Report]. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) on television. Retrieved from https://www.aapisontv.com/uploads/3/8/1/3/38136681/aapisontv.2017.pdf

[1] The director claims that Crazy Rich Asians is “not a movie, it’s a movement” (Ito, 2018).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dirty truth about ‘clean eating’

By Vivian Visser

Anyone who has the slightest interest in food, cannot have missed the recent trend of ‘clean eating’. A search for #cleaneating provides you with no more than 34.349.626 tags on Instagram. Bloggers and food writers such as Ella Woodward, Sarah Britton and the Hemsley sisters are immensely popular, especially among young middle-class women, on social media as well as in the offline world (Wilson, 2017)[1]. So what’s all that fuzz about? For sure, clean eating doesn’t mean devouring cupcakes while mopping the floor. Clean eating champions whole, natural, simple, honest and plant-based foods. It opposes processed foods, such as refined sugar and ready-to-serve meals. According to the advocates of clean eating, it’s not about diets or deprivations. It’s a lifestyle. A form of self-respect; allowing yourself to enjoy delicious food and be kind to yourself and your body. In short, clean eating helps you to live happy and healthy (Baggini, 2016).

Although it’s said not to be a diet, you can now find numerous guides on how to pursue a ‘clean eating diet’. Clean eating will not only make you happy and healthy, but also makes sure you’ll become fit and slender (Irvine, 2016), as is shown by the influential advocates of clean eating, who are all cheery, pretty ánd slim.

It is no surprise that a lifestyle build upon food is especially popular amongst women, when we take into account that food has almost always and everywhere been an inseparable part of women’s lives (Jaggar & Bordo, 1989). Despite the fact that more and more women are currently employed outside the house, providing food still remains a predominant female activity (Hollows, 2003). Food and the body, and therewith dieting, belongs to the female sphere (Bordo, 2003).

Therefore I take a gender perspective to provide an understanding of this phenomenon. I will look into why clean eating appeals this much to young women in our society and therewith reveal a hidden dimension, the dirty truth, of this trend.

Femininity as embodied practice

In particular, gender as embodiment, offers a fruitful approach towards understanding the popularity of clean eating. When we prepare our food, we turn nature into culture. By cutting, mixing, kneeding, boiling, grilling, baking, we transform nature into cultural goods. It’s culture that we ingest and consume. It’s culture that becomes embodied (Douglas, 1966). All bodies are literally materialized through alimentation and dietetic principles, which is why food consumption and dietetic strategies can be considered critical sites for understanding the gendered female body (Spencer, 2013).

Gender is a social and cultural construct, invoked and reinforced on the interactional level, as explained by West and Zimmerman (1987). They distinguish between sex, sex category and gender. Sex is the classification of being male or female based on biological criteria, usually one’s genitalia at birth. In everyday life, placement in a sex category is established and sustained trough behaviour that society recognizes as either male or female. So it is possible to claim membership of a sex category different from the one assigned to by sex criteria. Gender is doing practices that are socially accepted as appropriate for one’s sex category.

Butler (1988; 1990; 1993) continues this line of thinking, saying that gender is a performative act. According to her, it doesn’t even make sense to distinguish between sex and gender, since both are cultural. Both sex and gender only exist within sociocultural meanings and interpretations. Being female then is not a stable identity, but an identity that needs constant construction. Gender is a stylized repetitions of acts, a repetitive performance of gender and an imitation of the dominant conventions of gender. Gender is a performative act in both senses of the word performative: the acts change something in reality (gender comes into existence), and the acts are a performance, based on a social script.

So gender isn’t being, but doing; it is in practices that gender is constructed (Butler, 1988). One embodies the values, ideals, ideas and expectations of one’s time and culture and therewith becomes male or female. This brings about the illusion that something like a stable gender identity exists and produces normative constrains (Butler, 1990). Therefore one is careful not to deviate from the desirable settled standards and conventions. Deviant behaviour will be socially punished (Butler, 1988).

The contradictory constructions of femininity

Let us now return to the clean eating hysteria. What do the clean eating practices tell us about doing femininity in our time and culture? Well, it underscores that the contemporary Western construction of femininity is centred around contradictory ideals, expectations and directives (Woolhouse, Day, Rickett & Milnes, 2011). In short, ideals of passivity and activity are both imposed on women.

Within the constructions of femininity, values such as passivity, dependence and weakness are imbued (Wolf, 2002). Women are seen as consumers rather than producers (Van den Berg, 2012). These values coincide with the domestic constructions of femininity; the woman as caretaker, as the one nurturing the husband and children (Bordo, 2003). In this way, food is strongly related with femininity.

At the same time, it is expected from modern women to be active, to pursue for example a career and exhibit more (traditionally) masculine values (Cairns & Johnston, 2015; Woulhouse et al., 2011). They must learn to embody free thinking and exercise choice around their identities, activities and ways of being. Self-control and determination becomes more and more important. Since food and femininity are that closely linked, it comes as no surprise that the self-mastery of women concentrates around food intake.

Nowadays bodyweight, shape, size and body management are produced as powerful signifiers of the individual’s physical health, emotional and psychological status, morality and beauty (Johnston, Szabo & Rodney, 2011; Burns & Gavey, 2004). Slenderness and restrained eating are highly valued. The imperative for women is to be slim, because this is deemed heterosexually attractive. In the current cultural climate, being overweight is seen as morally weak, deviant, lacking in self-discipline and vulnerable to ill health (Woolhouse et al., 2011).

Already in primary school, young children are aware of differences in preferred male and female food practices. In general, primary school girls are more conscious of the social dimensions of food and eating. Both boys and girls acknowledge that girls should eat less than boys and eat in a more fashionable manner. The awareness is smaller in younger children than in children reaching puberty (Roos, 2002). This underlines the findings that from a young age, the body is continuously disciplined in a gendered way which contributes to the embodiment of gender, through school curricula and family upbringing (Martin, 1998). When it comes to food, girls start to embody the dominant constructions of femininity, as nurturing and restraining, from a young age.

Bordo (2003) asserts that denial of appetites is therefore central in the construction of femininity and a woman exhibiting control over her appetites and desires symbolises moral and sexual virtue. By disciplining the body in this way, the construction of femininity becomes embodied (Waquant, 1995). The embodied food practices of women mediate and reproduce cultural meanings attached to femininity.

Negotiating contradictory constructions

Young women today, implicitly or explicitly, seem to be aware of these contradictory constructions of femininity (Woolhouse et al., 2011). They firmly reject the idea of society imposing certain constraints on their behaviour and meanings. They refuse to be seen as mere passive and indulgent creatures and simultaneously dismiss the ideal of severe self-control over one’s body. Not being passive is shown by actively selecting and restricting one’s food intake. But this must not be done by abiding to the rules of an old-fashioned diet, blatantly aiming at reducing weight, because then one would be trapped by the ideal of an active, thin and attractive body. Hence, young women construct strict dietary rules as undesirable and something that must be avoided. Instead, young women negotiate both dominant constructions of femininity by framing their eating practices as ‘choosing’ to eat ‘healthy’ because ‘you’re worth it’ (Woolhouse et al., 2011).

Clean eating provides the perfect background for doing this. Clean eating offers young women the opportunity to show they’re not passive, while leaving enough room for individual choices. After all, clean eating is not a diet, it’s a lifestyle, aiming for good physical and emotional health, not just superficial slenderness. Young women frame their practices in such a way that it positions them as healthy and responsible individuals, rather than women who give into social pressures of being passive and indulgent or active and thin.

A self-defeating strategy

At first sight, clean eating may seem a nice escape route for young women, to negotiate the contradicting ideals and directives imposed on them. But when we look more closely, clean eating is merely the dominant constructions of femininity in disguise. The healthy weight discourse can serve to legitimate oppressive disciplinary practices that many women engage in to achieve weight loss. It naturalizes weight loss. A slim body equates with a healthy body, and a body cannot be healthy if it’s not slim. When slenderness is framed as a requirement for good health rather than a cultural imperative, it becomes much harder to question and resist (Woolhouse et al., 2011).

When young women frame their eating practices as individual choices and the recognition of one’s own health, this only obscures the highly gendered power relations operating in the sociocultural context. From this, the dirty truth about clean eating, unveils itself: instead of empowering women, by opposing dominant constructions of femininity, clean eating inscribes those dominant constructions on the body. The embodied clean eating food practices therewith confirm and reinforce gender inequalities.

References

Baggini, J. (2016) Clean eating and dirty burgers: how food became a matter of morals. Retrieved on 22 September from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/jul/17/clean-eating-dirty-burgers-food-morals-julian-baggini

Berg, M. van den (2011) Femininity As a City Marketing Strategy: Gender Bending Rotterdam. Urban Studies, 49(1), pp. 153-168

Bordo, S. (2003) Unbearable Weight. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Burns, M. & Gavey, N. (2004) Healthy weight at what cost? ‘Bulimia’ and a discourse of weight control. Journal of Health Psychology 9(4), 549-565

Butler, J. (1988) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519-531

Butler, J. (1990) Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge

Butler, J. (1993) Bodies that matter: on the discursive limits of "sex". New York: Routledge

Cairns, K. & Johnston, J. (2015) Choosing health: embodied neoliberalism, postfeminism, and the “do-diet”. Theory and Society, 44(2), 153-175

Douglas, M. (1966) Purity and Danger. New York: Routledge

Hollows, J. (2003) Oliver’s twist: Leisure, Labour and Domestic Masculinity in The Naked Chef. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 6(2), 229-248

Irvine, B. (2016) On clean eating. Retrieved on 22 September from https://feministacademiccollective.com/2016/07/

Jaggar, A.M. & Bordo, S.R. (1989) Gender/Body/Knowledge. Feminist Reconstructions of Being and Knowing. New Brunswick, Jersey; Rutgers University Press

Johnston, J., Szabo, M. & Rodney, A. (2011) Good food, good people: Understanding the cultural repertoire of ethical eating. Journal of Consumer Culture, 11(3), pp. 293-318

Martin, K. (1998) Becoming a Gendered Body: Practices of Preschools. American Sociological Review, 63(4), 494-511

Roos, G. (2002) Our bodies are made of pizza—food and embodiment among children in Kentucky. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 41(1), 1-19

Spencer, D.C. (2013) ‘Eating clean’ for a violent body: Mixed martial arts, diet and masculinities. Women’s Studies International Forum, 44, 247-254

Waquant, L. (1995) The Pugilistic Point of View: How Boxers Think and Feel about Their Trade. Theory and Society, 24(4), 489-535

Wilson, B. (2016) Why we fell for clean eating. Retrieved on 23 September from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/aug/11/why-we-fell-for-clean-eating

West, C. & Zimmerman, D.H. (1987) Doing Gender. Gender and Society. 1(2), 125-151

Wolf, N. (2002) The beauty myth. Toronto: Vintage Books, Random House

Woolhouse, M., Day, K., Rickett, B. & Milnes, K. (2011) ‘Cos girls aren’t supposed to eat like pigs are they?’ Young women negotiating gendered discursive constructions of food and eating. Journal of Health Psychology, 17(1), 46-56

[1] It must be said that the clean eating trend also encounters oppositions. A nice example is the Facebook event ‘Frikandellen gooien naar de Green Happiness dames op Lowlands’ (https://www.facebook.com/events/106605220059475/). The organizers invited people at the festival Lowlands to throw mince-meat sausages at the Dutch advocates of clean eating, known as the ladies of Green Happiness. More than five thousand people planned to attend. Despite these kind of rebellious and humorous outcries, the success of Green Happiness continues (with over 764.000 followers on Instagram) and clean eating in general remains popular.

0 notes

Text

Injecting gender

By Sabrina Huizenga

In 2016 the Dutch government announced to spend two million euros on educating health care professionals to better deal with vaccination critique (Volkskrant, 2017). While critique usually relates to safety and effectiveness of vaccinations in general, HPV vaccination became especially controversial. HPV stands for Human Papillomavirus, a sexually transmitted infection that effects about eighty percent of sexually active people. Generally, the virus clears itself and has no symptoms. Chances are that most people reading this blog post have (unknowingly) had the virus. Although chances are slim, a persisting virus can lead to cervical, throat, anal and penal cancer (Schurink-van 't Klooster & de Melker, 2016). Nowadays most (Western) governments advise HPV vaccination to young girls to prevent the risk of cervical cancer. While some have hailed this vaccination as a milestone in women’s health, serious critique has also been launched, which is very well captured in the documentary ‘de prik en het meisje’ (Nevejan, 2011). Here, we follow a mother and daughter in their struggle over the question whether to get vaccinated or not. It shows however, that public controversy is generally about safety and effectiveness.

youtube