Text

youtube

Americans Basically Don't Read and It's Embarrassing

The David Pakman Show

0 notes

Text

Book Review

The Room by Hubert Selby Jr.

In pre-modern times before prisons became institutionalized, criminals were punished by shunning or exile; they were either ignored by other members of society or they were sent out of their villages to fend for themselves in the wilderness. Since prisons were invented, criminals have been contained and segregated from the general population and sometimes even segregated from the prison population when put into solitary confinement. Humans are mammals, specifically primates, and so social bonds and community are necessary for survival. Isolated primates become mentally sick. A notorious scientific experiment was once conducted on rhesus monkeys where one monkey was separated from his peer group by a glass wall. He could see them but could not associate with them. He became depressed and angry and when the lab technicians released him back into the rhesus monkey population, he became hostile, aggressive, and violent towards the other monkeys. Solitude had made him insane and so he had to be permanently removed. The main character of Hubert Selby Jr.’s The Room is a lot like that rhesus monkey.

That main character, who I will call the Prisoner because he is unnamed in the narrative, remains isolated in his jail cell, waiting for his trial, throughout most of the novel. Unable to leave, save for meal times, his only escape is inwards into his own mind where he indulges in either memories of his childhood or fantasies involving either his pursuit of justice or indulgences in the torture of the policemen who arrested him.

The first thing to notice in The Room is Selby’s writing style, a continuation of how he wrote his previous novel Last Exit to Brooklyn. The punctuation is minimal and follows Selby’s own invented rules. This makes his prose rush along at a rapid pace. It also demands a lot from the reader in a way that benefits his style; it is difficult to be a passive recipient of information when reading Selby since the writing demands you pay careful attention to what is happening, when people are speaking since there are no quotation marks. The narrative also shifts between first and third person which is something else to watch out for. This benefits the narrative because it shows you who the Prisoner is from an inner and outer perspective. The shifts from third to first person also draws you into his inner world in a way that might not be possible using a different writing technique.

Needless to say, the Prisoner’s childhood memories are not pleasant. Two persistent themes are his relations with the police and a snowballing sense of shame. From a young age, he plays solitary games where he pretends to be having shootouts with the police. Otherwise, his real life interactions with them are not so bad. In one scene, a policeman helps him when he gets bit by a dog. Another policeman helps him when he gets injured. But then there is a suspicious incident where the Prisoner is in a park and a cop hiding behind a bush jumps out and smashes his hand with a billy club then runs away. It’s an improbable story and one that marks the Prisoner out as an unreliable narrator. This is the story he tells his mother when he returns home with an injury. It sounds like the kind of a story a twelve year old would make up if he were doing something he shouldn’t have been doing and was too ashamed to say what really happened.

The theme of shame and dishonesty persist throughout the Prisoner’s childhood memories. Most of these revolve around sex as his thoughts keep coming back to stains on his pants from either urine or semen. Some of the incidents that lead to these stainings are narrated more than once with differences in details each time therefore reinforcing the status of the unreliable narrator. For example, one story he tells his mother is that the urine stain on his pants was the result of an incident with a girl. He says he urinated on her and she got him back by urinating on him; somehow she had good enough aim so that her urine stream landed precisely right on his crotch. Again it sounds like a story a child would make up out of shame for what really happened like losing control and pissing in his pants.

Another stain he gets on his pants is the result of the Prisoner and a girl fondling each other in a movie theater. He has to walk home and performs an excessive cleansing of himself in the bathroom so no one can see the stain left by the semen. And so the theme of shame and the attending cover ups through actions and lies persist. You might also notice the way the Prisoner lies to himself in his jail cell inner monologues to justify his mistakes as if his self-deceptions are the only thread of hope he has to cling on to. His thoughts are just as much of a prison as his cell is.

As he lies in bed, the Prisoner’s mind becomes a stage for the acting out of his fantasies. One involves himself writing an imaginary letter to the press which sparks a government investigation into injustice and police brutality. You might notice that the letter is neither detailed nor persuasive, but in his fantasies it is. This launches into a grandiose story of the Prisoner being lauded as a hero for standing up for justice and speaking out to the media and in the courts. He also daydreams about representing himself as a defendant in court. His cross-examinations of the cops who arrested him are deranged, unrealistic, and absurd. They serve the purpose of confusing the witnesses more than cross-examining them though that really doesn’t matter because the Prisoner’s objective is to humiliate them more than anything. These grandiosities are silly and pathetic, but they reveal a lot about the Prisoner. He is a man with a mediocre mind fantasizing about being a genius, but since he lacks intelligence, his idea of “genius” just looks stupid. It also tells you something else about who he is. People fantasize about what they don’t have. So what kind of man would have grandiose fantasies about being a hero and an intellectual giant? A nobody, that’s who. Also notice that the Prisoner never writes, let alone sends, the aforementioned letter. He only dreams about it because he is a coward and could never bring himself to do such a thing. Indulging in self-pity suits his self-destructive purposes more than being assertive ever would.

Then there are the torture and rape fantasies. In two scenes, the Prisoner imagines himself kidnapping the two policemen who arrested him, taking them to a dungeon, which he calls the kennel, and training them to be dogs in ways that are sadistic and homo-erotic. They read like gay BDSM sessions that have gone horribly wrong. In another scene, he fantasizes about the two cops kidnapping and raping a woman in the woods. If this passage isn’t disturbing enough, then you have to understand that there is a whole other dimension to it. This fantasy is about not just the rape but how the two cops get away with with their it so the Prisoner can use it against them as evidence during the cross-examination during the imaginary trial. Tom Waits once sang “you’re innocent when you dream.” The Prisoner really puts this idea to its ultimate test.

These fantasies make the Prisoner look absolutely repulsive. And yet they are only fantasies and they come from the mind of a chronically lonely man, suffering from inadequacy and shame to the point of despair. He wallows in an inescapable pit of depression and his sadism is an attempt to make himself feel superior to someone else. At some level, these fantasies are also a means of torturing himself. In one part, he imagines cutting off the cops’ eyelids and shining bright lights at them while using eye drops to moisten their eyes. He controls when they are allowed to get the drops in a combination of the psychology of water torture and physical sadism. This transitions into the Prisoner lying on his bed and holding his eyes open for as long as he can while staring at the lights and then closing them to form tears. Those tears are just as emotional as they are for physical relief. He also uses similar language to describe the way the police restrained the woman during her rape and how they restrained him during his arrest while pushing him into the back of the police car. By associating himself with his imaginary victims, we get a sense that his own thoughts are a means of hurting himself.

When the Prisoner emerges from his memories and daydreams, he is alone with his thoughts in his cell and nothing else. He gets obsessed with a pimple on his cheek. Every time he prods at it, the painful thoughts of the police start up again. To him, the pimple is disproportionately painful to what it actually is. To most people, such a blemish would be a minor discomfort but for him it is an excruciating reminder, like the semen and urine stains on his pants, of how worthless he feels. While suffering in his shame and isolation, such a trivial thing becomes magnified to a point of incomprehensible pain.Then while in his bed, his pants get stained again and he has to go to the mess hall trying to hide it from the other prisoners. He begins feeling nauseous and finally admits that nausea has been the only friend he has ever had. You can’t get anymore sick with loneliness than that. There is no way out of his cell, there is no way out of his isolation, and there is no way out of his mind. All three are his inescapable prison.

The subject of this book is a loser. He is a whiner, a complainer, a coward, a weakling, and a failure. His isolation is a double-bind since it causes him to be miserable while his misery drives other people away. Can you blame those other people for ignoring him? You have to admit that you probably wouldn’t want to be around him yourself. He’s just one of those problematic people you’d be better off avoiding. It is a discomforting thought that we might be complicit in this man’s loneliness and despair. On the other hand, by reading this book we get up close and personal with him. At some level, we relate to him. Is anyone happy all the time? Hasn’t everyone felt alone in the world at some point? We may not be as miserable as he is, but we have all been miserable at least once and the Prisoner reminds us of that. It is another discomforting thought that we might have something in common with such an unappealing person.

As unique and provocative as this novel is, there is one major flaw in the prose. There are at least three passages where Selby just goes on for too long. The most memorable one is the scene where the main character and a girl fondle each other in the movie theater. It goes on for a good fifteen pages and, honestly, that isn’t necessary. Once you know what they are doing, it doesn’t need to be excessively explained over and over again. We all know what a hand job feels like and don’t need it to be explained. There are a couple other passages where Selby just plain overshoots his mark. It is also a little too obvious at times that this novel was inspired by Jean Genet’s Our Lady Of the Flowers which, I have to say, is actually a much better work of art.

I can’t say The Room is for everybody. Then again, Hubert Selby Jr. generally isn’t for everybody either. It takes a certain amount of courage and dedication to finish a novel like this. The kind of courage it takes is motivated by the desire to understand someone who is not like we are, someone we would rather not know about, the kind of person most people would ignore. Then it also takes a certain kind of honesty to admit that we might have some common ground with such a person. It gives you a different perspective on life, but maybe one that is tragically important for understanding the human condition.

#book reviews#hubert selby jr#fiction#novels#vintage books#american literature#transgressive fiction

0 notes

Text

Book Review

The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

by Alfred McCoy with Catherine B. Read & Leonard P. Adams II

In the 1970s, Gene Hackman starred in a movie called The French Connection. It tells the story of how undercover American narcotics agents intercept a massive shipment of heroin being smuggled into the U.S. inside a sports car. I can’t remember if the movie ever says exactly where the drugs came from , but it’s likely they originated in Asia’s Golden Triangle and got shipped to New York City via Marseilles, France. The movie was based on a true story and I’m sure the film’s producer was aware of Alfred McCoy’s The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. It shows how there is an impossibly complex history of corruption, politics, greed, and Western intervention that has always facilitated the drug trade and probably alwayw will.

This book combines historical research with muckraking investigative journalism contemporary to the time of its publication in the early 1970s. Of course, that was a time when the drug culture and the Vietnam War were in full swing so it shouldn’t surprise anybody that the two are linked. It starts with a crash course in the history of poppy cultivation, the opium trade, the invention of morphine and heroin, their legal medicinal use in the Western world, and how all of this relates to Asia. Then we get to World Warr II when the OSS, the prototype of the CIA, collaborated with the Mafia to ensure Mussolini didn’t gain power in Sicily. The American government turned a blind eye to the heroin trade in the name of fighting fascism. As the Sicilian gangsters declined in power, the Corsican Mafia stepped in and partially took over. This overlapped with the French-Indochina Wars in the 11950s when Vietnam tried to decolonize and kick the French out. The Corsican Mafia remained in Vietnam though and continued doing business as the Americans took over where France left off. Meanwhile the Viet Minh, who later became the Comunist party, funded their war of anti-colonialism by selling poppies grown by Meo hill tribe farmers in North Vietnam and Laos. At this point you can guess that the story has nowhere to go but down.

There is also a detailed analysis of the Golden Triangle, a region of Southeast Asia including northeast Myanmar, Western Laos, and northeast Thailand. This is where poppy cultivation flourished and heroin manufacturing did too, especially because heroin at every level of production, distribution, and use was 100 percent legal in Laos. And why wouldn’t it be? Every political party and branch of the military had a hand in the narcotics trade. Like in North Vietnam, poppies were being farmed and sold to support the separatist revolutionaries of the Shan state in Myanmar, the anti-communist militias of the Chinese Kuomintang, and intelligence gathering agents of the CIA all in the same region. Drugs coming from the Golden Triangle were smuggled, with help from the Thai military and police, to Bangkok, Hong Kong, and, most importantly, Saigon. These were the major distribution points for the rest of the world.

What’s really interesting about this book is that it accounts for the context of the heroin trade in great detail. To understand how and why it flourished at that time, you need to understand the political and military structures of the countries involved. The two countries that get the most detailed analyses are South Vietnam and Laos. Both countries had trouble establishing democratic rule because politicians and military officials work with supporters and constituents that function more like tribes. Among the supporters are religious sects and criminal gangs along with varieties of other individuals, most of which are corrupt and greedy. These factions work by competing with each other. The conflicts often escalate to territorial disputes, violence, and assassinations so when America was supporting the government of South Vietnam in an effort to cleans the country of communists and nationalists, stability could never be established. Democracy could never function in a place where gangsterism overrode consensus as a method of governing. The result was that America got defeated because they were supporting a government that lacked competency and will, caring about nothing but accumulating riches while thinking of the American military as nothing but a national guard doing their duty of protecting them from the North Vietnamese. The author makes a good point by stating that the blockheads in the America were blinded to the reality of the heroin trade because they single-mindedly fought against the communists rather than taking the whole picture into account. Even worse, they had no understanding of the culture they were trying to dominate. In the end, most of the drugs produced in the Golden Triangle wound up in either US military bases or being shipped overseas to America and Europe while the US allies and enemies in Southeast Asia laughed all the way to the bank. Rampant heroin addicted among US soldiers in Vietnam became a problem and the tribal poppy farmers were stuck in a cycle of impoverishment because other forms of agriculture did not yield enough profits for them to survive. Also, the drug cartels often used Meo tribal people as pawns in proxy wars to fight for different drug running factions managed by politicians and military leaders. As usual, the CIA and American government turned a blind eye to all this just so long as the these drug merchants didn’t support the communists. But then again, some of those merchants did clandestinely support the communists because dealing with them in the drug trade brought them profits and profits meant more than principles. Don’t even try to imagine that much has really changed since the 1970s.

McCoy’s account of the heroin business is a real accomplishment. The details and intricacies are thoroughly explained in a way that makes a challenging read, but is consistently comprehensible if you make the effort to keep track of small details. He doesn’t just focus on the corruption of the authorities and organized crime syndicates either; this book contains a sympathetic understanding of how the poppy farmers are impoverished and trapped by their crops and how devastating opium and heroin are to people who are unfortunate enough to get sucked into the black hole of addiction. This is no work of journalistic entertainment. The complexities of the writing and subject matter make it almost forbidding reading. It is a great work of writing though and also a real eye-opener for anyone who wants to know about the darker side of Southeast Asia, U.S. involvement in the region, and how our government is enabling the drug problems they claim to be legislating against.

In conclusion, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia is probably more valuable as a historical document since a few things have changed since America’s disastrous and foolhardy invasion of Vietnam in the 1960s. Those changes have probably been minor ones though. Poppy cultivation has since moved to Afghanistan and the pipeline of drugs coming from South and Central America up through Mexico and into the U.S. continues to flow unchecked. It just makes you wonder what the CIA is doing these days to keep the supply coming whether its by accident or not. Otherwise, I have spent some time in Southeast Asia and the three countries of the Golden Triangle so I need to say that it has a gorgeous landscape populated by beautiful and kindhearted people with a rich culture; don’t let a book like this ruin your perceptions of this truly amazing part of the world. And finally, don’t EVER try heroin. I’ve seen it wreck people’s lives. Don’t be stupid enough to think you can use it for a weekend recreational high. You can’t. I’ve known several people who have died, one of which was a talented code writer working for Google who overdosed two months after he got married to a woman he fell madly in love with. Please don’t make that same mistake. Do whatever you want with your own body, but don’t ever shoot up junk.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

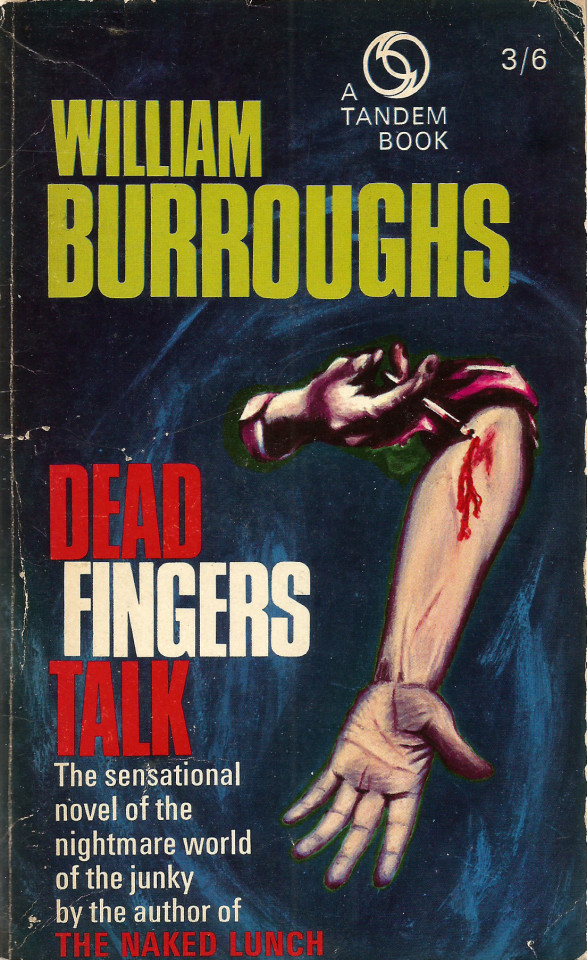

Dead Fingers Talk, by William Burroughs (Tandem, 1966).

From a charity shop in Canterbury.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review

Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby Jr.

This neighborhood in Brooklyn is a vision of Hell that could torment Dante Alighieri. It’s just as poetic too. Hubert Selby Jr.’s notorious Last Exit to Brooklyn takes its readers to rock bottom levels of social depravity. This isn’t a book that utilizes shock value solely for the sake of controversy though. It is animated by an unspoken compassion and righteous anger that would ruin the book’s impact if it were stated explicitly.

Last Exit to Brooklyn isn’t a novel in the conventional sense. It is actually written like the past-together pulp science-fiction novels of the 1950s and done so for the same purpose. It is a series of short stories with overlapping characters and themes, some of which appeared in literary publications before being strung along as a continuous narrative here in novel form. This might cause some confusion to the reader who doesn’t know this beforehand. Once you realize it is constructed like a symphony or a work of modal jazz, it is easier to understand. Maybe that is one good reason to read it twice.

The first thing you might notice from the start is Selby’s unconventional style of writing. He uses Jack Kerouac’s style of spontaneous prose as a springboard and launches into paragraphs with minimal punctuation that follows the author’s own rules. Selby wrote this way so his typing fingers could keep up with his rushing mind since the language traveled at speeds too fast for his body to keep up with. The result is a fast-paced flood of language that resembles the delirium of Arthur Rimbaud’s Symbolist poetry only it is without so much symbolism and maintains a vivid clarity all the way the way through. It makes you feel like you’ve just stolen a car and as you accelerate and drive away at high-octane, speed you suddenly realize that the brakes don’t work and it’s too late to do anything about it. You can risk jumping out, you can keep driving until the gas tank is empty, or you can continue on until you crash and burn, living in the fleeting thrill of the wildest ride in your life.

The first chapter opens by introducing a blue-collar neighborhood in Brooklyn. There are no main characters in the novel; you could actually say the neighborhood itself is the main character. Populated by a gang of hoodlums, drag queens, cops, soldiers, working class men, and anybody else unlucky enough to wander into this rough side of town, it also houses a Greek diner, a dive bar, a labor union headquarters, a factory, and a military base. Nearby is a housing project which enters the narrative in the last chapter.

This first chapter introduces a young thug named Vinnie and his friends. They get their kicks by committing petty crimes, mostly shoplifting and mugging soldiers from the military base who are out on leave. When these kids aren’t beating someone up, they take turns beating each other up. That’s just the kind of world they live in and they live in it with confidence and comfort. The character of Vinnie returns after the next section which simply describes a working-class family party celebrating a shotgun wedding and the birth of a child with the subplot of a guy whose only ambition in life is to buy a motorcycle. In the third chapter, Vinnie is the object of Georgette’s desire. Georgette is a drag queen who turns tricks uptown for money so she can buy drugs and liquor and live the life she wants. In a brutal twist of symbolism, Cupid’s arrow hitting a smitten lover’s heart becomes a weapon of senseless cruelty, Vinnie and his friend torment Georgette by throwing a knife at her over and over again in front the the Greek diner. The fun ends when the knife gets stuck in her leg. Georgette goes home where her brother assaults her for being gay rather than helping her with her wound. Georgette gets through her trauma by desiring sex with Vinnie. A couple days later, she goes to a party with several other drag queens and prostitutes and Vinnie shows up with his friends. They stay up all night eating benzedrine tabs like popcorn and getting drunk. When dawn approaches, it turns into an orgy. Georgette gets what she wants from Vinnie, but is disappointed since it doesn’t turn out the way she wants it to. The end is a spiral into self-destruction that is a precursor for the way the following stories end.

This whole section is beautifully written, almost more like a work of poetry. It is a lot like a literary rendering of The Velvet Underground’s “Sister Ray”, though maybe a bit darker. And on a Velvet Underground record, you get seedy lyrics along with rough, sometimes poorly executed music recorded on lo-fi technology, yet the passion of the music is what matters and it stimulates strong emotions. That is how Hubert Selby Jr. writes and it reflects the kinds of people he writes about. It’s no wonder that Selby had such a big influence on punk rock.

Next up is the story of “Tralala”. The titular character is a prostitute whose johns tend to be soldiers from the nearby military base. When an officer on leave takes her to an upscale bar on Times Square, she goes on a rampage selling sex for money and rolling passed out drunks, but mostly just selling her body. After getting kicked out of that bar, she starts heading downtown, frequenting lower class places rapidly descending downmarket towards sleazier and dirtier drinking holes until she ends up back in Brooklyn. Tralalala does little thinking and any thoughts that enter her head are subservient to her intuition. Her intuition doesn’t do her much good as her purpose in life ends up being nothing but screwing losers for money without even knowing why she does so. Tralalal crashes hard in the end when she consents to pull a train in a parking lot next to a junked, abandoned car. It doesn’t stop there. She pulls every train that passes through Brooklyn and then some until she is abandoned as nothing but a piece of rancid meat in a pile of garbage.

Does this make you uncomfortable? It should and not for the obvious reason. Tralala does everything she can to get herself into such a wretched fix so it is difficult to sympathize with her. This is what is clever about the story: it pushes you to the limits of your empathy and makes you confront the possibility that you may not be as kind-hearted as you think you are. It’s like having an angel on your shoulder saying “Don’t worry about her. She’s a trashy girl who got herself into that mess” while Hubert Selby Jr. wearing a devil’s costume, sits on your other shoulder saying with a lower-class Brooklyn accent, , “Of course you should pity her, you asshole. She’s a human being just like you are.” (Now it’s time to take a break and re-read William Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell.”)

By this point you might see a pattern emerge. Selby writes about people who are trapped in a nightmare world they didn’t create. With limited psychological, social, or economic resources, they don’t have the means to escape so they take whatever path they think is open to them. Just because they make the mistake of choosing the wrong paths doesn’t mean they aren’t striving to be something better. Saint Selby mercilessly challenges you to sympathize with the least desirable people in American society.

So Georgette seeks liberation in romance with a thug who doesn’t respect her and Tralala pursues transcendence by immolating herself in the self-destructive life of prostitution. Now Harry enters the novel in “Strike”, the longest and most developed passage in the book.

Harry is an odd character. From the opening paragraph, we learn that he is more sexually attacted to his infant son than he is to his wife. Nonetheless, every night he has sex with her and then sleeps fitfully while being tormented by nightmares that symbolize his feelings of entrapment. In the daytime, he works as a lathe operator in a metal working factory. He is also the union’s shop steward. As an apathetic worker, he does the bare minimum of labor and spends the rest of his time either doing nothing or stirring up trouble over union rules. The union leaders know he is a fool, but they keep him on as shop steward because he is such a thorn in the side to the factory managers.

When the union contract comes to an end, a strike is called. Harry is put in charge of “managing” the strike although his duties are little more than sitting in the headquarters, stamping the striker’s union books, and getting drunk while listening to the radio. The union leaders give him carte blanche with an expense account and most of the money he spends is on beer and junk food for the strikers. Really, he is being set up as a fall guy in case the union gets into any trouble, legal or otherwise.

The strike grinds on for a long time. While the strikers morale sinks lower and lower, Harry’s sense of self-importance grows. Being the nominal boss of the strike makes him feel like a big shot even though he contributes nothing of any value to the cause. Then he befriends Vinnie and his gang of hoods. They take advantage of him, drinking up all the beer Harry pays for with the expense account, but Harry naively thinks they are his friends. They mark a turning point in the story when the union president hires them on the sly to blow up the trucks of a shipping company that broke the picket line at the factory. More importantly, they introduce Harry to a drag queen who he later pursues in a gay bar. Harry comes out and begins leading a double life that involves gay relationships. You can almost feel happy for him since his nightmares end and begins feeling good for the first time in his life. But this is undercut because at the same time he begins beating his wife who has no knowledge of his alter-ego. Harry thinks he has found his true self and then the strike ends; he goes back to being a mediocre lathe operator while all the elation he felt while being the boss of the strike wears off like a magic spell that has run its course. For Harry, it all ends in tears. Those tears are bloody tears too.

What makes this story so great is hard to explain, not because an explanation is beyond description, but because the story really speaks for itself. Harry runs the course from being an unsympathetic character to someone you can begin to cheer for and then falls back into being a sad and lonely loser in the end. At the peak of the story, you hope that his liberation will help him work out all the anger that makes him violent and irresponsible if he is just given enough time. Harry gains your sympathy and understanding, then while some of that lingers his life descends back into a nightmare existence. He isn’t a great person but that is the whole point. Hubert Selby Jr. isn’t concerned with portraying heroes. He is concerned with portraying the kinds of troubled people we don’t like and asking us to re-evaluate them in terms of the rotten situations they live in.

Finally, the last chapter is not so much of a story as a weaving of narrative threads and vignettes all taking place across the span of a day in a low-income housing project. As all its inhabitants cross paths, we get a picture of a concrete hive in Brooklyn like the inner circle of Dante’s Hell. It’s filled with fighting couples, domestic violence, adulterers, neglected children, alcoholics, delinquent teenagers, snobs, bums, alcoholics, and all around inconsiderate people. To top it all off there is an elderly Jewish woman, living a life of quiet despair in her loneliness, running on the fumes memories she has of her dead husband and a son who got killed in the war. She anchors the narrative by showing us how alone in the world all of us really are and how painful that loneliness is. Under the worst circumstances, we could all end up being just like her. Reading this passage is like listening to some melancholy musical suite in its execution. It brings you into a world that you would rather not be in. Doesn’t that just re-enforce the point that none of these characters want to be where they are anyways? You, the reader, can always close the book and refuse to finish reading. Like the guilty being punished in Dante’s Inferno, these characters don’t have the luxury of escaping. For you, this is the last exit TO Brooklyn; for them there is no exit FROM Brooklyn or at least, they don’t have what it takes to find an way out.. You may not like these people but the least you can do is have some understanding of what they are struggling with. After all, they might be better people if they were thrown into a kinder world.

Last Exit to Brooklyn is crude in its content, style, and execution and that is the point. There are times when it makes you feel like you’re being punched in the head while throwing up and having diarrhea at the same time. Hubert Selby Jr. has commented that he wrote this novel to portray a world without love. He actually said that he wrote about each character out of love. Selby wasn’t a mean-spirited or a sadistic man; in actuality, he was a gentle soul who felt a lot of anger over the human condition. A lot of this resulted from the absence of his irresponsible and alcoholic father and this can be seen in the consistent theme of terrible fathers in this novel. This novel is a picture of city life that he holds up in our faces as if to shout at us about how our society has taken a wrong turn. Along the way he dares us to find it in our hearts to have compassion for those we think of as irrelevant, unimportant, uninteresting, or worthy of our scorn. As repulsive as this novel is, it was written out of courage and we as readers need to be courageous enough to read it.

#book reviews#hubert selby jr#vintage books#vintage paperbacks#vintage novels#fiction#american literature

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Philip K. Dick - A Day In The Afterlife (complete)

BBC Arena Documentary about the author, Philip K. Dick, from 1994. Features Terry Gilliam, Fay Wheldon, Thomas M. Disch, Brian Aldiss, Paul Williams, Elvis Costello, and other friends and fans. Excerpts read by Greg Proops.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review

Opium and Empire: The Lives and Careers of William Jardine and James Matheson

by Richard J. Grace

Imagine some people in a neighboring country, like Mexico for instance, decide that a certain drug, maybe crystal meth or fentanyl, has a potentially giant market in another country like the U.S.A. So they decide to start businesses that manufacture and traffic these drugs. Of course these narcotics are dangerous, wrecking people’s health and causing addiction as well as draining people of their money and landing them in prison; therefore the American government classifies these drugs as illegal, criminalizes their sales and distribution, and labels the businessmen as purveyors of organized crime, drug syndicates, and cartels. But from the Mexican traffickers’ point of view, they aren’t doing anything wrong. They provide work for poor people and make money in a country that isn’t rich. Furthermore, the drug sales provide a steady income whereas other business ventures tend to be less predictable and unstable. Farmers who want to grow produce, like avocados for example, grow some banned substances to keep their finances steady while the market for vegetables fluctuates. This benefits trucking companies too who smuggle drugs in boxes of cucumbers and cilantro across the border, providing work for truck drivers who need to pay rent and feed their families. Of course, a lot of Americans, especially the government and police, think this whole situation is rotten so they fight back hard. Now imagine the Mexican cartels decide to start a war with America to force them into legalizing their drugs so the gangsters south of the border can make even more money than they already do. Eventually they convince the US government to give them the entire city of San Diego so they can have a convenient base for the distribution of their goods. All praise be to Santa Muerte.

This is roughly what happened when the Jardine-Matheson trading company began selling opium on the black market in China at about the same time the Napoleonic Wars began. Richard J. Grace, in his Opium and Empire, tells the story of this nefarious corporation and concludes that they weren’t such bad people and were, in fact, just ordinary businessmen who just happened to do trade in a vice that ruined people’s lives.

You could just as well argue that good things Mexican drug cartels do outweigh the bad. It isn’t fair that dangerous narcotics are illegal in El Norteno and they are really just ordinary gentlemen who provide a service that is in demand anyways. They work hard to earn their money and there’s nothing a red-blooded American capitalist loves more than people who get rich by working hard. Hell, you might even say that the cartels are nothing more than heroes of free market capitalism, letting the invisible hand of the marketplace decide what people buy and sell. Right?

Right?

The story of William Jardine and James Matheson begins in Scotland more innocently than one might expect. Jardine came from a poor farming family and got employed as a surgeon for the East India Company, Great Britain’s colonial trading and shipping monopoly. The younger Matheson came from an upper class family in Edinburgh and eventually went on to work for the East India Company too. He met up with Jardine in India, the two paired up, and went to work as speculators, trading in silk, rice, tea, and, most importantly, opium which they purchased in India and shipped to China.

The kingdom of China at that time was closed to foreigners. They would not allow outsiders to enter their lands for business so they sectioned off a strip of the river bank running along the outskirts of Canton, or what is now known as Guangdong. There they were allowed to build a tiny village of warehouses, factories, and living quarters. Chinese merchants came to the riverfront to do business, buying and selling all commodities except opium which was illegal in China. But Jardine-Matheson insisted on peddling opium since the addiction it caused guaranteed a steady flow of wealth which helped to supplement their more volatile trading goods whose prices fluctuated unpredictably. The Jardine-Matheson company therefore sold opium offshore in international waters to smugglers who brought it onto the mainland. If Jardine-Matheson couldn’t sell opium the legal way, they had no qualms about breaking Chinese laws to make their fortune.

A large portion of this book describes the backgrounds of these two businessmen and the running on their company. It also details how they grew to such prominence as the East India Comany monopoly ended, making room for other companies to enter the competitive colonial markets. Most of this is ordinary business history explaining the methods and functions of Jardine-Matheson. If that is within the scope of your interest, it might be exciting, but actually the writing is often dry and boring. The several passages about finance and banking are especially dull. There is nothing more boring then people talking about money, especially when it gets a bit technical. It is even worse than watching golf on TV.

The story gets more exciting in the run-up to the Opium Wars. After the Chinese government seized and destroyed the entire inventory of opium, Jardine and Matheson pressured the British government to invade China in retaliation and to demand compensation for the lost products. The second Opium War happened when the British colonial government decided to force China to legalize opium for the benefit of British businesses and the extension of British colonial power. Talk about a sense of entitlement. And yes, large numbers of people died over this. Along the way, China gave the mostly uninhabited island of Kowloon, Hong Kong to the British for the sake of allowing them to have a base for business-dealings in the region. So selling illegal drugs on the black market in China was the primary source of finance for building up the British Empire. Maybe in the future, Latin American drug cartels will rule the world.

The end of the book has a long chapter about the lives of Jardine and Matheson after retirement. It isn’t especially interesting. Then, in the epilogue, the author evaluates the Jardine-Matheson company from a moral and historical standpoint. He acknowledges that selling illegal drugs on the black market and starting two wars with China was kind of a crappy thing to do, but he lets them off with a slap on the hand, figuratively speaking, because they were really just a couple of ordinary businessmen who did a lot of good things for their communities back in the British Isles. More importantly, they belonged to some prominent social clubs back home and were considered respectable men by other members of the upper class. Richard Grace goes so far as to say that they were historically important, as if that could even be denied, and their amorality was of little consequence because they were pioneers of free market capitalism. Well, that is actually a weak argument for those of us who are not especially enthusiastic about capitalism to begin with.

And about those Mexican cartels...well they may be harming and endangering a lot of lives, but they are putting people to work and financially enriching their local communities, so it isn’t all that bad, is it? Besides those guys are fun to hang out with wow do they ever throw some fantastic parties and that’s really what’s important. Who cares about all those clucks who buy their drugs on the streets. It’s their own fault they’re losers because they didn’t choose to get a job and work like the rest of us. Right? Yeah right.

I don’t know anything about the author Richard J. Grace, but I can say for sure that we don’t see eye to eye when it comes to values. Opium and Empire tells the story of the Jardine-Matheson company, saying what it needs to say to accomplish that. It is a boring book, however, written by an author with questionable morals. He claims that Jardine and Matheson were not merelya couple of sleazy drug dealers. But just because they hid behind a facade of respectability and a Protestant work ethic, doesn’t mean they weren’t a couple of slimeballs at heart. I don’t think Grace is necessarily immoral, but I get the impression his ethics are in the wrong order. This book does serve a historical purpose, but there has to be an account of this company that is more engaging and a little more balanced. The Chinese perspective on this history is barely even mentioned.

If you visit Hong Kong now, you will find a skyscraper in the center of Kowloon with a unique architectural feature. It is a slender rectangle with its cladding entirely permeated with round windows like portholes. This is the Jardine House, world headquarters of the Jardine-Matheson company which still exists to this day. Because of its unique appearance, the local citizens of Hong Kong have nicknamed it the House of 1000 Assholes. Sometimes I wonder if the people of Hong Kong think back over the times when Chinese peasants became emaciated from lounging in opium dens while their families starved to death because all their income went to feeding their addictions. Maybe that name doesn’t actually indicate how they feel about the Jardine House’s appearance but actually signifies how they feel about all the company’s employees that got rich and powerful by enslaving Chinese people to narcotics. Richard Matheson justified the opium trade by saying he had never seen a Chinaman “beastialized” by opium use. I’m not sure what he meant by “beastialized”, but one thing is certain: while he was running his smuggling business and throwing dinner parties in his mansion, he wasn’t spending time in the opium dens of China, observing how his drug was ruining people’s lives. Just an ordinary businessman? No I don’t think so, but then again take a look at the businessmen of the 21st century. I’m not sure they any better.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Hubert Selby Jr.: I'll Be Better Tomorrow

documentary film

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

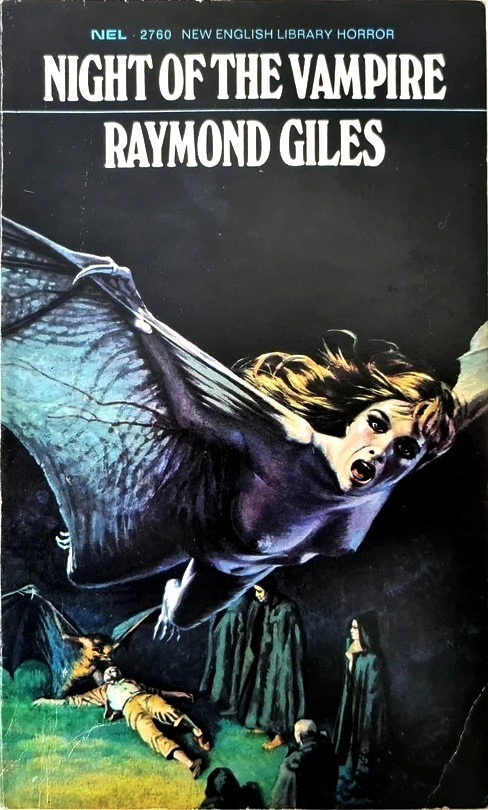

Raymond Giles - Night of the Vampire - NEL - 1970

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review

In the Spirit of Crazy Horse by Peter Matthiessen

I’ve always thought Peter Matthiessen was a terrible writer. I’ll be up front about that right from the start. The fact that he was a CIA agent doesn’t do much to lend him credibility either. But the story of Leonard Peltier and the American Indian Movement (AIM) is important enough for me to overlook the shortcomings of the author and take In the Spirit of Crazy Horse into serious consideration.

This copiously researched and overwrought work on recent Native American Indian history begins with an account of Crazy Horse, Geronimo, General Custer, and the massacre at Wounded Knee in South Darkota. After some commentary on stolen land and treaties that were never upheld by the U.S. government, the story is brought into more recent times by briefly telling the story of AIM and how leaders like Russel Means, Dennis Banks, John Trudell and other lesser known men formed the militant activist group at the end of the 1960s. The group was loosely organized and made up of urban Indians, mostly from the West coast. They came into prominence in the early ‘70s when they occupied the Oglala reservation of Pine Ridge, South Dakota. This led to a brief standoff with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the FBI that brought AIM into the spotlight of national politics and won them support among Native peoples all across the country. Matthiessen follows this section up with an account of the trials that came after.

Up to this point, the story is straight forward and easy to follow since it goes along an ordinary linear path. Matthiessen’s style is not known for being direct, precise, or clear, but in these opening chapters he manages to keep a tight rein on his language so the audience doesn’t get lost so soon. The opening chapter on Wounded Knee feels arbitrary and unnecessary, especially for anybody who knows about American history. It could have been left out or shortened, but it doesn’t do any real damage to the book. The problems come later. At least these sections do a good job of setting the tone and context for what comes next.

What does come next is the whole heart of the story. In June of 1975, two FBI agents drove onto the Pine Ridge reservation with a huge entourage of FBI and BIA agents, SWAT teams, a gang of thugs, and a right wing militia group, while a spotter airplane flew overhead. A group of AIM members were camping on the reservation with a cache of weapons. Nobody knows how it started, but a firefight began. The two FBI agents were shot point blank and one AIM activist named Leonard Peltier was later charges and convicted of murder.

This whole chapter is confusing. I have to say, that is not Peter Matthiessen’s fault. He tells the story several times from the points of view provided by several different witnesses. Since most of them were either firing guns or hiding to avoid being shot, you can’t expect any of them to provide a clear explanation of what happened. As muddled and difficult as this part of the book can be, Matthiessen still holds your attention enough to keep you reading and guessing what will happen.

The inevitable next section of the story is the arrest of Peltier and some others and their two trials for murder. The prosecution does a terrible job in both trials, resulting in a finding of not guilty in the first and guilty in the second, the one in which Leonard Peltier got sentenced to life imprisonment. Matthiessen demonstrates how insufficient the prosecution’s case was in both and how they broke the law in their conduct by intimidating witnesses, tampering with evidence, and withholding necessary documents from the defense. If Matthiessen’s account of these trials is accurate, then there is more than sufficient reason for Peltier to be allowed a retrial. If Matthiessen’s account isn’t accurate, then it is because he is guilty of massively cherry picking his information. Given what I know about Leonard Peltier, I think the former is more believable than the latter and I would prefer to just go along with the author. But what comes later in the book, or more accurately what doesn’t come later, gives me reason to pause and question how trustworthy the author is.

From a simple standpoint of excitement, the beginning of the last section is the most interesting. The imprisoned Leonard Peltier learns of a supposed plot to assassinate him, so he escapes from the penitentiary, only to be caught soon after. If you want any more action to keep the narrative going, you will find it here. This incident leads the author to assert that there is some sort of conspiracy by the FBI to bring down the American Indian Movement. Matthiessen’s theory is that they are working with some corporations to access uranium mines in the Black Hills on the Pine Ride Reservation. Is it a real conspiracy or just a conspiracy theory? We know that the FBI tried to take out other Civil Rights organizations along with other activist groups of the New Left in the 1960s, so it isn’t a far fetched idea. As to why they chose to go after Peltier even though they probably knew he wasn’t guilty, is a bit more complex. It appears they needed to pin the murders on someone, even if it wasn’t the actual murderer and they found it easier to build a case against Peltier than anyone else. As for the assassination plot, I just don’t know. The FBI had Fred Hampton of the Black Panthers assassinated so it can’t be ruled out even if there is testimony from only one man regarding this.

The rest of this last section involves Matthiessen rambling around, talking to various people about various elements related to the case. Except for the two people who claim to have murdered the FBI agents, there isn’t anything here that actually strengthens the author’s argument. It is a disorganized mess of random stuff that is barely, if ever, interesting. It seems that Matthiessen felt he had to include all the information he had gathered even if it didn’t contribute anything of value to the book overall.

The biggest problem with this last section is not its bad writing, but the way in which it makes its one-sidedness so obvious. I have to say that I mostly agree with the author’s stance on the issues addressed, but the absence of opposing points of view make it look suspicious. There is one passage where the author has a phone conversation with FBI agent David Price, but Price does little more than talk in circles without ever saying much of anything. He obfuscates the FBI’s case rather than clarifies it. It doesn’t stand firmly as an attempt at providing a counter-argument. Matthiessen should have cut down on all the testimony from AIM members and sympathizers, who sound like nothing more than yes-men and yes-women, and included more from the government’s point of view. It would have made the story more complete and I don’t think it would have hurt his thesis. It probably would have strengthened it.

Is In the Spirit of Crazy Horse worth reading? For now, I have to say yes. The history is interesting enough on its own to survive the bad writing. And as far as I know, this is the most well-researched and comprehensive account of the Leonard Peltier affair that is available. Still the question remains, did Leonard Peltier kill those two FBI agents? I really don’t think so, but I also don’t think Peter Matthiessen did a good job of proving his innocence. What he does succeed in is showing how the trial was a sham, a persecution motivated by extreme prejudice and not by a desire for justice.

#book reviews#peter matthiessen#leonard peltier#american history#native americans#american indians#american indian movement

0 notes

Text

youtube

Bill Hicks "What are you reading for?"

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“One man practicing kindness in the wilderness is worth all the temples this world pulls.” - Jack Kerouac

Photo of Jack, by Wilbur T. Pippin.

443 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review

Arabs Without God by Brian Whitaker

Being an atheist or agnostic in America isn’t easy. Bigotry, religious fanaticism, intolerance, and anti-intellectualism run rampant here and this is a country where the First Amendment is the cornerstone of our Constitution. Being secular-minded in Arab countries in the Middle East and Africa is even more dangerous, being a part of the world where human rights aren’t respected, governments are authoritarian and autocratic, and Islam is the dominant form of cultural expression. In most Arab countries, Christians, Jews, and members of other smaller religions like the Druze, Alawites, and Zoroastrians are regarded as second-class citizens. Muslim sectarian fighting between Sunnis, Shias, and various other denominations is common too. In a region permeated with religious strife, having a rationalistic, scientific, or skeptical outlook can be deadly for so most Arab atheists tend to stay silent or pretend to be religious to avoid persecution. In Arabs Without God, British journalist Brian Whitaker gives an in-depth analysis of the cultural and legal climate of Arab societies and explains what it means to be an atheist in such places.

As the internet penetrates Arab nations, people who had long been silent about their disbelief are coming into contact with others of like mind. Secular Muslims, mostly those who are highly educated and familiar with other cultures, find they aren’t alone and write blogs, discuss their beliefs in chat rooms, and use social media to contact other atheists and agnostics. When the governments and religious authorities learn about this, they crack down hard on free-thinking Arabs. They send atheists to prison, harass them and their families, and, in some cases, forcehem into exile in Europe or America. In many cases, the families and friends of atheists break off contact with them, although some find that they have parents or family members who have kept silent about their skepticism all their lives. In the patriarchal world of Islam, female atheists are in an even bigger bind because women are traditionally expected to be submissive and subservient to men so by coming out as atheists, they risk even more danger and degradation.

This book is divided into two sections. The first is about the history and culture of atheism in Arab nations. Whitaker examines the history of atheism in the Middle East, proving that such skepticism is nothing new in the region. This was the weakest part of the book as he does not provide any real sources of Arabs with arguments in favor of non-belief in God. He does provide some good examples of intellectuals and poets, going back to the dawn of Islam, who expressed doubts about religious belief without actually coming out and saying they disagree with Islam. Whitaker then goes on to examine reasons why Arabs turn to atheism and scientific thought, most of the time a result of listening to Muslims and observing their behavior. Religious leaders have often blamed the West for bringing science and skepticism into Arab countries or otherwise falling back on the old trope that Jews are spreading atheism amongst Muslims to destroy their religion. Yeah, as if Jews have nothing better to do with their lives. Some people have concluded that religion is just silly, hypocritical, and sometimes even dangerous. The whole section ends with a chapter on gender in Arab societes and the suppression of gays and lesbians who often risk imprisonment, violence, and even corporal punishment for coming out as non-heterosexuals. The whole point of this chapter is to show how dangerous it is to be secular in Arab countries.

The second section of this book is more dense and rigorous as it examines legal codes, morality, government autocracy, religious intolerance, and Arab traditions to show how complex Middle Eastern society is. Muslims can be fanatical about proselytizing Islam while often making it illegal to proselytize for any other religion. Conversions to other religions is usually frowned upon and sometimes not even recognized by government officials if it is even allowed at all. Sharia law and government practices are vague, confusing, and arbitrary. The Qur’an and the Hadiths are full of contradictions and outdated rules. Living as a Muslim in a theocratic or autocratic dictatorship requires submission to authority, even when the laws make no sense. If such is the case, then being an atheist, a member of a non-Muslims religion, or even a scientifically minded Muslim can be treacherous. Minorities run the risk of committing the crime of apostasy simply by being themselves and in many Arab countries, apostasy is punishable by death. It is no wonder that many Arab atheists emigrate to more tolerant countries in the West. This second section does not comment much about atheism in and of itself; what it does do successfully is show how complicated it can be to think for yourself in such repressive societies.

The book finally ends with Whitaker making a plea for greater respect for human rights in Arab societies and equality for those who disagree with the dominant modes of thought. Finally, he takes both the Western right and left to task for treating Arabs and Middle Eastern people as monolithic societies. The xenophobic right sees them as nothing but evil incarnate and the left sees them as being angelically perfect beings who can no no wrong. People on both sides do more harm than good by holding such attitudes. Leftist accusations of Islamophobia are extremely damaging because some Arab atheists, as well as some Muslim human rights activists, have been shunned and attacked by the left, using the epithet of Islamophobia to shut down conversations about human rights abuses in Islamic countries. This is inherently racist, preventing people in Arab nations from defending the rights of women, racial minorities, and LGBTQ people by forbidding discussion on these issues in the name of tolerance. These problems can never be solved if people, especially the people who are affected by them, are silenced in the name of tolerating Islam. A lot of Arab atheists immigrate to the West so they can have more safety and freedom of choice, but then find themselves being hated by leftists for not being authentically Arab in their rejection of Islam. Being a marginalized person in any society is not easy, but it is worse when marginalized people get rejected by those who claim to defend marginalized people because they don’t fit into the stereotype they are supposed to inhabit.

Arabs Without God is worth reading because it gives an in-depth look at Arab societies from an alternate point of view, one that you may not get from any other source. Even if you aren’t interested in atheism or agnosticism, it gives another perspective on Arab societies that is unique and provocative. In conclusion, it must be said that Brian Whitaker is not concerned with converting Muslims or people of any other religion to become atheists or abandon their cultures. He clearly states that he has nothing against religious people. What he wants is for people to tolerate atheists and repect their freedom to choose, allowing them right to human dignity that they deserve. If that bothers you then you might be a bigger problem than any secular humanist ever has been. If your belief in religion is so strong then it shouldn’t bother you when others hold opposing beliefs. If it does, then you aren’t as secure in your faith as you think you are.

0 notes

Text

Book Review

The Dream Palace Of the Arabs by Fouad Ajami

The Middle East is planet Earth’s permanent snafu. While the troubles there didn’t start in the 20th century, it is clear that the Arabic lands since World War II have been a continuation of their turbulent past and a sad precursor for where they are heading in the future. Fouad Ajami takes a look at modern Arabia and shows how it relates to the ideologies of Arab intellectuals in The Dream Palace Of the Arabs.

The Arabian lands span an arc across the globe from western Africa to Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula in the east. Most of what Ajami writes about is in the middle of this region with the heart of it all being in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt. The work begins in post-World War II during the time of Arab Nationalism. Using the frustrating life of Syrian poet Khalil Hawi as an anchor for the narrative, Ajami shows where Arab Nationalism came from and why it failed. In the postwar world, Arab intellectuals were eager to break free from colonialism and European domination while they were simultaneously fascinated by European ideologies. Not just nationalism and modernism but also socialism, communism, capitalism, and even fascism became part of the intellectual lives of poets, novelists, college professors, and journalists. Any kind of “ism” that spread out of Europe at the time got embraced by this small class of educated people. It was Arab Nationalism and Pan-Arabism that eventually emerged as the most dominant forces. Pan-Arabism failed in its attempt to unite all the Arabic people under one ethnic umbrella, be they Muslim, Christian, Jew, or anything else. Tribalism and sectarianism proved to be stronger markers of identity than ethnicity. Regional differences were too vast and Arab Nationalism took over. Arab intellectuals pushed people to unite within national boundaries; it embraced the blood and soil element in fascism This was doomed to failure too because of so many sectarian differences. In addition a lot of Arabic people hated their leaders, making nationalism a dim hope. The dreams of Arabic unity shattered and Khalil Hawi committed suicide in despair.

Ajami continues on with Middle Eastern history in tandem with the poets Nizar Qabbani and Adonis. This section covers the time period from the 1960s or so up until the Gulf War when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Both poets continued on expressing their desire for Arab unity and their muted disgruntlement with the growing autocracy amongst Arab politicians. Three majr events disillusioned Arab intellectuals even further. One was the Iranian Revolution, the time when the Persian, non-Arab Muslims asserted themselves as the world leaders of Muslim ideology and political power. Even worse, the Iranians were predominantly Shia and this set off a long series of clashes between Sunni and Shia Muslims in the Arabic lands. The next big obstacle to Arab unity was the oil industry boom on the Arabian Peninsula and the rise of the petrodollar. Suddenly Saudis, Emiratis, Kuwatitis, and Qataris saw themselves as richer and superior to the other people of poorer Arabic nations and they didn’t hesitate to show it. Then the rise of Saddam Hussein in Iraq dealt another blow to the intellectual’s dream of Arab unity. Iraq lost the war when they invaded Iran and when Hussein invaded Kuwait, the Saudis brought in America to fight off the attack. The impression left on the artists and scholars was that Arabic people were too weak to handle their own affairs and, even worse, members of their own ethnic group couldn’t be trusted or relied upon. A sense of dismay set in.

Ajami also goes into brief details about the Lebanese Civil War in the 1980s. Up until that time, the west end of Beirut was akin to the Left Bank in Paris with chic cafes and the presence of the universities. It was a haven for progressive, upwardly mobile Middle Eastern people. Then the Palestinians invaded southern Lebanon and tried to force the Marontie Christians off their ancestral homeland. The Palestinians lost, but progressed onward to West Beirut and merged with the Iran-backed Hezbollah. West Beirut turned into a ghetto dominated by street gangs of Palestinian and Shia thugs. Anti-intellectualism went on the rise in the Middle East from then on.

Ajami move on to an analysis of Egypt in the eras of Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak. Egypt, along with the rest of the Arabic nations, began a decline into autocratic governments, punishment for intellectuals who challenged their authority, and a rise in anti-Jewish conspiracy theories, political Islam, and Islamic fundamentalism. The lives of Egyptian intellectuals became dampened by governmental persecution and terrorist attacks from fanatical Muslims, some of which were deadly. Ajami is actually quite sympathetic to Sadat, especially because of his efforts to make peace with Israel, but he is also critical of the increasingly totalitarian nature of his government. Ajami has no sympathy at all for Hosni Mubarak.

The final section of this book examines the role that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has in shaping the intellectual life, or I should say the anti-intellectualism, of contemporary Arabic society. While acknowledging the tragic displacement of the Palestinian people, Ajami is also critical of the way Arabs, particularly journalists and Muslim fascists have turned anti-Zionism into their primary ideology since the 1990s. He points out that Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin did everything they could to make peace with their neighbors, most of which, like the Jordanian royal family and the Egyptian government, had a low opinion of the Palestinians from the start, even laying claim to the land that is now owned by Israel. There was a time when Jordan claimed Palestine as their own territory and even denied that Palestinians had a right to their own nationality. Ajami also points out how Arabs turned against their leaders like Sadat and both King Abdullahs from Jordan for trying to make peace with Israel. He even points out how much Arabs hated Yasser Arafat for agreeing to the current borders of Gaza and the West Bank in a pragmatic attempt to prevent further wars with Israel. But the fascisitc elements in the Middle East got their way and the result has been a never ending cycle of attack and counter-attack in the so-called Holy Land ever since.

Fouad Ajami’s whole concept of The Dream Palace Of the Arabs is that Arabic intellectuals have been chasing after utopian solutions to their problems. When one naive ideology fails they move on to another naive ideology. Now these intellectuals have run out of ideologies and a lot of the poets have degenerated into writing vicious screeds against the Jews or retreating into a comforting and toothless womb of sentimental love poetry with no political ambition at all. Ajami’s writing is roundabout and never direct, but if you follow his argument carefully, you realize he is making an argument pragmatism. That means working with what you have within the realms of the possible. Arabs might not like the political choices they have, but if they are the only choices it is wise to do the best with what is there. Progress only happens in stages anyways. No savior or messiah is going to come and put eveything in order. No war is ever going to create stability or independence.

After living in the Middle East, I can supplement Ajami’s argument with my own observations regarding the anti-Jewish rhetoric and conspiracy theories that run rampant in the region. Arabic people have legitimate grievances against their autocratic governments, but censorship is heavy and criticizing their leaders is extremely dangerous. It is my contention that these politicians encourage the hatred of Jewish people and Israelis as a valve for releasing psychological pressures resulting from frustrated political desires while at the same time serving as a deflection away from the governments that are the actual source of people’s anger. It’s better for the government if people hate the Jews rather than the politicians. The unintended consequence is that instead of endangering the stability of Israel, the stability of the entire world is at risk due to radicalization and terrorism in the Arabian lands.

Fouad Ajami has a compelling perspective on the Arab intellectual and Arabic society in general. The worst thing I have to say about this book is that his indirect style of making an argument can be frustrating for the reader at times. While he has a definite point to prove, he never states it clearly and directly so that the effect is a kind of wishy-washy dance around what he wants to say. That indirect style may be the result of living under a repressive political regime, but then again it may just be the way people communicate in the Middle East, or maybe it is a little of both. There are also times when he includes references to literary works by Arabic authors simply because they are known outside the Middle East and not necessarily because their works lend anything of immediate value to Ajami’s thesis.

The Dream Palace Of the Arabs may not arrive at the conclusion that Arabic people want to hear. I imagine some people will uncritically hate this book simply because Fouad Ajami wants Arabs to have peaceful relations with Israel whereas he sees that politicians and journalists are making the situation worse for Palestinians, not better. I think what he has to say should be heard because the wars in the Middle East are resulting, so far, in nothing but eternal warfare. Simply put, Ajami is saying that Arabs need to get their feet on the ground, get their heads out of the clouds, overthrow the dictators, and come up with a better way to solve problems. It is a bitter pill for some to swallow, if they even bother to swallow it, but it is something that needs to be said anyhow.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Novelist Interview - Chuck Palahniuk

by Soft White Underbelly

#chuck palahniuk#soft white underbelly#transgressive fiction#authors#postmodernism#american literature#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes