Text

Hope in the Face of Heartbreak

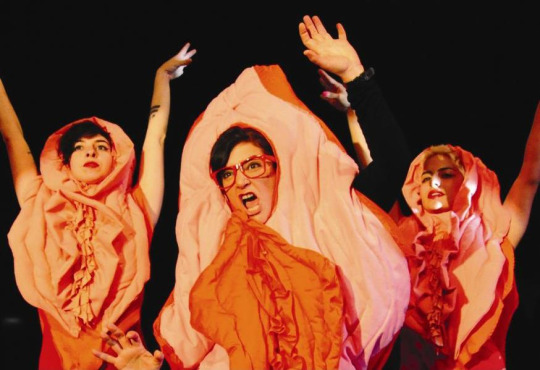

This essay was given at a lecture for the launch of the Women and Gender Studies Institute PhD program at the University of Toronto. Muñoz discusses identity knowledges from Robyn Wiegman’s Object Lessons to foray into whether or not there is “credible hope” in the objects we fee, if they can continue to replenish us (208). He ties this back to his previous chapter’s theory on incommensurability, particularly through an analysis of Anna Margarita Albelo’s film Who’s Afraid of Vagina Wolf. He argues that there is an “incommensurability between fields of knowledge production and the real social contests they call upon and count as their galvanizing objects” (209). He explains the Albelo film in depth, and turns to the zany (and connects to Object Lessons) to extend that despite the lack of ideal situations present in these texts, they represent a strong sense of hopefulness, a manifestation of the incommensurable, which he connects to his oft-used Blochian framework.

from Albelo’s Who’s Afraid of Vagina Wolf

0 notes

Text

Race, Sex, and the Incommensurate

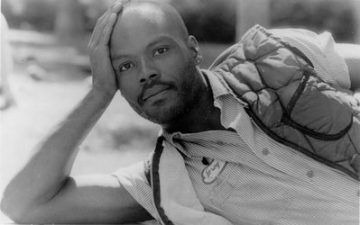

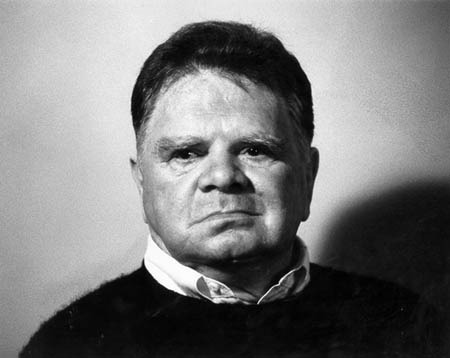

Gary Fisher with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick

In this essay, Muñoz seeks to answer how queer politics might exist despite his claim of queerness being not-yet-here. He looks at Sedgwick and Fisher’s collaboration through the former’s editing of the latter’s posthumous creative work. He brings back his commentary on gay assimilation, stating that “the call for rights and the concerns about personal and collective value... have been critiqued... as often displaying homonationalist tendencies” (194). He hails Jean-Luc Nancy to explain the “unquantifiable integer” past the political which becomes a “sharing (out)” (194). Muñoz explains what he sees to be the difference/issue between “queer” and “queer of color” politics. He describes the UNC-Chapel Hill, returning to his previous mentions about public sex, to express how Fisher wrote about sex to write about representation. Muñoz returns to Nancy’s ‘being singular plural’ to extend a theory of knowing in truth, which manifests in the relationship between Fisher and Sedgwick. He talks about reconstruction, particularly through Klein’s notion of the reparative, and how he finds this notion productive, both as a collective reparative and an individual one. He discusses the narrator in Fisher’s work, and usefully mentions that racial fetishistic erotics are still deeply tied to systemic racism. He delineates his concept of common communism through the singular plural, and that it precedes the political. Muñoz says that there is a commonality to the incommensurable, and that these commons also recognize the violent nature of the collisions of being singular. He extends that Fisher’s life is “a testament to the very limits of understanding his life as a black gay man solely through politics” (205).

Gary Fisher

0 notes

Text

Conclusion

“Take Ecstasy with Me”

Muñoz approaches the conclusion with this line from the band Magnetic Fields, who ask for a “stepping out” from their audience (185). He connects their interpellation of ecstasy with the religious ecstasy observed in the marble sculpture of Saint Theresa, the Greek ekstasis, and Heidegger’s ekstatisch. He extends that to take ecstasy is to step out of straight time. He analyzes the lyrics to the song as well as Elizabeth Bishop’s poem, Invitation to Miss Marianne Moore. Muñoz specifically looks at the concepts of queerness in flight and in the bridge in Bishop’s work, and connects them to both lesbionic material and strains of bridges in other queer work. Ultimately, Muñoz says that his text can “be read as an invitation, a performative provocation” to consider queerness in its “aesthetic and political practices” and to arrive, hopefully, “at collective potentiality” (189).

the band Magnetic Fields

0 notes

Text

After Jack

Queer Failure, Queer Virtuosity

Muñoz hails Jack Smith as “the progenitor of queer utopian aesthetics” (169). He clarifies disidentification and connects it to Smith’s work. He describes Smith’s manifesto “Capitalism of Lotusland” to extend that Smith’s challenging and restructuring of capitalism and private property through fantasy is queer utopia. He explains how Smith challenges careerism, and applies this concept to “the current problem of gay and lesbian neoliberalism” such as the Human Rights Campaign (172). He recommends that we reframe escape as not merely a surrender, but rather a refusal to be complicit in dominant institutions. He frames queer failure as this type of escape, that is also entwined with virtuosity.

-dynasty handbag and the strange itinerant beauty of queer failure-

Muñoz explains that Smith runs counter to overarching concepts of the ‘normal,’ and in doing so rejects straight time, because queerness is destined to fail in the rigid temporality of straightness. Muñoz introduces the persona and performances of Dynasty Handbag, and believes that the failures that the character experiences “work as political refusal” (176). He extends the Italian Virno’s support of Operaismo, which opposes work at its core through exodus, and how this reimagining of escape provides an act of social transformation.

-the anticipatory illumination of queer virtuosity-

Again, Muñoz turns to Virno to establish that virtuosity also serves as a form of escape. He explains the group My Barbarian and their performance of Pagan Rights, which expresses pagan demands that he connects to queer utopia. He also studies The Golden Age and its questioning of European imperialism, that interpellates the audience to embody the message of colonization.

-kalup is waiting-

Muñoz sees Kalup Linzy as a conflation of failure and virtuosity. He looks at Nyong’o’s analysis of Linzy’s work as Deleuzean masochism, stating that it represents his concept of longing expressed throughout Cruising Utopia. He explains that “there is something queer, Latino, and transgender about waiting,” that minoritized people experience waiting because they have been cast away from straight time and also because they have created their own time (182).

vimeo

My Barbarian, Pagan Rights, 2006

youtube

Kalup Linzy, Sweetberry Sonnet, 2008

1 note

·

View note

Text

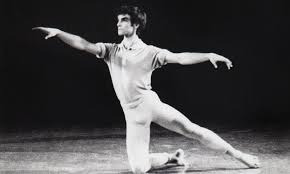

A Jeté Out the Window

Fred Herko’s Incandescent Illumination

Muñoz explains that while surplus value has a capitalist function in the economic sense, it comes to mean that which functions beyond capitalism when considered in the aesthetic sense. He sees that Fred Herko’s work in choreography is one of surplus that contains utopian traces. After Herko’s suicide, Muñoz sees that the traces (”different lines of thought, aesthetics, and political reverberations” (148)) left by Herko are queer because his suicide resonates “beyond traditional notions of finitude” and his traces are marked by the aforementioned ephemeral qualities of queerness (see Ghosts) (149). Muñoz believes that Herko’s campiness indicates Bloch’s preference for the (queer) ornamental over functional form, and looks at this through Herko’s dancing with the Judson Memorial Church and in the Summers’ film Fragments (Judson Dance). He also looks through the lenses of Banes and Johnson. Muñoz warns that rather than look at Herko’s speed-absorbed life with pity, we might instead understand that this life is striving for utopia. He clarifies that the “history of actually realized utopian enclaves is, from a dominant perspective, a history of failures” (155). I find his statement of dominant perspective to be most useful in this section of commentary, where Muñoz says that queer failure may in fact be utopic. He discusses di Prima’s commentary of Herko being “off course” in her poem, and Herko’s acting in three Warhol films. Muñoz returns to Agamben’s gestural to clarify that it “is not a full-fledged resistance, but it is a moment when that... spatial and temporal order that is calibrated against one, is resisted” (162). Using Marcuse and Bloch, he argues that movement is essential to queer utopian expression “because it enables a mode of cognition” that is detached from the negative qualities inherent to the aforementioned performance principle (166). He ends by describing his personal stories connected to suicide and his lament for Herko’s death.

youtube

Mozart Coronation Mass in C Major

Fred Herko

0 notes

Text

Just Like Heaven

Queer Utopian Art and the Aesthetic Dimension

Muñoz begins with a tale of his distaste for camouflage because of its ideological representations to shift into his central focus of the queer aesthetic dimension.

-queer aesthetics as ‘great refusal’-

Muñoz describes Marcuse’s ‘performance principle’ from his 1995 Eros and Civilization. This term refers to “a formulation that describes the conditions of alienated labor that modern man endures” (133) which challenges “normal love that keeps a repressive social order in place” (134). The performance principle is one of three (the other two being the pleasure and reality principles). Marcuse uses the term to observe the tragic tales of Narcissus and Orpheus to extend that the negative connotations attached to them reveal the (queer) potential of a different reality. Muñoz uses this to extend that queerness, more than sexuality, reflects a refusal to fall into societally mandated preestabilshed functions.

-the dance of silver clouds-

Muñoz sees Warhol’s Silver Clouds as a Narcissistic gaze which interrupts the performance principle as an expression of portraiture in placing the audience member in a reflection within the stage/performance. He sees that their form as pillows presents them as holding both rest and play to challenge the “coercive work ethic” mandated by the performance principle (138), and that because they are suspended and not reachable, they represent an unrealistic Narcissistic desire. Muñoz transitions to camouflage to express how the expectations of camo are transformed by Warhol in a queer fashion because “queer aesthetics... call the natural into question” (138). Hodges does the same as he incorporates a new sensation of perspective and animation to camo in his painting... Muñoz sees utopia in the horizon implicated by the painting.

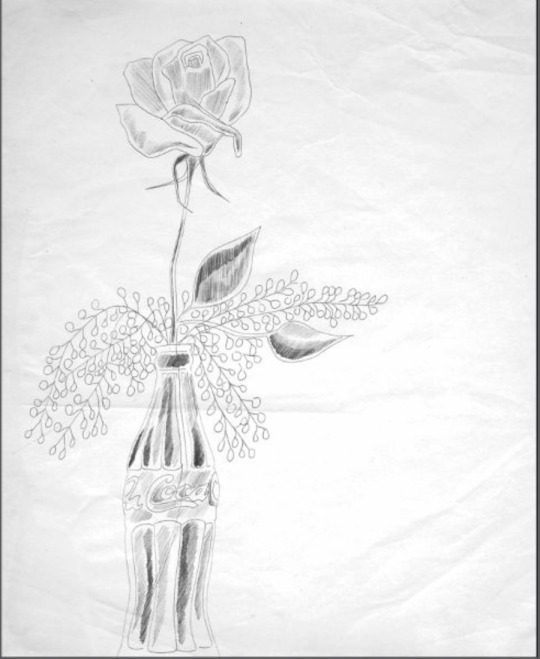

-landscapes of ornamentation-

Muñoz explains Hodges’ view that landscape art represents a utopic world. He views the utopic throughout several of Hodges’ art pieces in varying levels of depth, as well as the work of contemporary Félix González-Torres. He continues by demonstrating that the homoerotic ornamentation in Warhol’s work suggests a queer daydreaming, that, again, challenges the performance principle. Muñoz then hails back to his discussion of Warhol’s drawing of a flower in a Coke bottle that he first mentioned in the book’s introduction, now mentioning its Narcissistic reference. He believes that for these artists, the utopian exists in the otherwise commodified ‘everyday’ objects that they turn queer. He finishes by claiming that gay liberation has become, in contemporary times, increasingly assimilationist, and thus more in line with the performance principle than with its original ideologies.

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, 1986

Jim Hodges, Oh Great Terrain, 2002

0 notes

Text

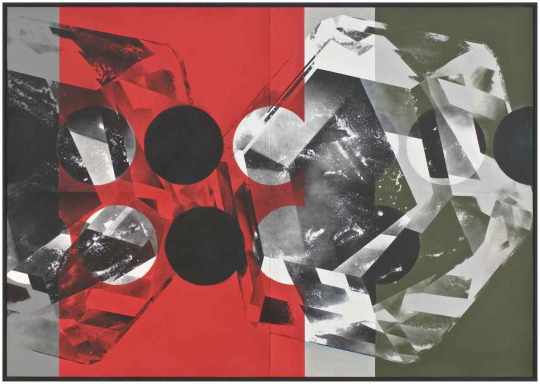

Utopia’s Seating Chart

Ray Johnson, Jill Johnston, and Queer Intermedia as System

In this chapter, Muñoz turns to avant-garde cultural work during the Stonewall period (1970s) to establish an “intermedia approach” (116) to the concept of queer utopia. He describes the artist Ray Johnson and his work through the New York Correspondence School, saying that Johnson would misspell it as correspondance (like Derrida’s differance, almost) to suggest its performance. He would send out all types of unexpected mailings, such as Moticos collages, and ask for responses. Muñoz acknowledges that his prose resembles the associative qualities of Johnson’s correspondence, and continues to articulate his personal, associative connection to Johnson’s work. He establishes that Johnson’s work is utopian because it rejects ‘objective realities’ of temporal, spatial, and ontological conventional understandings, before turning to critic Jill Johnston. He looks at Johnston’s writing through dance of Rainer to connect them both with Johnson, all of which to say that “everything corresponds to everything” (121). Muñoz does this to theorize a queer kinship, circuit, or system in contrast to traditional forms or structures of connection or belonging. He connects this to his main theoretical framework of Bloch to say that utopia works both by negation (critique) and positive valence (projection forward, futurity) (125), an example of which may be seen in his portrayal of a letter’s life through the NYCS, where rather than simply lie in the “’here to there’ trajectory” of a ‘normal’ letter’s life (negation), it rather becomes transformed continuously as it is passed between friends and acquaintances, which makes it into a form of queer futurity (positive valence) (126-7). He continues with examples of Luke Dowd’s artwork (diamonds, koi fish, Silver Surfer), who he feels connected through a queer network, to establish that he feels like he has a place at the NYCS table through his association.

Luke Dowd, untitled, 2007

0 notes

Text

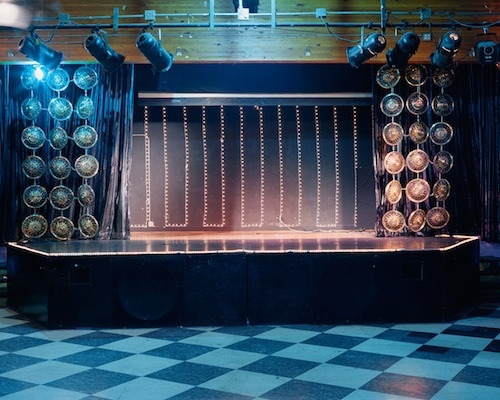

Stages

Queers, Punks, and the Utopian Performance

-utopian performatives-

In this chapter, Muñoz approaches the concept of staging as a reclaiming of the term from heteronormative parents to look at punk rock and queer staging through the lens of utopia. He acknowledge’s Peggy Phelan’s work in performance but challenges it by saying that performance can be reproduced, in a materialist fashion. He details the difference between possibilities and potentialities, as seen through Agamben and Derrida. He discusses how a focus on Agamben’s “means without an end” is utopian because it “interrupt[s] aesthetics and politics that aspire toward totality” (100). He details his history with artist Kevin McCarty and explains why he believes it is so important that “queer intimacies” (ie his relationships w the people he studies) exist. He says the power in McCarty’s “Catch One” lies in its possibility. Muñoz believes that the performance of amateurism, in being an in-process work, a “refusal of mastery,” insist on the “becoming” of queer futurity (106). He says that McCarty’s work represents a stage where “potentiality, hope, and the future could be, should be, and would be enacted” (113).

“Catch One” by Kevin McCarty

0 notes

Text

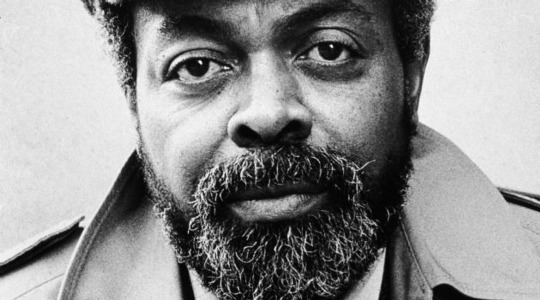

Cruising the Toilet

LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka, Radical Black Traditions, and Queer Futurity

Muñoz explores Baraka’s 1964 The Toilet to interrupt “straight time and the temporal strictures it enacts” (83). He hails Moten’s In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition for its perspective on black aesthetic practices. He uses Anzalúa’s jotería to claim that “avant-garde aesthetics underplay both explicitly queer presences and... racialized participation, labor, and influence” (84). He quotes Joe LeSeuer’s (O’Hara’s roommate) racist passage about Jones to enter an analysis about Jones’ complicated identity as a black writer who was both married to a woman and engaged in homosexual activity. Muñoz uses Moten’s homosexual-interracial seizure and connects Robinson’s pre-Marxist temporality to Bloch’s temporality. Muñoz tells us that the “scene direction [in The Toilet] is the play’s choreography of the gestural” (88) in a choreographic manner, and uses Agamben to clarify that in referring to gesture, “nothing is being produced or acted, but something is being endured and supported” (91). He agrees with Edelman’s focus on queer negation, but challenges a strict notion of queer jouissance through Butler’s concept of recognition through vulnerability to establish his analysis of The Toilet as one based in recognition to establish a queer futurity. This is for the purpose of challenging antirelationality that is dominant in queer criticism. Muñoz seems to acknowledge that while scholars (Edelman in particular) are doing important work in queerness, they often fail to recognize intersectionality in their critiques (such as Edelman’s inability to acknowledge blackness in his criticism of “A Parent’s Bill of Rights”). Muñoz notices the irony in Baraka’s activist support of queer identities after his daughter’s death despite his earlier denouncement of queerness following The Toilet, and uses these three events (including the transphobic murder of Sakia Gunn) to frame his assertion that the dominant futurity of children is one that privileges always already white children, and thus it is necessary to conceive a utopia where queer children of color may also grow up, to challenge the establishment of strictly white heterosexual futures.

Baraka/Jones

0 notes

Text

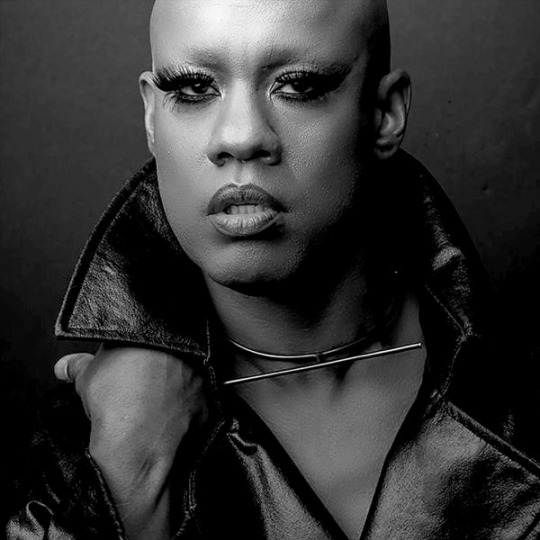

Gesture, Ephemera, and Queer Feeling

Approaching Kevin Aviance

Muñoz believes that we must understand queer evidence as tied to ephemera (”the remains that are often embedded in queer acts”) in the expression of gesture (”a refusal of a certain kind of finitude”) (65). He believes that dance is a key form of expression, a performed gesture that expresses queer possibilities. In this gestural analysis, he believes the performance of Kevin Aviance to be key, while considering the work of Paul Siegel on queer dance and Paul Franklin on Charlie Chaplin.

-beginning one: memory-

Muñoz details a lovely personal story, stating that he considers it (as well as the camp aesthetic of Justin Bond’s Kiki) as a form of ephemeral proof. He analyzes Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” as an expression of ephemeral memory, one that suggests that there is a queer trace in the intent to be lost. Muñoz suggests that “to accept loss is to accept queerness... the loss of heteronormativity” (73).

-a body: approaching aviance-

Muñoz turns more concretely to Aviance, who is said to be widely known and very important to his queer audiences in NYC. Muñoz says that Aviance incorporates aspects of both pain and pleasure in his gestures, as they are not binary in queerness. Aviance’s performances insist on blackness and a queerness that challenges traditions of gay white male performances. Rather than imitating womanhood, they seek to approximate a more broad “notion of femininity” (76). Aviance embodies a gender hybridity in which masculine, feminine, and even robotic movements constitute his gender expression, to challenge femmephobic or otherwise masculine-centered gay clubs (”he is the bride between quotidian nightlife dancing and theatrical performance”) (77). Aviance’s multiplicity of gender mean that he does not fall within Marxist commodity fetishes, and rather embodies the gestures that his audiences themselves cannot express. Muñoz compares Aviance’s gestures to WEB Dubois’ sorrow songs in The Souls of Black Folk to say that there is something else underlying what we see--here, the power of “racialized self-enactment in the face of overarching opposition” (80).

-conclusion: the not-vanishing point-

Muñoz ends by extending that dance is an act that vanishes as it materializes, and in queer dance, this ephemerality manifests as a form of queer evidence, contrary to the logic of heterosexuality.

Kevin Aviance

0 notes

Text

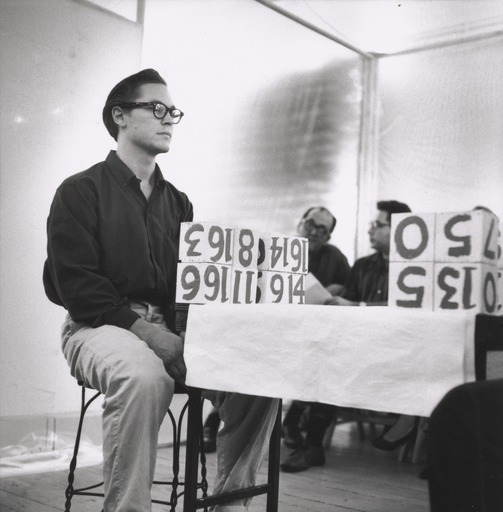

The Future Is in the Present

Sexual Avant-Gardes and the Performance of Utopia

Muñoz says that while heterosexual culture depends on a “deferred future,” queer individuals must not be complicit in the binary of present and future and rather see “a future in the present” following CLR James. He stresses performativity in “anticipatory illumination of a queer world.” (49)

-the past for the future: queer happenings-

Muñoz begins with Delany’s The Motion of Light in Water to evoke avant-garde performances that create new social formations. These performances are an interaction with Kaprow’s “Eighteen Happenings in Six Parts, the silent gay sexual acts during the night at trucks by the river on Christopher Street, and the well-lit St. Mark’s Baths. “Public sex culture revealed the existence of a queer world, and Kaprow’s happening explained the ways in which such utopian visions were continuously distorted” accurately demonstrates Muñoz’s position of Delany’s experience of utopia through gay public sex acts (51). He says that he uses Delany to shed light on current attacks “on cultures of sexual dissidence” in NYC (51) through Mayor Giuliani’s rezoning of public sex outside of the city (which largely fragmented queer spaces). Muñoz rightly recognizes that the industries impacted by Giuliani/Bloomberg policies (street vendors, taxi drivers, and sex workers) “are heavily populated by people of color” (53). Delany’s concept of “contact relations” is used to frame public sex as a place for important “interclass contact and communication conducted in a mode of good will” which Muñoz says is being replaced by “basic [classed] networking” through the “late Disneyfication” in Times Square (53). He says that by removing queer commercial sex venues and replacing them with chain restaurants and corporate venues, Giuliani has created an environment where upper middle-class [whites] are largely unable to make meaningful contact with anyone outside of their class (ie, largely queers and POC). Muñoz says this is a symptom of Duggan’s concept of homonormativity, explained through Adorno’s “on and off” sexuality (”as long as sexuality is bridled, it is tolerated”) (54). Muñoz continues by looking at CLR James’ The Future in the Present and Facing Reality. While recognizing that James’ statement that socialism already exists and must simply be seen has been widely critiqued, he finds that his idea that “minoritarian citizen-subjects who contest the majoritarian public sphere” allows us to find “world-making potentialities” (56).

-magic touches: queers of color and alternative economies-

Muñoz describes Magic Touch (a closed bar in Jackson Heights, Queens) and the Gaiety (a closed bar in Manhattan). He credits the survival of Gaiety to its incorporation of state ideologies before the state formally instituted them as policies (namely disallowing sex and employing white, muscled gays) that fed into dominant modes of inacess and desire that “can be characterized as primarily being about privatized networking relations” (57). He contrasts this to Magic Touch, where the majority of performers were Latino or African-American, the dancing was in a sexual hip-hop style, and the performers mingled with audience members freely. While there were erect dancers at Gaiety, Magic Touch would be closed down if the dancers were nude. Muñoz suggests that the interracial and inter-class qualities of hustler-john interactions at Magic Touch usurp “naturalized performances” within the heteronormative and capitalist sex trade (59). He mentions that this is only allowed (by the state) in industrialized and isolated spaces that put gay men at higher risk.

-stickering the future-

Muñoz describes the stickers produced by the un-named collective referred occasionally as f.a.g. (feminist action group) or SADD (sex activists against demonization) that consistently uses a Mickey Mouse head to represent the control of dominant commercial industries. Muñoz argues that the stickers are a place of public social interaction where sexual norms are being called into question, making them a place of avant-garde sexual performance.

-mourning through militancy: matthew shepard and others-

Muñoz explains how an NYC vigil in response to the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard is demonstrative of the state’s reaction to queer masses. He says that the police brutality in response to what was “supposed to be a somber political vigil” (63) shows how the state is scared of a mass queer uprising and thus had to respond by fragmenting, hurting, and separating the queer mass at the vigil--”the utopian promise of our public performance was responded to with shattering force” (64).

-making utopia-

Muñoz summarizes that his concept of anticipatory illumination should be held as important to criticism that considers Adorno’s concept of determined negation in utopia.

from Kaprow’s “Eighteen Happenings in Six Parts”

0 notes

Text

Ghosts of Public Sex

Utopian Longings, Queer Memories

-witnessing-

A talk by Douglas Crimp extends that the intense death toll of AIDS created not only a loss of lives but also a loss of queer sexual spaces and practices. Muñoz shows us that many of the practices Crimp cited as lost (or more accurately, mourned) are continued by gay/queer individuals; this, and, Crimp’s connection to Freud’s mourning of liberty, makes Crimp’s talk utopic. Muñoz criticizes Bersani’s “Is the Rectum a Grave?” by citing how his antirelationality, while useful in its subversion of previous queer theories, ultimately critiques coalition politics, separating ‘always-white’ gay men and ‘always-straight” POC. Muñoz tells us that this chapter will focus on queer utopian memory, through gay male cultural works (largely about AIDS/HIV).

-fucking,remembering-

John Giorno’s spontaneous sex with Keith Haring is presented as a type of queer world-making in the present through the process of memory. Muñoz uses Adorno and Bloch to introduce the concept of determined negation. By analyzing Giorno’s intensely sexual passages during the AIDS epidemic and his subsequent “shock” at the outside heteronormative world through Adorno’s “casting a picture,” Muñoz tells us that Giorno is presenting a sexual utopia that challenges the current AIDS crisis while imagining a sexual present with a potential for disaster by AIDS--Giorno’s sexual freedom is a type of utopia.

-ghosts-

Tony Just’s 1994 project demonstrates Muñoz’s “ghosts of public sex” through the ghostly quality of his photographs of sanitized men’s rooms, which represents the affective intergenerational haunting of gay men following the AIDS crisis. He uses Raymond William’s structure of feeling as his theoretic framing for such an analysis. Muñoz explains that Derrida’s hauntology is important in situating public sex. He ends by reading Just’s work through Bloch’s Traces to signify a desired collectivity.

-situating-

Muñoz seems to argue that the ghostliness of public sex is a performance of illicit/illegitimate gay activities (related to AIDS) that allows those who partake in ‘legitimate’ activities to create a notion of what the “sanitized gay world” should look like (46). He says that ghost theory disrupts a binary between those who do and do not have HIV by no longer forcing them to ‘come out’ with their status or to otherwise further ostracize men with AIDS by focusing on those who do not have HIV.

Tony Just, 1994

0 notes

Text

Queerness as Horizon

Utopian Hermeneutics in the Face of Gay Pragmatism

Muñoz begins by establishing that Bloch’s “no-longer-conscious” offers an entrance into utopian desire. He uses an exploration into the manifesto of the Third World Gay Revolution to extend that the forms of thinking and activism he seeks to create discourse on have longevity--they’re a long time coming.

He continues by establishing a collective “we,” stating that it is a concept that is forever in flux, and one that goes beyond the simplicity of identity politics (what Muñoz calls “particularities”). Ultimately, this is to say that belonging in collectivity = the field of utopian possibility, which contains multiple forms of belonging (multiplicity of “we,” 20).

Muñoz criticizes Evan Wolfson’s limited and assimilationist viewpoints as contrary to freedom and liberation, to establish a critique on “gay pragmatic thought” (21) that he continues by referencing Biddy Martin and establishing a contrast between gay pragmatism and idealism. He seeks to explore idealism, particularly through the not-quite-conscious and the no-longer-conscious. He extends that queerness has not yet arrived.

Muñoz says that the potentiality of queerness (drawn from Bloch’s Principle) challenges the “autonaturalizing temporality that we might call ‘straight time’” (21). He encourages us to use Husserl’s horizons of being and Barthes’ mark of the quotidian to understand queerness. He extends this to us by analyzing Schuyler’s “A photograph” where he uses Schuyler’s “ecstasies” to represent queer relational futurities, which to Muñoz recalls the work of Heidegger in Being and Time. Ultimately, Muñoz criticizes the linearity of straight time, and uses Schuyler to say that the phenomenological questioning of straight time is “the fundamental value of a queer utopian hermeneutics” (25). Muñoz identifies this as the utopian impulse.

He continues by saying that performativity and utopia both challenge the epistemological (what we consider “justified belief”) to discover what is to exist in futurity. He clarifies that the no-longer-conscious does not equal regular historical analysis, but rather it is a critical analysis of the past through the lens of what may happen in the future. To me, Muñoz appears to say that to historicize in the classical sense is to maintain the “normalcy” of heteronormative approaches, and so to queer the no-longer-conscious, it must not follow the “evidencing protocols” of the “normative” (27). He also believes we must look at the present through the lens of the past and the future.

I understand the no-longer-conscious much better once Muñoz compares it to Derrida’s trace. Muñoz says that queer utopian hermeneutics are best encapsulated through the “epistemologically and ontologically humble” and the addition of the affective to a cultural surplus (28) In terms of spatialization, Muñoz believes that while the present is “provincial,” the past and future must call towards globalization, positing that they represent a wider “then” that enacts on the more restricted “now” (as a combination of temporality and spatialization, it would seem) (29).

The no-longer-conscious is not an abstract utopia, Muñoz warns. He tells us that while Bloch’s separation of rationalism from universalism signifies a turn towards the idealistic rather than the pragmatic, we must recognize that the no-longer-conscious leads us to a not-yet-here (yet appears to be the key word here). He criticizes Harvey’s intense claim that to explore sexuality is to be bourgeois, which to me seems to be about Harvey’s inability to consider intersectionality (31). This is to say that white gays/lesbians avoid race or ethnicity, and white (neoliberal) Marxists avoid sexuality and gender, which are both products of pragmatic and antiutopian thoughts.

Muñoz ends by saying that performing futurity is the ideal way to queerness.

an image of Schuyler

0 notes

Text

Introduction: Feeling Utopia

José Esteban Muñoz begins this text by explaining that he perceives queerness to be an ideal that we seek to achieve rather than something we “are” or something that “is.” It is to be found in the future, to be reached for from the limitations of the past and the present. Muñoz suggests that aestheticism is the manner in which we achieve futurity; he explains that the queer aesthetic is used to “map social relations” and that it is a “performance” as a “rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world” (40).

Muñoz borrows from Kant and Hegel in his thinking, as well as the Frankfurt School in terms of Marxist utopianism, yet credits his strongest thinking to Bloch’s “The Principle of Hope,” where the philosopher discusses the concept of utopia quite deeply. Muñoz dismisses Bloch’s questionable perspective on queerness as he posits to use Bloch’s theory to open a new mode of queer thinking--that of idealism. Quite usefully, Muñoz explains how he hopes to explore Bloch’s idea of “concrete utopias” that he historically places around the Stonewall riot in 1969 (43-44). He also uses associative and personal work in his study.

Muñoz places special importances in Bloch’s contemplation (and astonishment) as he looks at Warhol and O’Hara as introductory examples of his queer utopianism (beginning in 47) because they offer an ‘out’ to Bloch’s “darkness of the lived instant” (48) through their (seemingly performative) happiness. He specifically looks at Warhol’s Coke Bottle and O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You” (links below). Muñoz seems very invested in the quotidian and its manifestations as queer utopianism, as he says “Both queer cultural workers are able to detect an opening and indeterminacy in what for many people is a locked-down dead commodity" (53).

He continues by mentioning Austin’s concept of the felicitous and its inability to be fulfilled (are we really doing something by saying something? what are the implications of the act of speech? etc). Muñoz clarifies that he seeks to challenge political idealism, the “antiutopian” sentiment, and the “antirelational” (57-8). He seeks to engage in queer social relations. He mentions Nancy’s concept of the singular plural and uses it to extend the idea that queerness as ontology might only be understood if it is simultaneously conceptualized as both relational and antirelational. In particular, he believes that Bersani and Edelman’s antirelationalisms are useful in his work, where he says that “My argument is therefore interested in critiquing the ontological certitude that I understand to be partnered with the politics of presentist and pragmatic contemporary gay identity” (60).

He continues by mentioning more scholars and their relevant theories, such as Sedgwick’s Reparative hermeneutics, Virno’s modality of the possible, Felman’s radical negativity, and Jameson’s anti-antiutopianism. In his subsequent exploration of Eileen Myles’ Chelsea Girls, Muñoz further extends the argument he began with O’Hara and Warhol’s quotidian Cokes--Myles’ quotidian service actions with Schuyler, in Muñoz’ analysis, solidifies the notion that this queer relationality is transformed by a potential futurity.

He smartly recognizes his critiques (such as using Bloch over Benjamin, or not considering Foucault’s History of Sexuality as usurping Marcuse) and mentions that he has made his theoretic decisions so as to focus on scholarship outside of what is currently popular or well-read in queer studies. He then contextualizes Marcuse’s relationship with Heidegger, and mentions more theorists (Halberstam, Freccero, Freeman, Dinshaw, Gopinath, Dolan, Berlant). He mentions that his work lies solidly in the realms of queer feminist and queer of color forms of thinking. Ultimately, Muñoz tells us that he hopes to reformat our conceptions of utopia and approach queerness through this fresh lens.

(some) Important Texts that Muñoz mentions:

Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope, 3 vols., trans. Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995).

Jill Dolan, Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005).

Frank O’Hara, Having a Coke with You (click title to access link)

Andy Warhol, Coke Bottle (click title to access link)

Andy Warhol, Still-Life (Flowers) (below)

J.L. Austin, How to Do Things With Words.“(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962).

Leo Bersani, Homos (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004).

Muñoz is clearly well-situated in his exploration of queerness and performativity though critical theory. He must mention about twenty theorists/theories (that do provide an excellent framework and a pot for future reading, I might add). This introduction seems most useful as a contextualization of his utopian theory, explaining his approach to queerness in Cruising Utopia. Personally, what I find most important is his notion that futurity comes from the quotidian--queerness is seemingly implicated in the transformation of the quotidian into an act of being, or of identity. This suggests that queerness is a complex, deep inaction of being. As I keep reading, I will keep Muñoz’ strong leaning on Bloch as the center theory on my mind, while considering how elements of the quotidian enter his explorations.

0 notes