Text

Notes on “Diversity”.

Following the brutal murder of George Floyd in 2020 – a spark that ignited riots in protest of police brutality and, in turn, the inequality that Black people face on a daily basis – fashion was forced to reckon with its own shortcomings, as an industry that has long neglected people of colour across the board.

Amid a sea of black squares – allegedly posted in solidarity with Black people, though you’d struggle to find one to corroborate this – brands and publications scrambled to atone, not knowing whether to apologise for the existence of systemic racism or fashion’s part in upholding it (see: here, here, and here). All the while, promises were made for a better, more inclusive future.

Yet, almost three years later, all is quiet on the fashion front with diversity and inclusion seemingly no longer a priority – the industry’s short attention span quickly moving on now it’s no longer en vogue.

Last June, The British Fashion Council released its ‘Diversity and Inclusion in the Fashion Industry’ report, revealing that only half (51 per cent) of the 100 companies interviewed had implemented D&I initiatives, with even fewer dedicating budget towards those efforts. It’s disappointing, even more so to learn that those hired to implement D&I strategies often leave their roles swiftly as has been the case at Gucci and Nike.

The report is reflective of fashion’s attitude towards diversity – with mostly white voices echoing familiar platitudes around ‘learning’ and ‘growing’, reluctant in committing to tangible targets. While quantifying representation isn’t necessarily helpful in moving towards genuine diversity and inclusion, fashion’s longstanding ability to champion exclusivity and use ‘taste’ and networking culture as gatekeeping tools warrants numerical evidence to highlight its abysmal efforts.

Though, even this in itself is a troublesome task as the New York Times found in its own 2021 report on Black representation in fashion, with several European companies citing legislation such as GDPR as an obstruction for gathering and sharing data on their failings. As the BFC found, even after 2020’s demand for diversity, people of colour currently make up only 5 per cent of employees at a direct report level – hindering any growth in representation in leadership roles.

instagram

Until now, Black creatives have had to go it alone, relying on their excellence to be noticed – shining so bright, it’s impossible to dim. The door, now slightly ajar, has made way for a number of rising stars, more often than not ‘firsts’ in their roles or achieving feats that previously weren’t attainable for people of colour.

From Gabriella Karefa-Johnson (the first and only Black woman to style a Vogue cover) to Tyler Mitchell (the first Black photographer to shoot a Vogue cover), others include Elle UK’s Kenya Hunt, The Cut’s Lindsay Peoples, Harper’s Bazaar’s Samira Nasr, and Rafael Pavarotti.

Ib Kamara best exemplifies this calibre of creative – a talent so in-demand, it’s a wonder when he sleeps, juggling roles as Dazed’s editor-in-chief, Off-White’s art and image director, as well as working as a freelance stylist for Chanel, Vogue, and H&M.

While working twice as hard to get half as far is a familiar mantra for people of colour, the current makeup of the industry sets the bar for them at an almost inhuman level, demanding the very, very best out of them simply to be seen – forgoing the mediocrity sometimes afforded to our white peers. In failing to nurture and recognise talents beyond the brightest and best – i.e. people who were always destined for success on their own volition – brands and publications alike posture as pioneers after simultaneously (read: lazily) box-ticking relevance and representation with such hires.

Yet in some instances, ‘excellence’ isn’t even enough. Pharrell Williams’ recent appointment as Louis Vuitton’s Men’s creative director – succeeding Virgil Abloh (another first) – came as something of a surprise, quelling speculation that the role might instead go to designers such as Martine Rose, Grace Wales Bonner, or Bianca Saunders.

The decision makes sense given the evolving role of a creative director today, with Williams likely chosen for his celebrity status and proximity to the community that Abloh fostered during his tenure, but it’s easy to see why it’s a contentious one. Particularly so, in the case of Wales Bonner, the winner of the LVMH Prize in 2016 – receiving not only a grant of €300,000 to support her business, but more importantly, mentoring from LVMH executives. If not to induct a new generation of designers into the fold, what longevity does the LVMH Prize hope to offer its winners?

Let’s say you’re one of the driven Black creatives who has broken through the proverbial glass ceiling. Surely now, all obstacles limiting your success have been eliminated?

Apparently not.

In the past month, Law Roach shocked the industry with a (now-deleted) announcement of his retirement on Instagram. Arguably the leading celebrity stylist at the height of his career – counting Hunter Schafer, Megan Thee Stallion, and Anne Hathaway among his regular clients, as well as solidifying Zendaya as a fashion icon – netizens speculated that the decision was a cry for attention, prompted by a seating mishap at Louis Vuitton’s Autumn/Winter 2023 show.

Clarifying in an interview with The Cut, the stylist reflected on the industry’s gatekeepers and the hoops he’s still made to jump through 14 years into his career. Even in his candour, it felt as if something was being left unsaid, alluding to the complexity people of colour have in trying to justify the racism they experience to people who will never understand its complexities.

Similarly, Hood By Air co-founder Shayne Oliver recently opened up for the first time about his experience as Helmut Lang’s guest designer in an interview with 032c’s Brenda Weischer. Reflecting on his celebrated single season following the brand’s revival in 2017, Oliver shared his encounters with the brand’s executives. “It was the biggest show they’ve had in 10 years, and the very next day I get notified that I’m not welcome in the showroom in Paris,” he explained.

In examining these somewhat inconspicuous decision-makers more closely, it becomes clearer how people of colour in seemingly senior positions can still find their voices unheard. “The collective intelligence that comes from diverse points of view and the richness of different experiences are crucial to the future of our organisation,” asserted Kering chairman and CEO François-Henri Pinault in June 2020 after Emma Watson, Jean Liu, and Tidjane Thiam were announced as new Board members for the conglomerate. Liu has since resigned and Thiam’s contract completes at the end of 2023, bringing the number of people of colour on the Board back down to zero.

The same is true at LVMH [Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Fendi, Givenchy, Stella McCartney, Loewe, Marc Jacobs, Kenzo, Celine, Off-White], OTB [Diesel, DSquared2, Maison Margiela, MM6, Marni], and Puig [Paco Rabanne, Jean Paul Gaultier, Dries Van Noten, Nina Ricci] while Richemont [Azzedine Alaïa, Chloé, Dunhill] and the Prada group [Prada, Miu Miu] have a single person of colour on their boards, both hired after June 2020. As it stands, none of the above brands have people of colour in the role of CEO.

In 2020, WWD reported on the three Black CEOs in fashion: Virgil Abloh, Jide Zeitlin at Tapestry [Coach, Kate Spade, Stuart Weitzman], and Sean John’s Jeff Tweedy. In the three years since, this number has dropped to zero, following the passing of Abloh, while Zeitlin resigned for a misconduct allegation and Tweedy has left fashion entirely. Interestingly, Chanel is currently the only major house with a person of colour as CEO, after hiring Leena Nair in January 2022.

As the only voice in the room, people of colour often struggle to bring about the radical change needed for true diversity and representation. As Stella Jean found with Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana, despite her continued efforts to bring diversity to Milan Fashion Week’s overwhelmingly white schedule, the arduous battle ended with alleged sabotage and a hunger strike. In response, the CNMI argued their efforts were only possible because of “extraordinary fundings, due to the COVID pandemic”, once again highlighting the reticence to dedicate resources towards D&I and the lack of effort without it.

instagram

2020’s focus on diversity also saw an immediate uptick in Black content – from i-D’s Up + Rising campaign to Hearst’s Black Culture Summit – inviting new writers, photographers, stylists, and more to contribute to titles previously out of reach, though little has changed within most of the teams themselves.

Currently, there are (at least) 16 fashion publications across the UK and US with all-white editorial mastheads – excluding ‘at large’ roles, which people of colour seem more likely to hold since 2020. Extend this to publications with only a single person of colour, often, but not always in the most junior position, and the figure almost doubles.

Unsurprisingly on the flip side, publications with people of colour in the editor-in-chief role – in the UK, British Vogue, Dazed, Elle, Perfect, and Wonderland – translates into more broadly diverse teams inclusive of intersectional identities.

Meanwhile, POC-led publications like Justsmile and Boy.Brother.Friend are stunted in their growth, with both titles appearing to only receive brand support from Burberry during Riccardo Tisci’s tenure as chief creative officer. Though not exclusively a fashion magazine, gal-dem’s recent announcement that it would be shuttering after eight years further highlights the difficulties in creating and maintaining spaces specifically for people of colour.

With limited opportunities in-house and all-white mastheads only commissioning Black freelancers for stories that have a proximity to Blackness – though in some cases, not even then – they’re simultaneously pigeonholed while fighting for the same jobs. A friend, who was recently commissioned and ghosted for a Highsnobiety cover opportunity later found out that (at least) two other women of colour were hired for the same story, the two unsuccessful parties only finding out upon publishing. While this can often be part and parcel of the job, it’s hard to ignore the impact it has on people of colour in instances like this when they’re specifically being hired because of their race due to the nature of the story.

instagram

With the power to bring about change in spaces we rarely occupy out of our hands, it’s up to those in positions of power to go above and beyond in order to rectify previous wrongs.

Amid 2020’s reckoning, Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour apologised via an internal memo in which she admitted her own shortcomings. “I want to say plainly that I know Vogue has not found enough ways to elevate and give space to Black editors, writers, photographers, designers and other creators,” it read in part. While some speculated that this longstanding oversight would signal the end of her 32-year tenure at the helm of the magazine, six months later she was promoted to become Condé Nast’s global chief content editor.

If we’re to see Vogue as the industry standard, Wintour’s efforts since should be heavily scrutinised, a sentiment she agrees with. “I will take full responsibility if the next time you and I speak, there isn't a sense that change has come or is being accomplished, or at least it is moving forward,” she explained to the Washington Post’s Robin Givhan. So, what has been accomplished in the three years since then?

In September 2020, Yashica Olden was hired as Condé Nast’s first global chief diversity and inclusion officer – overseeing a roadmap towards an inclusive future at the group’s various publications [Vogue, Allure, Glamour, GQ, Vanity Fair, etc]. However, a closer look at the three annual Diversity and Inclusion reports for 2020, 2021, and 2022 reveals that the initial marginal growth – +4 per cent total people of colour from 2020-2021 – has since stagnated.

For Black editorial staff specifically, there was an increase of 2 per cent from 2020-2021 with no increase after that, while representation among senior staff has remained the same. In fact, the only constant growth (+5 per cent 2020-2021, +4 per cent 2021-2022) has been for people of colour in the editor-in-chief role, though former Teen Vogue editor (note: not editor-in-chief) Elaine Welteroth shared in her memoir More Than Enough her thorny experiences – alleging her role had different parameters to her white predecessor and that the promotion came with an insulting, non-negotiable pay rise delivered by Wintour herself.

In Condé Nast’s initial D&I report, a commitment was also made to “support diversity among freelancers and contributors, including photographers”, and while there has been a concerted effort since 2020 to bring in new Black photographers who haven’t previously contributed to the publication – names such as Campbell Addy, Joshua Woods, Myles Loftin, and John Edmonds – Asian photographers are still severely overlooked and for almost all, this has been a one-time opportunity.

The same is true for the publication’s hallowed cover. Besides Tyler Mitchell – who was the first Black photographer to achieve the honour in Vogue’s 126-year history – the others who have since joined the hall of fame can be counted on a single hand. That goes for stylists too, other than Gabriella Karefa-Johnson who has since become the title’s global contributing fashion editor-at-large. Comparably, Annie Leibovitz has nine additional covers under her belt, five of which feature Black talent – despite ongoing criticisms of her inability to capture their beauty. At the time of publishing, Vogue has released four issues in 2023, none of which have covers photographed by a person of colour.

In addition to diversifying content, publications have doubled down on their coverage of racism – though it’s difficult to ignore the hypocrisy around the selectiveness of this. While Vogue is not alone, its response to Kanye West’s YZYS9 show best illustrates this.

Initially commissioning Raven Smith to (rightfully) call out the ‘White Lives Matter’ t-shirts, there were also rumours of a face-to-face interaction with West and Karefa-Johnson – following his tirade against the stylist on Instagram – filmed by Baz Luhrman. Later, Wintour and Vogue officially cut ties with him, following his anti-Semitic comments, though it remains to be seen if he will be given the same grace as John Galliano in years to come.

Meanwhile, Dolce & Gabbana continues to dodge cancel culture and is still reviewed each season and given prominent real estate space at the publication – its most recent cover in December 2021, worn by Sarah Jessica Parker. A friendly reminder that the brand’s racism isn’t just limited to a questionable campaign which led to the cancellation of its Shanghai show in 2018. There are also racist DMs, ‘Slave’ sandals (2016), posing with partygoers dressed as minstrels at a ‘Disco Africa’ party (2013), and a Spring/Summer 2013 collection filled with Mammy iconography and zero Black models (2012).

With publications and celebrities continuing to support the brand despite this, the consequences are twofold. For people of colour, it highlights that money will always speak louder than their condemnations. More worryingly, for those who should be fearful of the impact of being ‘cancelled’ – seemingly the only way to police these kinds of transgressions – they can simply avoid accountability by writing a cheque.

instagram

Now, three years on from 2020’s reckoning, there is an uncomfortable feeling among Black creatives working in fashion that after coming to a shuddering halt, the movement is now regressing – not that you’d be able to tell from your Instagram feed.

While there is little research specifically investigating this – though Quartz says it’s also regressing – scrolling back through various brands’ and publications’ feeds to find the aforementioned 2020 apologies, there appears to be a blanket of Black faces giving the impression of diversity. It’s a technique often implemented on the runway too. TheFashionSpot stopped publishing its seasonal report, but the Autumn/Winter 2022 shows revealed the smallest increase from the previous season since June 2020 – at only 0.6 per cent.

As diversity among models appears to regress, the work available for them becomes even more limited too. Levi’s was recently criticised for its use of AI models to create “a more personal and inclusive shopping experience” instead of simply hiring existing people of colour. Meanwhile, ‘digital supermodels’ like Shudu Gram – created by white photographer Cameron-James Wilson – are tapped for advertorials with brands including Ferragamo and Christian Louboutin.

There’s also something to be said about the way in which Blackness is represented in the imagery we consume. Now, fashion editorials that feature Black models have become homogenised, a combination of brightly coloured backdrops with the saturation dialled up to 100 to highlight their glossy complexion – seemingly taking cue from Rafael Pavarotti. Yet, when there are no discernible differences between images that we perceive as being associated with Black creatives and images that emulate the same aesthetic without including any, we must carefully scrutinise the blind spots that give a false sense of progress.

For Black people, this disparity becomes harder and harder to ignore post-2020. At the recent Autumn/Winter 2023 shows, Gucci’s interim collection was, for the most part, praised by my peers in attendance who lauded the Ford-Michele mash-up of covetable clothes. Admittedly, they were, but days later all I could think about is the fact that when the design team appeared to take their bow (11:38), everybody was white. In contrast, at Sunnei – presented on the same day, hours later – the collection was modelled by its own team, revealing (at least) 3 Black people working at the brand.

When I interviewed Serhat Işık and Benjamin A. Huseby about their Trussardi debut for AnOther, they told me that this lack of representation is sadly commonplace. “We had a visit to the headquarters to meet everyone who worked there,” Huseby recalled, “and we didn’t see a Brown person until the end of the day when the cleaners were coming into the building, which is very typical for a lot of fashion houses – especially in Europe.” Their short stint, reportedly because of budget constraints, is a blow both to POC designers hoping to make their mark at a fashion house – “Five years ago, we probably wouldn't have been appointed to this position,” Işık admitted – but also for any people of colour they opened the door for during their tenure.

instagram

The magnifying lens fashion found itself under in the midst of its reckoning gave me the rare opportunity to directly discuss the lack of diversity at the company I was working for at the time, as well as within the British Fashion Council – a timeline of the latter’s ‘achievements’ since can be viewed here. However, much like the efforts towards the inclusive future that we were promised at the time, the openness towards these conversations seems to have also regressed.

The discussions I had with other people of colour in the lead up to writing and publishing this essay made two things very clear. First, that very little, if anything, has been achieved in moving the dial forward. Perhaps more worryingly, is that people of colour are hesitant, if not afraid, of speaking up about the continuing impacts of systemic racism within fashion for fear of retribution. If you’re a writer, photographer, stylist, graphic designer, publicist, make-up artist, influencer – it doesn’t matter – the ramifications are as pervasive as ever.

Despite this, even now I don’t believe the responsibility of forging the path forward should be squarely on the shoulders of people of colour. If any progress is to be made, we need more white advocates who are willing to listen, support, and use their own voices to amplify this issue – especially when there aren’t any people of colour in the room.

Since 2020, I’ve been repeating the same phrase: ‘Everyone wants to change the world, instead of changing things in their own lane.’ To me this means a few things: What unconscious biases do I have that need investigating? How can I address diversity (or a lack thereof) in my workplace? How can I help amplify the concerns of people of colour? What power do I have to give people of colour (more) opportunities? What opportunities have been offered to me that can be passed on? It’s this line of thinking that has allowed me to investigate and work towards rectifying my own blind spots.

Throughout, I have specifically focused on the way in which Black people, and more widely people of colour, are impacted, but this could just as easily apply to other marginalised groups – people who are trans or gender non-conforming, working class, or disabled etc. Perhaps even more so, given that the absence of these identities within the industry is rarely highlighted in the same way.

Though my optimism in 2020 was sadly short-lived, the sooner we improve representation from the top-down, the sooner we can begin dismantling the systemic issues I’ve outlined, which in turn, will help from the bottom-up by removing obstacles that stop people of colour from pursuing careers in fashion in the first place – an issue I investigated for Dazed back in 2017.

Simply put, if the past three years have taught us anything, it’s that we don’t need more apologies or half-baked promises, we need action.

instagram

While there is still a long, long way to go, I want to end on a positive note, reflecting on the unique perspective that Black creatives can bring to fashion when they’re given both the means and opportunity to thrive.

At a time where we’re constantly bombarded with images, Imruh Asha – stylist and Dazed’s fashion director – manages to cut through the noise with work that is joyous, vibrant, and never fails to bring a smile to my face.

Elsewhere, Lindsay Peoples’ editorial direction for The Cut has transformed an astute platform into one that embodies everything I love about fashion – a balance of playful frivolity and intelligent scrutiny.

Finally, the lasting impact of Virgil Abloh is as pertinent as ever. Though I only had a single opportunity to interview him before his untimely passing, in the time since, I have come across more and more Black talents who have shared their stories of his kindness, compassion, and ardent support of them and others who look like them. While he is no longer here to guide us, his legacy remains, as well as his proposed roadmap to the diverse, inclusive future that we all deserve.

In his words: “I am so proud to have a platform that allows me to target, hire, and work with diverse teams of some of the most talented artists and thinkers to fuel every step of the creative process. We cannot reach an equitable future without first looking critically at how our own ecosystems help or hinder that growth.”

#diversity#inclusion#fashion#vogue#anna wintour#blacklivesmatter#black creatives#kanye west#gabriella karefa johnson#rafael pavarotti#imruh asha#virgil abloh#ib kamara#journalism#fashion journalism#fashion criticism#Instagram

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honey, We Shrunk the Interns.

Growing up, I never dreamed of pursuing a career in fashion. Right up until I left college in 2011, I was fixated on the idea of becoming a barrister. Although fashion was an avid interest of mine – one that I studied intensely, poring over my favourite magazines and keeping up with runway shows each season – it felt a million miles away from the reality of my quiet, suburban life. After all, it's not what you know, but who you know – fashion’s unofficial epitaph that is sadly still relevant over a decade later.

With no connections via relatives or family friends, I turned to Gaydar, determining that through the gay network I’d find an in. As luck would have it, I came across a young fashion photographer who put me in contact with his stylist flatmate to embark on my first internship.

I wasn’t paid a single penny, much to the dismay of my parents – who chose more reliable careers in building and finance – but my modest entry into the industry felt akin to the moon landing, at least to me anyway. I met models, hauled suitcases filled with returns on buses all over London, and peered inquisitively at the magic being made on set while steaming clothes in photo studios – marvelling at Prada samples that I recognised from the runway. I even met fashion royalty, in the form of Pam Hogg, who offered me a cup of tea when I turned up rain-soaked at her studio one sodden evening.

From there, an internship at GQ Style followed, the majority of which I spent sobbing in the bathroom thanks to the (nameless) editor at the time who often humiliated me with pointless menial tasks. In one instance, I was asked to hand deliver a single daffodil to Alasdair McLellan sans address, later loudly berated in the open plan office for the flower’s wilted demise by the time I was provided with the studio’s location.

My introduction to interning finished with a friendlier stint at Dazed – acquired via the gay network, once again – five years before I’d return in a full circle moment as a fashion editorial assistant.

Beyond the obvious hands-on experience my months of interning provided me, it quickly proved even more valuable than I realised. After initially being rejected by University of Arts London to study fashion journalism, a follow-up email clarifying the additional internships I’d undertaken quickly secured me an interview and later a prestigious place on the course.

Throughout my studies at university, we were encouraged to continue gaining industry experience, culminating in a term entirely dedicated to interning during my second year. Interviewing at Wonderland and 10 magazine, I chose the latter, and continued interning there throughout my final year – while simultaneously juggling my final major project, writing my dissertation, and a part-time job – until I ultimately became the publication’s fashion assistant upon graduation.

Over my career, I’ve had the privilege of working with hundreds of interns – the good, the bad, and the lazy – the brightest sparks among them going on to become my peers holding jobs at Clash, The Face, GQ, Wallpaper*, Matches, and British Vogue. As was my experience at 10, it was common for brilliant interns to find themselves earning entry-level full-time roles within Dazed and AnOther right up until the pandemic when the company’s internship programme was discontinued.

At the time, the Guardian reported that 61% of employers cancelled their placements due to the pandemic, with small and medium-sized businesses the most likely (49%) to do so. Yet, as we emerged from the two-year slump, internships were just as scarce, largely due to HMRC cracking down on unpaid internships – serving fashion publications (both the media and arts are serial offenders) with warnings of fines if they failed to pay interns the national minimum wage.

So, where does that leave today’s budding fashion journalists?

‘It is impossible, it literally feels like winning the lottery,” Moira Gonazález, an MA Fashion Communication student at Central Saint Martins tells me. ‘My plan was to join a team as an intern and work my way up, but it’s so difficult to start like that – maybe one person out of every 20 will reply and most of the time you don’t learn anything. I’ve ended up assisting so many stylists where I’ve just been in Ubers picking up stuff all around London. So many people still expect you to work full-time for free, which is crazy, but everybody’s willing to do it for fashion.’

Despite being required to complete 120 hours in the industry as part of her BA, Moira was the only person on her course who was successful in doing so. ‘The teachers said that if you worked on shoots for uni that it would count towards the hours, so there was no motivation to go out and get the experience,’ she says. ‘The process can also be so long, it took four months to get to the interview stage for an internship at Burberry. How can you survive living in London as a 20-year-old and pay rent if you have to wait for four months to get an answer? It’s impossible unless you’re privileged enough not to worry about money.’

To see for myself, I looked into fashion editorial internships in London to see what was currently available. Unsurprisingly, I failed to find a single placement to apply for and advice offered by the Business of Fashion overlooked the obvious, that no amount of experience or tenacity can help secure an internship if there aren’t any available to begin with. Reaching out to all the editors I knew, the results were marginally better with month-long placements available for university students only at 10 and the Evening Standard. The majority – including Elle, Wallpaper*, GQ, The Face, and Perfect – responded with a resounding no, with Vice allegedly going as far as implementing a company-wide ban on all internships.

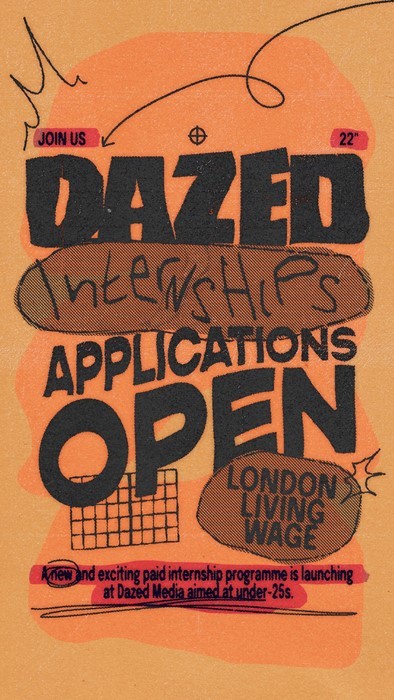

Of the paid internships the government were hoping would become available, only Dazed and British Vogue currently offer them – both six months, full-time, and paid the London Living Wage – though at the time, the vacancies were filled. ‘I remember when British Vogue posted the internship on LinkedIn and after two days they already had 500 applicants,’ Moira says. ‘When I later saw who got the internship, she had worked at two banks previously, studied politics, and was 25 or 26 so had a much bigger CV. How can I even compete?’

‘For me, I’ve always found that there was never a clear route into the industry, I didn’t have a degree and my parents aren’t creative – there’s nobody in the creative industry in my immediate family. I wasn’t getting anywhere and couldn’t get my foot in the door,’ says Louis Merrion, Dazed Digital’s inaugural paid editorial intern. ‘I had come to a point where I was looking at unpaid internships, but I’d have to work weekends to be able to afford to commute from Southend. All of sudden you’re working seven days a week and you could come out of the end of it without having gained any experience. It’s easy to see why people get so disillusioned with the system.’

Three months into his tenure at Dazed, Louis’ day-to-day involves tasks that you'd expect for aspiring writers: shadowing working journalists, transcribing, researching, pitching and writing their own stories. ‘It feels more like an apprenticeship than an internship because of the learning aspect of it, you’re not expected to come in and know how the industry works straight away,’ he adds.

With several bylines now under his belt, Louis is already using the opportunity to gain additional experience working alongside Dazed’s social and Studio teams, which he hopes will set him in good stead once his internship ends. ‘I couldn’t ask for a better first creative job and the experience I’ve gained is invaluable,’ he says. ‘I now feel like somebody who is actually involved in the creative industry as opposed to being a part-timer; I have the belief that I could have a career in it. It’s not as far-reaching as it seemed six months ago.’

It sounds too good to be true and for most it will be – the cost of paying the LLW means that spaces on such internships are currently limited to two golden tickets per year. What do you do if you're not so lucky?

instagram

An alternative path into the industry – thanks, in part, to the diversity reckoning fashion faced in 2020 – are mentorships that pair beginners with working creatives for 1-2-1 support over a six-month period.

Mentoring Matters (founded by Laura Edwards, a design director who has worked with Christopher Kane and Alexander McQueen), Room Mentoring (founded by Elle's editor-in-chief Kenya Hunt), RAISEfashion, and The Junior Network are a handful of these schemes born during the pandemic – generally aimed at aiding Black and brown creatives and those from working-class backgrounds.

In 2021 through Mentoring Matters, Aswan Magumbe, a BA Fashion Communication student at Central Saint Martins was paired with i-D’s global editorial director Olivia Singer. ‘Mentoring was more personal, so Olivia helped me pinpoint specific things I needed help with like pitching and how to approach PRs. I also got a lot more in-depth feedback about my writing,’ she shares. Yet, even with this, Aswan admits, ‘I’m still very stuck. Mentoring is good because you have somebody to turn to, but I still don’t know how to navigate internships. I really don’t know the route to take.’

As a working journalist, I’d be hesitant to take on a role as a mentor for this very reason. While I could impart practical wisdom on how to be a writer, I have no means of offering advice on where to practise those skills. While well-intentioned, these mentorship schemes are guiding marginalised voices into an industry that has been reluctant to give them a seat at the table to begin with. How responsible this is without fully understanding or doing more to remove the roadblocks that sadly still exist remains to be seen.

It’s a complex issue, yet to be properly acknowledged – the disheartening reality is that many editors I spoke to weren’t aware that their publications no longer offered internship opportunities. I urge them to similarly reflect on their own arduous journeys – regardless of whether they grafted as an intern or not – and question leadership on why they aren't putting more time and resources towards supporting the talents of tomorrow. Take a chance on a new writer with no bylines, become an unofficial mentor, answer that email asking for advice – do more!

We’ve talked enough about making opportunities more readily available for those who want to pursue a career in fashion – it’s time to finally do something about it.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashion In Flux.

As 2022 drew to a close, the tectonics slowly began shifting; now, as we embark into 2023, fashion is finally facing a major vibe shift.

While the past seven years have been peppered with rising talents and breakout stars, following the last seismic shift, it has undeniably been a two-man race between Gucci’s Alessandro Michele and Balenciaga’s Demna.

Until it wasn’t.

Following Michele’s recent announcement that he’d be parting ways with the Italian house, occurring almost simultaneously with Balenciaga-gate, fashion finds itself in a state of flux.

Michele’s appointment as creative director back in 2015 came as something of a surprise – triumphant over more recognisable names including Riccardo Tisci, Christopher Kane, Joseph Altuzarra, and Tom Ford, again – with Kering’s chief François-Henri Pinault tasking the designer with taking the house in a ‘daring direction’ following predecessor Frida Giannini’s early exit.

It’s a formula we’ve similarly seen strike gold in the years since with Daniel Lee at Bottega Veneta and Daniel Roseberry at Schiaparelli, but it has also been catastrophic, in the case of Justin O’Shea’s breakneck seven-month tenure at Brioni and Lanvin’s seemingly revolving front door.

Revisiting his Autumn/Winter 2015 debut (the unofficial one), Michele’s maximalist magpie tendencies weren’t as grandiose as we’ve come to expect, but his willowy boys with their luscious locks, pussybow blouses, fur-lined slippers, and nerdy, oversized reading glasses were a world away from the stark streetwear we were seeing in menswear at the time. Similarly, his womenswear debut was an entirely different offering to Miuccia Prada’s smart and subversive Prada, Hedi Slimane’s svelte and skanky Saint Laurent, Nicolas Ghesquière’s sleek and chic Louis Vuitton, or Phoebe Philo’s salve for all wounds, Céline – before Slimane later axed the é.

After presenting four collections – his AW15 menswear and womenswear debuts (presented separately, before the brand went co-ed in 2017) a Resort 2016 show in New York, and a stepped-up sophomore menswear outing – Michele was awarded International Designer of the Year at the 2015 British Fashion Awards for having ‘set the fashion agenda’ and ‘confirming Gucci’s position as a truly directional fashion house.’

Meanwhile, Demna, who we now know as the mononymous creative director at Balenciaga, was still somewhat unknown, just beginning to step into the limelight as design lead at Vetements, presenting his sophomore collection during the same season. He would be named as Alexander Wang’s successor seven months later in October 2015.

In the years that followed, both designers began laying the foundations to create the behemoth brands today, albeit at opposite ends of the spectrum – Balenciaga the dark and dirty counterpart to the romance and nostalgia of Gucci.

There’s the inescapable assault from both brands as the go-to for your celebrity faves: from Balenciaga’s Kim Kardashian, Kanye West, Dua Lipa, Elliot Page, Justin Bieber, Isabelle Huppert, Michaela Coel, Nicole Kidman, and Kylie Jenner to Gucci’s Harry Styles, Jared Leto, Lana Del Rey, Florence Welch, Måneskin, Miley Cyrus, Phoebe Bridgers, Billie Eilish, Dev Hynes, Idris Elba, Janelle Monáe, Julia Garner, Andrew Garfield, Jodie Smith, Jack Grealish – you get it.

Yet amid standout shows (Autumn/Winter 2018, Spring/Summer 2019, Resort 2020, and Autumn/Winter 2022) meme-orable moments (from severed heads to platform Crocs) and cohort of collaborations (adidas times two, Palace, The Simpsons, Disney, and even each other in fashion’s first multiverse moment) their commonality stretched beyond the creative into their forward-thinking business mindset. Whether partnering with the World Food Programme, aiding employees to find safe abortions, ditching fur, platforming upcoming design talents, hiring diehard stans, or branching into beauty, Demna and Alessandro represented a ‘new’ kind of creative director – simultaneously scrutinising the finer details while taking scope of the bigger picture.

Yet it’s this painstaking attention to detail that makes Balenciaga’s recent ad scandal even more perplexing. Despite the brand initially blaming production company North Six – with a $25m lawsuit that was swiftly dropped – insiders question, rightfully so, how such images could see the light of day with so many stakeholders involved.

Regardless of which side of the scandal you find yourself on, it’s impossible to ignore the endurance of this particular controversy. Thanks to the Right’s rebirth of ‘Satanic Panic’, luxury brands are forced to walk an ever-shrinking tightrope to do the ‘right’ thing, not because they want to, but because they have to in order to protect their bottom line. Remember when controversial ads were en vogue?

Since Balenciaga-gate, Gucci found itself under similar criticism following the release of its ‘HA HA HA’ campaign – featuring Harry Styles wearing a teddy bear t-shirt toting a mattress that denigrators said belonged to a ‘toddler’. In a now deleted TikTok video, Coach was decried for Disney-themed teddy bears in its Sydney store that were described as ‘satanic’ and ‘evil’.

For Balenciaga, the fallout (still falling) from its Chernobyl has seen Kim Kardashian, the poster child for Demna’s Balenciaga, noticeably out of the brand claiming to be ‘shaken by the disturbing images’ and ‘re-evaluating her relationship with the brand’. After appearing in the brand’s AW22 campaign, Euphoria’s Alexa Demie deleted all Balenciaga images from her Instagram feed and promptly unfollowed for good measure. Then the Business of Fashion rescinded its ‘highest honour’, the Global VOICES award and instead asked the brand representatives to attend to explain the saga – they declined.

As the brand’s first show post-Balenci-gate approaches, the mind intrigues whether deep-thinking Demna will address the controversy. Amid the storm that has permanently taken root above Balenciaga HQ, the designer and CEO Cédric Charbit seem to be on borrowed time.

So, who does that leave in line to succeed fashion’s Iron Throne? At the end of 2022, Miu Miu took home Lyst’s title of hottest brand of the year for the first time – beating away heavyweights Balenciaga (who has topped the chart six times) and Gucci (topping 10 times and never placing lower than 4th).

Thanks to its viral micro skirt set – which solidified its status on countless covers and via Shein knock-offs and homemade Halloween costumes – Miuccia trebled down from Spring/Summer 2022 through to Spring/Summer 2023, turning Moo Moo into a cash cow with churning out micro bras and adorable accessories.

There’s also the new guard of next gen designers invited to make their mark at hallowed houses: Ludovic de Saint Sernin and Harris Reed will shortly present their debuts for Ann Demeulemeester and Nina Ricci respectively, while Maximilian Davis will reveal his sophomore runway collection for Ferragamo. With luck, an exciting opportunity to see what they’ve got, and not another revolving door. Bianca Saunders and Priya Ahluwalia next please!

Will Matthieu Blazy achieve a hattrick at Bottega Veneta? What has Raf Simons got up his sleeve? What Ever Happened To Phoebe Philo? With heavyweights in limbo – Alessandro Michele, Riccardo Tisci – a hotly anticipated debut from Daniel Lee at Burberry, and open spots at Louis Vuitton menswear and Gucci, the guillotine looks like it’s readying for more chops with LVMH’s recent CEO moves.

Time to place your bets.

#fashion#balenciaga#gucci#demna#demnagram#alessandro michele#miu miu#miuccia prada#matthieu blazy#daniel lee#phoebe philo#raf simons#bottega veneta#burberry#louis vuitton#prada#lvmh#kering

6 notes

·

View notes