Text

Works Cited

Baldwin, James. The Fire next Time. Michael Joseph, 1963.

BULOSAN, CARLOS. America Is in the Heart. PENGUIN BOOKS, 2022.

Deloria, Vine. We Talk, You Listen. MacMillan, 1970.

James Baldwin - Pin Drop Speech - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NUBh9GqFU3A.

Taylor, Susie King. Reminiscences of My Life in Camp: An African American Woman's Civil War Memoir. University of Georgia Press, 2006.

Vine Deloria Jr. on Technology’s Toll - Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-XGnk4VbeA.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Democracy and Civic Engagement (In three parts)

Arguably more than any other time in American history the juncture after the civil war was a period of formation. Many Americans had only just begun to reap the benefits of freedom following the emancipation proclamation. With this formation came debate on what the best steps forward were, and one of the loudest voices in that debate was Josiah Strong. While being obscure by today's standards, Josiah Strong’s rhetoric has lived a thousand lives. Strong’s work Our Country became the roots of the sapling that bloomed into modern academic ethnocentric thought in the US. Trampolining off of westward expansion and pseudo-scientific notions of racial hierarchy Strong’s work describes the United States as being an Anglo nation facing, “the most remarkable migration of which we have any record” (Strong 80). In an attempt to remedy future conflict Strong encourages the people of the United States to inscribe positive values onto incoming immigrants. Distinguishing itself from its scion’s the work doesn’t promote isolationism, rather it encourages the people to imbue Anglo Saxon values onto newcomers as to reduce discrepancy as much as possible. As well-meaning as strong may have been, his work was inevitably co-opted by racial purists who took the idea of Anglo-Saxon superiority and ingrained it into American society. Instead of making America into a “Land of promise”(Strong 80), they instead opted to turn it into a land of exclusion.

While Strong put the mindset to paper and no doubt inspired many Anglo men to adopt the same mindset, the caste system of the United States had been in place for decades. One example of this caste system being written into law came with the Indian appropriations act of 1871. Written into a routine allocations bill, the act established that the united states could no longer make treaties with Indigenous people, fully colonizing what was left of the American tribes with the signing of a pen, “hereafter, no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be recognized as an independent nation…”(Congress 566). With time the written bias became obvious with the statement that was the Chinese exclusion act of 1882. Standing as the first and thankfully only law to ever prevent specific nationalities from immigrating to the US, the act banned all Chinese laborers for a period of ten years,

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That from and after the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act, and until the expiration of ten years next after the passage of this act, the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States be, and the same is hereby, suspended”(Congress 2)

These were followed still by Plessy vs Ferguson in 1896 and Ozawa vs United States in 1922. Plessy vs. Ferguson established the “equal, but separate”(Louisiana 1) standard of segregation and Ozawa vs United states which denied naturalization to non-Anglo races, “The provisions of this Title shall apply to aliens, being free white persons”(US 1). While these legislations may seem like a faded memory to most, they were a real and tangible barrier for many US citizens' entire lives. It is only through an analysis of these people’s work that we can gain something of an understanding of their situation and provide a complete survey of these moments in American history.

Works:

Despite being one of the more contemporary works we’ve covered, I feel like Vine Deloria’s We Talk You Listen is one of the more profound works we covered in the catalog. This sentiment comes from the book's vision of the future and its unfortunate prostignations. Being raised in the early 20th century on a South Dakota reservation, Vine witnessed firsthand the effects of the trampled treaties that had reduced the once thriving native population. This legal and societal disposition that his people had been left in went on to largely define his life’s work. Writing about the natives of the United States Deloria became an author of esteem; however, in my mind his most significant work is We talk you listen as it effectively predicted many of the problems our society faces in the modern day.

“It is not even as simple as that. Symbolism has taken a turn toward the unde.6.nable, because the language structure, insofar as it communicates meanings, has collapsed as the old environment has been reprocessed. If the medium is the message then there really is no symbolism. External definition of image and symbol as objects of knowledge is no longer possible. Internal and external are now one.”

Through the work Deloria covers the effects of industrialized living on the human spirit, showing how it kills the spirit and destroys meaning; however, his goal goes much further beyond simple reprimands. Deloria proposes that the only way to help the United states is to turn to a more traditional and Native way of life. Through group identity and a more tangible effort to develop communities Deloria believed that America would prosper. Looking past the shining lights and avarice that ensnared the American people Deloria’s idea of Neo-Tribalism stands in my mind as a prophetic look at the society of the time. Considering that half a century later the problems outlined in his work have only gotten worse, it makes one curious as to if an ideology like Deloria’s could have changed the outcome of things.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-XGnk4VbeA

“God Gave us the rainbow sign, no more water, the fire next time!” the thundering words open American Author James Baldwin’s masterwork The Fire Next time. Born in Harlem in 1924, Baldwin was baptized and formed by the hatred that surrounded his community, enduring and rising above what would have broken most. Instead of succumbing to the overwhelming mass of bigotry that surrounded him Baldwin took all of his rage and turned it into prose, describing the situation in a letter to his nephew,

“This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. Let me spell out precisely what I mean by that, for the heart of the matter is here, and the root of my dispute with my country. You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were 18 black and /or no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever.”(Baldwin 19)

Baldwin saw through the veneer of superiority that the Anglos of the United States had and saw his situation for what it was: an unnecessary show of insecurity. For some preternatural reason the Anglo population of the United states needed an “other”, someone to cast out and climb on top of. Baldwin described such a thing as essential to their psyche’s,

“ Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame. You would be frightened because it is out of the order of nature. Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one's sense of one's own reality. Well, the black man has functioned in the white man's world as a fixed star, as an im'.movable pillar,: and as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.”(Baldwin 20)

In the face of this lived experience full of hatred and uncertainty Baldwin responded with an ultimatum of eventuality. In Baldwin’s mind, if the Anglo people of the United States were unable to come to terms with the reality of equality, there would be an inevitable equal and opposite reaction to all the pain that had been inflicted. Baldwin’s proposition for a better world was one of equality, while we may be living in the closest approximation of that ideal ever achieved in the modern day, to someone like Baldwin that ideal was about as attainable as living on mars. I only hope that we’ve achieved enough in the years since to avoid the inevitable collapse, reversing the entropy of the natural path of the projectile towards the end,

“I could also see that the intransigence and ignorance of the white world might make that vengeance inevitable-a vengeance that does not really depend on, and cannot really be executed by, any person or organization, and that cannot be prevented by any police force or army : historical vengeance, a cosmic vengeance, based on the law that we recognize when we say, "Whatever goes up must come down."(Baldwin 112)

Perhaps the most tragic figure in this curriculum, there was no certainty for Carlos Bulosan. Born in 1911 in the Philippines, Bulosan was forced to abandon his home at 17 years old due to the economic devastation that had ravaged his life. Upon moving to the United states with the hope of finding prosperity or the American dream, he was met with violence: both physical and verbal, witnessing a cop murder a young kid almost immediately after his arrival, “The boy fell on his knees, face up, and expired. The players stopped for a moment, agitated, then resumed playing, their faces coloring with fear and revolt. The detectives called an ambulance, dumped the dead Filipino into the street and left when an intern and his assistant arrived. They left hurriedly, untouched by their act, as though killing were a part of their days work."(Bulosan 129). In spite of this Bulosan never stopped hoping and striving for the America he was promised. Joining and being outed from unions and traveling the country Bulosan spends the entire text fighting for what he was promised: a society of reasonable conditions for people of all backgrounds. In effect the future that Bulosan hoped for as a surveyor was what America was promised to be on paper,

“It is but fair to say that America is not a land of one race or one class of men. We are all Americans that have toiled and suffered and known oppression and defeat, from the first Indian that offered peace in Manhattan to the last Filipino pea pickers. America is not bound by geographical latitudes. America is not merely a land or an institution. America is in the hearts of men that died for freedom; it is also in the eyes of men that are building a new world. America is a prophecy of a new society of men: of a system that knows no sorrow or strife or suffering. America is a warning to those who would try to falsify the ideals of freemen.”(Bulosan 189)

Tragically, America remained elusive to Bulosan, working backbreaking labor his entire life until his death in 1956 at 42 years old. While Bulosan may have never seen the America he dreamed of, I like to believe that we’re working towards it every day.

Susie Baker King Taylor very well could have ended up lost to the history books. Written only decades after the bloodiest conflict in United States history, Reminiscences of Life in Camp tells the story of a wartime hero. Surviving as the only African American woman’s memoir of the time period, Taylor documents her time in the civil war with brutal specificity. Being born in the south her life was largely affected by the bigotry of those around her, being extremely limited in educational materials. In spite of this her learning aptitude was off the charts, even being told by a teacher at eleven years old that she needed to seek other outlets for information as Taylor had exhausted their educational ability. In spite of the bigotry she faced, or maybe because of it she took to the union forces as a nurse during the civil war. In a display of saintlike selflessness she worked for over four years as a combat nurse without receiving a dollar of payment,

I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services. I gave my services willingly for four years and three months without receiving a dollar. I was glad, however, to be allowed to go with the regiment, to care for the sick and the afflicted comrades”(Taylor 20).

It is only through the final section of the book that we get a glimpse into her personal thoughts and feelings on race in America. Taking an extremely moderate position, Taylor believed that over time the barriers between the races would break down and they would receive the true equality they had fought for during the civil war. More than most in history, Susie Baker King Taylor fought for the world she believed in.

Epilogue

It is hard to say definitively what Susie Baker King Taylor would think of the modern world. With years of fighting and dying for the most basic of courtesies behind her, the modern world would appear as a utopia. Legal equality for all Americans is most likely beyond anything Taylor could have imagined possible in her time, a, “Land of promise, there to thrive and be forever free from persecution” (Taylor 75). Gravity’s rainbow was extended, our natural arc continues, and the fire has yet to exact its vengeance, one can only hope that in all the confusion we never lose sight of what was sacrificed and where we need to go.

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Text

On studies of American Literature (in two parts)

America isn’t perfect. Like every country America has a history of miscalculations and harm, some of which continue to do harm to this day. One of the most prevalent injustices perpetrated by America as an institution is the underrepresentation of certain ethnic and social groups in the field of academia. For a majority of American history many brilliant authors and artists went almost completely overlooked in favor of those of higher “Caste”, as such when learning about our history it is essential to learn about it from all Americans. Such was the same thought process as author and educator Michael Hames-Garcia when he wrote the essay Which America is ours. Within the essay Garcia describes the civic duty of the culture critic, stating that for one to truly gain any sort of insight into American history, one must view texts beyond simple aesthetic muses and view them in the political context of the United states at the time. Garcia believes that by evaluating this work politically the student is able to challenge their beliefs and engage in a meaningful cultural debate with the text, “What I am really interested in, however, is not just context but debate—not debate for its own sake, but with the understanding that different positions can and must be evaluated for what they can tell us about what is "American," what is "literary," and what is “right”.”(Garcia 34); however, such a statement brings up an important question: that being the exact meaning of context in this, well context.

For an answer to that question we turn to Professor of English Joel Pfister's work The critical work and critical pleasure of American literature. Within this introduction Pfister outlines what are essentially guidelines to reading a text academically. You may be asking what the difference would be between a casual reading and an academic reading, and the answer is methodology. What Pfister is asking you to do when you read a text academically is to effectively take a kaleidoscopic view of the text. For example let's take a look at the poem The second Coming by William Butler Yeats.

Reading: https://youtu.be/QI40j17EFbI

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

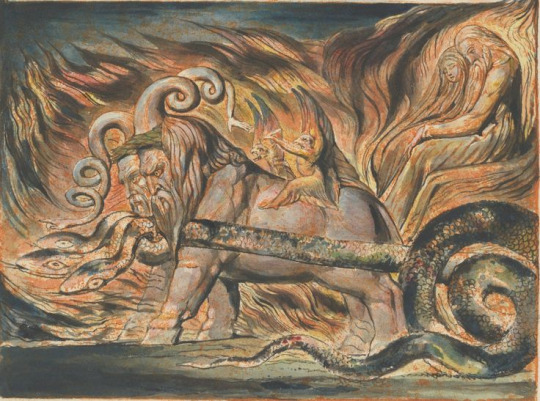

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

If one were to read this poem in a nonacademic sense some obvious themes arise. There's an overarching sense of doom and confusion compounded by biblical references; however, when looking at the poem through an academic view a much truer meaning reveals itself. Surveying the text in depth reveals that Yates isn’t expressing a personal tragedy, but is simply crying out for the future of humanity following one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history, World War one. More than an expression of angst the poem almost reads like a tragic prelude for the eventual second world conflict. Such context highlights the importance of being what Pfister called a surveyor of American customs; ergo, it is with the methods outlined above that I went about critiquing and dissecting the works in this course.

1 note

·

View note