Photo

Chicago--Devon--once painted his face and mimed a routine to some song I should have known, in chapel, long arms swinging wide to the piped-in music.

Mr. Teal, not a student like these others, has walked me through any question that touches a federal program; he helped write half the guidance, when he worked at the Department, you see.

Sha’Amion worked with me in the Registrar’s office and wants to run a funeral home. I don’t know what that says about me.

Juanita is staying on to work with us in our fin aid department. When she was in high school she and her friends put together an informal group to help folks get launched into college. No pay, no framework, no grown-ups to help. Just an understanding of a need, and each other.

Graduation Day.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Starting three years ago I have spent a part of a morning in the first week of March walking east on Main Street in Dallas, retracing the route that a lynch mob of well-dressed Dallasites took over a hundred years ago. The terror lynching of Allen Brooks—its elisions, its souvenirs, its irreducible quantum of anguish—is a key to the neuralgic mythmaking and self-justifications that this city calls History. Unmarked, it casts no shadow; a nail’s head driven flat, an invisible medallion in the earth. A pattern of blows fixes it to the ground, the traces of hammer strikes like fingerprints in steel.

But there are other patterns.

I did not walk the route this year. This year in the first week of March, a couple nights ago, I did scramble a few blocks from our place over to Deep Ellum to meet our college president and a smattering of staff, all gathered to celebrate the Top 20, the students with the highest GPA’s from the fall.

We took up the room, crammed alongside each other in a long mish-mash of tables pushed together in a crowded restaurant, some students talking and laughing, others shy or a little out of place, some done up and others rolling right up to the edge of the dress code. Accents: Haiti, northern Mexico, northern Mexico once removed, Southeast Oak Cliff, Boston. All over. A student, an unassuming kid—no. He’s a man, of course. But it’s hard for me to see the youth in those eyes and not think of them as kids. Anyway, he used to work in my office and he’s at the foot of the table, hair firmly slicked back, bright bands of color on his polo shirt contrasting with the blue green of his forearm tattoo in the warm, low light. We roast each other and joke, learn names—a woman in her fifties finishing her religious studies degree; the young man in head to toe black, insisting he didn’t know his grades were good until he got the email inviting him to dinner; what seems to me to be a nascent couple smiling at the corner of the table, trying out a new way of being around each other.

I gulp black coffee while they stuff themselves with terrific pizza and the night winds down. I leave with the last of them, counting heads reflexively, unnecessarily, knowing everyone is grown; I wheel around toward the alley where I’ve parked and walk east down Commerce, parallel to Main. I move now and think my way through this old neighborhood. I consider the strata and the names, the figures—Central Track, Deep Ellum; Blind Lemon Jefferson. I consider the way they’re sandblasting the Knights of Pythias Building, stacking twenty stories of luxury apartments next to the first building by a Black architect in the city; a little jewel in a setting of multi-use development, floating on a sea of capital. I consider the bricks and iron of the old warehouses, machinists, butcher supply stores; what was all these and more once wound around the K&T rail in a glittering string of juke joints and brothels and streetcars and good houses stretching from here to where the CityPlace tower now stands stabbing streaks of unblinking LED lights into the sky across from the Freedman’s Cemetery and what once was State-Thomas, and now, like here became studios, then bars, and now restaurants with valets.

The people who laid these bricks and cut railroad ties for miles north, south, in a tangle around the center of the city? They built the wealth into the land as surely as time pressed the blood of dinosaurs into oil but this city never let them share in its riches, still won’t; its instinct for sharing as dry as the Trinity in July. But those hands looked just like these hands I’ve been drinking coffee next to and those hands built this school too and when I walk I think of them. All these streets are their birthright, this city is. But it does not belong to them.

Or let me say this way: it does not belong to them. Yet.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forty Years Forward

One morning this week I waited in the library for one woman to meet another. One had traveled a long way, the other had not. A husband, a sister, waited too with the one who had traveled--a woman with a cosmopolitan voice, clear, patient.

There is a little happy commotion when her old friend makes it. They stand and talk, after they embrace, next to a dress she or the other had danced in. Maybe both, in the company they had started together: part of a display telling a history of this, the Black Dance Theater. Their Black Dance Theater. Yellowed clippings in a book and a case with playbills and photographs, brightly colored costumes, glistening faces in performance.

The old friend had stayed behind in this city to build the theater they started together and they have seen each other not infrequently but still they are glad, hugging one another. Both know our librarian, who seems to know everyone.

The dress is orange and blue underneath a sheath of white cotton.

“You know the company started here?” the librarian mentions to me, while they are murmuring by the display case, a photographer clicking away, a theater staffer streaming things on facebook.

“On the campus?” I say, surprised.

Yes, and in a building since razed to the ground (green grass there now: a question mark, a possibility; a great emerald arm reaching to the next thing) on the south part of the grounds. They started dancing, and kept on, building around both of their arms and waists and chins held at precise angles. So many stories I have yet to learn.

They held themselves, together. Forty years gone by.

--

Getting in the car this morning with S. I notice I have left a rake out by the porch this past week, exposed to the sun and, for the past day or so, the rain. It has gone from tan to grey; washed out. Around it a bush, which I think may privet, is unruly. Bright green weeds mix in with the purple diamond leaves of oxalas and the the freckled orange petals of transplanted day lily from L.’s sister’s yard. Though I don’t work as hard as I should to support it, in contrast to the faded wood of the tool the crepe myrtle is brown-green; shoots pushing out all around, waxy leaves and pink flowers around the four or five crooked stalks of trunk, heedless. It has endured the same week of punishing sun and sudden rain as the neglected tool. Though both are themselves independent of me, the contrast is sharp, given that --

the tree remains flowering

holds its color

is alive

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Stripping of the Altars

The kids should rename those schools something boisterous or interesting or weird, and Black artists should get to treat the empty spaces where the monuments were like a blank canvas for generations to come, taking turns, narrating the absence, correcting the decades of violent misremembrance. Radiant glass columns or great piles of broken chains or a mirror three stories high or fountains on top of fountains for a river of tears that little kids can play in, or an African drum so large and loud we can feel it in our feet when struck--anything.

These reconsecrations -- demolition, renaming, making anew -- are the concrete ways of converting, together, away from a lie.

Let me be clear.

As soon as he came near the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, Moses’ anger burned hot, and he threw the tablets from his hands and broke them at the foot of the mountain. He took the calf that they had made, burned it with fire, ground it to powder, scattered it on the water, and made the Israelites drink it.

Exodus 32: 19-20

There are the soles of feet turned up in that photo--the red circles at the heel and toes of the man sliding down off the trunk. Diagonal from his folded body are two socked feet exactly vertical, in line with the legs; black pants obscured from the knees up by the crowd into which that body is crashing head-first. Someone’s foot up is smack against the bumper of a pickup in the bottom right of the frame. Another man’s body is in full view, suspended a foot above the car, his head at a sickening angle, legs askew. There is dust and there are shoes in the road. The brake signals are dark.

What do you see?

“We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence. On many sides. On Many sides.”

Many sides.

No accidents there; no words fell to the ground. A distinct vision of the world is operating there.

But there are other visions.

The day after the 2016 presidential election we held a town hall at the College to work through its consequences with our students. I have mentioned this before on here, I think. We have DACA students and we are an HBCU and the news was relevant to every one of them, their families, their cities. Of course being nineteen means half the time you think you are invincible no matter what. But one woman fainted. Anyway, one of our former trustees got up and said that this school made it through Reconstruction, that it made through the Civil Rights Movement, and that we would make it through this. It was an assurance, but it was not meant to put anyone at ease.

In 1916 ten thousand people burned Jesse Washington to death just across the Brazos from the College’s campus, when it was still in Waco. They convicted the editor of the College’s paper of libel for saying that George Fryer killed his wife, and not Washington, the Black man they had accused. They sold Washington’s fingers for souvenirs.

Moses said to Aaron, ‘What did this people do to you that you have brought so great a sin upon them?’ And Aaron said, ‘Do not let the anger of my lord burn hot; you know the people, that they are bent on evil. They said to me, “Make us gods, who shall go before us; as for this Moses, the man who brought us up out of the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him.” So I said to them, “Whoever has gold, take it off ”; so they gave it to me, and I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf!’

Exodus 32: 21-24

One of my friends was speaking at a rally last week, urging Dallas to take down its Confederate statues, to change the names on the roads and schools named after Klansmen. A little group was gathered to oppose the not-overwhelming crowd arguing for removal. My friend is an A.M.E. preacher. He talked about Mother Emmanuel and begged the City to move first before some tragedy engulfs us. The counter-protesters screamed their defenses of Robert E. Lee while he spoke; screamed defenses of their own families; interrupted him. He gave back their words, asked them to explain themselves, to imagine the fate of his family if Lee had accomplished his purposes. When our local glossy magazine wrote it up, they explained that the Confederate engaged while the Black preacher ignored interlocutors.

How to explain this?

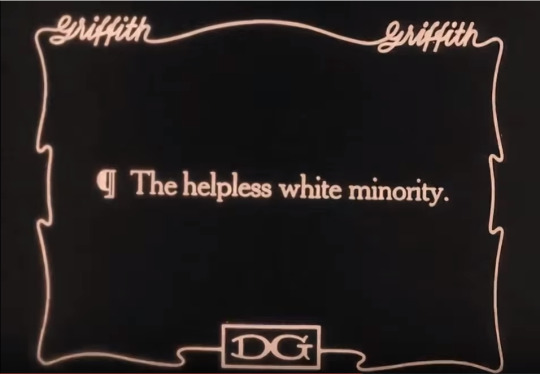

All the principle Black people in the Birth of a Nation are played by white actors in blackface. Imaginary Black people, imaginary history. Amy Louise Wood has argued that the boundaries between the spectacle of Griffith’s epic and the spectacle of terror lynchings are porous; borrowing from each other and confirming a vernacular of controlled mayhem, all doing what always has been done at the spectacle of the altar: making a cosmos out of the brute world, making a place for you in it, if you will submit.

The false memory encoded by these statues and inscriptions on our streets and schools partakes of the same nature as the film because it tells the same story as the film: happy slaves, outside agitators, genteel planters, brave Confederate soldiers braver on return, lascivious Black rule, exploitative carpetbaggers. By the end of the film North and South are allied in rejecting Black misrule. All avoidable, if we simply could solve our problems without recourse to war. If we could have been more unified and understanding. These are the elements of the Lost Cause that cohered to underwrite Jim Crow then and de facto apartheids now--to excuse it, to rationalize, to culturally approve it; to baptize it. This vision of the world is in competition with another one; of them, one allows you to see Robert E. Lee without seeing Allen Brooks, and that makes it a falsehood.

In its erasures of Black slaves, Black soldiers, and Black freedom, the shrines offer us a profane transubstantiation: the sublimation of racial terror into white victimhood. This inverted eucharist was the precise method used to engineer white social cohesion in the aftermath of civil conflict, as David Blight and others have argued, and as Josh Marshall so compactly noted this week.

Thus, all around the pedestal of these statues swirl the ghosts of history’s most successful campaign of racial terror, memorialized almost nowhere, re-encoded every time a Black girl is presumed to be much older, every time a Black man’s lack of deference is taken as a threat. The line from Robert E. Lee’s nobility to Tamir Rice’s lack of innocence is a straight one. It is a straight line.

The statues lie. The lie absolves, the lie makes natural; the lie gives you an alibi. It is as important forensically as grace, collectively speaking, and is in that sense the lie is a faith. And Birth of a Nation is a symbol of this faith, a creedal statement; its statues are shrines and reliquaries; its schools incantations.

Every statue and school that bears the name of a Confederate hero or a Klansman is a local instantiation of the inverted miracle that white violence has called into the world: cut a man and blame him for spilling blood on your carpet. Fire into a crowd and count the chaos as evidence that your strong hand is needed. Aaron, shrugging idiotically, claiming the calf sprang fully formed from the fire; as if natural, or a sacrament; as if the false god is not of his own making. To blame the people against whom whiteness commits violence for the existence of violence: this is the special blasphemy of our country’s besetting ideology.

So when Pilate saw that he could do nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took some water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.’

Matthew 27:24

As an undergraduate I learned about the letter of Gregory to Abbot Mellitus in 601 CE, passing instructions on to Augustine for the Christianization of England. Bede, the historian, tells us that no longer were they to crush or destroy pagan shrines, but they were to reconsecrate them. How big of an impact this really had is up for debate, but we do have Bath to show for it, and megaliths in churchyards; probably the Easter Bunny.

Either grind it to dust or give it a new name. That is what you do to the world that came before, if you are converted, if you come to see the cosmos as ordered differently.

I do not know just what to do next with the symbols of the confederacy; to erase them or to reconsecrate the spaces somehow, tangling up their destruction in the enactment of a new method of remembering and forgetting. Maybe it is not for me to know, but just to mourn, to add my voice to the mourning of this horror that points to the horror in our whole landscape. To think that our collective interventions on the landscape are neutral--any of them--that we can evade responsibility for what buildings we tear down or build or the lynchings we have not bothered to mark is to make Pilate’s mistake, which is to presume we can wash our hands of the cruelty that is present to us. It does not matter how hard you scrub. You are born to this stain. So it is to us to at least to make space for something new to grow. Kids, artists. I trust them with the reconsecration.

From a certain vantage point in lots of places where I grew up in Georgia you could see Stone Mountain in the distance, orienting you. We went to the laser show, the fireworks in the summer, lighting up the general’s faces while Elvis Presley sang the Medley. But I know what those generals mean and what that mountain was for, and we would lose nothing by wiping the statues off the face of that monolith. You can bring the whole thing down, turn it into a pit. I don’t know what comes next, but for now we can narrate the absence, bake the gravel into cakes. Nothing about Robert E. Lee’s full humanity keeps us from grinding Stone Mountain to grey sand and scattering it in our water, that we might repent in dust and ashes. I could still find my way home. We could.

#TakeEmDownDAL

0 notes

Photo

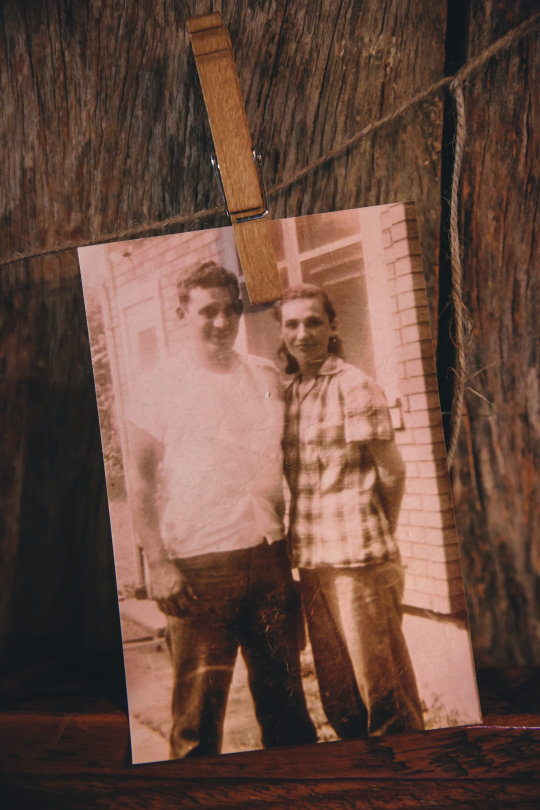

My grandmother Jo and I are next to each other in her sitting room, in my parents’ house. Mom has put the translucent mask for the breathing treatment over her face. "This scared the boys so bad!" Jo laughs through the mask's little echo, reminding herself of how my cousin's twin boys had run from her when they saw her breathing deep draughts of albuterol, the fans whirring.

She faces east out the window. It is afternoon, Thanksgiving, and the light is still warm. Most days, in between loads of laundry, she sits here and looks at pictures, reads her Bible, dozes. She plans and prays, worries about us. I have followed, or maybe have half-led her in here from the kitchen where she was folding and re-folding towels, moving dishes from stack to stack.

We sit. Jo has been staying streets down with my aunt and uncle because she has given up her room here for L., who is very pregnant; she has been playing with our son, another one of her greats, who is very much four years old. "You are ninety and you gave up your bed. That's enough heavy lifting," I say. "Just sit with me."

Down the hall pots clank while Mom and L. negotiate recipe substitutions and counter space. "It has been...let's see. It is sixty-nine years today that I was married," Jo interjects into the quiet.

"Was it?" I start. "I should have known that." I am still again for a minute. "Where was it that you were married?"

And we are off. I know the stories but it is good to hear them again, to retrace the steps she and my grandfather took--Ft. Smith, Indianapolis, Detroit. Detroit. We retrace her steps and the steps of her Arkansas expatriate sisters and all of their families. The Dust Bowl and the War; shop floors and switchboards; dances, bars; the love of the churches she and my grandfather took a long time to find. On my phone we map Ford Street, Automobile, Federal, VanDyke--in my hand a god’s view of the places she raised her girls, where they walked to church and school, and though it goes unmentioned the parking lot where my grandfather pulled over quietly to die of a heart attack while on an errand alone. “I love you more than anything in the world,” he had said to Jo on leaving the house, as he always did, but this time did not return. My mom was only sixteen. When each of us grandsons got close to twenty Jo would sigh and smile.

“How did he get to Ft. Smith from Bunch?” I ask my mom later that night, of her father. “Interstate 40,” she says, and I laugh.

Bunch is a little farther from Ft. Smith than from Tahlequah, but Bunch was Indian Country by virtue of my grandfather’s family being there. As I understand it, it was a ranching life, a country life; his was a mixed-tribe family, Cherokee and Ojibwa. We’re on the Dawes Rolls I was raised to despise. He made a journey from that life to crisply-suited manager on the factory floor of Detroit at the height of its glory. Dale Carnegie classes; dictation correspondence courses. “God, your family, and education are the three things that matter in this life,” he told his girls, “and in that order.” He did not go to college, but his girls did, and one raised me, and here I am with a Ph.D. in Religious Studies, working at a college, a second kid on the way.

A few years ago I met with a local artist in Dallas, a woman who has been much braver than I have ever even had occasion to be in telling the truth with her trade. She and I talked over a project I was hatching and her insight was invaluable and toward the end she asked what I “was” and I knew what she meant and I cried about it, after she left, after we talked about my grandfather. The big bridge of his nose, his wide cheeks, his chestnut skin: these things I see in his old photos as I see in my reflection of the windows of my house when it is night and I wonder. At what he traded for this life, what his family had already traded, at the path that took him so far from the land. And what it means for me to reckon with it.

The threat of foolish, venal appropriation is real around Native identity—personal journeys of discovery that have white folks showing up empty handed at Standing Rock; an academic landscape that one feels is almost certainly rife with little Dolezals. “I am acutely aware that my survival does not depend on the political fortunes of the Cherokee Nation,” I said to another friend recently, a poet and teacher whose indigeneity arises out of Central America, “so I am usually reluctant to say too much about this in public.”

“Except for…it does depend on that. The survival of all of us depends on that,” she corrected me.

And of course it does.

While Jo and I talk about the lattice work of street and remembered things we are interrupted by S., climbing and crashing into me, resting his feet on the soft skin on her arm and spinning down off of her couch. “Be careful of Jo Jo” I implore him, but it is hard to understand how fragile we can grow when you are built of rock and sinew like a little child is. That we need to be gentle with her now is hard for me to imagine too, because I know all about the iron core the years revealed in her as she made her way through a profession and an independent life until she retired and left Detroit to live with us down south when I was thirteen. I know all she did even then, all she carried to make our good lives possible. But it is true: we are fragile stuff, in the end, and all along.

When I think about decolonizing Thanksgiving I think about my own body and its history. Here on this couch between this old and young life I consider now the tear gas and fires; I consider How Hard We Make It. They are breaking up the encampment today; fire hoses and bright lights against the Water Protectors at Standing Rock. These people asking just for something threatening not to be built on their land, just asking for one less intrusion into their sovereignty justified by trade, by commerce, by what the country needs, by what it must extract. And I am thinking about my grandfather’s journey, about the lengths he found himself constrained to go to build a life, about what it took put us all on a trajectory such that we would be a place of peace for my grandmother all these years later, where she could sit still on the couch with her restless hands, with me. It seems to me that we have already extracted much treasure from this land. So very much.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For everyone who has daughters, who is one; who wants them to thrive

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suddenly the bass stops throbbing and the cheerleaders come out, fifteen strong, stomping and swinging. When they start in earnest, everyone in the cafeteria—the Caf—goes crazy. At their coach’s request I am standing on some chairs to take a picture of them, just after; a song they love comes on and they split before I can take it. They run yelling, heading back over to dance, a mass of black shirts and shorts disappearing around the corner. “This is a glimpse into my life,” she says, laughing. The floor trembles.

One of our student life staff is playing DJ, as he does from time to time. He was the president of the Student Government Association back in his day. In between songs he and I have been sorting things out with some student’s breach of protocol, before it becomes an issue. Guys in sweaters and slacks with careful fades take turns on the mic, hyping the crowd while he plays Montel Jordan, 69 Boyz, Quad City DJs. The theme is 80’s and 90’s music: ancient eras, basically, to these kids.

Two seniors I know begin laughing at me when Sir Mix-A-Lot comes on. “Dr. Dowdy, you look so uncomfortable!” and as they tease me I am aware even more than usual that I am a white guy in suit, but I don’t mind. One of our former trustees, a man in, I think, his seventies, takes his turn on the dance floor. He’s good. The kids roar.

The president of the college is here, it’s his party today. We’ve set up tables with games and turned down the lights and the only reason is that it’s Friday and why not be alive together, everyone up and moving if they want, or talking and sitting at tables in the Caf if they want, or whatever. It’s fried-fish as usual at the end of the week, and I can smell the warm sugar and oil from the waffle maker a table away. He and his wife, the First Lady, dance and flirt with each other. Someone posts it to Snapchat.

I see a guy from Mississippi with his friends sitting down, bobbing their heads; a student that was quizzing me about transfer credits two hours before is artfully flicking the hair around her shoulders like a minor divinity. The basketball team is carrying on across the way while a freshman with a thick and growing afro gets cacaphonous approval of his footwork from the circle. Women from BGLO’s take turns strutting to their songs; intricate gestures and whoops mark their association, patterns closed to me so entirely that I risk exoticizing my friends just to describe it. Staff and young women both join their respective crews for this. Four guys on the side are working out some steps, earnest but laughing at each other. I think I see the father of our student from Moscow is visiting us again. I see the white coat of Nurse, our most seasoned staff member, where she is seated eating with a couple of other staff and a student or two.

There is no shade of skin or body type that is missing from the dance floor. Braids, good hair, flattened, kinked, natural. One of the Latina students has just cut her hair very short, I notice.

Just before we announced this pop-up party we were in Fall Convocation: full dress academic regalia, everyone sweating. We heard a good talk, and we were encouraged to vote. “Your vote matters, in this election. Especially in this election,” the president has reminded everyone.

In the part of the day that required work, the heavy lifting part, there was just business: meetings, protocols refined, materials drafted, reports filed, data collection completed. Bricks laid, or as close as I get. At the margins of my day I was dimly aware of whatever gambit the fraudulent creep running against the former Secretary of State was trying, the stuff he is doing now to further the swindle while she languishes a little in the polls. It’s not a very comforting time.

A few weeks ago, in the chapel where our staff was responsible for the program, the vice-president of academic affairs put herself on the program. She came to the mic and took off her glasses, wiped her eyes, and sang Amazing Grace. It is the first time in over seven years she has done anything like this. The president was so visibly astonished that when he caught her eye it made her laugh mid-song.

James Cone, the couple of times I have heard him lecture, has emphasized what his parents taught him about both knowing the evil of the world he was born into and the centrality of the love that would help him survive it. He talks about barn dances and rent parties, in this context. I am on the outside of that, of this world; even here in the Caf, where I am treated like family, it is a gift I am being given, not an outgrowth of my world, my skin, the system. But being on the outside does not lessen my appreciation for the love, for these bodies in the space where they belong.

Enrollment is up at HBCUs this fall. Can you imagine why?

Some song everyone but me seems to know come on and a big slice of them are moving as one. “I should write about this,” I think, when they jump simultaneously for the first time. The floor when they hit is like a wave. The second time they jump my eyes blur from the shaking.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

INSTEAD OF A PREFACE

In the terrible years of the Yezhov terror, I spent

seventeen months in the prison lines of Leningrad.

Once, someone “recognized” me. Then a woman with

bluish lips standing behind me, who, of course, had

never heard me called by name before, woke up from

the stupor to which everyone had succumbed and

whispered in my ear (everyone spoke in whispers there):

“Can you describe this?”

And I answered: “Yes, I can.”

Then something that looked like a smile passed over what had once been her face.

-- Anna Akhmatova, from Requiem, trans. Judith Hemschemeyer

---

Can you describe this?

Can you?

0 notes

Text

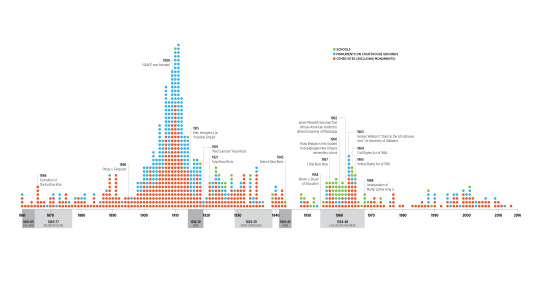

Visualizing The Red Record

Experimenting with ways of analyzing intra-textual relationships in Wells's work. Here are a couple of graphs applying the TexTexture tool to Ida B. Wells's The Red Record (1895).

Just below is a basic graph indicating conceptual nodes and density around them...

...while just below here is a graph tracing relationships among concepts more explicitly through labeling and color-coding...

...And then there's a focused look at Chapter 10, "The Remedy," which I keep coming back to:

0 notes

Photo

My dad, through the decades. Mustache era covers at least two decades.

“Another word for father is worry.

Worry boils the water

for tea in the middle of the night.

Worry trimmed the child’s nails before

singing him to sleep.”

As happens many mornings I wake up to find myself in S.’s bed. He is crying, though, which is unusual.

Nights, after L. puts him down, he typically will make it a few hours solo. As often as not, though, he eventually needs one of us in his little bed, big and quiet between the window and him, to stay down. Most mornings he wakes me up by fiddling with my nose, or my ear. “I think it’s time to get up,” he will say, or “let’s go see Mama.” Now that it’s summer here in Dallas even before seven the room is light as midday, bright with the promise of heat.

But today his nearly-four-year-old frame jerks with sadness, and wan morning light is just barely seeping through the windows’ wooden slats. It takes a minute to understand what he is so upset about, but what he is saying is “I didn’t want my dream to end.”

“Can you tell me about it?” I ask, a little groggy myself. But he is inconsolable, about the dream.

An hour or so before I had awakened myself and stared hard at the ceiling, lying next to him, listening to his breath whistling through a nose afflicted by a summer cold. I had willed myself awake out of a chaotic nightmare of a dream. The three of us trapped in hot traffic on some highway, cars crashing and smoking around us; an elephant fleeing something unseen behind us smashed things to pieces in the road ahead. But all of us soon stopped, barricaded under an overpass against the exchange of gunfire between a helicopter and police on the ground. The details from there are lunatic and specific, in the way of dreams, but it ended as my worst nightmares do—separated from L and S by something arbitrary or violent, external to us, or worse: by some stupid mistake I should have foreseen.

Another word for son is delight,

another word, hidden.

And another is One-Who-Goes-Away.

Yet another, One-Who-Returns.

I remember the four or five times my father was visibly, or audibly angry with us, when I was a child. Not because they were especially fierce, and maybe even not because they were rarities. I think it was because he apologized. He has tried to apologize to me for other things here and there now that I am an adult, too. S is only four-ish and I think I already have a list that I will try to read off to him at a diner one day, to sort things out, make sure he knows. But here there is no fault, as the play says. No fault.

My brother once observed to me that he never knew my father to do anything but give him the whole can when he asked for a sip of Coke. I remember this, seeing his head brush the car ceiling and feeling the vehicle list a little when he would lean back to hand the can over. This is an idiosyncratic little thing to mention, maybe, but it’s a sort of synecdoche of how my father thinks of things. You will understand that with great feeling, with admiration, my brother says “Man, that’s what we’re going to be like.”

So many words for son:

He-Dreams-for-All-Our-Sakes.

His-Play-Vouchsafes-Our-Winter-Share.

His-Dispersal-Wins-the-Birds.

But only one word for father.

And sometimes a man is both.

S. asks relentlessly about signs, these days. The circle-backslash of the “universal no” is endlessly fascinating to him. We were on vacation last week, and were walking past a restaurant when with great urgency he asked for me to interpret the prohibition signs on the glass door. Half-thinking, I said “That one says ‘no smoking,’ and that one says ‘no guns.’” The moment I said the latter my heart sank, and I could sense L’s distress like the pressure dropping before a thunderstorm.

“Why don’t they want guns here?” he asks.

“Well,” I wince, “people can hurt each other with them.” This satisfies him, somewhat. But the seed is planted.

“He already knows what smoking is,” she says a moment later, when he is out of earshot. “I would like to wait just a little while longer before we talk about what that is. They don’t play like that at his school, so as far as he knows, guns shoot water.” I am in agreement. I slipped.

“No guns!” he says when we pass back by, fully thirty minutes later.

It is Saturday, June 11. In the small hours of June 12, forty-nine queer Black, Latinx, and white people will be cut down by a gun in a massacre eclipsed only by Wounded Knee, states away, while we sleep three across in a hotel bed.

Which is to say sometimes a man

manifests mysteries beyond

his own understanding.

For instance, being the one and the many,

and the loneliness of either. Or

the living light we see by, we never see. Or

the sole word weighs

heavy as a various name.

I guess I am supposed to be tougher with S., somehow, toughen him up before the world does: sleep alone, do not cry, sit still when I say; wait to be spoken to, be seen as I wish you to be seen. For my part I must say I find that ludicrous. The world slaughters its innocents.

Consider the petrifying, racist harassment of the Cleveland couple whose innocent child tumbled into Harrambee the gorilla’s enclosure and necessitated the killing of that great, terrible creature, to save that beautiful, perfect little child’s life; consider the pitiless assessment of that couple whose innocent son was drowned by an alligator while splashing in shallow water at their hotel. Consider the whole range of the slaughter of innocents: the little children of Syria, or Honduras, or of any number in the living rooms within walking distance of your house who live in terror of their own fathers, own mothers, aunts or uncles.

One of the most important parts of Alfie Kohn’s Unconditional Parenting is the argument he makes that we are in no meaningful sense a child-friendly society. This may come as news to thirty-somethings whose Instagram and Facebook feeds are relentless parades of excellent childhoods publicly recorded, but it’s so transparently true of the venom we keep just within reach that I think it is nearly self-evident.

This goes beyond individual meanness, of course; it’s a point about how eager we are to defund disability insurance and other forms of support for the most helpless possible members of our society, as a whole. Despising certain kinds of parents is an economical way to revile certain kinds of children; ignoring others completely is also pretty convenient. We are good at both. Devaluing peoples lives is less emotional work, it’s less expensive for powerful people, and it’s often how business gets done. We perfected this strategy of dehumanization and emotional shortcutting with chattel slavery, and you can see its ruthless cousins in all facets of our society.

That’s what I mean by the world slaughtering the innocents: it’s not a bug. It’s a feature. So I lay down with him when he is scared, and while I do I conjure the image of my dad rubbing my back until I fell asleep, singing songs he knew by heart.

And sleepless worry folds the laundry for tomorrow.

Tired worry wakes the child for school.

Orphan worry writes the note he hides

in the child’s lunch bag.

It begins, Dear Firefly….

I happened to show S. icons of Jesus of all kinds today, on image search. Jesus the Liberator with black skin and hair in tight curls; Jesus of the First Nations with high cheekbones and long black hair; Jesus as a Black and Native woman; Jesus pulling apart barbed wire to stare out alongside other prisoners. He asks what a cluster of photos up in the top left of the screen is. It’s the crucifixion.

How to respond to this? I think of the police seeing more dead bodies in that night club in one night than they had in ten years on the job combined, or of the little boy face down in the sand on the shores of Turkey, or of the blankets they pass out at freezing detention centers for minors who have fled Honduras alone; of all the bereft fathers and mothers and friends staring up into the sky and hoping that they can rouse themselves from this dream, but knowing it is not a dream, knowing that no tenderness can rescue them from the chaotic reality in which they are enmeshed. So today all I can say is, “that is a sad part of the story.”

“Is it a storm?” he replies.

“Yes,” I say. “It is a storm.”

What I wanted to say the other day, after he woke up crying, was “all we can do is tell each other about our dreams, buddy. That is all we can do, and sometimes, it is enough,” but that is speaking in code, and I know it. I tell L. that this thought passed through my mind, and she laughs patiently.

poem by Li Young Lee: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/li-young-lee#about

0 notes

Photo

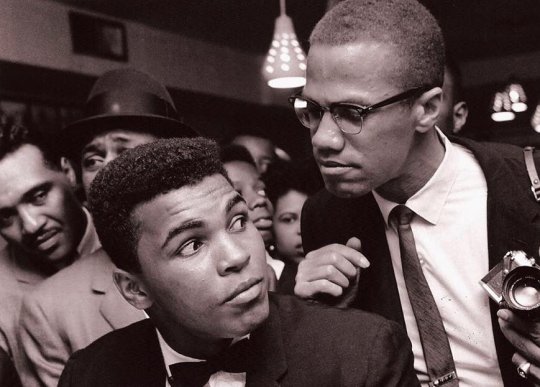

@BroderickGreer posted this photograph a little bit ago; I don’t know its provenance, but I love it.

I was just fifteen years old and mostly clueless in 1996, when Ali lit the Olympic cauldron in Atlanta, my hometown. Even then I felt a sense of awe when he, tremulous, raised the torch a second time before lighting. I don’t know what I thought then, really: was I sensing irony in this nearly invincible man so visibly afflicted? Was I feeling impressed with his triumph over his body?

If I did think those things, I was wrong. What we saw, what he chose to share with us at so many moments, from Rome to Kinshasa to Atlanta, was the same all the way through: a person completely alive to and at home in his own body, his very body. So ferociously, deliciously at home in its blackness, its strength, its tremors and surprises; unsurpassed footwork, his face to the ground in prayer. What a gift to the world this whole life has been. Lighting the cauldron, embracing him as the best of us: what a way to describe ourselves, to describe our hopes for who we might become.

0 notes

Photo

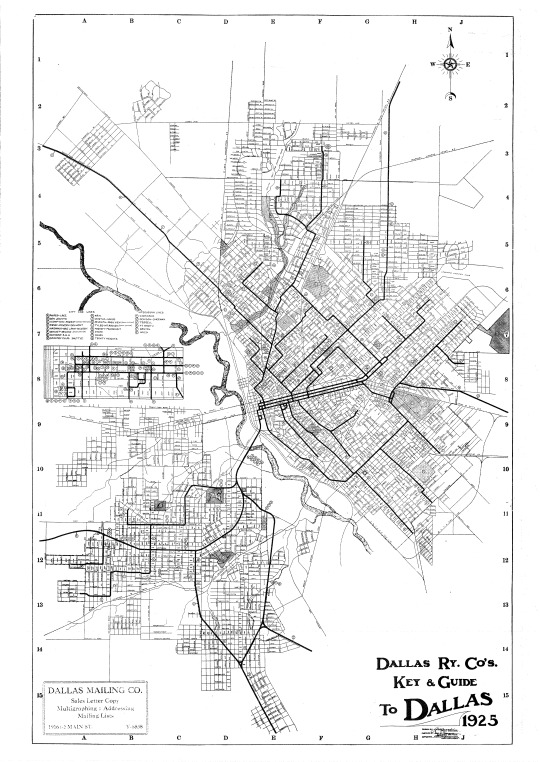

Streetcar lines; blue veins beneath the skin. All the way up to State-Thomas, even. Yes, we did tear them out with a sense of urgency. We did.

0 notes

Photo

Today my brother sent me these pictures and said, “Some very strong and strange nostalgia here at this games shop...”

I started to write him back a short text about when we lived in Pennsylvania, playing in the basement together, and before I knew it I was like 800 words in and was crying at my desk. He told me I should put it online, so here it is:

Green chair and card table; magnavox tv and grey recliner. Drop ceiling and the long staircase into the basement. You painted on the chair. Maybe we both had stations down there? There was a desk against the far wall, a light brown stain and a white phone resting on it.

Upstairs dad showed me the G chord on the Martin Dreadnought but I never took to it, not like you. We both took piano lessons and dug tunnels in the backyard during the 93 blizzard.

I never played more than one or two actual games with the Warhammer figures but I thought about them endlessly, modified them, created storylines. I remember the intricacy of the designs I tried to paint on the elephantine shoulder pads of the space marines.

We played outside. The creeks and small forests around brandywine national battlefield, a bookstore in the woods somewhere we drove hours to once. Forsythia in bloom, impossibly bright showers of yellow along the road. Dad taking us to Blue Hen Comics, or up to Granite Run Mall for some other comics store. The edge of all that half-realized adolescent violence, sublimated sex, the world of spirits invisible but so real, it seemed, to everyone we knew. Right then, though, just us playing, drawing, painting, sometimes actually together. We were just boys.

I don't want to go back really, but i wish I could remind myself even once to take it in and be grateful for it in all its awkward glory. It was good to grow up with you. I had it very good.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

On Rey’s Humanity in Star Wars: The Force Awakens

This post contains some mild spoilers for Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Mostly it contains me arguing that Rey is in fact written as a human being with recognizable frailties. It is not a review, it is not a thoroughly-linked engagement with everyone who has written about this huge mass consumer product in the last week; it’s a cold take, I hope, just trying to piece together something that seems important to me.

She has been on her own a long time, and has learned the required skills to fend for herself. Because of her loneliness and her skills it is unwelcome, even a violation, when a well-meaning, potential ally grabs her hand without permission in the middle of a fight. “Why do you keep taking my hand?” she exclaims, infuriated. Only after he has accepted her hand when he really needed it—knocked back, winded—does their trust begin to build.

She is offered a job, a job she really would love and thrive in—a job that would be a deliverance from the drudgery in which she is currently constrained to work for survival. She turns it down. Cuts off the conversation. Family obligations, even the mere vapors of family obligations, make it impossible to launch into the unknown.

She holds her own in a contest of strength and skill against a man her age. The rival, a man, offers to explain her emerging power to her. “You need a teacher,” he says. Earlier the same man strapped her to a chair and tried to take things from her without her permission. Impassive, serpentine, he promised the blank and simplest sort of violence: “You realize I can take anything I want.” Mansplaining’s two faces.

As with other heightened worlds in fantasy and science fiction, in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, text and sub-text often merge. A fight for dignity is often really a fight; a comrade in arms is often really a comrade in arms; the pull of good and evil forces elemental to the universe are actually the Force. The internal and external threats that shape Rey’s narrative—the paralyzing family obligations keeping her off the Millennium Falcon’s crew, the unwittingly triggering allyship of the good-hearted, clumsy Storm-Trooper Finn, the luridly cruel mansplainer Kylo Ren—are existential threats to her possible futures. They are threats to her autonomy, her sociality, her delight and capacity for responsiveness; threats to her dignified inclusion in a community of equals. These threats she faces are real, the realest kind of threats.

We see how isolation and fear do their work on her moral capacities. She at one point has a chance to trade the freedom of a new, especially vulnerable companion—the droid BB-8—for a little more stability. She catches her breath. She almost scoops up the ransom in her arms and leaves the little creature behind. That is what surviving can do to you. But compassion stops her. Compassion is the harder choice, and it is hers; and it is what leads her into the path of and adventure that has been awaiting her all the time, to the aged rogue Han Solo and his co-pilot the Wookie Chewbacca; to Finn, whose own compassion broke his heart and put him and Rey on the same trajectory.

We see how abandonment and trauma threaten her capacities for community. Her strength makes her a better fighter, a better colleague; it makes everyone around her better, because it spreads the struggle out to the very edge of everyone’s contiguous competencies. But it also has its origins in an abandonment that makes actual friendship, actual earned allyship, dubious to her, surprising. This abandonment is a deep trauma that threatens to undo any new family of choice, to undermine the capacity for trust and loyalty. When she is later captured, she escapes on her own; she is delighted but shocked to discover her friends have returned to find her. She can scarcely believe that she has so quickly acquired a family.

The Force Awakens has problems, but the notion that Rey has no actual struggle to overcome is not one of them, because her struggles are pretty obviously the struggle that lots of little girls have.

I say “lots” to resist being too generic here, because it is true that whether and when little girls struggle with actualizing their power will have a lot to do with context--power to what, over whom, in what community, with what color skin, etc., etc. Especially if little girls have the freedom to consume mass media on a regular basis and become discerning consumers of it, they may have lots of occasions and encouragement to exercise power. Like anyone who does exercise power they may do so badly, and against others more vulnerable than them. So just asserting Rey is a good role model for girls, or something else equally bland, is not very helpful, because it ignores the living texture and power differences and everything weird about individual girls, boys, and sexes betwixt and between.

But it is worth saying that many girls, and for many of various sexes whose expressions of gender do not match a fixed trajectory, asserting oneself and asking for help will be a big challenge. Even ones who are lucky enough to find themselves in a part of the galaxy where equal dignity is a real, if fragile, possibility, where the allies are really allies, where there is an active Resistance, the struggle will be real. For so many little girls it will be their struggle to become themselves in a world that for the most part despises their self-knowledge. It will be their struggle to play after they turn nine. It will be their struggle to keep raising their hands in science courses. It will be their struggle to read all the kinds of books they want to read and are curious about. It will be their struggle to write all the kinds of books they want to write and are curious about.

So as a critical person, as a fan, and as a cis/hetero man, I’m writing tonight on Christmas vacation while my nieces sleep upstairs to sound a note of caution about any overheated critique of Rey’s self-actualization that does not take our galaxy into account. I write as someone probably as clumsy as first-act Finn in my allyship, but I suggest to you that it may be Rey is especially for the ones whose struggle is against collapsing into themselves, collapsing into the dumb expectations of the world, collapsing into the loneliness, the isolation of survival without help. The theme of Rey seen from the horizon of our galaxy is a struggle against internalized despair; the despair itself constituted by the isolation, co-optation, and deprivation that are the hallmarks of successfully implemented patriarchy. A hero who overcomes that sort of temptation to despair is a gift to little girls, I think, and to little boys too, for all kinds of reasons.

I think she’ll be a gift to mine. I have been watching my three year old son try to figure out a balance bike the last few days. Stumble, walk, stride, glide a little. Fall over. I make myself pause when he tumbles, wait to see if he can gather himself, pick himself up; wait to let him ask for help if he needs it. Sometimes he dances so hard, spinning in circles, that he falls over. Sometimes he apologizes when he is learning new things. He doesn’t do it too often, and I don’t think he means it too much. I hope he doesn’t. I hope that when he is in the midst of trying, and he’s on his heels, that he closes his eyes, breathes deep, remembers what surrounds him. And that, however he has already been bruised, he then opens his eyes and leaps back into the fray.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our own maps

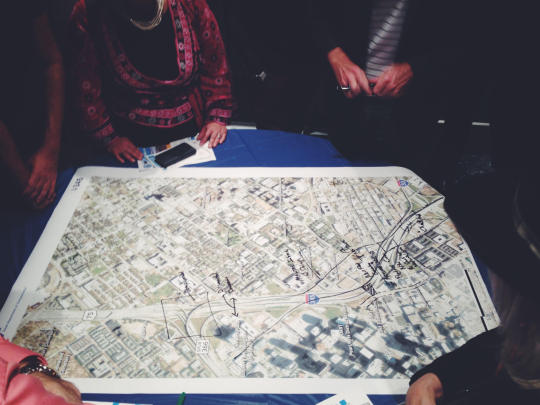

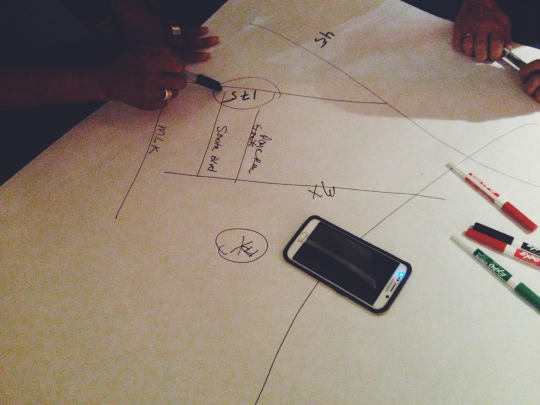

“I’m just a little disoriented, because I’m not seeing our neighborhood on the map,” says a woman who has made a very short trip from her home near Fair Park to this public meeting at Dallas’s African-American Museum. She is a black woman; our group facilitator, as is often the case in these situations, is a white woman, and is very much trying to work out the off-map issues. But without a way to talk about this woman’s street the exercise really does not seem like it is going to work.

The atrium of the museum is just about at capacity. About sixty people have been rotating among four stations in twenty-minute shifts; we are milling about facilitators. This public meeting is the third of its kind, and among nearly eighty similarly structured feedback sessions with other organizations and community groups organized by the Texas Department of Transportation (TXDOT) branded as the City’s Master Assessment Process (CityMAP). Facilitators wait with sharpies, white paper on easels, gigantic maps laid out against blue tablecloths. Each station focuses on a different blown-up section of Dallas highway: the Canyon, the Zang Curve, I-345, I-35E where it slices the old flood plain that is now the Design District off away from Uptown. Workshop participants are grouped loosely, just based on when we showed up and signed in, but patterns have begun to emerge in the conversations. Oak Cliff people wonder why it is so hard to get bikes from one trail or thinly protected bike lane to another, while Fair Park people point to stressed infrastructure and tracts of land pinched into disuse and danger; new urbanists hope we depress some roads and kill others altogether, while well-dressed commuters wonder how they and trucks are going to get from north to south and back if this or that highway disappears. People suggest decks here, lowering highways there, make friends, get on each other’s nerves. At one point some candidate’s representative snuck control of the moderator’s microphone to tell us why the whole exercise is a waste. People turned back to their tables as he spoke on; a woman filmed him on her phone.

There is a forensic dimension to analyzing closely these great asphalt and concrete gashes through the city. You see where the thick, imposed boundaries have spawned parking spaces and empty lots, where they churned up dense neighborhoods or flat out replaced existing rail lines. The effect is a very close examination of a wound.

Patrick Kennedy of Walkable DFW has written a very good piece for his D Magazine blog about CityMAP, a positive one, and floated his own ambitious plan. It is worth reading if only because he argues for a deeply intuitive thing that seems on the face of it, impossible: re-stitching together the neighborhoods of Dallas, burying or eliminating the big roads. It’s a powerful argument. For most of the people here, though, the contribution they are making is valuable precisely because it is not a comprehensive vision: they are bringing in an understanding of the human scale of this undertaking. These are the experts who know where the traffic bottlenecks, where you have to put your bike on a sidewalk, where it is too hectic to walk.

CityMAP aims to bring in multiple stakeholders to determine the re-shaping the master plan for the central highway arteries around Dallas. That is the theory, anyway. So if you don’t see yourself on the map…well.

The facilitator almost seems relieved when an earnest man standing next to the woman who can’t find her street suggests repeatedly that we turn the paper over and draw the map so that the west and south of Fair Park actually is included. Together the three of them flip over the paper and get their phones out to check their rough sketches of interstate 30, the oval Cotton Bowl stadium at the center of Fair Park, and the rows of stately old houses sandwiched in between Dade Middle School and the MLK Community Center. She explains with nuance and detail where the roads break up social landscapes, keep people from maintaining safe pedestrian itineraries. The facilitator writes down the comments in the marker color-coded for "challenges."

Whatever comes of these discussions, it is instructive that when conversation threatened to break down, what made the difference was removing the barriers to this woman making her own map. And, of course, it was a map she was ready to draw.

2 notes

·

View notes