Video

There's a few workplace games emerging at the moment.

Downloaded this today, and enjoyed 'Reshuffle' at Dare to be Digital a couple of weeks back.

Good to see games satirising the mundane grind, bureaucracy and internal politics of the white collar sweatshop.

The Firm is available here:

itunes.apple.com/ch/app/the-firm/id883108531?mt=8

Reshuffle Dare Trailer:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9wEZZgH7YNM

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weekend Cocktail #1 – The Frais Sauvage

After a week of bashing out the PhD, it was time for a cocktail.

This week I thought I'd try this recipe from 'Speakeasy', the wonderful book from NYC's Employees Only bar.

EO make theirs with demi-sec champagne but we prefer things a little drier so I opted for a vintage brut Cava instead. I made my own wild strawberry cordial with late Suffolk strawberries, a little water, vanilla extract and lemon zest, boiled up then simmered for 30 mins. My homemade simple syrup is 2:1 ratio so I cut the EO amount in half.

Ingredients

2 oz Vintage Brut Cava

1.25 oz Tanqueray Export Strength Gin

0.5 oz Wild Strawberry Cordial

0.5 oz Lemon Juice

0.25 oz Simple Syrup

1/2 Strawberry for garnish

Process

Chill a coupe glass (5 oz minimum) in the freezer

Remove glass and pour in two ounces of chilled Cava

Put remaining liquid ingredients into a mixing glass

Add plenty of large cubed ice

Attach the shaker

Shake hard for ten seconds

Pour the cocktail over the Cava

Garnish with the strawberry.

0 notes

Text

How Does It Feel? Beyond Genre Towards Analysis of Experience

This paper was originally written and published for the Media Education Journal 52. It reinforces that extant media theory is not always sufficent to analyze non-linear, co-authored experiences with little or no narrative, such as Flower by ThatGameCompany, and serves as an introduction to the Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetic framework for analyzising and designing digital games.

ABSTRACT

Digital games consist of unique elements that clearly distinguishing them from more established screen-based media such as film and television. These elements, commonly known as mechanics, create non-linear and co-authored experiences giving rise to dynamic patterns of play producing aesthetic experiences that elicit emotion from the player. Existing genre analysis paradigms imported from more established disciplines may be useful to analyse games that heavily employ film or literary conventions, or which are derived from particular works or extant genres such as Film Noir. However, understanding how digital games – experiences often comprising a core of asymmetrical gameplay that gives rise to emergent narratives augmented by a representational shell with little or no characters, dialogue, or recognisable genre conventions – create meaning poses a distinct challenge for these frameworks. This paper identifies how game studies has developed concepts and methodologies to enable constructive critical analysis of game experiences for scholars and designers alike.

INTRODUCTION

The prohibitive costs and high risks of AAA game development, the rise of the mobile and casual sectors, and an increase in digital downloading of games via platforms such as Apple’s App Store or Valve’s STEAM [Brightman, 2012] means start-ups and small game studios are increasingly developing compact games for a changing marketplace. Many of these games, such as Rovio’s Angry Birds, have a achieved considerable success through giving primacy to gameplay over narrative or rounded characterisation.

Digital games without characters or structured narrative are not new. At the dawn of the medium, primarily as a result of technological limitations, games such as Spacewar!, its failed commercial derivative Computer Space, and the seminal Pong, relied on simple mechanics to produce a vast and engaging dynamic pattern of gameplay. All three “exhibit a basic asymmetry between the relative simplicity of the game rules and the relative complexity of the actual playing of the game” (Juul, 2005, p.75) and as a result can be regarded as emergent in nature.

Emergent gameplay results in high replay value as the inherent asymmetry between rules and dynamics ensures no two games are the same; a necessity in the arcade where games produce a return on investment by encouraging players to continually spend money. In addition simple rules led to simple instructions. Perhaps the most famous sentence in digital game history is the instructions for Pong: ‘Avoid missing ball for high score’. This simplicity helped make a new, and possibly intimidating, medium accessible by virtue of being simple to understand and play. Add the elegant if rudimentary representational shell, and it is unsurprising Pong has achieved constant popularity throughout its forty year history.

It would be erroneous to describe emergent games as totally without narrative, but the fictions enjoyed are fundamentally different to those usually enjoyed in a film or television text. These fictions are also emergent, not pre-structured or pre-programmed, instead taking shape through the gameplay experience (Jenkins, 2004, p.14). Even as technology has developed to allow the design of increasingly photorealistic games with vast structured narratives, LA Noire or Heavy Rain for example, games that rely primarily on engaging gameplay – the balanced combination of mechanics and dynamics – have continued to thrive. It may even be argued that such games constitute a ‘purer’ gaming experience, uncluttered by costly attempts to replicate the Hollywood blockbuster experience driven by deep-seated ‘cinema envy’ amongst game designers [Jenkins, 2005].

THE STRUCTURE OF DIGITAL GAMES

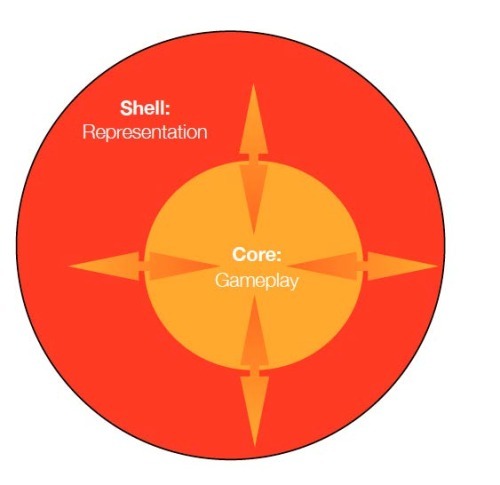

When seeking to analyse any digital game it is first useful to uncover its underlying structure. The question of ‘what a game is?’ has yet to be answered, and the scope of this paper fortunately does not extend to addressing it. However, Mayra (2008) suggests there are certain structural features that make it easier to distinguish between the different forms of meaning-making at work within any game. These distinguishing features are the two layers that constitute the concept of a game: the core and the shell.

Figure 1. Mayra’s dialectic of Core (gameplay) and Shell (representation) in the basic structure of games.

The core equates to the ‘gameplay’ layer of the game, comprising the mechanics that result in the dynamic patterns of play underpinning the play experience. These are both abstract – consisting of a unique system of interactions and relationships that remain when the aesthetics, technology, and story are removed (Schell, 2008, p.130) – and transferable; meaning this abstract structure will continue to function and give rise to same dynamic patterns of play regardless of the representational shell it is attached to. For example, Monopoly would be basically the same game regardless of changes in the aesthetic design of the pieces, cards, or board, so long as the designed core of ‘Monopoly mechanics’ was in place.

At this juncture it is important to point out that while game designers carefully craft a meaningful system of play, they cannot directly design a play experience itself. That only occurs when a player interacts with the designed system. And due to variables in the way the player interacts – cognitively, functionally, and explicitly – this experience will differ. Game designers design the structures and context in which play happens – indirectly shaping player experience – through creating a space of possibility for future action to occur (Salen and Zimmermann, 2004). The experience is unique for each player – particularly in emergent games less hindered by linear requirements of a pre-scripted narrative – and in addition to the designed mechanics, variables related to programming code, hardware, and controls also impact the final player experience in digital games.

Enveloping and dynamically interacting with the core is the shell, or representation. This contains all the semiotic richness modifying, containing, and adding significance to the core gameplay experience (Mayra, 2008). This element is also sometimes referred to as the presentation, and is understood as the expressive and representational element of digital games, dominated by moving images and cinematic techniques, augmented by sound (Nitsche, 2008). It is the game as a system of signs and cues, both visual and audible, that open up and extend possibilities for narrative layers and cultural context. It is here that existing theory – aesthetic, literary, media, cultural etc. – can most usefully be deployed for the analysis of digital games. Many scholars have made use of extant theories to analyse the representational aspect of games, but before this embarking on this analysis the scholar must consider the core.

MECHANICS, DYNAMICS, AESTHETICS

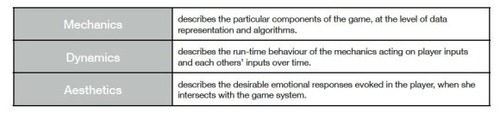

The Mechanics, Dynamic, and Aesthetic (MDA) framework is a formal approach to understanding games. Developed by Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc and Robert Zubeck between 2001-2004, it views digital games as artefacts created within an iterative design methodology, and therefore uses the same approach to analyse them. The authors specifically suggest that iterative analyses support understanding of the end result of game design to refine its implementation, and help analyse the implementation to refine the end result (Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubeck, 2004a, p.1). In particular the authors suggest that scholars must learn to recognise the interactions and interdependencies present in digital games that “create complex, dynamic (and often unpredictable) behaviour” (2004b, p.1) before they can reach informed conclusions about the nature of the experience generated.

The MDA framework focuses on the game’s core, stressing that fundamental to the methodology is the notion that games are more like artefacts than media. The authors suggest “the content of a game is its behaviour – not the media that streams out of it towards the player” (2004c, p.2). The framework argues that games are designed systems that build behaviour through interaction, and in order to understand this behaviour it advocates concentrating on the mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics of the experience.

Figure 2. The Components of the MDA Framework.

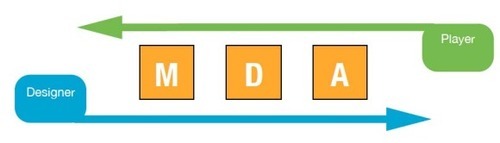

MDA treats the relationship between the designer and the player as a ‘two-way street’, with each experiencing the game from a different perspective. The designer crafts a set of mechanics expected – when the player interacts with them – to give rise to dynamic patterns within the game system, resulting in a particular aesthetic experience. These three layers of Mechanics, Dynamics and Aesthetics are mutually dependent. When undertaking analysis of a game it is beneficial to consider both the designer and player perspectives, but to understand and interpret the player experience scholars and researchers start with aesthetics. This starting point also allows designers to focus on experience-driven rather than feature driven design (2004d, p.2).

Figure 3. Designer/Player Experience

Aesthetics

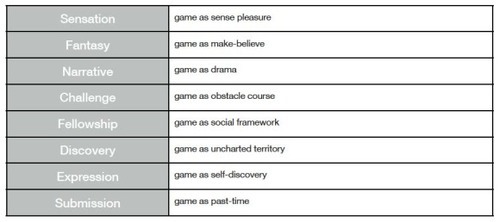

The MDA framework use aesthetics as a layer to capture the subjective experience of the player, and the emotional response or pleasure the game is designed to evoke (Aleven et al, 2010, p.70). It outlines a non-exhaustive taxonomy of eight different aesthetics in an attempt to further define the vague and highly debated concept of ‘fun’.

Figure 4. MDA Experiences

When deploying MDA it is usual to first identify what aesthetics the player experiences, or what the designer wants them to experience. By applying these aesthetics to the games Charades, Pong, GrandTheft Auto IV, and FIFA13 it can be suggested that they each create the following combinations of aesthetic experience:

Charades: Fellowship, Expression, Challenge

Pong: Challenge, Sensation, Narrative, Submission,

Grand Theft Auto IV: Discovery, Narrative, Challenge, Fantasy, Sensation, Submission

FIFA13: Challenge, Fantasy, Expression, Sensation, Fellowship, Narrative, Submission

Dynamics

These are the behaviours that result when the player interacts with the designed mechanics during play. Unlike aesthetics there is no taxonomy of game dynamics offered by the MDA framework. Therefore it is up to the scholar or designers to invent the terms and concepts needed to characterise the dynamics of a given game (Aleven et al, 2010b, p.71). Dynamics are the place where choice meets: the choice of mechanics implemented by the designer, and the choice of action by the player. These choices create a feedback loop that influences behaviours and further choices within the game system. For example, if the designer wants to achieve the challenge aesthetic they will consider dynamics that may elicit this aesthetic, such as opponent play, time or resource pressures. They will then attempt to craft and implement mechanics that could give rise to this dynamic e.g. a two-player game, a timer, or finite lives or health. A game’s dynamics are the behaviours that result within the game world from actions sanctioned by the games mechanics.

Mechanics

Although what actually constitutes mechanics is contested by game scholars and designers alike, the MDA framework considers them to be “the various actions, behaviours, and control mechanisms afforded to the player within a game context” (Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubeck, 2004e, p.4). Using this definition we can extrapolate that mechanics include the foundations of a game: the objects, attributes, states, rules, actions, goals, and control options available to the players. When analysing a game the scholar (or designer) can work backwards from a particular aesthetic, to the dynamics that created it, to the mechanics that support that dynamic. It is worth remembering that the designer can only directly control the mechanics of the game. However, the same process of deconstruction that allows the game scholar to uncover the design choices that may have led to a particular aesthetic outcome also allow the designer to articulate aesthetic goals, and make reasoned choices at a mechanical level to support that outcome (Aleven et al, 2010c).

CASE STUDY: FLOWER

Some contemporary game designers are attempting to explore the unique possibilities of digital games, focusing on the design of experiences rather than features, applications, or narrative (Mayra, 2009, p.6). Perhaps at the forefront is Jenova Chen, Creative Director of That Game Company. Founded in 2006 while Chen and co-founder Kellee Santiago were students at the University of Southern California, the studio has produced a series of critically-acclaimed games that prioritise the player’s emotional experience over complex mechanics, or a clearly defined linear story with deep characterisation and dialogue. Their most recent game Journey was notable for an unnamed protagonist who could emit only a musical note of extendable duration, and containing no dialogue or displayed text except the game credits.

Released in 2009 Flower is described as “our video game version of a poem” (That Game Company, 2012). The gameworld of Flower consists of six levels, progressing from representations of a pastoral meadow through sublime landscapes increasingly populated with signs of human civilisation such as wind turbines, until the player reaches the final urbanised cityscape. The game is emergent in nature with asymmetrical gameplay; indeed the mechanics are almost as simple as Pong. It is accompanied by a dynamic score that corresponds to changes in the gameworld with appropriately adjusted instruments and tones in order to reinforce emotional responses in the player. Gameplay consists of the player controlling the wind as it blows a single petal, the petal can be steered by tilting the Playstation 3 controller to alter the pitch and roll, and by pressing one of the pressure sensitive buttons the player can increase the wind and make the petal move faster. Other flowers are visible; approaching them with the petal brings them to life, adding more petals to the original, creating a tail and changing the landscape in the process, usually by adding vibrancy or opening new areas. The game foregrounds the environment and its exploration, achieving a calming, rhythmic quality unhindered by tension. The experience enjoyed by most players has led the game to be described as ‘Zen Gaming’ (Russell, 2009).

APPLYING MDA TO FLOWER

The Core

As previously discussed the first-step in analysing an emergent gaming experience such as Flower is to separate the core of the game from its representational shell. It is necessary to temporarily discard the audio-visual presentation in order to truly get ‘under the hood’ and see what makes Flower the experience it is. The presentation can be revisited and analysed later in the process.

It should be obvious that in order to analyse any game from a scholarly perspective utilising the MDA framework, it is imperative to play it first. Only after you have experienced the game is it possible to categorise it using the taxonomy of aesthetics. After playing through Flower three times, the author categorised his experience as follows (in order of primacy):

Flower: Discovery, Sensation, Expression, Challenge, Narrative.

To understand how these aesthetics may have been achieved it is now necessary to look back at the possible dynamics and mechanics at work to create these aesthetic outcomes during play.

Discovery

For discovery to exist as an aesthetic outcome, the game must provide both space and time for the dynamic of exploration. Flower achieves this through a relatively open-world level design and the mechanics of movement – the pitch and roll that control up/down and left/right – coupled with control of the wind that enables forward motion at variable speeds. The absence of mechanics such as a timer, opponent play, or a scoring system means the dynamics of time-pressure, conflict, and resource acquisition are almost completely absent. This allows the player to calmly explore the gamespace at their own pace and rhythm. And it is this pacing and rhythmic quality that perhaps makes the game feel most poetic. In addition, the ‘collecting’ and ‘pollinating’ mechanics explored in more detail below also augment and encourage spatial exploration.

Sensation

The mechanics of ‘collecting’ and ‘pollination’ encourages the player to seek out and collect more petals in order to experience the dynamic of changing the playscape by increasing the colour and vibrancy, starting a wind turbine, or allowing access to a new area as a reward when certain groups of flowers have been pollinated. This change in the presentation signifies progress through the level, providing a visual and audible reward – complimented by haptic rewards through the controller – to the player. It clearly displays how a designed mechanic gives rise to a dynamic feedback loop that in turn provides changing sensations in reaction to player input; this in turn keeps the player making inputs and thus continue to be engaged with – and changing – the game. The success with which the designers of Flower achieve this sensation exhibits how well integrated and designed the games mechanics and dynamics are with its representational shell.

Expression

The achievement of the expression aesthetic is closely integrated with the sensation aesthetic within Flower. Expression comes from dynamics that enable the player to leave their mark on the game, whether through building, constructing, customising or changing (Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubeck, 2004f, p.3). As the player explores and progresses through the game they leave behind a changed landscape; a grassy pasture becomes rich with blooming flowers, wind turbines are activated, and a city returned to nature. To augment this the menu screen also changes as each level is completed, becoming increasingly vibrant.

Challenge

Challenge exists in Flower but is fairly low-level in comparison to many digital games. The game is not designed to be difficult. Mastering the simple movement mechanics and understanding the ‘collect’ and ‘pollinate’ mechanics provide the biggest challenge to the new player. The ‘crows-nest’ dynamic – taking your trail of petals to a high altitude in order to identify where needs pollination – is also left to the player to figure out, although it is hinted at by the camera. The game provides no detailed instructions, relying on the player to intuitively deduce what needs to be done. The level of challenge this represents may depend on the player’s own proficiencies, but whatever these are the game is designed to keep the player within Csikszentmihalyi’s ‘flow channel’, somewhere in the narrow margin of challenge that lies between boredom and frustration (Schell, 2009, p.119).

Narrative

For the game to achieve the narrative aesthetic under the MDA framework it must be seen to achieve the dynamic of dramatic tension. Flower does have a gentle dramatic arc caused by the incremental increasing of difficulty when implementing the mechanics. This is augmented by changes in level design, making the later levels more difficult for the player to navigate and orientate themselves in. Again this is closely integrated, and reinforced, by changes to the representation. In fact much of the dramatic tension is achieved by the game’s representational shell.

The Shell

Once the analysis of Flower’s shell is complete, the scholar can then embark on deconstructing the game’s representational shell. As mentioned earlier it is here that existing paradigms from more established theoretical disciplines can be deployed most efficiently. It is beyond the scope of this paper to perform a full textual analysis of the representational shell of the game, but useful areas for exploration might include using aesthetic theory to examining the interplay of images within the visual representation; exploring the polysemic nature of Flower as an incomplete fictional world by seeking to identify themes and make intertextual connections to similar works in different media; exploring the spatial qualities of the game through the figure of the flaneur to identify the psychological aspects of the designed environment; or investigating the idea of using an environment as the primary character or protagonist in a work of fiction.

CONCLUSION

Digital games are designed experiences comprising two-layers, the core and the shell. While it is possible to utilise established media studies paradigms to analyse games as media, these are not sufficient to gain an understanding of the experiential nature of digital games. The MDA framework has been an influential and useful output of games studies as a distinct discipline. Its strengths lie in an ability to analyse and interpret the player experience and uncover design choices that occurred to produce it. By separating out the core from the shell, deconstructing the core using MDA and the shell with theory from the extant media and cultural studies toolkit, before integrating the findings; it is possible to perform an analysis of a digital game that does not suffer from being overly reliant on thinking better suited to other media while highlighting the very reasons digital games are unique from these media.

REFERENCES

Aleven, V., et al. (2010). Toward a Framework for the Analysis and Design of Educational Games. [Internet]. Available from: http://matteasterday.com/Matt_Easterday/Reseach_files/Aleven,%20Myers,%20Easterday,%20Ogan%20(2010).pdf [Accessed 20th October 2012]

Brightman, J. (2012). [In Press]. Digital Game Sales in US Grew 17% during Second Quarter – NPD. Games Industry International. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2012-08-08-digital-game-sales-in-us-grew-17-percent-during-second-quarter-npd [Accessed 20th October 2012]

Hoggins, T. (2009). [In Press]. Flower Video Game Review. The Daily Telegraph. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/video-games/4611024/Flower-video-game-review.html [Accessed 21st October 2012].

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M. and R. Zubeck (2004). MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research. [Internet]. Available from: https://sakai.rutgers.edu/access/content/group/af43d59b-528f-42d0-b8e5-70af85c439dc/reading/hunicke_2004.pdf [Accessed 11th October 2012]

Jenkins, H. (2004). Games as Narrative Architecture. In: Salen, K. and E. Zimmerman, eds. (2006). The Game Design Anthology: A Rules of Play Reader. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, pp. 670 – 686.

Jenkins, H. (2005). Games: The New, Lively Art. [Internet]. Available from: http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/GamesNewLively.html [Accessed 20th October 2012]

Juul, J. (2005). Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Mayra, F. (2008). An Introduction to Game Studies: Games and Culture. London: Sage Publications.

Nitsche, M. (2008). Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Schell, J. (2008). The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Salen, K. and E. Zimmerman. eds. (2006). The Game Design Reader: A Rules of Play Anthology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Salen, K. and E. Zimmerman. (2004). The Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

LUDOGRAPHY

Atari Inc. (1972). Pong. Sunnyvale, CA: Atari Inc. (Arcade).

Bushnell, N. and T. Dabney. (1971). Computer Space. Mountain View, CA: Nutting Associates. (Arcade).

EA Canada. (2012). FIFA 13. Redwood City, CA: Electronic Arts. (PS3, PS Vita, XBox 360, Windows, Mac OSX, iOS, Android, Cloud-based, et al).

Quantic Dream. (2010). Heavy Rain. Tokyo: Sony Computer Entertainment. (PS3).

Rockstar North. (2008). Grand Theft Auto IV. New York, NY: Rockstar Games. (PS3, XBox 360, Windows).

Rovio. (2009). Angry Birds. Espoo: Rovio Entertainment. (iOS, Android, PS3, Xbox 360 et al).

Russell, S. et al. (1961). Spacewar!. Cambridge, MA: Unpublished. (PDP-1 Mainframe).

Team Bondi. (2011). LA Noire. New York, NY: Rockstar Games. (PS3, XBox 360, Windows, Cloud-based).

That Game Company. (2009). Flower. Santa Monica, CA: Sony Computer Entertainment America. (PS3).

0 notes

Text

Who Let the Dinosaurs Out? Digital Games and Computer Science Obsession

It was the article in Develop that did it. My discomfort with the media mono-narrative about the importance of Computer Science in education, and in particlular the UK game industry, became serve irritation in three seconds flat.

I'm aware of the importance of Computer Science. But to make great digital games requires the succesful integration of art, design, and science – a Renaissance model if you like. Unfortunately Jamie MacDonald, Senior VP at Codemasters, stated that anyone wanting a job in the games industry needs to get a Computer Science degree, and that undergarduate games degrees were a scandalous waste of money. Mr. MacDonald, who did a BA in Philosophy, went on to say:

"It has been a scandal really the amount of money that’s been wasted on undergraduate courses on kids that will never get a job in the industry.

In the console world – maybe I’m old fashioned – I like people to have really good first degrees from good universities in computer science, then they can do a gaming course.

Let’s not forget that we are competing in a global industry so we have to compete with the best in the world. We can’t do that with people who are not up to it."

As I always say, why bother with reasoned and supported statements when you can make sweeping generalizations? Never mind the great courses at universities such as Abertay, Norwich University College of the Arts, and a few others – according to MacDonald all games courses are terrible. So, in the true spirit of MacDonald's missive, here's my response:

It's a scandal the way the UK games industry is run by men (yes, men) so lacking in vision. Current senior executives are relics of a model that relied on serendipty and nepotism. Now they've had their careers and made their money they want to tell everyone 'how it is'. Unfortunately they don't know how it is, as they're still living in 1996.

It's unbelieveable these men are still employed, after failing to predict so many sector changes over the past few years. The coming of social gaming – in particular Facebook games – left these dinosaurs playing catch-up and lay-off. But, like the bankers, they are still rewarded for failure.

This is a crucial time for the future of the UK games sector, facing increased competition from both the developed and developing world. It just can't afford to tackle these challenges with the wrong people in charge.

1 note

·

View note