Text

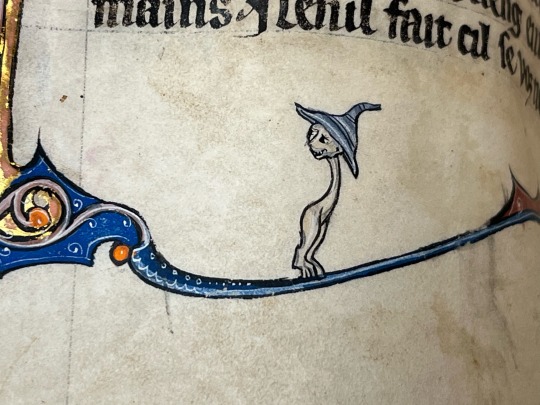

Weird Medieval Marginalia

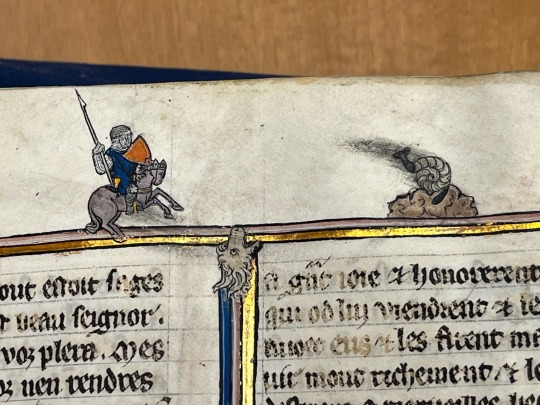

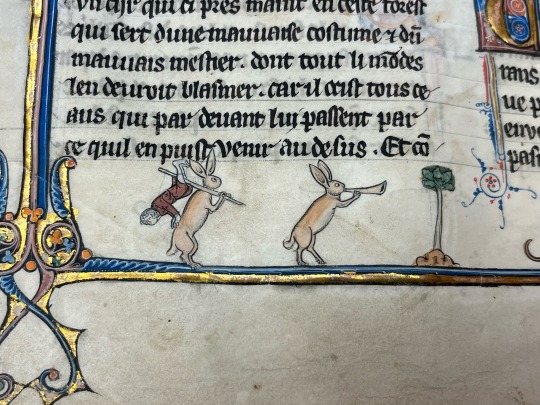

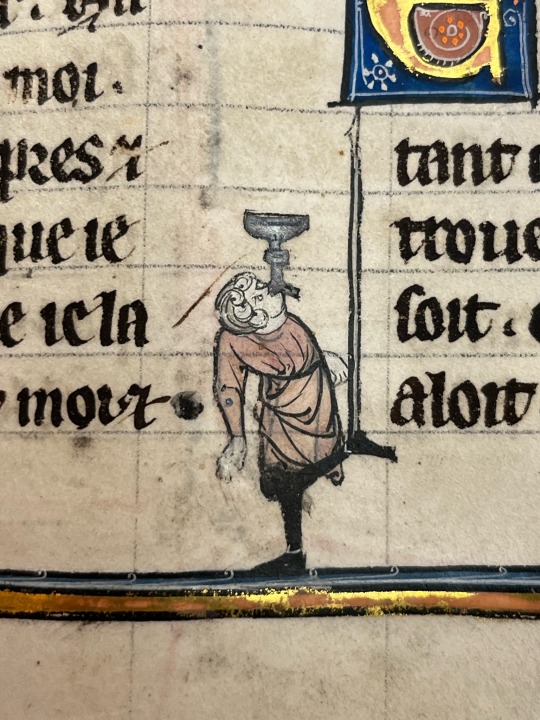

So I got to see an epically cool manuscript of Arthurian romance (Beinecke MS 229), written in French sometime in the thirteenth or fourteenth century. It contains many fully illuminated illustrations, but the most interesting thing about it turned out to be the marginalia.

All the big images were the same kinds of scenes of knights fighting, people going into or out of buildings, people lying in bed, occasionally people on boats or talking, etc. After a while they just felt repetitive. But there are these little cartoons in the margins, and they are WILD:

I mean I don’t even know what’s going on here.

Apparently knights fighting snails appear in a lot of manuscripts. We have no idea what they mean. Might be the medieval version of a meme.

What even is that gray thing?

Knight riding chicken.

Derpy horse.

A very weird-looking unicorn.

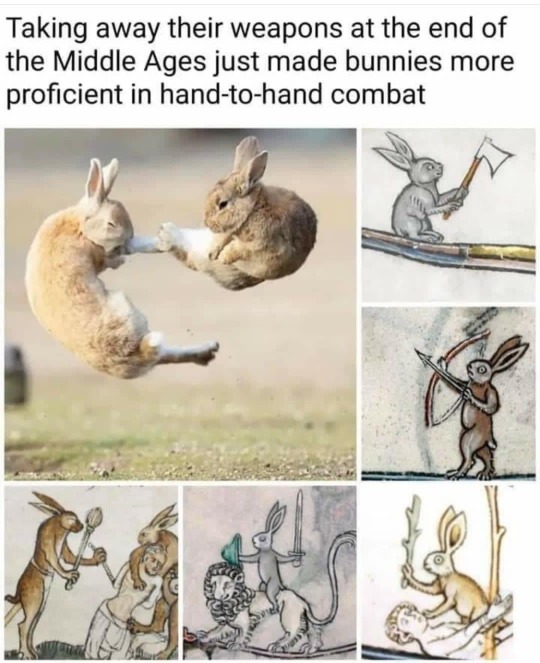

Rabbits hunting people. (RUN AWAY!!! RUN AWAY!!!)

Balancing act.

Baby Yoda in the corner there.

WHAT

There’s plenty more, but that’s as much as I can fit into one post. And this is all one manuscript!

129 notes

·

View notes

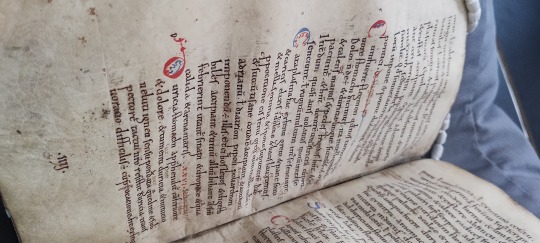

Text

This angle lets you see how the lines and margins were scored into the manuscript. Sometimes you see them marked out in plummet (lead, looks like they're drawn in pencil), but more often they're like this.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

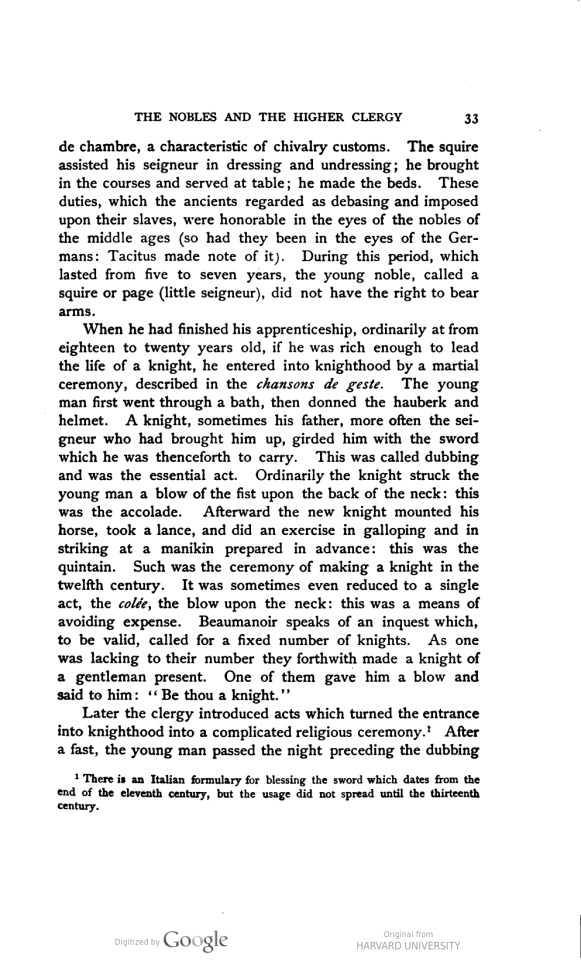

The Page/Becoming a Knight

Seignobos, Charles, 1854-1942, and Earle Wilbur Dow. The Feudal Régime.New York: H. Holt and company, 19041902.

6 notes

·

View notes

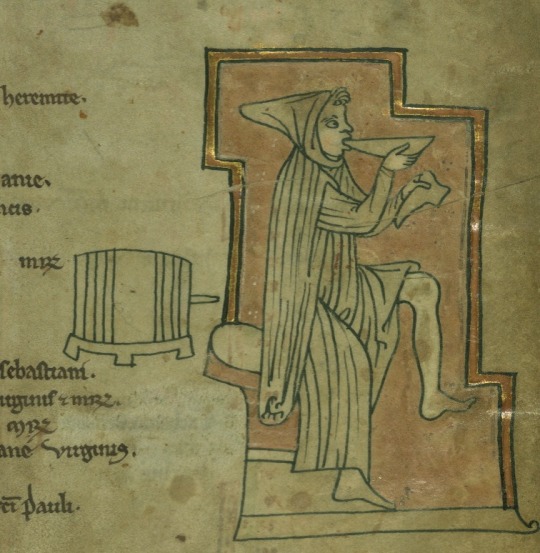

Text

A seated man drinking from a bowl with on hand and holding his shoe in the other

Touke Psalter W.36 f.3r Walters Art Museum

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

"a gyft of God that he hath geven us to excell all other nacions."

-Hugh Latimer on archery, 1549

Our friend the donkey (?) excels in the bottom margin of f. 200v, Ms. Codex 724, a 13th century Bible #drollerydonnerstag

🔗:

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIL richard the lionheart’s sexuality is apparently up for debate

via wikipedia.com

#was watching a lecture on the third crusade and this came up#richard the lionheart#middle ages#medieval#third crusade

0 notes

Text

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

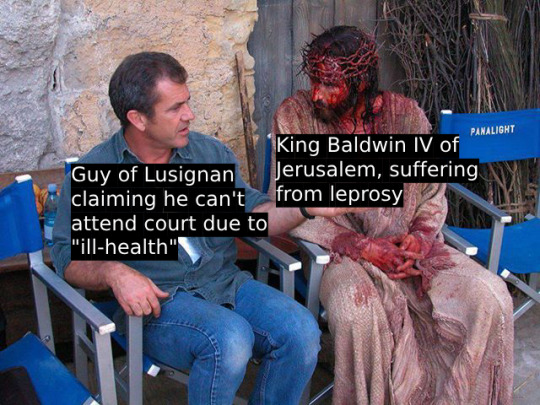

“Every Italian noble in the medieval commune era” - ENGLISH SUBTITLES

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

Little boy blue, come blow your horn!

A half-man, half-wolf, half... something toots his own horn in the bottom margin of f. 191r, Ms. Codex 724, a 13th century Bible #drollerydonnerstag

🔗:

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part of the reason that we don't tend to think of medieval women as workers is that the major expectation for them was that they would be wives and, crucially, mothers. A young woman, no matter her place in society, spent much of her time preparing for her eventual role as wife and mother in the household of her husband's family. Her parents wanted to ensure that they brought up their daughter in such a way that she would not "be a sore vexation to her bridegroom," as the Church father and theologian John of Chrysostom (347-407) put it. So when a young unmarried woman did receive, say, an education, it was largely tied to investing in her theoretical value as a bride. Well-educated women made for good wives since they could later educate their own children, as we will see. They would also be expected to run their own households, a job that involved fiscal acumen, and in the case of larger households, to manage staff. When a medieval girl was educated, it wasn't necessarily an altruistic activity to better her for her own good. It was a calculated marketing strategy and a means of marking her as an excellent potential mother.

The focus on motherhood and the getting of heirs existed for a number of reasons. As discussed in Chapter 3, for the rich, it was a way of ensuring that the property that a family had amassed would be passed down to a younger generation and their interests would be protected. Poor families needed children not necessarily to safeguard property but to have help on it. In an agricultural society, extra hands to help on the farm were in demand, especially when they didn't have to be paid wages. But regardless of whether you wanted kids to carry on your legacy or to help on the farm, you had to contend with one significant barrier: infant mortality. Children died at an incredibly high rate, not only in the medieval period but up until the twentieth century. At the very lowest, somewhere between 20 and 30 percent of all medieval children under seven died, though some put the mark as high as 50 percent. As a result, families required many more births of children than we are accustomed to in order to ensure viable heirs.

Producing all the heirs that their male relatives demanded put women's lives in real danger, but this danger was an accepted part of their position and calling as wives. The Hali Meidhad or Letter on Virginity, which was written in the English Midlands, acknowledged the pain, danger, and worry of mothers, stating that "in carrying [a child] there is heaviness and constant discomfort; in giving birth to it, the cruelest of all pains, and sometimes death; in bringing it up many weary hours. . . . By God, woman, . . . you should avoid this act above all things, for the integrity of your flesh, for the sake of your body, and for your physical health." The danger and pain—the real labor of childbirth and child rearing—were thus not lost of medieval commentators. This was the job that medieval women were expected to carry out, and it sucked.

Beyond childbirth and -rearing, the position of wife in and or itself implied work. According to Jerome, "Men marry, indeed, so as to get a manager for the house, to solace weariness, to banish solitude." The Letter on Virginity likewise directly challenges the idea that women benefit from subsuming themselves into marriage and motherhood. When a submissive would-be wife states that men's strength is needed for help with work and to secure adequate food, and that wealth is the result of marriage and several healthy children, the Letter asserts that such a picture of marriage deliberately misleads women, and that any advantages that they experience from marriage and motherhood come at too high a personal cost. Marriage, the Letter insists, is not a way of forming a team and enjoying a family but is "servitude to a man." Sugarcoat it one might, but marriage was not a romantic partnership but a contract, in which women signed themselves up for a life of grinding maternal labor as well as work alongside their husbands, for which they would not be acknowledged in historical records.

Medieval women appear as parts of households, or “wives of” named men in historical records. But wives were expected to take on the role of helpmeet and coworker alongside their husbands. Even those who heeded the warnings of the Church and turned from a life of motherhood toward God would find themselves working away inside nunneries. Similarly, single laywomen had to work to get by, and society marked out positions specifically for women who, for whatever reason, were not attached to a household. All these women are worth seeing as workers.

-Eleanor Janega, The Once and Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today (Nov. 11th) is Martinmas, the feast of St Martin of Tours, an important festival in medieval Europe on the very cusp of winter.

A 4th century Pannonian (present day Hungary) soldier, Martin's conversion to Christianity led him to give up his life in the Roman army. As Bishop of Tours he founded the famous abbey of Marmoutiers. Well known for his charity, here St. Martin is depicted cutting his cloak in half to share with a beggar.

Today he is venerated in the church as the patron saint of the poor, soldiers and conscientious objectors.

(Source: BnF NAF 16251: Images de la vie du Christ et des saints. 13th century (c. 1280-1290); f.89r)

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manuscript Monday comes to you with a nearly complete fifteenth-century Book of Hours from the Convent of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. This manuscript has two sections, the second having been added to the first within a generation of the book's manufacture. The first section of the manuscript (fols. 1-270) contains a standard Italian Dominican Book of Hours with a kalendar, Hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Office of the Dead, Penitential psalms, and Short Hours of the Cross. Exceptionally, unusual, however, are the contents of section two, which opens with a rare Office of the Glorious Virgin, followed by two Marian litanies. Such litanies multiplied in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and these follow the standard pattern of calling on the Virgin by her attributes, as a mother, brides, spouse, intercessor, etc. Learn more about this manuscript at the link below:

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 264 f.3r

Some nuns and monks playing shoulder wars

#i’m betting on the folks on the left#look at that expression!!!#medieval marginalia#medieval manuscripts#illuminated manuscript#middle ages#medieval

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

British Library Add MS 42130 f.43v

A woman throwing up a creature

#she should probably get that checked out#luttrell psalter#medieval marginalia#medieval manuscripts#illuminated manuscript#middle ages#medieval

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was recently commissioned by @/weirdmedieval on twitter to design some stickers for her shop, which was an absolute dream commission job to get! I’m really happy with how these came out, and they’re now available to buy!

You can get them from her big cartel, along with some sick pins, which is here!

185 notes

·

View notes