Text

Look, Rand was wrong about many things but she went off with the hedonism.

“The best aspect of Christmas is the aspect usually decried by the mystics: the fact that Christmas has been commercialized. The gift-buying . . . stimulates an enormous outpouring of ingenuity in the creation of products devoted to a single purpose: to give men pleasure. And the street decorations put up by department stores and other institutions — the Christmas trees, the winking lights, the glittering colors —provide the city with a spectacular display, which only ‘commercial greed’ could afford to give us. One would have to be terribly depressed to resist the wonderful gaiety of that spectacle.” - Ayn Rand, The Objectivist Calendar, December 1976

lol

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlas Shrugged Read-Through: PP 14-20

Our first introduction to the primary antagonist of Atlas Shrugged, Jim Taggart, is with him sitting at his desk saying "Don't bother me, don't bother me, don't bother me."

The unpleasant task that Eddie Willers has been facing is coming into Jim's office to tell him that a delivery of steel that has been delayed multiple times will be delayed again. Jim ordered the steel from his friend, Orren Boyle, who runs Associated Steel. Jim insists to Eddie that he won't hear of ordering the metal from the competing company, Rearden Steel, run by Hank Rearden. Taggart Transcontinental needs the steel because their Rio Norte line is too damaged to keep safely running trains on, and they are being outcompeted in the region by a small, local railroad called the Phoenix-Durango. Eddie is telling Jim to make a decision because the regional line supports the oil operation of Ellis Wyatt.

All of these are important characters and business that will come up a lot but they're not the real focus of this scene. The real focus of this scene is making Jim Taggart look like a big throbbing asshole, which is how you're supposed to think of him.

Here are a few of his lines from this brief scene:

"Who's thinking of giving up the Rio Norte Line?" he asked. "There's never been any question of giving it up. I resent your saying it. I resent it very much."

"Orren is my friend." He heard no answer. "I resent your attitude. Orren Boyle will deliver that rail just as soon as it's humanly possible. So long as he can't deliver it, nobody can blame us."

"Ellis Wyatt is a greedy bastard who's after nothing but money," said James Taggart. "It seems to me that there are more important things in life than making money."

"I think he's a destructive, unscrupulous ruffian. I think he's an irresponsible upstart who's been grossly overrated." It was astonishing to hear a sudden emotion in James Taggart's lifeless voice. "I'm not so sure that his oil fields are such a beneficial achievement. It seems to me that he's dislocated the economy of the whole country. Nobody expected Colorado to become an industrial state. How can we have any security or plan anything if everything changes all the time? [...] Yes, I know, I know, he's making money. But that is not the standard, it seems to me, by which one gauges a man's value to society. And as for his oil, he'd come crawling to us. and he'd wait his turn along with all the other shippers, and he wouldn't demand more than his fair share of transportation—if it weren't for the Phoenix-Durango. We can't help it if we're up against destructive competition of that kind. Nobody can blame us."

Jim Taggart is aggrieved. He is whiny, he doesn't accept responsibility for his actions, he resents people who are more active than he is (at least if they make demands on his time or cost him business by shifting their purchases to his competitors).

Jim is not written well, but the way that he is poorly written is interesting. Rand's big bad guy is an industrialist who doesn't take responsibility for his actions and who wants other people to do all of the hard work.

I'm going to get right to the big reveal in the middle of the book: Jim and the Moochers force through a law that means that nobody can compete with them. Other railroads shut down, new innovative companies have to give their capital to older businesses.

On the one hand, I think there's something clever that Rand is doing here. Jim and the Moochers use what is essentially "weaponized wokeness" (mealy-mouthed speeches about collectivism) to place themselves at the head of state-backed monopolies. They're not evil just because they're whiny and don't take responsibility, they're evil because they can use the power of the state to crush competitors, which also allows them to exploit workers and consumers.

On the other hand: I can't tell if Rand is being stupid or malicious in attributing the motivations for these actions to a collectivist impulse.

She clearly, obviously, deeply hated collectivism. But when each of her characters are revealed down to the nastiest, darkest parts of themselves it's revealed that their collectivist talk was meant to cover up personal greed. So I can't tell: stupid or malicious? Is she being stupid, and genuinely doesn't believe that anyone who talks about or works toward communal goods and shared resources actually wants those things? Or is she being malicious and suggesting that all people who claim to want to do things for the benefit of everyone are actually greedy and are trying to burn down the rest of the world so that they can stand on a slightly nicer bit of the ashes?

I haven't read much of Rand's non-fiction, or watched too many interviews with her, but I know that at one point she discussed the evils of altruism by saying that the Nazis were motivated by altruism. That seems like it's pulling a pretty bullshit rhetorical trick and defining "nationalism" as "altruism." And that's what she does with the evil characters in her books - makes them do terrible things while saying that they're doing so for the good of mankind when everybody knows the score. It's a bullshit rhetorical trick.

And this is how we're introduced to Jim Taggart. He's a wealthy industrialist who is whining to his sister's assistant that he can't be blamed that his friend is late with a delivery of steel. And I think Jim Taggart is a pretty good example of Rand being more malicious than stupid. We're going to learn a lot about his motivations and desires throughout the book and they come together to make a laboriously crafted strawman of an evil capitalist.

Anyway. Eddie walks out of their meeting after Jim insults his own sister; Eddie at that point finds an old clerk repairing a typewriter (one that has been repaired before and is made of inferior materials - planned obsolescence; a subject that I will have to yell about somewhere else) and asking Eddie if he knows where anyone can get woolen undershirts. Jim's office has been a break from the most visceral reminders of the bleak, slow-motion collapse of the economy that Eddie is confronted with as soon as he's out of the room again, and he is once again bothered by the question "Who is John Galt?" - the question that opened the novel in the mouth of a bum - as the introductory scene of the novel ends.

120 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi. I started following you recently because I also like Rand's writing but not her philosophies, and I would like to see the read-through, and don't mind if it's slow.

Of course, since I followed A New Blog, Tumblr's algorithm needs to push related blogs at me.

I don't think Tumblr understands what atlas-plugged actually is.

Ah! That is because these are both my blogs!

My main is @ms-demeanor and I have approximately 50 sideblogs, so tumblr's algorithm is correct that these are related in some way, but incorrect about what subject matter connects them.

Also, damn, I need to start lifting again.

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is a dead horse that I'm going to be beating *A LOT* on this blog, but Rand was so clearly so interested in writing consensual nonconsent, total power exchange, and cuckquean scenes between impossibly beautiful, emotionally stunted people that I believe that if she had found a way to survive off of writing that specific type of smut and nothing else the world would be a much better place.

Ayn Rand's characters are stilted and unnatural at nearly all times unless they are engaged in some bizarre psychosexual fuckery, in which case the wooden puppets she's been beating you over the head with become playful and dynamic and full of longing and denial.

There's a scene late at night when Dagny is overwhelmed trying to finish the John Galt Line in which she puts her head down on her desk and lets herself feel the weight of all her longing for someone who is an equal to help her share the load - that scene reads as very contrived, the desire it expresses comes off as artificial, and the story moves on to the next scene with no satisfaction.

Compare that with Dagny's last night in Galt's Gulch, when she and John are in separate rooms, wanting each other but denying their pleasure as part of an intricate ritual of grappling with power and belonging; the scene puts all of the tension and desire into the sound of a footstep and the click of a cigarette lighter and in a way that feels believable and cathartic even as it thwarts the desires of the two characters because the eroticism is in their shared denial.

The parts of Rand's books that deal with sex are always the parts that seem the least practiced and most sincere, even if that's Dominique getting rawed by a man she hates in order to shame Roark for not doing enough to deserve her. Even when her villains fuck it gives more insight into their characters than nearly any other scenes they're in. Considering how many interminable bitchy party scenes she writes to show off how horrible most of her non-main female characters are, this is shocking.

I haven’t read Atlas since 2005, so I’m stoked to passively ingest snarky commentary.

It always seemed to me that the people around me who were most in love with this book often particularly love the idea that other people should love them regardless of how they treat other people. Like, being a dick, or just not having very good social skills, shouldn’t tarnish the adulation due to Smart People TM, (my super cringe teenage self included) who should run the world.

I’m super curious if this matches your observations.

So I'll tell you about the two people who I most vividly remember loved Atlas Shrugged when I was working at the coffee shop and they saw me reading it.

One person was a young latina woman who had worked her way through college and law school and who had passed the bar a year before and was working overwhelming hours at a law firm where she was getting significant raises on a regular basis. The job was difficult, and she always seemed on the verge of burnout, but she was very firmly entrenched in the idea that hard work paid off and liked the book because it was about people who were brilliant and rich and worked hard anyway and they came out on top in the end.

The other person who loved it was a middle-aged man who worked taking bets at the racetrack and who was a literal, actual VOCAL member of the John Birch Society. He was notable for two habits: he never tipped, and while he never bought his own pack of cigarettes he would also never, ever allow you to *give* him cigarettes, so he would 'bum' smokes from me and pay me a quarter each (this was when a pack cost about five dollars, so that was just about what a cigarette cost). He liked the book because he thought the world was full of moochers (he's the only person I've ever spoken to who would regularly refer to people that way in conversation) and the book was a story where the moochers got what was coming to them for once.

These were VERY different people who took pretty different messages from the book for very different reasons.

I think the central fantasy of Atlas Shrugged is that it is full of characters who are loved and valued for the thing that they most value about themselves. It is a book that is not just about a meritocracy, it is about a Meritopia. It is about people who get the things they want because they are the best at what they do. This is CENTRAL to the story.

The reason I used the term "Matryoshka of Cuckoldry" to describe the relationships is because of this meritocratic point of view. Eddie loves Dagny but is not jealous of the fact that she wants Francisco because Francisco is a better man than Eddie. Francisco wants Dagny, but understands her passion for Hank because Hank is a good man who is currently part of her world in a way that Francisco can't be. Hank *sends her a letter* letting her know that he's okay with her leaving him for Galt because he meets Galt and understands why Dagny can't love Hank anymore once she has met the pinnacle of humanity. Then both of her exes help her rescue her current lover because he is a better man than them.

The Fountainhead has a much more literal cucking thing going on with Dominique marrying and fucking two men who she thinks are much worse than Roark, sullying herself with their lust until Roark chooses to stop sullying himself by operating in a world that doesn't value him the way that she does.

What is the same in both of these novels, and what I think you are pointing at in your ask, is that the horrible characters are loved for the things that they love about themselves, and all of their unloveable traits don't matter.

That is the fantasy that people are getting from Atlas Shrugged, and that's why you might find some real assholes out there "Looking for their Dagny/Galt" (a literal phrase I have seen on Libertarian dating sites!).

And you know what, I can be sympathetic to that.

I was raised to value intellect over everything else. Academic achievement, high test scores, acceptance to a good college, and being smarter and more knowledgeable than all my peers was what I was taught was more important than being kind, or being polite, or making friends, or taking care of my mental health.

That meant that I really, really, really wanted people to love me for how smart I was.

And, well. The thing about that is, I ended up loving and being loved by people who didn't care if I was cruel or selfish, and who didn't mind being cruel or selfish to me.

I'm still kind of an asshole. And since I started dating my spouse within three months of when I first read Atlas Shrugged, it's not a surprise that he doesn't care much if I'm nice to people and is, himself, kind of an asshole (though, notably, he is not an asshole with me and part of me getting better has been both of us learning to draw boundaries on how we are willing to be treated by one another).

But oh my god, I'm never an asshole like I am when I'm around my dad. I'm never as much of a snob as I am when he brings it out in me. I'm never as mean as I am when I'm talking to him. And I've never stopped hearing from my dad that I'm too smart to be doing the job that I'm doing, that I'm too smart to be going back to school for a different degree, that I should be getting a PhD and focusing on one field because that's what I'm best at and the rest of the world should recognize it. I know that's what my dad loves about me more than anything else he loves about me. He thinks I'm smarter than him, and he thinks that's awesome, and he thinks that everything I do that is not about harnessing raw intelligence into an academic career is a waste of my mind and time.

So there is a part of me that deeply identifies with these characters whose best trait is their efficiency, who never bother to be nice because it would slow them down in the process of being perfect. I desperately understand the fantasy of someone saying "you are the best in the world at this one specific thing and I find that so sexy that I don't care about your lack of work/life balance, offputting personality, and total lack of skills unrelated to your area of interest."

(Of note: another part of this fantasy in the novel is that skill in one area translates to skill in others. There's a philosopher who is also an incredible short order cook; there's a banker who is also a brilliant tobacco grower; there's a railroad executive who is also an expert maid because Ayn Rand is so fucking kinky she doesn't know what to do with herself)

That's just, you know, a shitty way to live and means you treat people like crap and sometimes that takes a little while to understand that and figure out how to be less of an asshole.

Also: part of the fantasy is that you actually ARE good enough at any one thing that that's what someone will love you for. Most of us aren't! And that's a good thing actually, because people should love you for more than one aspect of yourself!

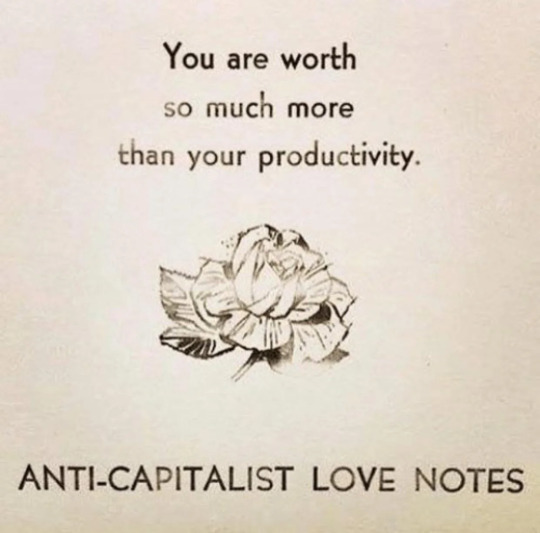

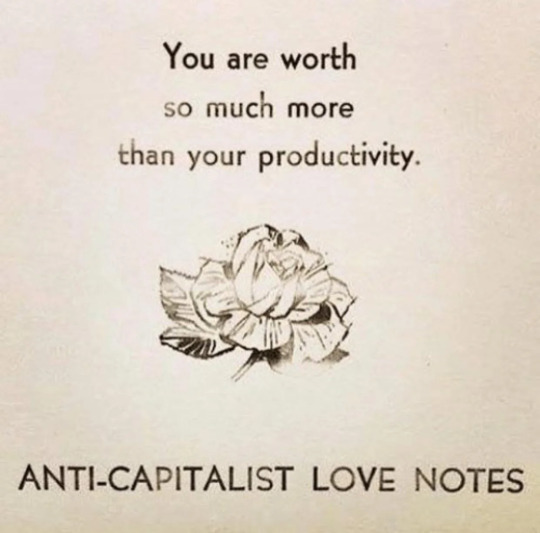

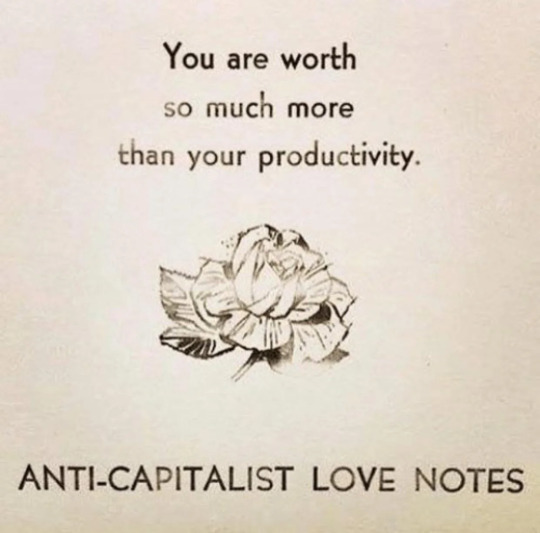

I've said it before and I'll say it again: one of the most important things that I've ever come across for my mental health is this image:

[ETA: the image is a print by Nicole Manganelli of Radical Emprints and you can get one here.]

I saw it on Tumblr some time in 2013 or thereabouts and instantly recoiled from it. I was angry about it. It was *WRONG.* At that point, in my mind, ALL that you are were worth was your productivity. That was literally all that you had to offer to the world, and literally all that people could love you for.

That's the Atlas Shrugged mindset. That's what the people who are fans of the book are carrying around in their heads. That's why they think it doesn't matter if they're an asshole, so long as they're rich enough, or work hard enough, or are the best at enough things, or have enough to make up for the fact that they aren't anything outside of their productivity.

But the picture wasn't wrong, I was wrong.

Anyway, I've done a lot of therapy about it and that's the best answer I've come up with.

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

When I was applying to colleges and scholarships, one of the most well-publicized scholarship competitions was the Ayn Rand Foundation's essay competitions. "Write a short essay about a 100-page book?" I thought. "What an easy scholarship application!" And that's how I read Anthem for the first and only time and let me tell you when you weren't raised by libertarians that stuff makes SIGNIFICANTLY less sense. Looking forward to learning about it from someone who understands the philosophy.

Anthem was the first Rand I ever read and honestly I loved it. It was assigned as a reading for my freshman lit class when I was 14 and it slotted in neatly beside a lot of the other dystopic fiction that gets handed to young teens. It was more mature than The Giver, longer than "Harrison Burgeron," and invited the reader into the characters' headspaces in a way that I didn't really get from Fahrenheit 451.

Anthem and "Harrison Burgeron" were part of a unit for that class and looking back, I can't help but wonder if that unit was specifically constructed to get freshman honors English students to start thinking about intellectual elitism.

Again, look, I was kind of a little asshole. I was a kid without a hell of a lot of social skills who was both learning disabled and advanced; I had tested out of several grades (which, thankfully, the district would not advance me through) and was extremely violently bullied for years by the students who had been told "Why can't you be like Alli?" by our teachers (and, not that there's an excuse for bullying, I was a shit about the fact that I was a better student than my classmates)* so "Harrison Burgeron" *resonated.* The idea of an unshackled human as a threat to the society that wanted to drag everyone down to the lowest common denominator was like *catnip* to me. I transcribed that story in a journal by hand.

Then Anthem followed, and Anthem builds on those same themes. It is about a person whose strengths are suppressed by his society, who is punished for his individuality, who has had his choices taken away from him, and who breaks away from all of that to try to build a better world.

I think that Anthem actually makes a lot of sense to a lot of teenagers, and that's part of why the Ayn Rand Institute has a free books for teachers program and has run that scholarship contest for decades. They very much want as many edgy teens to get into Rand as early as possible. I know that if I hadn't read (and loved) Anthem so long that I probably wouldn't have been as interested in Atlas Shrugged as I was when I finally got around to it.

They do scholarships about The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged too. I've helped marxist friends write their papers for the ARI, which I think resulted in at least one scholarship.

(If you have the opportunity to take these people for their money, do it. Fuck them. I give 5:1 odds that you're a better writer and thinker than the majority of people submitting essays, so do it, go for it, take their money and use it to pay for a degree that is absolutely flooded with the kinds of critical theory that they would loathe.)

In another post I discussed the woundedness of Rand's ideology. You see this a lot with a lot of the right, actually - it manifests in the idea that you want a better world for everyone except for the people who hurt you.

This is very visible in Atlas Shrugged, which is half power fantasy, half revenge story. It is not enough that the heroes must win, but that their enemies must suffer.

The idea that those who have done you harm are beyond redemption, beyond saving, and could never have a place in your perfect world is a very adolescent idea and part of why I think Rand's work does resonate so much with edgy teens. Edgy teens often think of themselves as apart from and othered by society, and they don't want to meaningfully contribute to a society that injured them.

But you've got to grow up sometime. "I struggled and suffered, so the next person should struggle and suffer" or "you made me struggle and suffer, so I won't improve things for anyone if improving things might help you" is spiteful and petty, and something that makes sense for cynical teenagers but that is ridiculous and immature when you see adults pulling that shit.

So I understand the kids who went "cool dystopia!" and maybe internalized a story about chosen ones. I understand adults who found that appealing and read further and sat in that space for a while. What I don't understand is adults who make denying assistance to others a part of their worldview under the assumption that providing assistance to anyone is hampering individuals from reaching their full potential.

-

-

*In some ways I feel like I got set up for failure by a lot of adults. I switched districts in the 3rd grade, when I was already nearly a year younger than almost everyone in my class (I turned 8 two days before school started) and the district wouldn't allow me to advance to the 6th grade based on my testing (thank fuck) or put me in GATE classes (whatever) but whatever chance I had of being a "normal" kid got shattered when my 3rd grade teacher had me teach the rest of the class our multiplication tables and assigned me the job of doing half an hour of reading aloud to the class for a couple days each week while she caught up on grading. I was not the teacher's pet so much as I was the weird 8-year-old reading Moby Dick at recess and having trouble maintaining friendships because of emotional dysregulation. Being a smart kid with essentially no friends who was *horribly, violently bullied in ways that led to lasting injuries* probably wasn't the only reason that I liked Anthem but it was very much why I was drawn to chosen-one-under-attack-by-society-must-save-the-day narratives.

Anyway in case it wasn't clear I'm obviously still wrestling with a lot of this stuff and this blog is likely to be just as much trauma dumping as it is talking about Ayn Rand's Bad Book.

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've read the novel several dozen times and I find it genuinely compelling as fiction. I like many of the characters, I find the plot interesting, and I like much of the prose.

The novel is also quite sexual and the sexuality is unabashedly kinky (or unaware of its kinkiness), which I think is an under-discussed part of its appeal. The kink is good. It would be better if anyone acknowledged it, but I maintain that Rand could have been a wonderful writer of erotica.

One of the major things that people hate about the book is that it is about 1100 pages (560k words), and another thing they hate is that there is a literal seventy page monolog on the virtue of selfishness in the final third of the story. It can be very tedious and is very repetitive. Rand was extremely unsubtle and at times it is less like reading a novel and more like getting hit in the face repeatedly with a hammer made out of Rand's opinions.

It's a cringy book and cringe things happen in it! There's an extended narration about a factory failing because unions are literally communism, it goes on nonstop about how torturous regulations are for businesses, and the moral of the story is: rugged individualism good, collectivism bad.

I get why people like it. I like it! But it's not the kind of thing I'd ever recommend that anyone read and the central philosophy of the book is dogshit, which is why Randeroids are such a tire fire as a Fandom.

Also several of them are republican members of the house and senate. "My favorite book is Atlas Shrugged" is shorthand for "I would rather see people starve than put them on welfare because the threat of starvation is a good motivator to work" and that's why a lot of Republicans and right-wing trolls and media types name check it so often.

I haven’t read Atlas since 2005, so I’m stoked to passively ingest snarky commentary.

It always seemed to me that the people around me who were most in love with this book often particularly love the idea that other people should love them regardless of how they treat other people. Like, being a dick, or just not having very good social skills, shouldn’t tarnish the adulation due to Smart People TM, (my super cringe teenage self included) who should run the world.

I’m super curious if this matches your observations.

So I'll tell you about the two people who I most vividly remember loved Atlas Shrugged when I was working at the coffee shop and they saw me reading it.

One person was a young latina woman who had worked her way through college and law school and who had passed the bar a year before and was working overwhelming hours at a law firm where she was getting significant raises on a regular basis. The job was difficult, and she always seemed on the verge of burnout, but she was very firmly entrenched in the idea that hard work paid off and liked the book because it was about people who were brilliant and rich and worked hard anyway and they came out on top in the end.

The other person who loved it was a middle-aged man who worked taking bets at the racetrack and who was a literal, actual VOCAL member of the John Birch Society. He was notable for two habits: he never tipped, and while he never bought his own pack of cigarettes he would also never, ever allow you to *give* him cigarettes, so he would 'bum' smokes from me and pay me a quarter each (this was when a pack cost about five dollars, so that was just about what a cigarette cost). He liked the book because he thought the world was full of moochers (he's the only person I've ever spoken to who would regularly refer to people that way in conversation) and the book was a story where the moochers got what was coming to them for once.

These were VERY different people who took pretty different messages from the book for very different reasons.

I think the central fantasy of Atlas Shrugged is that it is full of characters who are loved and valued for the thing that they most value about themselves. It is a book that is not just about a meritocracy, it is about a Meritopia. It is about people who get the things they want because they are the best at what they do. This is CENTRAL to the story.

The reason I used the term "Matryoshka of Cuckoldry" to describe the relationships is because of this meritocratic point of view. Eddie loves Dagny but is not jealous of the fact that she wants Francisco because Francisco is a better man than Eddie. Francisco wants Dagny, but understands her passion for Hank because Hank is a good man who is currently part of her world in a way that Francisco can't be. Hank *sends her a letter* letting her know that he's okay with her leaving him for Galt because he meets Galt and understands why Dagny can't love Hank anymore once she has met the pinnacle of humanity. Then both of her exes help her rescue her current lover because he is a better man than them.

The Fountainhead has a much more literal cucking thing going on with Dominique marrying and fucking two men who she thinks are much worse than Roark, sullying herself with their lust until Roark chooses to stop sullying himself by operating in a world that doesn't value him the way that she does.

What is the same in both of these novels, and what I think you are pointing at in your ask, is that the horrible characters are loved for the things that they love about themselves, and all of their unloveable traits don't matter.

That is the fantasy that people are getting from Atlas Shrugged, and that's why you might find some real assholes out there "Looking for their Dagny/Galt" (a literal phrase I have seen on Libertarian dating sites!).

And you know what, I can be sympathetic to that.

I was raised to value intellect over everything else. Academic achievement, high test scores, acceptance to a good college, and being smarter and more knowledgeable than all my peers was what I was taught was more important than being kind, or being polite, or making friends, or taking care of my mental health.

That meant that I really, really, really wanted people to love me for how smart I was.

And, well. The thing about that is, I ended up loving and being loved by people who didn't care if I was cruel or selfish, and who didn't mind being cruel or selfish to me.

I'm still kind of an asshole. And since I started dating my spouse within three months of when I first read Atlas Shrugged, it's not a surprise that he doesn't care much if I'm nice to people and is, himself, kind of an asshole (though, notably, he is not an asshole with me and part of me getting better has been both of us learning to draw boundaries on how we are willing to be treated by one another).

But oh my god, I'm never an asshole like I am when I'm around my dad. I'm never as much of a snob as I am when he brings it out in me. I'm never as mean as I am when I'm talking to him. And I've never stopped hearing from my dad that I'm too smart to be doing the job that I'm doing, that I'm too smart to be going back to school for a different degree, that I should be getting a PhD and focusing on one field because that's what I'm best at and the rest of the world should recognize it. I know that's what my dad loves about me more than anything else he loves about me. He thinks I'm smarter than him, and he thinks that's awesome, and he thinks that everything I do that is not about harnessing raw intelligence into an academic career is a waste of my mind and time.

So there is a part of me that deeply identifies with these characters whose best trait is their efficiency, who never bother to be nice because it would slow them down in the process of being perfect. I desperately understand the fantasy of someone saying "you are the best in the world at this one specific thing and I find that so sexy that I don't care about your lack of work/life balance, offputting personality, and total lack of skills unrelated to your area of interest."

(Of note: another part of this fantasy in the novel is that skill in one area translates to skill in others. There's a philosopher who is also an incredible short order cook; there's a banker who is also a brilliant tobacco grower; there's a railroad executive who is also an expert maid because Ayn Rand is so fucking kinky she doesn't know what to do with herself)

That's just, you know, a shitty way to live and means you treat people like crap and sometimes that takes a little while to understand that and figure out how to be less of an asshole.

Also: part of the fantasy is that you actually ARE good enough at any one thing that that's what someone will love you for. Most of us aren't! And that's a good thing actually, because people should love you for more than one aspect of yourself!

I've said it before and I'll say it again: one of the most important things that I've ever come across for my mental health is this image:

[ETA: the image is a print by Nicole Manganelli of Radical Emprints and you can get one here.]

I saw it on Tumblr some time in 2013 or thereabouts and instantly recoiled from it. I was angry about it. It was *WRONG.* At that point, in my mind, ALL that you are were worth was your productivity. That was literally all that you had to offer to the world, and literally all that people could love you for.

That's the Atlas Shrugged mindset. That's what the people who are fans of the book are carrying around in their heads. That's why they think it doesn't matter if they're an asshole, so long as they're rich enough, or work hard enough, or are the best at enough things, or have enough to make up for the fact that they aren't anything outside of their productivity.

But the picture wasn't wrong, I was wrong.

Anyway, I've done a lot of therapy about it and that's the best answer I've come up with.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

*screams*

THANK YOU TO MY STATE-FUNDED, LOW-COST COMMUNITY COLLEGE, I LOVE YOU AND I LOVE THE FACT THAT MY ENROLLMENT MEANS THAT I HAVE FREE ACCESS TO THE ENTIRE BACK CATALOGUE OF THE JOURNAL OF AYN RAND STUDIES.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

!!! I forgot that I already had a tag for the sexuality in Atlas Shrugged, so if you want to specifically look for (or block!) discussions of sex in Atlas Shrugged the tags to look out for (so far) are "matryoshka of cuckoldry" and "Dagny Taggart's Himbo Harem."

185 notes

·

View notes

Note

I haven’t read Atlas since 2005, so I’m stoked to passively ingest snarky commentary.

It always seemed to me that the people around me who were most in love with this book often particularly love the idea that other people should love them regardless of how they treat other people. Like, being a dick, or just not having very good social skills, shouldn’t tarnish the adulation due to Smart People TM, (my super cringe teenage self included) who should run the world.

I’m super curious if this matches your observations.

So I'll tell you about the two people who I most vividly remember loved Atlas Shrugged when I was working at the coffee shop and they saw me reading it.

One person was a young latina woman who had worked her way through college and law school and who had passed the bar a year before and was working overwhelming hours at a law firm where she was getting significant raises on a regular basis. The job was difficult, and she always seemed on the verge of burnout, but she was very firmly entrenched in the idea that hard work paid off and liked the book because it was about people who were brilliant and rich and worked hard anyway and they came out on top in the end.

The other person who loved it was a middle-aged man who worked taking bets at the racetrack and who was a literal, actual VOCAL member of the John Birch Society. He was notable for two habits: he never tipped, and while he never bought his own pack of cigarettes he would also never, ever allow you to *give* him cigarettes, so he would 'bum' smokes from me and pay me a quarter each (this was when a pack cost about five dollars, so that was just about what a cigarette cost). He liked the book because he thought the world was full of moochers (he's the only person I've ever spoken to who would regularly refer to people that way in conversation) and the book was a story where the moochers got what was coming to them for once.

These were VERY different people who took pretty different messages from the book for very different reasons.

I think the central fantasy of Atlas Shrugged is that it is full of characters who are loved and valued for the thing that they most value about themselves. It is a book that is not just about a meritocracy, it is about a Meritopia. It is about people who get the things they want because they are the best at what they do. This is CENTRAL to the story.

The reason I used the term "Matryoshka of Cuckoldry" to describe the relationships is because of this meritocratic point of view. Eddie loves Dagny but is not jealous of the fact that she wants Francisco because Francisco is a better man than Eddie. Francisco wants Dagny, but understands her passion for Hank because Hank is a good man who is currently part of her world in a way that Francisco can't be. Hank *sends her a letter* letting her know that he's okay with her leaving him for Galt because he meets Galt and understands why Dagny can't love Hank anymore once she has met the pinnacle of humanity. Then both of her exes help her rescue her current lover because he is a better man than them.

The Fountainhead has a much more literal cucking thing going on with Dominique marrying and fucking two men who she thinks are much worse than Roark, sullying herself with their lust until Roark chooses to stop sullying himself by operating in a world that doesn't value him the way that she does.

What is the same in both of these novels, and what I think you are pointing at in your ask, is that the horrible characters are loved for the things that they love about themselves, and all of their unloveable traits don't matter.

That is the fantasy that people are getting from Atlas Shrugged, and that's why you might find some real assholes out there "Looking for their Dagny/Galt" (a literal phrase I have seen on Libertarian dating sites!).

And you know what, I can be sympathetic to that.

I was raised to value intellect over everything else. Academic achievement, high test scores, acceptance to a good college, and being smarter and more knowledgeable than all my peers was what I was taught was more important than being kind, or being polite, or making friends, or taking care of my mental health.

That meant that I really, really, really wanted people to love me for how smart I was.

And, well. The thing about that is, I ended up loving and being loved by people who didn't care if I was cruel or selfish, and who didn't mind being cruel or selfish to me.

I'm still kind of an asshole. And since I started dating my spouse within three months of when I first read Atlas Shrugged, it's not a surprise that he doesn't care much if I'm nice to people and is, himself, kind of an asshole (though, notably, he is not an asshole with me and part of me getting better has been both of us learning to draw boundaries on how we are willing to be treated by one another).

But oh my god, I'm never an asshole like I am when I'm around my dad. I'm never as much of a snob as I am when he brings it out in me. I'm never as mean as I am when I'm talking to him. And I've never stopped hearing from my dad that I'm too smart to be doing the job that I'm doing, that I'm too smart to be going back to school for a different degree, that I should be getting a PhD and focusing on one field because that's what I'm best at and the rest of the world should recognize it. I know that's what my dad loves about me more than anything else he loves about me. He thinks I'm smarter than him, and he thinks that's awesome, and he thinks that everything I do that is not about harnessing raw intelligence into an academic career is a waste of my mind and time.

So there is a part of me that deeply identifies with these characters whose best trait is their efficiency, who never bother to be nice because it would slow them down in the process of being perfect. I desperately understand the fantasy of someone saying "you are the best in the world at this one specific thing and I find that so sexy that I don't care about your lack of work/life balance, offputting personality, and total lack of skills unrelated to your area of interest."

(Of note: another part of this fantasy in the novel is that skill in one area translates to skill in others. There's a philosopher who is also an incredible short order cook; there's a banker who is also a brilliant tobacco grower; there's a railroad executive who is also an expert maid because Ayn Rand is so fucking kinky she doesn't know what to do with herself)

That's just, you know, a shitty way to live and means you treat people like crap and sometimes that takes a little while to understand that and figure out how to be less of an asshole.

Also: part of the fantasy is that you actually ARE good enough at any one thing that that's what someone will love you for. Most of us aren't! And that's a good thing actually, because people should love you for more than one aspect of yourself!

I've said it before and I'll say it again: one of the most important things that I've ever come across for my mental health is this image:

[ETA: the image is a print by Nicole Manganelli of Radical Emprints and you can get one here.]

I saw it on Tumblr some time in 2013 or thereabouts and instantly recoiled from it. I was angry about it. It was *WRONG.* At that point, in my mind, ALL that you are were worth was your productivity. That was literally all that you had to offer to the world, and literally all that people could love you for.

That's the Atlas Shrugged mindset. That's what the people who are fans of the book are carrying around in their heads. That's why they think it doesn't matter if they're an asshole, so long as they're rich enough, or work hard enough, or are the best at enough things, or have enough to make up for the fact that they aren't anything outside of their productivity.

But the picture wasn't wrong, I was wrong.

Anyway, I've done a lot of therapy about it and that's the best answer I've come up with.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlas Shrugged Read-Through: PP 11-14

As far as starting your novel in media res goes, it takes pretty big balls to make your opening line the motif that will haunt the rest of the book. The story starts out right away with "Who is John Galt?" and clumsily tries to catch up to it.

Our introductory POV character (the story is told mostly in first-person limited with occasional dips into third person omniscient) is Eddie Willers, who is undoubtedly one of the more likable characters in the book. Eddie is 32, straightens his spine with "self-conscious discipline" and we meet him as he's giving a dime to a panhandler on the street.

I like Eddie for that. Eddie is unnerved by the man asking him for change, and is unnerved at the constant refrain of the city that seems to be cadging dimes out of the pockets of the well-to-do, but Eddie doesn't pause. He is uncomfortable, but he gets the dime out of his pocket anyway.

Eddie is walking the streets of New York at sunset, trying to figure out what is causing the anxiety that's preying on his mind. He eventually settles into the realization that twilight is making him anxious.

This is because, in the context of the novel, the industrial world is in its twilight.

And this is because Ayn Rand was the least subtle person on the planet.

Further evidence of Rand's earth-shaking unsubtlety is the giant calendar projected on the roof of a skyscraper that will become a way of marking Serious Happenings in the novel. The calendar also makes Eddie uneasy, and looking at it gnaws on him for a page or two until he realizes that the calendar has made him think of the phrase "your days are numbered."

As Eddie walks through the street we are taken on a tour of his anxieties; he is unnerved by the increased frequency of people asking for cash, disturbed by the coming darkness and the numbered days of the calendar, and the fading brightness of the city reminds him of a lightning-struck tree that he saw as a child, one that was already rotted from the inside by the time it was hit in a storm.

There's a paragraph here that I almost like for its language, and that I actually like because of what it says about Rand. The paragraph reads:

The clouds and shafts of skyscrapers against them were turning brown, like an old painting in oil, the color of a fading masterpiece. Long streaks of grime ran from under the pinnacles down the slender, soot-eaten walls. High on the side of a tower there was a crack in the shape of a motionless lightning, the length of ten stories. A jagged object cut the sky above the roofs; it was half a spire, still holding the glow of the sunset; the gold leaf had long since peeled off the other half. The glow was red and still, like the reflection of a fire: not an active fire, but a dying one which is too late to stop (12).

What I almost like about that paragraph is the way that it's written. When I say that I find Rand's prose compelling, this is part of what I mean. The image of a glass skyscraper with half its reflection gone dark because it was unmaintained after all the effort to build it is arresting.

What I actually like about that paragraph is that it's not quite a full page into the book and Rand is already telling you exactly how much credit she gives her readers. It is not enough for her to imply that the buildings are poorly maintained, or to later comment on the number of closed shops or the rusty mechanisms of the streetlights, she has to make sure that you understand that things are bad in Eddie Willers' world, and that the city looks like a dying fire.

Eddie continues his journey, passing a busy street in which only 20% of the shops are dark. He walks down the sidewalk and feels protective of displays of competence (bright vegetables on sale at a stall, an expertly steered bus) and advances toward a meeting that he doesn't want to have.

The text is very clear about what kind of man Eddie Willers is. He is a man who likes productivity, a man who unflinchingly faces unpleasant tasks with his head held high and the knowledge that his effort will be of use to the people (and one specific person) who rely on him. He is not a fighter, he is not a brilliant engineer or a great thinker: he is a man whose existence is "a quiet, scrupulous progression" (13).

In the next segment (Atlas Shrugged is divided into three books of ten chapters, or 30 chapters that average about 36 pages each; each segment is typically divided into several segments with differing points of view) we will learn that Eddie is the "Special Assistant to the Vice-President in Charge of Operation, and his main duty was to be her bodyguard against any waste of time" (25). Eddie isn't a man who gets things done, he is a man who clears the path for other people to get things done.

We are meant to appreciate Eddie, but I also think we're supposed to be contemptuous of his passivity. He is a little man living his life and (explicitly) trying to do what is right, and in Rand's writing that's not enough to make him admirable.

In the matryoshka of cuckoldry* that would be a love triangle in another novel, Eddie is the outermost doll.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Eddie is on his way to an unpleasant task: that unpleasant task is to tell the president of the company that he works for that they can't let a railroad line fail.

This is a novel about industrialists.

While it was written in the 50s it seems to have a kind of timelessness, or out-of-timeness to it. If it seems a little odd that the central conflict of a novel in the 50s would be about the failure of a railroad company, it is. The first recorded usage of "Jet Set" was in the late 40s to early 50s, and it seems, frankly, bizarre that a book published in 1957 would have trains this central to the story.

It is really, really difficult to over-emphasize how much trains matter to this book.

And, look, I get that transit is Super Fucking Important to how the world works - we have all recently experienced what supply chain interruptions can do to the world - but trains are more than transit in Atlas Shrugged. Taggart Transcontinental - the railroad that Eddie works for - is presented as a cultural symbol and a metaphor for freedom and UNIRONICALLY!!!!! an example of what determined individuals can do if unhampered by regulation.

So it doesn't read like a novel that is taking place in the 1950s, it reads like a novel that is taking place much earlier than that.

But: back to the actual text.

Eddie is determined in facing his terrible duty: speaking to his boss. Eddie walks through the Taggart Transcontinental Building, immediately comforted by its warm, productive atmosphere, and goes upstairs to talk to Jim Taggart, president of Taggart Transcontinental, who is the older brother of Dagny Taggart (the protagonist of the novel, and Eddie's direct supervisor).

Taggart's textual introduction is another example of Rand's writing actually being kind of okay:

"He looked like a man approaching fifty, who had crossed into age from adolescence, without the intermediate stage of youth" (14). That's good shit. It's evocative. It's followed by eighty words of description that undo all the wit of that zinger: "His posture had a limp, decentralized sloppiness, as if in defiance of his tall, slender body, a body with an elegance of line intended for the confident poise of an aristocrat, but transformed into the gawkiness of a lout. The flesh of his face was pale and soft. His eyes were pale and veiled, with a glance that moved slowly, never quite stopping, gliding off and past things in eternal resentment of their existence. He looked obstinate and drained. He was thirty-nine years old."

Everyone who has done even half a second of criticism Rand has noted that she is too wordy. It is practically a given. What people don't often discuss is that half of the words are good, they just get spoiled by the other half. Just like the dying fire example we looked at earlier, this description of Jim Taggart could be cutting, but she dulls her words by throwing too many of them at you. And that's not even getting into the weird body shit that will crop up again and again.

Or her obviousness.

Jim Taggart's sloppy posture is a misuse of his body that makes an aristocrat into a lout; Jim Taggart's misuse of his family's company makes him into a moocher instead of an industrialist. He is squandering his inherited gifts out of a sense of misplaced guilt over possession of those gifts; this is expressed in his physical person as well as in his business dealings.

Anyway, that's where I'm going to call it for today. We've met Eddie, we've seen the streets of New York, we're inside the Taggart Transcontinental building, and we've seen Jim but we aren't talking to him yet.

This chapter is called "The Theme" and that is apt because the themes are being laid out before we've even met or protagonist and before our antagonist has even opened his mouth.

There is one more thing I would like to highlight, though:

At one point in the chapter, Eddie remembers the answer he gave when asked what he would like to do when he grew up. His answer was "Whatever is right," and as he walks toward the Taggart Transcontinental building he reflects on this:

"He still thought it self-evident that one had to do what was right; he had never learned how people could want to do otherwise; he had learned only that they did. It still seemed simple and incomprehensible to him: simple that things should be right, and incomprehensible that they weren't. He knew that they weren't" (14).

Eddie knows that something is wrong in the world, and he attributes at least part of that wrongness to people wanting to do something other than what is right. Put another way, Eddie thinks that what's wrong with the world is that people want to do the wrong thing.

I think that Rand genuinely believed that a great deal of evil in the world was attributable to the conscious decision to do evil, and I think that that idea, that people choose to do wrong, is at the root of the flaws in her worldview.

One of the major flaws with libertarianism and/or objectivism is the unwillingness to concede that the choice to act in your own best interests may well do harm to others. This is remarkable, considering how terribly wounded the ideology is, and how much contempt it holds for self-interest in collective contexts.

*"matryoshka of cuckoldry" is the tag that will be used to mark posts that discuss the fascinating and bizarre world of sex and relationships in Rand's work. Eddie Willers is not Dagny's partner at any point in the novel but he is the most passive, distant, and mentally/physically/capitally weak of the men who love Dagny Taggart in the novel.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you'd like to read along with my read-through, this is the edition that I'm using so you can follow the page numbers.

Atlas Shrugged Read-Through Progress:

Announcement

Pages 11-14

Pages 14-20

Pages 20-

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlas Shrugged Read-Through Announcement

Okay folks, here we go.

I'm re-reading Atlas Shrugged so that you don't have to. Each post will cover only a few pages of the book and together we will explore Rand's prose, porn, and philosophy as we follow our cast of loveable industrialists through the mind on strike.

Background on who I am and why I'm doing this:

I'm Alli. I'm also known as @ms-demeanor on tumblr. I grew up in a libertarian household and read Atlas Shrugged for the first time at 18. I was obsessed with it and continued to vaguely align with libertarian politics until I was in my mid twenties, at which point it became impossible to ignore the fact that libertarian politics are morally bankrupt and philosophically hypocritical (I maintain that there are weed/abortion/gay marriage libertarians out there who still have their hearts in the right place, but they aren't the ones hyping up 'voluntary' slavery on Mises Institute forums).

Now I'm an anarchist. This is unsurprising, as it seems like people who were libertarians in the 2010s have done an 80/20 split between fascists and libertarians.

I'm also someone with a BA in English Lit and I continue to find Rand's writing compelling while I find her philosophy repulsive.

My goal here is to examine both of those things while also exploring the appeal that Rand's objectivism holds for people who aren't horrible monsters (and why it doesn't hold up to any scrutiny).

If this is the kind of nonsense you'd like to subject yourself to please feel free to follow this blog for updates. If you'd like to *avoid* this, go ahead and block the tag "#atlas shrugged read-through" to avoid it.

For updates or links to progress, check out the pinned post on this blog, where each read-through post will be linked.

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

im so mad bc “atlas shrugged” is such a raw fucking title. thats an EXCELLENT name for a book. a man holding the weight of the entire world on his shoulders is so moved by his disdain for the current state of things that he exerts the force to shrug. indifference to the nth degree. that’s fucking metal. then you read it and it’s just about hating poor people.

144K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm doing history homework and I'm running late so I'm going to have to leave the frantic quest to figure out whether or not Ayn Rand had heard of Dr. John Galt, caregiver at the first publicly funded psychiatric hospital in America, when she wrote Atlas Shrugged until later.

136 notes

·

View notes