Text

Hito SteyerlIn Defense of the Poor Image

The poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.

The poor image is a rag or a rip; an AVI or a JPEG, a lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances, ranked and valued according to its resolution. The poor image has been uploaded, downloaded, shared, reformatted, and reedited. It transforms quality into accessibility, exhibition value into cult value, films into clips, contemplation into distraction. The image is liberated from the vaults of cinemas and archives and thrust into digital uncertainty, at the expense of its own substance. The poor image tends towards abstraction: it is a visual idea in its very becoming.

The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its filenames are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self. It mocks the promises of digital technology. Not only is it often degraded to the point of being just a hurried blur, one even doubts whether it could be called an image at all. Only digital technology could produce such a dilapidated image in the first place.

Poor images are the contemporary Wretched of the Screen, the debris of audiovisual production, the trash that washes up on the digital economies’ shores. They testify to the violent dislocation, transferrals, and displacement of images—their acceleration and circulation within the vicious cycles of audiovisual capitalism. Poor images are dragged around the globe as commodities or their effigies, as gifts or as bounty. They spread pleasure or death threats, conspiracy theories or bootlegs, resistance or stultification. Poor images show the rare, the obvious, and the unbelievable—that is, if we can still manage to decipher it.

0 notes

Photo

Master photomanipulaion artist Erik Johansson takes pictures of everyday life and then retouches them in such a way that the scenes appear out of this world. Is that man really paving a roadway? Is water actually dripping from that picture frame? In his words, Johansson fuses the “problem solving part” of his brain with the “visual part” to create a holistic picture. “I always see my work as troubleshooting,” he says. “How can I create something that isn't there but make it look like it is?” The game-changing moment of inspiration arrived in 2000, when he first got his hands on a digital camera. “That's when I discovered digital manipulation,” he says, “and that I could create something that wasn't actually there.”

0 notes

Photo

When she was just six-years-old, Katerina Plotnikova began taking painting lessons. In college, she specialized in advertisement design, which was when she was first introduced to photography. Fast forward a few years, and now, the Moscow-based photographer takes whimsical portraits of young women alongside mammals like bears, elephants, and giraffes. With the help of professional trainers, Plotnikova captures models interacting with live animals. Her fascinating, fairytale-like photos mimic a princess lost in a magical forest. There is no post-processing done in Photoshop, save slight color correction. “All of my passion towards painting – and my years of academic art training – have helped me to discover a new form of art,” she says. “Though, I think my vision was with me all the time. I've always shown the world as I see it.”

0 notes

Text

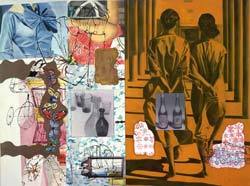

Yinka Shonibare MBEWhile not new to fabric as an artistic medium, Yinka Shonibare had the freedom during his residency at the FWM to create custom print designs for the textiles that would clothe figures in a new installation. Titled Space Walk, the installation ventures into the new frontier of American exploration—space. A man and woman—dressed in brightlycolored space suits, and wearing backpacks and helmets—float near a half-scale fiberglass and wood copy of the Apollo 13 shuttle. Pioneers of space, the couple refashions concepts of expansion, exploration, and potential colonization.

Shonibare designed four new fabrics for Space Walk. Based on the Dutch waxprinted batiks he has often used in previous work, the new designs recreate a batik patterning not through the traditional wax method, but through silkscreen printing. Two batik designs were created—one based on a traditional batik drip patterning, the other on a grid—and they were used as background for the printed textiles. The handmade quality of the prints was emphasized by printing the repeat pattern off-register; in other words, with each printing of the design, the silkscreen was allowed to move so the patterns do not align perfectly. The dominant motifs—drawn from the late 1960s and early 1970s music tradition produced in Philadelphia, known as the “Philly Sound”—are layered on the batik background. The artist borrowed images, text, and photographs from record albums of such period bands as The Intruders, Three Degrees, The O’Jays, and Contemporary singer Jill Scott. Shonibare made a master drawing, which was then transferred to silkscreens for printing. Characteristic of Shonibare’s work, the colors of the textiles are vibrant oranges, turquoises, and reds, another reference to the Dutch wax fabrics on which the designs are based.

0 notes

Text

Yinka Shonibare

Yinka Shonibare MBE RA (born 1962) is a British-Nigerian artist living in the United Kingdom. His work explores cultural identity, colonialism and post-colonialism within the contemporary context of globalisation. A hallmark of his art is the brightly coloured Dutch wax fabric he uses. Because he has a physical disability that paralyses one side of his body, Shonibare uses assistants to make works under his direction.

0 notes

Text

ztm_oruaml- Mauro C. Martinez

ztm_oruamI recently started making these sky paintings overlaid with a strip of safety orange spray paint. The sky is painted very similarly to those formulaic dreamscapes you see being painted live on street corners in metropolitan areas. Im intrigued by the idea of something so vast and infinite being reduced to something systematic and manageable. The safety orange, specifically designed to stand in contrast to the azure sky, simultaneously exists as a marking of territory as well as an act of vandalism. It represents the process by which we try to fathom the unfathomable or rationalize the irrational.

0 notes

Text

Picasso (1881-1973) and Duchamp (1887-1968) were more or less contemporaries. Both artists lived to a ripe old age and had strong links to Paris and European modernism, and both are referred to as 'artists of the 20th century.' Despite this, the two developed, artistically speaking, into almost diametric opposites.

Duchamp's name is well known and highly regarded within the inner circles of art and art institutions, although he is less known in more peripheral, art-interested circles. One of the reasons for this is probably that Duchamp's total production is quite limited and most of his works have been donated to a single museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. This means that it is not possible to study some of Duchamp's works in the original, or in reproduction, anywhere in Denmark.

0 notes

Text

PHILADELPHIA — “Marcel, Marcel, I love you like Hell, Marcel.” So ran a mash note written to Marcel Duchamp in 1923 by the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, one of the scores of women, and many men, for whom Duchamp was a personal fixation, erotic, aesthetic or otherwise.

For many contemporary art lovers he is a fixation still, the archangel of a once and possibly future avant-garde and a patron saint of postmodernism. And the Philadelphia Museum of Art, rich with relics of his sly, seductively standoffish spirit, is a pilgrimage site.

The 1912 painting “Nude Descending a Staircase,” Duchamp’s first succès de scandale, is here. So is “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” (1915-23), also called “The Large Glass,” a see-through mural about mechanized love and erotic frustration. And then there are the “erotic objects,” paperweight-size things molded from the body’s intimate nooks and crevices.

Duchamp’s great monument to eros, though, is the tableau called “Étant Donnés: 1. La Chute d’Eau, 2. Le Gaz d’Éclairage” (“Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas”). Created in almost complete secrecy between 1946 and 1966, it was his final work, and also his weirdest and most mysterious. And it is the subject of a potent exhibition at the museum called “Marcel Duchamp: Étant Donnés,” which, among other things, finesses the lingering myth that Duchamp ended up abandoning art for a life of chess and cogitation.

In reality, and by his own description, he simply went “underground.” He went on with his very active art-world social life, but told almost no one about the art he was making. He left the completed “Étant Donnés” in his bare-bones Manhattan studio when he died in 1968. The next year it was placed, as he had assumed it would be, on permanent view in the Philadelphia Museum gallery dedicated to the big cache of his work that came to the museum with the Arensberg collection in the 1950s. The gallery has been reinstalled with new material, much of it never before exhibited, to create the present show.

Jasper Johns, a longtime Duchampian, once referred to “Étant Donnés” as “the strangest work of art in any museum.” And strange it is. It occupies a closed-off room in a dead-end area at the back of the main Duchamp gallery. The room can’t be entered. The entrance is blocked by a pair of locked antique wooden doors, solid except for two tiny side-by-side peepholes in their center.

When you look through the holes — only one person at a time can do so, making for a very self-conscious viewing experience — you see a shattered brick wall just beyond the door, and in the distance a painted landscape of hills, autumn-tinged trees and what appears to be an actively flowing waterfall.

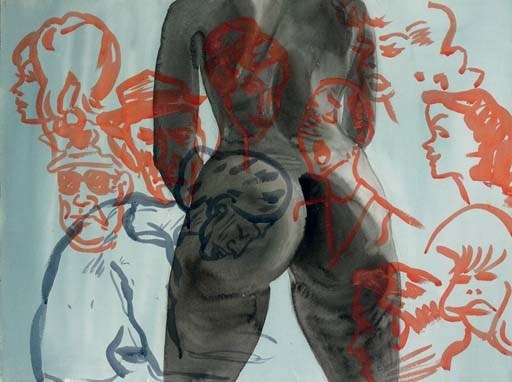

In the foreground, just past the shattered wall, the nude body of a woman reclines on a nest of dried branches, her legs spread wide to reveal oddly malformed genitals. Her face is obscured by her blond hair. Her lower legs and right arm are out of the range of vision. Her left arm is raised at the elbow, and in her hand she holds a small, glowing electric lamp.

The sight, at once bucolic and freakish, provoked an uproar when the piece had its public debut 40 years ago. What are we looking at? The aftermath of rape, mutilation and attempted murder? A profane update of Bernini’s “Ecstasy of St. Teresa”? (Duchamp sometimes referred to the figure as “Our Lady of Desires.”)

Either way, it must have struck some feminists as one more addition to art history’s archive of aggression against women. And these viewers would have found small comfort in learning that the piece was conceived as a kind of erotic homage to two specific women in Duchamp’s life.

One was the Brazilian-born sculptor Maria Martins, with whom he had an affair from 1946 to 1951. His art went wild during that time. The “erotic objects” proliferated. He made paintings from semen and collages from body hair. The nude in “Étant Donnés” is largely pieced together from casts of Martins’s voluptuous figure. She was both the object of the work and a collaborator: Duchamp consulted her repeatedly as the work progressed.

The other woman was Duchamp’s second wife, Alexina, known as Teeny, whom he married after the Martins affair, in 1954. It is a cast of her hand that holds the electric lamp in the tableau. She was privy to every step in the progress of the piece as it evolved toward completion.

It is the making of “Étant Donnés,” rather than its enigmatic meaning, that this exhibition focuses on. Michael R. Taylor, curator of modern art at the Philadelphia Museum, essentially gives us a detailed backstage tour of the fabrication process, a tour all the more intriguing for being devoted to an artist who, it is often said, came to disdain all creative tools apart from ideas.

Proof to the contrary is here. Almost every surviving scrap of physical material related to “Étant Donnés” has been gathered, either from the museum’s deep Duchamp archives or from other collections. From 1946, early in the piece’s history, comes a highly polished pencil drawing of Martins’s nude body; later come plaster casts of her limbs and samples of “skin” made from parchment, all evidence of Duchamp’s fascination with craft and the naturalistic effects it could achieve: flesh that was smooth but not slick; skin that looked warm but not too flushed.

The background landscape was a similar blend of artifice and realism. The scene originated in photographs Duchamp took on a vacation in Switzerland. He enlarged the prints, cut them up and rearranged them to eliminate any evidence of buildings. After photographing and printing the altered panorama on cloth, he meticulously colored it with oil paint and chalk. He made the “moving” waterfall from translucent plastic backed by rotating discs powered by a motor housed in a biscuit tin.

The illusion of space and atmosphere seen in the peephole view is remarkable, especially given the out-of-sight construction that produces it, a ramshackle exercise in bad carpentry and precarious wiring, with pieces of drapery held in place by clothespins. It’s all documented in a series of Polaroids Duchamp took of the nearly finished piece in 1965, when he learned that the lease on his longtime studio in Manhattan wasn’t being renewed and that he had to move everything to a different space.

The Polaroids, being exhibited publicly for the first time, left me a little breathless. They are documents, not of a fabled retirement, not of cerebral dandyism, but of effort, effort, effort, and the strain and anxiety Duchamp was under as he began to form, through photographs, the rudiments of an instruction manual for dismantling and reassembling the flimsy product of nearly 20 years’ work.

The same dynamic of effort animates Mr. Taylor’s exceptional catalog, which weighs a scholarly ton but is as absorbing to read as a whodunit. I wolfed it down, transfixed, in a night and a day.

It covers not only, step by step, the two decades of the tableau’s creation, but also the minutiae of its delicate transfer to Philadelphia, an operation overseen by a young curator named Anne d’Harnoncourt, who a few years later would help to organize the museum’s great Duchamp retrospective and would then serve as the institution’s much-admired director from 1982 until her sudden death last year.

Both the book and the exhibition are dedicated to her. And both include something she would have liked: work by contemporary artists for whom Duchamp, and “Étant Donnés” in particular, has been an inspiration. Robert Gober and Marcel Dzama are among those covered in the catalog. Ray Johnson is in the show, with some snappy mail-art drawings that filter Duchamp’s piece through a homoerotic lens — quite plausibly, given Duchamp’s efforts to scramble conventional gender categories in his work.

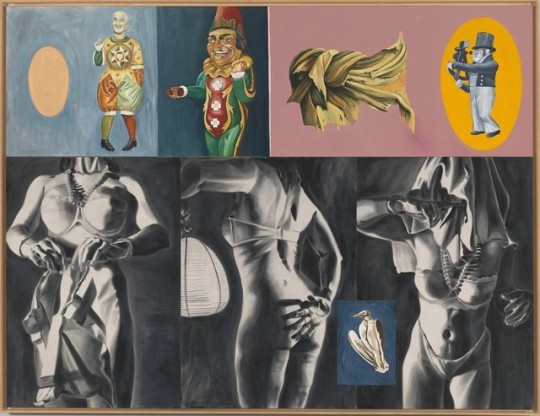

And there is a film by a contemporary female artist, Hannah Wilke (1940-93), who went to art school in Philadelphia, saw “Étant Donnés ” soon after its installation and remembered finding it “repulsive.” She later did a performance about it in which she assumed the place of the prone figure. And in a 1976 film made in the museum’s Duchamp gallery, she engaged with “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” his other grand erotic masterwork.

Dressed in a high-fashion white tailored suit and fedora, she does a slow striptease in front of the piece, or rather behind it, as the camera shoots her performance through the glass and through Duchamp’s painted phallic and vaginal forms frozen in unconsummated union.

Wilke, who was a great beauty, preens, shifts, undoes a button, tips her hat, shifts, stares, slowly pulls at a zipper. The Bride and the Bachelors can never complete their erotic task, but she can. In her performance she was the cool but active counterpart to the woman in “Étant Donnés,” just as exposed but in control of the exposure.

Duchamp, the transcendent pornographer, would have understood all these contradictions. I suspect he saw himself both as the distanced creator of his final work and as the passively light-bearing figure lying within it. And surely he would have agreed with Wilke’s tough-love words: “To honor Duchamp is to oppose him.” Because he opposed himself — or the mythical self he invented — by slaving away at material forms of art that he had declared beneath contempt. His dispassionate passion is what continues to make him magnetic. Tough self-love, perverse and seductive, is what “Étant Donnés” is about.

0 notes

Text

Marcel Duchamp Étant donnés

In his early thirties, Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) convinced everyone that he had abandoned making art in favor of playing chess. But from 1946 to 1966, he was secretly at work in his studio on West Fourteenth Street in New York City. There he produced his final masterpiece:

Étant donnés: 1º la chute d’eau, 2º le gaz d’éclairage

, composed of a battered wood door through which one views a prone, nude female, holding aloft an antique gas lamp against a landscape of trees, waterfall, and sky. Unveiled as a permanent installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in July 1969, the year after Duchamp’s death, the work startled the art world with its explicit eroticism and voyeurism, as well as its trompe l’oeil realism. Since its public debut, Étant donnés has been recognized as one of the most important and enigmatic works of the twentieth century.

0 notes

Text

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même), most often called The Large Glass (Le Grand Verre), is an artwork by Marcel Duchamp over 9 feet (2.7 m) tall, and freestanding. Duchamp worked on the piece from 1915 to 1923, creating two panes of glass with materials such as lead foil, fuse wire, and dust. It combines chance procedures, plotted perspective studies, and laborious craftsmanship. Duchamp's ideas for the Glass began in 1913, and he made numerous notes and studies, as well as preliminary works for the piece. The notes reflect the creation of unique rules of physics, and myth which describes the work.

0 notes