Text

One of my favorite “doing things with words” techniques is this thing that Tolkien did a lot where you describe sweeping action with a lot of long, dramatic, byzantine sentences and then end the passage with a v. short simple sentence or sentence fragment. Like this bit from The Silmarillion:

Then Fingolfin beheld… the utter ruin of the Noldor, and the defeat beyond redress of all their houses; and filled with wrath and despair he mounted upon Rochallor his great horse and rode forth alone, and none might restrain him. He passed over Dor-nu-Fauglith like a wind amid the dust, and all that beheld his onset fled in amaze, thinking that Oromë himself was come: for a great madness of rage was upon him, so that his eyes shone like the eyes of the Valar. Thus he came alone to Angband’s gates, and he sounded his horn, and smote once more upon the brazen doors, and challenged Morgoth to come forth to single combat. And Morgoth came.

955 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last time I read Lord of the Rings, I particularly focused on the songs and the lore that they communicated. Now that I've re-read The Silmarillion, which establishes that this universe was created from song, the music in LotR takes on a new dimension. The whole history of this world is recorded in the lyrics, with successive generations building onto the story, right up to Bilbo and Sam composing verse at the end of the Third Age. Participating in the act of creation.

708 notes

·

View notes

Text

ALSO thinking about how tolkien spent his whole life studying the textual remnants of old stories and their translation and the nature of how those stories are passed on, and then wrote his own stories based on those stories that themselves explore the nature of what it is to be stories, complete with internal textual transmission and oral tradition and examination of what it is to be remembered, and then after his death those stories now have their own textual history, full of manuscript errors and revisions and missing pieces and retellings. like the uncertainty inherent in storytelling, and particularly the uncertainty in the act of recording them that he condensed into the internal narrative of the text ended up refracted back out onto the stories he wrote themselves

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Narrative Power in Arda

An embarrassing number of months ago, I alluded to narrative as an in-universe force within the Silmarillion in my tags on a post I have since lost, which I feel merits further elaboration. The short version is that crafting a story carries meaningful weight and power in Arda, which is not much of a reach considering that 1) telling a story in a certain way has power even in the real world, and 2) music is already well-established as an important medium and means of magic in Middle Earth. I think it is relevant to consider this aspect when discussing the nature and weight of words in the Silmarillion, whether it be curses, dooms, oaths, or anything else.

To begin with, it is difficult to tease apart what I will call in-universe narrative from narrative in the sense that a guy called Tolkien wrote this whole story down, on purpose, with various story arcs that come to various narratively satisfying conclusions. The best illustrative example of in-universe narrative, thus, is Finrod’s duel in song against Sauron, because Tolkien could have had the song battle work however he wanted, but he chose to make it about storytelling. We joke about Finrod and Sauron’s rap battle, but their contest really is a battle of narratives – particularly cultural narratives. To quote:

Then sudden Felagund there swaying

Sang in answer a song of staying,

Resisting, battling against power,

Of secrets kept, strength like a tower,

And trust unbroken, freedom, escape;

[…]

And all the magic and might be brought

Of Elvenesse into his words.

[…]

The sighing of the sea beyond,

Beyond the western world on sand,

On sand of pearls in Elvenland.

This is arguably the story of the Noldor, as told by Finrod – all the beauty and power of Aman, but brought by the Noldor to Middle Earth in their flight to escape the control of the Valar and avenge their king against Morgoth’s evil. This is his choice of story to wield against Sauron, and it makes sense. It invokes the Noldor’s heroism against Morgoth in maintaining the long siege, as well as their rejection of all the higher powers and his own faithfulness to his oath to Barahir that led him to this point. It’s a good story, but Sauron shatters it with a single invocation, because this narrative Finrod spins of the Flight of the Noldor cannot accommodate the atrocity that was the Kinslaying at Alqualonde.

The outcome of the song battle is not decided based on raw power, or skill in crafting magic or spells, or even singing ability. It is won on the merits of narrative: Finrod’s story doesn’t work; he cannot narratively reconcile the reality of the Kinslaying with “trust unbroken, freedom, escape,” and thus Sauron has the victory (1). Thus, we can conclude that “does the story work” is a legitimate part of how magic functions in Middle Earth.

This should not come as a surprise; Middle Earth (and the world itself) were created/predicted by the Music of the Ainur, which is itself a narrative work of music. It, arguably, puts the story in history (2). The narrative of the Ainulindale, moreover, is disrupted by Morgoth in much the same way Sauron disrupts Finrod’s narrative in their contest. But whereas Finrod’s story collapses under the contradictions introduced by Sauron, Eru incorporates Morgoth’s discord into the Music to create a new, greater theme than the one before. This is not an accident, and it shows that Eru, as God and Creator (read: Author), understands narrative better than Morgoth does: any good story has conflict of one sort or another. That’s what makes them stories, rather than a pleasant but boring account of a series of pleasant but boring events.

This is to say, Tolkien makes the necessity of having a plot arc into part of his theological worldbuilding. There is, frankly, a lot you could say about that, but I am not going to, because it is somewhat off-topic from the point I’m trying to make and also I really don’t know where to begin.

Additionally, while Finrod’s own narrative fails, the overall narrative of Middle Earth picks up where he left off and turns his defeat into a fourth-act crisis point, the abyss which makes way for Luthien’s subsequent victory over both Sauron and Morgoth and triumphant retrieval of the Silmaril. Finrod may not have known how to turn Sauron’s narrative disruption to his own ends, but Eru does.

Returning to the Doom of the Noldor, while Manwe is said to be the closest of the Valar to Eru in thought, I would argue that Namo, as the Vala of fate, is the closest of the God-as-Author aspect of Eru. His domain, fate, is closely linked with the Music. I said earlier that Middle Earth was created/predicted by the Music, and that blurriness between creation and prophecy is important for understanding the nature of Fate in Tolkien’s work - there is a careful tightrope walked between free will and determinism (3). I argue that the Music additionally suggests that fate in Arda is really Narrative at work.

So where does that leave, for instance, the Doom of the Noldor? Is it curse or prophecy? Punishment meted out by the gods or natural consequences of an unprecedented violent attack? Framing it in these binaries is reductive no matter which side you come down on. The Doom is neither a curse nor a prophecy: it is a narrative.

The soon-to-be Exiles, led by Feanor, kick off their narrative in maybe the worst way possible (murder). This is, objectively, a very bad inciting incident – stories that start with murder don’t tend to turn out well for the people doing the murdering. Within the Music, and the fabric of Arda’s fate, the Noldor have narrowed their narrative options significantly. “Slain ye may be, and slain ye shall be,” for have they not already slain their own kin? But it is very difficult to argue for the Doom as purely prophetic. The text itself indicates in multiple places the judgment or wrath of the Valar as something laid upon the house of Feanor and all who follow them, not simply natural consequences. There is a tangible weight to the Doom, and a sense after the War of Wrath that it is something that can be lifted.

Mandos says, you have chosen your story to be a tragedy by opening with a tragedy. But when this is spoken by Narrative himself, it takes on a weight greater than that of a mere prediction. The Doom defines the genre of the story that is to follow: Tears unnumbered ye shall shed. And they did.

The story, of course, is never truly over. But I’ll leave eucatastrophe for another day.

Footnotes:

(1) As a side note, I am forever thinking about arrogantemu’s fic “Beyond the Western World,” in which Finrod says “I’d staked everything on an innocence I didn’t have.” Credit where credit is due for influencing my thinking on this subject.

(2) Tolkien as a linguist would undoubtedly be aware that the words come from the same root, and that other modern languages have not in fact separated the meanings of “work of fiction” and “account of real events” into separate words.

(3) To write a proper meta on this subject I would have to dig much deeper into other sources, but from my understanding fate in Tolkien’s works works very similarly to the Anglo-Saxon concept of wyrd – there’s a very interesting line in Beowulf, I believe, about how “for undaunted courage, fate spares the man it has not already marked” (paraphrased). I highly recommend reading more about it for a better understanding of fate in Middle Earth.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tenth-century-or-earlier Old English poem Deor is great because it's just the poet going "my problems are just like when Blorbo from my legends had problems" and providing a long list of names of people in vaguely-described situations.

And then modern scholars have to read it like "we have literally barely heard of any of these guys, who even are they" because it's been a thousand years and several massive culture shifts, and some of the poet's blorbos now only survive in his references to them.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

tolkien being catholic an orphan and also having most of his friends dead by age 25 is really the perfect blend of trauma to make a great author 👍

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

“We are all familiar with the term suspension of disbelief. At a guess, less of us know secondary belief. It’s a Tolkienism that he used in a way quite similar to how we use suspension of disbelief – that we look at all the impossibilities and instead of laughing, think “well that’s just how it works here”. For Tolkien, the difference is that secondary belief is what is just happens, and suspension of disbelief is what happens when secondary disbelief fails and the reader has to make a conscious decision whether to keep acting like it’s there.”

—

SECONDARY BELIEF VS SUSPENSION OF DISBELIEF

An important point here about worlds.

We don’t suspend our disbelief when we enter an online/virtual world. We are invited to belive in them.

If anyone is interested in further reading on Tolkien and his position on secondary belief and world building, the opening chapters of Building Imaginary WorldsThe Theory and History of Subcreation by Mark J.P. Wolf is a good place to start.

8 notes

·

View notes

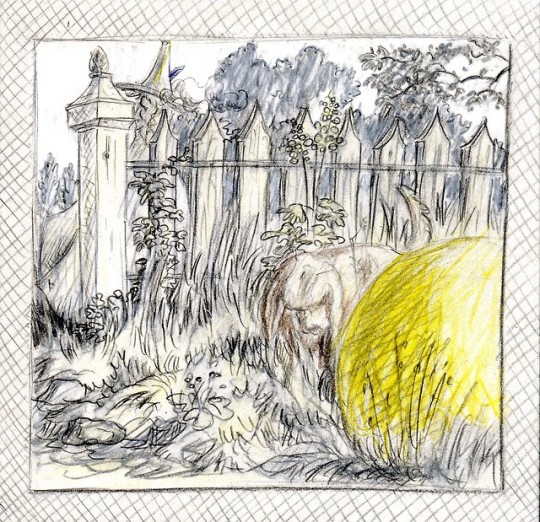

Photo

Illustrations for Roverandom by J.R.R. Tolkien

pt. 1

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.”

-J.R.R. Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Man, Sub-creator, the refracted light through whom is splintered from a single White to many hues, and endlessly combined in living shapes that move from mind to mind. Though all the crannies of the world we filled with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build Gods and their houses out of dark and light, and sowed the seed of dragons, ‘twas our right (used or misused). The right has not decayed. We make still by the law in which we’re made.”

— J. R. R. Tolkien, Mythopoeia

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Probably every writer making a secondary world, a fantasy, every sub-creator, wishes in some measure to be a real maker, or hopes that he is drawing on reality: hopes that the peculiar quality of this secondary world (if not all the details) are derived from Reality, or are flowing into it. If he indeed achieves a quality that can fairly be described by the dictionary definition: “inner consistency of reality,” it is difficult to conceive how this can be, if the work does not in some way partake of reality. The peculiar quality of the ”joy” in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth. It is not only a “consolation” for the sorrow of this world, but a satisfaction, and an answer to that question, “Is it true?” The answer to this question that I gave at first was (quite rightly): “If you have built your little world well, yes: it is true in that world.” That is enough for the artist (or the artist part of the artist). But in the “eucatastrophe” we see in a brief vision that the answer may be greater—it may be a far-off gleam or echo of evangelium in the real world. The use of this word gives a hint of my epilogue. It is a serious and dangerous matter. It is presumptuous of me to touch upon such a theme; but if by grace what I say has in any respect any validity, it is, of course, only one facet of a truth incalculably rich: finite only because the capacity of Man for whom this was done is finite…It is not difficult to imagine the peculiar excitement and joy that one would feel, if any specially beautiful fairy-story were found to be “primarily” true, its narrative to be history, without thereby necessarily losing the mythical or allegorical significance that it had possessed. It is not difficult, for one is not called upon to try and conceive anything of a quality unknown. The joy would have exactly the same quality, if not the same degree, as the joy which the “turn” in a fairy-story gives: such joy has the very taste of primary truth. (Otherwise its name would not be joy.) It looks forward (or backward: the direction in this regard is unimportant) to the Great Eucatastrophe…God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves…But in God’s kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on…So great is the bounty with which he has been treated that he may now, perhaps, fairly dare to guess that in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation. All tales may come true; and yet, at the last, redeemed, they may be as like and as unlike the forms that we give them as Man, finally redeemed, will be like and unlike the fallen that we know.

J. R. R. Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories”

4 notes

·

View notes

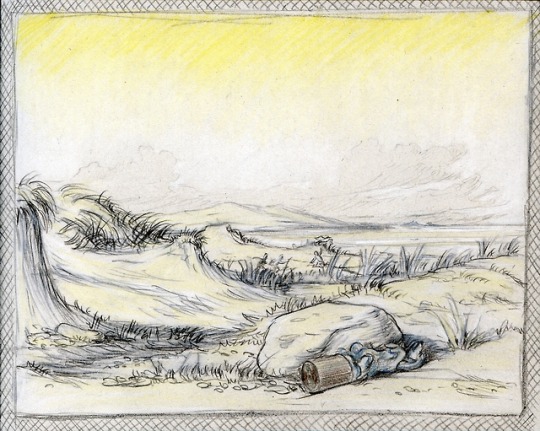

Photo

The scars of World War I.

▲▼

Grass covered trenches and craters from exploded bombshells, Battle of the Somme

The Lochnagar Crater, nearly 70 feet deep, was formed after an explosive-packed mine was detonated during the Battle of the Somme.

The tiny village of Butte de Vaquois once stood on a hilltop, and was destroyed after three years of furious mining blew away its summit.

Photos: Michael St. Maur Sheil

991 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘One who dreams alone’

from John Garth’s postscript to Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth

“ A pale drawn man sits in a convalescent bed of a wartime hospital. He takes up a school exercise book and writes on its cover, with a calligraphic flourish: ‘Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin’. Then he pauses, lets out a long sigh between the teeth clenched around his pipe, and mutters, ‘No, that won’t do anymore.’ He crosses out the title and writes (without the flourish): ‘A Subaltern on the Somme’.

That’s not what happened, of course. Tolkien produced a mythology, not a trench memoir. Middle-earth contradicts the prevalent view of literary history, that the Great War finished off the epic and heroic traditions in any serious form. ….[D]espite its unorthodoxy—and quite contrary to its undeserved reputation as escapism—Tolkien’s writing reflects the impact of war; furthermore…his maverick voice expresses aspects of the war experience neglected by his contemporaries. This is not to say that his mythology was a response to the poetry and prose of his contemporaries, but that they represent widely divergent responses to the same traumatic epoch. ”

Keep reading

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Essential viewing for any Tolkien fan who is interested in the impact of the Great War on Tolkien and his closest group of friends.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our memory of Smith is burdened with poignancy. He survived the entire five-month Battle of the Somme only to be hit by shrapnel from an exploding shell days after the battle had finished and miles from the trenches. The wound was so light that he walked to the casualty clearing station. Three days later he was dead from an infection, gas gangrene.

His would seem just another of the innumerable futile deaths in that futile war but for the fact that it gave retrospective force to a letter he had sent Tolkien months earlier, telling him: ‘May God bless you, my dear John Ronald, and may you say the things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them, if such be my lot.’ He was thinking of Tolkien’s invented mythology, of which Smith declared himself ‘a wild and wholehearted admirer’ – the first Middle-earth fan.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“So we lay down the Pen”

So we lay down the pen,

So we forbear the building of the rime,

And bid our hearts be steel for times and a time

Till ends the strife, and then,

When the New Age is verily begun,

God grant that we may do the things undone.

— Geoffrey Bache Smith, Spring Harvest, ed. JRR Tolkien

1 note

·

View note