Text

Hidden treasure at the Sindh Archives

Feature published in The Friday Times.

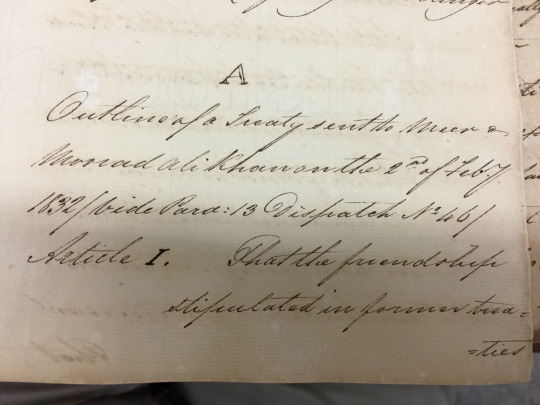

A faded, brittle manuscript titled “Secret Department”, signed “H. Pottinger” and dated “3rd February, 1832” quotes Mir Murad Ali Talpur. “‘We know nothing’, said His Highness, ‘about accounts, or traffic, or writing. We hardly know that two and two make four. We all trust to Hindoos to bring us what we want from abroad, and our business is to fight amongst each other, which we do daily.’” Pottinger’s handwritten letter, addressed to the Governor-General’s secretary, details his day-to-day conversations with the ruler of Sindh eleven years prior to conquest. The letter goes on to provide an “Outline of a treaty sent to Meer Moorad Ali Khan on the 2nd of February, 1832”, under which the Indus was to be opened up for ‘trade’.

This is a sample of the treasure waiting to be dug up in one of Old Clifton’s tamarisked dead-ends. The Sindh Archives building lies tucked away behind Federation House and Park Towers, in Karachi. It contains correspondence and reports, the earliest of which date back to the 1830s, providing first-hand accounts of life in colonial Sindh – in the kind of vivid detail not found in history books. It also hosts a collection of old maps and rare books.

It is these very records that British historian David Cheesman accessed during his PhD research, which formed the basis for his work Landlord Power and Rural Indebtedness in Colonial Sind 1865-1901 (1997, Curzon). Recalling his experience of the archives, Dr Cheesman tells me “In 1976-77, when I carried out my PhD research, the records were stored in the Commissioner’s Record Office, which came under the Commissioner of Karachi. Access was at the Commissioner’s discretion. I had to convince him that I was only interested in people who were long dead. The records staff used to bring me my dusty bundles of old papers from the nineteenth century while they got on with their main business of filing modern records. Because the work of the Karachi administration was going on around me, it really felt as if I was in the old ‘Sind Commission’.”

“What I found especially fascinating” recalls Dr. Cheesman, “was that they still had stores of unsold official publications and so long as they had sufficient copies in the archive, they were very sensibly selling off the unwanted duplicates – at the original prices. So, for example, I got the 1933 guide to ‘Sind Government Records’ for 12 annas(i.e. Rs 0.75), the 1954 Bund Manual for Rs 5 and various British settlement reports. Selling them was certainly more cost effective than the alternative, which would have been to destroy them. When I came away clutching the 1918 settlement report for Thul, Kandhkot and Kashmore, for example, I really felt time had stood still!”

Old records of the commissioner in Sindh are filed under the following classifications: revenue, judicial, administrative, political and miscellaneous. In addition, there are the proceedings of the September 1929 session of the Legislative Assembly of India (the same assembly that had been bombed by Bhaghat Singh and BK Dutt six months prior), the proceedings of the Bombay Council from 1919 onwards and Bombay Government Gazettes from as early as 1850.

It is the records of the British – who left no stone un-surveyed – that largely make up the archives. However, according to historian Hamida Khuhro, “Prior to the British period, a lot of people in Sindh who engaged in scholarly pursuits valued their manuscripts. There are families that have a collection of handwritten manuscripts: written by their ancestors, or by someone who would write on their behalf. Therefore, there was a tradition of collecting old material.” The Sindh Archives have a 450-year-old Persian manuscript and more in Arabic.

While it is the archives that are the ‘treasure’ and not the building itself, one cannot help but wonder whether its architect anticipated it as a blank canvas on which you could build your historical imagination. Built in 1988, the complex has an unfinished feel to it. Perhaps the way Karachi felt in its early days. Or the way parts of the city still feel.

Architect Navaid Husain says, “It is a naive building. I was young when I designed it. At this age I am of the view that it should have been a historic building.” Yet, somehow, its appeal lies in the fact that it does not demand appreciation. The wide-open spaces and a lack of theme are filled up by images of the history you uncover in the archives. You associate the smell of the building and the old documents with the period under study.

Hamida Khuhro argues, “The building is very badly placed. It’s near the sea; it is humid and absolutely destructive of paper. It should be shifted to KDA or even further away. The weather is better there, believe it or not.”

The manuscripts are fumigated, chemically treated, bound and stored in acid-free boxes. The stack area is the only area I’ve seen in Karachi that is furnished with a functional (waterless) fire safety system. It is air-conditioned and the temperature and humidity are strictly monitored every three hours. Old newspapers, stored in another room, are undergoing preservation.

Akash Datwani, a qualified archivist and stack area in-charge, is highly efficient in facilitating researchers. He is the man to go to when carrying out research at the archives. Datwani has provided training in archival management to the Sindh Coastal Development Authority and to students of Karachi University’s MA program in Library and Information Sciences.

Sakhidad Kachelo, who worked at the Sindh Archives from 1979 until his retirement as an assistant director in January 2016, is a part and parcel of the relics found in the archives. “Part of the record used to be stored in Hyderabad,” he recalls, “and while it was there, a significant portion of it disappeared, or was stolen. The record was shifted to the current building in 1992. In 1993, Martin Moir, former deputy director of the India Office Library, gave us six months of training in record management.”

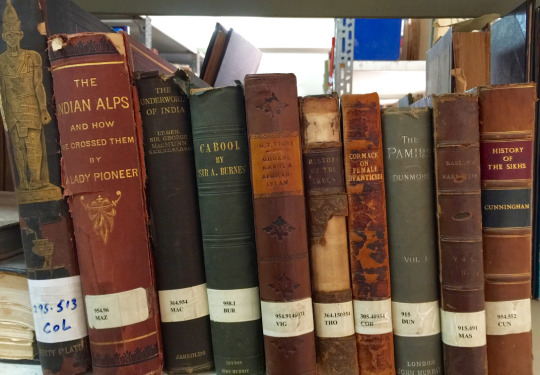

Three lanes down, the British Council library has re-opened its doors. The Sindh Archives – a ten-minute walk from there – may not have a cafe, but it does have the first edition of Joseph Davey Cunningham’s controversial A History of the Sikhs, published in 1849 by John Murray. A faded handwritten note in its front matter section reads “The rare first edition – suppressed upon publication on account of certain passages which gave offence.” On another shelf lies the first edition of Alexander Burnes’s Cabool, published in 1842 by John Murray. Its endpaper contains the signature of its first owner, dated May 1842. Nearby, is the first edition of Charles Masson’s Narrative of Various Journeys through Balochistan, Afghanistan, The Panjab, & Kalat, published in 1844 by Richard Bentley. There is also the first edition of the 7th Earl of Dunmore’sThe Pamirs, published by John Murray in 1893, with a silver Buddha embossed on its cover. Eye-catching titles such as, ‘The Indian Alps and How We Crossed Them by A Lady Pioneer’ and ‘A History of the Thugs’ cannot be missed.

However, the rare book collection – already in delicate condition – is located in a space where sunlight, heat, dust and humidity can wreak havoc on it. The rare books have been put into the same room as regular books, near large windows that are left open. It is evident that the adjustable open shelves on which the rare books are placed are not contributing to their preservation and are, if anything, damaging their covers. As the shelves are open from the sides, some books lying on the edge are leaning outwards.

When I first visited the Sindh Archives in 2007, the rare book collection was kept under lock and key in a windowless room specifically designated for it. A visitor needed permission to be able to view it. After Naeem Daudpota became the librarian in 2010, the collection was shifted to its current location. Daudpota, an MA in Library Information Science as well as History, explains, “It doesn’t make sense to keep rare books locked away and hidden from public viewing. On the contrary, people must be made aware of their existence and be encouraged to come and read them.” While such intentions are promising, accessibility must not come at the cost of preservation. The rare books must be shifted to an air-conditioned room, devoid of windows, where temperature and humidity are closely monitored – as is done in the stack area.

Referring to the personal collections in the library of the Sindh Archives, Hamida Khuhro opines, “I don’t think it is right that books in a library be organised under personal collections. They should be organised according to subject. Otherwise it is not helpful to researchers.”

The lone researchers that are seldom found in the corridors of the archives are either lawyers – compelled to visit for work – or foreign historians, or simply those driven by a carnivorous curiosity for an accurate picture of what was.

Colonel (retd) Hassan Imam, who has carried out research on his grandfather Wadero Ghulam Kadir Dayo, a landholder of Ratodero Taluka, tells me he is convinced that “Somebody has tampered with the Blue Book of Larkana District. The photocopy of the Blue Book preserved in the Sindh Archives is different from the one preserved in the Sindhology Institute, Jamshoro.” In my own research, I did notice that certain entries in the copy of the Blue Book in the Sindhology Institute were missing from the one in the Sindh Archives. According to Imam, “The pages covering the years 1901 to 1926 are missing. Furthermore, some entries that bear the signatures of different Collectors are all in the same handwriting. Whoever had an interest in destroying this record has deliberately done so.” According to Dr Cheesman however, “The handwriting may or may not be significant. Security was surprisingly lax in those days compared to now and, before photocopiers, even sensitive documents were frequently transcribed. You would probably be able to tell a lot from the style of writing – modern handwriting is very different.”

The past, encapsulated in the archives, is relevant, as are its missing pieces. Factual specifics, although limited, are more revealing than any vague, romanticised fable. Sensibilities and perspectives uncovered in old manuscripts relating to Sindh can provide history-lovers with a fresh perspective of the present: a new way of ‘seeing’ and understanding their current reality.

0 notes

Text

A forgotten kingdom

Feature published in Newsline.

On the edge of the desert in Khairpur District, a cluster of ghostly bungalows and ornate halls of audience make up the remnants of a royal court. They point to an earlier era of aesthetic fusion between East and West. Casting its protective shade over these is a hilltop fort. Its towering ramparts have gazed down at travellers for over two centuries.

These relics, camouflaged in dust in the village of Kot Diji, belong to the Khairpur branch of the Talpurs, who ruled Upper Sindh from 1783 till 1843. Thereafter, until Partition, they continued to reign over an autonomous Native State carved out for them by the British.

The approach to the village of Kot Diji from the old national highway is marked by a sudden change in topography. A flat and fertile alluvial plane is interrupted by the emergence of isolated hillocks. These limestone formations are part of a greater ridge of hills that runs south from Rohri, known as ‘Gharr.’ The sweltering heat of a May afternoon is overshadowed by a mountain of rainclouds moving in from Naara and the Indian border – the eastern peripheries of Khairpur District. Kot Diji is located at the exact spot where the fertile green plain that lies to its west gives way to the desert that sprawls eastward, to Jaisalmer and beyond.

After the Talpurs seized Sindh from the Kalhoras in 1783 and divided it up between themselves into three independent units, Mir Sohrab Talpur established his court in Khairpur. Having two sons from Talpur wives, Mir Sohrab took a third wife from the house of a Marri nobleman. This marriage gave birth to his youngest son, Mir Ali Murad I. In 1830, while at Sohrab Manzil in Khairpur, Mir Sohrab mysteriously fell off its balcony while watching a Muharram procession, and died soon after. The current members of his family suspect that he may have been pushed off. They feel it would have been particularly difficult to fall off a balcony that was surrounded by a chest-high brick wall.

Mir Mehdi Raza represents the current generation of the Talpur dynasty. He is the son of Mir Ali Murad II and a direct descendant of Mir Sohrab (seven times removed). According to Mir Mehdi, “Some members of the family took exception to Mir Sohrab adding his youngest son’s name to his will. The fact that his mother was not a Talpur made it unacceptable to them.” Nevertheless, Mir Sohrab’s youngest son, Mir Ali Murad I, ascended to the throne in 1842, the year General Charles Napier arrived in Sindh.

The more discerning visitor may notice that the old structures in Kot Diji and Khairpur, in all their magnificence, would not have made practical residences. And while today they may be passed off as ‘palaces’ or ‘bungalows,’ their owners confirm that with the exception of one or two, they were not meant to be living quarters, but darbars (courts). At the time they were built, their owners preferred living in tents.

Mir Mehdi told Newsline that up until (and including) his great-grandfather’s generation, living in tents was the norm for the Talpurs, who were nomadic Baloch tribesmen. “While women and children lived in houses,” he explains, “it was considered unmanly for men to do so.” The heat was never a problem, he says, as “these people were out hunting for most of the time, even in peak summer. Therefore, they were adjusted to the hot climate.” The tents were usually made of velvet, or in some cases, tiger skin, the latter having been gifted to Queen Victoria by Mir Ali Murad I. Mir Mehdi learnt of these habits from his father, who was told by his father, and in this manner, details of day-to-day living were handed down from one generation to the next. They are backed up by the memoirs of British travellers, who witnessed them first hand.

Edward Archer Langley, a former captain of the Madras Cavalry, spent a substantial period of time in the court of the then Rais (turban-holder), Mir Ali Murad I, in 1857-8. In his memoir, A Narrative of a Residence in the Court of Mir Ali Moorad, while commenting on the Mir’s bungalow in Kot Diji, Langley observes that the Mir “Never occupies the house; but passes his days in a Landee [shed] in front, and sleeps in a small tent close to the building.” Langley further notes, “His Highness… rarely sleeps three nights running in the same spot, for his habits are exceedingly nomadic, and even when in a city he generally sleeps in a tent.”

The bungalow Langley refers to, no longer exists. In its general vicinity stands Shahi Mahal. The previous bungalow, reports Langley, had interiors painted in fresco and was located “in the midst of a garden of… twenty acres, enclosed with a high wall.” Within this wall roamed numerous wild boars and crosses between wild boars and English sows, which would often charge at gardeners and court jesters alike, much to the amusement of the Mirs. The layout of this darbar, Langley describes, was similar to the old residency of the British political agent in Khairpur.

British explorer Charles Masson passed through Khairpur in 1829, while Mir Sohrab was still alive, and saw his court, Sohrab Manzil, from the outside. In his Narrative of Various Journeys, he notes that the Mir’s “palace” was located in the “the very centre of the bazaars,” that its boundary wall contained battlements, and that “from the exterior, the only prominent object is the cupola of the masjit [masjid], decorated with green and yellow painted tiles.” By the time Langley saw it, almost three decades later, “the ruinous old house,” which stood within “the crumbling walls of a mud fort,” had fallen into disuse and was completely empty. “As the place reminded Mir Ali Murad of his father’s death,” explains Mir Mehdi, “he avoided staying there altogether.” Instead, he would pitch tent in a garden called ‘Dobagh,’ on the outskirts of the town.

Langley, it appears, did not have an eye for detail. Limited perhaps by cultural differences, he fails to elaborate on the appearance of the tents, and insinuates that living in them demonstrated a lack of civilisation. Marianne Young, wife of Captain Thomas Postans of the Bombay Army, on the other hand, displays a more acute sense of observation. In her May 1843 article for The Illuminated Magazine, a monthly publication based out of London, Young describes Mir Ali Murad’s tent as being “made wholly of bright crimson cloth, richly embroidered, and surrounded with an outer wall, to keep off the people. The interior,” she continues, “was decorated with hanging lamps, rich Persian carpets, and large cushions of purple velvet, worked with seed pearls and gold, while the entrances were sentinelled with a body guard, dressed in a uniform similar to that worn by the soldiers of the Punjab.” She adds that “Of all the princes of Sindh… I was most charmed by Meer Ali Moorad of Khyrpoor, who is the very beau-ideal of a strong-hearted and independent chief.”

The custom of living in tents was not primitive, but served a practical purpose. It enabled the Mirs to remain in a constant state of transience, which best suited their passion for sport. Being land-owning barons, it also allowed them the mobility to inspect their territories and subjects. There would be little inconvenience or fatigue, since their ‘home’ would move with them wherever they went. At the same time, constantly being on the move provided security. An enemy could not plan a strike, since it would have been hard to predict where the Rais would decamp to next. Langley reports that Mir Ali Murad “will never allow his people to know where he means to halt for breakfast, and his intending sleeping place is even kept a more profound secret.”

Langley again generalises when he says that “The entire household furniture of Khyrpoor can be comprised in a single word, ‘the charpoy’… for neither table nor chair does His Highness possess.” Young, in her article, describes the “magnificent posts of a charpoy, or native bedstead,” being “encrusted with precious stones, emeralds and rubies; the value of each… estimated at two hundred guineas.”

Since only women and children lived indoors, the oldest known zenana of the Mirs of Upper Sindh is located inside the fort of Kot Diji, built in the 1780s by Mir Sohrab. The zenana’s ceiling was, according to Mir Mehdi, once inlaid with decorative mirror work, which served the function of multiplying/reflecting the light of candles and lanterns at nighttime. From 1811 onwards, it was here that Mir Sohrab spent the latter part of his career – in a tent outside the zenana – watching Mir Ali Murad I grow up. By the 1850s, the zenana had already moved outside the walls of the fort, and into the village of Kot Diji.

Like families, bungalows and fortresses too have generations. The first generation of monuments of the Mirs, described in detail in nineteenth century memoirs of various British visitors, were made when the family first established its foothold in Upper Sindh. Other than the fort at Kot Diji, none of these remain. The second generation of bungalows and autaqs (halls of audience) came up in the 1890s, during the reign of Mir Faiz Mohammad I. It is these that can be seen today in Kot Diji and Khairpur. Like their predecessors, they were used to receive and entertain important guests. According to Mir Mehdi, Mir Faiz Mohammad’s advisors and viziers emphasised the need for impressive-looking darbars as tokens of sophistication and stature, where British officials could be hosted. And so, they were erected, explains Mir Mehdi, “to keep up with the Joneses.” Architect Arif Hasan points out, “They were made at a particular time, when there was a merger of the European revival styles and local classic Indo-Islamic architecture.” Thus, he says, they are a mélange of many styles.

In the late 19th century, an increasing number of halls of audience, based on a common prototype, could be seen on the estates of Sindh’s nobility. According to Dr Anila Naeem, Co-Chairperson of the Department of Architecture and Planning at NED University, “Colonial-vernacular hybrid architecture became a symbol of wealth, power and prestige. Hence we see examples of it all over the region, commissioned by the nobility and later by the upcoming class of zamindars or waderas.” Over generations, some of the darbars were transformed into living quarters. A number of these ancestral properties survive across the province.

According to Mir Mehdi, the sizzling temperatures in Sindh did not permit structures as elaborate and palatial as those found in princely states. While the layout was kept relatively simple, the focus of the design was to enable an effective cooling system and airflow. This is why the Mirs’ bungalows are surrounded on all four sides by arched verandas up to 12 feet wide. The thick, brick-and-lime-mortar walls keep out the heat in summer and the cold in winter. The diwan-e-aam, or the hall of audience, lies at the very centre of the structure, its ceiling significantly higher than the rest of the bungalow. At the very top of its four walls are windows (badwaan), through which hot air escapes the building. The latticework covering the verandas is lined with mats made of khus-khus leaves, which, if sprinkled with water from the outside, have a cooling effect on the air that flows through them.

Mir Mehdi’s grandmother, who witnessed the transition from this old-fashioned system of cooling to that of the air conditioner, never felt comfortable in the recycled air of the latter. But even as early as the 1850s, there already existed in the subcontinent, a precursor to the air conditioner, in the form of the thermantidote. This was a box about the size of an oven, containing a built-in hand-operated fan and windows on all sides that were lined with moist khus-khus. Langley saw one of these inside Mir Ali Murad’s darbar in Kot Diji.

Takkar Bungalow (‘House on the Hill’), in Kot Diji, was built to accommodate the guests of Mir Faiz Mohammad I. Located at the top of a steep butte, this impressive mehman khana (guest house) remains closed to the public as it is the current home of Mir Ali Murad II and his family, who occupy it when they visit their ancestral village. At all other times it remains locked. The narrow road that leads to it winds along the edge of a cliff and culminates at the bungalow’s old gate. The canon outside this gate was, according to Mir Mehdi, bought from Queen Victoria’s grandfather, King George III, whose initials it bears.

Takkar Bungalow was built in the Anglo-oriental style common in the 1890s. Its circular-shaped bedrooms are located at the four corners of the house, their walls surrounded by windows, to enable a maximum flow of air through linings of khus-khus. Some of these windows were later closed off and turned into wall closets (darri) and shelves. The rooms have been fitted with false ceilings – the original ceiling being too high to allow effective air conditioning. The latticework of the verandas has been replaced with meshes, to keep out mosquitoes. At some point in its lifetime, the bungalow caught fire and had to be repainted in the original style. “The new paint job is not a good one,” laments Mir Mehdi. Parts of the structure, one bedroom in particular, have been reinforced with concrete blocks, which take away from its aesthetic appeal. The mansion faces south, overlooking a two-level courtyard on the edge of a cliff. It was in this courtyard that Mir Faiz Mohammad pitched his tent, while his guests slept inside the house. On its lower level is a small, unkempt garden. The courtyard affords panoramic views from west to east. Mir Mehdi explains that a forest bordered the southern side of the hill up until the 1950s and black buck could be spotted around the peripheries of Kot Diji. Takkar Bungalow is unique in that its interior does not have an uplifting atmosphere like those of the other bungalows. Instead, a ghoulish sense of heaviness prevails. Mir Mehdi refers to it as a “house of horrors.”

The exterior of Suffaid Mahal, or ‘The White Palace,’ built as a darbar in the 1890s by Mir Faiz Mohammad I, displays a strong influence of nineteenth century Sikh architecture – its arches in particular. It is still used as an autaqby its current proprietor, Mir Ahmed Talpur, a cousin of Mir Mehdi. His family resides in the old zenana opposite Suffaid Mahal. The ceiling of Suffaid Mahal’s diwan-e-aam is, like that of most others, lined with wood and contains mirror work and floral patterns. According to Dr Naeem, this style of interiors exhibit a Persian influence that was also employed in Mughal architecture. Suffaid Mahal’s frescoed walls, however, have been retouched. And it is furnished with an antique swing and cabinets. Among the numerous old photos and portraits that hang on its walls are, an original lithograph of Alexandra of Denmark who was Princess of Wales from 1863 to 1901, and a photo of Lady Curzon.

“The protruding balcony, or jharoka, on the first floor,” explains Dr Naeem, “is a typical feature in the palaces and havelis of Rajasthan. Since this particular one faces towards the open grounds within the boundary of the bungalow, it is quite possible that it may have been used for ceremonial purposes by the royals, for public sightings, as was the tradition among the Mughals, and British royalty as well.” The Endowment Fund Trust (EFT) is currently repairing the pillars of Suffaid Mahal’s veranda. “We are using bricks from Rahim Yar Khan,” explains Hamid Akhund, secretary of the EFT, “as these are of the required thickness and are made of earth that doesn’t contain salts.” EFT is also in the process of rebuilding a boundary wall around Suffaid Mahal.

In the 1890s, Mir Faiz Mohammad’s son, Mir Imam Bux, hired a French nanny for his firstborn, Mir Ali Nawaz. The house built for her became known as Mandam Waro Bungalow, or Madame’s Bungalow. This home of Mademoiselle de Flo is one of Kot Diji’s best-kept secrets. It exudes a quaint and understated charm, owing to its smaller scale. Yet its exterior displays, arguably, the most intricate carvings and stucco work of all the bungalows in Kot Diji. Dr Naeem describes it as being “less Anglo and more oriental.” She says it is possible that the other bungalows too had carvings as intricate, and that they may have been spoiled due to alterations in the name of ‘renovations.’

Two opposite ends of this symmetrical redbrick structure open up into entrances while the remaining two ends have latticed verandas. Dr Naeem explains that deep verandas were a traditional feature of bungalows in Sindh, as they provided shade from the tropical sun and at the same time allowed the provision to enjoy the outdoors. The roof of Madame’s Bungalow is furnished with a small pavilion where Mademoiselle de Flo undoubtedly spent many a summer night. Geo-climatic conditions in the plains necessitated an architectural layout that, in light of the large retinue of domestics employed, would have allowed minimal privacy. Mir Mehdi recalls little or no privacy in the time he spent in Takkar Bungalow as a child. Dr Naeem points out, “the notion of privacy would have been very different for the people of those times and places than what we perceive in our urban context.”

In the end, it all proved worthwhile; Mir Ali Nawaz, reared by a French nanny, went on to attend Aitchison College, followed by the Imperial Cadet Corps in Dehra Dun. In 1921, he was inducted in the Chamber of Princes, in Delhi. Madame’s Bungalow, now empty and neglected, is in a state of disrepair and has not seen any conservation work. Mohan Lal Ochani, Project Director at the EFT, says that the main problem afflicting heritage sites across the province is that of rising dampness. “There are several methods of dealing with this,” he explains. “We can either inject the structure with synthetic material that prevents salinity from affecting the paint (also known as damp proofing), or,” he continues, “we can use the Aquapol system.” This groundbreaking new method, invented in Austria, involves the installation of an antenna-like device in the ceiling of a building. The device uses wireless technology to dehydrate the walls above and below ground level. It has a coverage area of 500 square metres and costs Rs. 1,595,000.

Also in a state of decay is Shahi Mahal, the court of Mir Faiz Mohammad I, constructed in the 1890s. It stands to the northeast of Kot Diji, adjoining the nearby village of Abad. Unlike the other bungalows, which are located inside Kot Diji, Shahi Mahal is surrounded by agricultural fields and as such, has a pastoral feel. It remained a court until the 1920s, when, under the reign of Mir Ali Nawaz, Khairpur State adopted the British legal system. The frescoes on its interior are more detailed than any other in the current bungalows of the Mirs of Khairpur. And unlike any of the other bungalows, the ceiling of its main hall is arched. The exterior has, on three sides, porticos varying in detail and design, which serve as main entrances for the public. On the fourth side, which is the back of the building, is a columned veranda, at the corner of which lies a segregated entrance for women: a stairwell leading to the upper level. This stairwell has crumbled and all that remains of it is a pile of bricks. Referring to the smaller rooms/wings that surround the main hall of audience, Dr Naeem explains that these were either used for “private meetings and conversations that could not be carried out in the main public hall,” or as “resting chambers by the royalty.”

A similar concept applies to the layout of Faiz Mahal, Mir Faiz Mohammad I’s court in the town of Khairpur, also built in the 1890s. “Its east wing,” explains Mir Mehdi, “consists of royal chambers, for the sovereign to prepare for royal ceremonies, as well as six waiting rooms.” The west wing, on the other hand, comprises eight waiting rooms for high-ranking courtiers, nobility and visiting foreign dignitaries. “On the first floor,” he continues, “are two corridors overlooking the darbar from either side, from where the zenana would watch the proceedings. The central tower contains two rooms, which were formerly the library and billiard room.” On the second floor, at the top of the central tower, lies a room that provides views of the garden and city. In the hall of audience, a photo of the wedding ceremony of Mir Faiz Mohammed II in 1932, shows the Nizam of Hyderabad (the bride’s cousin) in attendance, accompanied by his two famous daughters-in-law – Princess Durr-e-Shehvar (daughter of Abdul Hamid Khan, Turkey’s last Ottoman Emperor), and her cousin Princess Niloufer, who would, in the course of that decade, be renowned internationally for her beauty.

Behind Faiz Mahal lies Dilkusha Manzil, once a zenana, but now used by the Deputy Commissioner of Khairpur as his office. In the vicinity of the Mahal is the Summer Laandhi, a guest house where, according to Mir Mehdi, Lord Kitchener briefly encamped at some point during his tenure as commander-in-chief of the Indian Army, between 1902 and 1911. An orchard near Faiz Mahal housed a prison in the days of the Khairpur State. “Prisoners used to assist palace staff and gardeners until the system was modernised and the jail was turned into a technical training institute for convicts,” says Mir Mehdi. “The products that were made included blankets, which were sold to the military, and other items of basic need. The income from the sale of these was divided into two equal portions. One was provided to the families of the convicts as a means of support, while the other half was collected and handed to the prisoner upon release.”

Mir Ali Murad II, Mir Mehdi’s father, currently resides in Faiz Mahal. He ascended to the throne in July 1947, shortly before Partition, at the age of 14, after which he attended Cambridge University. “The decision of whether to remain independent or join India or Pakistan was a burden thrust upon him at a young age,” explains Mir Mehdi. “There was immense pressure on the family, from the British, to join Pakistan, as they felt it would be beneficial for us.”

The family tradition of living in tents had faded away by the 1930s, during the reign of Mir Faiz Mohammad II, who, having attended Mayo College in Ajmer, followed by Oxford University, was more Anglicised than his predecessors. Mir Mehdi himself attended the State University of New York (SUNY), from where he was suddenly called to the front lines in 1995 to help deal with a territorial dispute. The husband of the then sitting prime minister, had made attempts to purchase Khairpur House in Karachi as well as the one in Lahore, explains Mir Ahmed. “He went so far as to threaten to forcefully occupy these properties. But instead,” laughs Mir Ahmed, “the only thing he occupied was a prison cell, after his wife’s government fell.”

The residents of the village of Kot Diji are predominantly Jaths, Khashkelis, Chandios, Lasharis and Gopangs. Some of them are descendants of individuals who had been in the service of the Mirs over a century ago, as accountants or munshis. “Some people work in banks, while others run dhabbas,” says Mir Ahmed, “but there is still a lot of unemployment. And there are power outages for 12 to 18 hours everyday.” He explains that the flour mills that have been put up outside Kot Diji have provided some locals with work. Gopangs tend to be peasant farmers and Jaths have taken up jobs at stone-crushing plants set up by Sachal Engineering Works (Pvt) Ltd. Pointing to the limestone buttes around the southern and western peripheries of Kot Diji, Mir Ahmed explains that these, along with others in the Mehrano and Nara regions, had been leased out by the Mirs to the Frontier Works Organisation as quarries.

Sher Khan Rajput, a labourer, makes his way home in the long shadow of the fort at the close of day. Although his children are educated, he says that the Mirs are his family’s only hope and guiding light. While Mir Mehdi maintains a distance from politics, his cousin, Mir Shahnawaz Talpur (also known as Mir Shaanar) made his political debut in the 2013 general elections. “Both Mir Mehdi and Mir Shaanar are honest men who treat their people in a respectful and just manner,” reflects Rajput. “This is all that matters to me.”

0 notes

Text

The Karachi Theosophical Society

Feature published in Newsline.

The chaos of Karachi’s MA Jinnah Road is muted inside the library at Jamshed Memorial Hall – a nostalgic byword for Karachi’s generations past. Leather-bound volumes of the first edition of Helena Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine line the shelves. This is the home of the Karachi Theosophical Society, a relic of a more enlightened period in the decaying city’s lifeline.

The Society’s genesis in Pakistan lies in inspirational lectures delivered by Annie Besant, a leader of the Indian Independence Movement and one of theosophy’s most influential figures, in Karachi in 1896 and Hyderabad, Sindh, in 1901.

Universal brotherhood is a central tenet of the Theosophical Society — as is scientific, philosophical and mystical inquiry, open to all religions and bound by none. Theosophists believe an ancient wisdom underlies all creeds. They seek to access a higher spiritual plane, through meditation, intuition and the study of theosophical literature.

“We are all renegades here,” says Hamid Mayet, General Secretary of the Karachi Theosophical Society and President of the Theosophical Order of Service, Pakistan. Having defied social norms and challenged the status quo for much of his life, Mayet is the best man for the job. Beneath his casual, easy-going demeanour lies a steely resolve. He moves across its corridors of Jamshed Memorial Hall with the air of a man who has broken free of the baggage of tradition.

Hailing from an affluent Indian family of Johannesburg, Mayet grew up in South Africa during Apartheid. “Within the Indian community itself – whether it was Hindus or Muslims – there was discrimination against blacks and a pronounced class inequality,” he recalls. “I found it all very hypocritical; attitudes seemed to contradict the religions that were so ardently being followed.”Inspired by anti-Apartheid leaders such as Dr Yusuf Dadoo, chairman of the South African Communist Party, Mayet started rebelling at a young age and became a conscientious objector. At the age of 16 he joined the youth wing of the Pan African National Congress. “In my heart of hearts, I was trying to identify with the common man,” he says. “I felt embarrassed that I was from a well-off family, when all around me there was racial and economic inequality.”In Pakistan, theosophists prefer to remain below the radar. The Karachi Theosophical Society’s website doesn’t give away any names. The fate of Dara Mirza, a former chapter president, is testimony to the darkness that engulfs the city. Mirza’s portrait hangs beside those of Blavatsky – co-founder of the Theosophical Society – and Jamshed Nusserwanjee, a former president of the Karachi chapter and the city’s first mayor. A descendant of Sindhi literary scholar Mirza Kaleech Baig, his ancestors migrated to Sindh from Georgia in the mid-nineteenth century. He was the president of the Society for over three decades, until September 14, 2007, when his body was found in Mauripur, Karachi. He had been kidnapped on the way to work earlier that day. The episode remains buried in a deafening silence.

“Dara Mirza, a learned man, had a strong grasp of esoteric philosophy,” says Mayet. The Esoteric school focuses on accessing the higher spiritual plane – described in theosophical texts as “the unexplained laws of nature and powers latent in man.” According to Mayet, the previous generation of members, such as Amir Ali Hoodbhoy and Hatim Alvi, carried out a deep study of theosophical literature. The current membership of 50, however, gravitates towards the Theosophical Order of Service (TOS) – a social services wing.

The ever-expanding Montessori at Jamshed Memorial Hall provides underprivileged students with a quality education at a fee of Rs 1,700 a month. Nusserwanjee and Minwalla felt that Italian educator Maria Montessori’s emphasis on creative and independent thinking had much in common with the values of theosophy.

The theosophists of Karachi are currently working towards opening a Montessori at the Besant Lodge in Hyderabad – a structure that Mayet describes as being “far more impressive than ours.” After the demise of the Lodge’s president – the renowned scholar and political activist Ibrahim Joyo in 2017 – membership has dwindled. A member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement, Joyo’s controversial work Save Sindh, Save the Continent – From Feudal Lords, Capitalists and their Communalism, published in 1947, resulted in the termination of his teaching post at the Sindh Madressa. Joyo was not the only theosophist to find himself at odds with the Madressa. A few decades earlier, Hatim Alvi, a student at the institution, was expelled for writing an article critical of the British rule.

“The Theosophical Society attracts people who tend to think out of the box,” says Mayet. “It has nothing to do with political orientation. Nor are we a religious organisation. This is a society that promotes unity.” He says it was Joyo’s interest in Sufi culture that made him gravitate towards theosophy. “Sufism is closer to esoteric philosophy.”

“If you want to find God, you can find him in the garden,” says Mushtaq Jindani, Joint Secretary of the Karachi Theosophical Society and Director Education, TOS. “You can cultivate God in the garden.” Jindani heads a small club called The Linkers, a group of people interested in mind sciences – the kind that deal with spirituality in relation to the mind and body.

Mayet is doing his best to make the Karachi chapter sustainable, so that he can hand it over to the next generation in working condition. “It has existed for over a hundred years, and I want it to be there for another hundred,” he says.

Theosophists of Hollywood

Of Hungarian descent and a Gnostic bishop, he is an author and incumbent President of Besant Lodge in Los Angeles. The name is Stephan – pronounced Stephaan – Hoeller. The eyes, half-closed, look neither up nor down, but see everything. And despite his advanced years, the bearing is sturdy. He holds his cup of coffee at a tilt. This may look like a mannerism, but it may also be because his grip is not quite firm. Tellingly, the initials ‘S.H.’ are embroidered on the cuffs of his crisp shirt.

Stephan hands Winter Lazerus, fellow theosophist and property manager at Besant Lodge, a letter he received in the post. “God knows what it means,” he says, amused by its cryptic content. Lazerus proceeds to examine the note and its accompanying talisman – an aboriginal woman holding a wand.

I pray you understand. I can only hope to sit with you again over eggs and beacon. The time is now.

1. Fix a tall drink,

2. Listen to the next song,

3. Remember,

4. The gift is yours so tear it open.

Love,

H E S

On an enclosed page torn out of a dictionary, the word ‘wizard’ is underlined.

Lazerus, clad in all black and sporting a pony-tail, cuts a tall, shadowy figure. He lives in an old cottage behind Besant Lodge. This is the quaint and leafy neighbourhood of Beachwood Canyon. It is the home of Stephan, Lazerus and the Theosophical Society. It is also home to the sprawling Hollywood sign – an intruder in this quiet part of Los Angeles. But the Society predates Hollywood – cinema was a comparative latecomer in these parts.

“The theosophists came to these hills because they believed that the spiritual and creative energy was strong here,” explains Stephan. And so in 1912, Albert Warrington and his associates founded the hamlet of Krotona – the society’s first national headquarters. The colony, located up the hill from Besant Lodge’s current location, is a collection of Moorish structures that have been converted into apartments. “Dora van Gelder Kunz, a former president of the Society, writer and famous clairvoyant, also believed that there was an angelic energy present in this particular part of Southern California,” continues Stephan.

The Lodge’s stained glass windows give its interior a church-like quality. They display the celestial symbols illustrated in theosophical teacher Geoffrey Hodson’s The Kingdom of the Gods. “Many think that this building was part of the old colony of Krotona,” says Stephan, “but that is not the case.” It was in fact a neighbourhood movie theatre, built in the early 1920s. “The first silent film theatre in Los Angeles,” Lazerus proudly adds. His cottage, even older, was once a bookshop. The Society bought both properties in 1954, while Stephan was on the board of directors.

This easternmost tail of the Santa Monica Mountains has always lured theosophy into its fold. Although Krotona relocated to Ojai owing to financial difficulties during the Great Depression, the Society returned in the incarnation of a rented facility near Beachwood Canyon before acquiring its current location. The commune in Ojai, now the Krotona Institute of Theosophy, is a thriving centre of research and spiritual learning.

Unlike many residential areas of Los Angeles, “there is a sense of community here, in Beachwood Canyon,” says Lazerus, “a real sense of the old part of L.A.” To locals, Besant Lodge is a community centre of sorts. “The Los Angeles chapter has about 20 to 30 members,” says Stephan. It hosts lectures, classes, readings, joint activities with the Gnostic Church, and has “offered Spanish lessons for the last 20 years.”

Further west, in the winding lanes of Bel Air, lifeless mansions gaze coldly at passing cars. Beachwood Canyon, however, has a soul. A nameless canyon and remote farming community in the 1880s, it became the site for an ambitious yet short-lived housing project – Hollywoodland – in the 1920s. “We border the largest municipal wilderness preserve in the world, where mountain lions roam,” says Lazerus, referring to Griffith Park.

Stephan produces a rare photo of Annie Besant. She is about to board a Goliath airliner with Charles Blech, general secretary of the Theosophical Society in France, and an unnamed gentleman. On the Lodge’s wall hangs the charter of Krotona, bearing Besant’s signature. It is dated 1920 – the year she visited the colony, as the Society’s international president.

Stephan, an aristocrat, struggled against oppression in his early years. When a Soviet-style communist regime consolidated power after the Second World War, his family lost all their property and lived in great need. He left Hungary, arriving in the US in 1952. “The Nazis had destroyed a lot of theosophist literature during the war, and subsequently, so did the communists,” says Stephan. “Totalitarian governments do not like organisations such as the Theosophical Society.” At first, Stephan dreamt of becoming a Catholic priest. And although he was 15 when he first heard of theosophy, it wasn’t until his arrival in Southern California that he joined the Society.

“Gool Minwalla was concerned that the Muslims’ suspicions of other religions would one day become a problem for their own countries,” says Stephan. “She was a fine lady,” he says of the former president of the Society, whom he had met in Ojai in the early ’80s. According to Stephan, it was during Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s tenure that religious intolerance first surfaced in Pakistan.

When Stephan first joined Besant Lodge 60 years ago, there were over 100 members. The current membership is only a fraction of this, owing to the existence of numerous other spiritual organisations. In what seems like a valedictory remark he emphasises the need to reconnect the “threads” that link theosophical societies across the globe.

0 notes

Text

Murder ink

Published in Newsline.

On November 2, 1896, Wadero Ghulam Murtaza Bhutto, grandfather of Pakistan’s former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, boarded the 7:35am train from Naudero to Larkana. The young wadero was a grandson of Doda Khan Bhutto, the largest landholder in the Upper Sindh Frontier district and among the most distinguished in the Shikarpur Collectorate.

Earlier that morning, and on the previous day, events had transpired that would alter the fate of Ghulam Murtaza and his immediate family. This included his minor son, Shahnawaz Bhutto, who would later be knighted.

Arriving in Larkana in 41 minutes, Murtaza, accompanied by his retainer Chuto Khashkeli, travelled onwards in a hired horse-and-carriage. Their destination was the town of Qambar in the Chandio heartland.

In the meantime, at 9:15am, the Collector of Shikarpur, Colonel Alfred Hercules Mayhew, received an urgent telegram from the tapedar in Naudero. It reported that Rao Jeramdas, the mukhtiarkar of Ratodero taluka, had “suddenly” died while encamped in Banguldero. About an hour and a half later, another urgent telegram followed. It specified that Jeramdas had been “killed.”

As Collector, Mayhew was the highest authority in Shikarpur district. This was an administrative unit that spanned a vast area (10,242 square miles) including what are now districts Qambar-Shahdadkot, Larkana, Shikarpur, Ghotki and Sukkur. Additionally, he had magisterial powers over the entire region.

Mayhew wasted no time in bringing the matter to the attention of Sir Henry Evan James, the Commissioner in Sindh. Mr Spence, the District Superintendent of Police wrote to Mayhew on November 9, 1896. His handwriting betrayed haste:

“From what has been found out as far as the enquiry has gone up to date, there can be no doubt that a great deal of money has been, is being and will be spent to try and prevent the real offenders and their instigators being brought to justice and without the offer of a large reward on the side of the Government, there is little or no hope of anything being brought to light.”

Spence proposed a sum of Rs 1,000 as a reward for information leading to the arrest of those complicit in the murder, which was “of a most brutal nature.” Mayhew seconded the proposal and the reward was sanctioned by the commissioner. The deceased’s father, Rao Dharamdas, a wealthy landowner and merchant based in Thatta, put up an additional sum of Rs 500 as a reward.

Based on evidence collected in the investigation, Wadero Ghulam Murtaza Bhutto was accused of instigating the murder of the mukhtiarkar – the highest authority in the taluka.

In his letters to the commissioner, Colonel Mayhew’s signature in red ink has the conclusiveness of a seal. He wrote on November 9, 1896:

“The accused Ghulam Murtaza Khudabux Bhutto is a wealthy and powerful man possessing enormous areas of land in this [Shikarpur] and the Upper Sind Frontier District…

The deceased R.S. [Rao Sahib] Jeramdas Dharamdas… has lost his life in the earnest, conscientious and determined performance of his duty in the public interests and in making efforts to bring the man Ghulam Murtaza Khudabux Bhutto to his senses and to make him mend his wicked and infamous and dissolute ways and to give up his evil practices which are dishonest and criminal – so has brought down upon him beyond question the wrath or revenge of this powerful rascal.”

On what grounds was the young wadero charged with perpetrating the murder?

An order issued by the Shikarpur Sessions Court Judge, Dayaram Gidumal, on November 20, 1896, provides a detailed account of the facts of the case. It includes sworn testimony from Pandhi Arzi and Hussain (members of Jeramdas’ staff), Salamatrai, a zamindar from Banguldero, Ali Sher, a small landholder who assisted the mukhtiarkar in his remission work, Abdul Fatah, the Chief Constable of Qambar and Wahid Bux, a commuter.

On the day prior to Jeramdas’ murder, Ghulam Murtaza had gone to see him in Naudero. The revenue officer was said to be preparing an official report against the wadero, whom he considered a “bad character.” Murtaza was made to wait outside in the sun for an hour. And when finally summoned, was only allowed a brief audience.

In nineteenth century Sindh, such treatment was an outright affront to the honour and prestige of a man of position. Vowing revenge, Murtaza repeatedly proclaimed, “This Diwan [government official] gives me no proper respect. I shall ‘see’ him [maa hin khe disee rahandus].”

In the late afternoon, as temperatures cooled, Jeramdas left Naudero for the village of Banguldero. The shortest route, even today, is through Garhi Khuda Bux. During the journey his entourage passed the red-bricked autaaq of Ghulam Murtaza Bhutto. Seated in the courtyard, the wadero pointed the mukhtiarkar out to a man sitting next to him.

The caravan arrived in Banguldero at 9:15pm and set up camp in the tapedar’s (field surveyor’s) dero. That night, for whatever reasons, the mukhtiarkar’s attendant, Pandhi, refused to accommodate Ali Sher, a member of the retinue. Searching for a place to stay in the late hours, Sher landed up at the autaaq of Zeno Drakhan, a resident of the village. Inside, he sat by a fire, adding straw to the burning cinders. As the flames grew, he saw in the room a face of a stranger. In the investigation three days later, Sher would identify this man, who was none other than Nuro, a hari of Khuda Bux Bhutto, Ghulam Murtaza’s father.

Turned away by Zeno too, Sher was forced to spend the night in a village a mile from Banguldero.

Jeramdas, meanwhile, fell asleep at midnight, while having his legs pressed by his peons. Salamatrai and the local munshi, who were with him until then, bid their leave. In the past, whenever the mukhtiarkar had put up in the village, he employed two roadside maalis (gardners) to keep watch on the camp at night. But on this occasion, interestingly, when the maalis turned up, Pandhi told them they weren’t needed.

Other than the cook and an attendant, the entire retinue slept outside the compound, the gate of which was chained from the outside.

The following morning, Jeramdas was scheduled to inspect Salamatrai’s crops. His attendant’s repeated attempts to wake him up by making a racket outside his room hadn’t worked. By 8:30am, Salamatrai ventured inside and lifted the blanket. He saw a face and beard drenched in blood.

In tears, members of the mukhtiarkar’s staff immediately proclaimed that Wadero Ghulam Murtaza was “the author of the murder as he had been dishonoured on the previous day.”

Earlier that morning, Wahid Bux, a commuter on the Garhi Khuda Bux-to-Banguldero road crossed paths with three men whom he knew, near the village of Kot Bhutto. They appeared to be coming from Banguldero. He would later identify them as Nuro – the man in Zeno’s autaaq, Chuto Khashkeli – Ghulam Murtaza’s retainer and Chuto Jagirani. He noticed Khashkeli was carrying a sword.

At 7:35am, Khashkeli and Wadero Ghulam Murtaza caught a train to Larkana. The two arrived at their final destination, Qambar, at 10am via Nabu’s horse and carriage. Here, Murtaza called on Abdul Fatah, the Chief Constable of Qambar.

He reported to Abdul Fatah that one of his mares had gone missing and the constable noted down a detailed description of the animal. Jeramdas happened to come up in the conversation. The constable inquired whether the mukhtiarkar of Ratodero had sent Colonel Mayhew the report he was preparing against Murtaza. Bhutto replied that the mukhtiarkar was dead.

In court later that month, the public prosecutor argued that Murtaza had made this journey so that he would have an alibi if accused.

On November 3, an interesting piece of evidence was unearthed in the investigation. A purse belonging to the mukhtiarkar, stolen on the night of his murder, was found in Khashkeli’s quarters in Ghulam Murtaza’s autaaq. After Murtaza’s arrest, two applications for bail made by his counsel, Mr Grey, were rejected – first by the sub-divisional magistrate of Larkana and then by the Shikarpur sessions judge. The latter, however, noted in his judgement that the evidence collected thus far was circumstantial and that cross-examination may render it worthless. The accused was eventually acquitted.

In her autobiography, Daughter of the East, Benazir Bhutto recalls the mythologised tale of her great-grandfather as told by her father. It suggested that Mayhew had a grudge against Murtaza, the basis of which was an affair the latter had with a British woman.

In Zulfi Bhutto of Pakistan, Stanley Wolpert, who consulted Sir Shahnawaz Bhutto’s unpublished memoirs, dismisses this as an “amended” version of the story told by Sir Shahnawaz (who was 11 years old when his father, Ghulam Murtaza, died). According to his version, the young wadero had stolen Mayhew’s Sindhi mistress.

Neither of these versions mentions that the wadero was accused of abetting the murder of Rao Jeramdas. Wolpert fleetingly cites “the Hindu… who was murdered,” as a mere afterthought – selectively quoting from Sir Shahnawaz’s memoirs. David Cheesman, who does refer to the details of the episode in his work, Landlord Power and Rural Indebtedness in Colonial Sindh, argues that Wolpert’s version is more plausible than Benazir’s.

A.W. Hughes, a civil service officer and cotton inspector in Sindh, writes in the 1876 Gazetteer of Sindh, that one of the most common crimes in Larkana division was “adultery – or rather, the enticing away of married women with a criminal intent.”

Yet from the details of the trial it emerges that Mayhew may not have been driven by a personal vendetta at all.

In a memorandum to the Governor of Bombay dated November 17, 1896, the commissioner in Sindh notes that “…the suspected person is well known to have instigated other murderous attacks if not murders.” This would partly explain the mukhtiarkar’s attitude towards Murtaza when he paid him a visit, as well as the report he was preparing against the wadero. The memorandum also notes that Jeramdas’ murder “has terrorised all the officials around…” Additionally, it was Mr Spence, the Superintendent of Police, who pressed for the hefty reward.

A closer look at the career of Alfred Mayhew reveals a penchant for fighting injustice. Investigative journalist Mick Hamer, in his book A Most Deliberate Swindle, quotes Mayhew:

“I served 27 years in India, which I found to be a pretty bad place… But when I returned to London I found it to be a sink of inequity – and I determined to do all I could to expose… the rascals who rob the widow and the orphan.”

According to the India Office List 1893, Mayhew, during his 40-year-stint in India, served as the deputy commissioner of the Upper Sindh Frontier district, political agent in Khairpur State, acting political superintendent in Thar and Parkar and as a soldier in the Madras Army, prior to becoming collector of Shikarpur district. Among locals he had a reputation for being a fair official who interacted closely with serfs, labourers and sheperds to inquire about their problems, according to Pir Ali Muhammad Rashidi’s biographical encyclopedia, Uhay Deehan Uhay Sheehan. Rashidi credits Mayhew with playing an important role in the development of Sukkur as the economic centre of Upper Sindh.

The likelihood of a Sindhi – or any – mistress being at the centre of the episode also comes into question. As Collector, Mayhew was stationed in Sukkur. If he had a mistress, she would have most likely lived in the same city. Ghulam Murtaza, meanwhile, lived in a different taluka – a significant distance away even by train.

In Sir Shahnawaz’s version of events, Murtaza got into a physical altercation with Mayhew during which the colonel went and hid under a table. This would have been highly uncharacteristic of a trained soldier who had served in the Madras army and who at the time of the alleged confrontation would have been in his early-to-mid fifties (Mayhew died in 1913, aged 70).

David Cheesman points out that there were “sound political reasons for Mayhew’s alarm over Ghulam Murtaza’s acquittal.” Even if the possibility of a vendetta over a woman is ruled out, Mayhew had enough cause for concern. The acquittal had set a dangerous precedent. The administration appeared weak and ineffectual in the face of the immense influence wielded by the wadero.

There is nothing in the official record about what happened next. All we have is Wolpert’s version, based on Sir Shahnawaz’s memoir, according to which, at some point – possibly after being granted bail – Ghulam Murtaza went into exile, while the colonel had his home annihilated. His father, Khuda Bux, died after being “ambushed,” and when Murtaza returned to Garhi Khuda Bux in 1899 after being acquitted, he died of poisoning.

Colonial Blue Books maintained by British officials in Sindh contained confidential notes on members of the landed gentry in every district. The Blue Book of the Shikarpur Collectorate, which would have covered the years 1843 to 1900, is missing from the Sindh Archives. The Blue Book of Larkana district, which starts from 1901 – the year the district was carved out – is available, but many early entries, between 1901 and 1926 seem to have been omitted. A copy of the same book at the Sindhology Institute in Jamshoro contains entries that are missing in the Karachi copy.

Other than the record of the Judicial Department and correspondence between British officials, all of which revolves around Jeramdas’ murder, there is little or no information on Ghulam Murtaza. A glimpse into his family background, however, can prove instructive.

Doda Khan Bhutto, Murtaza’s grandfather and the family patriarch, died in 1893, according to the date on his gravestone. This was three years prior to the Jeramdas episode. Doda Khan’s home was in Village Pir Bux Bhutto, where he is buried. He lived there with his sons, Ameer Bux, Khuda Bux (Murtaza’s father) and Illahi Bux. All of them are buried in the old family tomb – except for Khuda Bux.

At some point, for reasons unknown, Khuda Bux moved out of Village Pir Bux Bhutto and settled in Garhi Khuda Bux. In nineteenth century Sindhi society it was not common for a zamindar to shift out of the ancestral haveli – unless he had a very good reason.

Stories passed down through generations within the family hint at domestic disputes, but there is no evidence to back this claim. What is certain, however, is that the breakaway was a permanent one, since neither Khuda Bux, nor his offspring were buried with the rest of the family.

The records of the Revenue Department provide interesting clues. A notice dated August 27, 1887 from C.B. Pritchard, the Acting Commissioner in Sindh, reveals that Khuda Bux’s share of landholdings was significantly smaller in size than other members of his family, including his brothers. While Doda Khan and his son Ameer Bux each had land spread across 25 dehs, Khuda Bux only had land in 15 dehs. Age had little to do with it, since the youngest brother, Illahi Bux, inherited the largest share under the last will and testament of Doda Khan. In other words, the sibling that moved away received the smallest share of the property.

This is particularly consequential in a society where a zamindar’s prestige and place in the social hierarchy is largely determined by his wealth. Ghulam Murtaza, therefore, was a member of a cadet branch of Doda Khan’s family. One that was comparatively less affluent. Was his fragile ego in part a result of this? Did Murtaza feel the need to go the extra mile to restore his honour?

It isn’t difficult to picture the crowd that would have gathered as the wadero waited in the sun outside Jeramdas’ office for an hour. Even today in rural Sindh, locals congregate in large numbers to catch a glimpse of notables in public spaces. And evidence suggests that there were witnesses. All eyes would have been on the scion – staring, judging, watching his every move. As Cheesman puts it, “Izzat was vital for the survival of any wadero.”

After Ghulam Murtaza’s death, Mr Mules, the new Collector, became Shahnawaz’s guardian, according to Wolpert. One of his primary aims would have been to cultivate in the eleven-year-old a cooperative attitude towards the administration. “I can’t see any other reason for putting him under the guardianship of a British Collector,” says David Cheesman. “It would be very similar to the way the British often cultivated the sons of nobles in the Princely States.” Cheesman recalls the correspondence of the Education Department in regards to some of the young Talpurs, “preparing them to rule with a British view of the world.”

This may help explain a lot about the later development of Sir Shahnawaz. In 1930, the deputy collector of Larkana described him as “loyal, very level-head” and having “no swollen head.” According to Cheesman, given the British relationship with Ghulam Murtaza, a collector’s first instinct would have been to avoid getting involved with a troublesome family. However, “there must have been something that made him feel Shahnawaz was worth investing in,” he adds. “Mules must have seen some spark in the young man which caught his attention and made him think he had potential.”

0 notes

Text

Chinatown

Cover story published in Newsline.

From the outside, the home of Wang Zheng Ru is like any other bungalow in DHA, Karachi. A high-columned, white structure that borrows eclectically from a variety of styles as well as making up its own. It would be best described as a house that was built in the eighties, when this part of Defence was associated with a newness that has long since moved several miles down the road to Phase VIII. As such, it now has a worn feel. But my appreciation of the house is disrupted by a contingent of Rangers who suddenly emerge from its gate and mount two Daihatsu pick-ups, the same colour as their uniform. Still seated in my car, I avert my gaze and pretend to stare into my phone, trying not to look suspicious.

After the two vehicles are a safe distance away from the house, and after I ask the designated doorman (who happens to be a policeman) if I should come back another day, he reassures me that that was just the census team.

Moments later, I am received by Zhai Yizhong, or ‘Joey’ as he is known to his friends. Having read my brief introductory note explaining the reasons for my visit, Joey has apparently approved my entry into Zheng Ru’s house, which I learn is also used as a guesthouse for Chinese citizens posted in Pakistan, of which Joey is one. This explains the utilitarian untidiness of the interior, which, despite its cosiness, abides by a set of patterns and laws that set it apart from most urban living spaces in Pakistan. If one did not know that foreigners occupied the home, one could perhaps think it to be a semi-public space, or a house used by an organisation, but even then, its undeniably alien quality would lead the more discerning to recognise a foreign connection.

Thirty-three-year-old Joey hails from Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang province, and speaks fluent English. As we wait for Zheng Ru to return from work, Joey throws a few nuggets of Chinese wisdom my way: “The first step towards strengthening an economy is building roads.” He is not, however, affiliated with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), having been posted to Pakistan in 2015 on behalf of a textile chemical provider, a partner of Protégé Chemicals. Recalling his first impression of Lahore, he reflects, “it reminded me of the China that my parents describe as having existed 30 years ago.” Joey predicts that in about three decades, Karachi will be Pakistan’s Shanghai.

Zheng Ru, the patriarch and owner of the house, has lived in Pakistan since 1987 and is a relic of the pre-CPEC generation of Chinese professionals who paved the way for the younger lot that now occupies their homes. He is a man of a few words, which he doesn’t mince. “In 1987, Karachi was better than Bangkok, Beijing and Dubai, as far as living standards, transportation and communication were concerned,” recalls Ru. “But in the last 30 years it hasn’t made much progress, those three metropolises having overtaken it.” He recalls that while Karachi had cars in 1987, Beijing had mostly bicycles. “Perhaps it was terrorism that stunted infrastructure development in Pakistan, or perhaps it was political corruption. This country needs a very powerful leader — democracy has always been weak here. That is why I think army rule is better for Pakistan.”

Seated in the front yard, our conversation is punctuated by the passage of residents, including young mothers in their 30s, stylishly dressed in jeans and T-shirts, and a friendly five-year-old who chats to me with such conviction that I don’t have the heart to tell her I don’t speak Mandarin. In the corner of the front yard there is a rockery – a staple of the 1980s homes of Karachi, although I increasingly feel like I’m in China. Mrs Wang Zheng Ru, a woman of substance, who can be heard before she has even arrived, and who arrives wearing an exceptionally large sun hat, has the charm and the iron fist needed to run such a house.

According to Ru, there are many similarities between Chinese culture and that of the subcontinent. “In China too, people live with their parents, in large families.” A qualified civil engineer, Mr Ru was the China Beijing Corporation’s representative in Pakistan until last year, when he retired. He is currently working for the Shaanxi Foreign Economic Trade and Industrial Group (SFETIC), a stated-owned enterprise under the provincial government of Shaanxi, as an executive manager for the Fazaia Housing Scheme project, in Karachi. Fazaia, a project of the Pakistan Air Force, signed a project development and construction contract with the SFETIC, in July 2016.

“Living in Pakistan, you realise that it’s not as bad as the media portrays it to be. The people are very friendly,” says Ru, who has also lived in Rahim Yar Khan and Islamabad. He tells me that some of Joey’s friends visited Karachi in the late 1980s and stayed in this very guesthouse, and that it was based on their positive reviews that Joey decided to come here. Nevertheless, Ru always carries one security guard with him when he steps out. Joey too, has a personal security guard – a former army man who is also his driver, but with whom Joey has the relationship of a “friend”.

Yet the sinister realities of life in Pakistan inevitably muscle their way in. For not too far away, in another guest house, dwell younger Chinese nationals who have a slightly different tale to tell. The house, being newer, has a more homely feel and stacked on either side of its front door are cartons of mineral water, juice, soft drinks, Chinese printers and other electronic kitchen items manufactured in China. On top of these, an entitled pet rooster stands tall with the grace of an eagle. In the garden, a hen and baby chicks run around gleefully. Part of the garden is a junkyard, to which furniture, plumbing-parts and unused commodes are relegated. At its other end is a large marble table, surrounded by marble stools, where important discussions must take place. A pillow lying on the edge of the table lends a laid-back effect to the environment.

Immediately inside the front door is a home-based grocery store that sells household items from Chinese cigarettes and gum, to Chinese detergents. Dyrus Luo is visiting Karachi from Lahore, where he works at the branch office of Sany Heavy Industry, China’s largest manufacturer of construction equipment. Luo, who hails from South China’s mountainous province of Hunan, associates Lahore with “culture” and “humility” and Karachi with “energy” and “openness.” Contrary to popular opinion that people from China stick to each other, Luo is sociable and fluent in English. But he is unable to leave the house much. “We have been advised by the Pakistani government not to venture out of our homes as it is too dangerous,” he explains. “As a result, our gate is always closed and we don���t have much communication with locals. If I was married, I wouldn’t bring my family here due to the security issues.” His housemate Tony Jiang, however, does get around. “I like the beach and the cheap sea food,” says Jiang, who may look like a college student, but has in fact worked for RNS Logistics in Lahore for three years and is currently posted in Karachi.

Luo, having been in Pakistan barely three months, has noticed that, “the government seems to care more about the military and protecting the country, rather than the problems of the people living in it.” Sounding like a local, he says that outside the bubble of Clifton and Defence, there is extreme poverty, about which the government is not doing enough. Luo is used to unfamiliar environments, having been posted to different parts of the globe over the past six years.

Similar security concerns are shared by Ma Long Zhou Tin, or as he is known by his Muslim name, ‘Omar,’ an engineering supervisor at a CPEC-affiliated construction company operating in Port Qasim (which he requests not to be named). The guesthouse in Clifton, Karachi, in which he lives is not a single unit run by a family, but a series of independent units that share a compound, and which can be occupied by up to 20 Chinese nationals at any given time. Although Omar likes dining at Do Darya, he and others in the compound are not allowed to go out everyday and when they do, it is always under the cover of security. Yet this does not stop them from frequenting the neighbourhood park down the road, security guards in tow, where they can be spotted lazing around, or meditating, or reading books on botany while closely examining flora. And Omar can still use WeChat, an instant messaging and calling app developed by Tencent, China’s leading Internet service provider. “It’s better than Whatsapp,” he says. “Many Pakistanis are now using WeChat,” the total international users of which currently amount to 846 million. Omar and his housemates also have access to channels broadcast by China’s state television.

“Due to congestion and overpopulation, apartments in China aren’t very spacious,” explains Omar, who is from Lanzhou, the capital of the northwestern Chinese province of Gansu. “In Pakistan, on the other hand, the homes we live in are much larger,” he says. Prior to being posted to Pakistan in 2015, Omar was in Yangquan, Shanxi (not the same province as Shaanxi). When Omar was first offered a posting in Pakistan, he says he was a little bit scared because all he knew about the country was what he had seen of it on TV: bombings and terror. But the move provided a good career opportunity. And besides, he says, “most Chinese people I know like Pakistan, otherwise they would not be here. If we cannot bear the life here, there is nothing stopping us from leaving.”

According to Peng Simin, Editor-in-Chief of Huashang Weekly, a Chinese and English newspaper based out of Islamabad, there are currently at least 50,000 Chinese nationals living in Pakistan. And given the myriad ventures they are involved in, chances are this number will rise over the next few years.

Who’s Afraid of the Dragon?

While the Pakistani media remains highly sceptical of CPEC, locals at the grassroot level are enthusiastic about the surge in Chinese residents in Pakistan, whom they view as harbingers of development and stability in the face of local alternatives that have repeatedly failed. “In the last two years, I have noticed a marked increase in Chinese people in Karachi,” says Muhammad Ashraf, who has sold bed linen and curtains out of his shop in Khadda Market for 17 years. “It can only bode well for our country. The CPEC will bring about prosperity. And whether we like it or not, the Chinese, on the whole, seem to be much more humane than our own people.” Ashraf explains that the 25 Chinese clients that frequent his shop are all very kind and respectful. According to Ashraf, while many livelihoods currently suffer at the hands of loadshedding, the Chinese energy projects aim to end the power shortage and this will only result in increased profitability across the board. Some of Ashraf’s acquaintances have bought property in Gwadar for Rs. 3 to 4 million, which is cheaper than property in DHA, Karachi. Taxi driver Huzoor Bux too has a soft spot for his roster of regular Chinese clientele who are concentrated in a residential pocket of DHA Phase IV.

Local professionals, however, are less optimistic. Kashif Iqbal, a local coordinator for New Technologies, a Chinese company that has been operational in Pakistan for eight years and currently provides security equipment to CPEC projects, tells Newsline that the CPEC is, inevitably, designed to cater to the needs and interests of China. “There is need of a policy or rule that enables local vendors to benefit from CPEC projects as well,” suggests Iqbal. “Currently, the main benefactors are Chinese companies, who are the preferred choice of the Pakistan government as they provide lower cost services in CPEC projects compared to local organisations.” He is quick to add, however, that there is no denying that these Chinese companies are, technologically, far more advanced than local competitors.

Abdur Rehman Shah, a research associate at Islamabad’s Centre for Research and Security Studies, who is currently doing a PhD in International Relations at Jilin University, in China, also raises some concerns. While talking to Newsline, he warned that if the Pakistan government did not properly manage the increased influx of Chinese nationals and investors in Pakistan, it could lead to a rise in cases where Chinese nationals/workers/businessmen start neglecting or violating laws. “Above all, there can be economic costs,” explains Shah. “Local industries and, to some extent, labourers will have to bear the brunt of the increasing footprint of Chinese nationals in Pakistan.”

According to Shah, current indicators regarding Pakistan’s rising debt obligations towards China are grim. “The government is more focused upon launching projects rather than justifying them on the basis of economic feasibility,” he laments. “The very lack of transparency in CPEC deals compounds the problem. Unlike the US, World Bank and IMF, the Chinese fundings are not bound by the conditions of economic reforms.” Shah points out that China’s official narratives on the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) iniatives, as well as the CPEC, “are steeped in overly promising rhetoric.” Environmental considerations have also taken a backseat in CPEC projects. This, Shah reflects, is emblematic of China’s development model.

Commenting on the Pakistani media’s overly hawkish stance on CPEC, Dr Asad Zaman, Vice Chancellor of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics and a PhD in Economics from Stanford University, told Newsline that “the media can play a positive role by focusing on how we can best exploit the tremendous opportunities created by the CPEC, which may pass us by if we keep bickering, and fail to recognise them. Repeating baseless apprehensions creates an impression of a scare-mongering propaganda campaign launched by Indians, sworn enemies of the CPEC project.” According to Zaman, fears regarding the debt burden are grossly exaggerated. He argues that since the debt is being used to finance infrastructure projects, it is of a constructive nature and will bring about immediate benefits to the domestic economy, as well as having a short payback period.

Zaman further states that Joint Working Groups and Joint Vehicles are being encouraged between Chinese and Pakistani enterprises to safeguard and develop local industries. He points out that while a total of 2,065 Chinese workers are employed in CPEC projects in Pakistan, they are far outnumbered by the 8,523 Pakistani workers employed in the same projects. He adds that more than 50 per cent of the Chinese nationals that have entered Pakistan are categorised as temporary labour migrants who will return to China upon completion of the projects.