Text

(Title unknown to author) Piet Mondrian. See Mondrian de 1892 à 1914: Les chemins de l’abstraction, eds. Hans Janssen and Joop Joosten.

Excerpt from ___ Mtn. Journals

September 12

10.

The next morning I woke up scared. I prepared the coffee and made two nice fried eggs with hearty slices of buttered toast. I even sliced a peach and ate it with the rest of the food. My shoulder to the window, I looked out toward the table. I thought about my trip to Canada and was grateful I had it on the horizon. I could see the horizon from where I sat and Canada was on it. The toast was especially flavorful today, and I cut pieces of egg with my fork and placed them on the toast, taking small bites to make the eggs last. The air was cool through the small crack I left in the window and I thought of Montreal and the future seemed to be about ten feet in front of me—about where the sink stood beneath a rack of hanging pans. The future was a comfortable distance, the air was cool, and I was no longer scared as I’d been when I awoke and lingered in bed. I replayed the image of the future on the horizon and relished the sensations of the idea. The idea was clear and straightforward, and it lent itself to easy images of streets and air and the faces of buildings. To laughing and the light smiles of my friends.

Above the sink, in the rack of pans, I noticed a small pot with a tan-colored handle. I’ve used many of their pots, but I’m not sure I realized this one was hanging among them. The rack has a long rod of steel connecting the right brace to the left, and it runs parallel to the more substantial arm of metal that seems to serve as the primary bulk of the rack. I hadn’t noticed the metal rod either. Beyond, where it attached to the wall, I looked at the wooden panelling and began to see little holes and tiny nails deeply impressed in the wood, apparently by a pneumatic nail gun. On top of the refrigerator there are several cardboard boxes with unknown contents and a set of colorful plastic mixing bowls. I was surprised I hadn’t noticed these before. It was as if they were appearing.

When I first entered the house, I’d had a similar sensation. Each room seemed to be appearing, and yet I understood perfectly well that the rooms had been there before I arrived.

I could look across the room and simply take it in, running my eyes over the objects, or, I could identify them. (Without identifying them, it was difficult to say whether I’d seen them before. Is this true?) I continued passing my gaze over the kitchen area. There was a tall, free-standing cabinet painted the color of a lake on a map. It had a few cookbooks on its shelf, and some faded paper towel leaning against an earthenware carafe with a pink rim. There were doors at the bottom, each only a half foot wide with arched inlays, like stained glass in a church. The doors were closed. It was easy to keep seeing new things. There were several little amorphous mounds in the ceiling, and more nail holes. On the hanging lamp fixture above the table, there is a single golden screw in a threading; it’s set in the center-right of the circular metal half-dome. I see the fake flower hanging from the handle of the refrigerator and I know it well.

..

The foundation of the house is made of many concrete blocks; two rows are visible along the bottom if not hidden by grass or cultivated plants. They appear as if always damp, even on the hottest day I saw in September. The higher row of blocks meets the wooden siding of the house—the boards are elegant and thick; a rough cut, only passively sanded, coated in a white paint that seems somewhat green. A few shrubs with particular force seem to clothe the siding with their glow, or with association. It is only association. The leaves don’t have enough true reflectivity, not like the moon, to put any green on the siding.

The blocks appear moist and I act as if I’ve touched them. I haven’t—I haven’t been within five feet of them, except where I enter the door. I never cross into the buffer of plants and mulch that beds them. I scratch my fingers along the concrete, or I raw my fingers on it—but this is mental. I do not touch it. I do not even know if it is wet. On the bare, well-lit side of the house, the long wall with the gas meter, the blocks are white like the windows. Even these seem like the walls of a well. I try to imagine dry concrete, hot concrete, and I can’t. The house is cool, as an object. There are probably days in deep summer when it becomes unbearably hot. But I imagine it as humid; this house is old and if I perceive the idea of an old house, it is damp—accumulated wetness.

I walk up and touch the dry block. September has been nearly summer, but never hot. I remember it as if a tepid wind had blow through it all, billowing dry brown grass and definitively expelling green. The sky is still and the highest clouds drift a bit as of their own volition. The sky is a gradient so subtle that it is confusing—white never ceases to be blue, blue is never empty of white. From the table in the kitchen, it is now midday and I have noticeably forgotten how I got to this hour. I do not notice the doorknob until I am standing in the yard, the unrelenting but unpainful daylight covering my body. The door clacks shut once more in auditory memory. And again, and I hear the bolt enter the door frame. I hear my feet shift the gravel; I take off my shoes at the porch platform and walk back barefoot; I curl the balls of my feet into the gravel and press hard into the arches to feel the rocks. It’s difficult to pace around on the gravel, but I do this as I think. It is not clear that I am thinking.

8/24/20

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Painting _____ Mountain’

9.

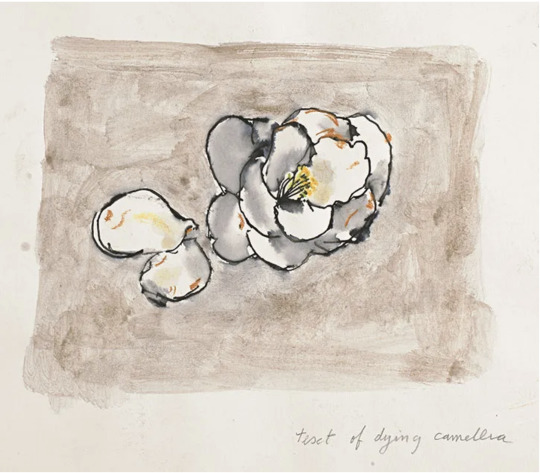

Text of Dying Camellia. John Berger, from ‘Confabulations’.

I wander around in the lane of the dismantled chicken coop, noticing an accumulation of age over the bare spots the chickens scratched open. I fix my eyes on the brush-pile and see the last fade of green in a few dry pine boughs. Four or five hens are running full-tilt toward the coop, clattering up the ramp with loud clacks and hard claws against the stiff wood. There is no echo here—the yard is too soft, too lush, and it absorbs all violent sound. Even a forceful yell would be absorbed into the earth. This does not mean there is any less sensitivity in the viewer of the yard, however. The sensitivity in this place is not a grating alertness, but an alertness that invites, anticipates, and desires sounds, turns of light, and movement. Perhaps this is trust, more than anything.

In the yard, I am less sure where I end. I feel more certain that the objects of my perception are myself. I am more certain that there is no particular world. To see the bush overflowing the fence is to see it in one inimitable way. The sparrow that constantly frets around inside the mess of pagoda-like stems sees it as the sparrow, and neither of us gets to participate in a definitive story of the world. The sparrow I see is unique to my life; and my appearance, too, is uniquely the sparrow’s. But their story of me is equal in magnitude to my own experience of myself; it is simply more brief. I was ready to feel this when I arrived.

I’m running laundry in the house and I hear its consistent buzz somewhere exterior to my thoughts. There is no sparrow, and the fence I see seems more the fence as I remember it, specifically as I construct it in the company of sparrows. Sometimes ten or twelve of them will chase themselves around the shrub, bursting from the tangle of vines and quickly entering again as if by elastic, one pressing its beak into the space of another’s ear. I want to return to the fence. In the yard, if I am attentive, I can be as if wind, as transparent and as altered by subtleties. I am trying to look at the fence immediately. So that the fence passes through me. What would this mean? A sparrow eventually does arrive, a missing fleck in the blot of the sun, and drops to the ground. As I stare at it, the gravel becomes more and more saturated until it is a brilliant shifting imprint-memory on my eyes. I look away. If the fence is who I am, what would it mean for it to pass through me? I cannot and do not want to give up my eyes. They are the shrub to me. I do not want to give up my memory of the shrub, and I don’t want to give up my care for it. I don’t want to give up its meaning.

The branches shudder a bit in the wind. I was relaxed and felt the branches scraping the aged boards of the fence. The blackberries, fully yellow, flashed in me. The enormous fir beside the basswood grew more and more yellow, until yellow was not a recognizable color, and green was like a ghost shifting around the tree’s past. The tree is a blasted-out white and nearly approaching blue. This is my life, I think. A cloud passes over the fir and stops, darkening the tree. I face the table, I transfer the tree scene to its surface. The surface, with my head this close, stretches beyond my peripheral vision, so that it is ovular. I no longer care for the old plastic and instead experience the resonances of the bursting tree; it replays, each time less white and more yellow.

With my eyes turned toward the fence, suddenly I remember how to see it. It is as if I have been residing entirely in my interior since before I can remember. Yet I remember this feeling well. This is the earth. This is where I was created. I have never left. A larger bird passing over the driveway disappears and the gravel is not saturated in my vision; my vision adjusts but I do not forget the gravel is there. I see this driveway, set below the fence, as if I had only seen it in photographs. (Once or twice I have seen a photograph in the same way, realizing that I was looking transparently at an actual place.) I stand up and walk around the yard, becoming gradually tired and overwhelmed. I am extremely happy and have trouble bearing the possibility of wakefulness. If I let it pass through me, am I seeing it? Yes. I will be seeing it and it will be what I am, and I will not arrest it and I will not translate it or convert it. And when the conversion inevitably happens, because I am a remembering being, I will see the mental imagery in the same way, not as I see photographs, but as a texturally different occurrence of appearance. I will see the objects of my interior and exterior perception as equal and I will not have to remember my detachable position on the earth because I will feel detached, yet absolutely integral, just as I know stones are.

Stepping out of the space where the chicken lane ends and the yard becomes thick mounds of grass, strips of some greater core that is the grasses’ instructions—no, it is not the instructions, the genetic code is not the grasses’ core... the actual life of the grass, its being, is only related to the instructions—the grass blowing in strips of its own origins, its family fabric; I felt the give of the grass as I walked to the plastic table and sat down.

*

I wandered around the yard with my eyes, especially above where the towering trees cut the open air. My hands were cold so I put them in my pockets. In the space between the giant conical fir and the basswood was an enormous trapezoid of dull, brilliant light and it nearly touched my face it felt so near. The shed seemed excessively far away. The fenceline seemed to run straight from me to the shed; it was usually fifteen feet distant.

- - - - -

aka ‘_____ Mtn. Journals’

0 notes

Text

(Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals, or ‘Painting _____ Mountain’.)

8.

The marsh was full of reeds and waterbirds. It’s small and tucked between a farmer’s field and the gravel road skirting the mountain. Along runs a man-made ditch that stretches well beyond, cut off by the contour of an intersecting bank. This bank runs along the plains’ edge, into thoughtlessness, and eventually turns into the hills I see from the library.

I walk down the mountain to see this marsh. In the afternoon, it sees a very direct light only available in Fall. Joan showed me a picture of this swamp when it was lifeless: it was early winter and the light was blasted out so that everything was the color of salted asphalt. The picture itself presents a golden tone, with severe shadows, but this is certainly the camera and the hour. I can imagine the light as it might have been, harsh and emptying of substance. In the center of the picture is a heron she felt should not be there. Not so late in the year. It’s neither a sad picture, nor a happy one—hardly moral at all—but it was a warm day, she says, and there was a fish in the heron’s mouth.

Pelargonium on the window. Gojmir Anton Kos, 1969.

When I go to this marsh in late September in the afternoon, the light is a diffuse golden color that occurs to me as prehistoric. I almost always fall asleep in it, sitting on the edge of the swamp eating dried cranberries or whatever I bring with me. The reeds as object create no alarm in this light, but I try imagining a person in it. A person standing shin-deep in the water as the heron did. This person is looking me directly in the eyes, but I cannot see their face any better than the beaming gas meter at the house. I cannot hold my gaze. I turn to their eyes in glimpses then away toward their body. I have made no decisions about the body—its form, its size, but looking at them I feel the same finality of sexuality as with - - - - . I think if a person were in this light, they would appear pre-historic. And to appear prehistoric would be something like appearing at the beginning of the earth. This light is possible today! You can see it in people’s hair when they are directly below the sun or a strong artificial light. But in this swamp, the light would cover the entire person, leaving shadows dark like in Kos. You would see the contours of the bones around the eyes, the gutter of the neck; the shadows under the arms so richly dark they’d take on the weight of doubled limbs. To move in this light would nearly appear slower. A person would appear as on the earth; that is, as detachable.

- - - - -

Image:

https://www.rtvslo.si/kultura/razstave/gojmir-anton-kos-slikar-za-fotografskim-aparatom/240863#&gid=1&pid=1

1 note

·

View note

Text

Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals

April 6, 2020

- - - - - - - - -

7.

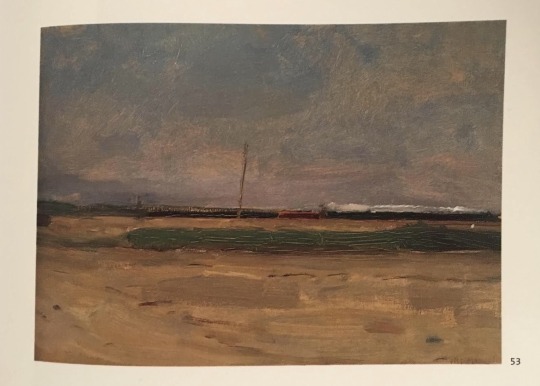

Another Mondrian. I’m paging through the same book from which I cut out Cows in an Orchard. I cannot translate Étendue sablonneuse at all. Listen—sand. This scene is so simple. It is 1907. It is the same blur as in pictures I’ve taken thoughtlessly crossing the West. Some farm field in Iowa. These scenes are nearly meaningless to someone unconcerned with agriculture in the Great Plains, or perhaps travel itself. Mondrian’s is a scene in the Netherlands. I look at it entirely as if it were Iowa. I do not consider Europe as in his other pictures. A scene like this is emotional to me in a way that little else is: it is the emotion of caring for a part of the world—in this case for a part of my life—that is not important in my self-view.

Étendue sablonneuse, vers 1907. Piet Mondrian.

Of course, I feel some pride in having traversed these extents of the world that are someone’s center. This scene I’ve known for only a matter of seconds. Though I’ve driven through these landscapes for days, they only stand now as perhaps hours of my life. It is not a scene to which I want to return for a lifetime, as I often feel, but I do want to go back. I want to go back and see it in a magnitude more proportionate to the amount of time I was there. I suppose I feel this way often. Yet there is no appropriate magnitude; no quantity of time demands anything particular from us. Still, I would like to be closer to the magnitude of the painting, of the pictures I’ve taken: enough to pause with some appreciation, some sense of rarity; some foresight.

*

The light in many of the Mondrians is very “eternal.” Though it did not last beyond the painted moment, I recognize it as the fabric of experience throughout life. As I see it many late afternoons or mid-mornings when it contrasts most distinctly with the outline of the fence, it seems to be a kind of light we would never fail to notice. It is not that it is outstandingly beautiful, though it is. It’s that I feel purpose in seeing it. Something beautiful may cause me to linger and feel a kind of obligation to it. To savor it, to explore it, to feel it. But I have no obligation to this light. Nor do I take it for granted. It is simply my world, it’s my life, people’s lives, the life of the world.

All light is the life of the world but this light has the unique trait of being apparent.

*

The house has five primary rooms, enough for a family. There are the cool rooms on the far side of the sun-gorged wall of the house. One is a bedroom with a closed door, and it contains two double beds, each with a heavy winter blanket folded at the pillow side to expose the fringe of shiny smooth fabric. The pillows are a dark red bordering on purple. The other shaded room is a library of sorts, with two walls of books reaching half-way up the wall and each spanning about eight feet across. One small window on the library wall faces the fields and it is fortuitously positioned so that through its square frame I can see through an opening in the woods to a single hill maybe a mile away. In this opening, the hills seem profoundly still and as if there were no sky behind, only above.

-

Image:

Janssen, Hans, and Joosten, Joop M. 2002. Mondrian de 1892 à 1914: Les chemins de l’abstraction. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. Pg. 109.

0 notes

Text

Palais Idéal in Hautrives

By Jacob Hallerström

This article was originally published by the Swedish magazine Profet, where Hallerström writes regularly. The text was translated into English by the author.

I’m going to Lyon from Béziers on a mystic morning train. It’s raining outside my train window and all of Provence turns into swamplands. Over the world lies a grey veil, like a quilt. In France the railwaymen are on strike. At the entrance of the train station I am handed a pamphlet; “pour le transport collectif!” says the curly headed lady from the SNCF and smiles at me. I am soaking wet and my fellow train passengers are just as wet as me. My destination for this day’s journey is the the tiny village of Hautrives.

Ferdinand Cheval was a French mailman who lived at the end of the 19th century. He lived and spent all his life in the region I’m travelling right now, north of the riviera and south of the alps. His daily work was delivering mail in and around his domestic village Hautrives. What makes Cheval worth this article I’m now writing is what he built.

According to his own notebooks the initial step toward what would develop into his life’s work was taken on a day in April 1879 when he was walking along a gravel road in Hautrives. From the gravel Cheval picked up a small rock that wore a peculiar, almost surreal shape. The mailman was astonished by what he had picked up. Cheval later wrote about the incident in his biography saying that the rock evoked a feeling of inspiration, a feeling so strong that he decided to build a palace with the rock as his template. This was the start of what would become Ferdinand Cheval’s Palais Idéal.

Palais Idéal, hand-built by Ferdinand Cheval.

He started in his small vegetable garden. He devoted his time while not working to grinding, sharpening and polishing stones and planning the building he had in his head. The vegetable garden was soon transformed, the construction site was enlarged and after 33 years of constant continuous construction by hand a completely unique building stood tall in the small French village of Hautrives. It was all made up, planned and built by Cheval himself and his hands.

Palais Idéal has a style, form and shape like nothing else. It can best be described as something of a metamorphosis of sandcastles and Hindu temples. Nobody has completely figured out where the architectural inspiration for the Palais Idéal came from. A likely theory is that the mailman saw and was inspired by postcards in circulation during this period. In the late 1800s motifs from countries like India, Burma, China, countries far from Hautrives and France, became popular themes on postcards.

Today the Palais Idéal is seen as a tour de force and supreme example of naïve art. Among the first people to shed light on Cheval’s creation were the surrealists of the 1920s. They loved and were exalted by this surreal building in the proper use of the term. André Breton was there, Pablo Picasso as well. They painted, photographed and studied the palace. They were blown away by the Palais, perhaps because the creation Cheval made stood and stands for something the surrealists held very high, dreams. Both the building itself and the story of how it was made are like things taken from surreal dreams.

Cheval’s mausoleum in Hautrives

Cheval’s wish was to be buried in his palais. This was not approved by the local authorities so at the very end of his life Cheval went to work on a mausoleum for himself and his wife in the town cemetery. Built in the same style as the Palais Idéal this is where Cheval today rests. For me the Palais Idéal shows a most fundamental form of expression. Cheval built his own world and his soul into the palais and standing eye to eye with the building is like standing eye to eye with a dream, a dream made of stone.

I’m on a train again. This time toward Marseille. Here in the valleys they make wine and the grapevines stand in lines with all their splendour. Beyond the horizon are the alps and they blow up like enormous air balloons above the valleys. The altitude is intoxicating.

#

See the original article below. Profet also has English-language content.

https://www.profetmusik.se/?record=palaisideal

0 notes

Text

6.

I never spent any time on the driveway side. But I could go to a garden shed with some tools and bags of topsoil, woodchips, and other miscellany. It had no windows and no door, just an oversized opening about five feet wide. The threshold was worn into the ground so that you walked both down and up to get through. Facing the house from this point, there is a plain wall; it is unadorned; none of the plants that cheer the front and back. The driveway butts right up to the side. An electric meter hung there alone by the window.

Returning home, I always continue along the driveway and enter through the back door, but today I am stopped at the wall. I looked at the electric meter. It was older than what you might see installed today, without the round bulging cylinder where the numbers are read. Instead, it had two smaller glass circles through which each reading is made. The afternoon sun, though not intense, was concentrated directly on the wall and it reflected strongly off the two glass circles. All of my attention was led toward the two circles, but my gaze would immediately divert away from the painful glare. I would look away from the wall entirely, or pass my eyes over the window. The sun on the dust gave it a color almost equal to the white of the house. That is, a color equal to my idea of the house. The siding was more yellow in this sun, so the window stood out as an unevenly toned white square. But I only occasionally saw this. The whole process was of reflexively moving my eyes away and toward the meter.

I shifted the sleeve of my t-shirt slightly with my hands, feeling the cold skin of my bicep. It warmed my hand as I left it in an exchange of heat with my body. The wall was maybe twenty feet away from where I stood at the front of the shed. I found myself staring at the wall and as I did it began to seem a deflated, almost ghostly form of green. As I made a minimal movement with my eyes, an afterimage appeared so that there were two houses in my field of vision; I purposely carried this new house toward the fence, where it appeared purple and green simultaneously. I considered the core of the afterimage to be purple but if I tried to look at its edges, which was perhaps impossible—my eyes could not move without moving the afterimage itself—they seemed hollow green.

I looked at my hand turned back-side up and dangling stiffly at my waist. I can fix my eyes on the center of my hand and still consider its edges. This comes more easily from certain distances. For instance, if I look at my hand held away about a foot, I can see its entirety without moving my eyes at all, and indeed the whole hand can become my focal point. I usually move my eyes instinctively, even at this distance; but it is possible to run over its surface using another mechanism, my eyes stationary. I can center different points in my visual grip; each becomes the center of a picture.

This seems to point to a seamless juncture where our internal visual field meets our external one. If, for example, I consider not the house before me but the present ovular visual field, fixed in place—which includes a trapezoidal-shaped wall, the lower sky, and fragments of trees and ground—I can scan across that entire field without moving my eyes. This may be a sort of internal, imagined scanning of the image at hand. Even if naturally I move my eyes rather than do this kind of explicit internal scanning, doesn’t each normal eye movement provide a new field that I could consider in the same way? That is, doesn’t every new view include an ovular field that is scannable in place?

Cézanne would have tracked the eyes’ movements as they situated perception of the object, and tried to include that in the painting. I'm artificially fixing my sight in one direction, trying not to move my eyes. Do these imagined approaches play any role in normal vision? So inseparable is the internal visual field from the external—they are in most respects the same—that their movements feel alike. If I close my eyes and activate a memory of the visual field, I can scan it with no eye movement at all—unless I move them beneath my eyelids!—but I move exactly like in normal vision. Can’t I do this with my eyes open? It is as if we can use vision as a basis for an internal map, then use its images to navigate the external. All of this pointing to a self that is equally engaged with the internal and external and ingeniously confused about the difference between the two.

On the one hand, it may be that imagination is simply impressive—we can generate viewpoints if we try; but perhaps a way to scan an external visual field without moving our eyes is to imagine our movement—centering points or even envisioning approaches from other angles. This would seem to generate a cascade of new images taken from various perspectives. But I doubt we need these images in normal vision: there is no one in us to see them. If we have this imaginative ability, it may benefit from the way in which we construct vision in the first place. The map may not be made of conscious frames, or points of view; it may be made of potentials—that is, for merging imagined, incomplete contact with direct contact to create a visibility more elaborated than front-facing surfaces would allow. It suggests that the head-on point of view represented in perspectival painting may not actually exist for us because we always know more than a single perspective would indicate. ‘Direct’ would lose meaning, as would ‘imagined’, if there was no way to see an exclusively front-facing perspective in the first place.

A photograph of a scene depicted by Paul Cézanne.

We know the far side of the cup without any light touching our eyes. What is imagination when it does not provide a complete image, when it gives us the back of the cup anyway?

(Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals)

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/a-An-example-of-a-scene-depicted-by-Paul-Cezanne-Millstone-and-Cistern-under-Trees-La_fig7_263285829

*Update 4/5/20*

Shortly after posting, I saw a brief 15-minute lecture by Berkeley professor Alva Noë that very closely follows these questions:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xhk9MkTkSPA

Also, the section referring to imagined, incomplete contacts was edited shortly after posting. This was particularly difficult to make clear, especially to myself. I also deleted the last line about Cézanne, which I realized was misleading.

0 notes

Text

5.

The house was laid out and furnished so that each room felt alone and involved at the same time. It was surprising to notice this right away—it seemed like the kind of observation that would arrive after some steeping and reflection. But it stood out immediately and seemed to be a feature of the house. I felt a lightness to the building, even amongst the dark woods of the walls and the cool back rooms that stayed in shadow all day.

I had an old art book of Mondrian that I’d bought because it was in French. Yesterday I cut one of the pictures out, something I don’t normally do, but I wanted to separate it from the book and its other images. It’s called Vaches dans un verger, which I’m guessing translates to Cows in an orchard. The reason I lingered on the painting was: one, it suggested the texture of a common dream; and two, it strongly paralleled the sense of the yard in which I was now sitting.

The book said that with the painting, Mondrian had searched for connections between the styles of Van Gogh and the palette of Monet. In it the cows are no more pronounced amongst the low trees than the orchard itself. This reminds me of the Van Gogh I often hang, of gardens and a man working in a plot. I only notice the man every few months. The thing I doubt about the Mondrian is that I would ever see the cows’ fur with same gleam of oil paint he uses in the sky. Something else may equalize their appearance, but the glare would seem restricted to truly reflective surfaces. Perhaps he’s saying the painting is made of paint: the gleam is not material to the orchard, but to the canvas.

The picture’s sky is visible in an unsentimental but idyllic light that waits behind the trees. I say waits because I don’t believe it comes to you; you go outward. This is some of its dreamlike, aspirational quality. It is the way I feel about the yard. But nothing is beyond reach, nothing is beyond the grasping potential of our eyes. And nothing enters the abstract, including the sky. The sky is amongst the orchard’s trees—at fifteen feet of distance. Even as the trees stretch wildly into the air, the view is such that all the noise of branches meets at one plane in vision—without sturdier points of reference, depth doesn’t seem to occur. The earth does not provide the reference because it takes no precedence over the branches.

Cows in an Orchard. Piet Mondrian, around 1902-1903.

Distance tilts up toward me. In the yard, at all distances I can feel the closeness of things that are not in my hands or touching my face. They are all close enough that I can bring them into my mental space with a fluid gesture that takes no effort. There is less separation between my mental imagery and my exterior perceptual field. I look at the cows again and think about Mondrian’s choice to mix them into the chaos of the “Van Gogh-like” strokes. When the cows are the protagonists, we shift our focus toward them and emphasize their presence in the picture. But to see the cow within the fabric of the orchard is not to think she is less alive. The picture seems to assert that the trees are no less alive, which of course we have risked saying throughout modern history. They are participating; the trees and the unhurried light are involved. I look down at the blunt plastic of the table, its texture made matte by weather. This texture of plastic has a calming effect in a way that new plastic often does not. New plastic can be far more violent.

(Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals)

Janssen, Hans, and Joosten, Joop M. 2002. Mondrian de 1892 à 1914: Les chemins de l’abstraction. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. Pg. 81.

0 notes

Text

4.

It was almost cold that morning and the creek looked black. The mud of the dark humus was warmer than the air; it held yesterday’s warmth. The image of the mud circled in me, as song, while I walked up the mountain road. Turning on the kitchen faucet, I ran some water over some salad greens and toweled them off with a kitchen rag. I chopped the lettuce, carefully poured olive oil on the leaves, and sprinkled salt faintly over it all.

These I ate at the table by the kitchen window. Everything was more generalized from this point of view, by comparison to sitting out by the chicken lane. My eyes moved differently. While in the yard, in order to see its entire width, I move my eyes their full horizontal capacity, often adjusting my head as well. Inside, with the fence only a few feet further, I move my eyes perhaps two-thirds of their horizontal reach to see the same objects.

I had put on some music and it filled the house thickly. It was not a loud well-balanced stereo, just a portable radio playing the public classical station through cheap speakers. The thickness came from the song, which was piano music, a medium-tempo and oddly structured solo performance. The high notes were bell-like in the tinny speakers and the lowest notes caused a sort of static that physically shook the loosely-attached speaker against its plastic case. The middle of the scale, however, rang out in clear notes. The contrast between the clarity of those mid-range notes and the other, more distorted sounds caused the clear notes to become significantly pronounced, as if closer to the ear. And because the room was small and the music filled it so completely, the closeness was of a different sort than if I were facing the speakers at a distance. It became almost interior, as with headphones, so the notes were perhaps within the space of my sense of self. They seemed to enter the place from which I regard my body and the world around me.

Still Life with a Bottle and Yellow Drapery. Gojmir Anton Kos, 1965.

The odd variable structure of the music meant that there were constant movements between the octaves, which made it seem like the extremes of the range were a ground for the mid-range and that they actively lifted it up. The lifted sounds, though made of single notes, are revisited so often in the phrases that they take on a body, as if the result of a cluster of atoms bonding to make a thing. This emergent, flat thing, placed squarely between my eyes, would nearly fade away when occasionally the mid-notes went unvisited. Then the song would buoy them back up again just in time, with the added benefit of having left my senses refreshed and less expectant, so that I was continually attached.

The salad was good but my plate had been empty for a half hour, so I made another. I switched off the radio and started to become bored. It was lonely up here, and though I often forgot the problem, I felt it almost immediately after I arrived. I wanted someone else to see the view of the hills off the mountain, the simple beauty of the house, to cook a big dinner with me. Sometimes I cook more elaborate dishes up here, but there is a certain heaviness to the energy of relishing a good meal alone that I don’t want to feel too often. A meal with a friend is often incredibly light, even as the passion for the food increases. However, tonight I thought I’d take more time cooking and drink some wine with the meal. I was becoming exhausted with the feeling of looking at the world. I thought I should relax and be completely guided by a fixed set of possibilities. I wanted the food to taste good, so I couldn’t wander off. Cooking and drinking wine would tell me what to do.

(Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals)

https://www.ng-slo.si/en/307/still-life-with-a-bottle-and-yellow-drapery-gojmir-anton-kos?workId=3603

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

3.

There was a plastic table and chairs beside the wire fencing of a chicken shelter. I slid the table over a bit because I noticed the grass below starting to brown and die. There weren’t any chickens, but their lane still showed all the signs of life: little patches of cleared ground scratched away by the hens, and piles of old kitchen scraps that had become uninteresting. In the center of the lane sat a glowing pile of sticks—someone had raked what had fallen from the basswood and left it there.

The yard was not large, and a gravel driveway split it in two. The basswood hovered over it all, shading the house at noon and letting the sun back in around three. I looked toward the fence and fixed on the vines that climbed over the top. The other side, I knew, had been clearcut for a house that was never built. Blackberry covered the vast lot in a brambly mass. Beyond, hills descended into a valley and another mountain rose up again. The basswood was one of the few trees the timber company had spared, and it had doubtlessly grown much larger and rotund in the years since the forest disappeared around it.

The plants on the fence were still the same mix of vines and flowering bushes that the neighbors had planted. Once the neighbors would have seen these plants from the window of their camper, before they tore down its outbuildings and the barbecue pit and sold the property. This is what I imagined. I don’t know the local history. But I walked through the brambles and found old bricks from a bonfire pit, cement blocks forming steps to where a screen-door may have been, and bits of trash strewn around, mostly old screws but also a fishing boat’s outboard engine. Perhaps someone had died and the property was hastily sold. As it was, old stumps, never rooted out, sat amongst the blackberry that swallowed them.

I wasn’t thinking this image, but it laid behind my vision as a kind of background information. The experience of walking around the lot, what I imagined and deduced in poking around, gave a color and a mood to my view of the fence. But this mood toward the fence barely resembled the feeling of actually walking around on the other side. In the way that yellow is lost with blue in making green, my mood could not exist without the brambles, but the original experience was unrecognizable in this new combination.

Though the sun was pleasantly warm on my face, my hands were cold in the mid-morning air so I stuffed them in my jeans-pockets to warm them. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine a chicken in the lane. They scratched around the corners of the stick-pile looking for worms, clearing the earth and leaving the bare patches I see now. Their fatty wattles were an inconsistent red. The motions of the head were abrupt as they pecked at the ground they had cleared. The pile of sticks is twice their size and they duck below an opening and trundle inside. I cannot see it, but there are flecks of red that occasionally flicker from deep in the pile. Another chicken, this one black—the other chicken’s body doesn’t have a color—wanders around doing the same. I can’t see them anymore and I try to imagine their face but I suddenly see a human foot. When I open my eyes, the yard looks very rich and bright. Not only are my eyes slightly more sensitive to the light, having dilated while they were closed, but things have also taken on a new sensuality. I hadn’t felt this all day, but I recognize it. It feels nearly sexual.

Occasionally when I wake up in bed, I keep my eyes closed and see an imagined room with the vividness of waking life. I try to do this now, but it is nearly impossible. The imagined chickens lack the feeling of wakeful perception. In bed, internal perception seems nearly identical to external perception, as if my eyes were open. I can remember that atmosphere of detail—my surprise—but I cannot simulate it here, my body roused. In fact, I doubt I remember much: it may be a kind of abstraction, or an extracted understanding. If I recall a dream, for example, I remember that it felt real but I can no longer access my acceptance; it feels like an image on the other side of something. In parting the dream, I feel my acceptance slipping away, as if a substance were pouring out. I’m left with a question: does the image actually look like external perception, or does it only feel like seeing outside? It seems possible that the mental image is less distinct, less richly detailed than the external interaction, but that it is accompanied by a chemical atmosphere that is similar to wakeful life. A feeling of realness.

Still Life with Melons, Vase, and Rug. Georgette Agutte, 1912-1914.

The radio is playing softly at the neighbors’ house a few hundred yards through the woods, which must mean it is playing very loudly. Across the distance, the sound is so low that I can barely make out a melody. I pull my hands from my pockets and walk into the house, flicking on a light in the kitchen and filling a glass of water. I walk back into the yard and sit down, looking up into the canopy of the giant basswood, which by now is completely in front of the sun. Its leaves and branches are sparse so light makes it to the house in measure. I take a deep breath and look toward the fence. It is fifteen feet away, with old boards losing the effect of the original staining. At this distance, I can see details on the fence nearly as easily as the table before me. The boards are knotty and the grain of the wood is raised high by time, the space between the grains wider than on a freshly cut board. The sky above the fence has no such definition. Without clouds it is simply flat. I often wonder about why the distance of fifteen feet is so meaningful but at the moment I don’t try.

https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Sites-thematiques/Musees/Nos-musees/Valorisation-des-collections/Les-femmes-artistes-sortent-de-leur-reserve/Icones/Agutte-Georgette

(Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals)

1 note

·

View note

Text

2.

If you walk a little ways below the house, you find a small stream that opens into a gulch. I open the gate to the back yard and go out. Branches hang fairly low on the right side as I walk, and I run the leaves over my hands where they are sufficiently low. I cut off at the stream where it meets the road.

It always seems quieter back here than at the house, but with the creek I doubt there is any less sound. Perhaps it is the dip below the low branches as you enter the woods, or the sudden darkness of the interior that creates the effect. It is as if there is more noise of light on the road, more noise of thought. But the woods always grows louder as I go further along the creek. I start to think and experience mental images more intensely.

I wandered back and forth across the surface of the creek, finding stones planted securely enough to handle my step. The radio is playing at the neighbors’, unintelligible but with a regular texture that is immediately recognizable as country music. A salamander is on a log, completely still.

This is the first time in a week that I have noticed the life of another being with the same force of interest as I regard myself. The salamander is walking across a wet log and its smooth skin is nearly black—nearly more than black! I think—and its patches match the white moss growing on the bark. The salamander starts moving and blinks their eyes. Each step is made with two arms or legs at the same time. My face is less than two feet from their body and I back away. I do not know what the salamander is thinking. I recede back into myself after deciding I should leave them alone. I don’t have the power or interest to go deeper into the feeling: another being holding the same presence I assume for myself. I do think, however, that it would be nice to lose that interest in myself for a while. To see everything more or less as I see the woods.

*

Pelargonium. Gojmir Anton Kos, 1969.

Everything was silent. Everything is silent. The muffled rustling of a small animal makes itself present somewhere up one of the hillocks. The woods is so still, the sound of the radio so low, the creek so muted, that the trees begin to appear as if out of nowhere. There is a striking green glow to their boundaries with the air, as if they were all shoots of new plants. These are beech trees, elephant gray trees with patient leaves. One is in my hand. The silence is so apparent that I am almost hit by it, and as if playing along with the idea, I lay down. The beech leaf is on my forehead. As my eyes wander through the forest, they fix first on the trunks of the narrow beeches and their green emanations. It seemed they were appearing one at a time like an animation, from slide to slide, version to version of the woods, placed one in front of the other in succession. But the animation would be modern—each tree appeared gradually and softly, even within the space of a millisecond. To play it back in my mind took longer than it had unfolded in the first instance. The green glow came first, and the elephant skin and eye-shaped black knots appeared second. It was similar to what you’d experience watching clouds pass, except the shapes weren’t cloudlike. This was my memory of it, and I had doubts that it transpired that way. No, this is not my memory of it. It is my attempt to visually create the phenomenon in my mental imagery—because the phenomenon was not visual. It was a corporeal sensation such as vision is, but I am creating a type of translation in visualizing it.

The silence is continuing longer than expected and I try to hold on. The rustling of the squirrel continues and I look further up the trunks toward the canopy. This is the same sky as it appeared through the branches in Mondrian’s orchard; as it appears through the basswood; and as it appears above the fence, as I carry it into the blackberry bramble and cause it to appear as from the ground, as if the ground below were open and the bramble was the roof of some atmosphere; blunt, charged white. The wind is not direct enough to cause a single path for the branches of the canopy. Its mass is turbulent and calm in the gentle breeze and I watch it with this leaf on my head, grateful for my life. I think—and the silence is gone—that I am grateful for the life of the world. My hands are waving above my body, then flat on the moist beech leaves that have fallen earlier than any others. I stand up and walk to the creek, making my way back to the house.

(Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals)

https://www.rtvslo.si/kultura/razstave/gojmir-anton-kos-slikar-za-fotografskim-aparatom/240863#&gid=1&pid=1

0 notes

Text

Landscape on the Island of Rab. Gojmir Anton Kos, 1947.

1.

I started up the path, which was basically a ditch. It was difficult to stay balanced and my feet were continually forced toward each other by the angle of the ground. I wobbled along carelessly, as if the morning air could catch me. Nothing could grow on the path itself; the clay was exceptionally compact and smooth, acting like a pavement. Its depth suggested obsession.

Dry grass overtook the path from its sides and I straightened up. The windows of the house were dull and wet at nine, shielded from the morning light by an enormous basswood on the other side of the roof. I saw the knee-high cliffs of the ditch and the tufts of yellow grass. The tufts were spiky and crowded and I thought heliocentric, though I would not choose the word to evoke an image of the grass. By using it I had a symbol that stimulated something unavailable by any other accompaniment: it was not a matter of more or less accuracy, but of how I liked to see it. The tufts formed ball shapes, like sunflowers with only-suggested disks. Empty sunflowers. All of the roots met together in a patch of ground and grew outwardly at disarrayed angles, giving the appearance of petals. The blades of grass orbited a mid-point which was not really there, but which I saw.

A stubby fruit tree appeared on the right side of the path, and I ducked under it to avoid its branches. Barely touching it, wet dew slid off the leaves onto my shoulder. The house is small with a single wall in front and I recalled opening its dewy windows to the yard and the mountain road beyond the gate. Though fields and foothills spread out impressively in the distance, I couldn’t see any of it due to the high trees across the road. The trees were thick and in early September retained the new green of spring, a pale neon color like inchworms’. The green was consistent, almost to the point of affecting the bark itself. I thought of a landscape by Gojmir Kos. The painting is a wide expanse taken from a diagonal, of farm fields and marsh and the sea in the distance. Though in the mass of green I saw neither fields nor sea—nor the exact boundaries of farming so failed by his paint—I was reminded of him in the chaotic fray of the woods. Or, the fray was association: the woods in front of me was well-organized. It seemed to order itself in parts as in Landscape on the Island of Rab, wherein separation does not come by the farmer’s logic, but by the logic of visibility. Its lines do not serve anyone’s ends. So they fail at the border of the hayfield and the thicket, the thicket and the shadowy lane, the brown pasture and the sea. In Kos’ painting, including still-life, objects and ideas do not govern boundaries; categories arise by common appearance. The woods was like this: the form of the leaves, the branches, and the trunks occupied one visual category—translucent green—while two other worlds stood beside: cold shadow and escaped yellow.

(Excerpt from _____ Mtn. Journals)

https://www.ng-slo.si/en/307/landscape-on-the-island-of-rab-gojmir-anton-kos?workId=3608

1 note

·

View note