#yale rumpus

Text

Accepted! “Good Girls Don’t Get Stoned.”

Accepted! “Good Girls Don’t Get Stoned.”

After a week of a “Dear Writer: NO” rejection each day from excellent magazines—The Mississippi Review, Upstreet, The Yale Review, The Rumpus, and Joyland—it was a joy to receive an acceptance from Fresh Ink! “Good Girls Don’t Get Stoned” is one of the short stories I culled from my first and as-of-yet unpublished novel, As […]Accepted! “Good Girls Don’t Get Stoned.”

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roxane Gay is an American writer, professor, editor, and social commentator. She is the author of The New York Times best-selling essay collection Bad Feminist (2014), Hunger (2017), Ayiti (2011), An Untamed State (2014), and Difficult Women (2017). She was previously a professor at Eastern Illinois University, Purdue University, and Yale University. In addition to her many publications, she is an opinion writer at The New York Times, founder of Tiny Hardcore Press, essays editor for The Rumpus, co-editor of PANK, and editor of Gay Mag. Much of Gay’s work deals with the analysis and deconstruction of feminist and racial issues through the lens of her personal experience with race, gender identity, and sexuality.

0 notes

Link

One of my favorites, Mina Kimes, Yale grad and once, Yale’s hottest girl for the newspaper Rumpus.

Kimes has more than half a million followers on Twitter, and says she has blocked and muted thousands of abusive or otherwise unpleasant accounts over the years. “Nobody thought of me as a NFL analyst for a long time,” she says. “When I first got into talking about football, [women’s stuff] was all I was asked to do on television. I’d have to be like, actually, I really have a lot of opinions about the Ravens’ offense.” She’s learned to shut things out: “I need to be very deliberate about what I look at, what I allow to enter my brain.”

Early on, “it used to drive me crazy. I would do shows and I would be on with these former athletes who would get so much stuff wrong and nobody would care. I would get one tiny thing wrong and get destroyed.” Now, she says with a laugh, “people are so used to seeing me. That’s what equality is: fucking up equally.”

0 notes

Photo

The Cardiff Giant part 2 Newell set up a tent over the giant and charged 25 cents for people who wanted to see it. Two days later he increased the price to 50 cents. People came by the wagon load. Archaeological scholars pronounced the giant a fake, and some geologists even noticed that there was no good reason to try to dig a well in the exact spot the giant had been found. Yale palaeontologist Othniel C. Marsh called it “a most decided humbug.” Some Christian fundamentalists and preachers, however, defended its authenticity. Eventually, Hull sold his part-interest for $23,000 (equivalent to $429,000 in 2015) to a syndicate of five men headed by David Hannum. They moved it to Syracuse, New York, for exhibition. The giant drew such crowds that showman P. T. Barnum offered $50,000 for the giant. When the syndicate turned him down, he hired a man to model the giant’s shape covertly in wax and create a plaster replica. He put his giant on display in New York, claiming that his was the real giant, and the Cardiff Giant was a fake. As the newspapers reported Barnum’s version of the story, David Hannum was quoted as saying, “There’s a sucker born every minute” in reference to spectators paying to see Barnum’s giant. Over time, the quotation has been misattributed to Barnum himself. Hannum sued Barnum for calling his giant a fake, but the judge told him to get his giant to swear on his own genuineness in court if he wanted a favorable injunction. On December 10, Hull confessed to the press. On February 2, 1870 both giants were revealed as fakes in court. The judge ruled that Barnum could not be sued for calling a fake giant a fake. The Cardiff Giant appeared in the 1901 Pan-American Exposition, but did not attract much attention. Iowa publisher Gardner Cowles, Jr. bought it later to adorn his basement rumpus room as a coffee table and conversation piece. In 1947 he sold it to the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, New York, where it is still on display. The owner of Marvin’s Marvelous Mechanical Museum, a coin-operated game arcade and museum of oddities in Farmington Hills, Michigan, says that the replica on display there is Barnum’s replica. #destroytheday https://www.instagram.com/p/CE63aLwB_sg/?igshid=vz0olgvau8ut

0 notes

Text

Rape Culture Readings

Abdullah-Khan, Noreen. Male Rape: The Emergence of a Social and Legal Issue (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Angelou, Maya. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (Ballantine, 1969).

Armstrong, Elizabeth A., Laura Hamilton, and Brian Sweeney, “Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel, Integrative Approach to Party Rape,” Social Problems, vol. 53, no. 4 (2006), pp. 483–99.

Azoulay, Ariella. “Has Anyone Ever Seen a Photograph of a Rape?” in The Civil Contract of Photography (MIT Press, 2008)

Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (University of Chicago Press, 1995).

Bevacqua, Maria. Rape on the Public Agenda: Feminism and the Politics of Sexual Assault (Northeastern University Press, 2000).

Block, Sharon. Rape and Sexual Power in Early America (University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

Boswell, A. Ayres and Joan Z. Spade, “Fraternities and Collegiate Rape Culture: Why Are Some Fraternities More Dangerous Places for Women?” Gender & Society, vol. 10, no.2 (1996), pp. 133–47.

Brison, Susan. Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of a Self (Princeton University Press, 2003).

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape (Simon & Schuster, 1975).

Buchwald, Emilie, Pamela Fletcher, and Martha Roth, eds., Transforming a Rape Culture (Milkweed, 2005).

Bumiller, Kristin. In an Abusive State: How Neoliberalism Appropriated the Feminist Movement against Sexual Violence (Duke University Press, 2008).

Burstyn, Varda. The Rites of Men: Manhood, Politics, and the Culture of Sport (University of Toronto Press, 1999).

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (Verso, 2016).

Campbell, Kirsten. “Legal Memories: Sexual Assault, Memory, and International Humanitarian Law,” in Signs, vol. 28, no. 1 (2002), pp. 149–78.

Cappiello, Katie and Meg McInerney, eds., SLUT: A Play and Guidebook for Combating Sexism and Sexual Violence (Feminist Press, 2015).

Celis, William. “Date Rape And a List At Brown,” The New York Times, November 18, 1990.

Clark, Annie and Andrea Pino, We Believe You: Survivors of Campus Sexual Assault Speak Out (Holt Macmillan, 2016).

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me (Spiegel & Grau, 2015).

Connell, R. W. Masculinities, 2nd ed. (University of California Press, 2005).

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review, vol. 43, no. 6 (July 1991).

Critical Resistance and Incite!, “Statement on Gender Violence and the Prison Industrial Complex,” in The Color of Violence: INCITE! Anthology (Duke University Press, 2016).

Davis, Angela. “We Do Not Consent: Violence Against Women in a Racist Society,” in Women, Culture, and Politics (Vintage, 1990); “Rape, Racism, and the Myth of the Black Rapist,” in Women, Race, and Class (Vintage, 1983).

Deer, Sarah. “What She Say, It Be Law” in The Beginning and End of Rape (University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

Dick, Kirby and Amy Ziering, The Hunting Ground: The Inside Story of Sexual Assault on American College Campuses (Skyhorse, 2016).

Dworkin, Andrea. Intercourse: Occupation/Collaboration (Free Press, 1987).

Enloe, Cynthia. “Wielding Masculinity inside Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo,” in Globalization and Militarism: Feminists Make the Link (Rowman and Littlefield, 2016).

Estes, Steve. I Am a Man! Race, Manhood, and the Civil Rights Movement (University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

Estrich, Susan. Real Rape (Harvard University Press, 1987).

Factora-Borchers, Lisa ed., Dear Sister: Letters from Survivors of Sexual Violence (AK Press, 2014).

Falcon, Sylvanna. “Rape as a Weapon of War: Militarized Border Rape at the U.S.-Mexico Border,” in Women and Migration in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands: A Reader, edited by Denise A. Segura and Patricia Zavella (Duke University Press, 2007).

Feimster, Crystal. Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (Harvard University Press, 2011).

Filipovic, Jill “The Conservative Gender Norms That Perpetuate Rape Culture, And How We Can Fight Back” in Yes Means Yes (2008)

Flanagan, Caitlin “The Dark Power of Fraternities,” The Atlantic, March 2014.

Freedman, Estelle. Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation (Harvard University Press, 2013).

Friedman, Jaclyn and Jessica Valenti, Yes Means Yes!: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (Seal Press, 2008).

Funk, Rus Ervin. “Queer Men and Sexual Assault: What Being Raped Says about Being a Man,” in Gendered Outcasts and Sexual Outlaws: Sexual Oppression and Gender Hierarchies in Queer Men’s Lives, edited by Chris Kendall and Wayne Martino (Harrington Park Press, 2006).

Gay, Roxane. “Peculiar Benefits,” The Rumpus, May 16, 2012.

Gilmore, David. Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity (Yale University Press, 1991).

Goldin, Nan. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1989); Nan One Month After Being Battered (color photograph, 1984)

Gottschalk, Marie. “Not the Usual Suspects: Feminists, Women’s Groups, and the Anti-Rape Movement,” in The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Griffin, Susan. “Rape: The All-American Crime,” Ramparts Magazine, September 1971.

Halley, Janet. “The Move to Affirmative Consent,” Signs: Journal of Women and Culture (2015).

Harding, Kate. Asking for It: The Alarming Rise of Rape Culture—and What We Can Do about It (Da Capo, 2015).

Harding, Kate. Asking For It (De Capo Press, 2015).

Hartman, Saidiya. “Seduction and the Ruses of Power” in Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford University Press, 1997).

Hasday, Jill Elaine. “Contest and Consent: A Legal History of Marital Rape,” California Law Review, vol. 88, no. 5 (2000).

Hesford, Wendy. “Witnessing Rape Warfare: Suspending the Spectacle,” in Spectacular Rhetorics: Human Rights Visions, Recognitions, Feminisms (Duke University Press, 2011).

hooks, bell. “Understanding Patriarchy.”

Jarvis, Christina. The Male Body at War: American Masculinity during World War II (Northern Illinois University Press, 2003).

Jones, Gayl. Corregidora (Beacon, 1987).

Kahlo, Frida. A Few Small Nips (painting, 1935)

Kimmel, Michael. Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era (Nation Books, 2015).

Kimmel, Michael and Abby Ferber, eds., Privilege: A Reader (Westview Press, 2016).

Kimmel, Michael Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men (Harper Perennial, 2009).

Kollwitz, Käthe. Raped (etching, 1907)

Krakauer, Jon. Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town (Anchor, 2015).

Law, Victoria. “Sick of the Abuse: Feminist Responses to Sexual Assault, Battering, and Self-Defense,” in The Hidden 1970s: Histories of Radicalism, edited by Dan Berger (Rutgers University Press, 2010).

Leo, Jana. Rape New York (Feminist Press, 2011).

Levy, DeAndry. “Man Up,” The Players’ Tribune, April 27, 2016.

Luibheid, Eithne. “Rape, Asylum, and the U.S. Border Patrol,” Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border (University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

Luther, Jessica. Unsportsmanlike Conduct: College Football and the Politics of Rape (Akashic, 2016).

MacKinnon, Catherine. “A Rally Against Rape,” in Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law (Harvard University Press, 1988); “Rape: On Coercion and Consent,” in Toward a Feminist Theory of the State (Harvard University Press, 1991).

Marcus, Sharon. “Fighting Bodies, Fighting Words: A Theory and Politics of Rape Prevention,” in Feminists Theorize the Political, edited by Judith Butler and Joan W. Scott (Routledge, 1992).

Mardorossian, Carine M. Framing the Rape Victim: Gender and Agency Reconsidered (Rutgers University Press, 2014).

McGuire, Danielle. At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance—A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (Vintage Books, 2011).

McIntosh, Peggy. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”

Meyer, Doug. “Gendered Views of Sexual Assault, Physical Violence, and Verbal Abuse,” in Violence against Queer People: Race, Class, Gender, and the Persistence of Anti-LGBT Discrimination (Rutgers University Press, 2015).

Morrison, Toni. The Bluest Eye (Vintage, 1970).

Morrison, Toni ed., Race-ing Justice, En-Gendering Power: Essays on Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas, and the Construction of Social Reality (Pantheon, 1992).

November, Juliet. “It Takes Ass to Whip Ass: Understanding and Confronting Violence Against Sex Workers: A Roundtable Discussion with Miss Major, Mariko Passion, and Jessica Yee,” in The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities, edited by Ching-In Chen, Jai Dulani, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (AK Press, 2016).

Pascoe, C.J. and Jocelyn A. Hollander, “Good Guys Don’t Rape: Gender, Domination, and Mobilizing Rape,” Gender & Society, vol. 30, no. 1 (2016), pp. 67–79.

Pascoe, C.J. and Tristan Bridges, eds., Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Continuity and Change (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Patterson, Jennifer ed., Queering Sexual Violence: Radical Voices from Within the Anti-Violence Movement (Riverdale Ave Books, 2016).

Peek, Christine. “Breaking out of the Prison Hierarchy: Transgender Prisoners, Rape, and the Eighth Amendment,” Santa Clara Law Review, vol. 44, no. 4 (2004).

Prickett, Sarah Nicole. “Your Friends And Rapists,” December 16, 2013.

Puar, Jasbir. “Abu Ghraib and U.S. Sexual Exceptionalism,” in Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Duke University Press, 2007).

Reeves Sanday, Peggy. Fraternity Gang Rape: Sex, Brotherhood, and Privilege on Campus (NYU Press, 2007).

Richie,Beth E. Arrested Justice: Black Women, Violence, and America’s Prison Nation (Duke University Press, 2012).

Ristock, Janice L. Intimate Partner Violence in LGBTQ Lives (Routledge, 2011).

Ritchie, Andrea. “Law Enforcement Violence against Women of Color,” in The Color of Violence: INCITE! Anthology (Duke University Press, 2016).

Roberts, Mary Louise. What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Rumney, Philip “Gay Male Rape Victims: Law Enforcement, Social Attitudes and Barriers to Recognition,” International Journal of Human Rights, vol. 13, nos. 2–3 (2009).

Russell, Diane. Rape in Marriage (Macmillan, 1982).

Sapphire, Push (Knopf, 1996).

Scully, Diana and Joseph Marolla, “‘Riding the Bull at Gilley’s’: Convicted Rapists Describe the Rewards of Rape,” Social Problems, vol. 32, no. 3 (1985), pp. 251–63.

Sebold, Alice. Lucky: A Memoir (Back Bay, 2002).

Simmons, Aishah Shahidah. “NO! The Rape Documentary” (film, 2006).

Simmons, Aishah Shahidah and Farah Tanis, “Better off Dead: Black Women Speak to the United Nations CERD Committee,” The Feminist Wire, September 5, 2014.

Stone, Lucy. “Crimes Against Women,” Women’s Journal, June 16, 1877; “Pardoning the Crime of Rape,” Woman’s Journal, May 25, 1878.

Sulkowicz, Emma. Self-Portrait (performance, 2016); see also Conversation: Emma Sulkowicz and Karen Finley (YouTube video, 2016)

Sussman, Eve. The Rape of the Sabine Women (video-musical, 2007); Giambologna, The Rape of the Sabine Women (marble sculpture, 1583)

Syrett, Nicholas L. The Company He Keeps: A History of White College Fraternities (University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Haymarket, 2016).

The Chrysalis Collective, “Beautiful, Difficult, Powerful: Ending Sexual Assault Through Transformative Justice,” in The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities, edited by Ching-In Chen, Jai Dulani, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (AK Press, 2016).

The Hunting Ground (film, 2015).

Thuma, Emily. “Lessons in Self-Defense: Gender Violence, Racial Criminalization, and Anticarceral Feminism,” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 43, nos. 3–4 (fall/winter 2015).

Tracy, Carol E. et al., “Rape and Sexual Assault in the Legal System,” Women’s Law Project (2012).

Traister, Rebecca. “The Game Is Rigged,” New York Magazine, November 2, 2015.

Van Syckle, Katie. “Hooking Up Is Easy To Do,” New York Magazine, October 18, 2015.

Walker, Kara. My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love (exhibition, 2007)

Wells, Ida B. “ Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases” (1892), “A Red Record” (1895), “Mob Rule in New Orleans” (1900).

White, Janelle. “Our Silence Will Not Protect Us: Black Women’s Experiences Mobilizing to Confront Sexual Domestic Violence,” in The Color of Violence: INCITE! Anthology (Duke University Press, 2016).

Williams, Sue. Irresistible (sculpture, 1992)

Zirin, Dave. “How Jock Culture Supports Rape Culture, From Maryville to Steubenville,” The Nation, October 25, 2013.

Zirin, Dave. “Jameis Winston’s Peculiar Kind of Privilege,” The Nation, December 5, 2014.

Zirin, Dave. “Steubenville and Challenging Rape Culture in Sports,” The Nation, March 13, 2013.

“In the Shadows: Sexual Violence in U.S. Detention Facilities; A Shadow Report to the U.N. Committee Against Torture” (2006).

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

IF THERE EXISTS a mental-illness diagnosis as scary as the physical-illness diagnosis of cancer, schizophrenia may be it. To the general public, it’s a monolith of a condition: the one where you hear voices in your head and talk to people who aren’t there. That Beautiful Mind guy had it, and he invented Ed Harris completely, remember? But the words and stories of those who live with schizoaffective disorder offer proof that it’s a spectrum illness, which manifests with great variety and defies stereotype. And though it’s a serious diagnosis, many of those afflicted insist that they are not doomed.

The classic schizophrenia memoirs include The Quiet Room: A Journey Out of the Torment of Madness (1994), by Lori Schiller and Amanda Bennett, and The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness (2007), by Elyn R. Saks. Both books are frightening. Schiller’s illness manifested as voices shouting at her relentlessly to kill herself, and the treatment she was given early in her illness was cruel and unhelpful. Her account is perforated by memory loss because of trauma and electroconvulsive therapy. Saks’s book is a story of extraordinary willpower; rather than seek help, she hid her debilitating symptoms almost entirely while racking up degrees and honors in the legal and medical fields. Her writing voice is a little nerdy, but her achievements, which include a MacArthur “genius” grant, are extraordinary.

Esmé Weijun Wang’s new book of essays, The Collected Schizophrenias, which won the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize and a Whiting Award, warrants much of the hype and anticipation surrounding it. A Granta-anointed Best Young American Novelist for The Border of Paradise (2016), Wang is a highly articulate and graceful essayist, and her insights, in both the clinical and general senses, are exceptional.

Wang’s book isn’t much like the other two. The trajectory of schizoaffective disorder, in its progression, regression, detours, and stubbornness, is a common, looping thread among them, but the way the illness manifests in the three writers is profoundly different. Wang’s voices aren’t much like Schiller’s, and her delusional convictions (for example, that she is dead — also known as the Cotard delusion) are much more unusual. Saks is paranoid and manic while Wang leans to catatonia. Wang’s book is less alarming than the other two, in part because her voice is so measured and intelligent. The fact is, the three women have different illnesses, even though their umbrella diagnosis is the same — schizoaffective disorder varies as much as its patients do.

In addition, while Schiller was largely swallowed by her illness and Saks threw herself passionately into her career, Wang gives the impression of having lived many lives. She started on the Ivy League track, attending Yale (the alma mater of Saks, as well), which was exceedingly unhelpful in managing her burgeoning illness, and then Stanford, which was closer to her family. She was a fashion blogger early in her adult life, and her knowledge of designers and aesthetics is likely to bewilder the average reader. One of the essays is about disguising herself as high-functioning by using visual markers of wellness: beautiful clothes and makeup from Chanel and Tom Ford. Her survival methods are necessarily elastic:

My makeup routine is minimal and consistent. I can dress and daub when psychotic and when not psychotic. I do it with zeal when manic. If I’m depressed, I skip everything but the lipstick. If I skip the lipstick, that means I haven’t even made it to the bathroom mirror.

A sexual assault lies beneath Wang’s daily experience for years, until her illness triggers PTSD, which complicates her treatment plan further. Then, after her physical health declines mysteriously and precipitously, she is diagnosed with late-stage Lyme disease.

Bookstore shelves are crammed with PTSD memoirs, Ivy League reminiscences, fashion world tell-alls, sexual-assault survival stories, and chronicles of fighting against debilitating illness — Wang’s friend Porochista Khakpour even wrote an entire book, Sick, about living with late-stage Lyme disease — but Wang has been inside all of these identities, lived all of these selves and more. Her perspective in The Collected Schizophrenias is encyclopedic and prismatic even without taking into account how her primary mental illness may have fractured her identity.

Wang asks rare, necessary questions about her condition: “What happens if I see my disordered mind as a fundamental part of who I am? It has, in fact, shaped the way I experience life.”

She’s mildly arguing against “person-first language” that “suggests that there is a person in there somewhere without the delusions and the rambling and the catatonia”:

There might be something comforting about the notion that there is, deep down, an impeccable self without disorder, and that if I try hard enough, I can reach that unblemished self. But there may be no impeccable self to reach, and if I continue to struggle toward one, I might go mad in the pursuit.

She writes with clarity about how it feels when a psychotic episode descends upon her, an experience only a fraction of us will ever have. The entire passage, from “Reality, Onscreen,” is two and a half pages of captivating prose, but the conclusion is most gripping:

Something’s wrong; then it is completely wrong […] The moment of shifting from one phase to the other is usually sharp and clear; I turn my head and in a single moment realize that my coworkers have been replaced by robots, or glance at my sewing table as the thought settles over me, fine and gray as soot, that I am dead. In this way I have become, and have remained, delusional for months at a time […] What’s true is whatever I believe, although I know enough to parrot back what I know is supposed to be true: these are real people and not robots; I am alive, not dead. The idea of “believing” something turns porous as I repeat the tenets of reality like a good girl.

These essays are mesmerizing and at times bittersweet — not unlike The Border of Paradise, which is a horrifying family drama written in balletic prose. In other ways, the two books don’t feel very similar, but that’s a mark of Wang’s craftsmanship. Her novel is warmer, with shifting perspectives that dwell on human moments, where her essays are even and controlled. Whenever they feel too icily flawless, though, Wang reveals her sense of humor. When a stranger looks her up and down as she’s in a delusional (but functioning) state, she quips, “Yes, I thought, our eyes meeting, you may think I’m hot, but I’m also a rotting corpse. Sucks to be you, sir.”

Often collections like this gather essays either too independent from one another or too repetitive in their details to form a fully satisfying work. Wang’s book mostly avoids these problems, but it does have a sense of incompleteness, which derives, perhaps, from the sense that the author is leaving things out. It’s not a particularly juicy or grotesque book, and a jaded reader of sensational memoir may find this suspicious. Her book often feels like the equivalent of her makeup routine: she’s passing as a calm, informative writer with a sophisticated prose style when inside her head it’s chaos.

This is not to say it’s a dishonest book, but it does offer up Wang’s best and most beautiful self, for the most part, and only rarely shows her gibbering at the mirror or impassively giving away her possessions. Of course, that is no one’s business but Wang’s. She is not required to expose her interior horrors to the reading public just because other essayists and memoirists do. Besides, if the book seems incomplete, or unfinished, it’s because Wang’s life is, too. Not because her illnesses have lessened her — they certainly have not — but because she is continually evolving, and aware of it. The collection carries a sense of starting over, and over, and over, with each new diagnosis, each new psychotic episode, each new obstacle that Wang must cope with to survive and thrive. Her extraordinary precision as a writer helps her organize and describe the junk drawer of intention and failure and process and truth that is life.

The Collected Schizophrenias is a necessary addition to a relatively small body of literature, but it’s also, quite simply, a pleasure to read. The prose is so beautiful, and the recollection and description so vivid, that even if it were not mostly about an under-examined condition it would be easy to recommend. Esmé Weijun Wang is poised to become a major writer, and this is her origin story.

¤

Katharine Coldiron’s work has appeared in Ms., the Times Literary Supplement, VIDA, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She lives in California and at kcoldiron.com.

The post Fractured Origins in Esmé Weijun Wang’s “The Collected Schizophrenias” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://bit.ly/2UIUcM9

via IFTTT

0 notes

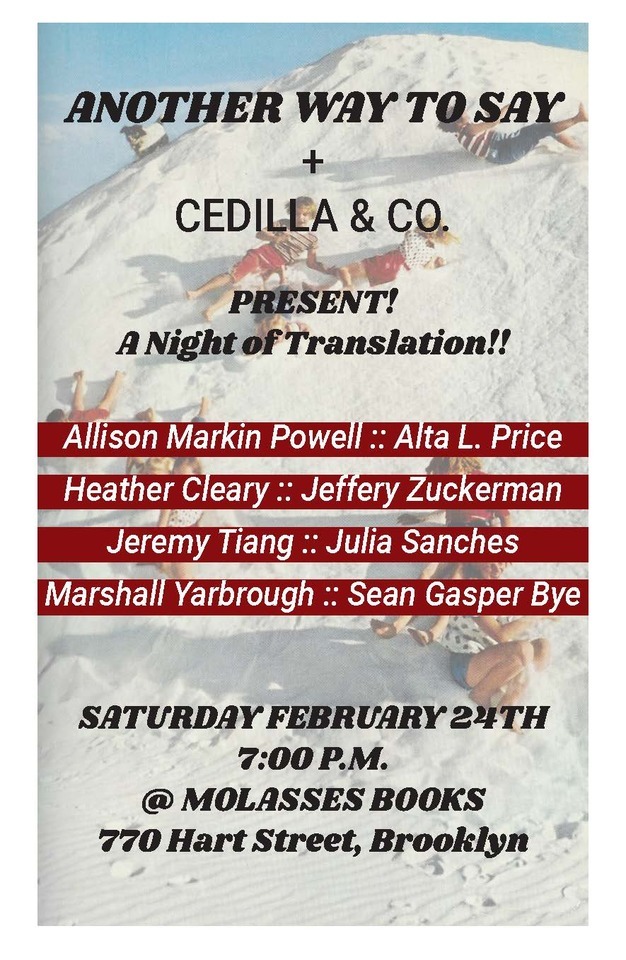

Photo

Join us for a special edition of Another Way to Say with Cedilla & Co., a first-of-its-kind translator collective. Cedilla & Co. is uniquely positioned to speak on the visibility of the translator, our evolving role in the publishing industry and the dynamics particular to our (their) respective languages.

From the Japanese, Italian, German, Spanish, French, Chinese, Portuguese, Catalan and Polish, (re)presenting:

Allison Markin Powell, from the Japanese. Her translation of Hiromi Kawakami’s The Briefcase (Counterpoint) was nominated for the 2012 Man Asian Literary Prize, and the UK edition (Strange Weather in Tokyo, Portobello) was nominated for the 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. Her other translations include books by Osamu Dazai and Fuminori Nakamura. Her work has appeared in Words Without Borders, Monkey Business, Granta.com, and Fifty Storms, among other publications.

Alta L. Price, from the Italian and German. She was awarded the Gutekunst Prize for her translation of Dea Loher’s novel Bugatti Turns Up. Her most recent books include The Dynamic Library (Soberscove, 2015), Jürgen Holstein’s The Book Cover in the Weimar Republic (Taschen, 2015), Corrado Augias’s The Secrets of Italy (Rizzoli Ex Libris, 2014), illustrator Beppe Giacobbe’s Visionary Dictionary (Lazy Dog Press, 2013), and Marco Biraghi’s Project of Crisis (MIT Press, 2013). She is currently vice president of the New York Circle of Translators, and she loves puzzles—translation being her favorite kind.

Heather Cleary, a translator from Spanish and a founding editor of the digital, bilingual Buenos Aires Review. Her translations include Sergio Chejfec’s The Planets (finalist, Best Translated Book Award) and The Dark (nominee, National Translation Award) for Open Letter, and Poems to Read on a Streetcar, a selection of Oliverio Girondo’s poetry published by New Directions (recipient, PEN and Programa SUR grants). She has contributed translations and essays on literature in translation to various anthologies and periodicals. She holds a PhD in Latin American Cultures from Columbia University and teaches at Sarah Lawrence College. She has served on the jury of the BTBA and the PEN Translation Award.

Jeffrey Zuckerman, a translator from French, most recently of Ananda Devi’s Eve Out of Her Ruins (Deep Vellum) and Antoine Volodine’s Radiant Terminus (Open Letter), and he has contributed to The New Republic, The Paris Review Daily, The White Review, and VICE. A graduate of Yale University, he has worked in book publishing, been a judge for the PEN America Translation Prize, and is Digital Editor at Music & Literature Magazine. He is a recipient of a PEN/Heim Translation Fund grant for his ongoing work on the complete stories of Hervé Guibert.

Jeremy Tiang, who has translated more than ten books from Chinese, including novels by Zhang Yueran, Chan Ho-kei, Su Wei-chen and Yeng Pway Ngon. He has been awarded a PEN/Heim Translation Grant, an NEA Literary Translation Fellowship, a Henry Luce Foundation Fellowship, and a People’s Literature Prize Mao-Tai Cup for Translation. Jeremy also writes and translates plays, including A Dream of Red Pavilions (Pan-Asian Rep, New York) and Xu Nuo’s A Son Soon (Manchester Royal Exchange, England). His short story collection It Never Rains on National Day (Epigram Books, 2015) was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize, and his new novel State of Emergency is now out from Epigram Books.

Julia Sanches, a translator of Portuguese, Spanish, French, and Catalan. Her book-length translations are Now and at the Hour of Our Death by Susana Moreira Marques (And Other Stories, 2015) and What are the Blind Men Dreaming? by Noemi Jaffe (Deep Vellum, 2016). Her shorter translations have appeared in Suelta, The Washington Review, Asymptote, Two Lines, Granta, Tin House, Words Without Borders, and Revista Machado, among others.

Marshall Yarbrough, a translator from German. He has translated novels by bestselling authors Marc Elsberg (Blackout, forthcoming from Transworld) and Charlotte Link (The Unknown Guest and The Rose Gardener, Blanvalet, 2014 and 2015 respectively). His translations of work by Anna Katharina Hahn and Wolfram Lotz have appeared at n+1, InTranslation, and in the journal SAND. His critical writing has appeared in Electric Literature, Full-Stop.net, Tiny Mix Tapes, The Rumpus, and The Brooklyn Rail, where he is assistant music editor.

Sean Gasper Bye is a translator of Polish literature. His translations of Watercolours by Lidia Ostałowska (Zubaan Books) and History of a Disappearance by Filip Springer (Restless Books) were published in 2017. His translations of fiction, reportage, and drama have appeared in Words Without Borders, Catapult, Continents, and elsewhere, and he is a winner of the 2016 Asymptote Close Approximations Prize. He studied modern languages at University College London and international studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies. Since 2014, he has been Literature and Humanities Curator at the Polish Cultural Institute New York.

...

Come early to get a book and get a buzz. We'll touch on works-in-progress, underrepresented authors, your burning questions perhaps?

All events are free and open to the public. There is domestic, red and white available to buy/imbibe at Molasses.

Find more re: Cedilla & Co. @ http://www.cedilla.company/

0 notes

Text

GROZ: Truth and beauty - Yale Daily News (blog)

GROZ: Truth and beauty Yale Daily News (blog) Last Friday, I picked up a copy of Rumpus' “50 Most Beautiful” and read it over breakfast. I was initially giddy with excitement — finally I would get to find out who was the fairest of them all! But by the fifth page my building curiosity had ...

0 notes

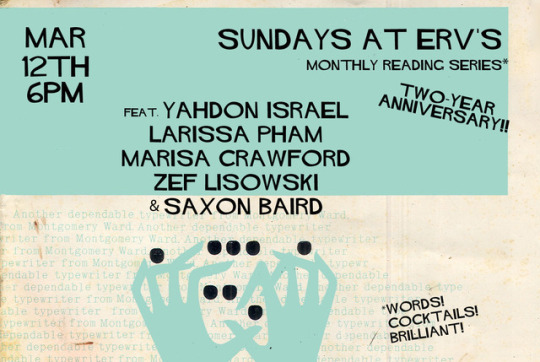

Photo

There's a lot to celebrate this month at Sundays at Erv's! March marks the two-year anniversary of this little reading series, as well as the opening of the new expanded space at Erv's! We've got five stellar readers to present, party hats and other favors, and, as always, Erv's famous cocktails. Join host Madeline Stevens March 12th at 6pm and listen to the literary stylings of fav Erv's alum Yahdon Israel and Zef Lisowski as well as new voices Marisa Crawford, Larissa Pham, and Saxon Baird.

Marisa Crawford is the author of the poetry collections Reversible (2017) and The Haunted House (2010) from Switchback Books, as well as two chapbooks. Her poems, essays, and articles have appeared in publications including Hyperallergic, BUST, Bitch, The Hairpin, and Fanzine, and are forthcoming in Electric Gurlesque (Saturnalia Books, 2017). Marisa is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of the feminist literary/pop culture website Weird Sister. She lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Yahdon Israel is a 26 year-old writer from Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, who writes about race, class, gender and culture in America. He has written for Avidly, The New Inquiry, ESPNW and Brooklyn Magazine. He's a contributing editor at LitHub. He recently graduated with his MFA in Creative Non-Fiction from the New School. He runs a popular Instagram page which promotes literature and fashion under the hashtag Literaryswag. He's the Content and Social Media Director for MakersFinders, a digital platform that connects independent makers to passionate finders through stories. Above all else: he keeps it lit.

Larissa Pham is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Guernica, The Nation, Adult Mag, Nerve, New York Magazine, Maxim, Dazed, Salon, Adbusters, GOOD, The Rumpus, The Hairpin, Gawker, VICE, The Intentional, Packet Bi-Weekly, The Yale Literary Magazine, and elsewhere. She is the author of Fantasian, a New Lovers novella from Badlands Unlimited.

Zef Lisowski a non-binary poet and NYC transplant; their work has been published most recently in Vetch, the journal of trans and genderqueer poetry, but also in Hobart, FreezeRay Poetry, decomP Magazine, and other journals. They are a poetry reader and staffer for Apogee Journal as well.

Saxon Baird has written for Guernica, Slate, Vice Sports, Gothamist, EATER, 3:AM, Fanzine, Blunderbuss, Teen Vogue, Large Up and other places. His also produced numerous radio documentaries for PRI's Peabody-Award winning program Afropop Worldwide. He moonlights as a bartender.

https://www.facebook.com/events/1797081663948076/

0 notes