#that like. biology. right? it has to do with algae? I think?? fascinating little bugs I'm sure

Text

>reads an article about climate change in late antiquity based on a study of downcore fossil dinoflagellate cyst association

>does not undertand a word of the scientific side of said article

>picks up next article on a similar topic

>yeah

#[.txt]#I know what uh. whatever dinoflagellate cysts are they must be very cool and interesting#but all I got from that bit of the study was that they change based on water variables#and that's all I need to know about them. godbless#that like. biology. right? it has to do with algae? I think?? fascinating little bugs I'm sure

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Relationship With Nature

Growing up, I was never a kid who liked to play outside in the dirt. For some odd reason, I had this fear of getting my hands dirty. In addition, I used to be deathly afraid of water, but that's a story for another time. To be completely honest, when I was very young, I never liked being outside. I always preferred to be inside the house playing with toys or doing crafts. I think the amount of bugs in my neighbourhood scared me inside. Each day, my parents would take me on a walk through our neighbourhood and I remember that I would cry and whine the whole time until we returned home. It wasn’t until the beginning of grade 7 when I started to take an interest in science. I remember getting to use my first textbook and thought about how this was a big difference from the previous years work. In previous years, we had just gotten handouts with little readings on them. After flipping through some of the pages in the textbook, I began to think about all of the new topics I was going to learn that year. This was the first time I had heard the words ‘eutrophication,’ ‘abiotic,’ and ‘decomposer.’ I started to think to myself that maybe this would be an area I would be interested in studying one day but at the time high school was right around the corner and I was more worried about that.

When I began secondary school, I decided it would be time to take more of an interest in the STEM education. Each year, I took science as one of my courses, as well as a variety of technology courses. In my freshman year, the technology course allowed us to try every different field of technology that was offered at our school. We got to try a variety of different fields such as welding, machine shop, design, etc. Although I did thoroughly enjoy the wood working class, horticulture was always my favourite strand of technology. I always found that subject very intriguing as there are so many plants, propagation techniques, and landscape methods that we had the chance to learn about. My school even had its own hydroponic system that we grew vegetables in year round. It was here, that I started to really become interested in studying plants and the environment in the future. In my final two years of secondary school, I took a great interest in biology. In grade 12, we completed a 28 day pond study on the body of water behind our school, where we analyzed water samples, looking at pH, algae growth and taking a close look at the microorganisms living in the pond sample. By the end of high school, I knew that I had developed a passion for biology and the environment and knew that I would pursue it in post-secondary school.

Reflecting on what I have just told you, I know that it sounds like I have had a negative relationship with the environment, but I honestly think that it has had a great impact on the growth of my studies. I regret not spending more time outdoors growing up, exploring the woods and being surrounded by mother nature. Over the years, my passion for the outdoors has evolved to the point, that I now find myself outside as much as I possibly can doing various activities whether it be; hiking, skiing, taking my dog for a walk, or even just sitting outside reading a book. I thoroughly enjoy a hike in the Rock Glen Conservation in Guelph every now and then as I find it is a very beautiful place to spend time.

During my time at the University of Guelph, I have taken many biological science courses as I find these topics fascinating and very important to be taught, especially now more than ever. As well, I have been a part of some climate-action protests as it is my goal to educate and empower people with the knowledge I have gained from these courses to better our planet for the future.

When I think about a “sense of place,” my first thought is always my dog Leila. Before I owned a dog, I did not make as much time for activities outside as I do now, but I am glad that I have her now. There are plenty of reasons why I am lucky to have her, but focussing on the topic at hand, I find that having a pet comes with a lot of responsibilities, one being exercise. Taking her for exercise not only benefits her, but it also benefits me too because I get to spend so much time outdoors.

Overall, I think my relationship with nature has evolved to something amazing that I am grateful for every day, especially in a country like Canada, as some people are not as fortunate to live in safe and beautiful conditions.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Cockchafer, Part 2”

*(Featured image by dbgg1979 [CC By 2.0], via Flickr)

By Birgit Müller and Susanne Schmitt

We met Ernst-Gerhard Burmeister at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology where he has dedicated most of his professional life to the amazing collection of over 25 million zoological specimens, one of the largest natural history collections in the world. The collection owns more than 100 000 of the approximately 500 000 species of beetles (Coleoptera) in the world. He has been an active defender of the zoological collection in political committees and has advised the region of Bavaria on issues of biodiversity. He has also traveled extensively, following mayfly swarms (Palingenia longicauda) in Hungary, and exploring the fauna of the Amazon at the border between Peru and Bolivia. When he spoke to us about his experience of insect loss, however, he returned to the calm of the sunny conference room…

The first time I experienced that sudden feeling of loss was about 20 years ago when I could not find any cockchafers in my garden in May. I used to collect them every year for my daughter’s birthday until she was 30 years old. She was born in May and it became a tradition between the two of us that she loved. When she was small, it had been absolutely no problem to find cockchafers in the garden; but then we began to see fewer and fewer of them until, finally, I had to collect them from somewhere else. Fifty years ago cockchafers belonged to spring. It was the creature that reminded us that nature was awakening. But people live so differently nowadays that they don’t even realize the loss. Who still goes for a walk on a calm May night and observes the cockchafers buzzing around the streetlights? Who realizes what the type of agriculture we are practicing does to insects?

A cockchafer in the grass. Photo: Max Pixel (Public domain)

Cockchafers mating. Photo courtesy of Ernst-Gerhard Burmeister.

The use of potent agro-chemical continues unabated. DDT, the chemical Rachel Carson campaigned against so vigorously in 1962, is still permitted in 21 countries in the world. In France, researchers studying the layers of sediment in Lake Saint André in Savoie found the greatest concentration of DDT in sediments dating from the 1990s—that’s 20 years after DDT was banned in France. Neonicotinoids, the world’s most used pesticides, are far more toxic than DDT and have a half-life of up to 20 years in the soil. This means half of all neonicotinoids in the soil are still there 20 years later—and since their use is not forbidden, they have only been accumulating. We see traces of them in wildflowers and future crops.

Neonicotinoids are particularly harmful to many insects and act as nerve agents. Eleven thousand bee swarms have already died from toxic exposure in the Rheinland. While toxicology studies last only two to three days, the consequences of pesticide use affect insects for years. They don’t just fall dead from a stem: they lose their orientation, don’t feed properly any more, lose their capacity to reproduce, and are less resistant to disease and parasites. But if you argue with the chemical industry or farmers, many just laugh their heads off when confronted with your observations of loss and the absence of insects. Only hard data counts. This is why it was so important that the entomologists in Krefeld documented the decrease in the biomass of insects over 25 years. In one site, the biomass of insects collected over one year in 1989 was 1,6 kilograms, compared to only 300 grams of insects left in 2013.

Our nature protection laws don’t do enough to shed light on the issue of insect loss. At most, they suggest that it is important not to disturb animals in their natural environment. While those who love and know nature—and in particular insects—try to interfere with nature as little as possible, other groups continue to do whatever they please: practicing chemical intensive agriculture, or paving over soil. In Bavaria, insect habitats continue to be destroyed. Bavaria is the only federal state in Germany where farmers are not expected to establish a protective agricultural border between farmland and bodies of water.

A strip of wild flowers along a farm track at Langley Park. Photo © Des Blenkinsopp, licensed for reuse (CC BY-SA 2.0), via Geograph.

Although farmers are encouraged to plant strips of meadow flowers between cornfields and the road—called “Akzeptanzstreifen”

(acceptance strips) in German—their main purpose seems to be to make people more accepting of monocultures. These strips do not help insects much; most of them are mowed just when the insects have laid their eggs. It seems that the authorities are more interested in drawing attention to insects by growing and maintaining entomology collections in institutions, rather than by nurturing actual living insects. However, we can only speak with authority against the practices that kill insects if we are able to document what types of insects exist, and where and how they live. We need to learn to pay attention to insects again.

When I was a toddler I was fascinated by everything that crept and fluttered. My father was the son of a forest ranger and he understood my fascination with the natural world, that I needed to touch things in order to understand them. Contrary to other kids my age, and especially the kids today, I was allowed to keep bugs in boxes, dig up maggots, and play in forest swamps. I used all my senses, had to touch everything to examine it, test it and try it out. I liked bugs with stable chitinous armor that were not easily damaged by my handling them. When I became a biology student, I specialized in insects and became fascinated with their capacity to identify and follow smells. Did you know that ants can distinguish left-handed sugar molecules from right-handed ones? It took humans two hundred years to figure that out.

Goliath beetle. Photo by Skyscraper [CC BY 3.0], from Wikimedia Commons.

There is so much to discover. Parents and schoolteachers should let their kids get close to insects and share knowledge about them. If a child knows something, they lose their fear of it, their timidity. They constantly discover new things and learn from them: “Oh these butterfly wings have soft scales, I’d better not touch them.” It is our alienation from insects, being out of touch with them, that makes people in Germany not realize that insects are disappearing.

When I was in East Africa, in Irangi Kenya, the people had names for all kinds of insects and could distinguish them according to their use: as natural predators, as food. I would describe an insect to children there and they would fetch it for me. They knew what kinds of rotten fruit attracted them. Like me when I was small, they played with bugs. I remember they had a giant bug—we called it a Goliath beetle (Goliathus). They would tie it to a string and have it fly around them like a helicopter; and when it got tired, they would let it go.

Here in Germany people think they can lead a sterile life: everything has to be washable. Any apple with a worm in it gets rejected. Everything has to be flawless. They don’t want to share their habitat with small creatures, to feel revulsion because something else is living with them—especially if that something is a creature scuttling out of sight, like a silverfish (Lepisma saccharina) or cockroach (insect of the order Blattodea). If you switch on the light and see something disappear under the cupboard…Uhhh!

Silverfish belong in the bathroom. They are useful there. They eat the algae from the joints of bathroom tiles. Cockroaches rid the kitchen of discarded food where fungi and bacteria might otherwise settle. Kids are not by nature afraid of spiders. Although, even my grandchildren cry when they come to my house: “Uhhh there is a vibrating spider (Pholcida, or cellar spider) up there!” But at least they know it by name.

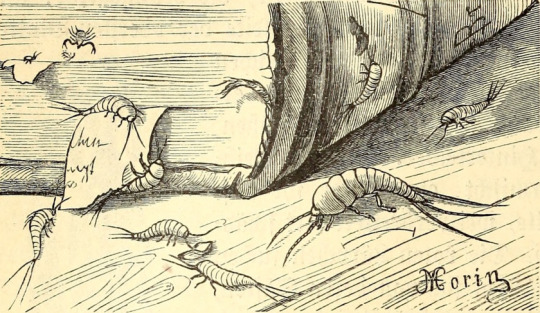

Illustration of silverfish (Lepisma saccharinae) taken from Brehm et al., Brehms Tierleben : allgemeine Kunde des Tierreichs (Wien: Bibliographisches Institut, 1890), 696. Image via Flickr (Public domain).

We have a lot of work ahead of us to counter this tendency. Most of the initiatives to help insects are still limited and voluntary. It is generally private nature protection associations (Naturschutzverbände) that offer courses and excursions for those interested in rediscovering and reconnecting with insects, when the state and the official school system should really be the ones driving these actions. Nevertheless, such initiatives have been quite successful in encouraging the public to engage with their environment: In big supermarkets that sell gardening supplies, glyphosate has been taken off the shelves because of pressure exerted by the customers (although farmers do of course still use large amounts of it on their fields). Hobby gardeners have turned away from fragrance-free flowers and are asking for aromatic plants that will attract insects. Nature protection associations have also encouraged their members to abandon uniform mowed lawns. As a result, we’re now seeing some of the 540 species of solitary bees and bee colonies returning to pollinate flowers and blossoms. These are small beams of hope indeed.

Reflections on Insect Loss “The Cockchafer, Part 2” *(Featured image by dbgg1979 , via Flickr) By Birgit Müller and Susanne Schmitt…

#biodiversity#cockchafer#conservation#DDT#education#entomology#environmental policy#insects#pesticides

0 notes