#i like aquatic macroinvertebrates

Text

There is truly no better feeling than when you get a research grade on iNaturalist

WISH IT WOULD HAPPEN TO MY OBSCURE BUGS AND NOT JUST THE REALLY COOL ANIMALS

#SOBBING IN AQUATIC MACROINVERTEBRATE SPECIALIST#I HAVE SUCH A GOOD PIC OF A PSEPHENINAE BUT NOONE CARES#BUT MY INCREDIBLY BAD PICTURE OF A TRICOLOR BAT GOT VERIFIES TWICE IN LIKE AN HOUR#inaturalist#bats#aquatic macroinvertebrates#bugs

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is your favorite aquatic invertibrate?

THIS is a loaded question. I've kept this in my inbox for a while cause there's SO MANY it's hard to choose. I'm most interested in mollusca and crustacea but those are still large categories.

My favorite mollusk is Dirona albolineata, the frosted alabaster nudibranch. Absolutely gorgeous and come in my favorite color.

I pretty much love all nudibranches though. My second favorite would have to be sea butterflies, they're so weird!

And of course the animal crossing famous Clione limacina or sea angel

Academically, I'm currently researching freshwater mussels for our reintroduction project. Mussels may not be as flashy as nudibranchs, but they are extremely important for improving water quality in freshwater habitats. It's hard to choose a favorite, but one I've researched the most and have grown fondly of is Alasmidonta varicosa, the brook floater. We are hoping to eventually reintroduce it to it's previous native range. Fun fact, when you pick them up out of the water, they stick their "tongue" (foot) out.

I literally had the species name written on my giant whiteboard in the office for a few months so my boss would keep seeing it since I really wanted us to use it as a flagship species to design our reintroduction project around. Fast forward and we've gotten a grant and things are progressing nicely.

Anyway on the crustacea side that's an even harder choice. I'm always excited to see aquatic isopods and scuds. I'm probably most fond of Malacostraca (amphipods, isopods, decapods, etc.) and Branchiopoda (clam, fairy, and tadpole shrimp, and water fleas). Do not make me pick one I am unable to. I will say I have a particular soft spot for crayfish as they are the organisms I've had the most one-on-one time with (I literally have a pet crayfish named Mr Pinchy). I just love anything with pinchers (ʃƪ^3^)≧〔゜゜〕≦

First crayfish I ever held doing it's little defensive stance of Shake Em Like You Just Don't Care. Just take a look at it's mouth! The mouthparts are so cool! I love watching Mr. Pinchy eat.

My favorite macroinvertebrate would hands down be Corydalus, aka Hellgrammites, which are the larval form of Dobsonflies. I have yet to see an adult dobsonfly in person, but have been told they're terrifying and not very nice. We shall see about that. Hellgrammites are simply angry pathetic overdramatic babies and while people say they bite I've held plenty and never been bit. They will absolutely go for the other bugs in the tray so you do have to keep them in a separate container. We've lost a couple of caddisfly larvae to the jaws of the mighty hellgrammite.

Just look at it! Here's a video where I'm trying to get a good shot of it's gills (those frilly things on its underside). They roll into a defensive ball which is so endearing. I also love anything that can curl into a ball. I think they're absolutely adorable but most people tend to disagree with me ಥ‿ಥ

TDLR I love all aquatic invertebrates so very much. I didn't even get into shrimp or coral or starfish! They make me so happy I actually have to limit how much I read about them in a day because my emotions get too big and cause me to become hyper (which is a bad combo for fibromyalgia). I'm not great at remembering information so I get to constantly relearn and rediscover things which is a blessing and a curse. This also makes taxonomy especially hard for me so let me know if I messed up somewhere.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Becoming a Science Educator

An American toad, similar to those found in the author's childhood backyard.

Think back to when you were a child - what was your favorite way to learn how something works? Mine was to ask loads of questions and then jump in and get my hands dirty. I specifically remember catching toads in the backyard with my mom, asking questions about their appearance and where they lived. She would tell me about the myth of them giving you warts, that they might pee on your hand if they were scared, and how to hold them gently and then let them go. Twenty years later, I became a research ecologist studying amphibian diseases, and I learned how to sharpen these inclinations into more robust skills: how to create focused questions and experiments, collect and analyze data, and present the findings to a range of audiences.

Today, I teach and design curriculum for home-school and summer camp programs at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Fostering the learners’ own questions and devising hands-on ways to investigate them is the focus of my work. Science and nature provide unlimited opportunities for first-hand investigations, and the process of metamorphosis is one of my favorite examples.

An 8-year-old camper has likely learned about butterfly metamorphosis in school, and might be able to name the four stages: egg, caterpillar, pupa, and adult. Scientists call this four-stage process “complete metamorphosis,” a term whose qualifier invites one to wonder, “what is incomplete metamorphosis?” Enter the majestic dragonfly. Dragonflies also go through metamorphosis, but with only three stages: egg, nymph, and adult; their transformation is therefore termed “incomplete.” Noting this small difference suggests another question: what else is different about a dragonfly?

Above and below: Dragonfly nymphs collected and released in a Pittsburgh section of the Ohio River.

Well those first two stages - eggs and nymphs - are in water! That is why they are part of the far larger group of aquatic macroinvertebrates, creatures with no backbone that can be seen without magnification and that live at least part of their life in water. Some dragonfly nymphs are impressive predators and can live for years in this aquatic phase, even though their adult lives last only a few weeks. In what ways, I challenge the 8-year-olds, is this transformation similar or different from that of a caterpillar and a butterfly?

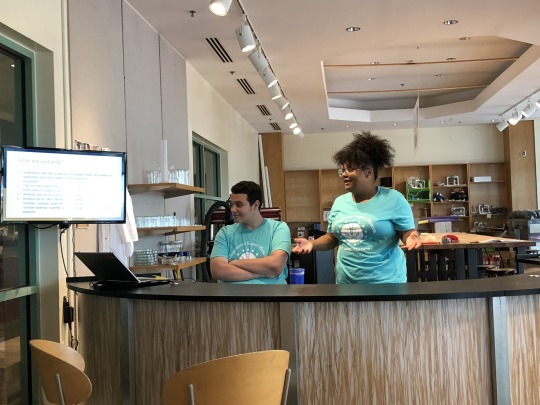

Jenise looking through a stream water sample for aquatic macroinvertebrates in a sorting tray.

After we’ve explored these questions, we make a trip behind the scenes to look at some insect specimens up close, and allow the students to directly ask the museum’s research scientists even more questions. Finally, we visit Powdermill Nature Reserve to get our hands muddy by looking for dragonfly nymphs and other aquatic macroinvertebrates in the research station’s namesake stream. And before we know it, we’ve done actual science: used the scientific method to gain understanding about the world around us!

I came to teaching from research science because I love building interactive experiences of the world around us like these into courses that can educate and inspire young people. This type of scientific inquiry is universal, and these practices can be adjusted for age. A class about dragonflies for a 12-year-old group, for example, might focus on data collection and include the presentation of our findings to the younger campers. Whatever the age level though...I get to get my hands dirty.

Jenise Brown is a Museum Educator with Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Science Education#Science Educator#STEM#STEAM#Science Camps#Powdermill Nature Reserve

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I mentioned in my previous post that I would be interested in modifying the current way fish species are described. I’ve been looking into that a bit, and while modern descriptions do often include some notes about the habitat or other fishes, they are still missing some of the information I’d like to see, some of which would be very easy to collect.

My ideal species description would include:

All requisite description material for the delineation of the new species, i.e. morphological description, any genetics research conducted, comparisons to relatives, etc.

Habitat parameters: pH, DO, salinity (where applicable), TDS, flow rate, depth, etc.

Habitat description, ex: dark blackwater with little flow,, heavily shaded by surrounding vegetation, located in [geology descr.]

Other fish species captured during sampling when holotype was collected

Sampling of macroinvertebrates and plankton communities, with representative taxa listed (note that these are not only relevant to possible food options but also are indicators of water quality)

identification of aquatic and riparian plant species at collection site (but if no ID, at least mention them in the habitat description)

any other relevant notes about nearby area, ex: near town with agricultural runoff

any other nonfish animal species observed in the habitat during sampling, i.e herpetofauna, birds

Provided you don’t have time/funding limits preventing the collection of this data, and have reasonable knowledge of the other taxa found in the region to be able to identify them to a useful taxonomic level (doesn’t have to be very specific in some taxa - macros are often ID’d to order or family, IDing them even to genus is a rare skill), most of these should be fairly reasonable things to test or make note of during your initial sampling for fishes.

Particularly water parameters - I can’t imagine why those aren’t already measured every time sampling is conducted. If a research institute invests in a probe and maintains it well, most of these readings can be taken with a quick digital measurement that takes no time or exceptional effort.

Sampling other taxa is pretty time consuming, so that’s the one on this list most likely to be cut by restraints, but I think its important enough to include where possible because understanding the community a species exists in is much more valuable to any future uses of the research.

As I mentioned in the notes of the previous post, while I could see some possible resistance to including this information because science likes to be concise and this isn’t necessary for delineating species, I think broadening the scope of the information included alongside the species description can only make the research more useful not only for future studies, but for everything research gets used for outside of the sciences. Governments, companies, individual citizens...research is for everyone’s benefit, and species descriptions would be both more useful and more accessible if they included at least some of this information.

But anyways, I am curious what else anyone would like to see in a species description?

Anything that would require significantly more, involved research would be unlikely to make it in to such a revision of the species description format, since those basically require their own studies and so are better treated as their own research. But if it takes only a reasonable amount of effort to collect the extra information, why not include it?

#i asked this in the last post#but thought it wouldnt be likely to get as many replies hidden in a big long ramble aboutother stuff#so i made it its own post

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ripple Effects of Biodiversity at Yellowstone, Contamination of the Hudson River (Class 2)

Biodiversity is the prerequisite for all ecological processes, functions, and cycles. The textbook readings for this week take the natural environment out of the static state of which we view it day-to-day, and emphasize nature as a process constantly in motion, taking in energy and cycling it throughout the ecosystem throughout multiple scales. The textbook also emphasizes the dramatic disturbances anthropogenic influences cause, inhibiting ecosystem functions and destabilizing delicate natural cycles. It is no secret that our unsustainable land-use habits, pollution of entire hydrological systems, and the wiping out of entire species degrades our environment with near impunity.

Our current environmental epoch is sometimes dubbed the Sixth Extinction–– entailing the eradication of animal species that we may not even realize exist. The wiping out of one species has effects on the entire ecology of ecosystems, this is especially true when keystone species disappear. As evidenced in “How Wolves Change Rivers,” the seventy year absence of wolves as a keystone species in Yellowstone National Park created profound ripple effects in the park’s ecology in the short amount of time they were gone. The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park generated remarkable change in a fraction of the time they were gone, culminating in a remarkable case study on the significant chains of ecological relationships, functions, processes, and cycles that keystone species, like wolves, hold together. When wolves disappeared from Yellowstone in the early twentieth century, unsurprisingly, the population of deer in the park skyrocketed. Deer constantly graze upon vegetation in the ecosystems they inhabit, an increased population of deer in the park meant more deer grazing upon the park’s vegetation–– they grazed so much so that vegetation in the park’s gorges and valleys became scarce. While the wolves did, of course, hunt some of the deer, more significantly, their presence changed the deer population’s behavior, making them averse to the gorges and valleys they once feasted on with impunity where they could be easily spotted and hunted. In under a decade many of the valleys and gorges reforested on their own without deer constantly grazing upon them. Consequently, more birds nested in the park, beavers returned and created dams which conversely created niches for otters, frogs, ducks, among others, which in turn attracted other species, and the feedback loop goes on. The reintroduction of wolves, as the title suggests, indirectly changed the course of the park’s rivers. The new self-seeded forests stabilized the riverbanks, providing them with more stability and also reduced soil erosion. Wolves reclaimed their position as a major hinge upon which the ecosystem balances.

“How Wolves Change Rivers” shows us how ecosystems are composed of networks of relationships that are all connected to each other, and are therefore, highly sensitive to change. The authors of Living in the Environment emphasize this point across multiple scales, from the erosion of kelp forests due to pesticide and herbicide runoff, to the proliferation of microplastics across aquatic food chains and ecosystems.

I find the case of microplastic proliferation most interesting because it provides seamless visualization of our environment as a socio-ecological system and allows us to take into perspective the impact of individual plastic use across multiple scales–– specifically, how the plastic we dispose of reintroduces itself into our lives through the presence of microplastics in much of the seafood we eat. I appreciate the author’s multiscalar approach in regards to plastic production, consumption, and disposal. Specifically the authors show readers how the purchase and consumption of plastic products in our day-to-day lives is against a backdrop of decades worth of damage to marine ecosystems, evident as traces of microplastics appear in a multitude of foods we eat with unknown consequences for public health.

The Hudson River offers a case study that echoes the presence of microplastics across the ecosystem and up the food chain. Although the health of the Hudson River in and around New York City has improved substantially over the past couple of decades, up the river north of Albany, the Hudson is a superfund site contaminated with PCBs from manufacturing industries, notably from General Electric, which dumped their chemical byproducts into the river. When General Electric and other manufacturers dumped PCBs into the Hudson River, they caused a chain reaction through the aquatic ecosystem’s food chain. The chemicals dumped into the river settled at the bottom of the river, macroinvertebrates such as crabs and clams thereby ingest the chemicals, the fish that prey on them vicariously ingest them as well and so do the mammals which eat them, such as many bird species. PCB contaminants subsequently present in mammal waste, contaminate soil, and feed back into the river. Consuming fish from the Hudson River is considered extremely dangerous as there are no safe levels of PCB one can have in their bodies. Ridding the Hudson River ecosystem of PCB contaminants requires extensive river dredging projects which costs not only exorbitant lengths of time, but huge expenditures on part of the government agencies involved. As a result, dredging the Hudson River took nearly two decades, and at least five years of ecosystem monitoring is required to assess its effectiveness.

In conclusion, the Hudson River dredging project and the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park shows the good humans can affect in the natural environment. Plastic pollution, however, will be a long-lived symbol of our environmental recklessness, naivete, and disregard for the health and wellbeing of all living creatures. When much of the upper Hudson River was designated as a superfund site, public education as to the dangers of consuming freshwater fish was urgent, and the public still heed these warnings today. I wonder if in a few years we will issue similar warnings for microplastic contamination of living organisms. Although the conclusion dredging in the Hudson River and methods for cleaning, reducing, and eliminating plastic waste are promising, my question is: Are the feedback loops we destabilized, and the new ones we created too far gone for climate mitigation to deal with?

0 notes

Text

one kiddie pool (or several, it’s more fun)… possibly formerly used as dog baths, duck pools, or for actual kids. Stock tanks (either the tall kind for horses or the short kind for sheep and overheated sheepdogs), horse feed tubs (the black rubber kind) or other small containers. Those saucers you put under plant pots make nice bird baths. Throw in an SAV or two, or a hyacinth.

water hyacinth (don’t let it get loose if you live in the south, where it’s an invasive)… blooms big purple flowers

arrow root

SAV (oxygenators or submerged aquatic vegetation), they keep the water cleaner, add oxygen (good if raising tadpoles) and bloom tiny cute flowers

couple bags o play sand (stupid cheap)

hose, water

optional lotus. Can be started from seeds, then placed in sandy soil in pot. You need to feed them with pond plant fertilizer. They will grow like mad and eventually bloom. You must winter them inside if your pot is small or shallow enough to freeze.

You can set your pools right on the ground, or dig a hole and sink them. Nice for stuff you don’t want to freeze. Or just drain tubs in fall and replant each spring. Replanting means throwing in a couple new hyacinths and SAVs. I kept the SAVs in a bucket in a lightly heated sunroom over winter. They seem fine. I tried to keep the hyacinths in, but they are tricky. Also they are cheap to buy next year. And grow fast. But mine produced a few bulbs that are now in a pool and growing…

A pond deep enough to not freeze can support goldfish (you’d be surprised how big those “feeder fish” or “I won a goldfish” fish get to be in enough water). It’ll also support tadpoles. Toads don’t need a major water source nearby, they’re better adapted to land, so when they metamorphose from tadpole to toad, they’ll just hop out and continue living in your garden. Frogs prefer a bit more water. Those critters may attract the attention of screech owls or great blue herons.

Macroinvertebrates are fun to find in natural water sources like ponds or streams or lake edges. Dragonfly nymphs and other tiny wildlife can be scooped with a net, placed in a shallow white tray (like a frisbee) and photographed. They might like your pond.

https://www.swordwhale.com/planet-water.html

Bonus: pools kill grass so less to mow.

chair with beach

mermaid and kiddie pool garden

water hyacinth

water hyacinth

arrow root and hyacinth

SAV blooming

hyacinth pond

water hyacinth

hyacinth mermaid

lotus pot

lotus pot

lotus effect (sheds water)

American lotus bloom, Sassafras River

argiopes

pollinators

pollinators

tree frog

use your beach for tracking

add some shells

wiggle your toes

do a zen garden

a big enough pond and you can sail

SAV blooms

native hibiscus

hibiscus

water may attract visitors, especially if you add fish

frogs

tadpool

tadpoles in tadpool

hyacinth

hyacinth

hyacinth

mermaids among the hyacinths

Toothless on lotus

macroinvertebrates may come to live in your pond

dragonflies lay eggs in water

American toad

toadlings

toadling

toadling

If you missed Black Panther… this is the “I never freeze” scene…

stuff in a pool (how to make your own beach) one kiddie pool (or several, it's more fun)... possibly formerly used as dog baths, duck pools, or for actual kids.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 12

Alex Heilman

Prof. Van Buren

Intro to Environmental Studies

Water; Our Most Precious Resource

Water is what we need to survive, and we are beginning to put our supply of it at risk. Our bodies are made up of mostly water, 71 percent of our earth is covered in it and it is an essential component of everyday activities. Humans have developed ways to use water as a source of energy and it helps to support the lives of millions of people all over the world. Water is used to generate electricity and it can be rerouted to dry areas to sustain life. We can get water from rivers, ponds, lakes, streams and reservoirs, but we can also get it by extracting it from the ground. The rate at which groundwater is being extracted from our planet has increased to support so many different things. Groundwater can provide drinking water for humans, animals and plants and can also be used for chores in the house like doing laundry or washing dishes. In some places, groundwater reserves are being decimated and some are dangerously close to completely drying out. As the book says, we must manage the supply of water that we have in a more sustainable way. The water that is available for drinking represents a very small portion of the total amount of water on our planet and we are at risk of making it an even scarcer resource. The book also says waters importance is larger than we may perceive. They state that water is an issue involving global health, economies, national and global security and the environment. We must cherish our supply of water and develop new methods of taking care of it.

Water pollution is increasing all over the world in both fresh and salt water systems and if we do not enforce strict policies, we will see irreversible damages. The book defines water pollution as, “any change in water quality that can harm living organisms or make the water unfit for human uses such irrigation and recreation. It usually involves contamination by one or more chemicals or excessive heat or thermal pollution.” [“Miller, G. Tyler, and Scott Spoolman.”] Water can be polluted through a variety of ways that include the dumping of waste or trash, runoff that picks up harmful chemicals and other substances and even through the agricultural industry. River pollution is mainly from the dumping of waste from companies and the runoff from either fields, streets or recreation areas. Ponds and lakes are polluted mainly through runoff of the surrounding areas which usually contains harmful chemicals from trash, fertilizer and other chemicals used to treat grass and other plants. These chemicals can destroy or severely harm entire eco-systems and populations of fish and plants. Chemicals can also cause algae and other invasive species to grow which can block out sunlight and overcrowd ponds and lakes. When the sunlight is blocked, organisms that live and grow at the bottom of lakes and ponds can be severely affected and may even be wiped out. Fresh water pollution is so harmful because there really is not that much of it on our planet although it does go through the water cycle and regenerate itself. The effects it has on the organisms that call fresh water bodies their home is long lasting and can completely change the eco-system, biodiversity, cycle of life and food chain of any given river, pond or lake.

The case study involving the Colorado river from the book goes to show how humans have impacted a natural water source in order to sustain life in places where water is not plentiful. If it weren’t for the dams built along the Colorado river life would not exist, the way it does now in places like Las Vegas and Los Angeles. The Colorado river provides drinking water and energy to millions of people in the mountain states and allows for the growing of crops in places that should be covered in cacti. Because of our greed and increased expansion and industrialization we are changing the entire eco-system of the Colorado river and we are putting its entire existence at risk.

Pollution of our oceans has garnered a lot of media attention in recent years and I believe people are becoming more and more aware of how dire the situation is in lots of places. Some parts of our ocean are covered in garbage that is dumped by people or carried there by runoff. Other pollutants like chemicals from farming and waste from manufacturing plants find their way to the ocean and do massive amounts of damage. In Florida last year there was a massive red tide algae bloom that occurred when runoff carried harmful chemicals and pesticides into the gulf coast that allowed for the growth of toxic algae. When there is enough of these algae it can greatly affect marine life and in Florida it killed thousands of fish, over 150 dolphins and several other species. Another danger that comes with this red toxic algae is that it can release toxins in the air when it is broken up by wave action and this can be harmful to humans' respiratory systems. This outbreak was not confined to one area of Florida but rather the effects were felt up and down the western coast of the state. New regulations and policies must be implemented to control the amount of waste a company produces, and guidelines should be put in place to ensure waste is disposed of properly. If a company or an individual is found in violation of any laws or regulations, they should be fined heavily to limit the chance of it occurring again, although that is easier said than done.

We must tackle the issue of dumping garbage into the oceans and find ways to clean up affected areas. Ocean garbage is affecting marine life all over the world and it also has the potential to affect human health and economic sectors that rely on the ocean. When marine life is exposed to garbage, specifically plastic, they are at high risk of ingesting it and most do end up ingesting some form of garbage. Say a small fish ingests plastic and then that fish is eaten by another fish, like cod, the plastic is then transferred to the cod that ate the bait fish and the cycle continues. Humans like to eat cod and if that cod has plastic inside its body then the person who eats that fish is also ingesting plastic. Most plastic found in marine life is known as microplastics which are very small particles of plastic that end up in various parts of the animal from the digestive tissues to the liver. Cleanup efforts have begun in our oceans, but it is going to take a very long time to pick up all the garbage that now calls the ocean home.

The research I decided to do last summer for the urban ecology research project was based around the effects of runoff on urban ponds. I studied ponds in both Prospect Park and Greenwood cemetery and found that the closer a pond was to a roadway, the more likely it was to be polluted. I led a team of high school students to conduct various water tests to determine the amount of pollution that was present in different ponds. We performed water quality tests, tested for the presence of chemicals and pesticides and logged the populations of different macroinvertebrates. By using all this data, we were able to determine which ponds were most affected by runoff. Another student conducted her research on the microplastics in ponds in both Prospect Park and Greenwood cemetery. The results she gathered were pretty shocking because nearly every macroinvertebrate or other type of aquatic life that she tested had some level of microplastics present in their body. It goes to show that aquatic life is being severely affected by pollution in big and small bodies of water.

Water is what we need to survive but the way in which we are treating it and handling the supply that we have doesn’t reflect that. Massive amounts of water are used for the agriculture industry all over the world and the amount of water we use for this industry is one hundred times more than what we use for personal use. We also need to reduce the amount of pollution we create and come up with more efficient ways to get rid of waste. Less harmful farming and lawn care methods must also be developed to limit the amount of harmful chemicals collected by run off. All in all, we just need to do a lot better when it comes to the caring, using and maintaining our water here on earth.

Word Count: 1,451

Question: What are the necessary steps for implementing harsh restrictions and penalties on companies and individuals who pollute? Is it a realistic idea?

Works Cited

Miller, G. Tyler, and Scott Spoolman. Living in the Environment. National Geographic Learning/Cengage Learning, 2018.

0 notes

Text

Work Week One...Done!

This week was the Ambassadors first work week at the Seaport!

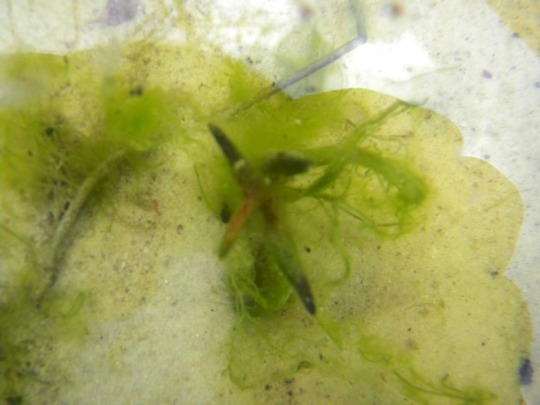

When they weren’t teaching museum visitors about plankton communities or the effects of carbon dioxide on our waterways, they were learning about raptors/birds of prey, taking care of our mussels and floating wetlands, identifying macroinvertebrates in our basin, and recording observations in their field journals.

Two of our Ambassadors, Kyla and Emmanuel, were also tasked with creating their first tumblr post. To hear more about their experiences this week, read below!

“Hi! My name is Kyla, and this is my first year as a River Ambassador. So far, I have learned how to dissect a fish, a frog, and an owl pellet. I also learned about aquatic acidification and the plankton community. One of the things I really enjoyed this week was dissecting an owl pellet, because you can find different types of bones in the pellet. The pellet is created by the owl’s two-chambered stomach...”

“...The first chamber breaks down the food that can be digested, just like ours does. The owl swallows rocks, which allows the second chamber to grind down the animal bones and fur, using its muscles to break down whatever nutrition is left. I also learned what a raptor is, which is a large bird that hunts and kills smaller animals for food. Raptors have important roles in the environment but face many threats and problems because of human threats or lead poisoning. The benefits of having raptors are that they reduce pests in the environment and help control disease.”

Throughout the week, the Ambassadors taught audiences of all sizes and ages, ranging from our summer campers to families from New Jersey, Washington, and of course, Philly. Though Kyla loved learning about owl pellet dissections, Emmanuel found himself enjoying engaging with our visitors.

“Hi! My name is Emmanuel, and this was my first week working at the Seaport Museum. We’ve done lots of fun things so far, like fishing, dissecting, rowing boats, and many experiments. I think my favorite thing to do here are the experiments and presentations. Our “Aquatic Acidification” experiment is my favorite--it helps people learn more about the ways humans’ carbon footprints affect the oceans and rivers. It’s a great feeling to be teaching kids about protecting and saving their water and planet. I love showing them creative experiments to light up their eyes and get them thinking.”

If you’re interested in hearing more about the Ambassadors’ summer or would like to participate in some of their events, feel free to check out their Seaport webpage (http://phillyseaport.org/riverambassadors) or explore the other pages on our tumblr!

0 notes

Text

Learning to See, Seeing to Learn, Freshwater Insects

https://carnegiemnh.org/educator/educator-loan-collection/

The Atlas of Common Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Eastern North America is an online guide and accompanying set of teaching and learning resources designed to support water quality monitoring in citizen science projects and fresh water ecology education.

A suite of visual resources developed to help learners to identify fresh water insects.

For the team of entomologists, learning scientists, software engineers and designers who collaborated in the National Science Foundation-supported effort to plan, develop, test, and revise the site, six words guided the key design goals for this educational resource—Learning to See, Seeing to Learn. Team members aimed both to support the development of observational skills and provide the rich visual resources needed for observation and identification.

In freshwater environments the term macroinvertebrates refers to animals without backbones that can be seen with the naked eye. Because these insects, crustaceans, worms, and mollusks fill vital roles in aquatic food webs, their presence, absence, abundance, and diversity is key to assessing water quality in streams and freshwater bodies over time.

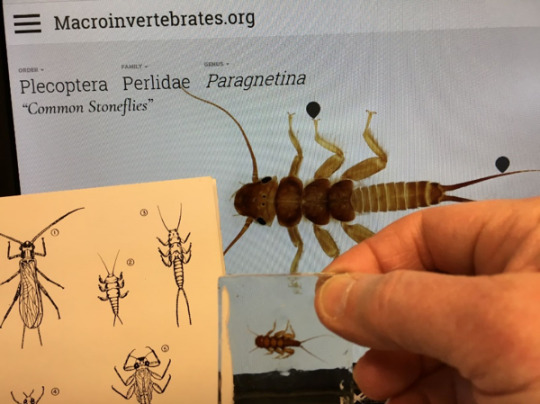

In early April, I spent several hours demonstrating www.macroinvertebrates.org at a table display during the Creek Connections Student Research Symposium held at the Campus Center of Allegheny College. The Meadville college has been providing opportunities for students to become stream researchers for more than 20 years, so I was confident the website would be well received by these budding young freshwater scientists.

The table displayed two iPads for visitors to explore the Macroinvertebrates.org site, a set of stream insects embedded in Lucite cubes, a traditional Riker mount of pond macros, a field microscope, and a stack of promotional postcards.

During the event I spoke with and handed-out information to approximately 100 people, a mix of middle school and high school students presenting their stream study projects, their teachers, Allegheny College students and faculty, and representatives from other organizations participating in the symposium.

Images showing dynamic zoomed and full-scale views of a caddisfly.

Table visitors were particularly impressed by set-ups on the paired iPads -- one screen fully zoomed-in on the abstract art-like image on the “setal fan on a proleg” of a net-spinning caddisfly, the other featuring a whole-body image of the tiny beast. The companion images addressed the linked challenge of learning to see and seeing to learn.

As teachers continue to experiment with ways for their students to use the online guide, the museum has added a set of preserved macroinvertebrates to the Educator Loan Collection. Pictured above is a stonefly embedded in a block of clear resin, and the colorfully-illustrated toolbox that contains a set of ten different specimens prepared in the same manner.

Partners involved in the development of www.macroinvertebrates.org include Carnegie Mellon University’s Human Computer Interaction Institute, University of Pittsburgh’s Learning Research & Development Center, Stroud Water Research Center, Clemson University, and Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Macroinvertebrates#Freshwater macroinvertebrates#Caddisfly#Carnegie Mellon#University of Pittsburgh#Stroud Water Research Center#Clemson University

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snowflakes and Snow Fleas

by John Wenzel

When Shakespeare wrote “Now is the winter of our discontent,” he certainly was not referring to entomologists. Botanists, mammalogists, ornithologists, and herpetologists spend most of the winter in the office waiting for spring. But many entomologists remain busy because insects that live under water go into high gear and treat the winter as their growing season. Hatching from eggs in spring or summer, these aquatic “macroinvertebrates” get their Thanksgiving dinner as the leaves fall into the stream. The insects are grazing and hunting underwater, growing to adulthood, preparing to fly away next spring when the air is warm again.

I was lucky to grow up with a 10 acre woodlot on one side of our house and a 12 acre pond on the other. As a kid, I loved to be out in my row boat or exploring the woods, hunting wildlife, catch and release. My parents encouraged my interests in nature, providing books and equipment that allowed me to increase my knowledge and experience as I grew.

I raised caterpillars through metamorphosis, marked turtles that I would find again years later, and nursed orphaned baby animals. Initially, I had no special preferences other than those that seem to come naturally to all humans. Mammals capture our affection, we all wish we could fly like birds, predators are particularly interesting, as is anything colorful or rare. By the time I was in college, I decided to study insects as a career for many reasons, and chief among them was a very pragmatic element for a striving academic: if you know about insects, you can find fascinating species in your backyard, wherever you live, anywhere in the world.

Since college, I have learned a great deal about many other groups, but when winter is approaching, I enjoy very much being an entomologist. Even on the coldest day in January, I can go out to a stream and find abundant insects doing their thing, below the ice in the cold water. Some specifically emerge in winter when there are no predators around. At Powdermill Nature Reserve, we have plenty of wonderful winter insects, and it is great fun to hunt for these gems.

Here you see a female Boreus scorpionfly who came up from a patch of moss to walk across the snow looking for a male in late December. Also called a snow flea, Boreus is so rare that few entomologists ever see them alive. There is a deep reward in learning to appreciate small things, and I have never regretted becoming an entomologist, especially as winter approaches.

Want to know more about winter bugs? Read about the first Powdermill Christmas Bug Count.

John Wenzel is the Director at Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s environmental research center. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Powdermill Nature Reserve#Snow#Snow Fleas#Winter Bugs#Insects#Entomology#Winter

38 notes

·

View notes