#and the art follows the same pattern. it's simple; thematic; emotive

Text

hello everyone! a quick break from your scheduled art posting to talk about this incredible fic i think ever bloodweave enjoyer should read.

i know it'a already very popular, but imo it's a must-read. i could not praise this fic enough for what it is, the amazing ideas it brings to the table, the incredible execution of the timeloop trope. it's by far the fic i look forward to seeing in my inbox the most (not that other fics aren't absolutely gorgeous), because every chapter is just. a delight to read. it's got angst, fluff, and an amazing romance, but the plot is what really makes it stand out. it's tight, packed with great characterisation and has perfect pacing. please give it a shot if that sounds at all interesting to you. oh yeah, and did i mention that it's got art for every single chapter? yeah, read it. bask in its genius.

#pythoria.txt#turn on the laugh track#if anyone who follows me is already reading it don't hesitate to message me i'm in love with it and could sing its praises all day long#i also think it's a great experience to read it as it updates and the wait between each update is almost part of the experience#because you never know what will happen next and thinking about every chapter for a few days and letting it sit and marinate is the BEST#i'm ngl if this was pay-to-read i would not hesitate. every chapter could be behind a paywall and i almost wish they were just so i could#support the author and show them how much better they make my day with more than just positive comments#luckily for everyone it's free and an absolute joy to read#binge it or read one chapter at a time and let the story sit in your brain#to me this is a fantastic example of how you can sometimes tell a story better with fewer words#nothing about this fic is superfluous#a perfect example of efficiency in writing and how 2 sentences can sometimes wreck you harder than thousands of words#and the art follows the same pattern. it's simple; thematic; emotive#it's beautifully done without being perfect realistic renders. it's BETTER for it even.#it's got great composition and unbelievably touching facial expressions and poses#i just think. the person who created this fic is a bottomless well of talent and creativity. it is GENUINELY fantastic in every way

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

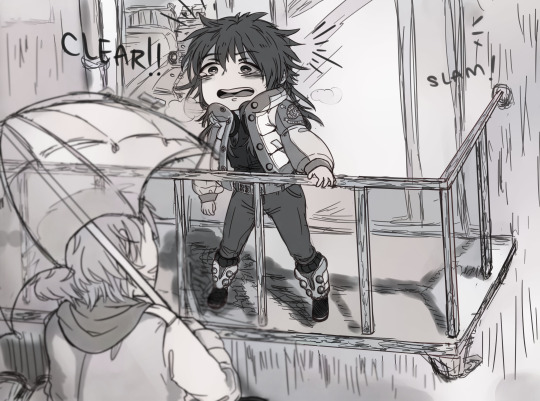

“I heard your voice, so I came... Aoba-san.”

Hooo-boy, if that doesn’t get me emotional every single time. Call it my bias for eccentric bundles of sunshine and softness, or my crippling weakness for the secretly-handsome-and-devastatingly-earnest type, but you can’t change my mind: Clear is, hands down, DMMD’s best love interest. Character development-wise, thematically, romantically, he nails every trial thrown at him, gets his man, and proceeds to break your heart in the tenderest, sincerest way possible. I am hopping with Huge Fan Energy, so this post is gonna be unapologetically long and self-indulgent and grossly enthusiastic. Yeeeee.

————

Look, DMMD meta analysis has been done to death, I get it. This game is old. But I think it stands as testament to its excellent production that it’s still a game worth revisiting years later — especially during these times when social contact is so hard pressed to come by and we all rabidly devour digital media like a horde of screeching feral gremlins. (Have you seen Netflix’s stock value now? The exploding MMO server populations? Astonishing.) It’s pure, simple human nature to want to connect, to cling to members of our network out of biological imperative and our psychological dependency on each other. As cold and primitive at that sounds, social contact also fulfills us on a higher level: the community is always stronger than the individual; genuine trust begets a mutually supportive relationship of exchange and evolution. People learn from each other, and grow into stronger, wiser, better versions of themselves.

Yeah, I’m being deliberately obtuse about this. Of course I’m talking about Clear. Clear, who is a robot. Clear, who is nearly childlike in his insatiable curiosity regarding the human condition.

And it’s a classic literary tactic, using non-human entities to question the intangible constructs of a concept like ‘humanity’ — think Frankenstein, or Tokyo Ghoul, or Detroit: Become Human, among so, so many works in various media — all tackling that question from countless angles, all with varying measures of success. What does it mean to be human? To be good? Who are we, and where do we stand in the grand scheme of things? Is there even a scheme to follow? … Wait, what?

Jokes aside, there are so many ways that the whole approaching-human-yet-not-quite-there schtick can be abused into edgy, joyless existential griping. Nothing wrong with that if it’s what you’re looking for, except that we’re talking about a boys’ love game here. But DMMD neatly, sweetly side steps that particular wrinkle, giving us a wonderfully grounded character to work with as a result.

Character Design — a see-through secret

Let’s start small: Clear’s design and premise. Unlike so many other lost, clueless robo-lambs across media, Clear does have a small guiding presence early on in his life. It takes the form of his grandfather, who teaches Clear about the world while also sheltering him from his origins. It means he learns enough to blend sufficiently into society; it also means that Clear has even more questions that sprout from his limited understanding of the world.

Told that he must never remove his mask lest he expose his identity as a non-human, Clear’s perpetual fear of rejection for what he is drives much of his eccentricity and challenges him throughout much of his route. As for the player, the mystery of what lies underneath his mask is a carrot that the writers get to dangle until the peak moment of emotional payoff. Even if it’s not hard to guess that there’s probably a hottie of legendary proportions stuck under there, there’s still significance in waiting for that good moment to happen. And when it does, it feels great.

His upbringing contextualizes and affirms his odd choice of fashion: deliberately generic, bashfully covered from the public eye, and colored nearly in pure white - the quintessential signal of a blank slate, of innocence. Contrasted with the rest of DMMD’s flashy, colorful crew, Clear is probably the most difficult to read on a superficial scale, not falling into the fiery, bare-chest sex appeal of a womanizer, or the techno-nerd rebel aesthetic that Noiz somehow rocks. Goofy weirdo? Possibly a serial killer? Honestly, both seem plausible at the start.

And that’s the funny thing, because as damn hard as he tries to physically cover himself up from society, Clear is irrepressibly true to his name: transparent to a fault. He’s a walking, talking contradiction, and it’s not hard to realize that this mysterious, masked stranger… is really just an open book. By far the most effusive and straightforward of the entire cast, his actions are wildly unconventional and sometimes wholly inexplicable. But given time to explain himself, he is always, always sincere in his intentions — and unlike the rest of the love interests, naturally inclined to offer bits of himself to Aoba. It doesn’t take the entire character arc to figure out his big, bad secret — our main character gets an inkling about halfway through his route — and what’s even better is that he embraces it, understanding that his abilities also allow him to protect what he cherishes: Aoba.

So what if he doesn’t fit into an easily recognizable box of daydream boyfriend material? He’s contradictory, and contradiction is interesting. Dons a gas mask, but isn’t an edgelord. Blandly dressed, but ridiculously charming. Unreadable and modestly intimidating — until he opens his mouth. Even without the benefit of traversing his route, there’s already so much good stuff to work with, and sure as hell, you’re kept guessing all the way to the end.

Character Development — from reckless devotion into complaisant subservience, complaisant subservience into mutual understanding. And then, of course: free will, and true love.

At its core, DMMD is about a dude with magic mind-melding powers and his merry band of attractive men with — surprise! — crippling emotional baggage. Each route follows the same pattern, simply remixing the individual character interactions and the pace of the program: Aoba finds himself isolated with the love interest, faces various communication issues varying on the scale of frustrating to downright dangerous, wanders into a sketchy section of Platinum Jail, bonds with the love interest over shared duress, breaks into the Oval Tower, faces mental assault by the big bad — and finally, finally, destroys those internal demons plaguing the love interest, releasing the couple onto the path of a real heart-to-heart conversation. And then, you know, the lovey-dovey stuff.

Here’s the thing: as far as romantic progression goes, it’s really not a bad structure. There’s room to bump heads, but also to bond. The Scrap scene is a thematically cohesive and clever way to squeeze in the full breadth of character backstory while simultaneously advancing the plot. In this part, Aoba must become the hero to each of his love interests and save them from themselves. Having become privy to each other’s deepest thoughts and reaching a mutual understanding of each other, their feelings afterwards slide much more naturally into romantic territory. They break free of Oval Tower, make their way home, and have hot, emotionally fulfilling sex or otherwise some variation on the last few steps. The end.

That is, except for Clear.

Clear’s route is refreshing in that he needs none of these things — the climax of his emotional arc actually comes a little after the halfway point of his route. When Clear’s true origins are revealed, he comes entirely clean to Aoba, fighting against his fear of rejection but also trusting that Aoba will listen. It’s a quiet, vulnerable moment, rather than the action-packed tension we normally experience during a Scrap scene.

That doesn’t mean it’s prematurely written in — it simply means that he reaches his potential faster than the other characters. Because of that, he’s free to pursue the next level of his route’s development much, much sooner in the timeline: he overcomes his fears of his appearance, he confesses his love to Aoba, he leaves the confines of a largely dubious master-servant relationship and allows himself to be Aoba’s equal. Clear’s sprite art mirrors his emotional transformation all the way through, exposing him to the literal bone — and Aoba’s affection for him doesn’t change a single bit. Beautiful.

The whammy of incredible moments doesn’t just stop there, though. I don’t exactly recall the order the routes DMMD is ideally meant to be played in, but I believe Clear’s is meant to be last. And if you do, I can guarantee that it becomes a hugely delightful gameplay experience — in order to achieve his good ending, you must do absolutely nothing with Scrap. It doesn’t just subvert our player expectations of proactively clicking and interacting with our love interests; it grabs the story by its thematic reins and yanks it all back to the forefront of our scene.

In every route besides Clear’s, Scrap is a tool used to insert Aoba’s influence into and interfere with his target’s mind. Using his powers of destruction, Aoba is able to prune whatever maligned thoughts are harming his target; in any conventional situation, using Scrap is the right choice.

But one of the central problems in Clear’s route is his conflict between the impulses of his conditioning and his desire to live freely as a human would. Breaking free of Toue’s programming is what initially made him unique; growing beyond the rules imposed by his grandfather is what makes him human. In the final conflict scene, Clear’s decision to destroy his key-lock is an action of true autonomy, made with perfect understanding of the consequences and a sincere, selflessly selfish desire to protect someone he loves. In order to receive his good end, you have to respect his decision. It doesn’t matter which option you pick — by using Scrap, Aoba turns his back on every positive choice he made with Clear and attempts to exert his authority over him. This is Aoba becoming Toue; this is Aoba trying to reinstate himself as ‘Master’ right as he approved Clear as his equal. That’s blatant hypocrisy, and it doesn’t matter if Aoba is trying to do it for Clear’s ‘own good’ — that’s not Aoba’s call to make. If you truly wish to respect Clear’s free will, you will stand by. This is the truth of the moment: Clear has no emotional blockages that Aoba needs to fix. Believe in him, just as he believed in you.

The path to his heart is, and always has been, clear. Scrap was never needed from the start.

While Aoba might be the main character, Clear is undeniably a hero in his own route just as much. Tirelessly earnest and always curious, he leaps headlong into the unknown and emerges with his newfound enlightenment. He’s unafraid of weathering trials, even to the point of accepting death, and returns anew from oblivion to a sweet, cathartic ending. That’s about as textbook hero’s journey as it gets — if that doesn’t make him unquestionably, certifiably, unconditionally human, then I will scream.

And only finally… there is the free end. The final CG is like a throwback to our first impression of him: indistinct, purposefully obscured from proper view. But this time, we know better — and so does Aoba. Looks were never what mattered in Clear’s route. If you were patient, and you were open-minded, and you listened… well, what we realize now is that Clear was doing the exact same thing for you, too.

From a carefree, aimless robot-man with only the gimmick of “eccentric ditz” to carry him forward, we get a supremely more interesting character by the end: a man who has graduated from the well-intentioned but claustrophobic conditioning of his childhood; a weapon who has defied the imperatives placed on him by his creator’s programming; a wanderer who has, through unconditional patience and empathy, discovered love, and striven to become a better person for it. Who was it that ever doubted Clear’s character? He’s the goddamn goodest boy that ever wanted to be a real boy. Of course Clear is human. And in fact, he does it better than every single one of the actually human love interests. You can’t change my mind.

The Romance — kindness is really fucking attractive, okay.

Like I’ve said earlier, I have my Big Fan Blinds stuck on pretty tight. I might be conjuring sparks from thin air. But I think every choice was a deliberate creative decision on the writers’ part, and they deserve all the kudos for it — I’m just the lucky player who gets to enjoy it. But aside from Noiz (who I also think is a perfect darling as well — I could go on and on about him), Clear’s route is a model example for consent and healthy relationships in VN storytelling. This is reciprocated on both sides: never does Aoba infringe on Clear’s boundaries, and neither does Clear. They’re sensitive to each other’s needs and concerns; they ask for permission and stop when it isn’t granted (and when it is, boy do they get frisky — I’m not complaining!) I don’t need to say much more, because I think that consent is both fantastic and yes, incredibly hot (the scene in DMMD is tons more sad, go play Re:connect!). Good writing shows off the massive erotic potential enthusiastic consent puts into intimacy, and Aoba’s and Clear’s relationship is honestly a dream playground. The point is, I think Aoba and Clear genuinely do find equal balance in their relationship by the end of his route (and certainly through Re:connect). If you follow through Re:connect’s storyline, there’s even more thematic richness that comes through in the form of Clear’s greatest asset: communication. The couple get to discuss the long-term implications of them being together; they both offer concerns, points, and assurances to the other, and it’s just a soft, honest moment not so unlike the worries of a real relationship. Hearing is kind of Clear’s motif sense, but it’s really great to see that Aoba also subtly picks it up, really flexes his own communication skills to better engage with Clear.

Point is, Clear’s route spoke to me on a lot of little levels. Design-wise, he’s already got a ton going for him, and his story builds upon it rather than against it, enriching his development and grounding him a little more solidly in the DMMD universe (and in my heart). His route, aside from being emotionally ruinous, carries a pretty solid chunk of world-building (only beaten out by Mink’s and Ren’s, probably), and the romance feels organic, healthy, and realistic. He’s not the only one with an excellent route, but he’s my favorite. If you read through all of this, you’re a real trooper and I’m extremely impressed. Thanks for tuning in. Peace.

#dramatical murder#dmmd#aoba seragaki#clear#dmmd clear#long ass emotional screeching#lOL I FORGOT TO DRAW IN THE UMBRELLA HANDLE ahA#fixed

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Truth Will Set You Free

Tim: We’re in the endgame now. With issue #43, the final plot dominoes fall into place and The Wicked + The Divine takes a major step towards its conclusion. But what do these last revelations mean, and how do they fit in with the thematic arcs the series has established. Thoughts, with accompanying spoilers, follow…

Issue #43 pulls off another subversion of our assumptions, a narrative trick that has almost become one of Kieron Gillen’s signature moves. At the end of the last arc, a question hovered over Laura – if she was no longer a god, what was she? The answer, of course, is that she never was a god, and nor were any of the Pantheon.

While I wouldn’t put it past Gillen to try and fit one last twist in, I think the remaining two issues will focus on emotional resolution, rather than plotting. Working on that assumption, we can probably accept that the series of flashbacks in the middle of the issue are the unvarnished truth. Some elements of what we’ve always been told seem to be true; there are 12 special individuals born every 90 years. But that’s about the limit of it.

They are not gods. They do not need to be awoken by Ananke. There is no need for them to die within two years.

Godhood is nothing but a story that these individuals have been convinced to live within. It provides them with access to greater power – Ananke calls it a “shortcut” – but it comes at a price. If you believe the story, and live as if it is true, it burns you out.

That initial bargain we were told about is still accurate – enormous power in return for a lifespan of two years – but there is nothing divine about it. The Pantheon are not reincarnated gods, they have simply been sold the same story as previous iterations. The names may change, but Ananke works from the same archetypes, and taps into common themes and weaknesses in order to convince the new generation that they are divine.

At the end of the day, it works on the same principles as every classic con-artist trick: it’s easy to convince people of a lie if they want it to be true. Every member of the ‘Pantheon’ wanted to be special, and along comes Ananke with a very convincing story telling them that they are. If I lived in the world of WicDiv, I’m sure I’d fall for it too.

Now that the mechanic behind the Pantheon’s power has been made clear, we can dig into what it means. Back when WicDiv was first announced, Gillen called it “a superhero comic for anyone who loves Bowie as much as Batman”. The revelation that our cast of characters have powers even without their ‘godhood’ certainly begs a comparison to things like Marvel’s mutants and Inhumans or DC’s metahuman population, a similarity that wasn’t there before. But in other, more crucial ways, WicDiv inverts the traditional pattern of superhero comics and turns metatext into text.

When writers are developing superheroic characters, they will often work from existing archetypes, ones that have developed over time as the genre has evolved. The classic hero. The dark antihero. The relatable teenager. The fish-out-of-water. The cunning rogue. While not every hero fits neatly into a simple trope, it’s worth noting that many of the more successful ones do, having been purposefully constructed to fill a role, adapted over time to work better or – for particularly successful characters – having built a new archetype around themselves that is then imitated.

This process is sometimes even acknowledged in the text – when working on the Justice League in the late 90s, Grant Morrison deliberately styled them as a ‘modern pantheon’, with Superman as a sun god, Batman as a nocturnal underworld figure, etc. However, WicDiv goes one step further and actually pulls this process into the fictional world of the book. It is only when they embrace an archetype that the characters gain their greater power. They draw their strength and ability from the cultural heft of their iconography, and lose that ‘divinity’ when they acknowledge that they are less (and more) than a symbol.

We can take this inversion even further when we consider Watchmen and other stories that examine the impact of superpowers on the human psyche. In these types of story, it’s frequently the case that having access to extraordinary power leads to characters becoming distant and detached from humanity. In WicDiv, that very act of detaching, of considering yourself apart, is what leads to the power.

It’s a theme that Gillen and McKelvie have included in their work before. In the second and third volumes of Phonogram Emily Aster details how, in order to gain power and cast off the misery of her adolescence, she had to create a new identity, one that was simpler and more archetypal. By becoming less of a person, she becomes a stronger Phonomancer. Unlike the characters in WicDiv (Ananke aside), she makes this choice knowingly and willingly – a sacrifice in return for power and success.

Of course, even though we’re quoting one of its creators, describing WicDiv purely as a commentary upon superhero comics is selling it short, and the metaphor of Ananke’s trick has more than one interpretation. WicDiv is also about art, performance and creation, and we’ve written numerous times before about how those themes relate to the identities that the Pantheon choose to inhabit. Persephone mentions that the alternative to embracing the story and ‘godhood’ is “a lifetime of work to learn what you can”, and as a metaphor for the cult of celebrity and artists buying into their own self-mythologising, it certainly works.

Every member of the Pantheon has pretended to be something they aren’t, or taken on a role they feel obligated to fill. Their divinity is just another variation of that, a story about themselves they chose to believe. Rather than simply a person who can do something that others can’t, they have separated themselves off as a different class, a higher being worthy of worship. Even Tara, who strained against her ‘divinity’, still believed she belonged up on a stage, believed that she had something that set her apart.

Go back to the very first issue of WicDiv – Laura wasn’t content to simply be in the crowd. She had to craft her own godly identity, marking herself as separate from the rest of the audience and as a peer to the ‘divine’ Amaterasu.

If we apply this lens to the world of pop music, then Ananke becomes the predatory agent, producer or record company, convincing those with talent that they are a star, molding them to fit a simpler, more marketable role. She pampers the ego of her charges, and has them compete with each other so they do not band together against her. Of course, this path leads to self-destruction, and when the talent is exhausted and gone, only Ananke remains, having secured everything she needs to carry on and search out the next wave of talent.

This final twist in the nature of the Pantheon brings together almost all of the themes that The Wicked + The Divine has examined over its run. It’s a beautifully elegant bow on the narrative, synthesising the ideas of identity, performance, humility, power, youth and more. It re-asserts the humanity of the characters over everything else, declaring that they are not just simple symbols, but complex and contradictory people.

There’s a Terry Pratchett quote about how most immoral actions can be boiled down to treating people like they aren’t people. Convincing people that they aren’t people is an even crueler trick, and seeing our cast break free from that thinking is immensely satisfying.

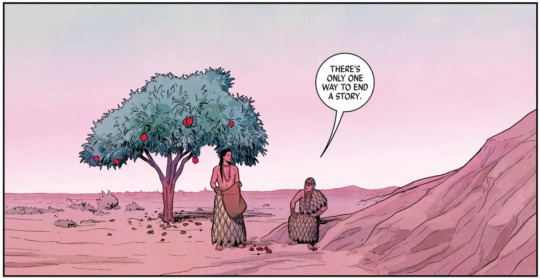

In issue #39, Persephone states that there’s only one way to end a story, and #43 shows it isn’t with death, or new life, or victory. It’s by deciding not to tell it anymore.

Like what we do, and want to help us make more of it? Visit patreon.com/timplusalex and pledge to gain access to exclusive blogs, ebooks, mixtapes and more.

58 notes

·

View notes