#Robinson gets a hard time in reviews for his portrayal‚ but he had a tough job; he was a last minute re cast after prev Quatermass Reginald

Text

REVIEW: Ang Huling El Bimbo The Musical

TRIGGER WARNING. This should be watched with caution as it contains graphic violence. Spoilers also ahead, so skip if you haven't seen it yet.

It started with a cassette tape being played, which may state that the plot is a creative take solely on the song title. Most Filipinos grew up listening to Eraserheads, both young and old. We have our own stories to be reminded of whenever we hear any of their tracks. I think this notion played a major part to lure the people to see the play. It simply screams nostalgia, with a promise of another tale to take away.

Three friends from college presently pursuing successful but separate lives were brought together to be questioned by the police due to the death of a girl who’re once very close to them. The unfortunate event forces them to deal with their haunting past that they have been putting on hold for years and trying to escape from. The characters and scenes will be represented along with the songs from Eraserheads.

Emman: “Both of you tama na! Wala na kong pakialam kung ano man ‘yang bagahe niyo [o] ano man ‘yang gimik niyo. Ang klaro sakin, kailangan na natin ‘tong gawin: tayong tatlo, sama-sama, for once and for all. Isipin niyo na lang, panahon na. ‘Di ba? Kailangan na.“

Whether things in our life have closure or not, every one of it, every person we know, will affect us one way or another. From here, it was clearly presented that they were running from something, but the details of it was yet to unfold. Slowly, we were brought back to university life of these men. We are treated with short scenes that may or may not have happened to us from that era of our lives, when everything sounds hopeful. All opportunities seemed close and within reach, hence the symbolism of them raising up their hands toward heavens, toward their dreams.

Hector: “Alam mo, tsong, ngayong nandito ka na, lahat magbabago: pananaw mo, kilos mo, pati punto mo.”

Anthony: “Oo nga! Kasi alam mo, Emman, for the first time, we are finally and totally free. Ayan na oh.”

Emman: “Kahit saan ka pumunta, may koneksyon ka pa rin. Sa pamilya mo. Sa bayan mo.”

I particularly love the scene where Anthony (played by Phi Palmos) in the midst of his peers’ blossoming lovelives, remained positive and said, “Eh yung crush ko, malapit na kong...pansinin.” After that, his friends joined him in his enthusiasm.

Pare Ko depicts a man in love, in shambles, and in need of advice. It was shown as a group of (mainly) men doing military drills, an emphasis on masculinity of the song. Nothing else speaks men better than being a soldier. When Anthony sang the bridge, for a moment, we are taken to the vulnerable side of being infatuated, something we rarely see with men. We remember that being in love is a beautiful place, no matter how crazy it gets. From their civil military training, through Officer Banlaoi, the three men got to meet and befriend Joy.

One major flaw of hers was she considered every man her savior. This could be the reason why she didn’t take Banlaoi’s forwardness and acts of service as a red flag, and continued to rely on him even at her expense. “Hanap ko lang naman, ‘Tiyang, katapat at katuwang,” she told ‘Tiyang Dely. “’Yon lang naman pangarap ko sa buhay e: ang makahanap ng magiging mabait sakin,” she told Hector, “Di mo maiintindihan ‘yon kasi ang dami niyong pangarap. Ang dami niyong kayang gawin. Nakakapag-aral kayo. May kinabukasan kayo. Kaya niyong abutin ang lahat. E ako?” As we go along, she will attempt to further her dreams, but her low self-esteem stayed with her. Her friendship with the trio may have ushered her to believe more, but that’s the farthest she got. For her, she’ll never be capable of anything. She ended this dialogue with “Ayoko nang umuwi ng probinsya...habang buhay na lang ako aasa,” a foreshadow of her decision to leave ‘Tiyang Dely alone to go back home in the province.

Andre: “Joy, walang ganoon. Walang tinutulungan lang ng ganoon-ganoon. Palaging may kapalit ‘yon.”

Life is never always fancy. When they sang Wag Kang Matakot to each other, it gave us an assurance that even when matters go downhill, there’s no need to afraid. When the going gets tough, we go through it together.

Finally, we get to the graduation. Their getting in and getting out of the university is freedom. Once again, they raise up their hands, reminding themselves of the goals they are now nearer to than they were before. They invite Joy to Antipolo and see the overlooking view, to bid their farewells to her. This should’ve been a good memory. Graduation should’ve been the symbol of their independence. The horrendous events that transpired after incarcerated them forever, still able to achieve but merely surviving, never at peace.

There was a warning at the beginning of the stream but I guess I didn’t pay attention to it, or maybe it didn’t provided the right amount of caution to its viewers. The rape scene got me immobilized to my seat. It was hard for me to re-watch the whole musical to compose a more elaborate review, especially this scene. I’m actually stalling now, repeatedly bringing to mind that they are professional actors and this is fiction. It’s tempting to mute, but it’s going to be unfair to not see the entirety of it. To play Ang Huling El Bimbo here, while being the better verdict is nonetheless unsettling.

Just as perplexing is the graduation ceremony. Everyone is wearing purple instead of the usual black. The color reminded me of death. Joy bringing garlands to them further echoes this, seeing that this similarly depicts a wake. Another beautifully haunting is them singing With A Smile in various rhythms. 'TIyang Dely was sent back home to province due to bankrupt. She thought she’ll be with Joy, but got fooled by her. Joy held on more to Banlaoi as his sole rescuer after being abandoned by her friends.

‘Tiyang Dely: “Kaya nga kung kaya. Anong kapalit?”

How can they leave their friend just like that? They are traumatized, too, but they’re not the ones who got raped. They kept refusing to talk to her even after years have passed and it’s Joy who kept reaching them out. I understand if they’re blaming themselves for what happened. They wanted to ease their guilt, but to be selfish in this situation is unacceptable. It angered me when the adult Anthony said, “There are just some things you don’t want to go back to, and people you don’t need to remember,” as if that was like any other heartbreak to move on about.

Anthony: “Puta, habang buhay nating dadalhin ‘to e.”

Hector: “Kaya ni Joy ‘yan.”

Emman: “Gago, so balewala na lang?”

Hector: “Ako nang bahala. Kakausapin ko si Joy.”

Emman: “Anong magagawa ‘non?”

Hector: “Sasabihin ko sa kanya na kaya niya ‘to.”

Emman: “E gago ka pala talaga e.”

When Banlaoi pointed a gun at her, she gasped with fear, hands shaking. He then told her, “Ingat ka.” This is the only time that he poised to end her life. She was able to tolerate all the abuses and be under this appalling man as long as he keeps her and her family alive. She thought that she’s still in control, but his gesture said otherwise. This puts her into panic and called Emman, Hector, and Anthony one last time. Got caught in the midst of their personal predicaments, they all cut the phone call, saying they have problems of their own too and don’t need more from other people. While the men were struggling to maintain their posh lives, Joy was fighting for her life.

Hector: “Pag tumatawag siya, di ko alam anong isusumbat niya. I mean, you can’t forget these things.”

Contrary to their belief, the reason why she kept bugging them is because she’s trying to tell them that she’s alright. and they need to worry no more. She doesn’t want them to be victims of the past anymore.

‘Tiyang Dely: “Ni minsan, hindi niya kayo sinisi sa nangyari sa kanya.”

After the news of Joy’s death, they all gathered at the morgue. Banlaoi tried to be of help by giving them money, but ‘Tiyang Dely strongly refused, getting Ligaya at her back and out of his sight. What followed was Hector telling her, “Kami na po bahala sa lahat ng gastos,” stupidly missing the hint earlier. This made ‘Tiyang Dely cry (I mean, come on, dude still hasn’t learned his lesson) saying, “Ganoon na lang ano?”

Ligaya, after mourning for her mother’s death, stopped her tears flowing before facing Anthony, Emman, and Hector. She conversed as if she knows them too well, while they don’t know her at all. The three men promised to take care of her. They lay Joy to her final rest along with their grievances of the past. If only they faced the monster under their beds a little bit earlier, they could’ve gotten it out completely. The guilt may now be bearable, but the fact that they could’ve saved not just Ligaya but also Joy is the hard truth they will be carrying for the rest of the lives.

Awful things aside, Ligaya wearing white signifies hope. She is her mother without the burdens of her past. The ending brings back Hector’s car with their young selves reaching out to heavens, reaching out to their dreams. They are joined atop the car with Joy, who’s noticeably not raising her hands. Ligaya is now with them, dancing like her mother once was.

Other things worth mentioning:

Tindahan ni Aling Nena performance, specifically Anthony’s line “shampoo, toothpaste, toothbrush, noodles...yun lang.”

The not-so-subtle rally for free education in the Pare Ko performance.

Yes. Phi Palmos as Anthony. That’s it. Period.

Gab Pangilinan’s portrayal of Joy is superb! Her vocals is breathtaking. From the time she sang Ligaya, I looked forward to her every appearance. Her transformation from being bubbly to troubled soul after one scene is impressive.

Vic Robinson’s (Andrei) and Joy’s mash-up of Ligaya and Tama Na, then ‘Tiyang Dely enters, singing “Ganiyan ma-inlab”.

Wishing Wells as Emman’s love letter to his girlfriend

Menchu Yulo, who played the adult Joy, didn’t exude distress as Gab Pangilinan had done, and made Joy’s struggles less believable.

Some people have expressed disappointment due to its lack of solution on the pressing social issues. In my opinion, I think it wasn't meant to give an answer. Like any work of art, it made a statement. It just happened that what it said was disturbing. However, it is up to us, who lives in the reality of these characters, to do better accordingly.

We should all see AHEBTM in theaters since some parts aren’t focused due to camera work. I hope that once the pandemic ends, they’ll give this musical another chance on stage.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foreigner Himself

Nicholas Ray is a filmmaker who is celebrated as the poet of lonely souls. His films portray people who feel displaced and estranged even on fairly familiar ground. “I’m a stranger here myself,” says a character from what must be the most unique western ever made. All of Ray’s characters are kindred spirits to that one in Johnny Guitar (1954). They are homeless -- in the less urgent meaning of the word. These existentialist themes of solitude and alienation were not uncommon for Ray’s generation of American directors, who had their breakthroughs right before the invasion of television during the late 1940′s and the early 1950′s, but no one tackled them with the cinematically energetic sense of existential malaise as Ray did. To the new generation of young French film critics, primarily in the 1951 founded film magazine Cahiers du cinéma, these fresh American directors with their quickly produced B films exemplified novel individuality, stylistic personality, and poignant critiques of the American society. All the young American directors were rising poets to them. But Ray was their darling. Above all, it was Ray who represented the individual who could find a place for his own original expression in the Hollywood studio system. His films of the 50′s, such as In a Lonely Place (1950), On Dangerous Ground (1951), and Rebel without a Cause (1955), were fierce, distinctive, poetic, and full of cinematic energy. Classical virtues of coherence were secondary to the young Turks of Cahiers; to them, a film with even a few shots of personality could win over a classically good film of quality that had no personality to it -- that lacked what some of them called poetic intuition. Ray was the embodiment of such cinematic poetry. To Jean-Luc Godard, as he famously wrote in a review of Ray’s Bitter Victory (1957), Ray’s name was simply synonymous with the seventh art.

Like his peers -- as well as other Hollywood directors -- Ray eventually succumbed to the big studio system, as that seemingly eternal giant was taking its last breaths, by making big-budget spectacles at the end of his career. After his fairly successful Biblical epic King of Kings (1961), Ray made another historical spectacle for producer Samuel Bronston. Unlike its predecessor, however, 55 Days at Peking (1963) bombed at the box office and had a negative critical reception. While many of the generic films of this transitional era -- such as Ben Hur (1959), Spartacus (1960), and Cleopatra (1963) -- were not very good in any artistic sense, they usually made a lot of money. The financial and artistic disappointment of 55 Days at Peking must thus have been even more tragic for Ray as the film that practically ended his career [1]. In a strange way, nevertheless, it feels like a very appropriate end for Ray’s time in Hollywood’s limelight of outsiders.

A Ray Story

55 Days at Peking takes its title from Noel Gerson’s novel of the same name which concerns the actual 55-day-long Siege of the International Legations, a climactic event during the Boxer Rebellion in China, which The Sun called “the most exciting episode ever known to civilization” [2]. The Boxers were Chinese nationalists who opposed foreign forces in China. Christianity represented such foreign presence at its most salient. The Boxers performed martial arts in the streets and started to gain big support after famine and anti-imperialist sentiments had begun to spread in the country in the late 19th century, partly due to a humiliating loss in a war to Japan in 1895. The Boxers’ violent attacks on foreigners and Chinese Christians reached a peak in the summer of 1900 when they forced some of them into a siege for 55 days. On August 14th, the siege ended in the foreign victory of the Eight-Nation Alliance (consisting of countries that were to tear each other apart in the following two world wars!). A year or so later, the Boxer Rebellion came to an end. It was the loss of the Boxers in the Siege of the International Legations, however, that had sown the seeds for the downfall of the Qing Dynasty, which fatally took the side of the Boxers in the conflict and was finished itself a decade later as China became a republic in 1912.

The fact that the historic event has been pompously called “the most exciting episode ever known to civilization” should have already sparked the interest of more than a couple Hollywood producers (there’s a tagline ready to be printed), but it has surprisingly been filmed very rarely on screen. And for some reason this catchphrase did not catch the attention of the film’s advertisers -- which strikes me as odd for the simple reason that back then they used anything as a selling tagline. Reasons are probably plentiful, but what is more interesting in this context is that the story of the Boxer Rebellion from an Anglo-American perspective sounds perfect for a director like Ray. Although 55 Days at Peking represents Ray’s artistic downfall, which was less than just metaphoric as he collapsed during production due to his declining health, it does exemplify the main themes of Ray’s cinema -- or Ray as cinema -- and Ray finding his own place somewhere else. Rather than picking up the many problems in the film, which I will bring up later, I would like to linger on appreciating this suitability of the story for Ray that is not all unambiguous and, as far as I know, has rarely been recognized by people writing on the film. What I wish to point out is that even though the genre (historical spectacle) and the subject matter (the Boxer Rebellion or, more generally, Chinese history) are foreign to Ray’s cinema, the core of the story (an American individual feeling not-at-home) and some of the film’s stylistic aspects ring true to what we could call, in the spirit of the young French critics, Ray’s poetic intuition.

55 Days at Peking centers around an American major, Matt Lewis (played by the biggest star of the Hollywood historical spectacle, Charlton Heston), who knows the local ways of Beijing. He is introduced to us as the leader of the US military garrison filled with young blood to whom he tells that they should not think any less of the Chinese just because the Chinese do not speak English -- and proceeds to arrogantly teach them the only Chinese words they’ll need, “yes” and “no,” because everything is for bargain and nothing is free. Arriving at his hotel, Lewis meets what will turn into his love interest, a Russian Baronness Natasha Ivanoff (played by Ava Gardner), who seems like an abandoned character from a Tolstoy novel. She wants to leave China but cannot because her visa has been revoked by the brother of her late husband who, as it is later revealed, committed suicide due to Natasha’s extra-marital affair with a Chinese officer. The dire situation in Beijing turns worse when the Chinese Empress of the Qinq dynasty decides to take the side of the Boxers in the heated political climate. As the siege begins, Natasha and Lewis find themselves trapped in a foreign country. Lewis gets help from a British officer, Sir Arthur Robinson (played by David Niven) with whom he blows up a Chinese ammunition warehouse. In the final act of the film, Lewis needs to leave Beijing to deliver a message to nearby Allied forces in order to put an end to the siege. While he is gone, Natasha sells a valuable necklace of hers, which would provide an ace against her brother-in-law, to acquire food and medical supplies for the wounded westerners and Chinese Christians. Her material sacrifice is elevated by a spiritual one since she dies in the process of providing help to those who need it. Lewis’ message reaches the Allied troops, but he will not be reunited with his love. Shortly after his return, the Allied troops arrive and put an end to the siege.

Cut Loose

Despite the many shortcomings of the film, which I will dissect in a moment, the heart of this story is Lewis’ experience -- which also ties it to Ray’s cinema. Granted, it is hard to see this if one looks at 55 Days at Peking as an individual film or in the context of other Hollywood spectacles from the late 50′s and the early 60′s. Viewed in the context of Ray’s oeuvre, however, 55 Days at Peking looks less like a failed portrayal of the Boxer Rebellion and more like a big (if not entirely successful) tale of alienation. Thus, from an auteurist perspective, the film opens up as a story about Lewis’ sense of homelessness in a foreign environment that is growing more hostile toward him.

All of Ray’s films depict individuals who are tormented by a sense of homelessness. They of course experience it even in their domestic environments. The famous line cited above from Johnny Guitar is the most well-known example. The title of In a Lonely Place says it all as it is a portrayal of people in Hollywood. The theme is also articulated quite concretely in Ray’s films that involve characters moving to another place, though still within America. In On Dangerous Ground, a tough cop must move elsewhere to find home. In Rebel without a Cause, a teenager’s loss of direction is aggravated by his family moving to a new town. As far as I know, 55 Days at Peking is Ray’s only film in which the central character resides in a country other than the States. Lewis’ sense of homelessness, innate to him as a character in the Ray universe, is only heightened by such displacement. Making matters worse for his implicit malaise, which remains unaddressed at the level of the film’s dialogue, one might say, the social atmosphere starts boiling up. It is during the hottest months of the Boxer Rebellion that the sweats of his homelessness come to the surface. And this is essentially what happens to Ray’s characters in his other films as well, though in a less grandiose scheme.

55 Days at Peking begins with a sequence in the Forbidden City where an execution of a Chinese general is about to happen because the general, part of the Chinese army, has been shooting the Boxers. One of the leading figures in the army, Jung-Lu arrives to call off the execution. He asks the Empress to take his life instead of the general’s because it was he who gave the command to shoot the Boxers. “They were burning Christian missions, killing foreigners,” Jung-Lu pleads in an effort to justify his command. The Empress declines his offer, listening rather to an ancient prediction in a fatal mistake of taking the side of the Boxers. As a smug smile raises on the Empress’ face, the sequence concludes with a brief and surprising low-angle shot of the executioner swinging his sword from the top frame to the low frame, implying the off-screen cut of the Chinese general’s neck. As the sword falls to the low frame of the shot, however, there is -- in a stroke of visual genius -- a cut to a medium close-up of Heston as Lewis. A clever way to end the first sequence and tie it in with the next, this transition is the best cut in the whole film. More than an energetic beginning for what turns out to be a mediocre story, the cut also has a thematic dimension.

In order to appreciate all of this, let us take a moment to remind ourselves that Ray is often celebrated as one of the great visionaries of the CinemaScope format. Already his Rebel without a Cause brought new sensitivity and intimacy to the newly invented (in 1953) wide aspect ratio that enhances horizontal compositions in a way that is usually just for “snakes and funerals,” as Fritz Lang cunningly puts it in Godard’s Contempt (1963, Le mépris). The width of ratio tends to encourage directors to cut less and use larger shot scales, but Ray combines the wide aspect ratio with close-ups and a faster editing rhythm in Rebel without a Cause -- which is, in my view, alongside Max Ophüls’ Lola Montès (1955), the best CinemaScope film. The introduction of Heston as Lewis in 55 Days at Peking bears resemblances to this. The shot of the executioner swinging his sword is extremely brief (barely a second), but it lies in between of two shots that are longer in duration: the medium close-up of the Empress indulging in her fatal decision is four seconds, the medium close-up of Lewis is seven seconds. The brief shot in between creates an abrupt, surprising sense of acceleration in the film’s editing rhythm, which is calmer in the rest of the film. It makes the visual transition from the Empress to Lewis feel quick, abrupt, out of the blue. Such editing is not considered the done thing when it comes to the use of the CinemaScope aspect ratio. Nor is the use of close-ups. But Ray creates a language of his own out of all of this. It’s a minor detail, you might say, but it’s really one of those small wonderful things that remind you that you are indeed watching a Hollywood spectacle by a real auteur rather than an anonymous factory. I think the cut is definitely worthy of more attention.

The cut from the Empress to the executioner or the cut from the executioner to Lewis is not a match cut; yet it is a match cut of sorts. A match cut in the traditional sense is a cut between two shots that share a visual correspondence: a similar object lies within the same area in their distinct screen spaces (the most famous example being the match cut from the extinguishing match to a setting sun in Lawrence of Arabia, 1962, another CinemaScope spectacle from the same time). While the shot of the executioner lacks direct visual correspondence with either the shot that precedes it (the medium close-up of the Empress) or the shot that follows it (the medium close-up of Lewis), there is not just a match between the two medium close-ups separated by the shot of the executioner but there is also a less visual and a more mental equivalence between the shots due to the cutting.

The equivalence comes from the idea of cutting. The executioner is a character who cuts necks and hence his position in the brief shot that mediates two longer shots is a clever idea in itself. The movement of his sword serves as a ticking clock for the shot’s duration. Thus it wires a tension and creates a visual conflict, which will turn into a dramatic one in the film, between the Empress (or the Qing dynasty in general) and Lewis (or the foreigners in general). The cut is also associated with the political act that already happens now in the Empress’ decision to continue with the execution even though she will make this decision more explicitly later in the film: to take the side of the Boxers. It is the act of cutting ties to the foreigners. After all, the execution takes place because Chinese generals have been shooting the Boxers who have been killing foreigners. This is the main thematic function of this cut. When put in words, it might start to sound too much on-the-nose. But when seen in the film, it is implicit and subtle.

There is yet another function, however, though it is a far subtler one. The shot of Lewis is in the scale of medium close-up (from the clavicle upward), but since Lewis’ head is moving vertically within the confines of the frame (horizontally his head stays put due to the synchronized movement of the tracking camera), the shot also has this strange framing where Lewis’ head lies in the very lowest area of the screen space, the rest of his body cropped off (including his neck and clavicle), with some superfluous empty space above and around his head. The cut to the next shot, a long shot of Lewis with his military garrison, introducing him like a character from a Fordian cavalry western, affirms that this movement is due to horse-riding, but taken in isolation, there is this strange visual movement of the head in space. Granted, the spectator does not experience the movement of the dislocated head as strange because they are used to associate such movement as well as the character’s attire with riding a horse (a call-back to cavalry westerns). However, since the brief shot in between has created this sense of not only acceleration but also haste, the shot of a head in space does catch one a bit off guard. It is the first shot of one of the film’s main characters after the 14-minute opening sequence. It is crucial that this shot in particular introduces the protagonist of the film. It’s a very Ray-esque shot: a lone man being nowhere. The sense of visual strangeness, visual unheimlich, if you will, in the shot is later heightened by the fact that the spectator learns that Lewis is indeed a resident in a foreign country where he does not belong. This obviously plays a part already in creating this initial visual strangeness because we are transformed, via the cut, from the Forbidden City of Beijing to a lone man straight from a cavalry western in anonymous space. There are Chinese buildings in the background, but their cultural architecture is hardly recognizable. They are just buildings that are in contrast to Lewis’ clothing and being, his whole habitus. He is homeless, cut away, floating in air. He is, to paraphrase Johnny Guitar, a stranger here himself -- even though he teaches crude lessons to his soldiers about China.

The theme of home is thus articulated visually before it grows out from the narrative. On the narrative level, the theme is treated by Lewis’ relationships to the other characters, primarily to two female characters.

One of the chief dramatic motifs for the theme of Lewis’ alienation (or his sense of unheimlich, not-being-at-home) is a young Chinese-American girl. She is the daughter of one of Lewis’ soldiers who has had a love affair with a Chinese woman, but the woman has been killed. In the beginning, the soldier asks Lewis for advice with regard to the girl: should he take her back home to the United States or leave her in China as an orphan? Lewis replies cynically that the girl should definitely be left in China because back home she would be “treated like a freak,” while here “she’ll be among her own kind.” Putting aside the character’s racism for a moment (after all, the girl is also half-American), Lewis’ cynicism, I believe, exemplifies his attitude toward himself more than toward anyone else. He himself feels like a freak, a creature hanging in mid-air, cut loose from the homestead. When the girl’s father dies in action during the siege, Lewis must confront his cynicism or self-loathe as he has to inform the girl of her father’s passing. After a series of attempted evasions of duty, Lewis goes to the Christian mission to talk with the girl. He manages to imply the truth, but is unable to say it up front. He asks help from the Christian minister there who tells him that all men are fathers to all children, but one can believe this only if one feels that way about the world. On a wider scale, the minister is speaking for a non-cynical attitude toward the world. After the siege has ended, Arthur (the Niven character) tells Lewis that now he will leave China and go live “every Englishman’s dream” with a family, a few books, and a dog in the countryside. Nothing less cynical than that. He then inquires about Lewis’ future plans.

Arthur: “What about you? What’s home to you?”

Lewis (laughing): “I don’t know... I have to make one yet.”

In the final scene, as he is once again riding on a horse, going away from his non-home, he picks up the young Chinese-American girl from the crowd. Although his change of heart is motivated by the character’s arc throughout the narrative, there is a similar feeling of haste to this decision as there is to the abrupt cut in the beginning. There is optimism in the end, but also, within the context of Ray’s whole oeuvre, the film’s ending seems too good to be true.

Another important element for Lewis’ character development and the theme of home is his relationship with Baronness Natasha Ivanoff (the Gardner character). It is quite appropriate that Lewis lays eyes on Natasha for the first time while his soldier is telling him about the young Chinese-American girl. He meets her at the hotel where they play a game of sexual innuendo. Soon, a more emotional connection starts to build between them. In the scene where Natasha reveals her past to Lewis (that her husband committed suicide because she was unfaithful to him with a Chinese general), she asks him, connecting their relationship to the young Chinese-American girl, whether the same could not have happened to him: “Couldn’t you have fallen in love with a Chinese girl?” Lewis has no answer, but he kisses Natasha fiercely. It’s an affirmative answer that is obstructed by his cynicism or self-loathe. Although the fact that nobody in this film speaks anything but English might be disorienting, it is true that Natasha is a foreigner not just in China but to Lewis (the American-as-can-be Heston) as well. She’s Russian -- which meant two different things in 1900 and 1963 (and yet again in 2020). Natasha has her own character arc of growing away from selfishness to altruistic self-sacrifice. Thus she further motivates Lewis’ development. In her death, Lewis experiences a loss of love and becomes more aware of his tormenting homelessness, which, in the end, makes her pick up the young Chinese-American girl. Whether it is his new-found altruism or his egoistic fear of loneliness that makes him do this is arguable. Similar ambiguity lies in the emerging sense of responsibility at the end of Rebel without a Cause as a fellow young man’s death shakes something up in the torn-apart protagonist.

A Triumph (of sorts) in Weakness

Unfortunately, it’s precisely these two major sub-plots (Lewis’ relationships to the young Chinese-American girl and the Russian woman, Natasha) that are the biggest weaknesses of the film. This is unfortunate because, when it comes to narration, these are the main aspects in which Ray deals with the leading theme of homelessness in the film. It is true, of course, that the character of Arthur (played by Niven) is also important: he represents the happy home life that Lewis lacks, while Natasha and the young Chinese-American girl represent possibilities of acquiring it. But the slightly better quality of his character does not excuse the lowbrow characterizations of the two female characters.

First, the young Chinese-American girl is a mere stock character -- less from a Dickensian story and more from mediocre melodrama. Her character is reduced to a sentimental tear-jerker. What makes this worse is not just the film’s duration, which would definitely allow deeper characterization for her, but also its implicit racism that is evident in its reliance on white Hollywood actors playing the Chinese in “yellow face.” While far from the outrageous in-your-face racism of Mickey Rooney’s performance in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), this convention of playing Asian characters in “yellow face” just heightens the superficiality of the Chinese characters. It’s also worth pointing out the confusion that stems from this convention. At times, it takes time to realize that a character is indeed supposed to be a Chinese character. When everybody speaks English and looks like someone from London or Los Angeles, it’s hard to tell. All I know is that Jung-Lu (played by Leo Genn) definitely does not look like a Beijing local. Although the young Chinese-American girl does not generate such immediate difficulties in recognition, this background makes the character’s superficiality feel more poignant. She’s nothing but a visual figure -- with a few terribly written lines. On the other hand, there is an argument to be made that she has no other purpose for the film’s narrative -- which is, of course, precisely the problem for some. In this sense, she’s like Natalie Wood’s character in Ford’s The Searchers (1956) who the film’s protagonist, played by John Wayne, first despises but then suddenly embraces. Wood’s character is certainly not a very complex one, but she never feels like a mere tear-jerker either, whereas the young Chinese-American girl definitely does. And that’s essentially the problem here. Since 55 Days at Peking, seen from an auteurist perspective, should not be received as a story of the Boxer Rebellion but as part of Ray’s cinematic oeuvre of tortured and alienated American men, it is less problematic (at least in my opinion) when characters serve only narrative functions for those lonely souls. What remains problematic, when it comes to the aesthetic quality of the film, however, is the childish sentimentality with which the character is constructed.

Something similar goes for Natasha. Gardner is a good actor, but here she is at her weakest. It’s almost like Heston brought out the worst in her. For they were destined to fumble around a decade later in the ludicrously bad disaster film Earthquake (1974). While there is sexual tension between the two from the first scene that introduces them, as Natasha first makes fun of Lewis’ attempts of picking her up but then agrees to share the room with him, it’s a little difficult to buy the love that grows between them quite rapidly. There is a dance sequence -- that must forever exist in the shadows of Visconti’s The Leopard (1963, Il gattopardo) from the same year -- but the love still feels unearned, nevertheless. The scene where the two finally kiss, after Natasha has shared her history of infidelity with Lewis, comes particularly out of nowhere. Making matters worse, the scene ends really abruptly. The kiss has this long set-up with Natasha’s brother-in-law and the lingering disclosure of truth, but then the scene suddenly ends with a quick kiss that transports us to a completely different scene. There is no mediator, just a straight cut. It feels like someone just had to shorten the film and took out the remaining 10-20 seconds of the scene in the last minutes before the film’s release. “Okay, they kissed, let’s move on!” Strangely enough, Natasha is involved in the film’s other terrible cut: a quick pan that turns into a cut when the camera shifts from Arthur mourning his son’s serious injury to Natasha taking care of a wounded man. Let alone the fact that quick pans are not considered the done thing with CinemaScope (and for good reason), it’s quite astonishing how badly this stylistic device fits with the rest of the film with regard to camera movement and rhythm in general. There is no other shot like it in the film. And its distinctive singularity is not of the good kind. There is no raison d’être for it.

Despite these awkward characterizations and stylistic details, there is a sense of Ray’s artistic presence in this film. Ray is known as a director who sometimes did not oversee his projects to the finish line, and, given the fact that he had to stop working due to a collapse on set during production, it is hard to tell which aspects of 55 Days at Peking really come from him. At the very least, however, one can say that the theme of homelessness that is first articulated by cinematic means in the form of a match cut of sorts and then by narrative techniques (albeit poorly executed ones) fits with the rest of Ray’s oeuvre. Even if the narrative techniques with the young Chinese-American girl and Natasha lacked quality, there is something earnest in the portrayal of Lewis’ relationships to them. After all, the point of the film is not to tell this great love story between an American and a Russian nor a story where a lone man grows into a father figure for an orphan. The Russian woman and the Chinese-American girl are there just to bring about something in the protagonist who is the film’s focus. Through them, the film articulates Lewis’ sense of homelessness. In this sense, the unearned love between Lewis and Natasha feels less like a poor version of a great love story and more like an apt portrayal of feelings that are motivated by the characters’ self-loathe and disappointments. Perhaps it’s the kind of infatuation that one wishes to be love even when it is not. It’s the wish-fulfillment fantasy where reality is romanticized -- ideas of love pasted on sore wounds. This can be seen in the scene where Lewis and Natasha meet for the last time. Natasha must cut their meeting short because the doctor needs her medical assistance. Lewis waits in the corner as she does her duty. She comes back and they share this brief impassioned moment. In this scene, Ray’s sense of mise-en-scène is as good as it gets in this film. The quicker cutting separates the two, and the strong contrasts of shadows in the space exhale a sense of death above them. We know that this will not last -- and we seem to share the characters’ implicit epiphany that maybe it even should not. When Arthur expresses his condolences to Lewis’ loss, Lewis’ indifferent shrug is simultaneously repressive and honest.

It’s this aspect of idealized love in a reality that lacks it and alienation in a hostile environment that make 55 Days at Peking an interesting film. At its heart, it is a story about abandoned alienated people trying in vain to find each other, which casts a shadow of doubt above the happy ending. These aspects also make it a Ray film. Its cinematic energy, evident in the match cut of sorts, comes from the poetic place of Hollywood that made the young French critics of the 50′s fall in love with the dream factory. While one senses the presence of such fire, one also senses powers constantly putting it down. There’s this strange co-existence of different ideas and forces pulling to the opposite directions in the film. Although 55 Days at Peking is, I believe, best appreciated from an auteurist perspective as a tale of alienation (as a story about Lewis’ experience of homelessness in a foreign environment) and not as a historical story about the Boxer Rebellion, it has two scenes, one in the beginning and one in the end, which try to make it precisely into something like that. During the opening sequence, before the one in the Forbidden City, the camera on a crane descends before two elderly Chinese men. One complains about the noise surrounding them: “What is this terrible noise?” The other responds: “Different nations saying the same thing at the same time, ‘We want China!’” The scene is cheesy, but, more importantly, unnecessary and unfitting for the whole of the film. In the final sequence, there is a similarly awkward brief scene of the Empress repeating the words “the dynasty is finished” in the Forbidden City. The Boxer Rebellion provides a great historical background for Ray’s story about alienation, but the film has really nothing to say about that historical event -- nor should it. In these two scenes, however, the film seems to think not only that it should have something to say about it but also, and more embarrassingly, that it actually does have something to say about it. These two scenes perfectly exemplify the film’s confusion over its own identity which might, in fact, be the most appropriate (albeit tragic) way to end Ray’s career in Hollywood where he was constantly trying to find his own voice, his own sense of home, surrounded by forces that felt foreign to him.

Notes:

[1] Although Ray still made two films afterwards, We Can’t Go Home Again (1973) and Lightning Over Water (1980), his poor health did not allow him to be responsible for them as the primary director. He made We Can’t Go Home Again with his students and Lightning Over Water is more a film by Wim Wenders than it is by Ray. At the very least, 55 Days at Peking is Ray’s last film made in Hollywood -- in the world that made him who he is as an artist.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_the_International_Legations

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

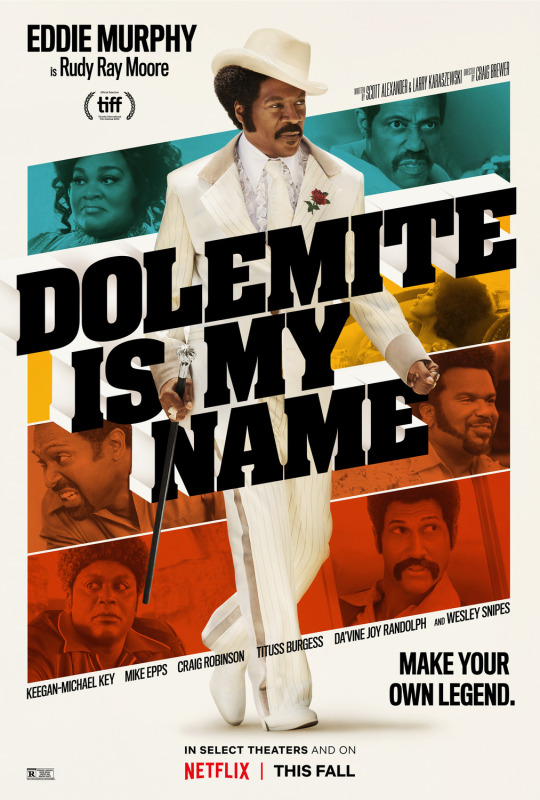

Review : Dolemite Is My Name (2019)

Netflix is doing any and everything that they can in order to legitimize themselves as a viable source for original entertainment, and 2019 has been the year where they’ve made some of the biggest moves to date. Rolling into the summer, a slate of announcements were made about projects tied to major motion picture stars and directors, and one of the first to make noise involved the possible career resurrection of Eddie Murphy. This project turned out to be the wildly popular biopic Dolemite Is My Name.

Rudy Ray Moore (Eddie Murphy) is a down and out performer trying to make an impression in 1970s Los Angeles, but he is finding it hard to be taken seriously in an industry that seems dead-set on leaving him behind. After local bum Ricco (Ron Cephas Jones) invades his record store looking for a handout, Moore is struck with inspiration by Ricco’s soliloquies. The inspiration leads to Moore transforming his nightclub act into his comedic persona, the soon to be world famous Dolemite, a raw pimp with a penchant for storytelling and a natural gift of gab. The fame of his improved nightclub act creates a demand for recorded material, which raises his name and value to new heights. After seeing an uninspired film, Dolemite realizes he can spread the shine of his star further and wider with via the medium of film. With the help of screenwriter Jerry Jones (Keegan-Michael Key), director/actor D’Urville Martin (Wesley Snipes), and young cinematographer Nicholas Josef von Sternberg (Kodi Smit-McPhee), Dolemite and crew set out to make his vision a reality. After a rough, bare-bones production finalized by Martin’s abandonment of the project, Moore sets out with Dolemite in hand, with hopes of fame and success to follow.

Setting up Rudy Ray Moore as a phoenix risen from the ashes of failure is a unique presentation for the iconic character that the world has come to know as Dolemite. Like a modern day street philosopher, he put pieces of real life together and laid it out in a way that people could not help but respond to... in turn, he became a champion for those who had yet to be championed. His grassroots, independent spirit and nature became the blueprint for many DIY artists, including an entire generation of hip-hop artists that became icons in their own right. Moore had an uncanny knack for pure entertainment due to his familiarity with vaudeville and the chitlin’ circuit, so it came to no surprise that he was able to transplant his success into various mediums, specifically live performance, records and film.

The film does a good job of showing how Rudy Ray Moore drew inspiration from his tough times, and the way he was observant enough to notice how people reacted to the rawness of the street without letting the street defeat him. The dedicated way he catered towards those who influenced him without selling out to the mainstream (read : white) audiences is also portrayed successfully via the paralleled success of his contemporaries that do this very thing, to varying degrees. The moral issues that arose from his comedy being promoted as pornography create unique tension among those who supported Moore, due to their connections to the ‘smut’ he produced and the controversy it created.

Craig Brewer uses a pretty straightforward approach to film-making due to the fact that the personalities on screen are so large and dynamic. The costuming matches the range of personality, with both the casual and the standout outfits utilizing great color combinations. The music is extremely strong as well, be it the soundtrack, the original songs created for the film, or the sparse uses of score. Plenty of humor is found at a deeper examination of Rudy Ray Moore’s creative process, especially during the filming sequences, where his acting and kung-fu shortcomings took on a charm of their own.

Eddie Murphy is given a perfect platform to display his dynamic communicative range, both on an individual and a performer level, with his humor and emotional range on full display... though nowhere near as raw around the edges as Rudy Ray Moore, his performance still works. Wesley Snipes gets to work a thin line between a seasoned actor with an ego and a struggling actor realizing his opportunities are running thin. Keegan-Michael Key continues to find roles that keep him out of standard trope territory, allowing him to keep an air of dignity to his performances. Da’Vine Joy Randolph plays sage and ingenue to Murphy’s portrayal of Moore, dispensing advice and support to help push things forward. Mike Epps, Craig Robinson and Tituss Burgess help keep things light and funny with their quick wit and observational humor. Kodi Smith-McPhee’s fish out of water placement works well in the blue world of Dolemite. The massive cast is rounded out with appearances by Aleksandar Filimonovic, Tip Harris, Ron Cephas Jones, Luenell, Gerald Downey and Bob Odenkirk, plus cameos by Snoop Dogg, Chris Rock, Tommie Earl Jenkins and more.

My Name Is Dolemite is definitely a major step in the right direction for Netflix in regards to solidifying their goal as a legitimate avenue for filmmakers. The film stands up on its own merit, and with the cast attached, this film easily could have made a decently successful run, but having the instant access to it that Netflix provides makes the enjoyment that much better.

#ChiefDoomsday#DOOMonFILM#CraigBrewer#DolemiteIsMyName#EddieMurphy#DaVineJoyRandolph#KeeganMichaelKey#MikeEpps#CraigRobinson#TitussBurgess#WesleySnipes#AleksandarFilimonovic#TipHarris#ChrisRock#RonCephasJones#Luenell#GeraldDowney#JoshuaWeinstein#AllenRueckert#KodiSmitMcPhee#TommieEarlJenkins#SnoopDogg#BobOdenkirk#BarryShabakaHenley#TashaSmith#JillSavel

0 notes