Text

Philosophy as Therapy: Living the Examined Life

Kevin O’Higgins S.J.

Recent interest in ‘applied’ and ‘practical’ philosophy’ indicates that many philosophers are rediscovering the therapeutic aspect of their discipline.[1] The Greek term therapeía denotes healing. It is appropriate to speak of a rediscovery of the curative powers of philosophy, because even a slight acquaintance with classical authors provides ample evidence of their practical intent. Reading Plato’s Dialogues, for example, we observe a master therapist at work; Socrates understands that thinking well and living well are inseparable. He relentlessly forces his interlocutors to clarify their ideas and question the principles underlying their everyday behaviour.

Socrates set a goodly part of the philosophical agenda with his proclamation that unexamined lives are not worth living. If we don’t know ourselves, anything else we may claim to know will be, at best, a mixed blessing and, at worst, a mortal hazard. The ancient Greeks realised, for example, that simple know-how can prove extremely dangerous in the absence of practical wisdom; technology can provide us with a multitude of means, but their use needs to be guided by a clear view of the end we wish to achieve. The Greeks also emphasised the difference between cleverness and wisdom: the clever person may know how to achieve all kinds of goals, but only the wise person knows which goals are worth the effort.

Aristotle emphasised the close bond between what he terms the intellectual and moral virtues. Insufficient or erroneous information will usually lead to mistaken conclusions. Actions based on such mistakes will, in turn, result in the wrong type of behaviour. Sound knowledge is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for behaving correctly. The Greeks understood that intelligence and goodness are not always found in the same person. Many of history’s most evil monsters were highly intelligent and understood only too well the nature and consequences of their deeds. Intellectual rectitude must be accompanied by a disposition to seek the good of oneself and others. Aristotle regarded the careful formation of such a disposition as crucial.

In his Ethics, Aristotle centres his discussion of the right way to live around the notion of happiness. Being happy is, essentially, a matter of functioning effectively at the highest possible level. He is thinking, of course, of the kind of happiness most appropriate for human beings. Every kind of being can experience a sense of wellbeing and flourishing in accordance with the possibilities afforded by its own nature. Human beings need to experience fulfilment on the biological and sensitive levels, but their happiness cannot be complete unless it includes also the intellectual satisfaction demanded by reason. This, says Aristotle, is not only the type of happiness most necessary for true human flourishing, but also the most constant and enduring.

Dare to think!

Towards the end of the 18th century, Immanuel Kant summed up the spirit of the Enlightenment in the motto “Dare to think!”. He believed that the inability, or refusal, to think for ourselves is the greatest obstacle to humanity’s emergence from childhood into maturity. For Kant, maturity is essentially a matter of becoming self-legislative. Only rational beings can freely choose to live in accordance with rational laws, since the source of such laws is the very same rational faculty that they discover within themselves. Enlightenment thinkers envisaged a new era in which the inner dictates of reason would eventually replace all forms of external authority. In a rationally ordered world, all tension between the individual and the State would gradually dissolve, since each would be mirrored in the other. This utopian vision continues to inspire modern secular societies. However, it becomes very problematic if the props of external authority are debunked without being replaced by the necessary internal resource of rational maturity.[2]

Kant’s concern was echoed in Heidegger’s contention that we had forgotten how to think because we no longer knew what we ought to think about. In common with other early 20th century philosophers, Heidegger was appalled by the manner in which the advance of technology had resulted in an artificial narrowing of our intellectual horizon. His magnum opus, Being and Time, is basically an effort to relocate contemporary human life within the limitless context in which it can only begin to understand itself. The human being is a iectum, thrown into existence without any say in the matter. But, because our nature is to be out there, beyond ourselves, we can transform our existence into a pro-iectum, a striving towards the out-there that never ceases to extend itself beyond our grasp. The principle limitation that we experience in this process is the relentless passage of Time. Even as we strive to construct and transform ourselves and our world, we are aware that our inevitable fate is death. This, in a nutshell, is the great drama of human existence. Our best efforts would appear to be futile and ultimately self-defeating. However, it is the drama itself that makes our existence worthwhile. Without it, nothing would be either meaningful or valuable; we would simply remain thrown into existence, going nowhere and not even aware of our lack of goals. Philosophical therapy tries to help people to dare to think about Being!

Wittgenstein suggested that the goal of philosophical therapy is to rid the mind of linguistically induced confusion. He believed that the solution to most problems consists in demonstrating that there was never really any problem in the first place. Life is neither a problem nor a non-problem, but simply a fact. However, the manner in which we think and speak about it can make it seem very problematical indeed. The philosopher’s task amounts to unravelling the tangles and knots in our thinking and speaking. Wittgenstein agrees with Heidegger that the really important issues in life have to do with meaning and value, but the more language tries to clarify such issues, the more it tends to obscure them. Wittgensteinian therapy tries to clear away the linguistic rubble in order to free the mind to understand that, ultimately, the meaning and value of our existence are not factual problems to be resolved by either science or philosophy. They are, rather, what he terms ‘the mystical’.

What does it mean to be human?

A philosophical approach to counselling maintains the inseparability of the behavioural and cognitive dimensions of human living. Philosophy also insists that the ‘good life’ can only be understood against the much broader canvas of questions concerning the nature of human beings and, ultimately, of reality in general. If we are engaged in the quest for happiness, it seems obvious that we must answer some basic questions concerning the nature of human life. We may well attain a degree of happiness on some levels, but if other important dimensions of our lives are neglected, the overall result may not be very satisfactory. Aristotle understood, for example, that satisfying our material needs alone is unlikely to produce happiness if other, more specifically human, needs are neglected. Hence, confronting the practical issue of how to attain happiness immediately points to the need for a philosophical anthropology.

Are we purely material beings? Is mind reducible to brain activity? Does any part of us survive the death of the body? The answers to these and a host of other questions will have an obvious bearing on how we ought to live in order to attain happiness. A therapist of any description who lacks a philosophy of the human being is like a traveller without a sense of direction. Unless we have some idea of a final destination we have no basis for choosing the best route. Depending on how we understand ourselves, the formula for the ‘good life’ may vary enormously. Should I advise myself or others to ‘eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die’? Or does it make more sense to abstain from worldly pleasure for the sake of attaining a more important, but less tangible, goal?

What does it mean to be?

Ultimately, the problem of human happiness must be understood within a metaphysical framework. This is, perhaps, the level of questioning on which philosophical therapy really comes into its own and distinguishes itself from other forms of cognitive and behavioural analysis. What we can say about human beings, or any type of being, will remain severely stunted and deficient unless we address the ultimate metaphysical issue of the nature of Being as such. Any solution that omits this ultimate dimension can only be partial.

Many non-philosophical therapies are open to metaphysical concerns, but for philosophy they are the primary focus. The metaphysical framework marks the difference between an all-embracing approach to the quest for happiness and mere technique for coping with day-to-day life within the artificially determined and largely unquestioned parameters of ‘life-in-society’ or ‘life-in-the world’. As Sartre and others have pointed out, simple be-ing is much more fundamental than being in any particular situation or context. The simple fact of existing, a fact not of our own choosing, determines the most basic and dramatic characteristics of our individual and collective adventure. This adventure may be made more agreeable or disagreeable by the realisation that, although we had no say whatsoever in our original coming-into-being, much of what becomes of us after that depends on our own choices. Some people are excited by the need to accept responsibility for their own life-choices. Others are terrified by the same prospect.

The kind of beings we are, coupled with the fact that Being appears to offer us an infinity of possibilities, produces a unique form of anxiety, an existential un-ease, that can easily result in an existential dis-ease. The specifically philosophical quest for happiness or the ‘good life’ is primarily concerned with re-establishing a sense of ease at this basic level. It does not deny the need to address more immediate issues related to our being-in-society – family relations, social conditions, etc. – but it recognises and insists that such issues are neither exhaustive nor fundamental. Furthermore, it challenges other therapeutic approaches to question the value of helping people to function within the often dysfunctional context of ‘life-in-the-world’.

In recent times, philosophy may appear to have retreated from the practical problems of day-to-day living and taken refuge in abstract meanderings of little interest to the world at large. To the extent that this is so, it is an aberration rather than philosophy’s normal practice. One has only to consider the extent to which our modern social, political and economic contexts have been shaped by philosophical ideas in order to confirm that this is so. Both liberal capitalist democracy and its socialist alternatives have their origins in 18th and 19th century philosophy. Sometimes, there is nothing so practical as theory.

The applied philosophy ‘movement’ began in Germany about twenty years ago. Since then, it has spread continuously throughout Europe and North America. In some countries, philosophy graduates can seek accreditation from professional associations in order to set up practice as trained philosophical counsellors.

The problems presented by clients vary enormously. A person recently diagnosed with a life-threatening illness may wish to address suddenly urgent issues related to mortality and death. For another person, the motivation may be less obviously related to life-and-death issues; they may simply desire to initiate an open-ended search in the hope of articulating their own personal philosophy of life. Rather than provide ready-made answers, the philosopher’s role is to draw on the extraordinarily rich, 2,500 years old tradition of philosophical reflection in order to indicate pathways that may merit further exploration.

[1] See, for example: Alex Howard, Philosophy for Counselling and Psychotherapy: Pythagoras to Postmodernism (London: Macmillan Press, 2000); Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995); A.C. Grayling, The Meaning of Things: Applying Philosophy to Life (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2001); Lou Marinoff, Plato, not Prozac!: Applying Philosophy to Everyday Problems (New York: Harper Collins, 1999); Alain de Botton, The Consolations of Philosophy (London, Penguin, 2001).

[2] Recent Irish experience of rapid social and cultural change may provide an instance of what can happen when an enlightened minority gleefully sets about demolishing traditional sources of meaning and values without considering the consequences for the unenlightened majority. Is the increase in mental illness and suicide related to the meaning/moral vacuum in which many people are struggling to survive?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Daniel Berrigan S.J. – Priest, Poet, Prophet

Kevin O’Higgins S.J.

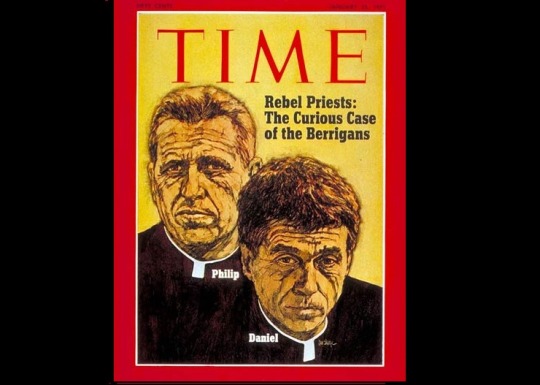

I first became aware of Daniel Berrigan in the late 1960s, when I was in my final years of secondary school. At the time, ‘Dan’ and his brother Philip, together with a like-minded group of friends collectively known as the ‘Catonsville Nine’, were in the news for their non-violent opposition to the war in Vietnam. Their activities included burning U.S. Army draft cards and invading military bases. The Berrigans even adorned the front cover of Time Magazine, which described them as ‘Rebel Priests’. When Dan was sentenced to prison following the Catonsville protest, he decided to symbolically defy the authorities by evading arrest and going ‘on the run’. Consequently, he became the first priest ever to appear on the FBI’s ‘most wanted’ list.

Back then, as a typical hard-to-impress teenager, what really struck me was the fact that I had never encountered Catholic priests like these. I associated priests with altars, pulpits and confession boxes. It came as something of a shock, albeit a pleasant one, to see Catholic priests engaged in anti-war protests and being pursued by the FBI! But Dan, especially, was very emphatic that his anti-war activities were simply an inescapable expression of his Christian commitment and priestly ministry. For me, as for many others, his anti-war, pro-peace ministry was a powerful contemporary affirmation that Christian faith was not just concerned with subscribing to a certain set of beliefs. When he was asked, aged 88, what he was most grateful for in his long life, he replied without hesitation: “My Jesuit vocation”. His only regret was that it had taken him too long to grasp what his Jesuit vocation implied in terms of tirelessly working for peace and defending victims of violence and injustice of all kinds.

Shortly before Dan’s decision to engage in public acts of civil disobedience, the great Fr. Pedro Arrupe had become General of the Jesuits. Arrupe actually visited Dan in prison. Some months later, an Irish diocesan priest happened to encounter Pedro Arrupe while strolling in Rome. In the course of their brief conversation, the priest mentioned that he admired Dan Berrigan. Father Arrupe responded: “Daniel Berrigan is the most faithful Jesuit of his generation!”.

The seeds of faith and concern for justice, planted in the Berrigan home, were nourished and brought to full fruition by Dan’s Jesuit formation, especially through the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. It is not difficult to imagine how his poetic soul would have been moved by the moment in St. Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises when the person praying is asked to imagine the Three Divine Persons observing the state of the world:

... men and women being born and being laid to rest, some getting married and others getting divorced, the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the happy and the sad ... so many undernourished, sick, and dying, so many struggling with life and blind to any meaning.

Many decades before Pope Francis urged members of the clergy to move from the sacristy to the street in order to acquire “the smell of the sheep” and address the needs of ordinary people in the real world, worker priests were pioneering a pastoral approach that saw them exchange elegant clerical garb for factory overalls. Shortly after his ordination as a priest in 1952, Dan Berrigan was sent to France, for a year of Jesuit formation known as ‘tertianship’. While there, he made contact with French ‘worker priests’, and their influence on him proved to be decisive.

In the early 1960s, hunger for change both informed and was given new impetus by the Second Vatican Council. It is not difficult to imagine how Dan Berrigan would have been impacted by a document like the Council’s ‘Gaudium et spes’ and its declaration that: “The joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially of those who are poor or afflicted, are the joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ as well”.

What makes Dan’s long life as a Jesuit, a priest and a committed Christian so exemplary is the fact that his determination to always translate his faith into concrete action never wavered. Right into advanced old age, until frailty and illness obliged him to take a step back from frontline activism, he continued to participate in acts of civil disobedience on behalf of peace. He also continued his involvement with the Catholic Worker movement, founded by his great friend and mentor, Dorothy Day. In his final years, particular concerns of his were people suffering from homelessness and Aids.

In all of his concerns and activities, Dan Berrigan was guided by the specific perspective of Christian faith. This latter point is important. As Pope Francis has frequently pointed out, the Church is not simply a benevolent society or a non-governmental organisation. Observing the world through the eyes of faith is a matter of trying to see it as God does, with all of its light and shadow. Then, it is a matter of striving to ensure that the light triumphs over the darkness. That, in a nutshell, is what is exemplified in the long, extraordinary life of Daniel Berrigan.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Pope Leo XIII in 1896 - oldest known film footage of a pope.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical ‘Rerum novarum’ - 130th anniversary --- Kevin O‘Higgins, S.J.

This year marks the 130th anniversary of Pope Leo XIII’s ground-breaking encyclical, ‘Rerum novarum’, published on May 15, 1891. The title translates as ‘of new things’, and the encyclical itself represented a new way of presenting the Church’s teaching on social matters. It has always been the case that the Church has had plenty to say regarding the practical implications of Christian faith, especially how we ought to treat those most in need of our help. The Gospels make clear that love of God and love of neighbour go hand in hand. Even prior to Christianity, throughout the Old Testament there is a recurring reminder from the prophets that professions of faith in God must be matched by the practice of justice, showing special concern for vulnerable people, such as widows, orphans or strangers in need of hospitality.

19th Century Context

The novel aspect of Rerum novarum is the fact that it takes general principles and values found throughout Scripture and the Church’s Tradition and applies them to a very specific social context. Following the example set by Leo XIII, later pontiffs have similarly issued encyclicals addressing pressing social issues of their own particular time. In the early 1960s, for example, in the aftermath of global war and faced with the threat of nuclear confrontation, Pope St. John XXIII wrote about the need for the peaceful resolution of conflict (‘Pacem in terris’). More recently, heightened awareness of the threat posed by environmental degradation prompted Pope Francis’ encyclical ‘Laudato si’. In every instance, these encyclicals seek to show how perennial truths gleaned from Scripture and Tradition can be brought to bear on contemporary challenges.

By the late 19th century, especially in parts of the world undergoing rapid industrialisation, profound social change was the order of the day. Spectacular advances in science and technology accelerated the demise of the medieval social order. Old certainties and traditional sources of authority were being questioned and discarded. The transition from a predominantly agricultural economy to one based on industry meant, inevitably, that populations tended to concentrate in large urban settings, heralding the steady decline of a traditional rural way of life. By the time Leo XIII writes Rerum novarum, there was already an abundance of commentary on the emerging socio-economic order. Its champions highlighted the extraordinary expansion of industrial production, accompanied by an enormous increase in wealth. Critics like Karl Marx and other socialist commentators decried the concentration of much of the new wealth in the hands of the owners of industry, while workers frequently survived on meagre wages and lived in miserable conditions.

Response to new Challenges

As Pope Leo III surveyed these ‘new things’, he saw the need for a two-fold response. On the one hand, glaring inequities and injustices generated by the emerging ‘capitalist’ socio-economic order were clearly unacceptable from the perspective of Christian morality. Rerum novarum insists on the need to respect the dignity of each and every person, irrespective of the place they happen to occupy in society or the economy. He underlines the essentially social character of human nature. Even 130 years ago, it was possible to discern a tendency to absolutise individual rights and minimise social obligations. This tendency was particularly clear where property rights were concerned. While defending the right to private ownership of property, Leo XIII situates this right within the context of a prior obligation to respect the basic human rights of all members of society, especially workers and their families. The right to possess property or money does not amount to a right to use them without reference to the needs of others. The common good always has priority over the satisfaction of individual desire.

Rejecting False Solutions

The second strand in Leo XIII’s response to the new socio-economic reality is his critique of what he regards as erroneous remedies. More specifically, he rejects suggestions by 19th century socialists that private ownership of property should be entirely abolished. He also warns against those wishing to divide society into hostile classes, since the violent fragmentation of society would end up hurting everyone. Clearly, Leo XIII understands that, left unaddressed, the injustices inherent in unbridled ‘capitalism’ could provoke a revolutionary reaction that would prove even more damaging than the ills it sought to remedy.

Rerum novarum, in common with subsequent papal teaching on social matters, seeks to steer a careful course between the two extremes of atomising individualism and anonymising collectivism. The Church views society as a delicate fabric of relationships, reflecting the essentially social character of human nature. We should be wary of an increasingly intrusive State that seeks to dictate the conduct of all social relations. The State and the economy exist in order to help individuals to flourish. Any tendency to reduce human beings to the status of servants of a State or an economy must be rejected. Between the individual and the State, there are many intermediate levels of association, beginning with the family. The State must respect subsidiarity, avoiding interference in matters that are best addressed at more local levels.

Evolution of Church’s Social Teaching

These and other central themes in Rerum novarum have been developed and refined over the past 130 years, and the process continues. For example, more recent papal encyclicals, informed by advances in the human sciences, show a clearer grasp of the manner in which inequity and injustice become embedded in social structures and institutions. Whereas Rerum novarum may appear to reflect a conservative 19th century view that each individual’s place in society is preordained, nowadays we are more familiar with the notion of social mobility and the need to remove discriminatory barriers to advancement. Increasingly, such insights lead the Church to engage also in self-critique as a precondition of credibility when seeking to teach secular society how to order its house correctly.

1 note

·

View note