#yannis ritsos

Photo

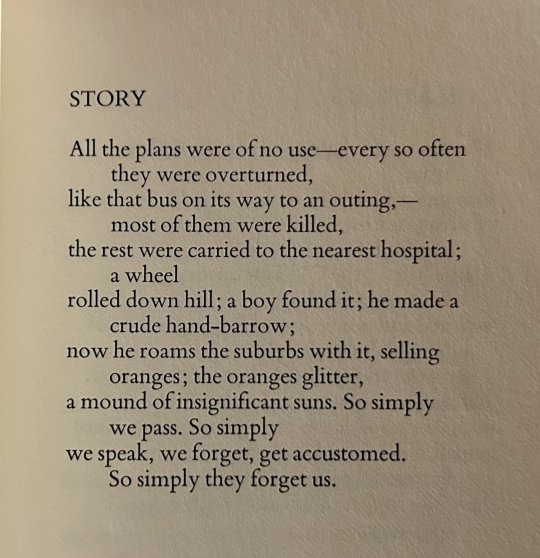

Yannis Ritsos, “The Meaning of Simplicity” (tr. Kimon Friar)

#the way i spent years of my life thinking the first stanza was the entire poem and then.....anyway eternally forever and always#q#lit#quotes#poetry#poems#yannis ritsos#the meaning of simplicity#archive#briefwechsel#m#x

750 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ovunque tu sia io Ti circondo....

Ghiannis Ritsos

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

gençliğimin çiçeği, gecelerimin işkencesi. bir daha görecek miyim seni?

umberto eco - yanlış okumalar

#kitap#edebiyat#blogger#felsefe#kitaplar#blog#kitap kurdu#charles bukowski#şiir#umberto eco#yanlış okumalar#poems#love letters#simone de beauvoir#birhan keskin#sylvia plath#frida kahlo#yannis ritsos#tumblr şiir#şiirsokakta#turgut uyar#vladimir nabokov#tan kızıllığı#friedrich nietzsche#genç werther'in acıları#goethe#ilyada#odysseus#the odyssey#homeros

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orestes, Yannis Ritsos (The Fourth Dimension)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yannis Ritsos, from the collection “Exile and Return | Selected Poems 1967-1974”, translated from Greek by Edmund Keeley, Anvil Press Poetry, 1989

Privilege

by Yannis Ritsos

This up and down, he says, I don’t understand it.

To forget myself I look into the small mirror;

I see the motionless window, I see the wall -

nothing changes inside or outside the mirror.

I let a flower lie on the chair (for as long as it lasts).

I live here, at this number, on this street.

And suddenly they raise me (the chair and the flower too),

they lower me, raise me – I don’t know. Luckily

I managed to put this mirror in my pocket.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moonlight Sonata

A spring evening. A large room in an old house. A woman of a certain age, dressed in black, is speaking to a young man. They have not turned on the lights. Through both windows the moonlight shines relentlessly. I forgot to mention that the Woman in Black has published two or three interesting volumes of poetry with a religious flavor. So, the Woman in Black is speaking to the Young Man:

Let me come with you. What a moon there is tonight!

The moon is kind—it won’t show

that my hair has turned white. The moon

will turn my hair to gold again. You wouldn’t understand.

Let me come with you.

When there’s a moon the shadows in the house grow larger,

invisible hands draw the curtains,

a ghostly finger writes forgotten words in the dust

on the piano—I don’t want to hear them. Hush.

Let me come with you

a little farther down, as far as the brickyard wall,

to the point where the road turns and the city appears

concrete and airy, whitewashed with moonlight,

so indifferent and insubstantial

so positive, like metaphysics,

that finally you can believe you exist and do not exist,

that you never existed, that time with its destruction never existed.

Let me come with you.

We’ll sit for a little on the low wall, up on the hill,

and as the spring breeze blows around us

perhaps we’ll even imagine that we are flying,

because, often, and now especially, I hear the sound of my own dress

like the sound of two powerful wings opening and closing,

and when you enclose yourself within the sound of that flight

you feel the tight mesh of your throat, your ribs, your flesh,

and thus constricted amid the muscles of the azure air,

amid the strong nerves of the heavens,

it makes no difference whether you go or return

and it makes no difference that my hair has turned white

(that is not my sorrow—my sorrow is

that my heart too does not turn white).

Let me come with you.

I know that each one of us travels to love alone,

alone to faith and to death.

I know it. I’ve tried it. It doesn’t help.

Let me come with you.

This house is haunted, it preys on me—

what I mean is, it has aged a great deal, the nails are working loose,

the portraits drop as though plunging into the void,

the plaster falls without a sound

as the dead man’s hat falls from the peg in the dark hallway

as the worn woolen glove falls from the knee of silence

or as a moonbeam falls on the old, gutted armchair.

Once it too was new—not the photograph that you are staring at so

dubiously—

I mean the armchair, very comfortable, you could sit in it for hours

with your eyes closed and dream whatever came into your head

—a sandy beach, smooth, wet, shining in the moonlight,

shining more than my old patent leather shoes that I send each month to

the shoeshine shop on the corner,

or a fishing boat’s sail that sinks to the bottom rocked by its own

breathing,

a three-cornered sail like a handkerchief folded slantwise in half only

as though it had nothing to shut up or hold fast

no reason to flutter open in farewell. I have always had a passion for

handkerchiefs,

not to keep anything tied in them,

no flower seeds or camomile gathered in the fields at sunset,

nor to tie them with four knots like the caps the workers wear on the

construction site across the street,

nor to dab my eyes—I’ve kept my eyesight good;

I’ve never worn glasses. A harmless idiosyncracy, handkerchiefs.

Now I fold them in quarters, in eighths, in sixteenth

to keep my fingers occupied. And now I remember

that this is how I counted the music when I went to the Odeion

with a blue pinafore and a white collar, with two blond braids

—8, 16, 32, 64—

hand in hand with a small friend of mine, peachy, all light and pink

flowers,

(forgive me such digressions—a bad habit)—32, 64—and my family

rested

great hopes on my musical talent. But I was telling you about the

armchair—

gutted—the rusted springs are showing, the stuffing—

I thought of sending it next door to the furniture shop,

but where’s the time and the money and the inclination—what to fix

first?—

I thought of throwing a sheet over it—I was afraid

of a white sheet in so much moonlight. People sat here

who dreamed great dreams, as you do and I too,

and now they rest under earth untroubled by rain or the moon.

Let me come with you.

We’ll pause for a little at the top of St. Nicholas’ marble steps,

and afterward you’ll descend and I will turn back,

having on my left side the warmth from a casual touch of your jacket

and some squares of light, too, from small neighborhood windows

and this pure white mist from the moon, like a great procession of silver

swans—

and I do not fear this manifestation, for at another time

on many spring evenings I talked with God who appeared to me

clothed in the haze and glory of such a moonlight—

and many young men, more handsome even than you, I sacrificed to

him—

I dissolved, so white, so unapproachable, amid my white flame, in the

whiteness of moonlight,

burnt up by men’s voracious eyes and the tentative rapture of youths,

besieged by splendid bronzed bodies,

strong limbs exercising at the pool, with oars, on the track, at soccer (I

pretended not to see them),

foreheads, lips and throats, knees, fingers and eyes,

chests and arms and thighs (and truly I did not see them)

—you know, sometimes, when you’re entranced, you forget what

entranced you, the entrancement alone is enough—

my God, what star-bright eyes, and I was lifted up to an apotheosis of

disavowed stars

because, besieged thus from without and from within,

no other road was left me save only the way up or the way down.—No,

it is not enough.

Let me come with you.

I know it’s very late. Let me,

because for so many years—days, nights, and crimson noons—I’ve

stayed alone,

unyielding, alone and immaculate,

even in my marriage bed immaculate and alone,

writing glorious verses to lay on the knees of God,

verses that, I assure you, will endure as if chiselled in flawless marble

beyond my life and your life, well beyond. It is not enough.

Let me come with you.

This house can’t bear me anymore.

I cannot endure to bear it on my back.

You must always be careful, be careful,

to hold up the wall with the large buffet

to hold up the buffet with the antique carved table

to hold up the table with the chairs

to hold up the chairs with your hands

to place your shoulder under the hanging beam.

And the piano, like a closed black coffin. You do not dare to open it.

You have to be so careful, so careful, lest they fall, lest you fall. I cannot

bear it.

Let me come with you.

This house, despite all its dead, has no intention of dying.

It insists on living with its dead

on living off its dead

on living off the certainty of its death

and on still keeping house for its dead, the rotting beds and shelves.

Let me come with you.

Here, however quietly I walk through the mist of evening,

whether in slippers or barefoot,

there will be some sound: a pane of glass cracks or a mirror,

some steps are heard—not my own.

Outside, in the street, perhaps these steps are not heard—

repentance, they say, wears wooden shoes—

and if you look into this or that other mirror,

behind the dust and the cracks,

you discern—darker and more fragmented—your face,

your face, which all your life you sought only to keep clean and whole.

The lip of the glass gleams in the moonlight

like a round razor—how can I lift it to my lips?

however much I thirst—how can I lift it—Do you see?

I am already in a mood for similes—this at least is left me,

reassuring me still that my wits are not failing.

Let me come with you.

At times, when evening descends, I have the feeling

that outside the window the bear-keeper is going by with his old heavy

she-bear,

her fur full of burrs and thorns,

stirring dust in the neighborhood street

a desolate cloud of dust that censes the dusk,

and the children have gone home for supper and aren’t allowed

outdoors again,

even though behind the walls they divine the old bear’s passing—

and the tired bear passes in the wisdom of her solitude, not knowing

wherefore and why—

she’s grown heavy, can no longer dance on her hind legs,

can’t wear her lace cap to amuse the children, the idlers, the

importunate,

and all she wants is to lie down on the ground

letting them trample on her belly, playing thus her final game,

showing her dreadful power for resignation,

her indifference to the interest of others, to the rings in her lips, the

compulsion of her teeth,

her indifference to pain and to life

with the sure complicity of death—even a slow death—

her final indifference to death with the continuity and the knowledge of

life

which transcends her enslavement with knowledge and with action.

But who can play this game to the end?

And the bear gets up again and moves on

obedient to her leash, her rings, her teeth,

smiling with torn lips at the pennies the beautiful and unsuspecting

children toss

(beautiful precisely because unsuspecting)

and saying thank you. Because bears that have grown old

can say only one thing: thank you; thank you.

Let me come with you.

This house stifles me. The kitchen especially

is like the depths of the sea. The hanging coffeepots gleam

like round, huge eyes of improbable fish,

the plates undulate slowly like medusas,

seaweed and shells catch in my hair—later I can’t pull them loose—

I can’t get back to the surface—

the tray falls silently from my hands—I sink down

and I see the bubbles from my breath rising, rising

and I try to divert myself watching them

and I wonder what someone would say who happened to be above and

saw these bubbles,

perhaps that someone was drowning or a diver exploring the depths?

And in fact more than a few times I’ve discovered there, in the depths of

drowning,

coral and pearls and treasures of shipwrecked vessels,

unexpected encounters, past, present, and yet to come,

a confirmation almost of eternity,

a certain respite, a certain smile of immortality, as they say,

a happiness, an intoxication, inspiration even,

coral and pearls and sapphires;

only I don’t know how to give them—no, I do give them;

only I don’t know if they can take them—but still, I give them.

Let me come with you.

One moment while I get my jacket.

The way this weather’s so changeable, I must be careful.

It’s damp in the evenings, and doesn’t the moon

seem to you, honestly, as if it intensifies the cold?

Let me button your shirt—how strong your chest is

—how strong the moon—the armchair, I mean—and whenever I lift the

cup from the table

a hole of silence is left underneath. I place my palm over it at once

so as not to see through it—I put the cup back in its place;

and the moon’s a hole in the skull of the world—don’t look through it,

it’s a magnetic force that draws you—don’t look, don’t any of you look,

listen to what I’m telling you—you’ll fall in. This giddiness,

beautiful, ethereal—you will fall in—

the moon’s a marble well,

shadows stir and mute wings, mysterious voices—don’t you hear them?

Deep, deep the fall,

deep, deep the ascent,

the airy statue enmeshed in its open wings,

deep, deep the inexorable benevolence of the silence—

trembling lights on the opposite shore, so that you sway in your own

wave,

the breathing of the ocean. Beautiful, ethereal

this giddiness—be careful, you’ll fall. Don’t look at me,

for me my place is this wavering—this splendid vertigo. And so every

evening

I have a little headache, some dizzy spells.

Often I slip out to the pharmacy across the street for a few aspirin,

but at times I’m too tired and I stay here with my headache

and listen to the hollow sound the pipes make in the walls,

or drink some coffee, and, absentminded as usual,

I forget and make two—who’ll drink the other?

It’s really funny, I leave it on the windowsill to cool

or sometimes I drink them both, looking out the window at the bright

green globe of the pharmacy

that’s like the green light of a silent train coming to take me away

with my handkerchiefs, my run-down shoes, my black purse, my verses,

but no suitcases—what would one do with them?

Let me come with you.

Oh, are you going? Goodnight. No, I won’t come. Goodnight.

I’ll be going myself in a little. Thank you. Because, in the end, I must

get out of this broken-down house.

I must see a bit of the city—no, not the moon—

the city with its calloused hands, the city of daily work,

the city that swears by bread and by its fist,

the city that bears all of us on its back

with our pettiness, sins, and hatreds,

our ambitions, our ignorance and our senility.

I need to hear the great footsteps of the city,

and no longer to hear your footsteps

or God’s, or my own. Goodnight.

The room grows dark. It looks as though a cloud may have covered the moon. All at once, as if someone had turned up the radio in the nearby bar, a very familiar musical phrase can be heard. Then I realize that “The Moonlight Sonata,” just the first movement, has been playing very softly through this entire scene. The Young Man will go down the hill now with an ironic and perhaps sympathetic smile on his finely chiselled lips and with a feeling of release. Just as he reaches St. Nicholas’, before he goes down the marble steps, he will laugh—a loud, uncontrollable laugh. His laughter will not sound at all unseemly beneath the moon. Perhaps the only unseemly thing will be that nothing is unseemly. Soon the Young Man will fall silent, become serious, and say: “The decline of an era.” So, thoroughly calm once more, he will unbutton his shirt again and go on his way. As for the Woman in Black, I don’t know whether she finally did get out of the house. The moon is shining again. And in the corners of the room the shadows intensify with an intolerable regret, almost fury, not so much for the life, as for the useless confession. Can you hear? The radio plays on:

YANNIS RITSOS

The Fourth Dimension. Princeton University Press, 1993. Translated from the Greek by Peter Green and Beverly Bardsley.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yannis Ritsos

Vielleicht, eines Tages

Ich möchte dir diese rosa Wolken in der Nacht zeigen.

Du siehst aber nichts. Es ist Nacht – was kann man da schon sehen?

Jetzt bleibt mir nichts anderes übrig, als mit deinen Augen zu sehen, sagte er,

damit ich nicht allein bin, damit du nicht allein bist. Und tatsächlich

ist da nichts, da drüben, wo ich hinzeige.

Nur die Sterne drängen sich in der Nacht zusammen, müde,

wie Leute, die im Lastwagen von einem Picknick zurückkommen,

enttäuscht, hungrig, niemand singt,

mit verwelkten Wildblumen in den verschwitzten Handflächen.

Aber ich werde darauf bestehen, zu sehen und dir zu zeigen, sagte er,

denn wenn du nichts siehst, wird es so sein, als sähe auch ich nichts –

ich werde wenigstens darauf bestehen, nicht mit deinen Augen zu sehen –

und vielleicht werden wir eines Tages aus unterschiedlichen Richtungen aufeinander treffen.

Titel des griechischen Originals: Ίσως μια μέρα. Ins Deutsche übertragen von Johannes Beilharz (© 2022).

Ursprünglich hier veröffentlicht.

Foto von Nacho Rochon auf Unsplash

#Yannis Ritsos#vielleicht eines tages#Gedicht#Gedichtübersetzung#griechische Literatur#rosa wolken#sehen

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sen bir heykelin duyarsızlığındayken

nasıl başa çıkacağım içindeki yangınla?

Göklere inanırdım eskiden, ama sen, denizlerin

derinliğini gösterdin bana,

ölü kentleri,

unutulmuş ormanları,

boğulmuş gürültüleriyle.

Gök şimdi yaralı bir martı,

süzüldü denize.

Sana kargaşalığın üzerindeki

köprüyü kurmaya çalışan bu el kırıldı.

Bak bana:

ne kadar çıplak ve suçsuz

duruyorum önünde.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

the meaning of simplicity by Yannis Ritsos

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

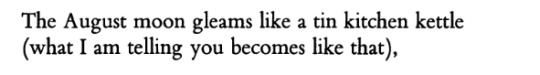

Yannis Ritsos, from “The Meaning of Simplicity” (trans. Rae Dalven)

[Text ID: “The August moon gleams like a tin kitchen kettle

(what I am telling you becomes like that),”]

#q#lit#quotes#poetry#yannis ritsos#the meaning of simplicity#only the moon and i#forever favourite#typography#archive#m#x

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

October 27, 1948 // Yannis Ritsos

There are so many thorns here –

brown thorns, yellow thorns

all along the length of the day, even into sleep.

When the nights jump the barbed wire

they leave tattered strips of skirt behind.

The words we once found beautiful

faded like an old man’s vest in a trunk

like a sunset darkened on the windowpanes.

People here walk with their hands in their pockets

or might gesture as if swatting a fly

that returns again and again to the same place

on the rim of an empty glass or just inside

a spot as indefinite and persistent

as their refusal to acknowledge it.

(translated from the Greek by Karen Emmerich & Edmund Keeley)

#poetry#Yannis Ritsos#Greek poetry#Karen Emmerich#Edmund Keeley#exile#prison#political prisoner#incarceration#despair#barbed wire#fascism#poems of resistance#suffering

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

bir anın, yalnızca bir anın bütün bir hayatı kapladığı anlar… bir an… belki sadece andan ibaret olan bir an. geçirdiğimiz binlerce saniyenin içinden bir şekilde zihnimizin içine sinsice sızmış ve orada bağımsızlığını ilan etmiş bir an.

murathan mungan - yalnız bir opera

#kitap#edebiyat#blogger#felsefe#kitaplar#blog#kitap kurdu#charles bukowski#joachim murat#yalnız bir opera#yaz geçer#vazoda tozlu güller#didem madak#lale müldür#yılmaz güney#ümit yaşar oğuzcan#milan kundera#franz kafka#jorge luis borges#yannis ritsos#konstantin kavafis#cavafy#oscar wilde#orhan pamuk#ahmet altan#beyaz geceler#elif şafak#birhan keskin#sabahattin ali#kürk mantolu madonna

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ şiire, aşka ve ölüme inanıyorum ”

. . .

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orestes, Yannis Ritsos (The Fourth Dimension)

3 notes

·

View notes